Transformational Collaboration for the SDGs: The Alianza Shire’s Work to Provide Energy Access in Refugee Camps and Host Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

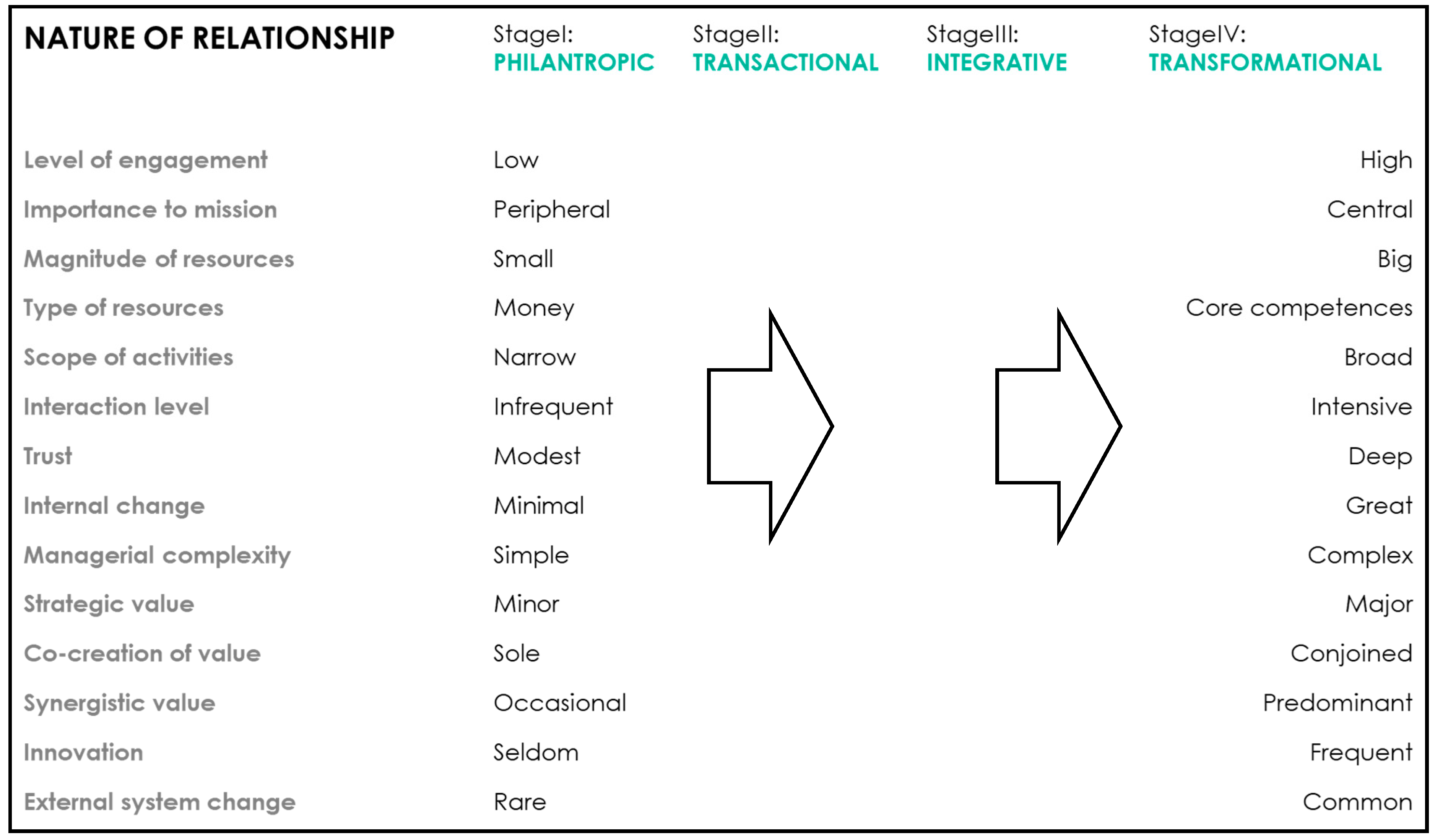

2. Theoretical Context of Partnerships

3. Research Approach

3.1. Research Aims and Scope

- To analyze the evolution of the transformational character of the Alianza Shire and evaluate its position within the CVC spectrum.

- To characterize the role of Universidad Politécnica de Madrid’s Innovation and Technology for Development Centre (itdUPM) as an intermediary actor in fostering the transformational character of the Alianza Shire through the identification of key intermediary activities.

3.2. Methodology

3.3. Cvc Framework as an Assessment Tool

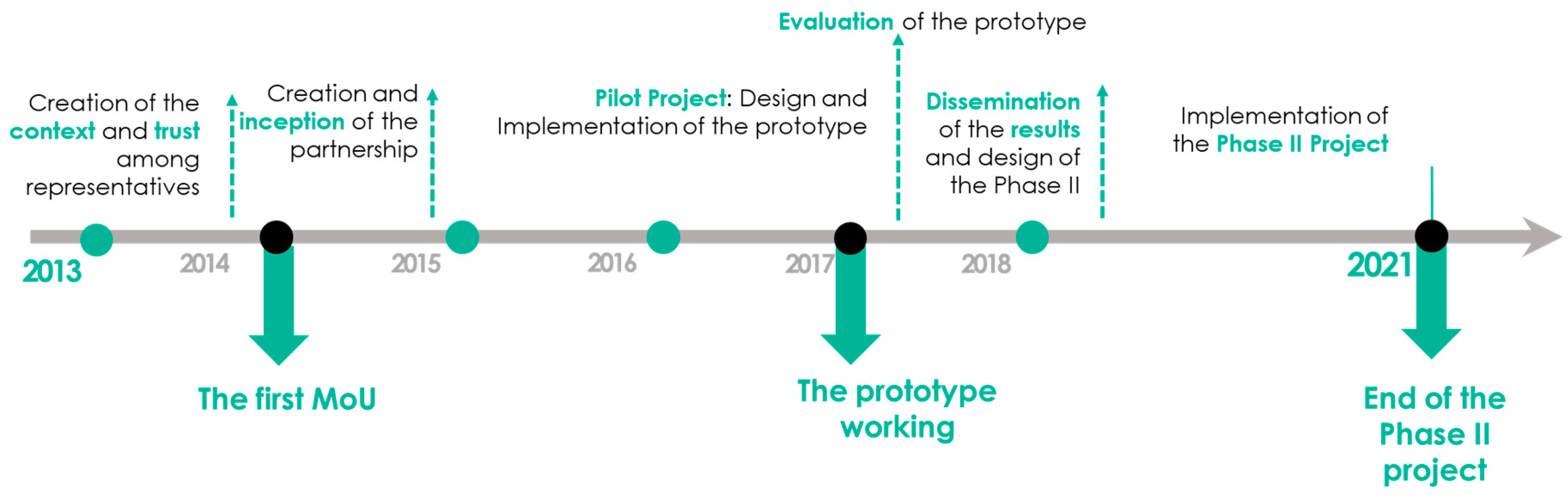

4. The Case of the Alianza Shire

5. Results: CVC Analysis of the Alianza Shire

5.1. Organizational Engagement

5.2. Resources and Activities

5.3. Partnership Dynamics

5.4. Impact

- Product—changes in products or services: High quality products that are framed holistically such as use of third generation Solar Home Systems (SHS), robust and adapted LED street lighting technology, high quality electrical grid materials and augmented reality equipment for training.

- Process—changes in the ways services are created or delivered: Development of a management model based on guaranteeing sustainability through diverse contributions and coordination among different actors. Six micro-enterprises (between refugees and people from host communities) with their associated business models will be created to ensure sustainability in the management and maintenance of the 1700 SHS.

- Position—changes in the way services are presented to the user and how these are communicated and reframed by government and other actors: Positioning energy supply as a central element in the management of the Shire refugee camps and as a catalyst for new development possibilities. This has been possible thanks to the integration of two key partners in the field and co-creation efforts with them: ARRA (Ethiopian Agency for Refugee & Returnee Affairs, responsible for managing refugee camps in collaboration with UNHCR) and the Ethiopian Electric Utility.

- Paradigm—changes in the underlying mental models that shape what the service offers: Contributing to a shift in the traditional humanitarian response mindset by presenting refugee camps as a source of innovation where refugee and local communities can participate in the design and implementation of solutions to the challenges they face. This also suggests that non-traditional actors such as academic and private companies can play a clear and positive role in the humanitarian field.

5.5. Assessment of the Evolution of the Transformational Character of the Alianza Shire

6. Discussion

6.1. Results Discussion

- Individuals: the high adaptation costs of integrating individuals from different partner organizations as actors in key partnership processes (legal, security and safety, procurement, etc.) hinder interaction. Some roles in particular are not fully understood during the initial stages of interaction. For example, the partnership facilitator is commonly confused with the Project Office, the partner organizations are occasionally considered to be external stakeholders and competitors and local partners in the field are at times viewed as service or product suppliers.

- Partner organizations: Internal consolidation of the partnership is a long-term process. The silos that exist in all organizations, especially large international enterprises or public bodies such as those participating in the Alianza Shire, limit the involvement of different departments and business units and thus reduce the potential for co-creation within and between organizations.

- External environment: Formal management, monitoring and accountability mechanisms are not adapted for working in a long-term partnership with a transformational aspiration. This may undermine organizational confidence in processes involving fund allocation, sharing of responsibility and the participation of external actors.

- Generation of a collaboration context: Promoting organizational engagement by encouraging partners from different sectors to assume their primary role and generating trust through a deeper understanding of the identities and views of different parties [5].

- Design: Promoting the generation of shared value with co-creation of activities among partners and facilitation of a framework for systematic management, coordination and continuous improvement.

- Mediation: Facilitating key interaction processes, creating a neutral space for dialogue and addressing procedures that are not adapted for long-term transformational partnerships.

- Promotion of key transversal processes such as innovation, learning, gaining wider influence, etc.

6.2. Limitations of the Study

6.3. Future Directions of the Research

- In order to simplify the analysis and avoid too many interactions between elements, it is helpful to group the wide variety of elements of the CVC framework into categories. This paper presents a proposal for grouping these elements into "organizational engagement", "resources interaction", "partnership dynamics" and "impact" but other groupings may also be appropriate.

- Increase the granularity of the analysis so that the interaction of a number of common elements within each category can be analyzed, for example; the partnership’s project portfolio, its ecosystem of people and organizations, and the tools and methodologies used.

- Incorporate analysis of the wider context which the project aims to influence, including political changes and regulatory frameworks, etc. These elements could be included in the category of "partnership dynamics".

6.4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Element | Description | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Alianza Shire Memorandum of Understanding (Pilot Project) | Agreement for the creation, operation and evaluation of the Public-Private Humanitarian Action Partnership for the development of the Pilot Project. The purpose of the Agreement is to establish the necessary working mechanisms for the development of the Pilot Project, through the creation of a multi-stakeholder humanitarian action partnership between the members. | Signed by the 5 Alianza Shire members. The members agree to share the common objective of developing innovative and sustainable solutions that consider the needs and aspirations of the designated population. |

| Alianza Shire members Agreement (Phase II) | Agreement for the creation, operation and evaluation of the Public-Private Humanitarian Action Partnership for the development of the Phase II Project. The purpose of the Agreement is to establish the necessary working mechanisms for the development of the Phase II Project through the creation of a multi-stakeholder humanitarian action partnership between the members. The Agreement includes a section that gathers the overall governing processes and principles of the partnership that have been further developed together with the Steering Committee. | Signed by the 5 members of the Alianza Shire. Contents and wording finalized (process of almost a year’s duration), pending authorization from public administration. The members agree to share the common objective of developing innovative and sustainable solutions that consider the needs and aspirations of the designated population. The Agreement includes aspects such as the governing structures and member representatives in each Committee, commitments and economic contributions; code of conduct; security management and multiple administrative, legal and binding aspects. |

| Project Management Plan (PMP) | Intended to be an operational guide for the integrated management of the Project. It is a tool at the disposal of the different partnership organs and seeks to organize their work. It establishes the functions and responsibilities of each body and the different project management processes and procedures. It is a tool that facilitates the execution of the project in all its stages. | The PMP aims to be useful, easy to use, agreed among all parties and subject to continuous improvement. It follows international standards such as the PMBOK (Project Management Body of Knowledge) and ISO 9001: 2015 It gathers, among other elements, the scope, cost, time, risk, quality and communication management protocols, as well as the organizational structure and main innovation, execution and coordination processes. The PMP includes, among others, key processes such as internal training, knowledge management, strategic evaluation, seminars and community participation processes. |

| Security Agreement | The purpose of this agreement is to govern the terms and conditions applicable to the collaboration of the members and ZOA in order to ensure the security of the Project and the personnel travelling to it during their time in the Tigray Region. It includes both ZOA and member obligations, security incident management processes and different legal and administrative aspects. | The process has been ongoing for well over a year. It has involved the participation of the legal and security departments of all members. Signing was accelerated (and made feasible) due to the personal commitment of the former ZOA Company Director in Ethiopia. It has involved the creation of an ad-hoc evacuation plan for the Alianza Shire, an internal emergency situations management protocol, the creation of the Alianza Shire Emergency Committee and an addendum to the agreement. |

| Communications Protocols | The communications protocols govern the Alianza Shire external communication and visibility Procedures. They include the Communication and Visibility Plan, the Alianza Shire Key Messages document and communication guidelines for partners in the field. | All the protocols have been produced by itdUPM, some of which have been revised by members and approved by the Communication Committee. The Communication and Visibility Plan was rejected by the Steering Committee on three occasions before its definitive approval. Interest has specially been focused on the visibility of each member in the communication actions and materials. |

| Agreements with partners in the field | These agreements seek to govern the relationship between local partners in the field and the Alianza Shire with regard to the implementation of the project. Some agreements—Memorandums and Letters of Understandings (MoUs and LoUs)—are non-binding documents in which the organizations mutually recognize each other and reflect their intention to collaborate. Others—Grants—are binding documents through which a partner agrees to work in the project, assume specific responsibilities, and obtain an economic contribution. | The MoUs and LoUs reflect willingness but do not ensure specific collaboration or support. The Grants are based on traditional cooperation schemes whereby an organization assumes the responsibility of executing a series of activities and achieves certain goals. The Grants and, to a lesser extent, the MoUs and LoUs, may be seen as contractual agreements for service exchange in which there is little room for transformation or innovation. |

Appendix B

| Element | Description/Key Indicators | Additional Considerations | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot Project | Training for refugees and host community (practical part directly related to grid extension works) Creation of group of operators under Norwegian Refugee Council 4 Km of street lighting All communal services connected to the grid 1 refugee camp (8000 people) | Positive impact (according to preliminary assessment) Demonstration of partnership-based approach and driver for Phase II Solutions implemented have not proven to be sustainable (Operator team and overall grid situation) Several lessons learnt for consideration in Phase II | Alianza Shire project description Alianza Shire case study Appearances in mass-media Pilot Project Technical Report |

| Phase II Project | Training for Ethiopian Electric Utility (EEU) staff and Training of Trainers approach Training for refugees and host community (practical part directly related to grid works) Labor insertion of operators in EEU Connection of 450 private businesses in the camps +25 Km of street lighting All communal services connected to grid 4 refugee camps and host communities (+ 40, 000 people) Training for refugees and host community as entrepreneurs 6 new businesses operating under an umbrella organization 6 Photovoltaic Electrification Committees 1700 Solar Home Systems (SHS) | Solutions based on existing technologies and approaches (connection to grid) Coordination efforts with other projects based on avoiding overlaps Strong collaboration with the EEU (training, regularization of connections, project approval, economic contribution, etc.) Focus on sustainability (great efforts placed on developing an appropriate methodology for trainings. Innovative approach as refugees and host communities are targeted together and treated as equals Solutions based on this approach have proven to be effective in different contexts Sustainability built upon market-based approach (developed by thematic experts) Coordination efforts to avoid negative impacts with other approaches (free delivery) Strong sensitization component as this model is not common in field | Alianza Shire Phase II Action Document Alianza Shire project description MoU signed between the Ethiopian Electric Utility, The Agency for Refugees and Returnees Affairs, Stitching ZOA and AECID Technical pre-design of Project Alianza Shire General Brochure Alianza Shire Technical Brochure |

| Steering Committee | The Steering Committee is made up of senior managers from each partnership member. The Steering Committee is responsible for guiding the strategic direction of the partnership and ensuring the necessary resources for the implementation of the Project. Strategic decisions affecting the Alianza Shire are made unanimously. | Periodic—bimonthly—face-to-face meetings Members are represented by high-level executives UNCHR Spain participates in every meeting (invited organization as per the Agreement) Decision making processes are mainly based on the resolution of critical aspects of project development although aspects such as innovation are also included Meetings are chaired and guided by itdUPM | Alianza Shire MoU (Pilot Project) Alianza Shire members Collaboration Agreement (Phase II Project) Project Management Plan Security Agreement Iberdrola CEO declarations OCHA director in UPM with SECIPIC |

| Management Committee | The Management Committee is responsible for deciding on the planning, design, implementation and monitoring and evaluation of the Phase II Project. It is composed of one or two individuals from the partners who are supported by groups of experts within their own organizations. Decisions on the Project are taken by consensus in the Management Committee. Each member shall consult beforehand with other members on any decision it takes concerning the Project that affects one or more members and/or the Project itself. | Periodic-monthly- face-to-face Members are represented by senior experts There is a strong monitoring component based on monthly reports. The Management Committee is the space in which the technical work of each organization is brought together, and shared operational and technical decisions taken. Meetings are chaired and guided by itdUPM | Alianza Shire members Collaboration Agreement (Phase II Project) Project Management Plan Security Agreement |

| Project Office (PO) | The PO is formed exclusively for the integration and coordination of necessary elements for the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the Project. The Project Office is in charge of articulating these different work levels. It participates, through designated representatives and by invitation, in the different levels and decision-making bodies of the Alianza Shire with the objective of reporting on the status of the Project. It follows the guidelines established by the Management Committee. | Periodic-weekly-meetings Meetings are chaired and guided by itdUPM The PO is formed by four individuals and it is permanently present in the three locations of the project (Madrid, Addis Ababa and Shire) Although it is conceived as the Management Committee implementing branch, apart from the execution, some design and innovation aspects emerge from the PO. | Alianza Shire members Collaboration Agreement (Phase II Project) Project Management Plan |

| Communications Committee | It designs and executes the external communication and visibility strategy external to the partnership, devising communications protocols and briefs as well as organizing actions that promote visibility. Communications decisions prioritize all products generated by the Project and make visible the participation of all members of the partnership. | Periodic-tri-monthly-face-to-face meetings Members are represented by communication staff of the partners. The decision-making capacity of these representatives varies significantly between organizations Decisions are countersigned by the Steering Committee Special relevance of each member’s visibility—including the presence of the corresponding logo. Meetings are chaired and guided by itdUPM UNCHR Spain participates in every meeting (invited organization as per the Agreement) | Alianza Shire members Collaboration Agreement (Phase II Project) Project Management Plan Communication Protocols |

| Organizations in the Field | The relationship with these organizations is theoretically based on the grants and MoUs signed with them. The participation and linkage of these organizations to the project differs substantially. Long-term relationships are fostered with the organizations that may be attached to the project once it has been finished (EEU and trained operators, for instance). Alianza Shire is permitted to operate in refugee camps and is widely recognized by authorities. Coordination with organizations that are not ‘formally linked’ to the project is boosted. One of these organizations, ZOA, participates in weekly coordination meetings and proactive participation and opinion sharing is sought | The main organizations in the field are the following: International NGOs (Implementing partners): ZOA, Norwegian Refugee Council, Don Bosco—Jugend Eine Welt Governmental bodies: Agency for Refugee and Returnees Affairs (ARRA), several ministries and regional bureaus. Local authorities: Woredas and Kebele administrations Refugee bodies: Refugee Central Committees, Women Associations, etc. Ethiopian Electric Utility: Regional, district and local levels UN organizations: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) | Alianza Shire Agreements with other partners |

Appendix C

| Organization | Document | Statements Related to SDGs and Partnerships |

|---|---|---|

| AECID | Master Plan (2018–2021) | “The Spanish International Cooperation will promote the construction and strengthening of partnerships with the different actors committed to achieving the SDGs [….]. These will be promoted among the different actors of international cooperation, public, private and civil society, from Spain and our partner countries, to maximize synergies, complement resources, enrich learning and increase the development impact of interventions” and "the role of the private sector in our humanitarian action will be enhanced, where there is added value ".t |

| Iberdrola | Mission statement (2016) | “Our mission is to create value in a sustainable way in the development of our activities for society, citizens, customers and shareholders, being the leading multinational group in the energy sector that provides quality service through the use of environmentally friendly energy sources [….]”t |

| Acciona | Mission statementt (2016) | “Our mission is to be leaders in the creation, promotion and management of Infrastructure, Water, Services and Renewable Energy actively contributing to social welfare, sustainable development and the generation of value for our stakeholders”t |

| Signify | Mission statementt (2018) | Stresses the environmental dimension of their activities and the commitment of the organization to making “people's lives more comfortable and safe, more productive companies and more livable cities”.t |

| itdUPM | Statutet (2016) | […] “promote the generation of awareness, knowledge and innovative solutions that contribute to the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals and, thus, to human and sustainable development”. |

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution 70/1 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 25 September 2015. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- United Nations. The Road to Dignity by 2030: Ending Poverty, Transforming All Lives and Protecting the Planet. 2014. Available online: http://digitallibrary.un.org/record/785641 (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, D. A New Approach to Partnerships for SDG Transformations. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Tulder, R. Business & The Sustainable Development Goals: A Framework for Effective Corporate Involvement; RSM: Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon, M.; Cox, M.E. Collaboration, Adaptation, and Scaling: Perspectives on Environmental Governance for Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Summary of the First Global Refugee Forum by the Co-Convenors. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/events/conferences/5dfa70e24/summary-first-global-refugee-forum-co-convenors.html (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Global Trends—Forced Displacement in 2018. 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/globaltrends2018/ (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- Moving Energy Initiative. Available online: https://mei.chathamhouse.org (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- Safe Access to Fuel and Energy (SAFE). Available online: http://www.safefuelandenergy.org (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR). Global Plan of Action (GPA) for Sustainable Energy Solutions in Situations of Displacement. Available online: https://unitar.org/sustainable-development-goals/peace/our-portfolio/global-plan-action-gpa-sustainable-energy-solutions-situations-displacement (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- United Nations. New York Declaration for Refugees and Migrants. Resolution 71/1 Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 3 October 2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/71/1 (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- International Finance Corporation; World Bank Group. Private Sector and Refugees. Pathways to Scale; Bridgespan Group: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/04c889b0-1047-4c2c-a080-e14afb9a4bf2/201905-Private-Sector-and-Refugees-Summary.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=mGiP6tr (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Editorial. The Power to Respond. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellanca, R. Sustainable Energy Provision among Displaced Populations: Policy and Practice; Chatham House, The Royal Institute of International Affairs: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg-Jansen, S.; Tunge, T.; Kayumba, T. Inclusive Energy Solutions in Refugee Camps. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 990–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boodhna, A.; Sissons, C.; Fullwood-Thomas, J. A Systems Thinking Approach for Energy Markets in Fragile Places. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, J.; Rothkop, J.; Miller, G. Off-grid Solar PV Power for Humanitarian Action: From Emergency Communications to Refugee Camp Micro-grids. Procedia Eng. 2014, 78, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katie Whitehouse. Adopting a Market-Based Approach to Boost Energy Access in Displaced Contexts; The Moving Energy Initiative; Chatham House: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation. The Alianza Shire, the First Public-Private Partnership for Humanitarian Action in Spain, Presents the Results of Its Pilot Project In Ethiopia. 2017. Available online: http://www.aecid.es/ES/Paginas/Sala%20de%20Prensa/Noticias/2017/2017_05/05_29_shire.aspx (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Eras-Almeida, A.A.; Fernández, M.; Eisman, J.; Martín, J.G.; Caamaño, E.; Egido-Aguilera, M.A. Lessons Learned from Rural Electrification Experiences with Third Generation Solar Home Systems in Latin America: Case Studies in Peru, Mexico, and Bolivia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataix, C.; Romero, S.; Mazorra, J.; Moreno, J.; Ramil, X.; Stott, L.; Carrasco, J.; Lumbreras, J.; Borrela, I. Working for Sustainability Transformation in an Academic Environment: The Case of ItdUPM. In Handbook of Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Mifsud, M., Shiel, C., Pretorius, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.; Mach, E. Policies for Increased Sustainable Energy Access in Displacement Settings. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 1000–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Patel, L. Innovative Financing for Humanitarian Energy Interventions; The Moving Energy Initiatives; Chatham House: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jonathan Rouse. Private-Sector Energy Provision in Displacement Settings; The Moving Energy Initiative; Chatham House: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, J.E.; Seitanidi, M.M. Collaborative Value Creation: A Review of Partnering between Nonprofits and Businesses: Part I. Value Creation Spectrum and Collaboration Stages. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 726–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Shaping Sustainable Change: The Role of Partnership Brokering in Optimising Collaborative Action; Routledge: Abington UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Howells, J. Intermediation and the role of intermediaries in innovation. Res. Policy 2006, 35, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T.; Hielscher, S.; Seyfang, G.; Smith, A. Grassroots innovations in community energy: The role of intermediaries in niche development. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 868–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L. Understanding the Role of the Broker in Business Non-Profit Collaboration. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, R.E.; Bale, C.S.; Powell, M.; Gouldson, A.; Taylor, P.G.; Gale, W.F. The Role of Intermediaries in Low Carbon Transitions–Empowering Innovations to Unlock District Heating in the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, R.; April, K. On the Role and Capabilities of Collaborative Intermediary Organisations in Urban Sustainability Transitions. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçüksayraç, E.; Keskin, D.; Brezet, H. Intermediaries and Innovation Support in the Design for Sustainability Field: Cases from the Netherlands, Turkey and the United Kingdom. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 101, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennyson, R. The Brokering Guidebook. Navigating Effective Sustainable Development Partnerships; IBLF: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. The Multi-Level Perspective on Sustainability Transitions: Responses to Seven Criticisms. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; Fuenfschilling, L.; et al. An Agenda for Sustainability Transitions Research: State of the Art and Future Directions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, I.; Kanda, W. A Typology of Intermediary Organizations and Their Impact on Sustainability Transition Policies. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2018, 29, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, P.; Boon, W.; Hyysalo, S.; Klerkx, L. Towards a Typology of Intermediaries in Sustainability Transitions: A Systematic Review and a Research Agenda. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, F.; Bush, R.; Webb, J. Emerging Linked Ecologies for a National Scale Retrofitting Programme: The Role of Local Authorities and Delivery Partners. Energy Policy 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, K.; Jurgilevich, A.; Pietikäinen, J.; Korhonen-Kurki, K. Universities Responding to the Call for Sustainability: A Typology of Sustainability Centres. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, H.A.; Redzuan, M.B. The Role of NGOs in Promoting Empowerment for Sustainable Community Development. J. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 30, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Stakeholder Engagement in Partnerships. Who Are the ‘Stakeholders’ and How Do We ‘Engage’ with Them; BPD Research Series; Building Partnerships for Development: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Derkzen, P.; Franklin, A.; Bock, B. Examining Power Struggles as a Signifier of Successful Partnership Working: A Case Study of Partnership Dynamics. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L. Partnership and Social Progress: Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration in Context. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, K.; Stott, L. Defining Our Terms and Clarifying Our Language. Partnersh. Strategy Soc. Innov. Sustain. Chang. 2008, 23–35. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, L.; Nilsson, B. Partnership: As a Strategy for Social Innovation and Sustainable Change; Santérus Academic Press: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, K. Partnership Accountability: Unpacking the Concept; Building Partnerships for Development: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, K. Plotting Partnerships: Ensuring Accountability and Fostering Innovation; Practitioner Note Series; Business Partners for Development (BPD) Water and Sanitation Cluster: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, S.; Roessler, D. The Formation of Cross-Sector Development Partnerships: How Bridging Agents Shape Project Agendas and Longer-Term Alliances. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, L.; Scoppetta, A. Adding Value: The Broker Role in Partnerships for Employment and Social Inclusion in Europe. Betwixt Between J. Partnersh. Brok. 2013, 1, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Crane, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spence, L.J.; Matten, D. Contesting the Value of “Creating Shared Value”. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 56, 130–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beschorner, T.; Hajduk, T. Creating Shared Value. A Fundamental Critique. In Creating Shared Value–Concepts, Experience, Criticism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. The Case Study as a Serious Research Strategy. Knowledge 1981, 3, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. The Case Study Method as a Tool for Doing Evaluation. Curr. Sociol. 1992, 40, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galunic, D.C.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Architectural Innovation and Modular Corporate Forms. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 1229–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Yazan, B. Three Approaches to Case Study Methods in Education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods; Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zelikow, P.; Allison, G. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 1999; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Waters, J.A. Tracking Strategy in an Entrepreneurial Firm. Acad. Manag. J. 1982, 25, 465–499. [Google Scholar]

- Stott, L. Partnership Case Studies in Context; Partnering Initiative, IBLF: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamanen, M.; Skålén, P. Collective–Conflictual Value Co-Creation: A Strategic Action Field Approach. Mark. Theory 2015, 15, 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkerhoff, J.M. Assessing and Improving Partnership Relationships and Outcomes: A Proposed Framework. Eval. Program Plan. 2002, 25, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partnership Learning Loop. Available online: http://www.learningloop.nl/ (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Caplan, K.; Gomme, J.; Mugabi, J.; Stott, L. Assessing Partnership Performance: Understanding the Drivers for Success; Building Partnerships for Development (BPDWS): London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wigboldus, S.; Brouwers, J.; Snel, H. How a Strategic Scoping Canvas Can Facilitate Collaboration between Partners in Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Ethiopia Comprehensive Registration. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/58 (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Alianza Shire. About Us. Available online: http://www.itd.upm.es/alianzashire/?lang=en (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- Palomo, A.G. Alianza Shire: El proyecto español que ilumina a los refugiados. El País. 30 May 2017. Available online: https://elpais.com/elpais/2017/05/30/planeta_futuro/1496135279_476619.html (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Horn of Africa, Ethiopia. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/horn-africa/ethiopia_en (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Herrera Mancilla, A.O. Public Private Partnerships in the Humanitarian Aid. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Iberdrola. Electricity for All Program. Available online: https://www.iberdrola.com/conocenos/sociedad/colectivos-vulnerables/programa-electricidad-todos (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Iberdrola. Sustainability Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.iberdrola.com/accionistas-inversores/informes-anuales (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Acciona. Sustainability Report. 2017. Available online: https://informeanual2017.acciona.com/sostenibilidad/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Signify. Sustainability Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.signify.com/es-es/sobre-nosotros/news/press-releases/2019/20190516-signify-publishes-its-sustainability-report-2018 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- High Commissioner for the 2030 Agenda. Spanish Government. Publicación del Informe de Progreso Sobre la Implementación de la Agenda 2030 en España. Available online: https://www.agenda2030.gob.es/es/publicacion-del-informe-de-progreso-sobre-la-implementacion-de-la-agenda-2030-en-espana (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. UPM Seminars: Technology and Innovation for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.upm.es/Investigacion/difusion/SeminariosUPM (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Project Management Institute. Standards Development Process. Available online: https://www.pmi.org/pmbok-guide-standards/about/development (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Kotter, J.P. Accelerate: Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World; Harvard Business Review Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. UPM Platform on Refugees. NAUTIA Methodology. Available online: https://blogs.upm.es/refugiadosupm/nautia-methodology/ (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Mazorra Aguiar, J.; Lumbreras Martín, J.; Ortiz Marcos, I.; Hernández Díaz-Ambrona, C.G.; Carretero Díaz, A.M.; Egido Aguilera, M.Á.; Gesto Barroso, B.; Mancebo Piqueras, J.A.; Pereira Jerez, D.; Sierra Castañer, M. Using the Project Based Learning (PBL) Methodology to Assure a Holistic and Experimential Learning on a Master’s Degree on Technology for Human Development and Cooperation. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2016, 32, 2304–2317. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Case Study: Alianza Shire, Energy Access to Refugees. 2017. Available online: http://www.itd.upm.es/alianzashire/case-study-alianza-shire-energy-access-to-refugees/?lang=en (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Multilateral Investment Fund/Inter-American Development Bank & Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Partnerships for Innovation in Access to Basic Services. 2014. Available online: http://www.itd.upm.es/portfolio/alianzas-para-la-innovacion-en-el-acceso-servicios-basicos-cinco-estudios-de-caso/ (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Prieto-Egido, I.; Simó-Reigadas, J.; Martínez-Fernández, A. Interdisciplinary Alliances to Deploy Telemedicine Services in Isolated Communities: The Napo Project Case. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pade, C.; Mallinson, B.; Sewry, D. An Elaboration of Critical Success Factors for Rural ICT Project Sustainability in Developing Countries: Exploring the Dwesa Case. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2008, 10, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, M.L.; Carvalho, M.M. Key Factors of Sustainability in Project Management Context: A Survey Exploring the Project Managers’ Perspective. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Økland, A. Gap Analysis for Incorporating Sustainability in Project Management. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 64, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Alianza Shire in the Humanitarian Energy Conference, Addis Abeba. 2019. Available online: http://www.itd.upm.es/alianzashire/alianza-shire-in-the-humanitarian-energy-conference-addis-abeba-julio-2019/?lang=en (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation. The Alianza Shire, Selected as a Best Practice at the Global Refugee Forum. Available online: http://www.aecid.es/EN/Paginas/Sala%20de%20Prensa/Noticias/2019/2019_12/16_shire.aspx (accessed on 31 December 2019).

- Fowler, A.; Biekart, K. Multi-stakeholder Initiatives for Sustainable Development Goals: The Importance of Interlocutors. Public Adm. Dev. 2017, 37, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, K.W.; Genschel, P.; Snidal, D.; Zangl, B. International Organizations as Orchestrators; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moeller, S.; Ciuchita, R.; Mahr, D.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Fassnacht, M. Uncovering Collaborative Value Creation Patterns and Establishing Corresponding Customer Roles. J. Serv. Res. 2013, 16, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lente, H.; Hekkert, M.; Smits, R.; Van Waveren, B. Roles of Systemic Intermediaries in Transition Processes. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2003, 7, 247–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Original CVC Framework Variables |

|---|---|

| Organizational engagement | Level of engagement Importance to mission |

| Resources and activities | Type of resources Magnitude of resources Scope of activities Managerial complexity |

| Partnership dynamics | Interaction Trust Internal change |

| Impact | Co-creation of value Synergistic value Strategic value Innovation External system change |

| Partnership Analysis Framework or Tool | Main focus Area |

|---|---|

| Collective-Conflictual Value Co-creation | Conflict between actors leads to innovation or general repositioning and impacts future value co-creation. |

| Partnership Outcomes Assessment | Improvements in partnership practice and exploration of a partnership’s contribution to performance and outcomes. |

| Partnership Learning Loop | Focuses on reinforcement of collaboration between partners through different partnership layers. |

| Partnership Performance Assessment | Analyses partnership performance and effectiveness using three groupings of drivers: the external context, the organizational environment and the individuals representing each partner organization. |

| The MSP Guide | Wide range of tools for assessing participation. |

| Collaborative Value Creation | Stresses the value creation process among partners with an evolutionary perspective and a transformative aspiration. |

| Pilot Project: The Prototype | Phase II: The Project |

|---|---|

| 1 refugee camp | 4 refugee camps and host communities |

| 8000 refugees | 60,000 refugees 17,000 people from the host community |

| 4 km of street lighting | 25 km of street lighting 100% connection of Communal Services Connection of 450 private businesses |

| Training of refugees | Managerial training for the Ethiopian Electric Utility’s regional managers Technical training for the Ethiopian Electric Utility’s field staff Training of Trainers for Implementing Partner staff Training of refugees and host community |

| Trained refugees working for NGO in the camps | Trained refugees and host community included in Ethiopian Electric Utility structure |

| Only on grid component (street lighting and electrical grid improvement) | On grid in 4 camps + 1700 third generation Solar Home Systems (SHS) Creation of 6 micro-businesses owned by refugees and host community—in charge of the operation and maintenance of the SHS |

| Total budget of 500,000 € (funds and in-kind contributions) | Total budged of 4,700,000 € (funds and in-kind contributions) |

| Nature of Relationship (CVC Framework) | Status at Start (2014) | Current Status (2019) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational engagement | Level of engagement | Moderate | High |

| Importance to mission | Peripheral | Central | |

| Resources and activities | Type of resources | Core competences | Core competences |

| Magnitude of resources | Small | Big | |

| Scope of activities | Narrow | Broad | |

| Managerial complexity | Simple | Complex | |

| Partnership dynamics | Interaction level | Low | Intensive |

| Trust | Modest | Medium | |

| Internal change | Minimal | Medium | |

| Co-creation of value | Medium | High | |

| Synergistic value | Occasional | Predominant | |

| Impact | Strategic value | Medium | Major |

| Innovation | Medium | Frequent | |

| External system change | Small | Significant | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno-Serna, J.; Sánchez-Chaparro, T.; Mazorra, J.; Arzamendi, A.; Stott, L.; Mataix, C. Transformational Collaboration for the SDGs: The Alianza Shire’s Work to Provide Energy Access in Refugee Camps and Host Communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020539

Moreno-Serna J, Sánchez-Chaparro T, Mazorra J, Arzamendi A, Stott L, Mataix C. Transformational Collaboration for the SDGs: The Alianza Shire’s Work to Provide Energy Access in Refugee Camps and Host Communities. Sustainability. 2020; 12(2):539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020539

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Serna, Jaime, Teresa Sánchez-Chaparro, Javier Mazorra, Ander Arzamendi, Leda Stott, and Carlos Mataix. 2020. "Transformational Collaboration for the SDGs: The Alianza Shire’s Work to Provide Energy Access in Refugee Camps and Host Communities" Sustainability 12, no. 2: 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020539

APA StyleMoreno-Serna, J., Sánchez-Chaparro, T., Mazorra, J., Arzamendi, A., Stott, L., & Mataix, C. (2020). Transformational Collaboration for the SDGs: The Alianza Shire’s Work to Provide Energy Access in Refugee Camps and Host Communities. Sustainability, 12(2), 539. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020539