Reflecting SDG 6.1 in Rural Water Supply Tariffs: Considering ‘Affordability’ Versus ‘Operations and Maintenance Costs’ in Malawi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Context, Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Dataset Sampling

2.4. Methods

- Service Delivery—Describing the type of service provider and number of users.

- Operational—Describing the age and functionality of an asset, preventative maintenance, and if spare parts are kept on site.

- Financial & Cost Recovery—Specifying the tariff amount and frequency.

- Geographical—Specifying the region of Malawi.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Decentralised Service Provision

3.2. Frequency of Tariff Collection

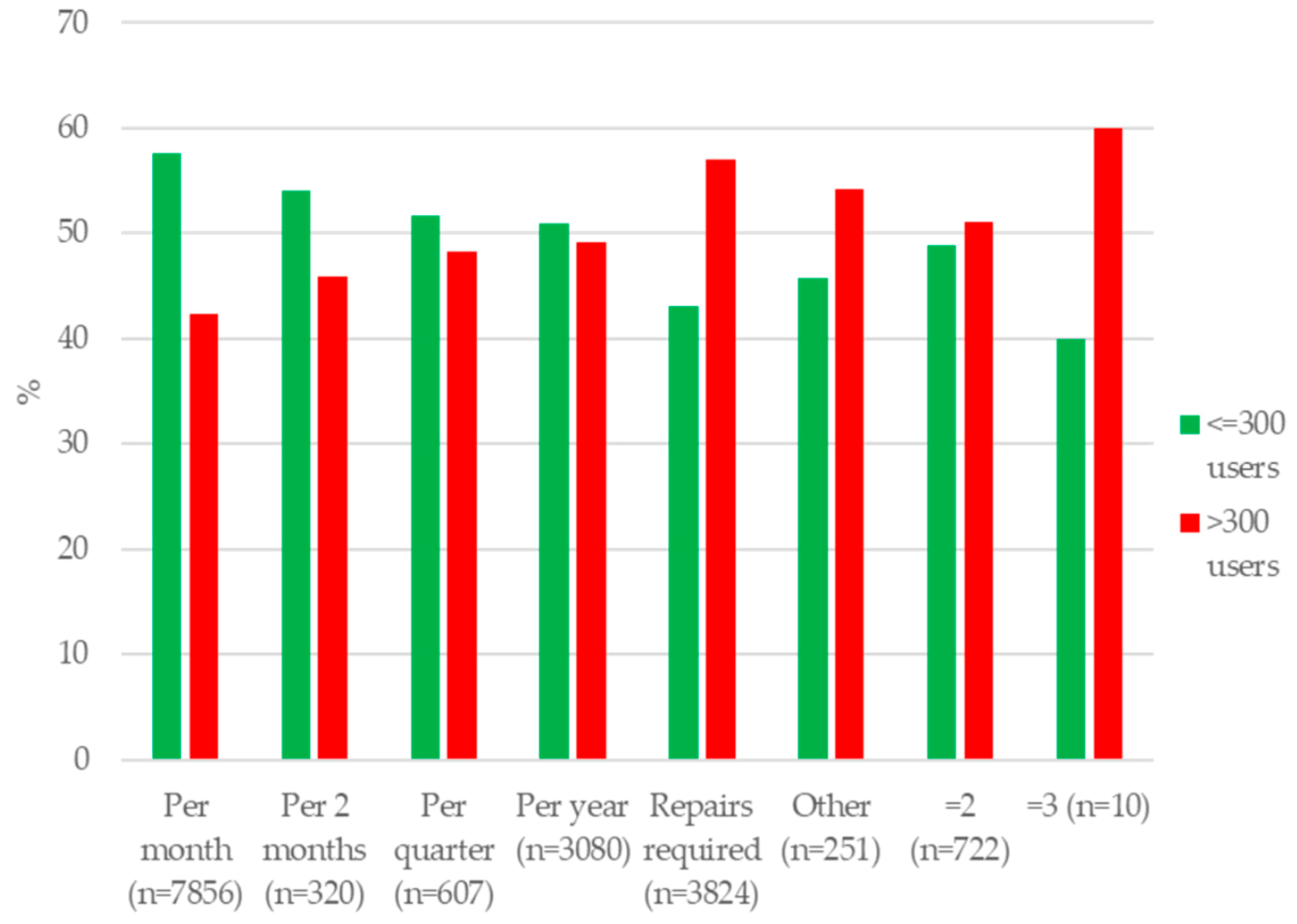

3.2.1. Frequency Distribution by Users

3.2.2. Frequency Distribution by Tariff Amount

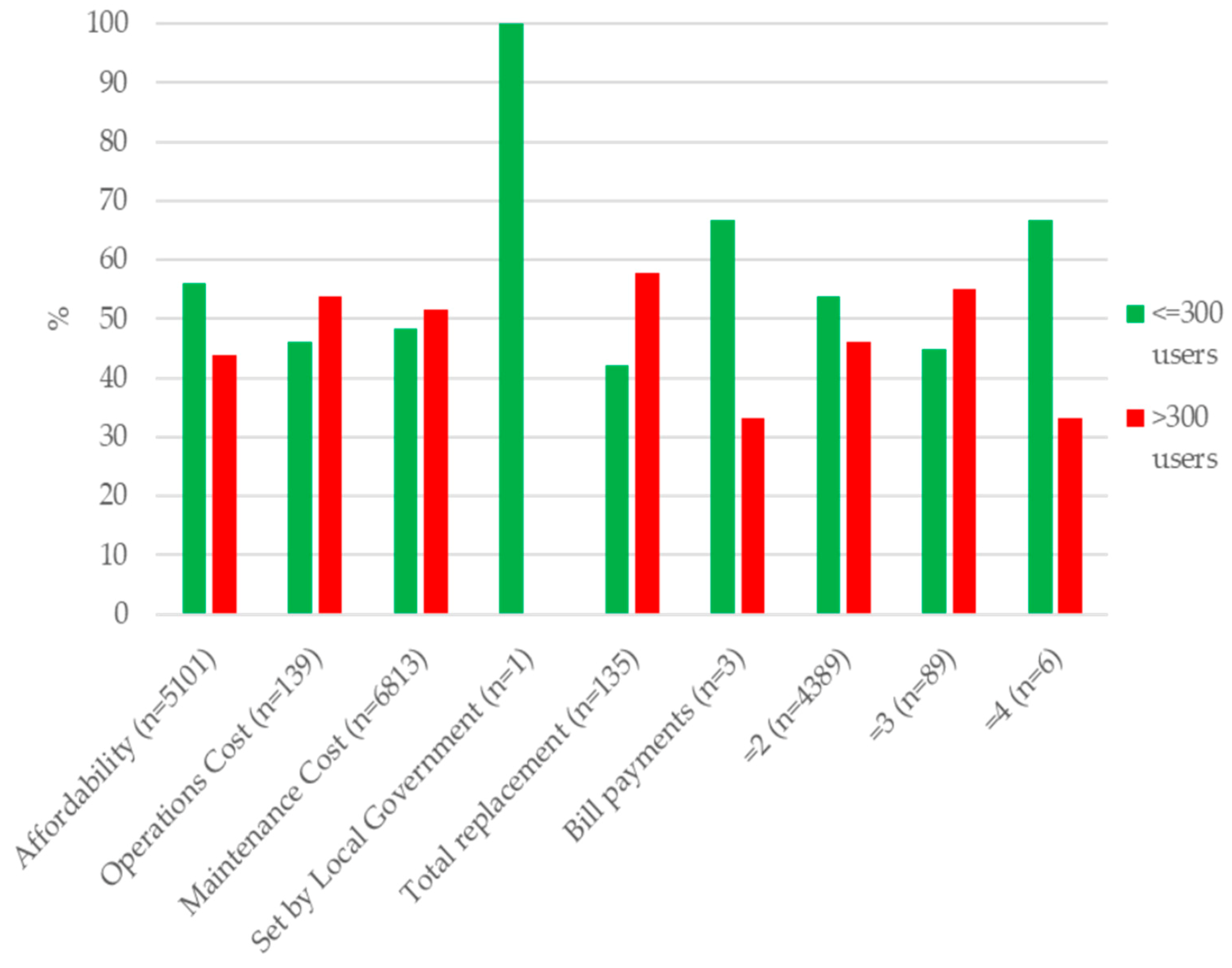

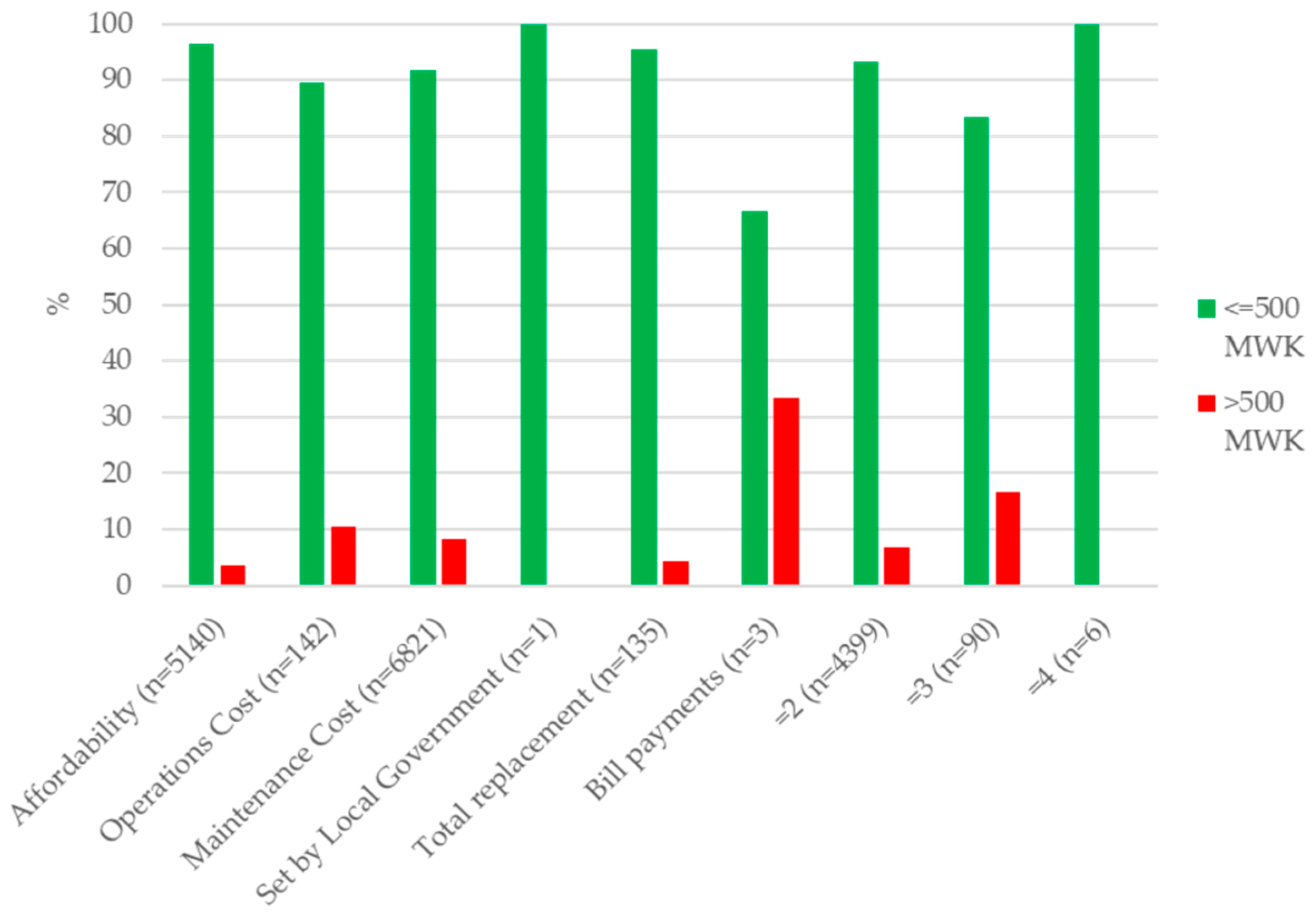

3.3. Considerations When Setting Tariffs

3.3.1. Considering Affordable and Maintenance Driven Tariffs

3.3.2. Considerations for Long Term Sustainability

4. Binary Logistic Regression—Affordability and O&M

4.1. Service Delivery—Service Providers and Maintenance

4.2. Financial Resources—Tariff Frequency, Tariff Amount, and Users

4.3. Malawian Assets—Region, Age, and Functionality

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Region of Malawi | District of Malawi | n | % of Total Data Set |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern | Balaka | 1126 | 5.05 |

| Blantyre | 1033 | 4.63 | |

| Chikwawa | 1039 | 4.66 | |

| Chiradzulu | 504 | 2.26 | |

| Machinga | 1012 | 4.53 | |

| Mangochi | 2953 | 13.2 | |

| Mulanje | 389 | 1.74 | |

| Mwanza | 337 | 1.51 | |

| Neno | 175 | 0.78 | |

| Nsanje | 327 | 1.47 | |

| Phalombe | 527 | 2.36 | |

| Thyolo | 841 | 3.77 | |

| Zomba | 1363 | 6.11 | |

| Total of Southern | 11,626 | 52.1 | |

| Central | Dedza | 1377 | 6.17 |

| Dowa | 1299 | 5.82 | |

| Kasunga | 1164 | 5.22 | |

| Lilongwe | 3179 | 14.2 | |

| Mchinji | 504 | 2.26 | |

| Nkhotakota | 679 | 3.04 | |

| Ntcheu | 1207 | 5.41 | |

| Ntchisi | 419 | 1.88 | |

| Salima | 646 | 2.89 | |

| Total of Central | 10,474 | 46.9 | |

| Northern | Chitipa | 9 | 0.04 |

| Karonga | 28 | 0.13 | |

| Likoma | 3 | 0.01 | |

| Mzimba | 85 | 0.38 | |

| Nkhata Bay | 14 | 0.06 | |

| Rumphi | 28 | 0.13 | |

| Total of Northern | 167 | 0.75 | |

| No data | - | 49 | 0.22 |

| Total | - | 22,316 | 100 |

References

- WHO/UNICEF. Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water: Update 2010; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; pp. 1–55. ISBN 9789241563956. [Google Scholar]

- Adank, M.; Butterworth, J.; Godfrey, S.; Abera, M. Looking beyond Headline Indicators: Water and Sanitation Services in Small Towns in Ethiopia. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2016, 6, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truslove, J.P.; Miller, A.V.M.; Mannix, N.; Nhlema, M.; Rivett, M.O.; Coulson, A.B.; Mleta, P.; Kalin, R.M. Understanding the Functionality and Burden on Decentralised Rural Water Supply: Influence of Millennium Development Goal 7c Coverage Targets. Water 2019, 11, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goal 6 Synthesis Report on Water and Sanitation; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2006 beyond Scarcity: Power, Poverty and the Global Water Crisis; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bartram, J.; Brocklehurst, C.; Fisher, M.B.; Luyendijk, R.; Hossain, R.; Wardlaw, T.; Gordon, B. Global Monitoring of Water Supply and Sanitation: History, Methods and Future Challenges. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2014, 11, 8137–8165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO/UNICEF. Progress on Sanitation and Drinking Water—2015 Update and MDG Assessment. World Health Organ. 2015, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO/UNICEF. Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines; WHO/UNICEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are We Successful in Turning Trade-Offs into Synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, B.; Luukkanen, J.; Silveira, S.; Kaivo-oja, J. Evaluating Synergies and Trade-Offs among Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Explorative Analyses of Development Paths in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2018, 10, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.A.; Reed, R.A. Community-Managed Water Supplies in Africa: Sustainable or Dispensable? Community Dev. J. 2006, 42, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, P.; Smits, S.; Butterworth, J.; Franceys, R. Trend in Rural Water Supply: Towards a Service Delivery Approach. Water Altern. 2013, 6, 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, P.; Chan, M.Y.; Cuadrado, L.; Ezbakhe, F.; Mesa, B.; Tamekawa, C.; Franceys, R. A Systematic Review of Success Factors in the Community Management of Rural Water Supplies over the Past 30 Years. Water Policy 2015, 17, 963–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouten, T.; Moriarty, P.B. Community Water, Community Management: From System to Service in Rural Areas; ITDG: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, E.; Furey, S. How Three Handpumps Revolutionised Rural Water Supplies a Brief History of the India Mark II/III, Afridev and the Zimbabwe Bush Pump Rural Water Supply Network Field Note No 2013-1; RWSN: St Gallen, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Macarthur, J. Handpump Standardisation in Sub-Saharan Africa Seeking a Champion; RWSN: St Gallen, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- RWSN Executive Steering Committee. Myths of the Rural Water Supply Sector; RWSN: St Gallen, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broek, M.; Brown, J. Blueprint for Breakdown? Community Based Management of Rural Groundwater in Uganda. Geoforum 2015, 67, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowns, E. Is Community Management an Efficient and Effective Model of Public Service Delivery? Lessons from the Rural Water Supply Sector in Malawi. Public Adm. Dev. 2015, 35, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, H.; Smits, S. Supporting Rural Water Supply Moving towards a Service Delivery Approach; Practical Action Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, P.; Franceys, R.; Mekala, S.; Smits, S.; James, A.J. Revisiting the History, Concepts and Typologies of Community Management for Rural Drinking Water Supply in India. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 33, 152–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsor, H.; MacDonald, A.; Casey, V.; Carter, R.; Wilson, P. The Need for a Standard Approach to Assessing the Functionality of Rural Community Water Supplies. Hydrogeol. J. 2018, 26, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kativhu, T.; Mazvimavi, D.; Tevera, D.; Nhapi, I. Factors Influencing Sustainability of Communally-Managed Water Facilities in Rural Areas of Zimbabwe. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2017, 100, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.C.; Ross, I. Beyond ‘Functionality’ of Handpump-Supplied Rural Water Services in Developing Countries. Waterlines 2016, 35, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, E.S.; Fenner, R. Water Point Failure in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Value of a Systems Thinking Approach. Waterlines 2017, 36, 140–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klug, T.; Cronk, R.; Shields, K.F.; Bartram, J. A Categorization of Water System Breakdowns: Evidence from Liberia, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Uganda. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T. Predictors of Sustainability for Community-Managed Handpumps in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Uganda. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 12037–12046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Santos, P. Does 91% of the World’s Population Really Have “Sustainable Access to Safe Drinking Water”? Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 33, 514–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalin, R.M.; Mwanamveka, J.; Coulson, A.B.; Robertson, D.J.C.; Clark, H.; Rathjen, J.; Rivett, M.O. Stranded Assets as a Key Concept to Guide Investment Strategies for Sustainable Development Goal 6. Water 2019, 11, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, R.; Singini, W.; Gwayi, S. Comparative Evaluation of the Cost of Water in Northern Malawi: From Rural Water Wells to Science Education. Appl. Econ. 2016, 48, 4573–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Privatization, Water Access and Affordability: Evidence from Malaysian Household Expenditure Data. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 2121–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nature Publishing Group. Delivering on Sustainable Development. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. UN-Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking-Water (GLAAS) 2017 Report: Financing Universal Water, Sanitation and Hygiene under the Sustainable Development Goals; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Malawi. Malawi in Figures 2018 Edition; Government of Malawi: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2018.

- Briscoe, J.; de Ferranti, D. Water for Rural Communities—Helping People Help Themselves; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P.; Appleton, B. Community Management Today: The Role of Communities in the Management of Improved Water Supply Systems; IRC: Delft, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, C.; Smits, S.; Nyarko, K.; Naafs, A.; Franceys, R. Financing Capital Maintenance of Rural Water Supply Systems: Current Practices and Future Options; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MoAIWD. Rural Water Supply Operation and Maintenance Series 1: Community Based Management (O&M Refresher Course) Training Manual; Ministry of Agriculture, Irrigation and Water Development: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2015.

- MoAIWD. National Water Policy; MoAIWD: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2005.

- MoAIWD. Implementation Guidelines for Rural Water Supply and Sanitation; MoAIWD: Lilongwe, Malawi, 2010.

- Baumann, E. Do Operation and Maintenance Pay? Waterlines 2006, 25, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.V.M.; Nhlema, M.; Kumwenda, S.; Mbalame, E.; Uka, Z.; Feighery, J.; Kalin, R. Evolving Water Point Mapping to Strategic Decision Making in Rural Malawi. In Proceedings of the 41st WEDC International Conference, Nakuru, Kenya, 9–13 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ERPF, K. Afridev: Installation and Maintenance Manual for the Afridev Handpump. (Revision 2-2007), v. 2.; SKAT-RWSN, Ed.; Rural Water Supply Network: St Gallen, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Malawi. Market Centre and Rural Piped Water Supply and Sanititaion Programme. Available online: http://www.wesnetwork.org.mw/Documents/Manuals/G-WSS3_Guidelines_for_Establishment_of_WUA.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2016).

- National Statistical Office. 2018 Population and Housing Census Preliminary Report; National Statistical Office: Zomba, Malawi, 2018.

- Whaley, L.; Cleaver, F. Can ‘Functionality’ Save the Community Management Model of Rural Water Supply? Water Resour. Rural Dev. 2017, 9, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedachalam, S.; MacDonald, L.H.; Shiferaw, S.; Seme, A.; Schwab, K.J.; On behalf of PMA2020 investigators. Underreporting of High-Risk Water and Sanitation Practices Undermines Progress on Global Targets. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannix, N.; Norrie, J.; Paterson, F.; Nhlema, M.; Mleta, P.; Nkhata, M.; Wanangwa, G.J.; Kumwenda, S.; Clarke, D.; Kalin, R.M. Making the Case for Improved Planning, Construction and Testing of Water Supply Infrastructure in Malawi. In Proceedings of the 41st WEDC International Conference, Nakuru, Kenya, 9–13 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, E.; Shields, K.F.; Cronk, R.; Lee, K.; Behnke, N.; Klug, T.; Bartram, J. Seasonality, Water Use and Community Management of Water Systems in Rural Settings: Qualitative Evidence from Ghana, Kenya, and Zambia. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628–629, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonj, C.; Fleming, L.; Cronk, R.; Godfrey, S.; Ambelu, A.; Bevan, J.; Sozzi, E.; Bartram, J.; Anthonj, C.; Fleming, L.; et al. Improving Monitoring and Water Point Functionality in Rural Ethiopia. Water 2018, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.; MacDonald, A.; Coulter, L.; Calow, R.C. Household Water Use, Poverty and Seasonality: Wealth Effects, Labour Constraints, and Minimal Consumption in Ethiopia. Water Resour. Rural Dev. 2014, 3, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Hope, R. A Multi-Decadal and Social-Ecological Systems Analysis of Community Waterpoint Payment Behaviours in Rural Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, T.; Willetts, J.; Lane, M.; Thomson, P.; Katuva, J.; Hope, R. Risk Factors Associated with Rural Water Supply Failure: A 30-Year Retrospective Study of Handpumps on the South Coast of Kenya. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, C.; Franceys, R.; Batchelor, C.; Mcintyre, P.; Klutse, A.; Komives, K.; Moriarty, P.; Naafs, A.; Nyarko, K.; Pezon, C.; et al. Life-Cycle Costs Approach Glossary and Cost Components; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Franceys, R.; Pezon, C. Services Are Forever: The Importance of Capital Maintenance (CapManEx) in Ensuring Sustainable WASH Services Briefing Note 1b; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, T.; Uguru, O.P.; Jafry, T.; Chinsinga, B.; Mvula, P.; Chunga, J.; Zimba, L.M.; Mwape, M.; Nyundo, L.; Mwiinga, B.; et al. The Role of Social Actors in Water Access in Sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from Malawi and Zambia. Water Resour. Rural Dev. 2016, 8, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kativhu, T.; Mazvimavi, D.; Tevera, D.; Nhapi, I. Implementation of Community Based Management (CBM) in Zimbabwe: The Dichotomy of Theory and Practice and Its Influence on Sustainability of Rural Water Supply Systems. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2018, 106, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcintyre, P.; Casella, D.; Fonseca, C.; Burr, P. Supporting Water Sanitation and Hygiene Services for Life Priceless! Uncovering the Real Costs of Water and Sanitation; IRC: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivett, M.O.; Halcrow, A.W.; Schmalfuss, J.; Stark, J.A.; Truslove, J.P.; Kumwenda, S.; Harawa, K.A.; Nhlema, M.; Songola, C.; Wanangwa, G.J.; et al. Local Scale Water-Food Nexus: Use of Borehole-Garden Permaculture to Realise the Full Potential of Rural Water Supplies in Malawi. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 209, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittington, D.; Davis, J.; Prokopy, L.; Komives, K.; Thorsten, R.; Lukacs, H.; Bakalian, A.; Wakeman, W. How Well Is the Demand-Driven, Community Management Model for Rural Water Supply Systems Doing? Evidence from Bolivia, Peru and Ghana. Water Policy 2009, 11, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.B.; Shields, K.F.; Chan, T.U.; Christenson, E.; Cronk, R.; Leker, H.; Samani, D.; Apoya, P.; Lutz, A.; Bartram, J. Understanding Handpump Sustainability: Determinants of Rural Water Source Functionality in the Greater Afram Plains Region of Ghana. Water Resour. Res. 2015, 51, 8431–8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, S.; Rojas, J.; Tamayo, P. The Impact of Support to Community-Based Rural Water Service Providers: Evidence from Colombia. Water Altern. 2013, 6, 384–404. [Google Scholar]

- Oates, N.; Mwathunga, E. A Political Economy Analysis of Malawi’s Rural Water Supply Sector; ODI: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley, L.; MacAllister, D.J.; Bonsor, H.; Mwathunga, E.; Banda, S.; Katusiime, F.; Tadesse, Y.; Cleaver, F.; MacDonald, A. Evidence, Ideology, and the Policy of Community Management in Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 085013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etongo, D.; Fagan, G.; Kabonesa, C.; Asaba, B.R.; Etongo, D.; Fagan, G.H.; Kabonesa, C.; Asaba, B.R. Community-Managed Water Supply Systems in Rural Uganda: The Role of Participation and Capacity Development. Water 2018, 10, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, P.A.; Reed, R.A. Sustainable Supply Chains for Rural Water Supplies in Africa. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2006, 159, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WaterAid. Sustainability Framework; WaterAid: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, P.A. Cost Determination and Sustainable Financing for Rural Water Service in Sub-Saharan Africa. Water Policy 2007, 9, 373–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, S.F.; Hope, R. Examining the Economics of Affordability through Water Diaries in Coastal Bangladesh. Water Econ. Policy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WAREG. Affordability in European Water; WAREG: Milan, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

| Service Provider | Service Provider Variable | ||||||

| w/ Tariff | w/o Tariff | ||||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Established 1 | No | 1162 | 5.38 | - | - | 1162 | 100 |

| Yes | 20,456 | 94.62 | 16,796 | 82.11 | 3657 | 17.88 | |

| Total | 21,618 | 100 | 16,796 | 77.70 | 4819 | 22.30 | |

| Where Service Provider Present (n = 20,438) 1 | Service Provider Variable | ||||||

| w/ Tariff | w/o Tariff | ||||||

| Variable | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Single Service Provider | WPC | 16,250 | 79.51 | 13,644 | 83.96 | 2604 | 16.02 |

| Area Mechanic | 1060 | 5.19 | 888 | 83.77 | 171 | 16.13 | |

| Community Members | 410 | 2.01 | 270 | 65.85 | 140 | 34.15 | |

| Institution | 430 | 2.10 | 143 | 33.26 | 287 | 66.74 | |

| Other 2 | 177 | 0.87 | 92 | 51.98 | 85 | 48.02 | |

| Total | 18,327 | 89.67 | 15,037 | 82.05 | 3287 | 17.94 | |

| Multiple Service Providers | =2 | 1969 3 | 93.27 | 1638 | 83.19 | 331 | 16.81 |

| =3 | 140 | 7.11 | 107 | 76.43 | 33 | 23.57 | |

| =4 | 2 | 1.43 | 2 | 100.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Total | 2111 4 | 10.33 | 1747 | 82.76 | 364 | 17.24 | |

| No. of Users 1 | ||||||

| Variable | Total | ≤300 | >300 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total, n 1 | 16,670 | 100 | 8699 | 52.18 | 7971 | 47.82 |

| Single Frequency | 15,938 | 95.61 | 8342 | 52.34 | 7596 | 47.66 |

| Multiple Frequencies | 732 | 4.39 | 357 | 48.77 | 375 | 51.23 |

| Tariff (MWK) 1 | ||||||

| Variable | Total | ≤500 | >500 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total, n 1 | 16,761 | 100 | 15,674 | 93.51 | 1087 | 6.49 |

| Single Frequency | 16,023 | 95.60 | 14,989 | 93.55 | 1034 | 6.45 |

| Multiple Frequencies | 738 | 4.40 | 685 | 92.82 | 53 | 7.18 |

| No. of Users 1 | ||||||

| Variable | Total | ≤300 | >300 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total, n 1 | 16,676 | 100 | 8696 | 52.15 | 7980 | 47.85 |

| Single Consideration | 12,192 | 73.11 | 6289 | 51.58 | 5903 | 48.42 |

| Multiple Considerations 2 | 4484 | 26.89 | 2407 | 53.68 | 2077 | 46.32 |

| Tariff (MWK) 1 | ||||||

| Variable | Total | ≤500 | >500 | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Total, n 1 | 16,737 | 100 | 15,651 | 93.51 | 1086 | 6.49 |

| Single Considerations | 12,242 | 73.14 | 11,473 | 93.72 | 769 | 6.28 |

| Multiple Considerations 2 | 4495 | 26.86 | 4178 | 92.95 | 317 | 7.05 |

| Explanatory Variables | Affordability | O&M | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of Total | n | % Considering Affordability | n | % Considering O&M | |

| Service Provider | ||||||

| WPC | 11,853 | 81.95 | 6189 | 52.21 | 8085 | 68.21 |

| Area Mechanic | 757 | 5.23 | 478 | 63.14 | 347 | 45.84 |

| Community Members | 217 | 1.50 | 115 | 53.00 | 134 | 61.75 |

| Institution | 86 | 0.59 | 48 | 55.81 | 55 | 63.95 |

| Other | 79 | 0.55 | 51 | 64.56 | 48 | 60.76 |

| Multiple SP | 1471 | 10.17 | 1055 | 71.72 | 1138 | 77.36 |

| Frequency of Tariff | ||||||

| Per Month | 7327 | 50.66 | 4247 | 57.96 | 4711 | 64.30 |

| Per Year | 2948 | 20.38 | 1497 | 50.78 | 2192 | 74.36 |

| When Required for Repairs | 3329 | 23.02 | 1695 | 50.92 | 2334 | 70.11 |

| Per 2 Months | 317 | 2.19 | 183 | 57.73 | 200 | 63.09 |

| Per Quarter | 542 | 3.75 | 314 | 57.93 | 370 | 68.27 |

| Tariff Amount | ||||||

| Tariff (Annual) | 14,463 | 100 | 7936 | 54.87 | 9807 | 67.81 |

| Users | ||||||

| ≤300 | 8169 | 56.48 | 4709 | 57.64 | 5371 | 65.75 |

| >300 | 6294 | 43.52 | 3227 | 51.27 | 4436 | 70.48 |

| Preventative Maintenance | ||||||

| No | 2689 | 18.59 | 1373 | 51.06 | 1725 | 64.15 |

| Yes | 11,774 | 81.41 | 6563 | 55.74 | 8082 | 68.64 |

| Spare Parts Kept on Site | ||||||

| No | 4648 | 32.14 | 2609 | 56.13 | 2992 | 64.37 |

| Yes | 9815 | 67.86 | 5327 | 54.27 | 6815 | 69.43 |

| Functionality | ||||||

| Functional | 11,003 | 76.08 | 5876 | 53.40 | 7404 | 67.29 |

| Partially Functional | 2964 | 20.49 | 1782 | 60.12 | 2066 | 69.70 |

| Non-Functional | 496 | 3.43 | 278 | 56.05 | 337 | 67.94 |

| Age | ||||||

| Age (Years) | 14,463 | 100 | 7936 | 54.87 | 9807 | 67.81 |

| Region | ||||||

| Southern | 7762 | 53.67 | 4404 | 56.74 | 5429 | 69.94 |

| Central | 6594 | 45.59 | 3481 | 52.79 | 4308 | 65.33 |

| Northern | 107 | 0.74 | 51 | 47.66 | 70 | 65.42 |

| Explanatory Variables | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | OR | (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | |

| Service Provider | ||||||

| WPC | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Area Mechanic | 1.568 | (1.347–1.825) | <0.001 | 1.629 | (1.394–1.903) | <0.001 |

| Community Members | 1.032 | (0.788–1.350) | 0.820 | 1.105 | (0.840–1.452) | 0.476 |

| Institution | 1.156 | (0.754–1.772) | 0.506 | 1.329 | (0.862–2.047) | 0.198 |

| Other | 1.667 | (1.050–2.647) | 0.030 | 1.658 | (1.039–2.646) | 0.034 |

| Multiple SP | 2.321 | (2.060–2.614) | <0.001 | 2.397 | (2.121–2.709) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of Tariff 2 | ||||||

| Per Month | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Per Year | 0.748 | (0.687–0.815) | <0.001 | 0.615 | (0.555–0.682) | <0.001 |

| When Required for Repairs | 0.752 | (0.693–0.817) | <0.001 | 0.598 | (0.537–0.666) | <0.001 |

| Per 2 Months | 0.990 | (0.789–1.244) | 0.934 | 0.922 | (0.731–1.163) | 0.492 |

| Per Quarter | 0.999 | (0.837–1.192) | 0.989 | 0.890 | (0.742–1.068) | 0.209 |

| Tariff Amount | ||||||

| MWK (Annual) 3 | 1.000 | (1.000–1.000) | 0.067 | 1.000 | (1.000–1.000) | <0.001 |

| Users | ||||||

| ≤300 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | |

| >300 | 0.773 | (0.724–0.826) | <0.001 | 0.764 | (0.714–0.818) | <0.001 |

| Preventative Maintenance | ||||||

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1.207 | (1.110–1.313) | <0.001 | 1.168 | (1.071–1.273) | <0.001 |

| Spare Parts Kept on Site | ||||||

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 0.928 | (0.865–0.995) | 0.036 | 1.029 | (0.956–1.109) | 0.445 |

| Functionality | ||||||

| Functional | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Partially Functional | 1.315 | (1.211–1.429) | <0.001 | 1.413 | (1.297–1.539) | <0.001 |

| Non-Functional | 1.113 | (0.928–1.334) | 0.248 | 1.193 | (0.991–1.436) | 0.063 |

| Age | ||||||

| Age (Years) | 0.996 | (0.991–1.002) | 0.219 | 0.992 | (0.987–0.998) | 0.209 |

| Region | ||||||

| Southern | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Central | 0.853 | (0.798–0.911) | <0.001 | 1.070 | (0.994–1.151) | 0.072 |

| Northern | 0.694 | (0.474–1.017) | 0.061 | 0.761 | (0.513–1.128) | 0.174 |

| Explanatory Variables | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | OR | (95% CI) | p-Value 1 | |

| Service Provider | ||||||

| WPC | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Area Mechanic | 0.394 | (0.340–0.457) | <0.001 | 0.366 | (0.313–0.427) | <0.001 |

| Community Members | 0.752 | (0.571–0.992) | 0.044 | 0.738 | (0.553–0.986) | 0.040 |

| Institution | 0.827 | (0.532–1.286) | 0.399 | 0.724 | (0.457–1.147) | 0.169 |

| Other | 0.722 | (0.459–1.135) | 0.158 | 0.738 | (0.455–1.195) | 0.216 |

| Multiple SP | 1.593 | (1.401–1.810) | <0.001 | 1.531 | (1.339–1.751) | <0.001 |

| Frequency of Tariff 2 | ||||||

| Per Month | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Per Year | 1.610 | (1.463–1.771) | <0.001 | 2.397 | (2.127–2.702) | <0.001 |

| When Required for Repairs | 1.303 | (1.193–1.423) | <0.001 | 2.411 | (2.131–2.727) | <0.001 |

| Per 2 Months | 0.949 | (0.752–1.198) | 0.661 | 1.204 | (0.934–1.551) | 0.152 |

| Per Quarter | 1.195 | (0.991–1.440) | 0.063 | 1.567 | (1.282–1.916) | <0.001 |

| Tariff Amount | ||||||

| MWK (Annual) 3 | 1.000 | (1.000–1.000) | 0.010 | 1.000 | (1.000–1.000) | <0.001 |

| Users | ||||||

| ≤300 | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| >300 | 1.244 | (1.159–1.335) | <0.001 | 1.241 | (1.151–1.338) | <0.001 |

| Preventative Maintenance | ||||||

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1.223 | (1.120–1.336) | <0.001 | 1.160 | (1.056–1.274) | 0.002 |

| Spare Parts Kept on Site | ||||||

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1.257 | (1.168–1.354) | <0.001 | 1.301 | (1.200–1.410) | <0.001 |

| Functionality | ||||||

| Functional | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Partially Functional | 1.118 | (1.024–1.221) | 0.013 | 1.043 | (0.949–1.147) | 0.378 |

| Non-Functional | 1.030 | (0.850–1.249) | 0.762 | 1.108 | (0.904–1.358) | 0.324 |

| Age | ||||||

| Age (Years) | 0.999 | (0.993–1.005) | 0.798 | 0.998 | (0.992–1.005) | 0.645 |

| Region | ||||||

| Southern | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Central | 0.810 | (0.755–0.869) | <0.001 | 0.598 | (0.551–0.649) | <0.001 |

| Northern | 0.813 | (0.544–1.214) | 0.312 | 0.921 | (0.246–3.448) | 0.903 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truslove, J.P.; Coulson, A.B.; Nhlema, M.; Mbalame, E.; Kalin, R.M. Reflecting SDG 6.1 in Rural Water Supply Tariffs: Considering ‘Affordability’ Versus ‘Operations and Maintenance Costs’ in Malawi. Sustainability 2020, 12, 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020744

Truslove JP, Coulson AB, Nhlema M, Mbalame E, Kalin RM. Reflecting SDG 6.1 in Rural Water Supply Tariffs: Considering ‘Affordability’ Versus ‘Operations and Maintenance Costs’ in Malawi. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020744

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruslove, Jonathan P., Andrea B. Coulson, Muthi Nhlema, Emma Mbalame, and Robert M. Kalin. 2020. "Reflecting SDG 6.1 in Rural Water Supply Tariffs: Considering ‘Affordability’ Versus ‘Operations and Maintenance Costs’ in Malawi" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020744

APA StyleTruslove, J. P., Coulson, A. B., Nhlema, M., Mbalame, E., & Kalin, R. M. (2020). Reflecting SDG 6.1 in Rural Water Supply Tariffs: Considering ‘Affordability’ Versus ‘Operations and Maintenance Costs’ in Malawi. Sustainability, 12(2), 744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020744