Originalities of Willow of Salix atrocinerea Brot. in Mediterranean Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Data Collection

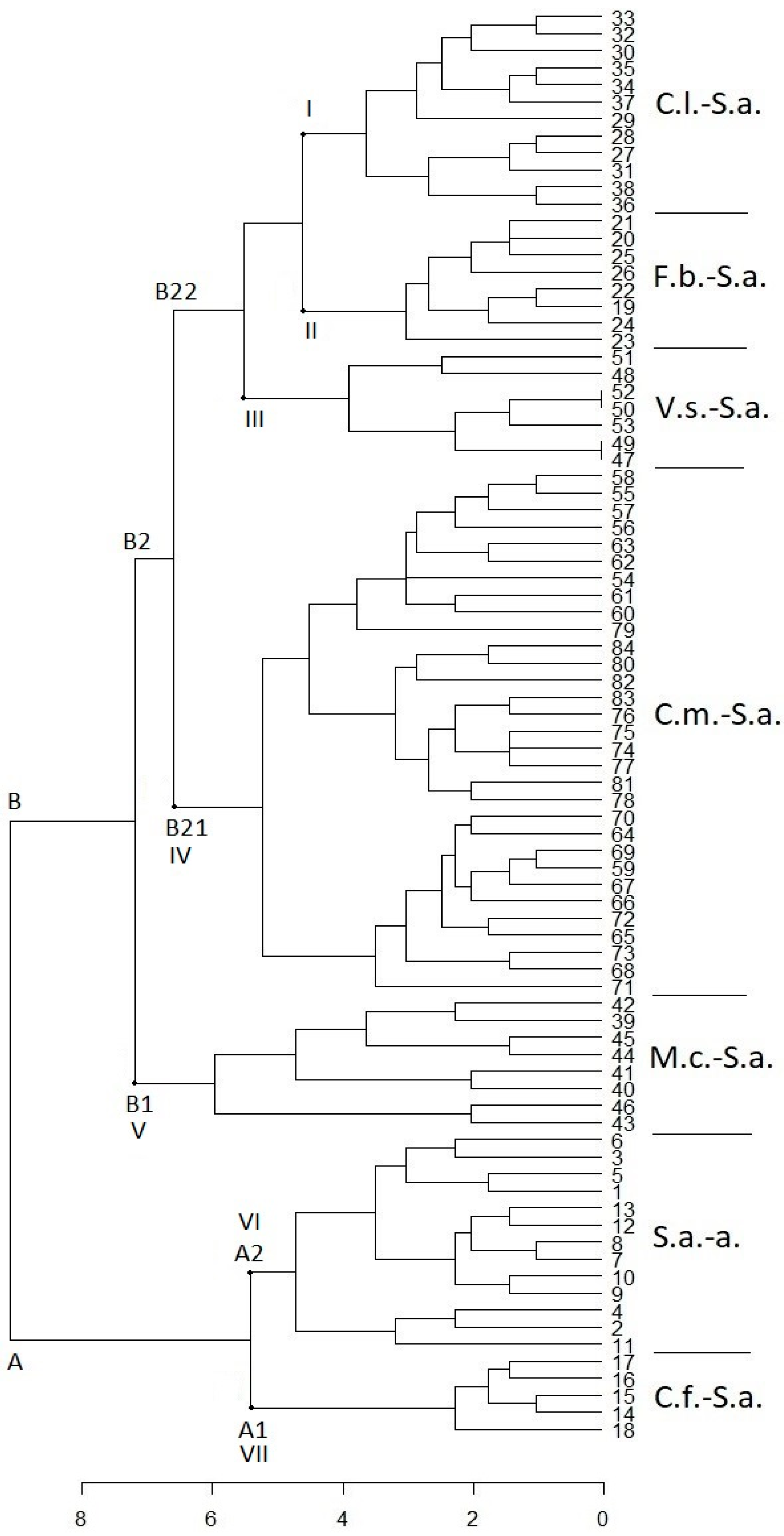

3. Results and Discussion

Description of Willow Communities

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Syntaxonomical Scheme

References

- Camporeale, C.; Perucca, E.; Ridolfi, L.; Gurnell, A.M. Modeling the Interactions between River Morphodynamics and Riparian Vegetation. Rev. Geophys. 2013, 51, 379–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.; Lousã, M.; Oliveira Paes, A.P. As comunidades ribeirinhas da bacia hidrográfica do rio Sado (Alentejo, Portugal). Actas Colóquio Int. Ecol. 1996, 1, 291–320. [Google Scholar]

- Raposo, M.; Castro, M.C.; Pinto-Gomes, C. The application of symphytosociology in landscape architecture in the Western Mediterranean. Botanique 2016, 1, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Portela-Pereira, E. Análise Geobotânica dos Bosques e Galerias Ripícolas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Tejo em Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Mapa de series, geosséries y geopermaseries de vegetación de España. (Memoria del mapa de vegetatión potencial de España). Parte II. Itinera Geobot. 2011, 18. Available online: https://floramontiberica.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/itinerageobotanica_181_2011.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Costa, J.C.; Neto, C.; Aguiar, C.; Capelo, J.; Espírito Santo, M.D.; Honrado, J.J.; Gomes, C.P.; Monteiro-Henriques, T.; Sequeira, M.; Lousã, M. Vascular plant communities in Portugal (continental, the Azores and Madeira). Glob. Geobot. 2012, 2, 1–180. [Google Scholar]

- Mucina, L.; Bültmann, H.; Dierßen, K.; Theurillat, J.-P.; Raus, T.; Čarni, A.; Šumberová, K.; Willner, W.; Dengler, J.; García, R.G.; et al. Vegetation of Europe: Hierarchical floristic classification system of vascular plant, bryophyte, lichen, and algal communities. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2016, 19, 3–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, C. A Flora e a Vegetação do superdistrito Sadense (Portugal). Guineana 2002, 8, 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Valdés, E.; Costa, M.; Castroviejo, S. Vegetación de Doñana (Huelva, España). Lazaroa 1980, 2, 5–190. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, G.; Bagella, S.; Biondi, E.; Farris, E.; Filigheddu, R.; Mossa, L. Vegetazione forestale e serie di vegetazione della Sardegna (con rappresentazione cartografica. Fitosociologia 2009, 46, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Angius, R.; Bacchetta, G. Boschi e boscaglie ripariali del Sulcis-Iglesiente (Sardegna Sud-Occidentale, Italia). UNICA IRIS 2009, 45, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Biondi, E.; Bagella, S. Vegetazione e paesaggio vegetale dell àrcipelago di La Maddalena (Sardegna nord-orientale). Fitosociologia 2005, 42, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Braun-Blanquet, J.; Pavillard, J. Vocabulaire de Sociologie Végétale, 3rd ed.; Roumégous et Déhan: Montpellier, France, 1928. [Google Scholar]

- Tüxen, R. Die Pflanzengesellschaften Nordwestdeutschlands; Mitt. Flor.-Soz. Arbeitsgem: Hannover, Germany, 1937; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Géhu, J.M.; Rivas-Martínez, S. Notions fondamentales de phytosociologie. In Syntaxonomie. Vaduz: Berichte Internationalen Symposien der Internationalen Vereinigung fur Vegetationskunde; J. Cramer.: Vaduz, Liechtenstein, 1981; pp. 5–33. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martinez, S. Notions on dynamic-catenal phytosociology as a basis of landscape science. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2005, 139, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazare, J.J. Phytosociologie dynamico-caténale et gestion de la biodiversité. Acta Bot. Gall. 2009, 156, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Biondi, E. Phytosociology today: Methodological and conceptual evolution. Plant Biosyst. 2011, 145, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, A.X.P. Flora de Portugal, 2nd ed.; Bertrand: Lisboa, Portugal, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A. Nova Flora de Portugal (Continente e Açores); Escolar Editora: Lisboa, Portugal, 1971; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.A. Nova Flora de Portugal (Continente e Açores); Escolar Editora: Lisboa, Portugal, 1984; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J.; Rocha Afonso, M. Nova Flora de Portugal (Continente e Açores); Escolar Editora: Lisboa, Portugal, 1984; Volume III. [Google Scholar]

- Castroviejo, S. Flora Ibérica. Plantas Vasculares da Península Ibérica e Ilhas Baleares; Real Jardín Botánico; CSIC: Madrid, Spain, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Valdés, B.; Talavera, S.; Fernández-Galiano, E. Flora Vascular de Andalucía Occidental; Ketres Editora, S.A.: Barcelona, Spain, 1987; Volume 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Portela-Pereira, E.; Capelo, J.; Neto, C.; Costa, J.C. Síntese do Conhecimento Taxonómico do Género Salix L. em Portugal Continental. Silva Lusit. 2013, 21, 103–133. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.R. Hierarchical Grouping to Optimize an Objective Function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Maarel, E. Transformation of cover-abundance values in phytosociology and its effects on community similarity. Vegetatio 1979, 39, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, E.; Valle, F. Aportaciones fitosociologicas sobre sierra morena oriental (Andalucia, España). Monogr. Flora Veg. Béticas 1990, 4, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S. Mapas de series, geoseries y geopermaseries de vegetación de España [Memoria del mapa de vegetación potencial de España]. Parte I. Itinera Geobot. 2007, 17, 5–436. Available online: https://floramontiberica.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/itinerageobotanica_17_2007.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Penas, Á.; Díaz González, T.E.; Cantó, P.; del Río, S.; Costa, J.C.; Herrero, L.; Molero, J. Biogeographic Units of the Iberian Peninsula and Baelaric Islands to District Level. A Concise Synopsis. In The Vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula: Volume 1; Loidi, J., Ed.; Plant and Vegetation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 131–188. ISBN 978-3-319-54784-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Martínez, S.; Penas, Á.; del Río, S.; Díaz González, T.E.; Rivas-Sáenz, S. Bioclimatology of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. In The Vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula: Volume 1; Loidi, J., Ed.; Plant and Vegetation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–80. ISBN 978-3-319-54784-8. [Google Scholar]

- Fenu, G.; Fois, M.; Cañadas, E.M.; Bacchetta, G. Using endemic-plant distribution, geology and geomorphology in biogeography: The case of Sardinia (Mediterranean Basin). Syst. Biodivers. 2014, 12, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun-Blanquet, J. Fitosociología. Bases Para el Estudio de las Comunidades Vegetales; H. Blume: Madrid, Spain, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetta, G. Contributo alla conoscenza dei boschi a Laurus nobilis L. della Sardegna, habitat prioritario ai sensi della Direttiva 92/43/CEE. Fitosociologia 2007, 44, 244–249. [Google Scholar]

- Espírito-Santo, D.; Capelo, J.; Neto, C.; Pinto-Gomes, C.; Ribeiro, S.; Quinto Canas, R.; Costa, J.C. Lusitania. In The Vegetation of the Iberian Peninsula. Plant and Vegetation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 35–82. [Google Scholar]

- Quinto-Canas, R. Flora y Vegetación de la Serra do Caldeirão—Aproximación Fitosociológica. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Jaén, Jaén, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Gomes, C.; Paiva-Ferreira, R. Flora e Vegetação Barrocal Algarvio, Tavira—Portimão; CCDR Algarve: Faro, Portugal, 2005; ISBN 972-95734-9-2. [Google Scholar]

- Quinto-Canas, R.; Mendes, P.; Meireles, C.; Musarella, C.; Pinto-Gomes, C. The Agrostion castellanae Rivas Goday 1957 corr. Rivas Goday & Rivas- Martínez 1963 alliance in the southwestern Iberian Peninsula. Plant Sociol. 2018, 55, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenu, G.; Bacchetta, G.; Christodoulou, C.S.; Cogoni, D.; Fournaraki, C.; Gian Pietro, G.G.; Gotsiou, P.; Kyratzis, A.; Piazza, C.; Vicens, M.; et al. A Common Approach to the Conservation of Threatened Island Vascular Plants: First Results in the Mediterranean Basin. Diversity 2020, 12, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Numerical Order | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of relevées | 12 | 8 | 7 | 31 | 8 | 13 | 5 |

| Acronym | C.l.-S.a. | F.b.-S.a. | V.s.-S.a. | C.m.-S.a. | M.c.-S.a. | S.a.-a. | C.f.-S.a. |

| Characteristics and differentials | |||||||

| Salix atrocinerea | V | V | V | V | V | IV | . |

| Carex lusitanica | V | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Thelypteris palustris | V | . | V | . | . | . | . |

| Myrica gale | V | . | . | . | . | . | . |

| Frangula alnus subsp. baetica | IV | V | . | . | . | . | . |

| Salix salviifolia subsp. australis | II | II | . | . | . | V | V |

| Cheirolophus uliginosus | . | III | . | . | . | . | . |

| Leuzea longifolia | . | II | . | . | . | . | . |

| Euphorbia uliginosa | . | II | . | . | . | . | . |

| Vitis sylvestris | . | . | V | . | . | III | . |

| Rubus ulmifolius | . | . | IV | V | V | V | . |

| Fraxinus angustifolia | . | . | II | . | . | II | III |

| Dioscorea communis | . | . | . | V | . | II | . |

| Carex microcarpa | . | . | . | V | . | . | . |

| Smilax aspera | . | . | . | V | . | . | . |

| Quercus ilex | . | . | . | V | . | . | . |

| Brachypodium sylvaticum | . | . | . | IV | . | . | II |

| Oenanthe crocata | . | . | . | III | IV | . | . |

| Hypericum hircinum subsp. hircinum | . | . | . | III | . | . | . |

| Euphorbia meuselii | . | . | . | III | . | . | . |

| Nerium oleander | . | . | . | III | . | . | . |

| Bellium bellidioides | . | . | . | III | . | . | . |

| Bryonia dioica | . | . | . | . | . | II | . |

| Securinega tinctorea | . | . | . | . | . | + | . |

| Salix neotricha | . | . | . | . | . | III | V |

| Clematis flammula | . | . | . | . | . | . | V |

| Vinca difformis | . | . | . | . | . | . | IV |

| Equisetum ramosissimum | . | . | . | . | . | . | IV |

| Aristolochia paucinervis | . | . | . | . | . | . | I |

| Equisetum telmateia | . | . | . | . | . | . | I |

| Hedera canariensis | . | . | . | . | . | II | . |

| Myrtus communis | . | . | . | . | V | . | . |

| Carex hispida | . | . | . | . | III | . | . |

| Tamarix africana | . | . | . | . | III | . | . |

| Ordinal Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface (m²) | 150 | 100 | 150 | 300 | 200 | 250 | 200 | 100 |

| Altitude (m) | 48 | 64 | 43 | 86 | 65 | 27 | 45 | 50 |

| Cover rate (%) | 85 | 80 | 80 | 95 | 85 | 80 | 85 | 90 |

| Orientation | W | W | N | S | NW | W | N | N |

| Slope (%) | 12 | 18 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| Average heigth (m) | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Number of species | 24 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 28 | 32 | 36 | 36 |

| Association characteristics | ||||||||

| Salix atrocinerea | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Frangula alnus subsp. baetica | + | 1 | . | 2 | 1 | 1 | + | 3 |

| Cheirolophus uliginosus | . | . | + | . | 1 | . | 2 | + |

| Leuzea longifolia | . | . | . | + | + | 1 | . | . |

| Salix salviifolia subsp. australis | . | . | . | . | . | + | . | + |

| Euphorbia uliginosa | . | . | . | . | . | . | + | + |

| Companions | ||||||||

| Molinia caerulea subsp. arundinacea | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Rubus ulmifolius | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | + | + |

| Quercus suber | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Erica ciliaris | 1 | . | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ulex australis subsp. welwitschianus | + | + | + | + | + | . | + | + |

| Brachypodium phoenicoides | 1 | + | . | 1 | 1 | + | + | 1 |

| Ulex minor var. lusitanicus | . | + | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Erica erigena | 1 | + | 1 | . | . | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Lonicera hispanica | . | + | 1 | . | 2 | 1 | + | + |

| Schoenus nigricans | . | . | + | + | 1 | 1 | + | 1 |

| Calluna vulgaris | + | + | . | . | + | + | + | + |

| Asparagus aphyllus | + | + | . | + | + | . | + | + |

| Schirpus holoschoenus | + | + | + | . | . | + | + | + |

| Daphne gnidium | + | . | . | + | + | + | . | + |

| Agrostis castellana | + | + | . | + | . | + | + | . |

| Pteridium aquilinum | . | . | 1 | + | . | + | + | + |

| Lepidophorum repandum | . | . | . | + | + | + | + | + |

| Prunella vulgaris | . | + | . | + | + | + | + | . |

| Holcus lanatus | + | + | + | . | . | . | + | + |

| Juncus rugosus | + | . | + | + | . | . | . | + |

| Crataegus monogyna | . | . | + | + | + | + | . | . |

| Erica scoparia | + | . | + | . | . | . | + | + |

| Panicum repens | + | + | + | . | . | . | + | . |

| Quercus lusitanica | . | + | . | . | + | . | + | + |

| Juncus effusus | 1 | + | . | . | . | + | . | . |

| Erica arborea | . | . | . | . | + | + | . | + |

| Arbutus unedo | . | . | . | . | + | + | + | . |

| Pseudarrhenatherum longifolium | . | . | . | . | + | + | . | + |

| Genista triacanthos | + | . | . | . | + | . | . | + |

| Euphorbia transtagana | . | . | + | . | . | . | + | + |

| Agrostis stolonifera | . | . | + | . | + | + | . | . |

| Halimium calycinum | . | + | . | . | + | . | . | + |

| Fuirena pubescens | . | + | + | + | . | . | . | . |

| Stachys officinalis | . | . | . | . | + | + | + | . |

| Halimium lasianthum | + | . | . | . | . | . | + | + |

| Erica lusitanica | . | . | 1 | . | . | + | . | . |

| Lavandula lusitanica | . | . | . | . | + | . | . | + |

| Danthonia decumbens | . | . | . | . | + | . | + | + |

| Narcissus bulbocodium | . | . | . | . | . | + | . | + |

| Holcus mollis | + | . | . | . | . | . | . | + |

| Hyacinthoides transtagana | . | . | . | . | . | + | . | + |

| Laurus nobilis | + | . | . | . | . | . | + | . |

| Lobela urens | . | . | . | . | . | + | + | . |

| Potentilla erecta | . | . | . | . | . | + | + | . |

| Ordinal Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface (m²) | 30 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 25 |

| Altitude (m) | 84 | 49 | 26 | 66 | 61 | 42 | 46 |

| Cover rate (%) | 95 | 95 | 85 | 80 | 85 | 90 | 95 |

| Orientation | S | N | W | NW | NE | N | N |

| Slope (%) | 6 | 12 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| Average heigth (m) | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Number of species | 25 | 26 | 33 | 21 | 26 | 27 | 31 |

| Association characteristics | |||||||

| Molinia caerulea subsp. arundinacea | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Schoenus nigricans | 1 | 2 | 2 | + | + | 1 | + |

| Schirpus holoschoenus | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Cheirolophus uliginosus | + | . | + | 1 | + | + | 2 |

| Prunella vulgaris | + | . | + | . | + | + | + |

| Erica erigena | . | + | + | + | . | + | 1 |

| Holcus lanatus | . | + | . | + | + | 1 | + |

| Euphorbia uliginosa | . | + | . | . | . | . | + |

| Leuzea longifolia | . | . | + | + | . | . | . |

| Fuirena pubescens | . | . | . | . | + | + | . |

| Companions | |||||||

| Erica ciliaris | 1 | 1 | + | 1 | + | + | + |

| Ulex minor var. lusitanicus | + | 1 | + | + | + | 1 | + |

| Brachypodium phoenicoides | + | + | 1 | + | + | + | + |

| Salix atrocinerea | + | + | + | + | + | + | . |

| Ulex australis subsp. welwitschianus | . | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Pteridium aquilinum | 1 | . | . | + | 2 | + | + |

| Calluna vulgaris | + | + | + | + | . | . | 1 |

| Daphne gnidium | + | + | + | . | . | + | + |

| Holcus mollis | + | + | + | . | + | . | + |

| Erica scoparia | . | + | + | . | + | + | + |

| Euphorbia transtagana | + | . | + | . | . | + | 1 |

| Crataegus monogyna | + | + | . | + | + | . | . |

| Agrostis castellana | + | . | . | . | + | + | + |

| Asparagus aphyllus | + | + | + | . | . | . | + |

| Lepidophorum repandum | . | + | + | . | + | . | + |

| Juncus rugosus | . | . | + | . | + | + | . |

| Ditrichia viscosa | + | . | + | . | + | . | . |

| Juncus effusus | + | . | . | . | . | + | + |

| Potentilla erecta | + | . | + | . | . | . | + |

| Frangula alnus subsp. baetica | + | + | + | . | . | . | . |

| Halimium calycinum | . | + | + | . | + | . | . |

| Stachys officinalis | . | . | + | + | . | . | + |

| Halimium lasianthum | . | . | + | . | . | + | + |

| Lobelia urens | . | . | + | + | . | . | + |

| Hyacinthoides transtagana | . | . | + | + | . | . | + |

| Cistus psilosepalus | . | + | . | . | . | + | + |

| Panicum repens | . | . | . | . | + | + | + |

| Erica lusitanica | + | . | . | . | 1 | . | . |

| Narcissus bulbocodium | + | . | + | . | . | . | . |

| Lonicera hispanica | + | + | . | . | . | . | . |

| Erica arborea | . | . | + | . | . | + | . |

| Carex riparia | . | . | . | 1 | . | + | . |

| Agrostis stolonifera | . | + | . | . | + | . | . |

| Euphorbia boetica | . | + | . | . | + | . | . |

| Ordinal Number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface (m2) | 200 | 100 | 250 | 300 | 200 |

| Altitude (m) | 160 | 30 | 130 | 185 | 155 |

| Cover rate (%) | 85 | 85 | 95 | 90 | 85 |

| Orientation | NE | N | O | O | S |

| Slope (%) | 3 | 2 | 15 | 3 | 2 |

| Average height (m) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Number of species | 18 | 16 | 14 | 31 | 29 |

| Association characteristics | |||||

| Salix salviifolia subp. australis | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Salix neotricha | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Clematis flammula | + | + | + | 1 | + |

| Vinca difformis | . | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Equisetum ramosissimum | + | 1 | . | + | 1 |

| Fraxinus angustifolia | . | . | + | 1 | + |

| Brachypodium sylvaticum | . | . | . | 1 | + |

| Aristolochia paucinervis | . | . | . | . | + |

| Equisetum telmateia | . | . | . | . | + |

| Companions | |||||

| Rubus ulmifolius | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ceratonia siliqua | + | + | 1 | + | + |

| Smilax aspera var. altissima | 1 | . | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Scirpoides holoschoenus | + | + | . | 1 | 1 |

| Nerium oleander | 1 | . | + | 1 | + |

| Arundo donax | + | 1 | 1 | . | + |

| Lythrum salicaria | + | 1 | . | + | + |

| Mentha suaveolens | + | + | . | + | + |

| Dorycnium rectum | . | + | . | + | 2 |

| Carex hispida | + | . | . | + | + |

| Rosa pouzinii | . | 1 | . | + | . |

| Calystegia sepium | . | 1 | . | . | + |

| Viburnum tinus | + | . | . | + | . |

| Aristolochia baetica | . | + | . | . | + |

| Paspalum dilatatum | . | + | . | + | . |

| Dittrichia viscosa subsp. revoluta | . | . | + | . | + |

| Samolus valerandi | . | . | . | + | + |

| Cyperus longus subsp. badius | . | . | . | + | + |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raposo, M.; Quinto-Canas, R.; Cano-Ortiz, A.; Spampinato, G.; Pinto Gomes, C. Originalities of Willow of Salix atrocinerea Brot. in Mediterranean Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198019

Raposo M, Quinto-Canas R, Cano-Ortiz A, Spampinato G, Pinto Gomes C. Originalities of Willow of Salix atrocinerea Brot. in Mediterranean Europe. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198019

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaposo, Mauro, Ricardo Quinto-Canas, Ana Cano-Ortiz, Giovanni Spampinato, and Carlos Pinto Gomes. 2020. "Originalities of Willow of Salix atrocinerea Brot. in Mediterranean Europe" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198019

APA StyleRaposo, M., Quinto-Canas, R., Cano-Ortiz, A., Spampinato, G., & Pinto Gomes, C. (2020). Originalities of Willow of Salix atrocinerea Brot. in Mediterranean Europe. Sustainability, 12(19), 8019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198019