Abstract

The first career interest inventory emerged in the late 1920s. The response options for the questions in the Strong Vocational Interest Blank included ‘like’ and ‘dislike.’ Both answers are emotional reactions. Regrettably, clients within the context of vocational counseling often regard negative feelings (e.g., dislikes) as inconsequential. Yet, negative emotionality can be adaptive and feasibly assist career decision-makers. In the literature on college students’ career development and emotional functioning, there is a paucity of information about how negative emotions advance the career decision-making process and how career decision-makers apply such knowledge. Hence, a sample of undergraduates (n = 256) was recruited to ascertain imaginable adaptive career decision-making benefits from negative affect. Employing a Mixed Methods-Grounded Theory methodology, the present study tabulated the negative emotional reactions of college students to vocations that were self- or computer-reported. In addition, their answers to two investigative questions about the selection of their negative emotions were analyzed. From the data, three negative meta-emotions emerged as reactions to participants’ reported occupations; four adaptive purposes for their selected negative affect were also discovered. A theoretical framework and applicative suggestions from the findings are presented.

1. Introduction

In 1909, a book by Frank Parsons stressing the importance of vocational preparedness was published. He argued, “It is better to sail with compass and chart than to drift into an occupation [haphazardly] or by chance or uninformed selection” [1] (p. 101). Eighteen years later, E. K. Strong published the first career interest inventory [2]; he designed it to assist people’s preparation for entering the world of work. In the Strong Vocational Interest Blank, career decision-makers were asked questions about their preferences for vocations, tasks, and activities. Response options included ‘like’ and dislike’ [2]. Both answers are emotional responses; in particular, the latter alternative, ‘dislike’, is an aversive reaction or a feeling of disapproval [3].

Within the context of vocational counseling appointments, clients often consider negative feelings (e.g., dislike) toward vocational selections as inconsequential. Regrettably, by doing so, they discount the significance of the affect and overlook an important source of information. In contrast, emotion scientists maintain negative emotionality is adaptive and underscores important needs related to human wellness [4]. For instance, Hess and Parrott specified that negative affect could promote cooperative living, prompt social problem solving, and signal important personal values and life priorities [5].

If career decision-makers did not dismiss their ‘dislike’ responses and instead, continued exploration, what would they discover? In other words, clients pause, venture behind a ‘dislike’, and examine the rationales undergirding the negative emotionality. Would adaptive information emerge from their responses to career options? Can this knowledge benefit or even advance a selection process? If so, how might career specialists assist people in being ‘vocationally prepared’ by their negative affective information?

The following seeks to respond to the aforementioned inquiries. We explicate the adaptive purposes of negative emotion and current findings about the role of emotionality within a career development context. Outcomes from mixed methods analyses of the answers offered by undergraduates to inquiries about their negative emotive reactions are presented. Moreover, we offer a theoretical framework enlarging the role for emotionality (i.e., negative) in the context of career decision-making and applicative suggestions relative to our findings.

1.1. Adaptive Purposes for Negative Emotions

Negative emotions tend to be widely misunderstood. Although negative feelings have always been around [4], some people gravitate to the myth that negative feelings are inherently bad [6] and expression of these affects make them unpopular and others uncomfortable [7]. Ironically, the English language contains more negative emotive words than positive ones [8].

Evidence for the important utility of negative emotions is growing. Greenberg concluded that successful adaptation is predicated on the awareness, toleration, and regulation of negative affect [9]. Graham et al. reported beneficial outcomes from the expression of negative affect [7]. Such self-disclosures positively correlated to the quantity of social ties, intimacy between close friends, and self-esteem. Baker, McNulty, and Overall noted that people who express negative emotion are often conveying their needs to significant others [10]; this, in turn can elicit help and increase others liking them.

Hess and Parrott identified rationales on how negative emotions contribute to personal fitness, helping people pursue opportunity and avoid misfortune [5,11]. First, negative affect promotes cooperative living. Moral emotions such as contempt and disgust (i.e., other-condemning feelings) along with guilt and embarrassment (i.e., self-conscious affect) motivate people to pursue altruistic actions and confront moral violators. For instance, cheaters tend to take more than they give; cooperation requires reciprocity. The lack of, or limited, reciprocity undercuts a spirit of collaboration [12,13]. Guilt can prompt people to make amends for the wrong done (e.g., cheating) or even motivate them to avoid cheating altogether. Disgust can prompt individuals (e.g., the cheated) to take steps to rectify the reciprocity imbalance. Second, certain negative emotions reduce social apathy and enhance social problem solving [14,15]. For example, anger is often a response to an injustice. This affect can motive people to defend themselves and others along with taking productive steps to redress the wrong and/or remove the threat. Third, negative feelings vocalize people’s values and priorities in life. Sadness is often a reaction to some loss. Feeling sad or experiencing grief over the loss of a parent signals the rich relational connection that existed when the person was still living.

Johnson and Connelly reported positive associations between the emotional displays of people who provide feedback (providers) and the emotional displays of individuals receiving feedback (recipients) during an evaluative meeting [16]. When providers displayed anger in their feedback, recipients exhibited high levels of anger. When providers displayed disappointment in their feedback message, recipients tended to experience guilt. Moreover, providers’ display of disappointment resulted in prosocial behavior by the recipient indicating positive organizational outcomes with negative emotions.

Last, Coifman, Flynn, and Pinto investigated the relationship between negative emotions and psychological health and adjustment [17]. With a sample comprised of undergraduates and adults, they indicated negative affect (i.e., fear, sadness, guilt, anger, and disgust) related to better relational adjustment, higher treatment compliance, and healthy reactions to peer rejection. The authors demonstrated the adaptive utility of negative feelings in specific contexts—intimate relationships, chronic illness, and college adjustment across two age-related populations.

1.2. Emotion in the Career Decision-Making Process

Emotion plays an important role in career choice. Emmerling’s qualitative study with decision-makers discussed several findings and hypotheses pertaining to emotional functioning within the career decision-making process (CDM) [18,19]. First, discovery of career interests involves the emotional memory bank. Emotion scientists have identified emotion playing an important role in the memory processes of encoding, storage, and retrieval of information [20]. Salient personal events and experiences, constructed and reconstructed ones, are stored in long-term memory—particularly, the autobiographical memory system (AMS) or the ‘remembered self’ located in the hippocampus [21,22]. When people answer questions in a career interest inventory, they are most likely retrieving life experiences in the AMS. Their answers are judgments on vocation-related likes, dislikes, activities, and values prompted by past life events, people, and associated affect. Furthermore, arousal levels are important factors when individuals engage a vocational assessment. For instance, respondents experiencing intense anxiety, a high autonomic arousal state, will most likely have diminished working memory capacity; they will experience retrieval difficulties and struggle selecting response options to questions [23,24].

Second, emotion can facilitate or hinder self-exploration, which is considered the skill of reflection or introspection leading to increased personal insight on occupational phenomena. Emmerling expected affect to influence decision-makers’ level of self-awareness [18]. For instance, positive feelings often correlate with low defensiveness. When individuals are less sensitive to exposed weaknesses, they tend to make self-judgments that are more accurate and avoid foreclosed decisions.

Third, feelings influence risk assessments or choice-riskiness. This particular task in CDM denotes people calculating possible pleasant or unpleasant expectations (e.g., geographical re-location) when selecting a career or making an occupational-related decision. For example, individuals are expected to make fewer risky decisions with high levels of positive affectivity; likewise, low levels of some negative emotionality (i.e., fear) perceive greater risks or select more ‘sure’ alternatives [25,26]. Yet, high levels of other negative affect tend to evoke increased risk-seeking choices; anger activates lower risk estimates [25].

Fourth, emotions influence a sense of agency—the ability to make career choices based on personal preferences and then, assume responsibility for decisions [27]. Emmerling maintained that peoples’ assertion of agency means vocational pursuits are based on their preferences and self-awareness [18]. Greater dependence on personal insight was hypothesized to correlate with higher job satisfaction, a positive feeling. Regarding these kinds of judgments (i.e., occupational choices), Lerner and Keltner discovered individuals who are more fearful tend to make pessimistic conclusions, while those who tend to be angrier make optimistic conclusions [26].

Fifth, emotion can also sway decision-making style, the manner in which people make choices about occupations. Positive affectivity was expected to prime a conceptual style of decision-making [28]. People would rely on intuition or gut-feelings and think more globally in their decisions; they are prone to produce more creative solutions [25]. For instance, happiness can be associated with a sense of certainty leading individuals to embrace a heuristic-intuitive style; they are less likely to focus on details [29]. Nevertheless, there are limitations to positive moods. Pham contended that positive emotionality could prompt people to over-rely on global knowledge sources such as stereotypes [24]. Furthermore, with negative affectivity, there are varied decision-making styles. For example, anger and disgust also prompt a heuristic-intuitive style; sadness and fear trigger a systematic-deliberative style [24,29].

Last, thirty years ago, Loman encouraged career counselors to understand and attend to the varied emotional dimensions associated with vocational concerns [30]. Emotions often emerge prior to cognition and can operate as a therapeutic compass revealing unmet needs [31]. As active information-processers, people weave together material from multiple sources (i.e., affective, cognitive) [32]. This on-going synthetic effort potentially leads to a comprehensible account of their ‘self-stories’ [33]. Optimal functioning occurs when individuals weave together all known sources of information—not consciously or unconsciously blocking out any particular resource [34]. Hence, Emmerling’s creative and insightful thinking about the place for emotion within career development inspire vocational specialists seeking a holistic approach [18,35].

1.3. A Literature Review of Negative Emotions and the Career Decision-Making Process

Within vocational psychology, only a few lines of inquiry theoretically and empirically explore the relationship between negative emotions and career phenomena. Researchers have speculated about beneficial possibilities with negative feelings in the career decision-making process (CDM). They also have established the detrimental outcomes with high levels of negative feelings in the CDM journey and reported observational data on the kinds of negative affect in CDM.

Concerning beneficial possibilities, Emmerling delineated adaptive purposes of negative emotions anticipated for the CDM process [18]. Negative affect (NA) alerts people to current difficulties within the status-quo needing change [36]. This awareness can potentially motivate individuals to seek assistance. Some NA (e.g., fear) prompts a gradual and detailed processing style. This kind of information-processing approach emphasizes accuracy [4]. Emmerling also predicted benefits for risk assessment and decision-making style. Some NA was expected to incline people to be risk averse and more careful decision-makers. For instance, low to moderate levels of NA (e.g., sadness) often prepare individuals for a deliberative decision-making style, one that is “rational, logical, and planful” [18] (p. 46). These possible contributions of negative emotionality can expand career decision-makers’ knowledge base. Yet, Emmerling’s propositions await further empirical verification.

Regarding deleterious effects, Hardin, Varghese, Tran, and Carlson discovered an inverse relationship between social anxiety and occupational commitment [37]. Lent, Ezeofor, Morrison, Penn, and Ireland indicated decisional anxiety negatively related to decisional self-efficacy [38]. Connolly and Viswesvaran concluded that negative affect (NA) was correlated to job dissatisfaction [39]. Similarly, Kaplan, Bradley, Luchman, and Haynes stated NA was negatively associated to job performance (e.g., withdrawal tendencies, injuries on the job, and distracting work behavior) [40]. Rector found stress and worry as one of the four factors underlying career indecision and Vignoli reported general trait anxiety and career anxiety positively associated with career indecision of adolescents [41,42]. Last, Emmerling hypothesized that high levels of NA would associate with impulsive decisions, restricted attention, higher defensiveness, and limited self-exploration [18].

For observational data, Young, Paseluikho, and Valach investigated the kinds of emotion evoked in conversations between parents and their adolescents about career preferences and employment qualifications for the latter [43]. In this qualitative study, positive and negative affect emerged in several exchanges. Two notable patterns transpired with negative feelings. When ‘rival goals’ (i.e., dissimilar choices) led to an impasse in the discussion, negative affect was triggered. For instance, a daughter became angry and chose to stop talking to her mother; the mother worried about how much advice the daughter needs to keep hearing. When a parent or youth referenced ‘undesirable’ occupations, they described the options as scary, boring, not exciting, and not fun. Puffer replicated parts of the project by Young et al. [44]. He cataloged the frequency of emotional reactions (i.e., positive and negative) by undergraduates while they reviewed assigned occupations. Using an 18-emotion checklist (i.e., the State Affect Checklist), 35% of the 40,000 emotional responses were negative ones (e.g., tedium, bland, anxiety). Puffer also discovered more negative emotional reactions to vocations from computer-generated options (37%) transpired relative to self-reported careers (25%) [44].

Convincingly, there is sufficient evidence and hypotheses explicating how high levels of negative emotionality (i.e., fear) distract and inhibit career development [45]. The qualitative research investigations make plain the different kinds of negative affect, beyond fear, emerging in the career decision-making journey. We also know how often certain negative emotions were elicited and under what conditions they emerged. However, several facets of negative emotions’ relationship with CDM remain unclear. Are the findings on the kinds and frequency of negative affect replicable? Would replication help confirm the accessibility of emotion in the CDM process? Further, the information from the categorization and incidence of affect prompt questions such as why the decision-makers identified the specific negative emotions and how affect assists them in the career decision-making process.

Insight from career decision-makers’ emotional worlds may offer appropriate answers to the aforementioned ambiguities in the research literature. Therefore, the present study pursued the following two research questions.

- Can the kinds of negative emotions and their frequency discovered in the studies by Young et al. and Puffer be confirmed [43,44]? Further, can the differences between the kinds of negative emotional reactions aroused from self- and computer-reported occupations be established again?

- ○

- These quantitative-oriented queries prompt another check of the replicative nature of the observational findings of Young et al. and Puffer. Both could confirm the accessibility of emotional data in CDM.

- Why did the participants select the negative emotions and what purposes did the affect serve them as they processed the merits of vocational options?

- ○

- These qualitative-oriented probes go beyond the observations of Young et al. and the frequency counts of Puffer [43,44]. They point to the importance of investigating the “lived-world experiences” of participants to obtain insight into how negative emotionality is perceived and utilized [46] (p. 197); they, also, could lend support to the possibilities about negative emotion and CDM espoused by Emmerling [18].

These lines of inquiry will generate a synthesis of theoretical ideas, as well as, practical suggestions for career counselors in integrating clients’ negative emotional data.

In addition, several assumptions about possible outcomes in this study emerged.

Hypothesis 1a.

Occupations that were self-reported or from computer-generated interpretative reports (i.e., Strong Interest Inventory, 16PF Questionnaire; [2,47]) were forecast to serve as triggers and elicit emotional responses and endorse the findings of Puffer [44].

- ○

- We predicated this on the findings of Staat, Gross, Guay, and Carlson, Lewis’s discussion on emotional elicitors, and the results of Puffer [44,48,49].

- ○

- We also presumed the affective reactions would be integral emotional experiences, since these most likely are related to the target, assigned vocations. Yet, the presence and influence of incidental affect on our participants are not discounted [24,26].

Hypothesis 1b.

The array (kinds) and frequency of negative emotional reactions was anticipated to be similar to and a confirmation of the outcomes reported by Puffer and Young et al. [43,44].

Hypothesis 1c.

Computer-generated occupations should elicit distinctively different negative emotionality than the self-reported careers, in particular, more anxiety in the latter and more tedium and blandness in the former. We based this expectation on the findings by Puffer [44]; hence, we expected a verification of this pattern.

Hypothesis 2.

Participants’ answers to the two investigative questions are predicted to support the predictions of adaptive influence in the CDM process (e.g., self-exploration, decision-making styles) by Emmerling, the expression of needs by Baker et al., and vocalization of personal values and life priorities addressed by Hess and Parrott [5,10,18].

- ○

- We assumed the emotions would be discreet in nature, brief in length, and “have clear cognitive content accessible to the [persons] experiencing the [affect] [25] (p. 1394).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants comprised of college students attending a Midwest university. The 256 undergraduates (79% female; 21% male) averaged 19.5 (SD = 1.56) years of age. They declared 25 academic majors. These included psychology (64%) and nursing (11%); education and undeclared (7%; each at 3.5%); business, art + design, pre-medical studies, social work, and biology (9%; each at 1.8%); sports management, music, athletic training, criminal justice, and writing (5%; each at 1%); and the remaining (4%; this comprised of eleven majors, each at 0.4%). Moreover, 91% of the respondents indicated being European American. Four percent self-identified as African American, three percent as Asian American, one percent as Hispanic American, and one percent as undesignated.

Each student learned about the purposes and risks of the study via a consent form. The document also mentioned the freedom to withdraw without penalty and requested pertinent personal information. As the undergraduates read through and signed the form, their respective professor reviewed the incentive for involvement. Rewards included participation points or extra credit.

2.2. Data Collection Process

The investigation transpired over three years. We recruited a sample from two groups of college students, first-semester sophomores (n = 160) and second-semester freshmen (n = 96). The former were enrolled in a seminar titled Life Calling and Career Planning and affirmed psychology as their major. The latter were registered in General Psychology and declared a variety of academic majors (e.g., nursing, education, business, etc.).

The sophomores were included because of the career exploration focus of the seminar. The freshmen were pursued for several reasons. First, replicating aspects of Puffer’s methodology required the inclusion of first-year undergraduates [44]. Second, we assumed freshmen responses would be similar in kind to sophomores regardless of major. They are close in age and vocational-planning experience. Both groups commonly need assistance in crystallizing their vocational preferences and career identity [50]. Collectively, the students make-up a ‘purposive sampling’ able to respond to the posed research questions [51].

2.3. Investigative Exercises

Biggerstaff underscored how qualitative designs, in general, provide researchers with opportunities to ascertain descriptions of participants’ experiences in everyday life [46]. Investigative Exercises (IE) were designed to explore the unique nuances in the negative emotional reactions of career decision-makers with vocational options. In particular, the intent was to have undergraduates record their emotional responses and reflect on the evoked affect relative to the reported occupations. The circled emotions and reflections were considered self-report data [52]. Moreover, the IEs gave the undergraduates an opportunity to increase their emotional awareness [8]. Connecting affect to reported careers helps college students be alert to feelings and symbolize affect with a word (a label), key skills in perception and understanding emotion [3,49,53].

Each IE lasted 55 min. A doctoral-level vocational researcher administered all career interest inventories and an experienced undergraduate research assistant helped in the directing of the reflective exercises. An IE comprised of three tasks: completion of a career interest inventory and two reflection handouts for processing emotional reactions to the careers. The first form (Handout 1; H1) directed undergraduates to transcribe their reported career options from the vocational measure and circle emotional reactions (positive and negative ones) to each listed occupation. The affective selections were Puffer’s State Affect Checklist (SAC) [44]. The checklist of eighteen emotional words (seven positive and eleven negative affects) was derived from the research literature of emotion science and vocational psychology. According to Rosenthal and Rosnow, “The popular word checklist has a long history in the psychological field. [It requires a] categorical judgment that is a simply ‘yes’ (circle the emotion) or ‘no’ (don’t circle it)” [52] (p. 141).

The second handout (Handout 2; H2) had three tasks. The directions on H2 requested students to transcribe the careers again, re-circle only their negative feelings from H1 (the eleven selections in the SAC), and answer two questions about the circled negative affect. To minimize order effect, the list of emotions on both forms (H1 and H2) was re-arranged for each IE [52].

Sophomores, in the seminar course, experienced three IEs in conjunction with the administration of three career interest measures. First was the My Vocational Situation (MVS) [54]. On the first side of the MVS, respondents are to list their current vocational possibilities. The undergraduates copied only three attractive vocational selections onto H1. This previously mentioned form provided three lines for each career with eighteen emotive possibilities (the SAC) under each line. Then, participants analyzed their occupations and emotional reactions with H2. This previously mentioned form contained another set of lines for each career. Yet, under each line were only the negative emotional possibilities (the eleven in the SAC) from H1 and two investigative questions. If students had negative emotional reactions to the career, they circled the affects again and then answered the questions. The probes requested—‘why’ the negative affect were circled and ‘how’ the feeling(s) helped them analyze the merit of the career option. IEs with the MVS were labeled the Top 3 and the listed careers are regarded as self-reported ones because participants self-selected the occupations as guided by the MVS directions.

The second IE was with the Strong Interest Inventory [2]. As the undergraduates examined their interpretative report, they were to select five occupations with a standard score of greater or equal to 40 (midrange to similar) starting with the highest standard score. They recorded the five selections onto H1 and circled any feelings (positive and negative) that were evoked. On H2, they listed the same careers and only the corresponding negative affect from H1 along with completing the two investigative questions. This IE was labeled Top 5 and the chosen vocations were regarded as computer-generated.

The third and final IE included the Personal Career Development Profile (PCDP) [55] that is associated with the 16PF [47]. Similar to the previous IE, students selected five vocations, recorded emotional reactions on H1, re-transcribed the occupations and only negative affect, and answered the two questions on H2. The only unique distinction was selected vocations had to have a ‘sten’ score ranging from six to ten and the list of careers had to start with the highest ‘sten’ number. This IE was also labeled Top 5 and the careers were also considered computer-reported.

Freshmen, in the General Psychology class, experienced two IEs in conjunction with the administration of the MVS and the 16PF; each one followed the same procedures as the sophomores. Unfortunately, this group in the sample had a time constraint (two-hours only) linked to the incentive for participation in the study; hence, the SII was not included. The authors determined the procedural variation would not mitigate against the purposes of the study. We assumed fewer IEs would unlikely alter the outcome. In other words, the quantity of IEs would not determine the kinds of emotional reactions by participants or the kinds of answers to the investigative questions about the selected negative affect.

2.4. Justification for Mixed Methods-Grounded Theory

Mixed Methods Research has become a popular hybrid research paradigm [56]. Researchers collect, analyze, interpret, and integrate quantitative and qualitative data [57]. In this way, closed-ended data are combined with open-ended data to allow for a richer understanding and interpretation of the phenomena being investigated, drawing on strengths inherent in qualitative and quantitative methodologies [58].

In this study, the research questions were the basis for the selection of mixed methods-grounded theory (MM-GT). Quantitative procedures were required for checking the replicative nature of the findings of Young et al. and Puffer [43,44]. Specifically, we employed frequency counts, percentage calculations, statistical analyses (e.g., Chi-Square), and positivistic principles (i.e., parsimony, comprehensiveness) in the discovery of the main kinds of negative emotions selected by the college students. These procedures enabled us to demonstrate the stability of evidence pertaining to the accessibility of emotional data for career decision-makers.

Qualitative processes were needed to ascertain undergraduates’ rationales underlying the selection of the negative affect, an unstudied phenomenon. Investigation into their “lived-world experiences” with negative emotionality [46] (p. 197) and the creation of a theoretical framework grounded in the data required the rigorous procedures in the constructivist strand of Grounded Theory (see Coding Process) [59]. The substantive codes became the basis for the development of interpretative matrices to substantiate our claim of the interpretability of emergent emotional information in the context of career decision-making.

Guetterman et al. discussed the kinds of typologies and the different approaches to integration frequently seen in mixed method designs [57]. The typology in our study was an ‘explanatory’ type. The quantitative strand preceded the qualitative procedures. We wanted to know which key negative emotions would become the foundation of the college students’ thoughts. The frequency data did not directly influence the qualitative procedures (i.e., coding) process; yet, it did play an important role in the development of a theoretical framework. Moreover, the kind of integration approach in this study was ‘building.’ The findings of the quantitative side influenced an important function in the qualitative side (i.e., development of a theoretical framework). In addition, positivistic principles (e.g., parsimony, comprehensiveness) assisted in the reporting of codes.

2.5. Coding Process

Research assistants transcribed participants’ answers to the two investigative questions on the second handout (H2) prior to the initiation of the coding process. Charmaz defined coding as placing a label on parts of data to summarize its meaning and categorize it relative to other pieces of data [59]. Essentially, a code is an interpretation of an answer identifying socio-psychological processes [51] and illumining the “lived-world experiences” of participants [46] (p. 197). In this study, the authors conducted all coding. Holton stressed the importance of researchers doing the coding because, “coding stimulates conceptual ideas” [60] (p. 3). Moreover, the coding process followed several defining components in Grounded Theory. These included selecting a sample for theory development, collecting and analyzing data simultaneously, refraining from forcing data into predetermined notions, conducting a literature review after the data analysis, and elaborating the codes, which involved clarifying their content and identify relationships between them [59].

There were four kinds of coding protocols used in this study. First was initial coding. The coder asked several questions while reading and analyzing the participants’ answers (i.e., one to two sentences). ‘What is the gist of the message?’ and ‘How can the meaning be labeled’? Coding proceeded quickly with no excessive lingering [60]. Each investigative question was coded separately. The coder kept an open mind and refrained from forcing an interpretative label onto the answer. Codes were a few words (i.e., 1–4 word labels), kept simple, close to the answers, and compared to each other [51]. Last, saturation (i.e., no new information) was monitored per administrative wave [60].

Second was focused coding. This type of code is conceptual and discriminating. The coder needs to answer the question, ‘Are there large categories that the initial codes naturally fit into?’ These decision are based on what makes the most logical and incisive sense [59].

The third and fourth codes were axial and theoretical coding. The former specifies traits or qualities belonging to a focused category [59]. In other words, a coder is searching for possible subcategories within the focused code. An axial code articulates the conditions of a focused code, answering questions such as—‘Are there relationships such as a time frame (when), geographical location (where), or person (who) within the focused code?’ Concerning the theoretical coding, the coder is trying to answer the question, “How does the substantive codes [initial, focused, and axial] relate to each other as hypotheses to be integrated into a theory” [59] (p. 63)? A theoretical code is synthetic in nature, explaining how the codes combine. Tie, Birks, and Francis noted an important contrast; initial coding fractures the story, but theoretical coding “weaves [it] back together” [51] (p. 10). Several theoretical codes can emerge telling a coherent story concerning the phenomena examined in the study.

3. Results

3.1. Negative Emotional Reactions to Reported Occupations

Table 1 displays the frequency counts for the negative emotional reactions of participants in the Investigative Exercises (IEs). Combining the eleven evoked feelings in the Top 3 and Top 5 IEs, the undergraduates self-reported 6191 negative emotional responses. Chi-squared tests indicated chance cannot account for the data [61]; for Top 3, X2 (10) = 815.27, p < 0.01, and for Top 5, X2 (10) = 1691.60, p < 0.001.

Table 1.

Frequency of Undergraduates’ Negative Emotional Reactions When Exploring Career Information in Investigative Exercises.

3.1.1. Top Six Negative Affect

As seen in Table 1, there were six reoccurring negative feelings accounting for 76% of the total affective reactions. These include blandness, anxiety, tedium, fright, tension, and fear, listed in their respective rank. Comparing the total frequency counts by freshmen and sophomores, the former endorsed the same top six negative emotions as the latter. The only variation existed in the ranking of blandness and anxiety. For sophomores, the first and second rank orders were blandness then anxiety; among freshmen, the order switched to anxiety then blandness. This outcome supports the authors’ assumption of similarity between the groups of participants regardless of major. It also verifies that the quantity of Investigative Experiences (i.e., freshmen had one less) did not determine the kinds of emotional reactions by participants.

3.1.2. Three Meta-Emotions

Using positivistic principles of parsimony and comprehensiveness [62], the six negative emotions were simplified into three meta-emotions. We sought to reduce the participants’ most frequently endorsed negative emotions to the fewest number of parameters while capturing the breadth of their emotive preferences (i.e., 76% of total reactions). Borrowing from the prototype perspective of Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, and O’Connor, we selected worry, boredom, and pressure as meta-categories [63]. Worry entailed anxiety, fright, and fear—35% of the total number of reactions. Boredom comprised of blandness and tedium encompassing 32% of the total reactions. Pressure included tension—9% of all responses. Table 2 exhibits the three meta-emotions, descriptions for each feeling, and transcripts of participants’ answers using each affect. For instance, a participant stated, “I circled blandness because it [an occupation] would be the same hard and exhausting work every day”.

Table 2.

Descriptions of Undergraduates’ Frequent Negative Emotions and Examples of Their Usage of the Emotion (Why the Selection).

3.1.3. Kinds of Affect with Self- or Computer-Reported Careers

Using only the frequencies in the meta-emotion designations and comparing Investigative Exercises (IEs; Top 3 to Top 5), students appeared to be more worried with their self-reported occupations (Top 3). A z-score test comparing the percentages for worry, 65% in Top 3 to 35% in Top 5, indicated the percentages were statistically different, z = 17.4 and p < 0.001. With the computer-reported vocations (Top 5), the undergraduates tended to be more bored. Again, a z-score test comparing the percentages for boredom, 52% in Top 5 to 22% in Top 3, revealed the proportions to be significantly different, z = 17.3, p < 0.001. Regarding pressure, participants circled tension similarly in the two kinds of IEs. A z-score test comparing the percentages, 13% in Top 3 to 12% in Top 5, noted no statistical difference, z = 0.88 and p = 0.38.

3.2. Coding Outcomes

3.2.1. Initial Codes

After participants recorded their negative emotional reactions, they answered two investigative questions—why certain emotions were selected (Q1) and how the emotions assisted processing of a career’s merit (Q2). The 256 participants disclosed 4407 answers, 2236 for Q1 and 2171 for Q2. Thirty-eight initial codes emerged over five administrative waves; the first, second, and fourth waves involved sophomores, while the third and fifth waves entailed freshmen. Saturation (i.e., no new codes) became evident in wave four and was verified in wave five [60].

Again, following positivistic principles of parsimony and comprehensiveness [62], the fewest number of initial codes covering the most answers was preferred. Hence, eight of the 38 codes covered the largest majority. More specifically, five of the 23 codes in Q1 made up 70% of the answers in Q1 (i.e., negative anticipated experience, disqualify, not interested, lacking something, and concern with their performance—listed in their respective rank). For example, negative anticipated experience indicated the negative affect of college students predicted an uncomfortable or unattractive experience. See Table 3 for more explanations and examples of answers by participants. In Q2, three of the 15 initial codes comprised 78% of the answers (i.e., reveal, eliminate, and motivate—listed in their respective rank). For instance, the theme of reveal is understood to be something was exposed—something already known or unknown (refer to Table 4).

Table 3.

The Most Frequent Initial Codes for Why Negative Emotions Were Selected.

Table 4.

The Most Frequent Initial Codes How Negative Emotions Aided in Processing the Merit of Careers.

Chi-squared tests revealed chance cannot account for the aforementioned data [61]; for Q1, X2 (4) = 415.3, p < 0.001, and for Q2, X2 (2) = 246.9, p < 0.001. Moreover, comparing the two groups in the sample, answers by freshmen to Q1 and Q2 were predominately similar to the sophomores. For Q2, the top three initial codes were identical in kind and ranking—reveal, eliminate, and motivate (see Table 4). For Q1, there were deviations. Freshmen had the same five initial codes as sophomores yet, two extra initial codes, TC (specific tasks in the career were a concern) and C (the career was challenging or difficult) were included. Their total ranking became negatively anticipated experience, disqualify, TC, C, concern with performance, lacking something, and not interested. Possibly, the freshmen’s answers to Q1 in the third and fifth administration included more nuanced answers with specific rationales relative to the sophomores. It is noteworthy that freshmen had fewer Investigative Exercises in comparison to the sophomores. Yet, the former also had the most initial codes (i.e., 13) in an administration (i.e., the third) relative to both the sophomores (i.e., 8 codes in the first, 10 in the second, and 12 initial codes in the fourth administration) and the other freshmen cohort (i.e., 10 codes in the fifth administration). This supports the authors’ assumption that the quantity of IEs would not direct the kinds of answers to the investigative questions about the selected negative affect. Further, the authors’ assumption of relative similarity between the groups of participants regardless of major was also reinforced.

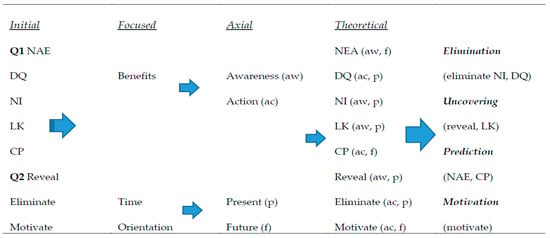

3.2.2. Focused, Axial, and Theoretical Codes

Regarding focused coding, the eight ‘primary’ initial codes naturally divided into two arching categories—benefits and time orientation [59] (See Figure 1). Benefits revolved around the notion of a profitable gain, something enhancing a person’s welfare; time orientation centered on an apparent period. Moreover, each focused code had two notable dimensions (axial codes) [59]. For benefits, there were awareness (i.e., personal mindfulness) and action (i.e., performance of a particular deed); for time orientation, there were present (i.e., in the now) and future (i.e., forthcoming) periods. Furthermore, combinations of the eight ‘primary’ initial codes varied among the axial codes (refer to Figure 1). For example, awareness fit with reveal, NAE (negative anticipated experience), NI (not interested), and LK (lacking something). For action, eliminate, DQ (disqualify), motivate, and CP (concern with performance) matched together. With a present time orientation, there were reveal, eliminate, DQ, NI, and LK while, a future timeframe included NAE, motivate, and CP. In summary, from the eight ‘primary’ initial codes, the negative emotions refreshed participants’ personal awareness and prompted them to action. These insights and desired acts related to a present or future timeframe.

Figure 1.

The Emergent Sequence of Substantive Codes in the Coding Process. Note: Participants (n = 256); Initial codes from Q1 (question 1) are NAE = negative anticipated experience; DQ = disqualify; NI = not interested; LK = what I lack; CP = concern with performance; initial codes from Q2 (question 2) are reveal = informed me of something; eliminate = remove as a possibility; and motivate = do something; focused codes are benefits (something enhancing a person’s welfare) and time orientation (an apparent period); axial codes are awareness (personal mindfulness) and action (performance of a particular task), present (in the now) and future (a forthcoming period); and theoretical codes are elimination, uncovering, prediction, and motivation.

Concerning theoretical codes, a synthesis of the eight initial, two focused, and two axial codes revealed four theoretical codes (TC) [51] (see Figure 1). The first TC was elimination. It comprised of three initial codes and three axial codes. From question 2 (Q2), there was eliminate (an action-oriented code) and from question 1 (Q1), not interested (NI; an awareness-oriented code) and disqualify (DQ; an action code). All three had a present time-orientation (an axial code). The second TC was uncovering. This included the initial code, reveal from Q2, and lacking something (LK) from Q1; both were awareness-axial codes with a present-time orientation.

The third TC was prediction. This entailed the initial codes, negative anticipated experience (NAE) and concern with performance (CP) from Q1. NAE was an awareness-oriented code, while CP was action-oriented; both had a future-time orientation. The fourth TC was motivation. It involved the initial code, motivate, that was an action-oriented code with a future time orientation.

4. Discussion

When people are emotionally agile, they recognize and harness both healthy positive and negative emotions [69]. Often, career decision-makers overlook the latter affect as they quest for pertinent information in the CDM process. The present study pursued evidence for the adaptiveness of negative emotionality in career exploration using a mixed methods approach; it looked ‘behind’ dislike reactions. Several features of Grounded Theory methodology guided the analysis of undergraduates’ “lived-world” experiences [46] (p. 197), answers to ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions about their negative feelings toward occupations. Important aspects of the findings merit detailed discussion.

4.1. Negative Emotional Reactions to Assigned Occupations

4.1.1. Hypothesis 1a—Occupations as Stimuli for Emotional Reactions

The plausibility of assigned careers triggering emotional reactions (Hypothesis 1a) was supported in this study. From Table 1, there were 6191 emotional reactions recorded in this study. With 256 participants, this is approximately 24 negative affects per undergraduate. This verifies Puffer’s finding and is comparable to his average of 31 (i.e., 14,072/451; total negative affective responses divided by sample size) [44]. Further, referring to the Total column, in Table 1, disgust and sadness were ranked low; out of eleven affective options, the former was #8 (6%) and the latter was #10 (4%). Yet, Angie et al. mentioned that disgust and sadness were “the most influential [affect] for decision-making” [25] (p. 1414). They reported effect sizes of 0.36 and 0.33, for disgust and sadness, respectively. Possibly, the conditions in the Investigative Exercises, circling elicited emotions with reported occupations, reduced the need for disgust and sadness in participants’ decision-making efforts.

As Puffer surmised, the vocational options, the target in this study, were most likely external and learned stimulus events prompting retrieval from the autobiographical memory system of participants [22,44]. Explaining affective responses to a target, Pham noted qualities in these environmental objects trigger integral emotional reactions, regardless of if the traits are “real, perceived, or only imagined” [24] (p. 156). Further, although incidental emotions are unrelated to the target and often considered ingenuous, both integral and incidental comprise the total emotional reaction to a particular target [70].

Hence, from two studies (Puffer’s and the present investigation) we have discovered the magnitude of emotional information evoked from outcomes with popular and commonly used occupational interest assessments. The enormity (i.e., 46, 398 positive and negative affect) merits intentional attention by career specialists [44]. Attending to affective responses has great potential to advance self-exploration, risk assessments, agency, and styles of decision-making. Counselors need to continue to assist clients in recognizing their feelings, identifying needs attached to the emotions, and appropriately attending to the needs in the context of career development [31,33].

4.1.2. Hypothesis 1b—Common Negative Emotional Reactions

Hypothesis 1b involved replication of Puffer’s findings with negative emotionality only (i.e., the 11 feelings) [44]. The prediction was supported. His ‘top six’ negative emotions (i.e., tedium, blandness, anxiety, tension, fright, and fear) were the same affect that emerged in the present study. Yet, the rankings were different—tedium and blandness were first and second in Puffer’s study, while blandness and anxiety were the top two in the present study [44]. More specifically, using the meta-emotion categories, boredom (i.e., tedium and blandness; 34% in 2015 to 32% in present study) and pressure (i.e., tension; 10% to 8.9%) had percentage decreases, while worry had a percentage increase (i.e., anxiety, fear, fright; 32% to 35%) in this study.

Patterns with affect in the meta-emotion, worry, appear to be consistent in Table 1. Examining the Top 3 Investigative Exercises (IE), anxiety, fear, and fright had first, second, and third rankings, respectively. In the Total column, the same affect had second, fourth, and sixth rankings, respectively. The Appraisal Tendencies Framework embodies a helpful explanation pertaining to this triad. Ferrer et al. noted its key premise, “Emotions give rise to corresponding cognitive and motivational processes” [29] (p. 6). Smith and Ellsworth identified six cognitive dimensions. These included certainty, pleasantness, control, attention, responsibility, and effort, which distinguish affect from other affect [66]. Lerner and Kiltner differentiated fear, in general, by the dimensions of low certainty (unpredictable), low pleasantness (unpleasant), and low control (situational constraint) [26].

Using Table 2, participants indicated anxiety motivated them to be cautious and focus more of their attention to the unpredictable aspects in career decision-making (CDM) [66]. They wrote, “I can carefully consider my options” and “Anxiety [helps me make] sure I reflect on the career before jumping into it”. Some undergraduates experienced fright due to the unpleasant aspects related to vocational options; these features appear to be irrelevant or unrelated to their present-time experience [66]. They wrote, “Working with criminals would make me terrified of being physically harmed” and “I would be frightened to put a patient in a worse condition”. Last, other college students circled fear with the assigned occupations due to seemingly uncontrollable factors, relative to their perceived coping abilities [26]. They explained, “I would [not] be fit for the job” and “I want to help people, but I am always afraid I will give the wrong advice”. It seems that these undergraduates perceived functioning with a lack of qualifications or coping with a disastrous future outcome as ungovernable [66].

4.1.3. Hypothesis 1c—Emotional Differences Associated with Sources of Career Recommendations

Regarding the differences between the Investigative Exercises (IEs), Hypothesis 1c was verified. As previously mentioned, participants indicated more worry with the self-reported careers (Top 3) and more boredom with their computer-generated vocations (Top 5). The pattern matches the frequency count for the negative affect in Table 1 of Puffer’s study [44].

Computer-generated interpretative reports such as the Strong Interest Inventory (SII) and the 16PF Questionnaire assign careers to respondents according to their personality traits [2,47]. However, the undergraduates in this study most likely predicated their personally assigned careers on their life experiences. These preferences may derive from a composite of information from varied sources such as past jobs or internships, respected role models, or research of occupations from Google along with their self-perceived personality features. Hence, boredom with computer-reported vocations is intuitively sensible; a computer offers vocational possibilities based on respondents’ answers to the measure’s questions not on their personal experience. Further, although the undergraduates personally identified career options in the Top 3 IEs, a lack of experience with the vocations most likely accounts for the worry-related emotions; the unpredictable, unpleasant, and uncontrollable features of the careers are understandably provoking some level of fear [26].

4.2. Hypothesis 2—Adaptive Purposes with Negative Emotions in Career Decision-Making

In the Investigative Exercises (IE), undergraduates answered two questions: ‘why’ did they select the negative feelings and ‘how’ the affect helped in the processing of the merit in a career option. An analysis of the answers resulted in eight themes (initial codes) comprising the vast majority of comments. Yet, in the synthesis of the eight initial codes along with their two focused and two axial codes [51], four theoretical codes (TC) materialized lending support to the second hypothesis in this study.

4.2.1. First Theoretical Code—Elimination

The first TC, elimination, is an obvious and natural adaptive purpose for negative emotional reactions to a vocation. When participants reflected on occupations, certain negative affect essentially meant no interest in the careers and enveloped an immediate desire to remove it from their internal choice-list. Undergraduates stated, “I should eliminate the profession as something I’m unlikely to do (eliminate);” “Not working with children (disqualify);” and “Uninteresting”, or “Not interested—lack of progress in individuals” (not interested in Table 3).

Elimination lends qualitative evidence for Emmerling’s hypotheses on agency and decision-making style in CDM [18]. Participants were deciding based on personal preferences; they eliminated options according to their discernment, not depending on others’ wisdom. An undergraduate wrote, “It helps me eliminate this option and see that while I might be good at it, I would not enjoy it” (eliminate in Table 4). In addition, elimination points to a heuristic-intuitive decision-making approach. College students were probably depending on a variety of subtle cues to direct their judgments. Emmerling mentioned this style can be adaptive and tends to be accompanied with low to moderate levels of intensity [18]. As an efficient method, respondents can reduce options freeing them to focus on alternatives with more appeal. A college student retorted, “These emotions confirm this isn’t a career that I’m working towards” (eliminate).

Using the assertions of Hess and Parrott, elimination also underscores a portion of participants’ life priorities and values [5]. For instance, the answer, “Not working with children” (disqualify in Table 3) is a priority for a specific age group with future careers. Other replies, “It is a competitive field—little gain for the kingdom” (disqualify) or “Don’t feel called into it” (not interested in Table 3)—are explicit religious values directing decisions. Moreover, elimination supports the findings of Baker et al. about need exposure [10]. The answer, “I could be doing more” (not interested), points to possible needs for significance and purpose in an undergraduate’s life.

4.2.2. Second Theoretical Code—Uncovering

In the second TC, uncovering, participants indicated the emotional reactions to a career unearthed something they did not realize about themselves (i.e., unknown) or something they already knew (e.g., a trait, value, preference) along with exposing something they lacked such as knowledge, experience, or skills. Undergraduates wrote, “Makes me realize I want something exciting”, and “Makes me aware that I am nervous” (reveal in Table 4), along with “I know little about relationships”, and “I’m not patient” (lacking something in Table 3).

Uncovering buttresses Emmerling’s prediction with self-exploration in CDM, another indication for how negative emotionality can advance career decision-making [18]. He anticipated that low to moderate levels of negative affect (NA) would not be problematic. From the aforementioned comments by the participants, it appears the NA prompted less defensiveness and an appropriate level of sensitivity to their personal weaknesses. These, in turn, lead to fair and accurate self-judgments. Although we did not ascertain participants’ ‘intensity levels’ with the negative emotion, the constructive comments appear to match low or moderate levels.

Again, utilizing the expectations of Hess and Parrott, the second TC draws attention to the previously mentioned college students’ values [5]. They desired excitement with their future occupation. Other college students’ responses revealed important character traits—“I think it shows me that this may not be a good career for me, because I lack confidence” (lacking something) or “Not smart enough” (lacking something). The comments indicate honest self-observations concerning the absence of desired qualities such as self-confidence or knowledge/wisdom. Further, undergraduates revealed religious life priorities. They stated, “Reminds me of my purpose—make a difference in [people’s] lives and reflect Christ (reveal).

4.2.3. Third Theoretical Code—Prediction

For the third TC, prediction, the undergraduates predicted a negative experience with occupations in the future or they anticipated a poor performance in the future with the vocation. Their answers communicated these concerns, “I will be sad learning about kids’ deep issues”, “Possible burnout” (negatively anticipated experience in Table 3), “I might be unsuccessful”, and “I may not do well” (concern with performance in Table 3). Further, it is unclear as to how the participants know these outcomes will occur. Possibly, they heard about these negative outcomes from past discussions or interviews with experienced workers and projected them onto themselves.

Prediction lends credence to Emmerling’s hypothesis on risk assessment in CDM [18]. The undergraduates’ answers appear to be careful calculations. They are anticipating possible unpleasant features (i.e., undesirables) in a particular occupation or forecasting a poor performance in the career if they were to pursue it. In some replies, the participants noted not having control with the career tasks or the vocational environment being uncontrollable [26]; stress, burnout, and frustration seemed imminent. They stated, “Stressful environment”, “Potential stress and draining effect”, “Possible burnout”, and “Sounds frustrating” (negatively anticipated experience). Moreover, their answers exposed thoughts suggesting they would be responsible, at some level, for the predicted negative situations [66]. They would be responsible for failure, being unsuccessful, or harming others in some fashion. They wrote, “What if I fail”, “I might be unsuccessful”, “I may not do well”, “Afraid I would lead kids astray”, and “Don’t think I can separate work and personal” (concern with performance). In addition, implied in the aforementioned answers are the undergraduates’ career values of success, satisfaction, and competence. As Hess and Parrott along with Smith and Ellsworth indicated, the underlying appraisal tendencies from their negative emotions uncover important embraced standards and principles [5,66].

4.2.4. Fourth Theoretical Code—Motivation

Regarding the last TC, motivation, the college students indicated a need to do some kind of action; this meant they would have to exert some level of effort to accomplish the desired or suggested task [66]. Some of the actions included learning, exploring, conversing, volunteering, praying, practicing, and shadowing. Specifically, they stated, “Learn study skills”, “Gets me to have a conversation with one who has this career”, “Pray about the vocation”, “Possibly volunteer at a hospital”, and “Practice harder to be more prepared” (motivate in Table 4).

Motivation supports Emmerling’s hypothesis on negative affect (NA) alerting career decision-makers to problems or gaps with the status quo [18]. Very likely, the emotions primed a deliberative process leading to goals they deemed as important to pursue. It appears participants identified holes in their knowledge base (e.g., career information, successful study habits) and experience repertoire (e.g., volunteer, job shadow). In addition, the answers also identified some of the undergraduates’ religious priorities (e.g., prayer, dependence on the divine) supporting Hess and Parrott’s assertions [5]. The college students wrote, “Pray about the vocations”, and “To rely on God” (motivate in Table 4).

4.3. A Theoretical Framework Regarding Negative Affect in CDM

“Interpretative theorizing” is stressed in Charmaz’s discussion on theory development [59] (p. 126). In this way, the development of a theoretical framework in Grounded Theory becomes a forum where researchers openly discuss their imaginative understanding of obtained data and explicate emergent concepts relative to extant literature on the topic. Our intention in this section is to envisage a theoretical framework comprised of two conceptual categories while providing an explanation of linkages between our theorizing and others’ contributions on the role for negative affect in career decision-making (CDM).

The present study pursued imaginable adaptive purposes of negative emotionality in CDM. As a result of that pursuit, two pertinent concepts in emotion-career research were unearthed: intentional accessibility and meticulous interpretation. We assert affective information can be intentionally accessed and the emotional content can be meticulously interpreted for career decision-making purposes. The following elucidates our ‘interpretative formulations’.

4.3.1. Intentional Accessibility of Clients’ Emotional Information

Almost three decades ago, Loman prompted career counselors to function as “good psychotherapists” by understanding and responding to the emotional aspects in career matters [30] (p. 8). It was a bold and insightful recommendation requiring vocational specialists to prioritize a client’s affective information. Young et al. illustrated how affect emerges in career-related conversations; their observations recorded specific feelings operating in decision-making scenarios [43]. Puffer extended the results of Young et al. by tabulating emotional data from career decision-makers [43,44]. He borrowed from Staats, Gross, Guay, and Carlson who had demonstrated how questions on a career interest instrument trigger affective responses [48]. Using the names of occupations as a stimulus event instead of the items of a vocational measure, Puffer recorded specific kinds of evoked emotions and their frequency [44]. Emergent then in the research was empirical data to support the intuitive, but reasoned assertions Loman offered to guide vocational specialists.

Within vocational psychology, some genuine efforts are evident to make the “meanings and contributions of emotion to the human experience” more central than distal [33] (p. 3). For instance, Hartung discussed a role for emotion in the Career Construction theory of Savickas [71,72]. Clearly, acknowledgement of the presence of affect has been affirmed in career developmental theory. Yet, concern remained about the accessibility of affective content. Career decision-makers needed to be able to obtain their emotional data (e.g., detect and name the affect) [53,73].

In the present study, we were able to confirm intentional accessibility and demonstrate one of many creative means to accessing affective information. This is the third study publishing a record of the accessible emotions of career decision-makers; it is the second investigation that demonstrates undergraduates processing their emotion in the context of their career choices. Moreover, two studies (i.e., Puffer’s and the present investigation) provided descriptive evidence that the source of assigned occupations associates with different kinds of evoked emotions [44]. In particular, worry (i.e., anxiety, fright, and fear) correlated more with personally assigned vocations while, boredom (i.e., blandness and tedium) related to computer-generated occupations.

Hence, vocational psychology benefits by moving beyond awareness of emotion towards accessing affect. There is an important distinction between career decision-makers being cognizant of feelings toward certain careers and actually knowing the specific evoked emotions’ place in their judgments or decisions. Greenburg and Johnson maintained optimal functioning transpires when people weave together all known sources of information [34]. Weaving cannot proceed without intentional access to emotional data.

4.3.2. Meticulous Interpretability of Emergent Emotional Information

The second interpretative concept involves the meticulous interpretability of decision-makers’ affective data. In other words, people can carefully pursue the meanings attached to their evoked emotions because they are explicable [25]. It is a logical ‘next step’ after accessing specific emotional information.

In the research literature, few studies in vocational psychology have investigated interpretability. Emmerling mentioned cognitive appraisals with some of the affect discussed in his creative theoretical framework [18]. However, interpretative grids for career decision-makers are absent. If intentional accessibility is an overlooked phenomenon, meticulous interpretability is a missing concept.

According to Angie et al., discrete emotions, the kind emerging in the CDM process, have specific thinking patterns understandable to the individuals experiencing the affective reactions [25]. A popular framework providing an interpretative structure for evoked affect is the Appraisal Tendency Framework (ATF) [26]. The six dimensions in the ATF are distinctively different categories of cognitive appraisals (e.g., pleasantness, control, certainty, effort) with two versions, a high or low form [66]. For example, key emotions in the present study were fear and boredom. Fear is defined by low pleasantness, low control, and low certainty. This appraisal profile means fear associates with thinking patterns where an individual perceives negative events as unpleasant, brought on by unpredictable forces that are outside him or her, in the environment [26]. As for boredom, its appraisal profile includes low pleasantness, low effort, and low attentional activity. This indicates a person is in an unpleasant situation and strongly desires to ignore what is transpiring. Yet, he or she stays in the situation even though nothing grabs his or her attention (i.e., to keep mentally preoccupied) [66]. Further, the cognitive processes or appraisal themes shape and prompt action tendencies—behavioral patterns focused on problem-solving difficulties or pursuing specific goals [29].

In the present study, we uncovered a four-part interpretative matrix guiding career judgments and making career decisions. Undergraduates’ selected negative emotions signified an elimination, underscored an uncovering, indicated a prediction, or marked a motivation. Further interpretative reflection led to a simplification of the foursome into a two-part grid.

First, elimination and prediction characterize a Closed Posture toward certain careers. Elimination represents a heuristic-intuitive style of decision-making [18]. Students quickly and efficiently shut out the career as an option. They were not interested and were ready to jettison the career option. No attentional activity was apparently exerted [26]. In prediction, undergraduates still did not regard the vocation as a possibility. Yet, their decision-making style was deliberative and systematic [18]; apparently, some feature in the occupation demanded their attention. They self-assessed and anticipated poorly performing in the occupation or they looked into the future and saw an unpleasant scenario. Possibly, they saw themselves as responsible for the poor performance or the environment was responsible for creating an unpleasant working experience [66].

Second, uncovering and motivation represent an Open Posture toward certain occupations. These adaptive purposes represent college students being open to a career option. Yet, in uncovering, the negative emotions signaled something they already knew about themselves or something missing within themselves (e.g., character trait). The affect apparently directed their attention inwardly [26]. In motivation, the negative affect symbolized a high level of anticipated effort [66]. The undergraduates anticipated expending both mental and physical energy to enlarge their knowledge base (e.g., learn career information) or experience repertoire (e.g., volunteer somewhere or shadow someone in the workforce) [26].

Hence, career psychology advances by offering interpretative possibilities of evoked affect relative to vocational phenomena. If emotions precede cognition, affect becomes an efficient and insightful therapeutic compass for career decision-makers, particularly with the provision of an attached meaning-making grid to aid interpretation [31]. A nascent interpretive frame for comprehending the meaning of negative affect is articulated above. The arrival, though, of a common interpretative grid useful for the CDM process is not yet at hand; it will require several iterations, an impetus for future studies.

4.4. Practical Suggestions for Career Counselors

Emmerling contended that career decision-making is a complex and evolving process. The immense number of factors (e.g., preferences, parents’ opinions, job market) swirling in the mind of undergraduate decision-makers increase the probability that their emotions become “primary variables of interest” influencing their judgments and decisions [18] (p. 43). The findings from this study inspire several real-world applications. First, vocational counselors will need to help their clients move past the common stereotype that negative emotions are inconsequential [6]. Like all emotions, negative affectivity can reveal unmet needs that necessitate attention [9]. These feelings can aid in adaptive living. For instance, anxiety can help college students exercise caution and refrain from impulsivity. A participant explained, “By being anxious, I can carefully consider my options” and another individual shared, “Anxiety can be positive in making sure I reflect on the career before jumping into it impulsively” (refer to Table 2).

Second, career specialists can include in a counseling session exploration of emotional reactions of clients. One possible method is attending to the expressed emotional words mentioned by clients. Counselors would direct their observational efforts to the emotional content in clients’ comments and then, intentionally direct clients toward an exploration of the meaning associated with their affective self-disclosures. Another possible method is to utilize Puffer’s State Affect Checklist (SAC) as a means to prompt affective information [44]. When a client possesses a list of preferred occupations generated by himself or herself or from a computer-generated interpretative report, a counselor could solicit emotional responses to the vocations with an emphasis on the negative ones that emerge. Following the observations, the vocational specialist can offer probes matched to a particular affect. For instance, with blandness, a therapist might inquire what makes the career disinteresting or dull and what makes it unpleasant [66]. For fright, what is the jarring aspect of the vocation? What is unpredictable about the career [26]? With tension, what in the career makes this uncomfortable ‘strain-ness’ reaction?

The aforementioned four adaptive purposes of negative emotions also provoke other applicative suggestions. The foursome offer additional content for discussions between clients and career counselors. First, elimination can be the first and last stop in a discussion. The career may be undesired and indeed, the vocation may be unworthy of further exploration. Yet, it might be beneficial to inquire as to what is uninteresting about the career. This does not have to be a long conversation, just enough to clarify the need to eliminate or disqualify. Second, if the need to eliminate is not present, then counselors have three other possible discussion directions—uncovering, prediction, and motivation. With uncovering, a specialist can ask what the emotive reaction reveals about them. Has it verified something clients already know about themselves? Does it expose something that is unknown to them? Is the information helpful or not? Does it reveal something they lack now and is there an interest in pursuing the missing trait, skill, etc.? Regarding prediction, the career counselor might wonder with the clients as to what they are anticipating as a future experience or future performance. Is the prediction realistic? What makes them anticipate a poor performance? Are they responsible for the failure or is the career environment responsible? Will the clients ‘not do well’ because they detest the career or possess low self-efficacy with the perceived skill-set of the career? Last, concerning motivation, a specialist can inquire what action needs to be pursued. How possible is the task? If the tasks were completed, how does the completion affect attraction to the vocation?

4.5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present study was not without limitations. First, the qualitative procedures preclude cause and effect or correlational conclusions. Second, the pursuit of self-report data assumed the undergraduates comprehended the directions in each Investigative Exercise, answered the questions in a forthright manner, and accurately transcribed their data from handout to handout [52]. Last, generalizations from the findings (i.e., coding outcomes) are limited to populations with similar characteristics of this study’s sample.

These limits notwithstanding, the importance of understanding the adaptive nature of negative emotions in the CDM process requires further consideration. For instance, other queries for analysis can be inserted into the group of questions in the Investigative Exercises (IE); pertinent ones would be—‘Did you like or dislike this career?’, ‘How comfortable are you with these negative affect?’ and ‘What level of intensity are the particular emotional reactions—low, moderate, or high’? Further, participants’ level of occupational knowledge could be obtained prior to their participation in the IEs and subsequently associated with their ratings of like/dislike of the reported vocations. Relative to this study’s sample, the experience of nonwhite racial and ethnic groups with negative affect in the CDM process needs assessment to remediate our deficiency. Last, to verify the stability of this study’s findings, a replication can be pursued.

5. Conclusions

“Negative emotions have always been with [humans]” [4] (p. 3). Yet, they remain mysterious, uncomfortable, and difficult to understand. This dichotomous perspective, unfortunately, restricts the inclusion of negative affectivity within vocational psychology—particularly in the CDM process. In the present study, undergraduates revealed their negative emotional reactions to self- or computer-generated careers and disclosed rationales for the affect. Using some of the procedures from the constructivist strand of Grounded Theory methodology, the data exposed four adaptive purposes—elimination, uncovering, prediction, and motivation. A theoretical framework for negative emotionality within the CDM process and suggestions on how to apply this information in career-counseling appointments were also proffered. Together, these contributions add to the pursuit of “a holistic portrait of human functioning—[emotion, cognition, and behavior]—within a career development paradigm” [35] (p. 146).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.P.; methodology, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; software, N.A.; validation, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; formal analysis, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; investigation, K.A.P.; resources, K.A.P.; data curation, K.A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; writing—review and editing, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; visualization, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; supervision, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; and project administration, K.A.P. and K.G.P.; funding acquisition, N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This study also resulted from the untiring and valuable assistance from Nicole Arnold, Dorothy Easterly, B.J. Fratzke, Jessica Gormong, Alex Mertz, Hosanna Ramsdell, Ana Santillan, and Tim Steenbergh.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Parson, F. Choosing a Vocation; Hard Press Publishing: Miami, FL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- SII. Strong Interest Inventory Manual; CPP: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Emotion Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life, 2nd ed.; Henry Holt: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas, J.R. Can sadness be good for you? On the cognitive, motivational, and interpersonal benefits of negative affect. In The Positive Side of Negative Emotions; Parrott, W.G., Ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, U.; Parrott, W.G. Why we need negative emotions to be happy: Against the vilification of negative emotions. Emot. Res. Newsl. Int. Soc. Res. Emot. 2010, 25, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein, H. Emotion in organizations: A review and theoretical integration. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2007, 1, 315–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, S.M.; Huang, J.Y.; Clark, M.S.; Helgeson, V.S. The positives of negative emotions: Willingness to express negative emotions promotes relationships. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, L.S. The clinical application of emotion in psychotherapy. In Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 88–101. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, L.S. Emotion-focused therapy. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 2004, 11, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.R.; McNutly, J.K.; Overall, N.C. When negative emotions benefit close relationships. In The Positive Side of Negative Emotions; Parrott, W.G., Ed.; The Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- Nesse, R.M.; Ellsworth, P.C. Evolution, emotions, and emotional disorders. Am. Psychol. 2009, 64, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceschi, A.; Hysenbelli, D.; Sartori, R.; Tacconi, G. Cooperate or defect? How an agent based model simulation on helping behavior can be an educational tool. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2014, 292, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Scalco, A.; Ceschi, A.; Sartori, R.; Rubaltelli, E. Exploring selfish versus altruistic behaviors in the ultimatum game with an agent-based model. Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2015, 372, 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Ceschi, A.; Dorofeeva, K.; Sartori, R. Studying teamwork and team climate by using a business simulation: How communication and innovation can improve group learning and decision-making performance. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2014, 38, 211–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschi, A.; Scalco, A.; Dickert, S.; Sartori, R. Compassion and prosocial behavior. Is it possible to simulate them virtually? Adv. Intell. Syst. Comput. 2015, 372, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Connelly, S. Negative emotions in informal feedback: The benefits of disappointment and drawbacks of anger. Hum. Relat. 2014, 67, 1265–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coifman, K.G.; Flynn, J.J.; Pinto, L.A. When context matters: Negative emotions predict psychological health and adjustment. Motiv. Emot. 2016, 40, 602–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmerling, R.J. Cognitive and Affective Processes in Career Decision-Making: An Integrative Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2003. UMI No. 3106375. [Google Scholar]