An Assessment and Spatial Modelling of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain (2015–2030)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. An Introduction of LUISA Territorial Modelling Platform

2.2. Modelling Agricultural Land Abandonment in LUISA Platform

2.2.1. Land-Use Map Projections: Agricultural Land and Land-Use Competition

2.2.2. Biophysical Limitations for Generic Agricultural activities

2.2.3. Agroeconomics and Farm Structural Factors

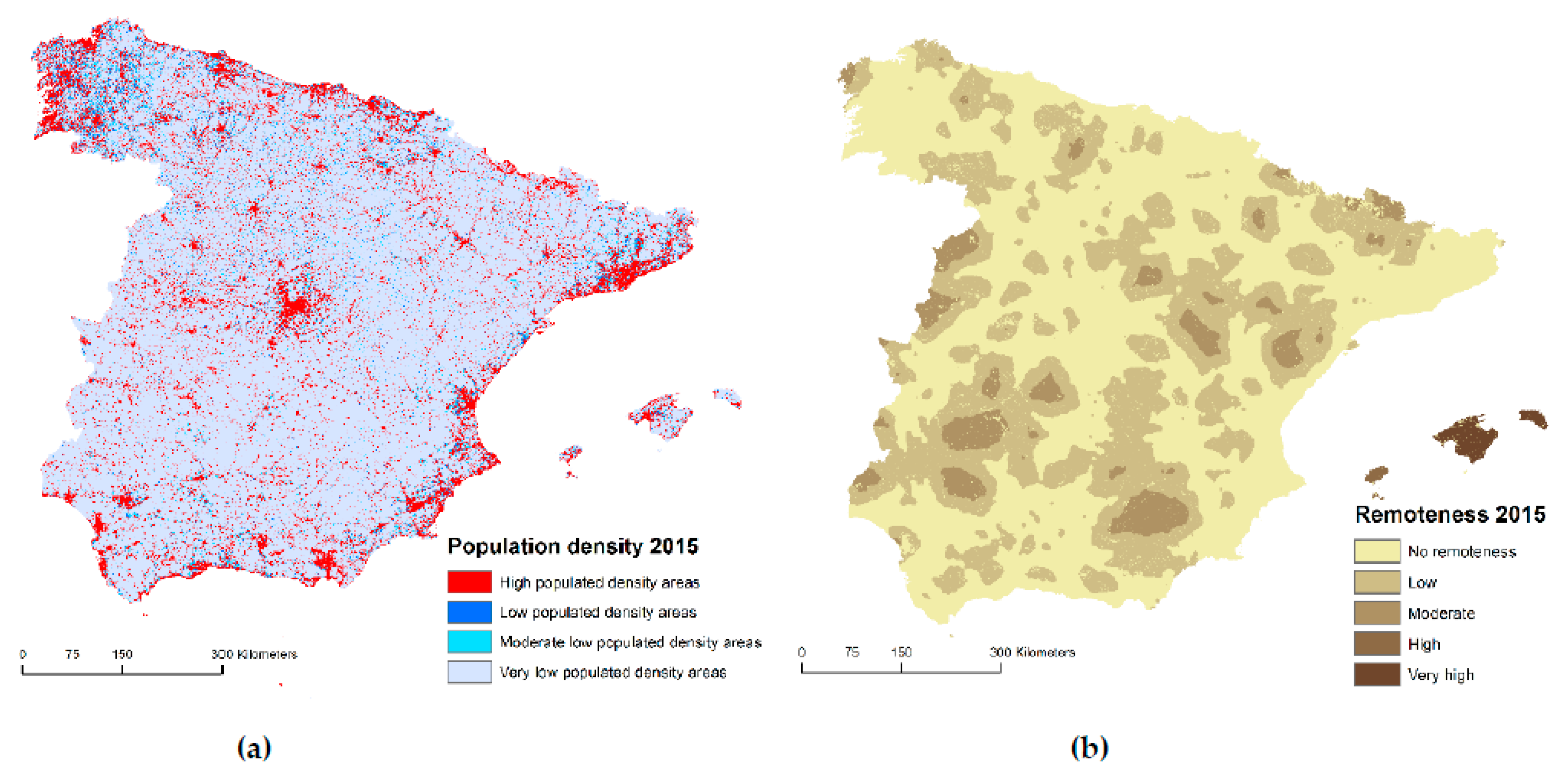

2.2.4. Demographic and Geographic Regional Factors

2.3. Agricultural Land Abandonment on Mountainous and Natural Areas

3. Results

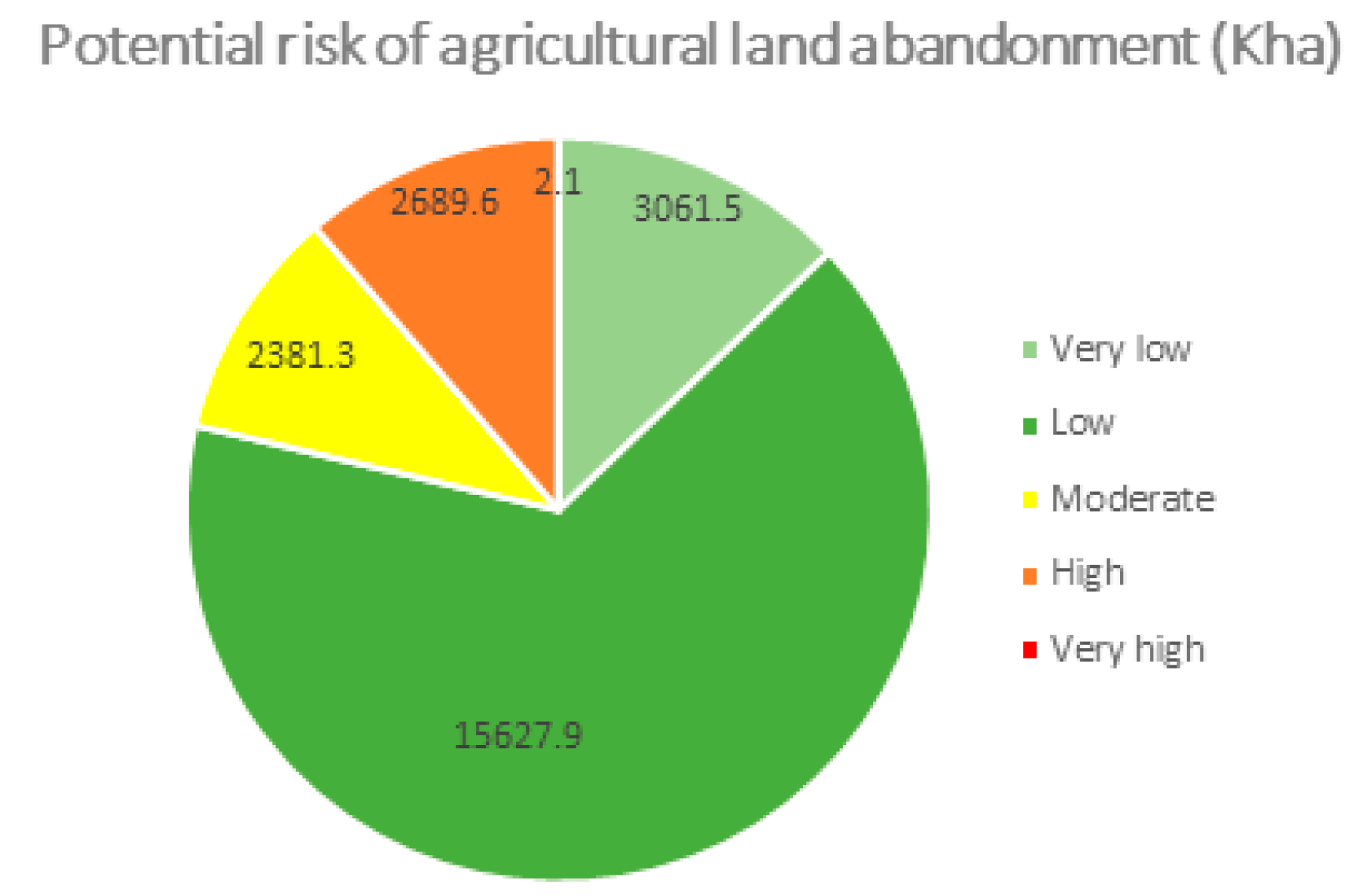

3.1. Potential Risk Map of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain

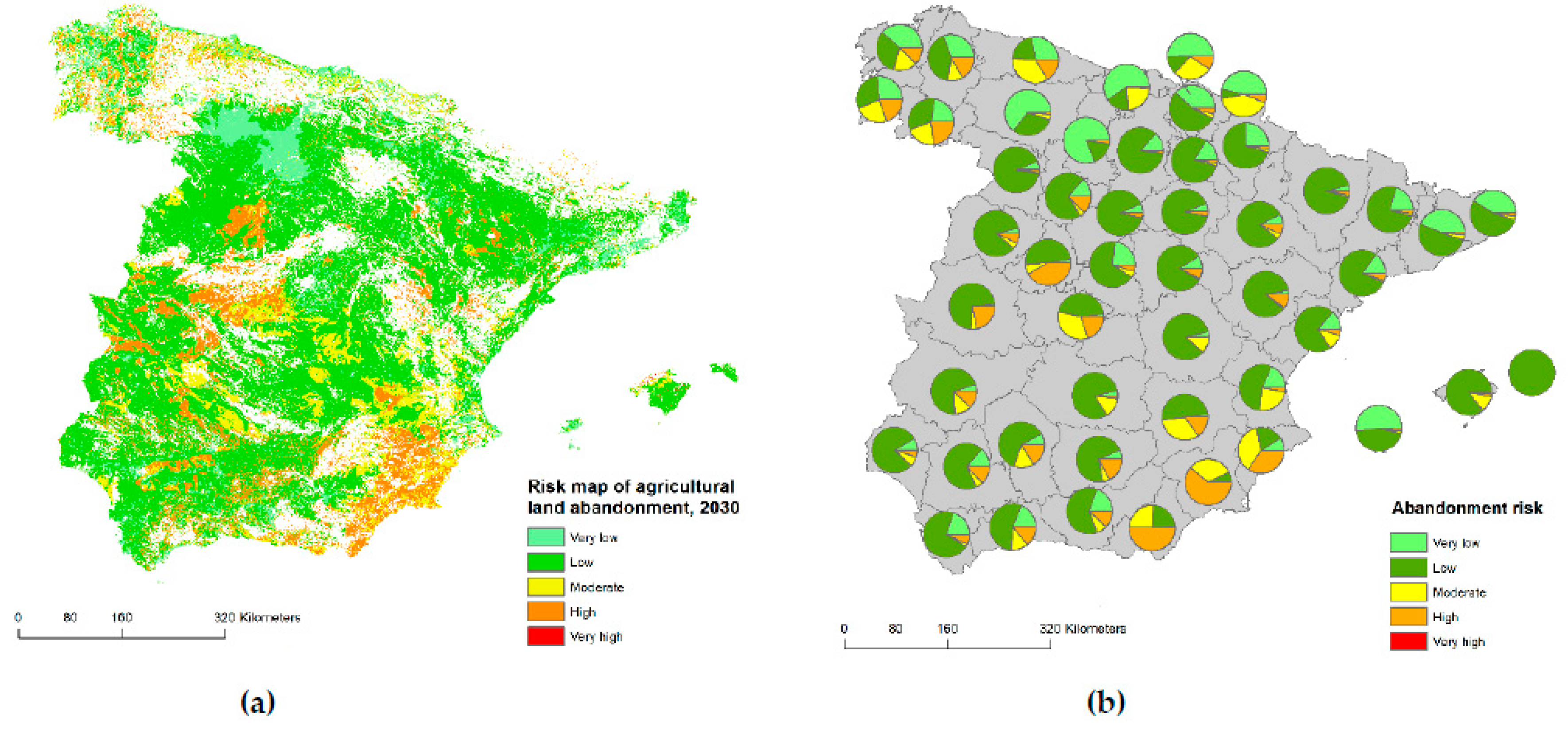

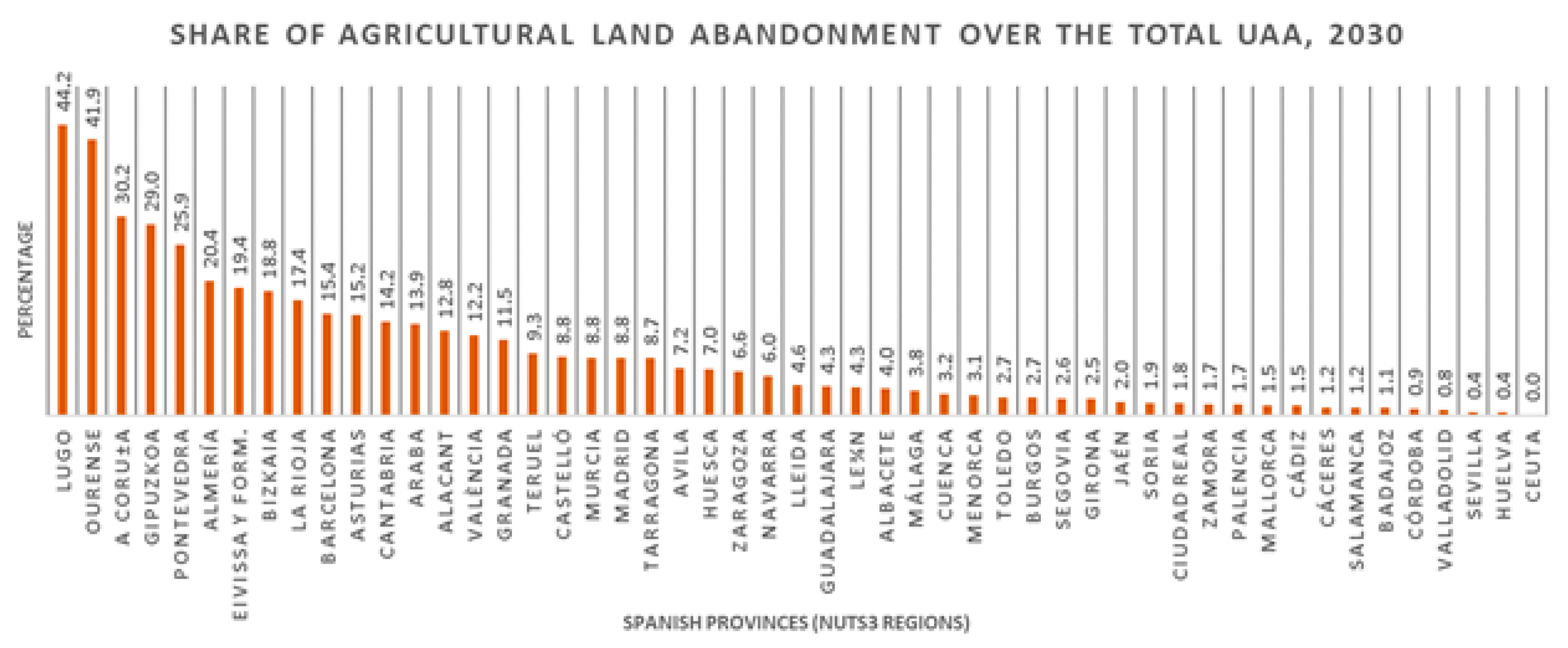

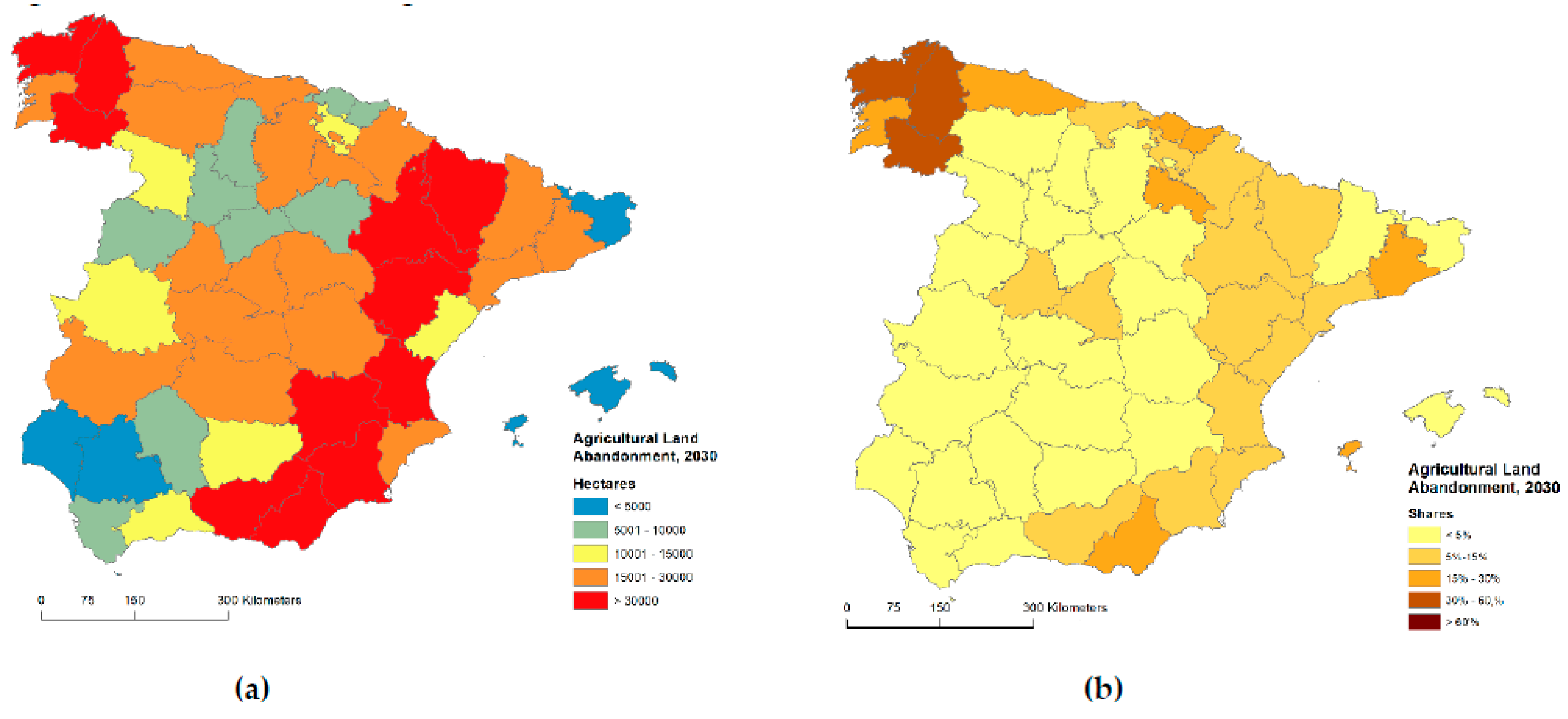

3.2. Evolution of the Land Abandonment in Spain at Regional Scale, 2015–2030

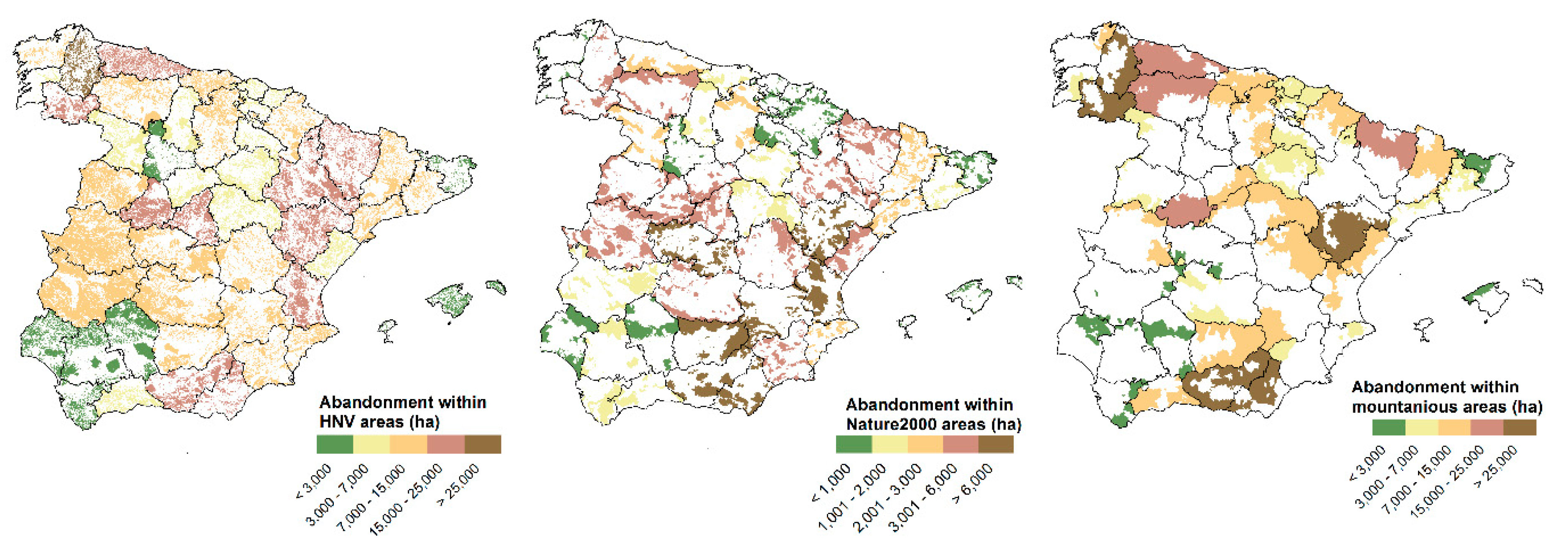

3.3. Agricultural Land Abandonment in Natural and Mountainous Areas

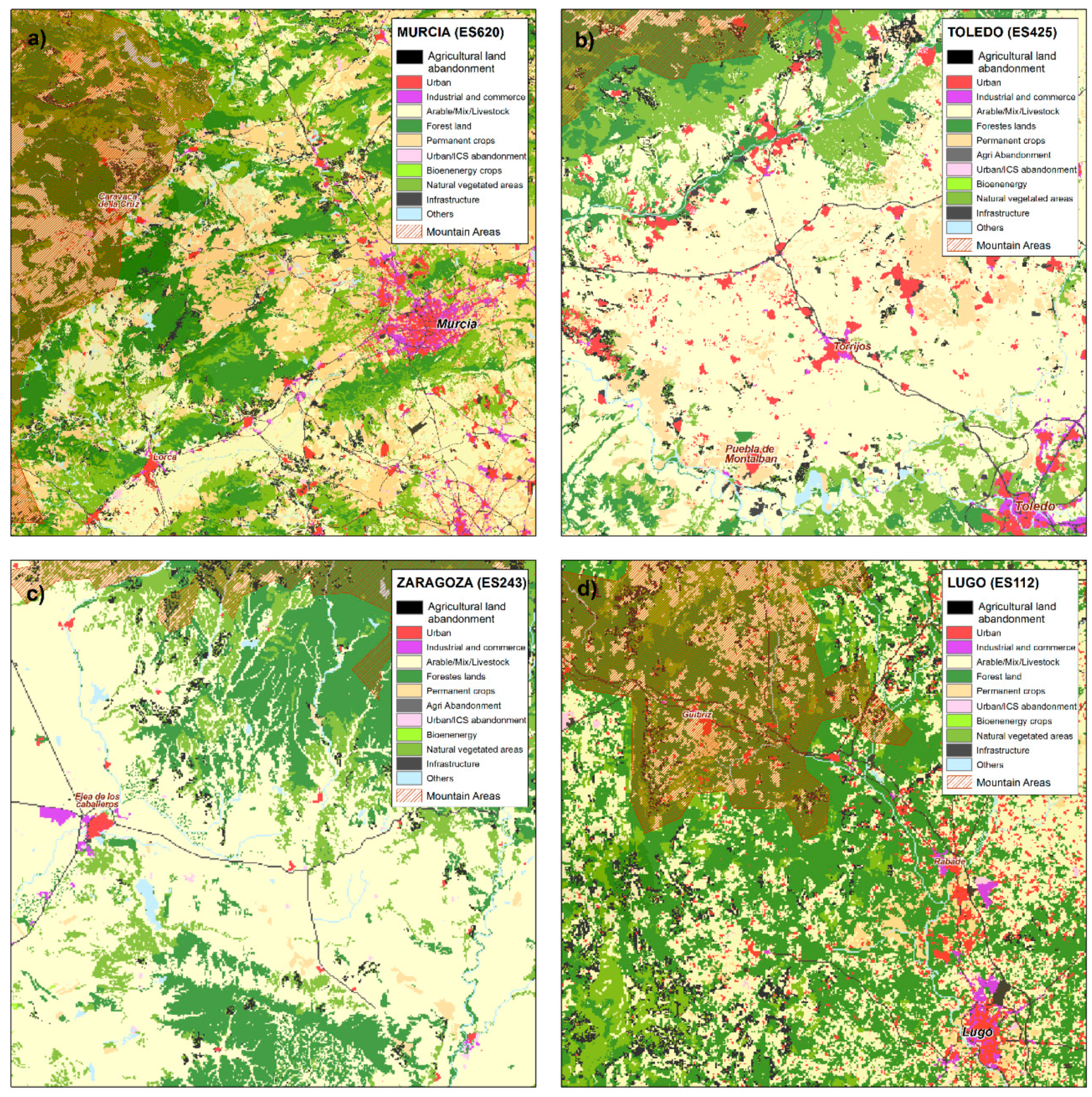

3.4. Agricultural Land Abandonment at Local Scale (Spain)

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| NUTS3 Region, Abandonment Share | Abandonment Areas from [6] and Shares | Municipalities (LAU2) in LUISA and Shares |

|---|---|---|

| Asturias (ES120), 15% | Abandonment areas numbered as 12, 13 and 22 with shares between 40% and 80% | Abandonment areas correspond to the municipalities of: Allande, Teverga, Aller, Camaleño, Polaciones, Valdeolea and San Roque de Riomiera ranging from 38% to 53% shares |

| Madrid (ES300), 9% | Abandonment areas numbered as 14 and 15 with shares between 75% and 89% | Abandonment areas correspond to the municipalities of: Puentes Viejas, Navarredonda y San Mamés, Lozoyuela, Manzanares el Real, San Ildefonso, Narrillos del Álamo, Orihuela, Medinilla, La Carrera and Piedrahita ranging from 42% to 81% shares |

| Lleida (ES513), 4.5% | Abandonment areas numbered as 18 and 21 with shares between 40% and 71% | Abandonment areas correspond to the municipalities of: Torre de Cabdella, Sort, Les Valls d’Aguilar, Prullans, La Vansa i Fórnols, El Pont de Suert, Valderrobres, Monroyo, Castellote and Villarluengo ranging from 31% to 85% shares |

| Rioja (ES230), 17.5% | Abandonment areas numbered as 19 and 20 with shares between 42% and 99% | Abandonment areas correspond to the municipalities of: San Asensio, Cenicero, Sotés, Haro, Tarazona, Borja, Ainzón, Fuendejalón and Morata de Jalón ranging from 33% to 81% shares |

| Málaga (ES617), 10% | Abandonment area numbered as 16 and 23 with shares between 36% and 70% | Abandonment areas correspond to the municipalities of: Villaluenga del Rosario, Ronda, Alpujarra de la Sierra, Nevada, Albondón, Torvizcón, Fiñana, Fondón, Felix, Lubrín, Macael, Oria and Chirivel ranging from 45% to 74% shares |

References

- Gellrich, M.; Zimmermann, N.E. Investigating the regional-scale pattern of agricultural land abandonment in the Swiss mountains: A spatial statistical modelling approach. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 79, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Sarría, F.; Martínez-Hernández, C.; Romero-Díaz, A.; Cánovas-García, F.; Gomariz-Castillo, F. Main environmental features leading to recent land abandonment in Murcia region (southeast Spain). Land Degrad. Dev. 2016, 27, 654–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcucci, A.; Maiorano, L.; Boitani, L. Changes in land-use/land-cover patterns in Italy and their implications for biodiversity conservation. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyatos, R.; Latron, J.; Llorens, P. Land use and land cover change after agricultural abandonment. Mt. Res. Dev. 2003, 23, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, M.; Le Page, C.; Cohen, M. A Step-By-Step Approach to Building Land Management Scenarios Based on Multiple Viewpoints on Multi-Agent System Simulations Ecology and Society. Available online: http://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/6/2/2.html (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Lasanta. T.; Arnáez, J.; Pascual, N.; Ruiz-Flañ0, R.; Errea, M.P.; Lana-Renault, N. Space-time process and drivers of land abandonment in Europe. Catena 2016, 149, 810–823. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.R.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, N.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe Environmental consequences end policy response. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbelle-Rico, E.; Crecente-Maseda, R.; Santé-Riveira, I. Multi-scale assessment and spatial modelling of agricultural land abandonment in a European peripheral region: Galicia (Spain), 1956–2004. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Mandel, M.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Feher, A.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J. An assessment of the causes and consequences of agricultural land abandonment in Europe. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 24, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointereau, P.; Coulon, F.; Girard, P.; Lambotte, M.; Stuczynski, T.; Sanchez Ortega, V.; Del Rio, A. Analysis of Farmland Abandonment and the Extent and Location of Agricultural Areas that Are Actually Abandoned or Are in Risk to Be Abandoned; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2008; JRC46185; ISSN 1018-5593. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, C.C.E.; Cammeraat, E.L.H.; de Vente, J.; Boix-Fayos, C. The evolution of soil conservation policies targeting land abandonment and soil erosion in spain: A review. Land Use Policy 2019, 83, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.; Martins, A.; Nicolau, J.M.; Schulz, J.J. Abandonment of agricultural land: An overview of drivers and consequences. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2007, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terres, J.M.; Nisini Scacchiafichi, L.; Wania, A.; Ambar, M.; Anguiano, E.; Buckwell, A.; Coppola, A.; Gocht, A.; Nordström Källström, A.; Pointereau, P.; et al. Farmland abandonment in Europe: Identification of drivers and indicators, and development of a composite indicator of risk. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prishchepov, A.V.; Müller, D.; Dubinin, M.; Baumann, M.; Radeloff, V.C. Determinants of agricultural land abandonment in post-Soviet European Russia. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levers, C.; Schneider, M.; Prishchepov, A.V.; Estel, S.; Kuemmerle, T. Spatial variation in determinants of agricultural land abandonment in Europe. Sci. Total. Environ. 2018, 644, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keenleyside, C.; Tucker, G.M. Farmland Abandonment in the EU: An Assessment of Trends and Prospects; Report prepared for WWF; Institute for European Environmental Policy: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lasanta, T.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Cuadrat, J.M. Mountain Mediterranean landscape evolution caused by abandonment of traditional primary activities: A study of the Spanish Central Pyrenees. Appl. Geogr. 2005, 25, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Martínez-Hernández, C.; Iserloh, T.; Cerdà, A. Contrasted impact of land abandonment on soil erosion in Mediterranean agriculture fields. Pedosphere 2018, 28, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdà, A.; Rodrigo-Comino, J.; Novara, A.; Brevik, E.C.; Vaez, R.V.; Pulido, M.; Giménez-Morera, A.; Keesstra, S.D. Long-term impact of rainfed agricultural land abandonment on soil erosion in the Western Mediterranean basin. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2018, 42, 202–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lasanta, T.; Errea, M.P.; Ortigosa, L. Land abandonment, landscape evolution, and soil erosion in a Spanish Mediterranean mountain region: The case of Camero Viejo. Land Degrad. Dev. 2011, 22, 537–550. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Díaz, A.; Ruiz-Sinoga, J.D.; Robledano-Aymerich, F.; Brevik, E.C.; Cerdà, A. Ecosystem responses to land abandonment in Western Mediterranean Mountains. Catena 2017, 149, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Abandonment, Biodiversity and the CAP. In Proceedings of the Outcomes of an International Seminar, Sigulda, Latvia, 7–8 October 2004.

- Elbersen, B.; Beaufoy, G.; Jones, G.; Noij, G.-J.; Doorn, A.; Breman, B.; Hazeu, G. Aspects of data on diverse relationships between agriculture and the environment. In Report for DG-Environment; Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ECORYS. SEGIRA—Study on employment, growth and innovation in rural areas. In Main Report; ECORYS: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, M.; Kuemmerle, T.; Elbakidzed, M.; Ozdogan, M.; Radeloff, V.; . Keuler, N.; Prishchepov, A.; Kruhlov, I.; Hostert, P. Patterns and drivers of post-socialist farmland abandonment in Western Ukraine. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazúr, R.; Lieskovský, J.; Feranec, J.; Otahel, J. Spatial determinants of abandonment of large-scale arable lands and managed grasslands in Slovakia during the periods of post-socialist transition and European Union accession. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 54, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbelle-Rico, E.; Crecente-Maseda, R. Evaluating IRENA indicator “Risk of Farmland Abandonment” on a low spatial scale level: The case of Galicia (Spain). Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbelle-Rico, E.; Crecente-Maseda, R. Land abandonment: Concept and consequences. Revista Galega de Economía 2008, 17, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ruiz, J.M. The effects of land uses on soil erosion in Spain: A review. Catena 2010, 81, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat (2016)—EUROPOP2013, Convergence Scenario, National Level. Available online: http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_SDDS/EN/proj_10c_esms.htm (accessed on 15 January 2016).

- Britz, W.; Witzke, H.P. CAPRI Model Documentation 2012. Institute for Food and Resource Economics; University Bonn: Bonn, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. General Equilibrium Model for the Economy-Energy–Environment (GEM-E3). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/gem-e3/model (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre. Dynamic Spatial General Equilibrium Model for EU Regions and Sectors (RHOMOLO). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/rhomolo (accessed on 8 February 2018).

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre. JRC-EU-Times Model Assessing Long Term Role Energy Technologies. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/scientific-tool/jrc-eu-times-model-assessing-long-term-role-energy-technologies (accessed on 25 January 2016).

- Baranzelli, C.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Batista e Silva, F.; Perpiña Castillo, C.; Barbosa, A.; Arevalo Torres, J.; Lavalle, C. The reference scenario in the LUISA platform—Updated configuration 2014 towards a common baseline scenario for EC impact assessment procedures. Publ. Off. Eur. Union Luxemb. 2014, 10, 85104. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Diogo, V.; Perpiña Castillo, C.; Baranzelli, C.; Batista e Silva, F.; Rosina, K.; Kavalov, B.; Lavalle, C. The LUISA Territorial Reference Scenario: A Technical Description; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista e Silva, F.; Lavalle, C.; Koomen, E. A procedure to obtain a refined European land use/cover map. J. Land Use Sci. 2013, 8, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Modeling the Choice of Residential Location. Transp. Res. Rec. 1978, 672, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hilferink, M.; Rietveld, P. Land use scanner: An integrated GIS based model for long term projections of land use in urban and rural areas. J. Geogr. Syst. 1999, 1, 155–177. [Google Scholar]

- Koomen, E.; Diogo, V.; Dekkers, J.; Rietveld, P. A utility-based suitability framework for integrated local-scale land-use modelling. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 50, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña Castillo, C.; Kavalov, B.; Ribeiro Barranco, R.; Diogo, V.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Batista e Silva, F.; Baranzelli, C.; Lavalle, C. Territorial Facts and Trends in the EU Rural Areas within 2015–2030; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; JRC114016; ISBN 978-92-79-98121-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavalle, C.; Pontarollo, N.; Batista, E.; Silva, F.; Baranzelli, C.; Jacobs, C.; Kavalov, B.; Kompil, M.; Perpiña Castillo, C.; Vizcaino, M.; et al. European Territorial Trends—Facts and Prospects for Cities and Regions; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017; JRC107391; ISBN 978-92-79-73428-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña Castillo, C.; Lavalle, C.; Baranzelli, C.; Mubareka, S. Modelling the spatial allocation of second-generation feedstock (lignocellulosic crops) in Europe. International J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 29, 1807–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompil, M.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Dijkstra, L.; Lavalle, C. Mapping access to generic services in Europe: A market-potential based approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 4, 101372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Batista e Silva, F.; Lavalle, C.; Baranzelli, C.; Barbosa, A.; Perpiña Castillo, C. Accessibility and territorial cohesion in a case of transport infrastructure improvements with changing population distributions. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2016, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre. Available online: https://urban.jrc.ec.europa.eu/#/en (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/knowledge4policy/online-resource/territorial-dashboard_en (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- European Commission, Eurostat. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/reference-data/administrative-units-statistical-units/nuts (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre. LUISA Collection, Data Catalogue. Available online: https://data.jrc.ec.europa.eu/collection/luisa (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre. LUISA Territorial Modelling Platform. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/luisa (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- IIASA/FAO. Global Agro-Ecological Zones—GAEZ Portal. 2013. Available online: http://www.gaez.iiasa.ac.at/ (accessed on 7 April 2017).

- Hiederer, R. Processing a Soil Organic Carbon C-Stock Baseline under Cropland and Grazing Land Management. In EUR 28158 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/IIASA/ISRIC/ISSCAS/JRC. Harmonized World Soil Database (Version 1.2); FAO: Rome, Italy; IIASA: Laxenburg, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre; European Soil data Centre (ESDAC); Sinfo (Soil data for the MARS). Data for the Soil Information System for the MARS Crop Yield Forecasting System (SINFO). Available online: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/sinfo-soil-data-mars-information (accessed on 20 May 2017).

- European Commission–Joint Research Centre; European Soil data Centre (ESDAC); European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Spatial Data Version 1.1. Available online: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/european-food-safety-authority-efsa-data-persam-software-tool (accessed on 5 July 2017).

- NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration). Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM). Available online: http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/srtm/ (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- European Commission, Eurostat. Farm structure surveys (FSS)-Structure of agricultural holdings. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Main_Page (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- European Commission, Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN). Special request of microdata to DG Agriculture and rural Development, Farm Economics Unit. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/ (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Dijkstra, L.; Poelman, H. A Harmonised Definition of Cities and Rural Areas: The New Degree of Urbanisation; Regional Policy Working Papers; European Commission, Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, Å.; Jones, R.J.; Nachtergaele, F.; Rossiter, D.G.; Terres, J.M.; Van Orshoven, J.; Van Velthuizen, H.; Böttcher, K.; Haastrup, P.; Le Bas, C. Common criteria for the redefinition of intermediate less favoured areas in the European Union. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council Directive 95/212/EC of 29 May 1995 concerning the Community list of less-favoured farming areas within the meaning of Directive 75/268/EEC.

- EEA—European Environment Agency. High Nature Value (HNV) Farmland. European Environment Agency, Copenhagen, Denmark. 2015. Available online: http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/high-nature-value-farmland (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- EEA—European Environment Agency. Natura 2000 Data—the European Network of Protected Sites. European Environment Agency, Copenhagen, Denmark. 2017. Available online: http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/natura-8 (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Walford, N. Agricultural adjustment: Adoption of an adaptation to policy reform by large-scale commercial farmers. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, A.; Jansson, T.; Verburg, P.H.; Revoredo-Giha, C.; Britz, W.; Gocht, A.; McCracken, D. Policy reform and agricultural land abandonment in the EU. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M.M.; Govers, G.; van Doorn, A.; Quetier, F.; Chouvardas, D.; Rounsevell, M. The response of soil erosion and sediment export to land-use change in four areas of Europe: The importance of landscape pattern. Geomorphology 2008, 98, 213–226. [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki, P.L.; Van Meijl, H.; Kneirim, A.; Banse, M.A.; Belling, M.; Helming, J.F.; Leibert, T.; Lentz, S.; Margraf, O.; Matzdorf, B.; et al. SCENAR 2020. Scenario Study on Agriculture and the Rural World; European Commission, Directorate-General Agriculture and Rural Development and Directorate, G. Economic analysis and evaluation. Contract No. 30–CE–0040087/00-08; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 2007; ISBN 978-92-79-05441-9.

- Westhoek, H.J.; Van den Berg, M.; Bakkes, J.A. Scenario development to explore the future of Europe’s rural areas. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 114, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.; Leitão, P.; Sikor, T. Comparing the determinants of cropland abandonment in Albania and Romania using boosted regression trees. Agric. Syst. 2013, 117, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto Correia, T. Threatned landscape in Alentejo, Portugal: The “montado” and other “agro-silvo pastoral systems”. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1993, 24, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.N.; de Almeida, A.C.; Coelho, C.O.A. Impact of land use and cover type on runoff and erosion in a marginal area of Portugal. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatrava, J.; Barbera, G.G.; Castillo, V.M. Farming practices and policy measures for agricultural soil conservation in semi-arid mediterranean areas: The case of Guadalentin basin in southeast Spain. Land Degrad. Dev. 2011, 22, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Hernández, C.; Cánovas-García, F.; Alonso-Sarria, F.; Romero-Díaz, A.; Belmonte-Serrato, F. Cartografía de áreas agrícolas abandonadas mediante técnicas de SIG y fotointerpretación. In Comarcas de la Huerta y Campo de Murcia y Alto Guadalentín; Universidad de Murcia, Departamento de Geografía: Murcia, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Romero, E.; Cammeraat, E.; Pérez-Cardiel, E.; Lasanta, T. Effects of secondary succession and afforestation practices on soil properties after cropland abandonment in humid Mediterranean mountain areas. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 228, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiso, E.; Lasanta, T. El espacio agrario en el valle del Linares: Características y utilización reciente. Berceo 1990, 118, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuán, Y.; Arnáez, J.; Beguería, S.; Lana-Renault, N.; Lasanta, T.; Gómez-Villar, A.; Álvarez-Martínez, J.; Coba-Pérez, P.; García-Ruiz, J.M. Woody plant encroachment following grazing abandonment in the subalpine belt: A case study in northern Spain. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 1003–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, T.; Ries, J. Vegetation cover and geomorphodynamics on abandoned fields in the Central Ebro Basin (Spain). Geomorphology 2008, 102, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila Subirós, J.; Rodríguez-Carreras, R.; Varga, D.; Ribas, A.; Úbeda, X.; Asperó, F.; Llausàs, A.; Outeiro, L. Stakeholders perceptions of landscape changes in the Mediterranean mountains of the North-Eastern Iberian Peninsula. Land Degrad. Dev. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badía, A.; Pélachs, A.; Vera, A.; Tulla, A.F.; Soriano, J.M. Cambios en los usos del suelo y cubiertas del suelo y los efectos en la vulnerabilidad en las comarcas de montaña de Cataluña. Del rol del fuego como herramienta de gestión a los incendios como amenaza. Pirineos 2014, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Overmars, K. Combining top-down and bottom-up dynamics in land use modeling: Exploring the future of abandoned farmlands in Europe with the Dyna-CLUE model. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Land use/cover maps | Primary outputs of the simulation whose land-use classes refer to: residential, industry, agricultural systems, agricultural land abandonment, forest and naturally vegetated areas. Spatial and temporal resolution: 100 metres; from 2012 to 2030. | LUISA platform [49,50] |

| Biophysical | ||

| Length of growing period | Number of days when the average daily temperature is above a certain temperature threshold. | [51] |

| Soil Organic matter | Topsoil (0–30 cm) organic matter content. | [52,53] |

| Soil texture | Soil texture with less than 18% clay, more than 65% sand, or which have stones, boulders or rock at the surface are considered not favourable for crop growth. | [54] |

| Root depth | To ensure maximum root development due to the presence of specifics horizon that cannot be penetrated by the roots. | [54] |

| Soil pH | Spatial layer of topsoil pH which represents the pH given for the dominant soil; extreme values are considered not favourable for crop growth. | [53,55] |

| Salinity and sodicity | Medium or high salinity concentration areas are proposed as unfavourable agricultural conditions. Soil sodicity is a land characteristic for which the proportion of absorbed sodium in the soil clay fraction is too high for plants to perform or survive. | [54] |

| Precipitation | Total mean annual precipitation calculated as the sum of the mean monthly precipitation. | [55] |

| Soil drainage | It refers to the maintenance of the gaseous phase in soil pores by the removal of water. Imperfect, poor and very poorly drained soils are considered not favourable for crop growth. | [54] |

| Slope | Flat areas or with a slope <8% are the most appropriated for crop growth. Slopes in excess of 16% will provide difficulty for harvesting machinery. | [56] |

| Agroeconomic and farm structure | ||

| Age of farmers | The number of farmers > 65-year-old over the total number of farmers. It is assumed that abandonment is more likely to occur when the farmer is close to the retirement age. NUTS3 level. | Data: Holders above 65_ef_r_farm2007.xls [57] |

| Farmer qualification | Share of farmers with practical experience with regard to the total number of trained farmers. Farmer with high qualification invest more in human capital, etc., thus preventing farmland abandonment. NUTS0 level. | Data: Total_ef_mptrainman.xls, Practicalexperience_ef_mptrainman.xls [57] |

| Farm size | Share of farms (UAA) under 50% of the average size region (NUTS3 level). In this way, large farms compared to small (fragmented) farms are usually more competitive and viable from an economic point of view. | Data: Size and type_ef_r_farm-3.xls [57] |

| Rent paid | Rent paid is used as a proxy of the strength or weakness of the land market. It is assuming that high rental prices lead to high demand for agricultural land and therefore, a low risk of abandonment. Units: Euro. | [58] |

| Rented UAA | Share of the rented UAA over the total UAA. It is assumed that the lower the rented UAA, the higher the abandonment risk. Units: ha | [58] |

| Farm income | This variable is used as a proxy of economic performance compared to the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. National GDP is a proxy of national income. It is assumed that the lower the income, the higher the abandonment risk. Units: Euro. | Data: nama_gdp_c.xls [57,58] |

| Farm investment | This variable can be interpreted as a proxy of improving (new machinery, new technics) and continuing farm activities, hence reducing the risk of abandonment. Units: Euro. | [58] |

| Farm scheme (subsidies) | The indicator is computed by using the variable “Farm subsidies” normalized by the UAA sample area. It is assumed that the lower the subsidies, the higher the abandonment risk. Units: Euro. | [58] |

| Demographic and regional context | ||

| Low population density | Population density below 50 inhabitants/km2 is considered very low populated areas. The modelling mechanism counts for each cell the allocated residents within a surrounding kernel with an area of (approximately) 1 km2; then, it is possible to identify the cells with less than 50 inhabitants inside the surrounding kernel. | LUISA population density map based on EUROPOP2013 [30] |

| Remote areas | Remote areas are represented as a dynamic map of travelling time to the nearest town. Thus, remote areas are identified as those that are further than 60 minu away from towns. | [13,14,59] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perpiña Castillo, C.; Coll Aliaga, E.; Lavalle, C.; Martínez Llario, J.C. An Assessment and Spatial Modelling of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain (2015–2030). Sustainability 2020, 12, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020560

Perpiña Castillo C, Coll Aliaga E, Lavalle C, Martínez Llario JC. An Assessment and Spatial Modelling of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain (2015–2030). Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020560

Chicago/Turabian StylePerpiña Castillo, Carolina, Eloína Coll Aliaga, Carlo Lavalle, and José Carlos Martínez Llario. 2020. "An Assessment and Spatial Modelling of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain (2015–2030)" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020560

APA StylePerpiña Castillo, C., Coll Aliaga, E., Lavalle, C., & Martínez Llario, J. C. (2020). An Assessment and Spatial Modelling of Agricultural Land Abandonment in Spain (2015–2030). Sustainability, 12(2), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020560