Abstract

An exploration of industrial ruin sites has received sufficient attention in the past. Framed under the hybrid perspective of non-representational theory and paralleled with Ingold’s taskscape conceptualized terms, this study examines the TSA (train service area), an opencast mining ruins site in Gongguan town of Maoming, southern China, as a case locus to depict the ‘lives lived’ and the textures of the taskscape encountered by locales and to sketch out the iterative and eventful movements of human and non-human dynamic phenomena at the rural-urban interface from the 1960s to the 1980s, with the aim to re-examine the locality of one industrial city and regenerate the local culture. As actualized through ‘stories and dramatic episodes’, i.e., an art intervention of a new geographical historiography, the ‘thick’ landscape of mine transport comes to the stage as the self-landscape and of group-place scenes. In the first scene, the industrial past is evoked along the actor’s movement, through situated knowledge and through shared personhood; thus, the spirit of place is finally obtained through the aesthetic sublimation in the landscaping. In the second scene, the movement between the workplace and other rural areas, which are rural and seasonal, has balanced the gap between the urban and the rural, whilst the proximity of the village to the TSA accelerates the process of rural urbanization in this area. Among which, tea, as a non-human item, irreducibly produces a ‘structure of feeling’ and conjures up a sense of past people and past times and of customs, beliefs and localism.

1. Introduction

The deindustrialization is overwhelmed globally, industrialized cities around the world feature derelict factories, mills, warehouses, and refineries. Decayed coal mines, railroads and canals have always been symbols of human battle against an overwhelming nature now seem to return to nature as ruins [1]. The scale of these ruins site echoes the grandeur of industrial past [2], wherein you can once again sense the industrial history and industrial civilization, consign your affection and experience some kind of the ‘spirit of the site’.

The industrial past is a complex intermingling of many biographies and histories of relationships between people and between people and things. Previous studies around memory-industrial ruins site and memory-industrial remains, are mainly centred on ‘living memories’, former personal experiences of the people who memorize the mundaneness of everyday landscapes [3,4,5], memory loss and nostalgia [6] synthesis of history and memory in ethnography [7], in Island [8], de-industrialization [2], urban-rural social conflicts [9]. However, much of the literature has focused on disciplines of history, sociology, architecture and archaeology, and solely stabilised or structured via messages in texts and images [10,11] might be assumed difficultly enacting the depth and fold of the industrial ruin sites. As we have seen, memories of industrial ruins site and working-class studies are complicated still further, so, through our disciplinary desire to be interdisciplinary, we strive to draw on multiple methodologies and varied conceptual frameworks and to employ interweaving imaginaries [12]. In that case, Edensor took the lead in deploying sensations and affective resonances-the non-representational engagements with the ‘haunting’ working-class spaces of industrial past at the fringe of the city [13], and subsequently, another non-representative type studies of post-industrial landscape on ‘spectral’ [14]. Nevertheless, it has been said that in many NRT accounts, ‘memory seems underplayed in relation to its close cousins, imagination, emotion, affect’ [15]. It may be argued there is a renewed sense of a need to develop newly critical and creative means of expressing relationships between biography, history, culture and landscape.

Our research location, Maoming, is a modern industrial city, its birth was with the first blasting of oil shale rock in the opencast pit after the founding of new China, all along, there has been a legend that the rock found at the villages near the mining pit can burn. As the largest petrochemical enterprise in south China, Maoming Sinopec limited Company has a history of 60 years. The case locus TSA ruins site is located several miles away from the pit, as a portion of the train traffic network. This research was designed as doing intersectionality, framed under non-representational milieu geography, aiming to evoke the industrial past at the urban-rural border, to excavate the depth of enterprise spirit and revitalize the local culture. A cultural memory of the ‘industrial past’ is literally linked with specific iconic topographical ruin landscapes. As cultural geographical researchers, in the course of the survey, those questions that haunted us most are: how are the textures and cycles of work at the locales best encountered within the landscape of the industrial past replete with meaning? What creative strategies might be employed to reanimate the embodied relationship between individual subjects and an environment?

Non–representative theory is derived from a ‘new vitalism’ [16], along with it, ‘a new generation of cultural geographers is returning to the rich conjunction of the geo and the bio’ [17]. Ingold’s dwelling perspective of organism-and-environment offers an ontologically equivalent way of uniting the approaches of ecology and phenomenology, by contending that knowledge is perpetually produced within the field of relations established through the immersion of the actor–perceiver in a certain environmental context [18]. To actualize, he proposed the notion of ‘taskscape’, which refers to the ongoing ensemble of interrelated tasks that constitute dwelling and landscape forms are emergent in movement, overlapping rhythms of interactivity. For Ingold, movement is primary and the ‘tangle of interlaced trails constitute an evolving relational field or meshwork’ [19], the lineal movement along paths of travel is different from the lateral movement across a surface; the former type is called wayfaring, while the latter type is transport. Equally, inspired by Merleau-Ponty’s concept of embodiment, landscape’s phenomenology has moved from ‘images of landscape’ to ‘embodied acts of landscaping’ [20]. As such, landscape refers to the materialities and sensibilities with which we see, and a broadly vitalist vein could evoke and vivify the material presence of landscape itself, in terms of ‘the incessant elemental and ecological agencies of sky, earth and life’, so that the visual topography of landscape is amenable to reanimation in terms of depth, folding, and actualization [21].

Considering the above, while seeking a significant source of inspiration from Judith Butler’s [22] performativity ethnomethodology, as well as traditions of performance studies in theatre and drama [23,24,25], this article seeks to configure the previous industrial taskscape as ‘stories and dramatic episodes’ [26], with the scene of the organic individual-environment first, then the scene of the organic group-place, the survey on the TSA involves the relations of one single site (the opencast pit) to the greater production network, topology and connectivity of hybrid geographies, which are deployed to sketch out ‘the multiplicity of space-times generated in/by the movements and rhythms of heterogeneous association’ [27] of the urban-rural fringe, while ensuring that a certain topographical richness should not be neglected under the topological complexity. Additionally, the narrative resources from ex-workers and villagers would be creatively recut to craft a style and tone that is close to the events that were remembered in the course of pre-socialist mining construction at the rural terrain, now the urban fringe between the 1960s and 1980s. Based on this, the ‘organic’ history [28] of the industrial past at the urban-rural fringe is thus brought alive due to the interlaced activity trajectories of human and non-human actors, the urban-rural interactions, as well as the materialized fabric of the taskscape in the recollections of former workers.

2. Opencast Pit—The Birthplace of “Southern Oil City”

It is often said locally that without an open cast pit, there would be no Maoming. Our research location, Maoming, the only petrochemical industrial city in Guangdong Province, has long been well-known as “southern oil city”. It is located in the southwest of Guangdong province, south of the Tropic of Cancer and faced with the south sea of china, distinctly features tropical and subtropical marine climate and hilly topography, with abundant heat, sunlight and rainfall most of the year.

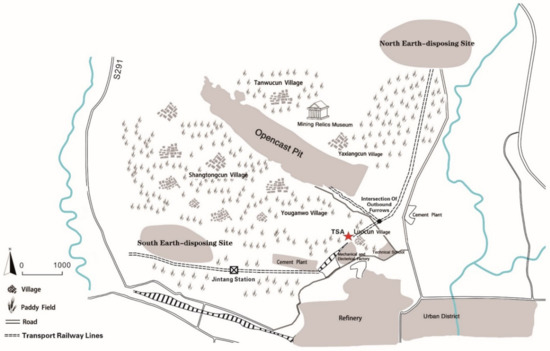

This city was born and grew with the development of oil shale after the founding of new China. When referring to the relationship between the coastal industry and inland industry, MAO Zedong said, “Now we are going to make synthetic oil in Maoming, Guangdong (where there is oil shale), that is heavy industry as well.” Then, the construction of the Maoming shale oil industry, with an annual output of one million tonnes, was included in the country’s first five-year plan, one of 156 key projects. Not long after, in August 1956, approved by the state construction commission, Maoming was officially designated as a petroleum industrial city. Jintang open-pit mining construction broke ground on 3 August 1958, and 8600 people were moved out of 36 villages in the first three years from 1958 to 1960, synchronously, more than 9000 peasants were recruited from seven people’s communes. In the field, the ex-workers told us that the mining process encompass underground water drainage, oil shale perforation, blasting etc., it was equivalent to a battle in search of oil. Though the mining work condition was tough, no one complained. Thus, one saying that if there was no opencast mine, there would be no Maoming has been pervasively popular within this city. Tracing back, it was at an era that the oil production was in scarce supply; to a large extend, open-pit mining had made contributions for the country regarding an effort to shake off the ‘poor oil country’ label and build up its economy. However, with the gradual discovery of domestic oilfields, the development of oil shale projects, which have higher costs and lower oil yields, along with greater pollution, have gradually ceased. The oil shale was officially put into production in 1962 and stopped in January 1993, with accumulated 2.92 million tons of shale crude oil having been given rise to it, the Maoming opencast-pit has mined 102 million tons of oil shale. The pit is not far from the TSA ruin site (see Figure 1), through decades of mining, has become the largest opencast pit in the south of China, with an area of 10.07 square kilometres; the large mining pit lake, with its surrounded areas, constitute the national mining ecological park. Additionally, a new rural construction region of the open pit mine ecological park has been preliminarily formed.

Figure 1.

Map of TSA-in-Maoming (Sources from: The Administrative Committee of Guangdong Maoming High-Tech Industrial Development Zone).

3. Theoretical Perspectives

3.1. Hybrid Geographies

Our attention was first drawn to hybrid geographies and the new biogeographies of entangled nature-cultures [27,29,30] through terms such as network, trajectories, mobility, topological and vitalist geographies to entangle the conventional orderings of human and nonhuman landforms that now seem to be widespread in human geography. It was a burgeoning, proliferating, even wondrous topology in which uncanny and hybrid folds of near and far and past and present emphasise the multiplicity of space-times generated in/by the movements and rhythms of heterogenous association [27]. ‘It is to these entanglements—that comprise what we know as landscape’ [30]. Latour and other actor network theorists are keen on observing the power of things that dwell with us and their power to haunt us (and with them) [31]; however, this approach has its critics [32,33] due to its failure to acknowledge the importance of the place by picturing a flat world within which every object is accorded an equal weight. To counter the limitations, Thrift argues for the ‘non-representational theory’, which is the theory of practices to articulate the ways we might relate ourselves to our surroundings, advocating for the importance of the skilled practices through which we make sense of the lifeworld through our senses and the value of the evocativeness of our strategies of animation [34].

For instance, ‘reintroducing dynamic perspectives and contours into the landscape, as well as texture and feeling, perception and imagination, so elegantly traced by topologies, with something added’ [35], and a new vitalist ‘material imagination’ reimagine both human and ‘non-human materialities as animated by dynamic and lively capacities to affect change and to participate in political life’ [36]. Thus, the hybrid configuration perspective of non-representative theory may help people to understand how people make knowledge of the world, how they physically and socially make the world through the ways they move and mobilize people, objects, information and ideas [37]. As such, the collective trace of our ‘passings’ constitutes to the making and remaking of place.

3.2. Non-Representational Landscape in Memories

In non-representational renderings of the concept, the landscape, like the body, becomes understood as being a variably constituted ‘process’ [38] or ‘event’ [39] that ‘animates’ [35] and is constantly in formation; then, the array of landscaping pioneered by Wylie in the context of specific locales and bodily practices [21,40,41] displays that the visual topography of the landscape is amenable to reanimation in terms of depth, folding, and actualization and is not simply static as ‘an intimacy between the sea and the strand’ [42]. Non-representational geographies are very much about the practice process at the bodily level, which is the same as memory systems at the level of the organism. However, even the grand narratives of collective memories are lived out in the individualised contexts of everyday lives in bodies moving through time-space, which is equated to a ‘mobile spatial field’ [43] while redirecting our attention towards the material compositions and conduct of representations. Lorimer’ s ethnographic reflections are salient in conveying a thick landscape within which ‘poignant personal memoir enlaces productively with the bodily experience of the Cairngorms, and with the knowledge practices of 1950s geography’ [26,44,45] has demonstrated a new form of geographical historiography. As we know, the dynamic visual and tactile senses coming from the movement of the body and the tactile landscaping shift from landscape-as-image to landscape-as-dwelling, which correlates with a substantive shift from the horizon to earth—a ‘grounded performance’. In this way, the landscape begins to merge with the notion of place; landscape and place conjoin intimacy, locality and tactile inhabitation [18]. Newly critical and creative means are suggested to explore the relationships between practices, knowledge, fabric of milieu and locality via re-presenting an original nexus of personal memories (accessed through oral and archival history) and capturing expression ‘in shared experiences, everyday routines, fleeting encounters, embodied movements, practical skills, affective intensities, unexceptional interactions and sensuous dispositions’ [20], which might be an ‘entwined ways of land, life and knowledge’ [44,45].

In this research, the possibility of an array of adjacent workplace spaces arises from the consideration of how each ex-worker’s body mediates, through an assemblage of everyday practices, encounters with hybrid worlds. Through the embodied experiences and practices of mobility, each person generates a situated knowledge. In other words, the tension between presence and distance in landscape engenders the synthetic forces of folding depth by introducing a self-regarding subject (constituted, positioned, and/or constructed in relation to a realised object), and this is supposed to be linked with the conceptualized taskscape, which we will discuss in the following section.

3.3. Taskscape

The term ‘task’ refers any practical operation carried out by a skilled agent in an environment, and every task takes its meaning from its position within an ensemble of tasks, performed in series or in parallel, and usually by many people working together. The concept of the taskscape, proposed by cultural anthropologist Ingold [46], is to the entire ensemble of tasks in their mutual interlocking, which is deployed in this paper to picture the phenomenon of the previous work landscape at the train repair depot and its proximate areas.

Just as the landscape is an array of related features, the taskscape is an array of related activities. And as with the landscape, it is qualitative and heterogeneous; the taskscape is to labour what the landscape is to land. Ingold outlines several core principles or ideal qualities of the taskscape theory. The first programmatic tenet is resonance, which connects closely with movement and rhythm and is intrinsic to the movement itself. It could be argued that in the resonance of movement and feeling stemming from people’s mutually attentive engagement, in shared contexts of practical activity, lies the very foundation of sociality. Second, the taskscape must be populated with beings who are themselves agents and who reciprocally ‘act back’ in the process of dwelling. In other words, the taskscape exists not just as an activity but as interactivity. Additionally, the domain of interactivity should not be only confined to the movements of human beings but includes animals as well. Third, the landscape is the congealed form of the taskscape; the landscape seems to be what we see around us, whereas the taskscape is what we hear. As such, “in reckoning with an environment, we are ‘at my task rather than confronting it’” [47]. Fourth, the pattern of resonances embraces the totality of rhythmic phenomena, whether animate or inanimate. ‘The human body’—Thrift tells us—‘is what it is because of its unparalleled ability to co-evolve with things’ [48]. According to Ingold, ‘life is a name for what is going on in the generative field [49], which is constituted by the totality of organism-environment relations, and the activities of organisms are moments of its unfolding, each form takes shape in continuous relation to those around it, then the distinction between the animate and the inanimate seems to dissolve’ [46].

4. Methods

This study mainly employs qualitative methods of ‘mobile ethnography’ and in-depth interviews, aided by archival and photographic materials. Adopting a ‘snowball’ sampling technique, the potential respondents are introduced by ex-workers (mostly retired), who worked at the industrial ruin site of the TSD (train supply depot) and TMS. Each potential respondent was asked about the type of work and length of service they performed at the industrial relic’s location (see Table 1). As retired workers are mostly elderly with mobility difficulties, there are few opportunities to gather and meet; thus, there is a small number of potential interviewees; they can be contacted by searching for their names or names of others can be provided by them at the spot. Most of the interviewees were contacted through the retired management office of Maoming Sinopec company, a state-owned enterprise, which afforded aid in the inquiry and in search for the interviewed workers according to the list.

Table 1.

Detailed list of interviewees.

Recurrent visits to the open-pit relic, train service area ruins site and nearby villages were provided from 2017 onwards, and during 2018, we made more than 10 visits. Fifteen participants were chosen for the in-depth interviews between July 2017 and September 2019, and the length of each interview is 1.5 or 2 h; the sample comprises two train drivers, two railbus driver, one tea vendor, two workers in TSD and two workers in TMS, four villagers from the rural near the case study site and two other workers, all of which are above 70 years of age. ‘Seated’ interviews and ‘walking’ interviews are the two main forms conducted in the interview activities. In the seated interviews, photographic pictures of the garage relics are used to assist the interviewees in situating the context and anchoring memories. The informal locations of a small community, workers’ homes or the community centre are chosen according to the participants’ convenience and preference. Among them, five interviewees took part in both seated interviews and walking interviews.

It was during the walking process, in which participants were immersed in the surroundings that the profuse narratives were conveyed. Especially, the discursive dimensions of the participants’ experiences and perceptions underlying the narratives are be stressed. Such interactional adaptations and multiple mobilities can create ‘interspaces’—places created on the move, in-between events, in-between origins and destinations [50]. The researcher followed after the elderly worker master while walking, while talking, and learned about the business connection and routine of each locale around the railway paths. Immersed in their ‘lived’ reflexive retrospect, the researcher was alike being brought to the TSA site of the Maoming opencast mining construction era of more than 40 years ago, at the same moment and along the routes under their guidance, attempting to mobilize the sensory experience and move within the networked ruins to imagine and assume the atmosphere in the taskscape in which the human and non-human agents are interwoven at various locales, seeking to describe the fabric of taskscape at ‘transfer points’ (or ‘key actors’) [1] and the dynamic landscape of the mining past around the rails and also the intersecting trajectories that took the initial place to shape the rural-urban fringe.

5. Results & Discussion

5.1. Taskscape of “On-the-Way”

The TSD and TMS were established at the initial stage of open-pit mining in 1958; they are geographically adjacent but belong to different units. The TMS was subordinate to the open-pit mining mechanical and electrical factory, which provided maintenance services for the locomotives (see Figure 2). While the TSD belonged to the open-pit mining locomotive maintenance team, daily, it mainly functioned as the trainmen’s shift room and administrative office, handling the drivers’ reports from the site in parallel to the supply services of adding coal (water) (to the train), testing (the boiler water), boiling (water) and frying sand for the use of the train’s brake. The two sectors featured independent managements but were connected in the business and shared one mission, i.e., to serve trains. In view of the proximity of the geographical locality and of the nature of the work, the case locus in this paper are collectively called TSA (train service area) (see Figure 1). It is the place in between the static and the mobile. the specific movements performed at or around the station, as well as the continuous flow of people, vehicles, and physical resources intersecting through the place.

Figure 2.

Vestige of concrete sleepers at the gate of the garage depot in TMS (photographed by Huasheng Yuan on 20 September 2018).

The TSA and train are like the petrol stations on a highway and cars, except that the latter is on the traffic line and the former is at one end of the traffic network trunk (off-the-way). The TSD workers were divided into three shifts for a 24 h-period. A pre-shift meeting and shift exchange were vital common activities that were frequently mentioned by the interviewees. The shift room was next to the duty room, which can accommodate dozens of people, with spare benches and a blackboard. When time was up, the monitor would call attendance and a meeting was held before the shift, and the shift points were indicated on the board. The pre-shift meeting implied the start of the daily routine work cycle. The rush half-hour gathering interactions embodied the sociality of the shift activities and the monitor’s role as an actor in ‘bonding’ social relations at the spectrum of a fixed place, the TSD.

At the daily pre-shift meeting, the monitor talked about safety items, braking distance before an individual red-light, the shift-hand site of every train, the influence of various construction conditions on the railway, and so on, and he handed over the shift record to the next monitor.(D2)

In the TSD, the monitor, as an overseer, marked down the time of the locomotive pulling in and pulling out, and supervised the driver to inspect the bottom of the vehicle during the phrase of adding water to the coal. D2, an old monitor, reported additional responsibilities and stress for the role of the shift leader (of the night duty) to bear the traffic safety issues, stating the following: ‘you cannot even have a bit relaxation until no accident calls came when the shift was off’.

I held on the whole night and dared not sleep, afraid of criticism and deductions of wages while being caught; that was very troublesome. Sometimes the monitor on duty would call me up to take a walk to be keep me awake.(M1)

What he said was in accordance with D, an old ex-worker on the maintenance team, who stated the following: ‘all of the switchmen’s cabins at the turnout junctions must be checked once on the basis of an uncertain timetable each day to keep the workers, especially those on night shift, from falling asleep.’

The dense movement of vehicles on the railway tracks was characterized as the living landscape of the mining site, and also the ground colour was underlying the narratives of the ex-train drivers.

Delivering the shift record to the next shift was the main engagement at the shift meeting, as the informants mentioned in the following quote: ‘at the time of normal great production, there would have been eight trains and more than a dozen electric trains running back and forth between the pit, the north earth-disposing site and the south earth-disposing site, a maximum of three rounds per eight hours per day, mostly 2′. Then, the rail vehicle stops on the track and waits for the next driver to pick it up (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The pit transport railway line was laid in 1958. Sources from: The Mine Lake Relics Museum.

The monitor knows the locations of the trains on the rails through the dispatcher and assigns drivers to take over at the pre-shift meeting. Drivers get to the trains by rail bus; that’s very troublesome for unfixed sites. In case of railway maintaining or signals failing, the off-work train has to wait on the rail for 2–3 h and the drivers come back the canteen very late.(M2)

In contrast with the continuity commonly shown in the ‘shift exchange’ activity of train traffic in operation, the rhythm for the ‘shift activity’ that took place at the spot among the rail drivers in the opencast mine was an ‘off’, which has been testified by the ex-train drivers. Specifically speaking, you have to seek the spot where the vehicle stops with reference to the memo in the shrift record, which is determined by the exact position of the last driver at the end of the shift. It is obvious that this uncertainty regarding time and place indirectly compressed the length of time that workers spent after work. Furthermore, when the workers arrive at the pit by rail bus, the process of finding this locale to take over is fraught with ‘incessant occurrences’.

In the pit are many high ‘palms’ (mining platforms) 20 to 30 m high that I ever climbed. The shale has been drilled and shaken loose by blast. On rainy days, it’s very difficult to walk on the shale, which is soaked and more slippery. You have to watch out for some fissures in the shale stairs; otherwise, you’d have a fall.(M1)

The body is the basis and conduit of knowledge, and knowledge is forged in movement, ‘in the passage from place to place and the changing horizons along the way’ [46]. As we know, the weather in the south is hot and humid; the pit shaped into a long gradient, from south to north, extending into the underground. The crux is, in the pit, the rock block and clay on each platform were unstable due to the incessant erosion of water and wind; thus, a very instant reaction towards unexpected situations in the work environment is not feasible ‘without the practical knowledge, physical skills, or reflexive reasoning developed by participants through their previous engagement in structure-influenced and structure-influencing institutional projects’ [51].

Regarding the world of work, memory can speak to many types of experiences. However, dramatic events, such as storms, floods or accidents would be unconsciously etched into the depth of the memory. As can be observed from Figure 1, the mining pit is enlaced with the rural areas; the north-south railway tracks extend through the villages. As such, nearby villagers ‘barging in’ the mining workplace realm became commonplace; nevertheless, the path of this kind of intrusion was very irregular, even dangerous. M1, with a dual identity of an indigenous inhabitant and worker of the state-owned enterprise, telling the story in a low and cautious tone, a tone that pervades with shock and regret stated the following:

Some villagers went into the pit to pick up some good shale and take back home. All the good shale was deep under the palm. Once it rained cats and dogs suddenly, someone without a raincoat hid under the palm for cover. The rain burst the shale down and he was hit dead.(M1)

Places are construed as containers for people; then, localized knowledge is seen as containers for the elements of tradition that are passed on to them from their ancestors [52]. Since the shale rock, which could burn oil, was found at large scale in 1945, the mountain in this region was called ‘Huoshui Mountain’ and it has been well identified by the surrounding villagers that shale rock pieces could be used as firewood, and the deeper the shale lay, the better. So, through the twin processes of ‘distillation’ and ‘compartmentalisation’ [53], this knowledge of shales and mines, imparted by the village ancestors, is correct; however, encounters of extreme weather are the exception, such as continuous heavy storm. Thus, this episode might be in accordance with the saying that ‘my body is a thing amongst things, it is caught in the fabric of the world’ [54].

The older workers, with an overly sharp distinction, spoke of the contrast between the work nature at TMS, its neighbour unit, and the vehicle drivers of TSD, especially the train drivers, who had to stay up late, concentrate, and work reverse night and day shifts, which inexorably damaged their health to a great extent. This type of episode, which came from the recollection of the ex-train driver D1, became a ‘dream’ presence haunted in the body, as the following quote exemplifies:

Once, at night, while passing the Jintang station to the south earth-disposing site, I was tired and falling asleep standing. I was dreaming that the train derailed and overturned and suddenly awoke with a jolt, no longer sleepy.(D1)

Point-to-point movement and connection are normal elements constituted in the railway transport landscape (see Figure 4); whereas, for the rail-vehicle driver, in the routine driving, the movement along the trails is a type of wayfaring, a trip moving ‘inward’. To a large extent, the train drivers depend on their powers of vision, a vision in motion. ‘The visible landscape is an ongoing process of intertwining from which my sense of myself as an observing subject emerges’ [42]. Thus, it was the landscape’s visibility in D1’s recollections that emerge as wandering or reassembled due to excessive fatigue and tension.

Figure 4.

14 trunk railways aligned before the Jingtang railway station in 1968. (Sources from: the Mine Lake Relics Museum).

In addition, similar to the different flows of cars in traffic, in the rail transporting milieu, ‘driving speed can be seen as a continuum in which drivers use ‘slow’ and ‘fast’ as relational assessments’ [55] of the way their vehicle on the rails relates to other vehicles.

The rail motor is light and fast. It must follow the signals, stopping at red and moving at green. No matter how fast you drive, the key is that you can critically stop the rail motor in time, especially on a rainy day.(M1)

According to M1, an old experienced rail-bus driver for 20 years, criss-cross railway tracks could be seen from the Jintang station, and the vehicles on the tracks never stopped moving, unless the train was assigned another task. However, there was a short stop, an interspace, from Jintang station when the vehicle passed the boiled water house; this might be interpreted as an indication of its ‘being-on-the-way’, a transit doer rather than a transit resident.

Every train has one or two boiling water buckets. The drivers cook lunch themselves. There’s a platform tied up by sleepers beside the rail to the pit. The driver stops the train on the position of the platform, carrying buckets down for water. When he comes back, another driver helps take the buckets and they drive away.(M1)

Sleepers are the crux materials for railway construction. With an reference to a note in the Picture Chronicles of Maoming Sinopec: “In the year of 1958, the logging camp of Shangyun township was set up in Xinyi, a county under the jurisdiction of Maoming at that time. More than 600 villagers were sent to the remote mountains to cut and collect wood, shouldered and dragged the wood down the mountain to Maoming thusly solved the problem of material for railway sleepers in mine”.

The boiled water house was located between the Jintang station and the intersection of the ‘outbound furrows’, the trunk lines. After this intersection, the train headed for the pit or the earth-disposing site. The task of filling water was so significant because it prepared the train crew on the railway with the raw material used for drinking and making steamed rice throughout that day. At the ethnographical site, we learn that the boiling water house is not far from the TMS, a square house equipped with two large woks and stoves, with burning coal to boil water. Prior to the shift exchange, the workers on duty, would walk the trails to the coal yard of the TSD to fill dustpans with coal and return to the square house, ready for the next shift. Mesh-like trajectories around the boiled water house and TSA area reflect the connection between the TSA, the pit and other lines of the production mesh, as well as the material loop with a focus on coal.

Here, one case is when the train is out at work and is unexpectedly in urgent need of coal and water; it would sound the horns in advance, a well-known language; in this way, the driver conveys this message to the nearest switchman’s cabin.

Three long horns for adding water, three long followed by two short horns for adding coal. The switchman reports to the dispatcher to adjust the train route. The driver puts a ruler into the tank to plumb the depth of water and decides when to add water. While the fireman suggests whether to add coal.(D1)

From the above, precisely knowing the time to fill the train with coal and water, viewed as first-hand knowledge, comes from the process of unfolding differentiation, but is finally acquired through becoming in tune with the landscape. More, long horns and short horns are a non-representational type of language and are presented in a rhythmic way; when encountering fast flows and discontinuities moving around in his environment, the worker actor, by watching, listening and feeling, actively seeking out the signs by which it is revealed [31].

5.2. Urban-Rural Intersection: Interweaving Human and Non-Human Movements

The TSA site is adjacent to Luo village. Those old enough in the village still remember the TMS area where the workers repaired the vehicles; various vehicles with fully loaded materials were being aligned on the railway track for entrance into the 2nd warehouse. Nevertheless, just as Edensor [56] observes in his analysis of urban industrial ruins, although ‘vacant’ and unregulated, this particular site came to offer a space for unofficial activities and everyday practices, such as ox herding and pasture rearing chickens (see Figure 5). In the same vein, it served as an unofficial playground for children of Luo village and, consequently, was featured repeatedly in interviewees’ accounts of their childhood memories, as follows:

Figure 5.

Hybrid landscape at the urban-rural fringe (photographed by Huasheng Yuan on 5 August 2019).

At that time, the train repair shop was the children’s paradise. It had no bounding wall and we went in and out at will, often playing hide-and-seek and stone fights nearby. At night, the flagmen took us to the pit to play, swinging the flags, changing the light’s colour to give signals.(W5)

Sometimes I went to the coal yard to pick up some wood and broken coal for back home. The men on duty at the coal yard didn’t pay much attention to me since we met often. (No barbed fence and bounding wall).(V1)

The villagers’ accounts manifested a resonant rhythm themed with free, informal and harmonious interactions between the rural children and the TSD industrial heritage site. Flickering flags and illuminating lights were simple entertainment elements that were embedded into the transporting taskscape and industrial sites and had enlivened and enriched the out-door recreational activities of rural children under the background of that poor economic era. It is at this point that the village’s history intertwines with living memories of events that occurred within the landscape, both past and present. According to V1, a long-term resident of Luo village, the land needed to be expropriated by the opencast mining company for the use of mine construction; as compensation, the young and middle-aged people in the village were allowed to be enrolled into the Maoming Sinopec as temporary employees and converted into urban residents in 1969, along with the admission for their children to stay and work in Sinopec because of the status of workers; even in 1962, the salient difficult period of the state, villagers did not have to turn in public grain while gained food was assigned by the state, which was rarely seen at that time. Those participants who had family members that had worked in the Maoming Sinopec or its associated industries talked proudly of this connection and related stories that their parents or other community members had told them about life during that era.

In about the 1960s, the pit embodied Luocun village as a ‘sideline team’, exclusively supplying food, vegetables to the families of the miners. My father was the production team leader at that time. Together with several other people in the village, he sent coal to the families with a wooden cart. They got along well with each other.(V1)

At that time, life was so hard that we cleared wasteland to grow vegetables on our own. My father found a plot of land used to store coal cinder over the coal yard, and he ploughed the land, spread soil on the surface and grew vegetables by water passing through the TMS drain.(V2)

As shown above, the villagers’ everyday life trajectories intersecting with the materialized localities of the TSD heritage site was created out of the binary relations of the train depot-playground and the coal field-vegetable field; additionally, the symbol connecting their equivalent which is respectively manifested as fragmented coal to firewood and flags to toys, imply that close-knit relationships formed between the rural and the heritage site, agriculture and industry. The data features the integration of agriculture and industry in the development history of Luo village. The Luo village and the TSD site were blessed with geographical proximity (proximity) and proximity of institutional and social relations [53]. Such an interaction of ‘no walls and no barriers’ accelerates the process of rural urbanization in this area.

The theme of urban and rural interactions emerging out of the recollections of the Maoming opencast mine are multifaceted and layered. Workers at the train repair depot mostly came from nearby villages and towns. They had one day off every week and had to work overtime if any train broke down on Sunday. W1, who was an old leader of the TMS station, recalled his return to his hometown village, Sishui town of Gaozhou county in the 1960s as follows: ‘it is awfully hard, continuously walking for 3–4 h without breaks until the 1970s, when bicycle is available, paying a bicycle guy a few cents for a lift to Fenjie town first and walking home’. Nevertheless, for some poorer workers from the rural, temporary or longer-term migration may be the only way to get away from the harshness of local forms of agricultural employment or from material poverty [57]. However, there are some commonalities and continuities worth drawing attention to the urban-rural movement. Agriculture is very often seasonal, this seasonality makes for an uneven demand for labour forces in tasks such as ploughing, planting, weeding and harvesting.

In the year of 1981 or 1982, amid the reform and opening up, the country distributed farmland to households. My family needed to farm rice, but I couldn’t come home in daylight in the farming season. I had to come home at night and finished raking and ploughing the fields so that my wife could plant rice seedlings the next day, she was very hard.(W2)

Numerous routes, which stretched out from each starting point and ending with every destination had shaped network-like social relations, hence, forming the embryonic form of the city. Those workers arrived home at night and became farmers; informal labouring is a characteristic of the rural and seasonal physical demands; from another aspect, as they move, agricultural workers literally produce space to obtain livelihood resources from both rural and urban areas and complement each other to seek the double benefit of agriculture and the city and avoid the risk of uncertainty. After the reform and opening up, facilitated by the structure of the market economy, depot workers were also found occasionally doing part-time small business, as old worker W1 stated in the following quote:

In the slack seasons, some workers had small businesses in private. They came back to their villages and brought sweet potato, taro and corn from home on Saturday evening, and they cooked those and sold them in urban areas on Sunday. They together sold fruits, such as litchi, longan and jackfruit, yielded by their families. As they sold out, the workers returned back to the factory on Monday.(W1)

This circular or ‘spiral’ flow of migrants to and from the mining centres brought about the two-way track of the urban-rural element flow, where working the schedule of the factory resonates with the growth speed of rural crops and the phenomenon of day-night cycles, which is distinctly reflected in the interwoven human landscape of workers, peasants, urban and rural areas in south China during the pre-socialist industrial construction period from the 1960s to the 1980s.

In addition to the movement of workers to and from their home villages, B1, a flowing tea vendor, together with his Xindong tea, ‘unconsciously’ intruded into the mining area.

I live in Jinshan town and carry on trade in tea for 30 years. I often went to the strip mine to sell before. Many workers were there. I went once every two days and I did business for 20 days in a month. Initially, I rode a bike for over an hour to the mining team, dump team and traffic team, anywhere there was a way to.(B1)

Movement is itself the tea vendor’s way of knowing, and his wayfaring yields an integrated, practical understanding of the lifeworld. In the course, ‘some memory of the journey will remain, however attenuated, and will, in turn, condition his knowledge of the place’ [58]. As an outsider from the peripheral countryside, tea was taken as an intermediary; the old villager G entered the official workplace of the national mining enterprise by virtue of informal walking; hence, he was connected with the workers at the sectors of the TSA area, the mining pit, etc.; thus, the social network of informal tea sales in the mining area consequently came into being. The experiences nevertheless remain embedded in his memories and identification of the opencast mining area.

I’d been to the mechanical and electrical factory, which had several job teams with more than ten fellows each. They got five to six bags of tea every time. They like Xindong tea. My tea is fresh and never mixed with aged tea. They said they had fewer colds after drinking my tea. The workers doing hard work bought some more. Those of laying railway, switching railway, checking railway were exposed to the sun and they wet their whistles by drinking tea. The office people also drunk my tea while they bought that more expensive.(B1)

Tea is a so called ‘inanimate’ thing with a ‘mysterious effect’ [56]; it changes people and circumstances, and it changes different people in different ways, according to the differences in the types of work, gender, class and being native or non-native. Boiler water analyst L recalled her encounters with tea as follows:

People of the duty room cleaned up waste coal cinders in the coal yard and sold them at intervals. Some money was kept as the team’s expense, the extra would be given to the workers. The monitor cost 4 or 5 Yuan to buy a package of Xindong tea and invited the drivers to drink. He made a pot of tea and the room was full of the fragrance of tea.(B1)

The train and motorcycle drivers, who had spent most of the day running along the tracks before going to the duty room for the supply of coal and water, were generally imbued with coal ash and fatigue on their faces, and the tea’s light flavour kept them temporarily from facing the oncoming hot wave arising from sending coal into the train furnaces, as well as from the grime of working with machinery thus endowed with agency. As such, serving as one appealing thing, tea had animated the atmosphere of and prompted the interactions that occurred in the office room, thus achieving the harmony of the TSD depot.

However, for the TMS sector, which is only separated by a ‘wall’ with the TSD, the activity of drinking tea is a symbol of custom and the status of the old master. At the site of the ruins, W2, an old leader of this section, took a deep sip of Xindong tea from a glass bottle he had brought with him, stating the following:

After 1980, every team had bought their own tea set. The old master went to work early and got to the team room at ten past seven. He made tea and tasted it for a while, then had a smoke until time for roll call and the pre-shift meeting.(W2)

Part of the embeddedness into the process of labouring is through mundane habit and custom. We argued that a work identity for both individuals and work groups was formed out of this type of collective and produced a ‘structure of feeling’ of a particular type [59]. Williams talked about structure of feeling as being understood as emergent, dominant or residual. Tea, as a common object, that emerge and embodies the structures constitutive of a particular type of workplace environment, that have the same meaning for a given set of workers who are recruited at different times and are seen in the same manner by them. This is the sense in which workers are, and feel able to be, deeply embedded within work. The cumulative experiences in a given setting can create complex, multi-layered meanings, as previous meanings are taken into account and then connected to an individual’s own experiences to form their feelings of a site, as well as a shared understanding of collective identity. W2’s habitus of drinking Xindong tea represents a movement from the externality of established customs and norms to the internality of durable dispositions, in this way, Xindong tea conjures up a sense of past people and past times, of customs, beliefs and localism.

A total of 17 railway trunk lines, with the Jintang terminus as the main parking spot for open-pit mining vehicles, extending in all directions through dozens of stations of various scales, mainly comprising the mining pit, the earth-disposing sites in the south and north, etc. Moreover, these stations are located in or near the rural areas adjacent to the mining activity, including the villages under the jurisdiction of the towns of Jintang and Gongguan. Consequently, urban-rural personnel exchanges were strengthened along the rail tracks. This is consistent with the testimony of M1, the driver of the railway car, who said that in addition to the mine workers, there are also many villagers hitchhiking home. The clustering of human flow, material and energy flow has brought about the appearance of built landscapes, such as other service facilities and institutions. That is why we say, ‘the advent of the opencast pit first, then the Maoming city’, in this case, the rural area near the TSD site had realized the local urbanization earlier because of the open-pit mining.

6. Conclusions

The depth and richness of the memories of the industrial ruin site and the memories of industrial remains demand the attentive empathy of the researcher to dig, recover and rescue. To seek the man-land relationship implied in the articulations of industrial networked ruins between the multiple scales, we need to explore places as ‘constructed out of a particular constellation of social relations, meeting and weaving together at a particular locus’ [60] and persistently highlight the wider relations of even the smallest geographies. To anchor this aim, a topology and connectivity of hybrid geographies is applied in sketching out the multiplicity and temporality of the landscape generated in/by the movements and rhythms of the heterogeneous association of the urban-rural fringe. However, to prevent the view of ‘a flat picture’, ‘certain elements of this could be usefully drawn into the non-representational milieu to ensure that this fundamental aspect of life’ [61] is more fully accounted for. Mobility can be reflected from the movement and be employed as one of perspectives to evoke the memories, especially regarding the relevant sense of motion-in-vision and tactile engagement in driving and walking, such as the transport landscaping of ‘on the way’. Ingold’s taskscape conceptualized terms penetrate into this paper to explore the phenomenological industrial past in memories. In the first scene, the landscape as interlocking cycles and rhythms is brought to life in some episodes, combining ongoing incessant storms, the dense movement of vehicles on the railway tracks, rhythmical horn sounds in the air, solely but significant short stops near the ‘outbound furrows’, extremely slippery shale with fissures, where elsewhere, a ‘wayfarer’ is carrying coal with dustpans on the trails.

In the end, the landscape of the industrial past turns animated along the organism’s movement. The participant’s dual identity as both a mining worker and a native lends weight to the urban-rural dimension and the spill over of indigenous knowledge; this is spontaneously parallel to the heterogeneity of the hybrid industrial-rural landscape between the 1960s and 1970s. in the second scene, the grand historical background of the country and of the region were reflected distinctly or indistinctly underneath the small stories. The urban-rural intersection featured multifaceted and layered topological geographies; specifically, the temporary or longer term movement between the workplace and other rural areas (worker’s home village), which is endowed with rurality and seasonality, brought about the two-way track of the urban-rural element flow, yet produced space to balance the gap between the urban and the rural. Nevertheless, it was surprising to see a flowing tea vendor, loaded with his Xindong tea, slowly but nimbly emerge on the trails distributed at the peripheral mining areas, like a jumping tune, barging in visual sights of the people there. Here, tea, akin to a fluttering arc, conjured up a sense of past people and past times, of customs, beliefs and localism. The data show that the Luocun village and the TSD site were blessed with geographical proximity and proximity of institutional and social relations [62]. Such an interaction of ‘no walls and no barriers’ accelerates the process of rural urbanization in this area. Rural geographers argue that the recognition of the network space, which is characterized by multiple factor flows and their dependence relation connecting urban and rural nodes, will lead to the end of the urban-rural dichotomy [63]. As such, the better we trace the complex web of former connections, the more material we have to argue for hybrid networks of nature/culture when revitalizing the landscape.

As for our research, in particular the second scene, taskscape was put under the broad context of social history to demonstrate the intersecting effect on the urban-rural border area and its affordance while consistently at its crux which is enlaced with movement, memory and place, has amplified to some extend in contrast with its basic principle of ‘organism-environment’. Our visits were obviously limited by time, resources and opportunity, what we have exploration only a portion towards non-representative theory-a vast and elusive theoretical system pervasive with vitality. As for our research, in particular the second scene, taskscape was put under the broad context of social history to demonstrate the intersecting effect on the urban-rural border area and its affordance while consistently at its crux which is enlaced with movement, memory and place, has expanded its length on principle of ‘organism-environment’. Our visits were obviously limited by time, resources and opportunity, what we have explored only a portion towards non-representative theory-a vast and elusive theoretical system pervasive with vitality. From the perspective of post-phenomenology of new cultural geography, the study of industrial geography can revivify the dead geography and answer the complex queries in the study of the working-class. Correlative future studies could expand to the connection between modern industrial development and industrial past, as well as industrial material and environment.

Paper chime with broader critical geographical concerns on accelerating processes of economic restructuring and selective destruction, on the rural livelihood and city development. the paper’s considerations on evoking the memories of the industrial past has bridged between the representational and structural and the non-representational, the phenomenological and the post-structural, and on heeding a closeness to the style and tone in which events are organized as dramatic episodes, might be regarded as an innovation of the same type. The ethnography at the TSA industrial ruins site has proved to be encounter with a world that is thick with the significance inscribed by the memories of those who have previously lived within it. One quotation thought of at this instant may situate this right: ‘It is its soul. I mean if people, even this generation, if they found out... how the place came into being and how hard people fought for it to become what it is, they would have a greater appreciation of the town and its ideas’ [64].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Y. and J.L.; methodology, H.Y.; software, X.C.; validation, H.Y. and D.Y.; formal analysis, H.Y.; investigation, H.Y.; resources, H.Y.; data curation, H.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, H.Y., D.Y. and X.C.; visualization, H.Y.; supervision, D.Y.; project administration, D.Y.; funding acquisition, D.Y. and X.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant numbers 41901173, 41971184], the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019M662835) and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018b030312004).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sears, J.F. Sacred Places: American Tourist Attractions in the Nineteenth Century; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mah, A. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, R. Mining memories in a rural community: Landscape, temporality and place identity. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 36, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, A.; Piper, I.; Fern’andez, R. The study of memory sites through a dialogical accompaniment interactive group method: A research note. Qual. Res. 2014, 14, 712–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O. An ecology of emotion, memory, self and landscape. In Emotional Geographies; Davidson, J., Bondi, L., Smith, M., Eds.; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2005; pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, L. Encounters with haunted industrial workplaces and emotions of loss: Class-related senses of place within the memories of metalworkers. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 20, 467–483. [Google Scholar]

- Palus, M.; Shackel, P.A. They Worked Regular: Craft, Labor, and Family in the Industrial Community of Virginius Island; University of Tennessee Press: Knoxville, YN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Samuel, R. Theatres of Memory; Verso: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Qviström, M. Network ruins and green structure development: An attempt to trace relational spaces of a railway ruin. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrift, N. Afterwords. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2001, 18, 213–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrift, N.; Dewsbury, J.D. Dead geographies and how to make them live. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2000, 18, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenning, A. For working class geographies. Antipode 2008, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Mundane hauntings: Commuting through the phantasmagoric working-class spaces of Manchester, England. Cult. Geogr. 2008, 15, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L. Archaeologies and geographies of the post-industrial past: Landscape, memory and the spectral. Cult. Geogr. 2013, 20, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Garde-Hansen, J. Introduction. In Geography and Memory: Explorations in Identity; Jones, O., Garde-Hansen, J., Eds.; Palgrave-Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, J. Gilles Deleuze: Vitalism and Multiplicity; Pluto Press: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Whatmore, S. Materialist returns: Practising cultural geography in and for a more-than-human world. Cult. Geogr. 2006, 13, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J. Landscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Rethinking the animate, re-animating thought. Ethnos 2006, 71, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, H. Cultural geography: The busyness of being ‘more-than-representational’. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2005, 29, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J. Depths and folds: On landscape and the gazing subject. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2006, 24, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex; Routledge: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Dewsbury, J.-D. Performativity and the event: Enacting a philosophy of difference. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2000, 18, 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Cormack, D. A paper with an interest in rhythm. Geoforum 2002, 33, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mc Cormack, D. An event of geographical ethics in spaces of affect. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2003, 28, 458–508. [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, H. Herding memories of humans and animals. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2006, 24, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatmore, S. Hybrid Geographies: Natures Cultures Spaces; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mels, T. Nature, home, and scenery: The official spatialities of Swedish national parks. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2002, 20, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhough, B.; Roe, E. Towards a geography of bodily biotechnologies. Environ. Plan. A 2006, 38, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pile, S.; Harrison, P.; Thrift, N. Patterned Ground; Reaktion: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. Steps to an Ecology of Place. In Human Geography Today; Massey, D., Allen, J., Sarre, P., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, N. False antithesis? Marxism, nature and actor networks. Antipode 2002, 34, 111–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whatmore, S. Hybrid Geographies: Rethinking the Human in Human Geography. In Human Geography Today; Massey, D., Allen, J., Sarre, P., Eds.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller, P. Sensuous Scholarship; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, M.; Wylie, J. Animating landscape. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2006, 24, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson-Ngwenya, P. Performing a more-than-human material imagination during fieldwork. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 21, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bscher, M.; Urry, J. Mobile methods and the empirical. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2009, 12, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M. Landscape and labyrinths. Geoforum 2002, 33, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Landscape as provocation. J. Mater. Cult. 2006, 11, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J. An essay on ascending Glastonbury Tor. Geoforum 2002, 33, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, J. A single day’s walking: Narrating self and landscape on the south west coast path. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2005, 30, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The Visible and the Invisible; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, N. Excluded spaces: The figure in the Australian aboriginal landscape. Crit. Inq. 1996, 22, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, H. Telling small stories: Spaces of knowledge and the practice of geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2003, 28, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, H. The geographical field course as active archive. Cult. Geogr. 2003, 10, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill; Routledge: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Routledge: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. An anthropologist looks at biology. Man 1990, 25, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, M.; Truch, A. The Role of Interspace in Sustaining Identity. In Thumb Culture: The Meaning of Mobile Phones for Society; Glotz, P., Berscht, S., Locke, C., Eds.; Transaction Books: New Brunswick, NJ, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pred, A. Place as historically contingent process: Structuration and the time-geography of becoming places. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1984, 74, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingold, T.; Kurttila, T. Perceiving the environment in Finnish Lapland. Body Soc. 2000, 6, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadasdy, P. The politics of TEK: Power and the integration of knowledge. Arct. Anthropol. 1999, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Humanism and Terror; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Laurier, E. Doing office work on the motorway. Theory Cult. Soc. 2004, 21, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. The ghosts of industrial ruins: Ordering and disordering memory in excessive space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2005, 23, 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. Limits to Capital, revised ed.; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Being Alive; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, R. Marxism and Literature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D. A global sense of place. Marx. Today 1991, 6, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, O. Geography, memory and non-representational geographies. Geogr. Compass 2011, 5, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.S. Proximity, embeddedness and evolution: The role of networks in the development of the informal female labour market for glove manufacturing in Gaozhou county, China. J. Rural Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.L.; Zhang, X.N. Progress in international rural geography research since the turn of the new millennium and some implications. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, K.; Eklund, E.; Reeves, A.; Scates, B.; Peel, V. Broken Hill: Rethinking the significance of the material culture and intangible heritage of the Australian labour movement. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 4, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).