Abstract

Background. The salutogenicity of urban environments is significantly affected by their ergonomics, i.e., by the quality of the interactions between citizens and the elements of the built environment. Measuring and modelling urban ergonomics is thus a key issue to provide urban policy makers with planning solutions to increase the well-being, usability and safety of the urban environment. However, this is a difficult task due to the complexity of the interrelations between the urban environment and human activities. The paper contributes to the definition of a generalized model of urban ergonomics and salutogenicity, focusing on walkability, by discussing the relevant parameters from the large and variegated sets proposed in the literature, by discussing the emerging model structure from a data mining process, by considering the background of the relevant functional dependency already established in the literature, and by providing evidence of the solutions’ effectiveness. The methodology is developed for a case study in central Italy, with a focus on the mobility issue, which is a catalyst to generate more salutogenic and sustainable behaviors.

1. Introduction

The quality of urban life depends on the ability to combine the natural environment, the built environment and mobility, so that social and functional needs of the inhabitants are fully satisfied, and the long-term negative impact of health risk factors is minimized. One of the main objectives of the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (GAPPA) 2018–2030 of the World Health Organization (WHO), is to create urban environments that promote and safeguard the rights of all people, of all ages, to have equitable access to safe places and spaces to perform regular physical activity, according to their needs [1,2]. Salutogenicity is a concept that captures in a word this complex statement [3]. The WHO has identified a set of affordable and cost effective interventions to achieve good levels of salutogenicity, providing the greatest possible impact on health by reducing illness, disability and premature death from non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [4]. In particular, increasing all forms of physical activity could provide considerable benefits on different diseases, like type-2 diabetes, dementia, cerebrovascular diseases, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, depression, ischemic heart disease. Jarrett et al. [5] estimates that, in the UK context, a widespread physical activity, such as walking 1.6 km or cycling 3.4 km, would save approximately 17 billion GBP/year in 20 years (1% of the National Health Fund).

By emphasizing the conditioning aspects that the urban structure has on the behaviour of its inhabitants, the WHO objectives establish a direct relationship between salutogenicity and urban ergonomics. In particular, the literature largely supports the WHO perspective, by emphasizing the relevant relations occurring between mobility (i.e., walkable urban environments) and health [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Sallis et al. [14] observe a direct relationship between physical activity and residential density, density of the intersections, density of public transport, number of parks and green spaces within a radius of one km from the house. Similar results have been observed in other studies concerning the relationship between urban spaces and physical activity [15], between the built environment and physical activity [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], and between the built environment and several chronic diseases [24,25,26,27], highlighting some of the main risk factors [28,29,30]. Other consistent evidence concerns the relationship between environmental exposures (e.g., air pollution, noise, etc.), cardiovascular disease and mortality [24,25]. Only few studies, mainly qualitative, correlate the built environment with inhabitants’ perceptions of the outdoor environment (e.g., chromatic and olfactory features) [31]. The wide range of health benefits for all age groups caused by the presence of green elements, which complements the improvement of the ecological–climatic conditions of the cities, is investigated in [32]. In general, the proximity to the parks and recreational environments is associated with reduction in stress, improvement of mental health, stimulated social cohesion, increased physical activity, reduced cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, reduced exposure to air pollution, reduced exposure to excessive noise, and improved comfort [9,33,34,35,36]. However, more studies are required to qualify to a better degree the influences of the size, the distance and of other features of green areas, on the level of physical activity achieved by the population [36]. Even within the transportation and mobility governance domains, the role of walking and cycling is no longer considered just ancillary to motorized modes, with several examples in literature and practice acknowledging physical activity as crucial for sustainable transportation planning [37,38,39]. Moreover, research on innovation for transit facilities strongly relies on ergonomics as an element of strength to increase the attractiveness of public transport and create new urban landmarks [40,41].

Modelling urban ergonomics is a complex issue since it involves a number of different domains, from the citizens’ behaviour to urban planning and building technology. The main problem in modelling systems with a high degree of complexity concerns the achievement of a sufficient level of generality in the representation, so that reliable predictions can be formulated. In the urban ergonomics case, for example, the unsystematic components of citizens’ behaviour, affected by hardly quantifiable socio-cultural aspects, can cause significant variations, from case to case, both in the model’s structure and in the relevance of its parameters. In such situations, a combined probabilistic and case-based reasoning approach can be effective [42]. Case-Based Reasoning (CBR) [43] is a form of exemplar-based analogical reasoning, which provides support to problem solving whenever general domain theories are missing. In CBR, past solutions are reused to solve problems in similar contexts. The practical problem of CBR is that reusing past solutions in new contexts usually requires a portion of general knowledge that is usually not available in the CBR systems. On the other side, probabilistic reasoning, and more specifically Bayesian Networks (BNets), can be used to derive general models that are shared by the elements of a training case set [44]. For example, in transport planning BNets are long used to develop activity-based models, with further applications and case studies on a vast array of fields (from environmental safeguarding, to road safety, to policy decisions, etc.), involving all modes. However, one of the problems arising in using BNets in modelling complex domains is that a general statistic can be hard to achieve because the training set is usually not homogenous within the boundaries of the knowledge modelling set. For example, in urban ergonomics, similar neighbourhoods may have totally different influence degrees of green areas on the general performance parameters. This often happens because the relevant elements fall outside the knowledge boundary of the modelling effort, and, consequently, are not represented. On the other hand, the knowledge modelling effort is always constrained by a number of practical limits, not least, the manageability of the parameter set.

Two main issues emerge at this point of the discussion as the main focus of this paper. The first concerns the identification and qualification of a distinctive set of measurable indicators that reliably captures the influence of the urban ergonomics on the salutogenicity degree of an urban context. The sets of core indicators proposed in the literature [16,29,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54] are scarcely integrated, sometimes unmanageable (i.e., the number of indicators is too high) and sometimes inconsistently shaped (i.e., unbalanced in specific arguments). An in-depth analysis of the indicators proposed in the literature has already been accomplished by the authors [55,56] showing flaws, including data completeness, the difficulty and the cost of accessing the database and the lack of standardization (there is no common standardized method of measurement or cataloguing). Hence, a careful selection of available indicators and their arrangement in a sound, complete and effective set must be developed. The second point concerns the modelling approach. A modelling strategy that is able to overcome the limits of CBR and BNet, by highlighting contextual regularities that would have been otherwise hidden by the domain complexity, must be developed.

The paper structure is as follows. In Section 2, the urban ergonomics indicators that have been used to investigate the salutogenicity of the downtown of the Rieti city, a midsized Italian town close to Rome, are introduced. In Section 3, the paper details the modelling approach and structure of the Bayesian Network model. Analytical results are presented and elaborated in Section 4, and some areas for further improvements are elaborated in Section 5; eventually, concluding remarks are provided in Section 6.

2. The Human–Environment Interface to Link Ergonomics and Sustainability

The urban space’s salutogenicity, as defined above, can be read in terms of ergonomics. More specifically, ergonomics can be defined as: “scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of the interactions among human and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data and methods to design in order to optimize human well-being and overall system performance” [57]. Consistently, ergonomics is multidisciplinary as it focuses on the Human–Environment Interface (HEI) and searches for a concrete and rational answer to such a complex relationship [58,59]. As such, ergonomics is applicable to systems of urban areas. In fact, urban spaces shape the system that structures a city by linking people, places and functions. The vision of the city as a complex system was pioneered by Christopher Alexander in 1965, and epitomized by his statement: “the city is not a tree” [60]. The HEI was central in this approach although, nowadays, a revision placing major emphasis on the sustainability issues is needed. Since the urban environment is, above all, a human environment, the HEI represents the whole set of interactions between the complex systems of urban spaces and the people (or users) who inhabit them and walk within. Quality HEI can be claimed when an urban space’s performance fully meets people’s requirements, starting from Safety and Well-being as primary needs. The meeting of Safety and Well-being requirements implies that the urban environment is designed and structured as a set of spaces where people experience and perceive freedom from whatever sort of risks, danger or losses. In turn, Sustainability can be interpreted as the ability of the users to maintain such status with no (or minimal) long-term negative effects on the environment they experience and perceive. All of the above is complemented by an additional requirement: Usability, i.e., the possibility to perform appropriate functions, complying with Safety and Well-being requirements, within a sustainable approach.

2.1. An Approach to Urban Ergonomics Indicators

Within this vision, ergonomics by managing HEI, can be applied to any phases of planning, design, implementation, evaluation, regeneration, maintenance and improvement of the system of urban areas/spaces, to generate an effective requirement/performance equilibrium. In Italy, the requirement/performance approach was initially developed by UNI (Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione, i.e the national board for standardisation) and applied to standardize a wide range of products, components, services, operations and functions, hence its full transferability to this study, as well.

Measuring or assessing a performance, as the efficiency with which each urban space component fulfils its intended purpose, is the main task within walkability tools. The quality of the performance assessment relies on the accuracy in the investigation and surveys of places, their constitutive elements and the activities they generate. Coherently with the HEI approach, the results from such investigation can be further developed in two ways:

- The conventional walkability exercise: a walkability list is designed to assess a set of performances according to the perception of the urban spaces walked by the exercise participants (surveyors, interviewees); each item in the list is weighted and scored, so as to identify a rank of performance which may enable/hinder people walk the surveyed areas (typically a very specific origin/destination path, e.g., home-to-school) and decide whether they are walkable, and to what extent. To progress beyond this practice, walkability lists can be associated with weighted indicators, for which a range of performance targets are set. Performance targets, in turn, are reported according to threshold and optimal values. Surveyors can score the listed indicators and success can be claimed only when the performance targets are achieved.

- The study of walkability variables: after the detailed survey and the creation of the walkability list, the indicators are interpreted in terms of variables describing the dynamic relationships between the characteristics of the surveyed areas and the behaviour of their inhabitants. The variables can be disassembled and classified in terms of requirement/performance analysis within a BNets process. This gives rise to a structured system of variables classified in terms of needs, requirements and performance.

Each way complements the other, with scientific literature abounding for the former. For the latter, a classification system focused on the Usability, Well-being and Safety requirements, as defined by the UNI standards [61], has been developed and applied to the case study described in Section 4, to highlight the role of each within the ergonomics of urban spaces/areas. More specifically, each Usability, Well-being and Safety need gives rise to several requirements that the urban areas’ performance is designed to meet [62]. The reference for the definition of these needs and the related requirements was based on previous studies [63,64] and synthesized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main needs and requirements within the Human–Environment Interface.

It must be noted that Usability includes the concept of Accessibility, according to its broader definition as the “the ease with which exchange opportunities can be accessed” [65]. Consequently, within HEI, Accessibility is considered as a prerequisite that all the requirements already comply with.

The BNet approach might provide an effective response and a reliable solution to the research question about the complexity in the management of urban phenomena, as it discloses all the interrelations among the HEI components.

According to Table 1, to each need several requirements correspond, and the urban space performance is designed to meet all of them [56].

To quantify the performance levels, a set of 29 measurable performance domains has been defined, according to 5 categories: Natural elements, Built environment, Mobility, Urban furniture and Perceived environment. Each set of performance includes a variable amount of indicators for a total of 67, each of them described according to the measurement unit, threshold and optimal values (with reference to presently existing regulations on this matter), achievable score and weight (Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5). Some of these indicators have been selected from other sets already in use in the literature [56,63,64].

Table 2.

Performance Indicators within the Human–Environment Interface, Natural elements.

Table 3.

Performance Indicators within the Human–Environment Interface, Built environment.

Table 4.

Performance Indicators within the Human–Environment Interface, Mobility.

Table 5.

Performance Indicators within the Human–Environment Interface, Urban furniture and Perceived environment.

Weights for evaluation categories and indicators were developed by a multidisciplinary panel of 10 experts. The preliminary literature review analysis on neighborhood environmental factors affecting walking and, therefore, ergonomics was the basis to define the above-mentioned indicators, evaluation categories and criteria for scores and weights, which were presented to the experts, from different fields: public health, urban planning, transportation and urban policy makers. They were asked to assess the overall set of urban ergonomics indicators and define weights for each indicator. After this first round, the panel of experts, representing the involved fields of study, agreed to participate in a discussion to finalize the weights. The weights reported in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 are the shared result of this discussion [63].

The performance’s value (e.g., A1. Vegetation, etc.) is obtained by adding the scores of the indicators (e.g., A1.1, A1.2, A1.3, etc.), weighted by their relative weight (e.g., wA1.1, wA1.2, wA1.3, etc.), normalized in the interval 0–10, according to the following Equation (1):

where

Pp = [(a*w1) + (b*w2) + (c*w3) + ……..]/10

- Pp = performance score (e.g., A1);

- a,b,c = scores of the individual indicators calculated by the surveyors (e.g., A1.1, A1.2, A1.3);

- w1, w2, w3 = weights attributed to each indicator (e.g., wA1.1, wA1.2, wA1.3).

The Natural elements category in Table 2 includes both man-made components that translate into green public areas, tree lined streets, fountains and waterworks, and the availability of bodies of water, whose effects on the behaviors and habits of the inhabitants are largely recognized in the scientific literature, due to their capacity to mitigate temperature and sun exposure [33,36,66].

The Built environment category (Table 3) relies on indicators applicable to describe the major features of the urban structure, from morphology, to configuration, density, texture and quality and its functions. All highlight crucial features for evaluating the ergonomics of the urban spaces [16,29,63,67,68,69,70,71,72].

In the Mobility category (Table 4), ten indicators specifically describe the infrastructure specifically associated with the capability to increase and facilitate active and sustainable mobility [73,74,75,76,77] as “part of the daily life of all the inhabitants, by means of transportation, free time and workplace activities…” [78]. The Natural elements and Built environment categories describe the urban fabric features where walkability takes place, whereas Mobility assesses the quality of connections to generate walkable conditions. Together, they describe the walkability of the public realm.

The Urban furniture category (Table 5) relies on five indicators to assess comfort and perceived safety. They describe the characteristics of a given urban space needed to increase social interactions and support walking [66,71,79]. To conclude, Perceived environment (Table 5) includes four indicators related to the users’ perception of neatness of the urban space [50,54,73,80]. Both categories represent added values to the walkability of the public realm.

2.1.1. The Performance–Requirement Matrix

The selection of indicators is often a challenging task in planning and evaluation practice. Indicators should be SMART—Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Tangible [81] and, possibly, comparable. Issues of uncertainty and difficulties in the measurements are commonly addressed. For example, accessibility is a broad concept (as synthesized in [82]), measurable in different ways and with different indicators. A control tool is then required to check whether a specific requirement is actually met by a given performance. This could be a control matrix, like the one presented in Table 6, where the requirements from Table 1 are matched with the performance listed in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 6.

The Requirement–Performance Control Matrix.

This control matrix makes it possible to check that each performance of the environment is meeting at least one requirement, from the users’ side. Each single indicator may be used for more than one requirement/performance relationship, which creates a multiscope assessment of the walkability features.

2.2. The Case Study

The set of walkability indicators was tested on a case study where a previous analysis focused on the walkability of the urban areas around the historic center of Rieti, a middle-size province town, 80-km far from Rome, in Central Italy, with just less than 50,000 inhabitants. The former analysis was designed to test and validate a composite indicator, the Walking Suitability Index of the Territory—T-WSI [63]. Unlike other walkability tools, T-WSI was not designed to assess the walking-friendliness of given origin-destination’s paths or trips, but of the whole walking environment of an area, in this case 9 out of 15 neighbourhoods in Rieti. T-WSI can be thus considered the “prequel” of the current HEI approach which, in turn, includes a larger array of indicators (those in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5) and covers a vaster area (approximately 60% of the built area of the city as in Figure 1).

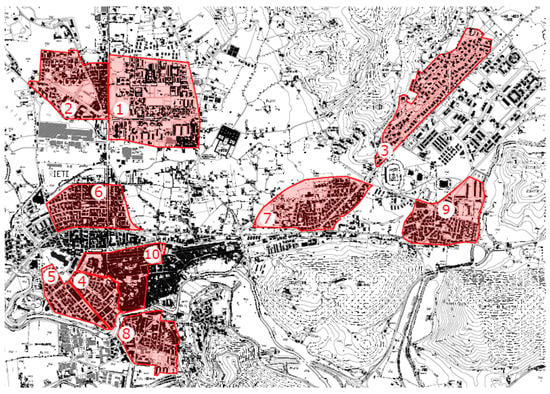

Figure 1.

The case study areas in Rieti, central Italy.

Increasing the number of indicators obviously improves the accuracy of the study and great attention was attached to their SMART characteristics. Within the HEI approach, however, one more advance is represented by the quality of the analysed districts. Areas 1 to 9 in Figure 1 and Table 7 were developed between the 1920s and 1990s, under different planning criteria and visions of the city, but under the same need to provide the 1900s’ expanding population with housing and basic services (schools, churches, etc.). Much different is the city center (Area 10 in Figure 1 and Table 7), which has always been a pedestrian area since it was developed in 1149 as a papal seat. The quality of the built environment is high with narrow alleys, squares and landmarks such as the medieval walls and cultural heritage buildings (with an enforced Limited Traffic Zone—LTZ helping to preserve all of that). Usually, historic centers are not included in the walkability analysis since, by definition, they are fully walkable. In this case, contemplating the city center in the HEI analysis makes it possible to introduce an unusual but significant term of comparison (a reference) among the more modern districts. Moreover, it introduces the research question about the assumed attractiveness of historic areas as a catalyst to attract pedestrians.

Table 7.

Characteristics of the districts in the study area.

To describe the differences between these districts, an abacus of photographs associating local environments with HEI categories is provided in Table 8.

Table 8.

Local environments and HEI.

2.3. The Data Collection

The first step in the analysis was the data collection to “feed” the indicators. A trained researcher was in charge of collecting data for every link of the road network at each considered district. This required surveys, calculations and/or measurements according to the type of indicator to develop. A spreadsheet was specifically designed to collect data for each indicator’s category. Once data were entered, a further data assessment was carried out by a different trained researcher, who performed quality control on a random sample of records, independently re-collecting the same data under the same experimental conditions. Finally, the validated set of entered data was processed and results are presented in Section 3.

3. The Bayesian Network Model

A BNet probabilistic model has been built to seek out and analyse the complex relationships occurring among the different performances, which become “variables” in the BNet model. The BNet model was built in two phases:

- Structural modelling: consisting of the definition of the model structure, which was carried out by determining the conditional independency among the variables;

- Dependency modelling: by calculating of the strength of conditional dependency among the variables.

Both phases were based either on data, through machine learning algorithms (i.e., structural learning and EM-learning), or on first principles implemented by manual coding physical laws, well established rules, or expert knowledge depending on their availability (as further reported). The final model was composed of seven elementary networks arranged in three levels. The first level includes five elementary networks (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6) that represent the basic parameters used to quantify the main features of the urban space ergonomics. Manual coding has been mainly used in first-level networks, since there is a clear functional dependency among the measured parameters and the ergonomic features. Just a small number of inter-parameter dependencies have been derived by data only when a well-grounded explanation could have been formulated.

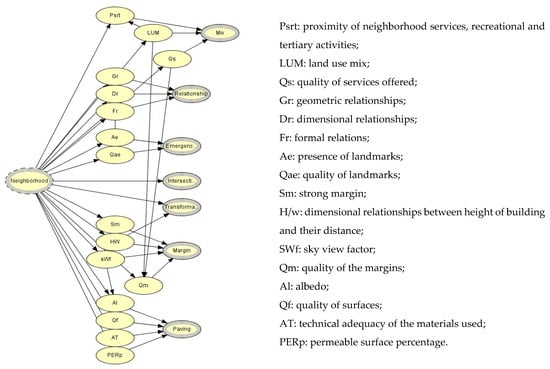

Figure 2.

I level: Bayesian elementary network, Built Environment.

Figure 3.

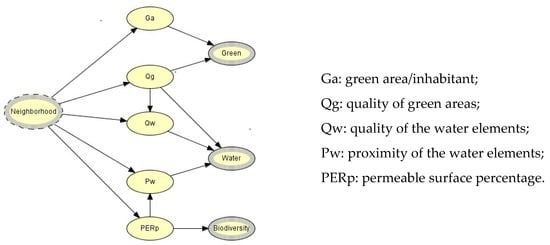

I level: Bayesian elementary network, Natural Elements.

Figure 4.

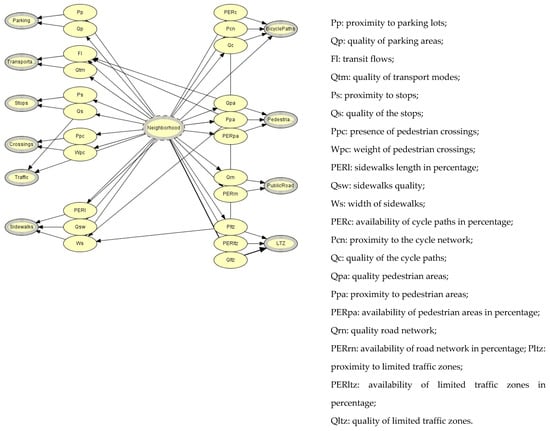

I level: Bayesian elementary network, Mobility.

Figure 5.

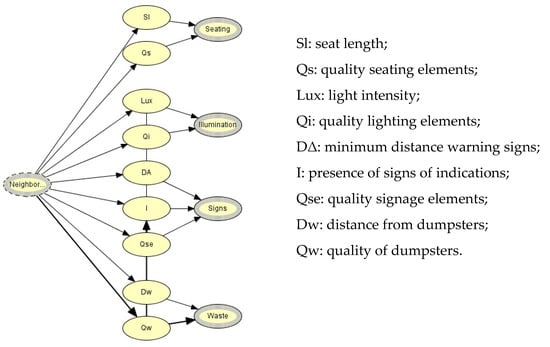

I level: Bayesian elementary network, Urban Furniture.

Figure 6.

I level: Bayesian elementary network—Perceived Environment.

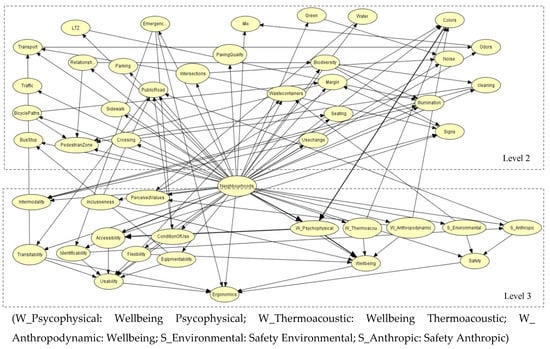

The 29 output variables of these networks are the input nodes of the second level network. The second level is made of a single network (Figure 7—top) that arranges the 29 urban ergonomic indicators calculated by the level 1 networks by establishing the conditional dependencies occurring among them. This network has been derived essentially from data, but a careful and systematic analysis of each derived relation has been carried out, to assess the statistical analysis on a semantic basis.

Figure 7.

The final BNet model representing the ergonomics of urban spaces.

The third level is made of a single network as well, and it is aimed at eliciting and coding experts’ assessment about the performance level of the different neighbourhoods. As for the weights, a group of 10 urban planners and designers, both from professional and academic fields, was involved to assess the quality of the outdoor spaces of each neighbourhood. To this end, the experts have been provided with a specific assessment template where the general performance parameters were detailed (for example, usability is itemized in terms of easiness to equip, transitability, flexibility, accessibility, identifiability and conditions of use). The experts’ assessment outcome has been finally integrated in the overall model using standard BNet learning algorithms. In this way, statistical dependencies have been calculated among the 29 observable neighbourhoods’ ergonomic features and the expert assessments (Figure 7).

Finally, all the variables in the three networks have been connected to the Neighbourhood node, containing just the neighbourhood identifiers, so as to have a case-based reasoning (CBR) support to urban design. By observing or providing evidence to one or more neighbourhood identifiers in the Neighbourhood node, the network shows the statistics of a single case or a combination of cases, respectively. In fact, this inference resembles the case selection in CBR. Through this simple expedient, the network gives the possibilities to compare the models of different neighbourhoods’ cases, pointing out similarities and differences. Furthermore, the neighbourhood identifier can be used as a key to access unstructured information sources (e.g., drawings, photos, tabled data, etc.) stored in complementary data environments, so that the analysis can be easily extended beyond the representation boundary of the statistical model. On the other hand, by selecting a single feature or performance node, the network points out the cases (i.e., the neighbourhoods) that share the selected value and the statistics of the other performance and feature nodes. Hence, by combining observations in the different network levels, a number of interesting inferences can be implemented. In general, the BNet model provides support to preliminary urban design through what-if analysis, by means of forward propagation of the observations of level 1 nodes, as well as support to urban regeneration policies through diagnostic reasoning, by means of backward propagation of observations of level 2 or level 3 nodes. The following section details the networks’ levels.

3.1. Level 1 Networks

Five level 1 networks have been defined according to as many domain analyses: Built Environment, Natural Elements, Mobility, Urban Furniture and Perceived Environment. Direct dependencies among input and output nodes have been manually coded, the output (thick boundary nodes) being weighted sums of the inputs. Occasionally, parallel data analysis showed some strong dependencies between input nodes. These dependencies were included only when they were understood in terms of general theories, hence preserving the highest possible generality degree of the model.

Figure 2 shows the network concerning the Built Environment domain analysis. Data analysis pointed out some dependency relations among features: the sky view factor (sWf) affects the albedo (Al), as it is geometrically explainable, while the quality of the margins (Qm) is affected by the mix of land use (LUM), by the quality of services (Qs) and by the sky view factor (sWf), which can be figured out as well.

Figure 3 describes the network related to the Natural Elements domain analysis of the Water, Green and Biodiversity nodes. Some inter-parameter links occur in this domain as well. The quality of green areas (Qg) affects the quality of the water elements (Qw), and the percentage of permeable surfaces (PERp) affects the proximity of the water elements (Pw). In both cases, this evidence is explicable on a clear conceptual basis, hence, they have been included in the model.

The Mobility domain analysis is represented in Figure 4 where the features of the urban space that enhance sustainable and active mobility are highlighted.

A number of dependencies among urban features, having a plausible ground in theory, have been strongly suggested by the recorded data, and therefore added to this network. These include, the relation between the length of the sidewalks (PERl) and the presence of cycling paths (PERc), the relation between the proximity of the pedestrian areas (Ppa) and the width of sidewalks (Ws), the relation between the proximity of the LTZ (P and the proximity to parking lots (Pp), the relations among the proximity (Ppa) and the quality (Qpa) of the pedestrian areas with the flow of public transport means (Fl).

Figure 5 represents the network of the Urban Furniture domain analysis. Dependency relations among features concern the luminous flux (Lux) and therefore the brightness of an urban space, which influences the quality and affects, therefore, the readability of information signs (Qse). In fact, the quality of these elements is measured by analysing their visibility and maintenance status.

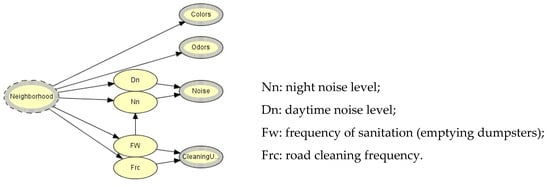

Finally, in the network representing the Perceived Environment domain analysis (Figure 6), the road cleaning (Frc) and emptying waste containers (FW) conceivably influence night noise levels (Nn).

3.2. Level 2 and 3 Networks

Figure 7 shows the final BNet model resulting from the integration of the output nodes of the seven networks (Level 2—top) with the network generated by experts (Level 3—bottom). The relations occurring among nodes at level 2 have been derived from data by selecting the ones that provided strong semantic evidence. In fact, the BNet machine learning algorithms supplied more than one model for the given data set. Among them, the ones that were the most plausible on a semantic basis were selected, excluding ordinary or counterfactual correlations, and correlations that appeared to be scarcely generalizable. The results show the relevant complexity of the real situation, deriving from the high degree of interconnectedness of the urban performance parameters. Each of these links is semantically dense, thus calling for additional multidisciplinary interpretations, to be addressed in forthcoming studies.

The level 3 network captures the general knowledge about urban ergonomics. Our approach, to include directly a significant number of expert assessments, is an attempt to capture and quantify the different perspectives on a statistical basis. The noteworthy point is that level 3 coding has been carried out by experts on a general set of parameters (e.g., intermodality, inclusiveness, accessibility, etc.), which was not directly connected with the performance variables part of level 2.

A final issue concerns the relationships occurring among level 2 and level 3 nodes. In this research, the case-based approach implemented by the Neighborhood node provided an initial solution to the problem, acting in principle as a sort of naïve Bayesian classifier. Then, a number of direct relations have been implemented, as in the previous levels, when the data provided strong insights about semantically well-grounded correlations.

4. Results Analysis

Following the layered model structure, the analysis is arranged by levels. According to the HEI approach, level 1 network analysis provides an overview of the general urban ergonomic indicators for each neighborhood and a quantitative assessment of the indicators’ scores to highlight drivers and barriers for walkability. Level 2 and 3 network analysis provides an integrated and more systemic evaluation of ergonomics according to the emerged Bayesian Network structure.

4.1. General Urban Ergonomic Indicators—Level 1 Network Analysis

The availability of a large test area, which amounts to 10 neighbourhoods, ensures a good soundness of results and the emergence of performance gaps and critical factors affecting walkability in real built environments.

Table 9 shows the scores of each indicator and the average scores per performance obtained in the investigated neighborhoods. The table also shows, for each indicator, the percentage of neighborhoods with unsatisfactory scores and, for each district, the percentage of indicators with unsatisfactory scores. In this preliminary study, the values ≥6/10 have been arbitrarily considered satisfactory.

Table 9.

Scores of each indicator for each neighbourhood in the case study.

The analysis on the neighbourhoods stresses how the city centre is the most walkable, as expected. Likewise, the second and third ranked districts (Borgo and Fiume Dei Nobili) supply a walkable environment due to low-rise building stock, pedestrian-oriented management of local mobility, and clear hierarchy and functional mix, with residence as the prevailing use. According to the scores associated with the different performance levels, the perception of safety seems rather critical (for example, in 90% of the neighbourhoods, crossings signs and markings are not adequate; in 80% of the areas, the sidewalks are not present or are inadequate). The unsuitability of some environmental factors (especially vegetation and waters, density of intersections, density of public transport, the presence of cycling and pedestrian paths, sidewalks, etc.) is clearly detrimental to the salutogenicity of the neighbourhoods [3]; these, along with the poor enforcement of LTZs (missing in 80% of the areas), and pedestrianized areas (unavailable for 60%), no cycle paths or seats (everywhere in the case study), are additional barriers to support behavioural changes in favour of more physical activity levels and more active environments [56,66].

A focus on the Mobility performance might help to explain some of the barriers mentioned above. This is the bulkiest category, which describes the quality of connections and, in turn, is strongly affected by the urban fabric. It is not surprising, then, that Mobility highlights contrasting results. On the one hand, areas such as the city centre (District n. 10) are fully preserved by traffic phenomena by the enforcement of LTZ (although vehicular flows are not negligible, as surveyed in [63]), supplied with parking areas to avoid on-street parking, and pedestrianized to recreate the pristine HEI and enhance the cultural heritage. On the other, in areas where monofunctional land use (residence) is associated with modest or poor building quality, the Mobility features are consistently similar, with no walking-enhancing solutions: no LTZ and pedestrianization, basic transit supply, on-street parking, double lines and spill over. The paucity of Urban furniture and Natural elements are contributing factors in both cases, although with different outcomes. In the city centre, seating, public lighting, signs and marking are designed to highlight the premium built environment, which is so significant per se that natural elements are reduced to waterworks and sparse vegetation. In the contemporary districts, urban furniture is mostly reduced public lighting and road signs, mostly to prevent unsafe events. Vegetation, although richer, relies on small public parks and gardens, tree-lined streets and private areas, which help to increase the quality of the urban environment but not enough to trigger salutogenic behaviours.

4.2. The Overall Systemic Assessment—Levels 2 and 3 Analysis

The average value of ergonomics of Rieti obtained through the Bayesian model, expressed in percentage, is 44.2%, and Table 9 illustrates the score obtained by each neighbourhood. About 80% of the neighbourhoods have a low ergonomic level, which, therefore represent a widespread situation in the city of Rieti. Through a backward analysis (i.e., by observing the lower value on the Ergonomics node—see Figure 7), it is possible to identify the causes of the overall poor performance for the Rieti town. The analysis of the individual indicators (Table 8) highlights significant deficiencies, especially in terms of public transport, cycle paths and street furniture; the presence of green areas and the cleanliness of the urban space are also lacking. All these factors can be easily improved through a review of local land use planning policies [83,84]. At present, however, the lack of the aforementioned environmental factors determines the critical issues in terms of indicators related to the ability to walk and more generally to physical activity [3,63].

A further analysis can be conducted, selectively observing different values of the neighbourhood node. In that way, it is possible to compare the statistics of the different neighbourhoods, to highlight specific deficiencies and to identify possible improvements. As we have already pointed out, the explanations of complex states of affairs can affect the representation of boundaries of the probabilistic model.

For example, on one side, the Centro Storico shows the highest value of the ergonomics score (57.1%—Table 10). This can be explained in terms of several interventions already realized by the public administration in that area to increase its ability to attract people and to improve the economy. On the other side, however, the same neighbourhood shows poor performance in some inner nodes that can be explained only through the topology of the network. In fact, the lack of public transport shows, in the Centro Storico case, a strong correlation to the olfactory perception nodes and to the presence of traffic (Figure 7), providing a clear hint of the unpleasant smells generated by unbalanced traffic patterns.

Table 10.

Neighbourhoods’ ergonomics obtained using a discrete Bayesian network and level of ergonomics of each component in the investigated neighborhoods.

A second noteworthy example is the Villa Reatina neighbourhood, where the worst situation is observed (36.6%—Table 9). Villa Reatina is considered a working-class neighbourhood whose first urbanization dates back to the fascist period and expanded in the following years. It is mainly a residential area, consisting of one or two-family buildings (built from 1920 to 1940) and multi-family buildings (built from 1960 to 1990), most of which fall within economic and popular building projects [54.6%]. It is a neighbourhood where social inequalities are particularly evident due to both the origin of the neighbourhood and its urban conformation. The Bayesian Network model shows that the low level of ergonomics is determined by equally scarce values of usability, well-being and safety (worst value). Proceeding backwardly on the BNet model, it is possible to identify the causes that are the prime factors determining such a low level of ergonomics. In the neighbourhood, at present, there are several shortcomings, mainly related to the urban structure that compromise the aesthetic quality of the neighbourhood and its liveability (lack of identity and recognizability). They include lack of hierarchical relations among spaces, both formal and dimensional, poorly defined urban margin and connectivity between the various parts of the neighbourhood, etc. As for the historic centre, shortcomings are identified in public transport, in cycling networks, in pedestrian crossings and, more generally, in the design of urban space dedicated to pedestrians (lack of seats, lighting, etc.).

4.3. General Trends

Finally, it is worth annotating some general trends concerning salutogenicity that can be identified from this level of analysis.

4.3.1. Environmental Factors

Environments with poor environmental and aesthetic quality could greatly influence the lifestyle of the population and be perceived as unsafe. The lack of environmental factors that support physical activity pushes Villa Reatina to the worst ergonomics rank and to the fifth to last in walkable neighbourhood among those studied. In fact, urban and indoor environments represent one of the major health determinants, and a clear and updated regulatory system is a key factor to ensure not only Public Health safeguarding [84], but also more sustainable mobility patterns.

4.3.2. The Safety Issues

Table 9 shows the ergonomics scores, stratified by their principal components (Usability, Well-Being and Safety). According to previous studies [12,24], Safety obtains the lowest scores in all the neighbourhoods. Results achieved for Safety, as “the set of conditions related to the safety of users, as well as to the defence and prevention of damage caused by accidental factors, in the operation of the urban outdoor space system” [85], highlight once more the relevance of Mobility in promoting sustainable travel habits. In particular, the factors determining the low safety score are mainly related (Figure 7) to the lack of public transport and cycle paths (both with insufficient scores in 100% of the districts), crossings (insufficient in 90% of districts), pedestrian areas and limited traffic areas (both insufficient in 80% of districts). These aspects, addressed within local general mobility policies [86,87], should be taken into account and solved into the Urban Traffic Plans (UTPs) and Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMPs), by means of specific actions, like those recently recommended by the WHO [2,88,89], as further discussed in Section 5.

The Safety issue introduces one more element to consider: the relevance of maintenance of paths and urban furniture to ensure proper and favourable walking conditions and to avoid accidents and falls. Several studies on areas similar to those in the case study [64,90,91] stressed how maintenance, if neglected, generates inappropriate walking behaviours among the pedestrians, thus reducing the overall walkability of an area. This means that walkability needs an integrated management (land use policies, mobility regulations, maintenance plans), which the BNet applications might help to foster by highlighting the several interrelations between the HEI other variables.

The use of the BNets provides a complete framework of the current situation in the neighborhoods, highlighting the causes that determine the above-mentioned ergonomic results in the various areas.

4.3.3. The Well-Being Issue

The factors involved in the definition of the districts’ wellbeing also obtained insufficient scores. Well-being, as defined by the WHO (“a state of total physical, mental and social well-being” and not simply “absence of disease or infirmity” [87]), in the study was intended primarily as “the set of conditions relating to states of the open urban spaces system adequate to life, health and the performance of the inhabitants’ activities” [40].

The conditions of well-being, as stated in the norm [88], refer to the positive sensory perception of the environment by the user, to health and hygiene situations, to the absence of pathogenic conditions and to the safety of users. If the user’s satisfaction represents the level of comfort that is perceived in the performance of daily activities in an open space, the concept of well-being can be conditioned, since it is connected (Figure 7) to the factors that define the use and safety of the spaces in carrying out the activities. Several variables negatively affect the Well-being scores; some of them still due to Mobility issues (the lack of public transport, of bicycle paths, limited traffic areas, crossing). In addition, the inadequate management and maintenance of public roads (with insufficient scores in 90% of the districts), cleaning of outdoor spaces (insufficient in 100% of the districts), as well as approximate street furniture (lack of seats and suitable signs in 100% of the districts) are equally lacking.

4.3.4. Mobility

Mobility has a central role in generating salutogenic cities according to the HEI approach. Both the results from the indicators and the BNet analyses evidence how unbalanced traffic patterns in favour of private traffic are detrimental to Safety in general and in some specific areas within Well-being and Usability. Hence, an appropriate Mobility governance should be adopted, starting from the enforcement of its sustainability-oriented regulatory tools. The usual regulatory tools are those to manage traffic flows and to develop sustainable mobility patterns (fully described in the literature [89] and largely enforced across Europe).

As shown by scores achieved in the city centre and in the other neighbourhoods in the case study, pedestrianization, LTZs and Zone 30s can be considered unavoidable interventions to safeguard and rehabilitate premium value environments in central historic areas and, in general, to enhance walking even in areas where the built environment may lack distinct qualities.

5. Discussing Possible Advances

The methodology described in Section 2 relies on the reported array of measurable indicators to assess the salutogenicity of a given urban context. However, cities are complex, each with different local features and living conditions. Such specificities introduce three issues to address as possible areas of advancement in the proposed methodology: i) once more, the relevance of selecting SMART indicators, but also the possibility of creating flexible tools, adaptable to the most different of urban contexts by adding more parameters; and ii) the possibility of enlarging the analysis by contemplating non-physical aspects like the human or social environments, and iii) the need to include different categories of surveyors in the analysis.

For what concerns the first issue, the HEI approach makes it possible to freely add to, or remove from, the selected categories more indicators than those used for this case study, if need be, thus tailoring the assessment and further fine-tuning the overall analysis to any case in hand. The evaluation of land use as an element affecting the walkability of a given urban environment is a case in point. In the literature, the assessment of land use is often assumed in terms of dominant functions, thus replicating the approach usually applied in urban planning. Consequently, an area can be assessed in terms of land use mix, by measuring the availability of its main uses: residential, commercial, etc. This is certainly a major determinant, as, in the literature, it has been long-acknowledged that monofunctional uses are detrimental to livability, based on specific indicators like, for example, land use entropy [92]. However, these types of indicators. although accurate, call for extensive data process [82,92], are area-based and do not consider local effects at the ground level generated by bustling storefronts, street activities, and outdoors-based behaviors [67,79]. These contribute to urbanity, i.e., those specific characteristics of urban life, and placing an emphasis on indicators measuring the vibrancy of the city life at the ground level results in an added-value to the walkability assessment. Some urbanity indicators describing the sidewalks’ levels of service (width, types of equipment) to accommodate the street activities were already developed for this case study and fully described in [61], but, in the literature, more can be found associated, for example, with: Trip-Generating Clusters (i.e., the capacity of given urban activities and facilities to generate the displacement of pedestrians); buildings’ variety of formal features as elements to support walking (mostly space syntax-based, such as: Mean Convex Space; Mean Number of Entrances per Convex Space; Percentage of Blind Convex Spaces, etc.) [93]; landscape and environmental metrics (based on the quality of vegetation and pollutants’ concentrations) [94]; participation in public life (as revealed preferences) [95].

The relevance of participation introduces the second issue, i.e., the possibility of highlighting how the human and social environments affect this type of study. Additionally, in this case, more indicators can be easily introduced than those used for the case in hand, which were derived by the local situation: Rieti is a typical middle-size European provincial town, with modest crime rates, no social conflicts, poor-quality but still livable outskirts, and welfare problems rarely experienced. Thus, the difference in this matter between the city center and the surrounding districts relies mostly on the former’s higher quality of built environment over the latter’s, and its natural vocation as a walking environment is also preserved by the enforcement of the local LTZ. Here, a consolidated land use based mostly on a mix of commercial facilities at the ground level and residential use on the upper stories, which attracts locals and visitors from the surrounding cities for most of the day, also helps to keep the area alive and avoid decadence. On the contrary, in urban areas with marked social inequalities among the city center and the other neighbourhoods (the former being either too exclusive with high-value properties and tourism-gentrified, or too dilapidated due to subpar building stock, security and safety problems, and inhabited by less and less affluent residents and businesses), more indicators and additional analyses are certainly needed. Again, in the literature, indicators to assess the role of the social environment that are consistent with the HEI approach abound and can cover all the contemplated categories. For example, indicators assessing social costs of transport, public perception and awareness, and safety levels [96,97] are appropriate to highlight the relationships between social inclusion and mobility. The approach in [98] seems to be particularly germane to assess how inequalities can be generated by natural and built environment features (by considering indicators assessing vegetation planting, access to green and recreational areas, on the one hand, and the effect of foreclosure, homeownership or vacancy rates on the other). Eventually, surveys based on Revealed and Stated Preferences can give rise to accurate assessment of how citizens perceive the environments they inhabit and the quality of the supplied services and equipment.

As described in Section 2.1.1, both the survey and the data process for the case study were carried out by researchers, so to achieve an expert assessment as a research goal. However, consistently with the HEI approach and the easiness of scoring the performance via the lists presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, the assessment can be extended to the real users, i.e., the neighborhoods’ inhabitants. This opportunity, currently under study, calls for the voluntary involvement of different users’ categories (according to age, gender, special needs). Perceptions vary not only with physical status but with familiarity with the urban context, trip purposes, weather conditions. All of the above will be considered to design accurate survey conditions and ensure comparability of the prospective results with those already available. Involving citizens represents a two-fold added-value as it complements the expert assessment and provides specific insights according to the actual abilities of the participants.

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper has discussed the salutogenicity issue of urban environments and its relationship with urban ergonomics, focusing on mobility and walkability. The paper has proposed a methodology to define generalized statistical models of urban ergonomics and salutogenicity, has introduced and discussed the relevant parameters derived from the large sets proposed in the literature, has discussed the emerging structure of a multi-level Bayesian network model, and has provided evidence of the solution’s effectiveness through an in depth discussion of the modelling result. The methodology has been applied to the city of Rieti, a middle-sized town in central Italy.

Although the model has been able to provide consistent snapshots of the actual state of affairs of the case study, and has supported interpretations and diagnoses of the emerging performance gaps, further work is still necessary to extend this methodology to provide a more generalised approach and consider the possible advances highlighted in Section 5. Moreover, a preliminary first principle modelling approach, developed exclusively using equations and parameters derived from the literature, shown, in our case study, scarce correlations among the various parameters, making the resulting model relatively unusable. On the other side, a second, purely data-driven approach gave a perfect image of the state of the matter, which, possibly due to overfitting, was hardly generalizable to other cases. The mixed data-driven plus first principle approach presented in this paper provided the best trade-off between accuracy and generality. However, further studies are still necessary to consolidate the methodology and the possibility of including more indicators, as stressed in Section 5, will contribute to mitigating the elements of uncertainty.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A., D.D., and M.V.C.; Data curation, L.A. and A.G.; Supervision, D.D. and A.G.; Writing—original draft, L.A. and A.G.; Writing—review and editing, D.D., M.V.C., and L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Saving Lives, Spending Less: A Strategic Response to Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018/2030m More Active People for Healthier World; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Capolongo, S.; Rebecchi, A.; Dettori, M.; Appolloni, L.; Azara, A.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Casuccio, A.; Oliveri Conti, G.; D’Amico, A.; et al. Healthy design and urban planning strategies, actions, and policy to achieve salutogenic cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Diseases: A Vital Investment: WHO Global Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, J.; Woodcock, J.; Griffiths, U.K.; Chalabi, Z.; Edwards, P.; Roberts, I.; Haines, A. Effect of increasing active travel in urban England and Wales on costs to the National Health Service. Lancet 2012, 379, 2198–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.; Eiben, G.; Lauria, F.; Konstabel, K.; Page, A.; Ahrens, W.; Pigeot, I. Urban Moveability and physical activity in children: Longitudinal results from the IDEFICS and I.Family cohort. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, G.R.; Cabaj, J.; Orpana, H.; Lukic, R.; Blackstaffe, A.; Goopy, S.; Hagel, B.; Keough, N.; Martinson, R.; Chapman, J.; et al. A scoping review on the relations between urban form and health: A focus on Canadian quantitative evidence. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. Res. Policy and Pract. 2019, 39, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Influence of urban and transport planning and the city environment on cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, E.L.; Ige, J.O.; Pilkington, P.; Pinto, A.; Petrokofsky, C.; Burgess-Allen, J. Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley, R.; Blakely, T.; Kavanagh, A.; Aitken, Z.; King, T.; McElwee, P.; Giles, C.B.; Turrel, G. A longitudinal study examining changes in street connectivity, land use, and density of dwellings and walking for transport in Brisbane, Australia. Environ. Health Perspect. 2018, 126, 057003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuiman, M.W.; Christian, H.E.; Divitini, M.L.; Foster, S.A.; Bull, F.C.; Badland, H.M.; Giles-Corti, B. A longitudinal analysis of the influence of the neighborhood built environment on walking for transportation: The RESIDE study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 180, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schipperijn, J.; Ried-Larsen, M.; Nielsen, M.S.; Holdt, A.F.; Grontved, A.; Ersboll, A.K.; Kristensen, P.L. A longitudinal study of objectively measured built environment as determinant of physical activity in young adults: The European youth heart study. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2015, 12, 909–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.; Reynolds, C.C.O.; Winters, M.; Cripton, P.A.; Shen, H.; Chipman, M.L.; Cusimano, M.D.; Babul, S.; Brubacher, J.R.; Friedman, S.M.; et al. Comparing the effects of infrastructure on bicycling injury at intersections and non-intersections using a case–crossover design. Inj. Prev. 2013, 19, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Frank, L.D.; Pratt, M.; Salvo, D.; Schipperijn, J.; Smith, G.; Cain, K.L.; et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: A corss-sectional study. Lancet 2016, 387, 2207–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Towards More Physical Activity in Cities Transforming Public Spaces to Promote Physical Activity—A Key Contributor to Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals in Europe; BMC Public Health: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Chapman, J.E.; Saelens, B.E.; Bachman, W. Many pathways from land use to health: Associations between neighborhood walkability and active transportation, body mass index, and air quality. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J.; Spence, J.C.; Mummery, W.K. Perceived environment and physical activity: A meta-analysis of selected environmental characteristics. Int. J. Behav. Nutr.Phys. Act. 2005, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beenackers, M.A.; Foster, S.; Kamphuis, C.B.; Titze, S.; Divitini, M.; Knuiman, M.; van Lenthe, F.J.; Giles-Corti, B. Taking up cycling after residential relocation: Built environment factors. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congiu, T.; Sotgiu, G.; Castiglia, P.; Azara, A.; Piana, A.; Saderi, L.; Dettori, M. Built environment features and pedestrian accidents: An italian retrospective study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, S.; Sajadzadeh, H.; Sheshkal, F.M.; Aram, F.; Pinter, G.; Felde, I.; Mosavi, A. The role of urban morphology design on enhancing physical activity and public health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvetsov, Y.B.; Shariff-Marco, S.; Yang, J.; Conroy, S.M.; Canchola, A.J.; Albright, C.L.; Park, S.; Monroe, K.R.; le Marchanda, L.; Gomez, S.L.; et al. Association of change in the neighborhood obesogenic environment with colorectal cancer risk: The Multiethnic Cohort Study. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerin, E.; Conway, T.L.; Adams, M.A.; Barnett, A.; Cain, K.L.; Owen, N.; Christiansen, L.B.; van Dyck, D.; Josef, M.; Sarmiento, O.L.; et al. Objectively-assessed neighbourhood destination accessibility and physical activity in adults from 10 countries: An analysis of moderators and perceptions as mediators. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 211, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Arletti, S.; Azara, A.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Cappuccitti, A.; Casuccio, A.; Cecchini, A.; Costa, G.; De Martino, A.M.; et al. Strategies for disease prevention and health promotion in urban areas: The erice 50 charter. Ann. Ig. 2017, 29, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chum, A.; O’Campo, P. Cross-sectional associations between residential environmental exposures and cardiovascular diseases. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malambo, P.; Kengne, A.P.; De Villiers, A.; Lambert, E.V.; Puoane, T. Built environment, selected risk factors and major cardiovascular disease outcomes: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, H.; Heiss, G.; Rose, K.M.; Whitsel, E.A.; Lurmann, F.; London, S.J. Prospective analysis of traffic exposure as a risk factor for incident coronary heart disease: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Environ Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 1463–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, T.R.; Spence, J.C.; Blanchard, C.; Cutumisu, N.; Edwards, J.; Nykiforuk, C. Changes in BMI over 6 years: The role of demographic and neighborhood characteristics. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfinkel-Castro, A.; Kim, K.; Hamidi, S.; Ewing, R. Obesity and the built environment at different urban scales: Examining the literature. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.B.; Yamada, I.; Smith, K.R.; Zick, C.D.; Kowaleski-Jones, L.; Fan, J.X. Mixed land use and walkability: Variations in land use measures and relationships with BMI, overweight, and obesity. Health Place 2009, 15, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, R.P.; Hynes, P.H. Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: Public health research needs. In Urban Health: Readings in the Social, Built, and Physical Environments of U.S. Cities; Hynes, H.P., Lopez, R., Eds.; Jones and Bartlett: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 169–185. [Google Scholar]

- Toker, Z. Walking beyond the socioeconomic status in an objectively and perceptually walkable pedestrian environment. Urban Studies Res. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolongo, S.; Rebecchi, A.; Buffoli, M.; Appolloni, L.; Signorelli, C.; Gaetano, M.; Daniela, D.A. COVID-19 and cities: From urban health strategies to the pandemic challenge. A decalogue of public health opportunities. Acta Biomed. 2020, 9, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Fara, G.M.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S. Green areas and public health: Improving wellbeing and physical activity in the urban context. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ngom, R.; Gosselin, P.; Blais, C.; Rochette, L. Type and proximity of green spaces are important for preventing cardio-vascular morbidity and diabetes—A cross-sectional study for Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triguero-Mas, M.; Gidlow, C.J.; Martínez, D.; de Bont, J.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Martínez-Íñiguez, T.; Hurst, G.; Masterson, D.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Seto, E.; et al. The effect of randomised exposure to different types of natural outdoor environments compared to exposure to an urban environment on people with indications of psychological distress in Catalonia. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Mavoa, S.; Villanueva, K.; Sugiyama, T.; Badland, H.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Owen, N.; Giles-Corti, B. Public open space, physical activity, urban design and public health: Concepts, methods and research agenda. Health Place 2015, 33, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siiba, A. Active travel to school: Understanding the Ghanaian context of the underlying driving factors and the implications for transport planning. J. Transp. Health 2020, 18, 100869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M.J. Urban and transport planning pathways to carbon neutral, liveable and healthy cities; A review of the current evidence. Environ. Int. 2020, 140, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenbach, J.D.; Randal, E.; Zhao, P.; Howden-Chapman, P. The Influence of Urban Land-Use and Public Transport Facilities on Active Commuting in Wellington, New Zealand: Active Transport Forecasting Using the WILUTE Model. Sustainability 2016, 8, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, M.V.; Guida, U.; Musso, A.; Tozzi, M. From EBSF to EBSF-2: A compelling agenda for the bus of the future: A decade of research for more attractive and sustainable buses. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering (EEEIC), Florence, Italy, 7–10 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corazza, M.V.; Musso, A.; Karlsson, M.A. More accessible bus stops: Results from the 3ibs research project. In More Accessible Bus Stops Proceedings of the AIIT International Congress on Transport Infrastructure and Systems, Rome, Italy, April 10-12-2017; Wegman, F., Dell’Acqua, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Balkema, London, 2017; pp. 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- Unger, S.D. Integrating CBR and BN for Decision Making with Imperfect Information. Master’s Thesis, Norvegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, M.M.; Weber, R.O. Case Based Reasoning; Spinger: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerulff, U.B.; Anders, L.M. Bayesian networks and influence diagrams. Springer Sci. Bus. Media 2008, 200, 114. [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow Centre for Population Health. The Built Environment and Health: An Evidence Review; GCPH: Glasglow, UK, 2013; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Brownson, R.C.; Hoehner, C.M.; Day, K.; Forsyth, A.; Sallis, J.F. Measuring the built environment for physical activity. state of the science. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2009, 36, S99–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, L.D.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Lauren, L.; Cain, K.; Conway, T.L.; Hess, P.M. The development of a walkability index: Application to the neighborhood quality of life study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009, 44, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles-Corti, B.; Donovan, R.; Holman, C. Factors influencing the use of physical activity facilities: Results from qualitative research. Health Promot. J. Aust. 1996, 6, 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Handy, S. Measuring the unmeasurable: Urban design qualities related to walkability. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Environment at a Glance Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD Work on Measuring Well-Being and Progress towards Green Growth. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sdd/rioplus20%20to%20print.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- WHO Europe. Core Health Indicators in the WHO Europe Region. 2019. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/413239/CHI_2019_EN_WEB.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2020).

- World Health Organization. Development of Environment and Health Indicators for European Union Countries: Results of a Pilot Study: Report on a WHO Working Group Meeting. Bonn, Germany, 7–9 July 2004. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107620 (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Spiekermann, K.; Wegener, M. Modelling Urban Sustainability. Available online: http://www.spiekermann-wegener.de/pub/pdf/PROPOLIS_IJUS.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2019).

- D’Alessandro, D.; Assenso, M.; Appolloni, L.; Cappuccitti, A. The Walking Suitability Index of the Territori (T-WSI): A new tool to evaluate urban neighborhood walkability. Ann. Ig. 2015, 27, 678–687. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Appolloni, L.; Capasso, L. How walkable is the city? Application of the walking Suitability Index of the Territory (T-WSI) to the city of Rieti (Lazio Region, Central Italy). Epidemiol. Prev. 2016, 40, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://iea.cc/what-is-ergonomics/ (accessed on 9 October 2020).

- Dul, J.; Bruder, R.; Buckle, P.; Carayon, P.; Falzon, P.; Marras, W.S.; Wilson, J.R.; van der Doelen, B. A strategy for human factors/ergonomics: Developing the discipline and profession. Ergonomics 2012, 55, 377–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.R. Fundamentals of ergonomics in theory and pactice. Appl. Ergon. 2014, 45, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, R.P.; Quillien, J. A search for beauty/a struggle with complexity: Christopher alexander. Urban Sci. 2019, 3, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffagnini, M. Progettare Nel Processo Edilizio; Edizioni Luigi Parma: Bologna, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Appolloni, L.; D’Alessandro, S.; Cecere, C.; Patrizio, P. Ergonomics of Urban Areas: Testing a System for Multi-Criteria Evaluation; EdicomEdizioni: Monfalcone, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Appolloni, L.; Corazza, M.V.; D’Alessandro, D. The pleasure of walking: An innovative methodology to assess appropriate walkable performance in urban areas to support transport planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, M.V.; Di Mascio, P.; D’Alessandro, D.; Moretti, L. Methodology and evidence from a case study in Rome to increase pedestrian safety along home-to-school routes. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engwicht, D. Reclaiming Our Cities and Town; New Society Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.W. Activity, exercise and the planning and design of outdoor spaces. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Kaczynski, A.T.; Giles-Corti, B.; Karakiewicz, J.A. Effects of access to public open spaces on walking: Is proximity enough? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 117, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, G.K.W.; Van Niel, K.P.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M. Accessibility and connectivity in physical activity studies: The impact of missing pedestrian data. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Manaugh, K.; Kreider, T. What is mixed use? Presenting an interaction method for measuring land use mix. J. Transp. Land Use 2013, 6, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.; Cauwenberg, J.V.; Hercky-Linnewiel, R.; Deforche, B.; Plaut, P. Understanding the relationships between the physical environment and physical activity in older adults: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koohsari, M.J.; Sugiyama, T.; Lamb, K.E.; Villanueva, K.; Owen, N. Street connectivity and walking for transport: Role of neighborhood destinations. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebecchi, A.; Buffoli, M.; Dettori, M.; Appolloni, L.; Azara, A.; Castiglia, P.; D’Alessandro, D.; Capolongo, S. Walkable Environments and Healthy Urban Moves: Urban Context Features Assessment Framework Experienced in Milan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczynski, A.; Mohammad, J.K.; Wilhelm Stanis, S.A.; Bergstrom, R.; Sugiyama, T. Association of street connectivity and road traffic speed with park usage and park-based physical activity. Am. J. Health Promot. 2014, 28, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, C.L.; Sayers, S.P.; Wilhelm Stanis, S.A.; Thombs, L.A.; Thomas, I.M.; Canfield, S.M. The Impact of a Signalized Crosswalk on Traffic Speed and Street-Crossing Behaviors of Residents in an Underserved Neighborhood. J. Urban Health 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Monteiro, F.B.; Campos, V.B.G. A Proposal of Indicators for Evaluation of the Urban Space for Pedestrians and Cyclists in Access to Mass Transit Station. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 54, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mertens, L.; Van Holle, V.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Salmon, J.; Nasar, J.; Van de Weghe, N.; Van Dyck, D.; Van Cauwemberg, J. The effect of changing micro-scale physical environmental factors on an environment’s invitingness for transportation cycling in adults:an exploratory study using manipulated photographs. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Physical activity strategy for the WHO European Region 2016–2025; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gehl, J. Life between Buildings, Using Public Space; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Valcovich, E.; Fernetti, V.; Stival, C.A. Un Approccio Ecosostenibile alla Progettazione Edilizia. Il Protocollo di Valutazione Energetico-Ambientale (VEA) della Regione Friuli Venezia Giulia; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, G.T. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manag. Rev. 1981, 70, 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Corazza, M.V.; Favaretto, N. A methodology to evaluate accessibility to bus stops as a contribution to improve sustainability in urban mobility. Sustainability 2019, 11, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Appolloni, L.; Capasso, L. Public health and urban planning: A powerful alliance to be enhanced in Italy. Ann. Ig. 2017, 29, 453–463. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, V.I.; Capasso, L.; Klepikov, O.V.; Appolloni, L.; D’Alessandro, D. Hygienic Requirements of Urban Living Environment in the Russian Federation and in Italy: A comparison. Ann. Ig. 2018, 30, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UNI 11277:2008. Sostenibilità in Edilizia—Esigenze e Requisiti di Ecocompatibilità dei Progetti di Edifici Residenziali e Assimilabili, Uffici e Assimilabili, di Nuova Edificazione e Ristrutturazione. Available online: http://store.uni.com/catalogo/uni-11277-2008?josso_back_to=http://store.uni.com/josso-security-check.php&josso_cmd=login_optional&josso_partnerapp_host=store.uni.com (accessed on 8 October 2019).

- Capasso, L.; Faggioli, A.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S.; Gaeta, M.; Appolloni, L.; De Martino, A.; D’Alessandro, D. Hygienic and sanitary aspects in urban planning: Contradiction in national and local urban legislation regarding public health. Epidemiol. Prev. 2018, 42, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lopez Lambas, M.E.; Corazza, M.V.; Monzon, A.; Musso, A. Rebalancing urban mobility: A tale of four cities. Urban Des. Plan. 2013, 166, 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of World Health Organization (WHO); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.D.; Schmid, T.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Chapman, J.; Saelens, B.E. Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: Findings from SMARTRAQ. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ragnoli, A.; Corazza, M.V.; Di Mascio, P.; Musso, A. Maintenance priority associated to powered two-wheeler safety. WIT Trans. Built Environ. 2017, 176, 453–464. [Google Scholar]

- Ragnoli, A.; Corazza, M.V.; Di Mascio, P. Safety ranking definition for infrastructures with high PTW flow. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2018, 5, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervero, R.; Kockelman, K. Travel demand and the 3Ds: Density, diversity, and design. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 1997, 2, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuto, R.; Amorim, L. Establishing parameters for urbanity. In Eighth International Space Syntax Symposium; Greene, M., Reyes, J., Castro, A., Eds.; PUC: Santiago, Chile, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, M.; Scaletta, K.L.; James, P. Evaluating urban environmental and ecological landscape characteristics as a function of land-sharing-sparing, urbanity and scale. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Diepen, A.M.L.; Musterd, S. Lifestyles and the city: Connecting daily life to urbanity. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2009, 24, 331–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, H.; Pitfield, D.E. ELASTIC—A methodological framework for identifying and selecting sustainable transport indicators. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2010, 15, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency. Paving the Way for EU Enlargement—Indicators of Transport and Environment Integration TERM 2002; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A.J.; Mosbah, S.M. Improving local measures of sustainability: A study of built-environment indicators in the United States. Cities 2017, 60, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).