Support for Economic Inequality and Tax Evasion

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Tax Avoidance Research

1.2. Social Dominance and Support for Inequality

1.3. Implications of Machiavellianism

2. Research Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Survey Instrument

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

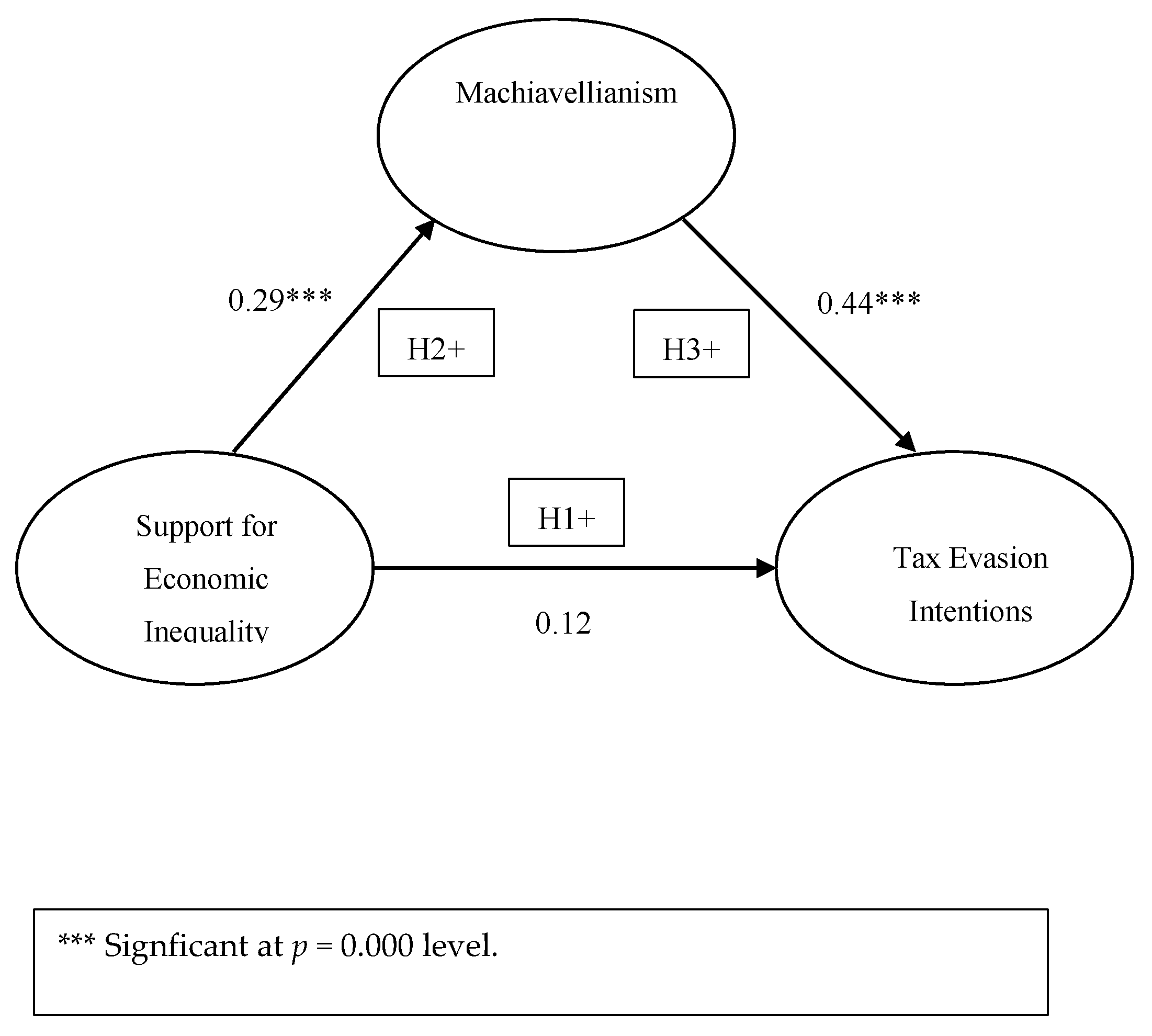

3.3. Mediation Analysis

4. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Economic equality is a bad idea dreamed up by muddle-headed “do-gooders.” It would be a big mistake to pursue it. | 0.814 | |

| Although it may be ultimately impossible, economic equality is a very worthy goal that we should definitely strive for.* | 0.808 | |

| People have no right to economic equality. All of us should get as much as we can, and if some don’t get enough, that’s their problem. | 0.838 | |

| If the natural forces of supply and demand and power make a few people immensely wealthy and millions of others poor, so be it. | 0.825 | |

| Everyone should have an equal opportunity for economic success. Those born into poor circumstances should be given extra help to make the “playing field” level for them.* | 0.855 | |

| “Access programs” to higher education, which give people from poor backgrounds extra financial support and counseling while in university, are a good idea.* | 0.842 | |

| Nobody should get extra help improving his place in society. Everyone should start off with what his family gives him, and go from there. | 0.754 | |

| Tax money should be used to make sure everyone has an adequate standard of living.* | 0.807 |

| Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| Never tell anyone the real reason you did something unless it us useful to do so. | 0.628 |

| The best way to handle people is to tell them what they want to hear. | 0.717 |

| It is safest to assume that all people have a vicious streak and it will come out when they are given a chance. | 0.549 |

| Generally speaking people won’t work hard unless they are forced to do so. | 0.528 |

| The biggest difference between most criminals and other people is that the criminals are stupid enough to get caught. | 0.503 |

| It is wise to flatter important people. | 0.638 |

| It is hard to get ahead without cutting corners here and there. | 0.504 |

| Most people forget more easily the death of a parent than the loss of their property. | 0.504 |

References

- Andreoni, J.; Erard, B.; Feinstein, J. Tax compliance. J. Econ. Lit. 1998, 36, 818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Bapuji, H.; Husted, B.W.; Lu, J.; Mir, R. Value creation, appropriation, and distribution: How firms contribute to societal economic inequality. Bus. Soc. 2018, 57, 983–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Sikka, P. Smoke and mirrors: Corporate social responsibility and tax avoidance. Account. Forum 2010, 34, 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sikka, P. The hand of accounting and accountancy firms in deepening income and wealth inequalities and the economic crisis: Some evidence. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 30, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. The impact of outcome orientation and justice concerns on tax compliance: The role of taxpayers’ identity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 629–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, R.; Putterman, L.; Van der Weele, J. Preferences for redistribution and perception of fairness: An experimental study. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2014, 12, 1059–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.-S.; Khagram, S. A comparative study of inequality and corruption. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 136–157. [Google Scholar]

- Alstadsæyer, A.; Johannesen, N.; Zucman, G. Tax evasion and inequality. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 2073–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, F.; Jost, J.T.; Rothmund, T.; Sterling, J. Neoliberal ideology and the justification of inequality in capitalist societies: Why social and economic dimensions of ideology are intertwined. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 49–88. [Google Scholar]

- Suddaby, R.; Bruton, G.D.; Walsh James, P. What we talk about when we talk about inequality: An introduction to the Journal of Management Studies special issue. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger; Bloomsbury Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, L. The Underserving Rich: American Beliefs about Inequality, Opportunity and Redistribution; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Page, B.I.; Jacobs, L.R. Class War? What Americans Really Think about Economic Inequality; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, A.S.; Enderle, G.; Jiang, K. Income inequality in the United States: Reflections on the role of corporations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Holmes, R.M. Let’s not focus on income inequality. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2019, 44, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F.A. The Road to Serfdom; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M.R. Capitalism and Freedom; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T.; Thompson, E.P. Group-based dominance and opposition to equality as independent predictors of self-esteem, ethnocentrism, and social policy attitudes among African Americans and European Americans. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 36, 209–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, F.; Sidanius, J.; Stallworth, L.M.; Malle, B.F. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F.; Bobo, L. Social dominance orientation and the political psychology of gender: A case of invariance? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 67, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, B. Highly dominating, highly authoritarian personalities. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 144, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.; Geis, F.L. Studies in Machiavellianism; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- McHoskey, J.W.; Worzel, W.; Szyarto, C. Machiavellianism and psychopathy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 192–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizi, A.; Giacomantonio, M.; Schumpe, B.M.; Manetti, L. Intention to pay taxes or avoid them: The impact of social value orientation. J. Econ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, W.E.; Wang, Z. Machiavellianism, social norms and taxpayer compliance. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2018, 27, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y.M.; Ghanem, A.J.; Rawwas, M.Y. When idealists evade taxes: The influence of personal moral philosophy on attitudes to tax evasion—A Lebanese study. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2014, 23, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allingham, M.G.; Sandmo, A. Income tax evasion: A theoretical analysis. J. Public Econ. 1972, 1, 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, J. A perspective on the experimental analysis of taxpayer reporting. Account. Rev. 1991, 66, 577–593. [Google Scholar]

- Cullis, J.; Jones, P.; Savoia, A. Social norms and tax compliance: Framing the decision to pay tax. J. Socio Econ. 2012, 41, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Pickhardt, M.; Prinz, A. Behavioral dynamics of tax evasion—A survey. J. Econ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, B.; Schneider, F. What shapes attitudes toward paying taxes? Evidence from multicultural European countries. Soc. Sci. Q. 2007, 88, 443–470. [Google Scholar]

- Blanthorne, C.; Kaplan, S. An egocentric model of the relations among the opportunity to underreport, social norms, ethical beliefs, and underreporting behaviour. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobek, D.D.; Hageman, A.M.; Kelliher, C.F. Analyzing the role of social norms in tax compliance behaviour. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 451–468. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.S.; Hecht, G.; Perkins, J.D. Social behaviors, enforcement, and tax compliance dynamics. Account. Rev. 2003, 78, 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, M. An analysis of norm processes in tax compliance. J. Econ. Psychol. 2004, 25, 213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, M. Motivation or rationalisation? Causal relations between ethics, norms and tax compliance. J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä, K.M.; Akrami, N. Social dominance orientation and climate change denial: The role of dominance and system justification. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 86, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milfont, T.L.; Sibley, C.G. The hierarchy enforcement hypothesis of environmental exploitation: A social dominance perspective. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 55, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Pratto, F. Social dominance theory: A new synthesis. In Political Psychology: Key Readings; Jost, J.T., Sidanius, J., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, M.S.; Sibley, C.G. Social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism: Additive and interactive effects on political conservatism. Polit. Psychol. 2013, 34, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstadter, R. Social Darwinism in American Thought; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T.; Glaser, J.; Kruglanski, A.W.; Sulloway, F.J. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 339–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nir, L. Motivated reasoning and public opinion perception. Public Opin. Q. 2011, 75, 504–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christie, R.; Lehmann, S. The structure of Machiavellian orientations. In Studies in Machiavellianism; Christie, R., Geis, F.L., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 359–387. [Google Scholar]

- Geis, F.; Christie, R. Overview of experimental research. In Studies in Machiavellianism; Christie, R., Geis, F.L., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 285–313. [Google Scholar]

- Dahling, J.J.; Whitaker, B.G.; Levy, P.E. The development and validation of a new Machiavellian scale. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 219–257. [Google Scholar]

- Eissa, B.; Wyland, R.; Lester, S.W.; Gupta, R. Winning at all costs: An exploration of bottom-line mentality, Machiavellianism and organizational citizenship behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2019, 29, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrova, O.; Ehlebracht, D. Cynical beliefs about human nature and income: Longitudinal and cross-cultural analyses. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 110, 116–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakalaki, M.; Richardson, C.; Thȇpaut, Y. Machiavellianism and economic opportunism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouse, M.; Giacalone, R.A.; Olsen, T.D.; Patelli, L. Individual ethical orientations and the perceived acceptability of questionable finance decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; Richards, S.C.; Paulhus, D.L. The Dark Triad of personality: A 10 year review. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2013, 7, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, P.A.; Villani, V.C.; Vickers, L.C.; Harris, J.A. A behavioral genetic investigation of the Dark Triad and the Big 5. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 44, 445–452. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. From schoolyard to workplace: The impact of bullying on sales and business employees’ Machiavellianism, job satisfaction, and perceived importance of an ethical issue. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Palomino, P.; Bañón-Gomis, A.; Linuesa-Langreo, J. Impact of peers’ unethical behavior on employees’ ethical intention: Moderated mediation by Machiavellianism orientation. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2019, 28, 185–205. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, K. Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Monbiot, G. How Did We Get into This Mess? Politics, Equality, Nature; Verso: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Capital and Ideology; Belknap Press of Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J. People, Power and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for An Age of Discontent; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khatib, J.A.; Al-Habib, M.I.; Bogari, N.; Salamah, N. The ethical profile of global marketing negotiators. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2016, 25, 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, D.; Radtke, R.R. The joint effects of Machiavellianism and ethical environment on whistle-blowing. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, W.H.; Sims, H.P., Jr. Some determinants of unethical decision behavior: An experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1978, 63, 451–457. [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty, W.H.; Sims, H.P., Jr. Organizational philosophy, policies, and objectives related to unethical decision behavior: A laboratory experiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 1979, 64, 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, J.; Kum, D. Consumer cheating on service guarantees. Acad. Market. Sci. J. 2004, 32, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, F.G.H.; Maas, V.S. Why business unit controllers create budget slack: Involvement in management, social pressure and Machiavellianism. Behav. Res. Account. 2010, 22, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.R. Attitude, Machiavellianism and the rationalization of misreporting. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 242–259. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, R.S.; Shafer, W.E.; Snell, R.S. Effects of a business ethics elective on Hong Kong undergraduates’ attitudes toward corporate ethics and social responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2013, 52, 558–591. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, W.E.; Simmons, R.S. Social responsibility, Machiavellianism and tax avoidance: A study of Hong Kong tax professionals. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2008, 21, 695–720. [Google Scholar]

- Babson College. The State of Small Business in America. 2016. Available online: http://www.babson.edu/executive-education/expanding-entrepreneurship/10k-small-business/Documents/goldman-10ksb-report-2016.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2016).

- Bobek, D.D.; Hatfield, R.C. An investigation of the theory of planned behavior and the role of moral obligation in tax compliance. Behav. Res. Account. 2003, 15, 13–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Newberry, K.; Reckers, P.M.J. The effects of moral reasoning and educational communications on tax evasion intentions. J. Am. Tax. Assoc. 1997, 19, 38–54. [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus, D.L. Measurement and control of response bias. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Variables; Robinson, L.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 1, pp. 17–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fotaki, M.; Prasad, A. Questioning neoliberal capitalism and inequality in business schools. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2015, 14, 556–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, R. From Higher Aims to Hired Hands: The Social Transformation of American Business Schools and the Unfulfulled Promise of Management as a Profession; Princeton Universiy Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marens, R. Speaking platitudes to power: Observing American business ethics in an age of declining hegemony. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey, K.; Tiratsoo, N. The Business School and the Bottom Line; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Wowak, A. The elephant (or donkey) in the boardroom: How board political ideology affects CEO pay. Adm. Sci. Q. 2017, 62, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.K.; Hambrick, D.C.; Treviño, L.K. Political ideologies of CEOs: The influence of executives’ values on corporate social responsibility. Adm. Sci. Q. 2013, 58, 197–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Frequency | Percent |

| <25 | 12 | 4.5 |

| 25–44 | 114 | 42.4 |

| 45–64 | 88 | 32.7 |

| >65 | 55 | 20.4 |

| Total | 269 | 100.0 |

| Gender | Frequency | Percent |

| Male | 79 | 29.4 |

| Female | 190 | 70.6 |

| Total | 269 | 100.0 |

| Filing Experience in Years | Frequency | Percent |

| <5 | 33 | 12.3 |

| 6–10 | 33 | 12.3 |

| 11–15 | 36 | 13.4 |

| 16–20 | 18 | 6.7 |

| 21–25 | 22 | 8.2 |

| 26–30 | 24 | 8.9 |

| >30 | 103 | 38.3 |

| Total | 269 | 100.0 |

| Prepare Own Return | Frequency | Percent |

| No | 107 | 39.8 |

| Yes | 162 | 60.2 |

| Total | 269 | 100.0 |

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Likelihood of fraud | 2.5 (1.8) | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Machiavellianism | 3.4 (1.1) | 0.428 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Impression management | 7.4 (4.8) | −0.350 ** | −0.326 ** | 1 | |||||

| 4. Support for inequality | 3.1 (1.4) | 0.221 ** | 0.403 ** | −0.070 | 1 | ||||

| 5. Opposition to inequality | 3.0 (1.4) | −0.009 | −0.063 | −0.093 | 0.505 ** | 1 | |||

| 6. Age | −0.261 ** | −0.289 ** | 0.164 ** | −0.003 | 0.132 * | 1 | |||

| 7. Gender | −0.085 | −0.137 * | 0.106 | −0.041 | 0.043 | −0.023 | 1 | ||

| 8. Years of filing experience | −0.291 ** | −0.304 ** | 0.196 ** | −0.041 | 0.133 * | 0.759 ** | −0.013 | 1 | |

| 9. Prepare own return | 0.025 | 0.105 | −0.107 | 0.101 | 0.108 | −0.144 * | −0.090 | −0.111 |

| Consequent | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machiavellianism | Tax Evasion | |||||

| Antecedent | Beta | SE | P | Beta | SE | P |

| Constant | 3.95 | 0.25 | 0.000 | 2.11 | 0.58 | 0.000 |

| Machiavellianism | ----- | ----- | ----- | 0.44 | 0.10 | 0.000 |

| Support for inequality | 0.29 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.268 |

| Impression management | −0.06 | 0.01 | 0.000 | −0.08 | 0.02 | 0.000 |

| Age | −0.32 | 0.06 | 0.000 | −0.31 | 0.12 | 0.009 |

| Gender | −0.24 | 0.12 | 0.048 | −0.09 | 0.21 | 0.664 |

| Model F (p-value) | 31.0(0.000) | 18.2(0.000) | ||||

| Adjusted R Square | 0.32 | 0.26 | ||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shafer, W.E.; Wang, Z.; Hsieh, T.-S. Support for Economic Inequality and Tax Evasion. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198025

Shafer WE, Wang Z, Hsieh T-S. Support for Economic Inequality and Tax Evasion. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198025

Chicago/Turabian StyleShafer, William E., Zhihong Wang, and Tien-Shih Hsieh. 2020. "Support for Economic Inequality and Tax Evasion" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198025

APA StyleShafer, W. E., Wang, Z., & Hsieh, T.-S. (2020). Support for Economic Inequality and Tax Evasion. Sustainability, 12(19), 8025. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198025