Work–Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Sustainable Creative Performance

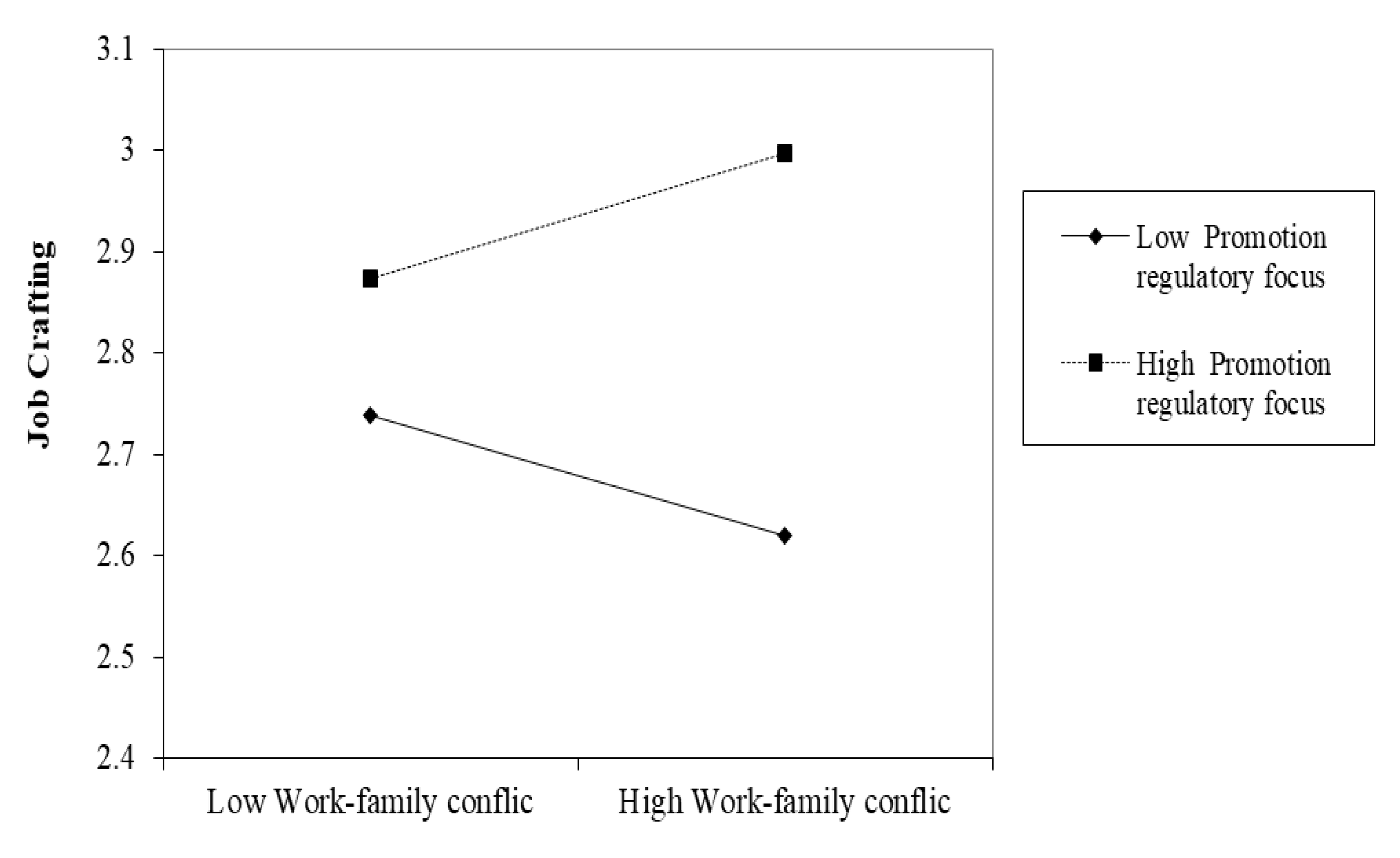

2.2. The Moderating Effect between Work–Family Conflict and Job Crafting via Promotion Regulatory Focus

2.3. Job Crafting and Sustainable Creative Performance

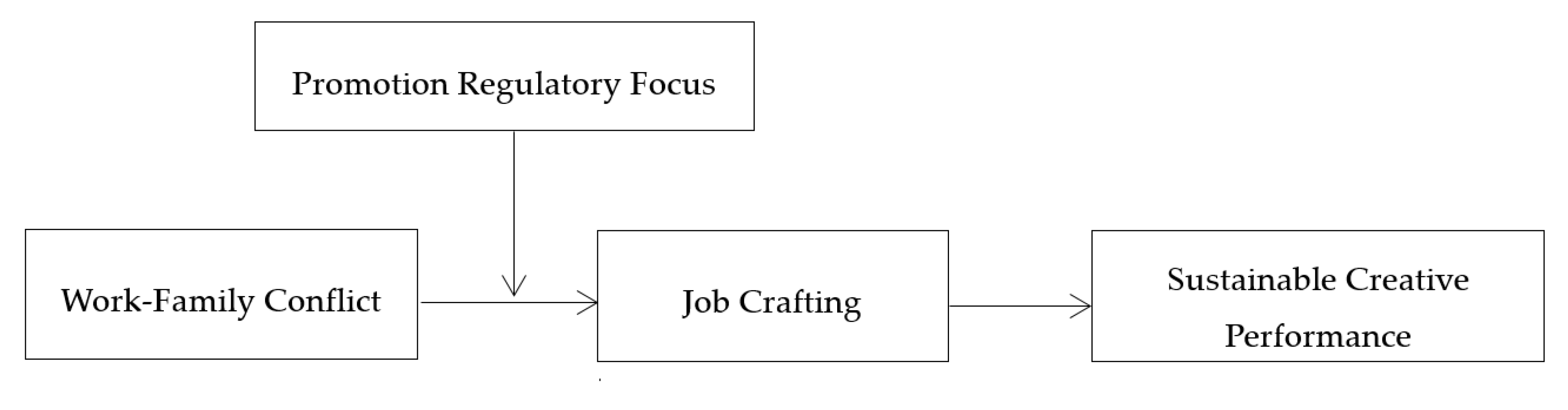

2.4. The Integrated Effect of Model

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Work-Family Conflict

3.2.2. Job Crafting

3.2.3. Promotion Regulatory Focus

3.2.4. Sustainable Creative Performance

3.2.5. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life.

- The amount of time my job takes up makes it difficult to fulfill family responsibilities.

- Things I want to do at home do not get done because of the demands my job puts on me.

- My job produces strain that makes it difficult to fulfill family duties.

- Due to work-related duties, I have to make changes to my plans for family activities.

- Introduce new approaches on your own to improve your work in the classroom.

- Change minor work procedures that you think are not productive (such as lunch time or transition routines) on your own.

- On your own, change the way you do your job to make it easier for yourself.

- Rearrange equipment or furniture in the play areas of your classroom on your own.

- Organize special events in your classroom (such as celebrating a child’s birthday, etc.) on your own.

- On your own, bring in other materials from home for the classroom (such as empty jars or egg cartons).

- I am focused on achieving positive outcomes in my life.

- I typically focus on the successes I hope to achieve in the future.

- I often think about how I will achieve my work goals.

- I am more orientated towards achieving success than preventing failure.

- Comes up with creative solutions to problems.

- Comes up with new and practical ideas to improve performance.

- Searches out new technologies, processes, techniques, and/or product ideas.

- Not afraid to take risks.

- Analyzing problems from new perspectives.

References

- Di Fabio, A. The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for Well-Being in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, T.; Von Staden, P.; Kwon, K.-S. Sustainable Economic Growth and the Adaptability of a National System of Innovation: A Socio-Cognitive Explanation for South Korea’s Mired Technology Transfer and Commercialization Process. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Prins, P.; Stuer, D.; Gielens, T. Revitalizing social dialogue in the workplace: The impact of a cooperative industrial relations climate and sustainable HR practices on reducing employee harm. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 31, 1684–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuti, A.; Giancaspro, M.L. People Make the Difference: An Explorative Study on the Relationship between Organizational Practices, Employees’ Resources, and Organizational Behavior Enhancing the Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.G.; Cabral-Cardoso, C. Work-family culture in academia: A gendered view of work-family conflict and coping strategies. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2008, 23, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.G. Narratives about Work and Family Life among Portuguese Academics. Gend. Work Organ. 2014, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, J.H.; Butts, M.M.; Casper, W.J.; Allen, T.D. In Search of Balance: A Conceptual and Empirical Integration of Multiple Meanings of Work-Family Balance. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 70, 167–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams J, C. Will working mothers take your company to court? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 90, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 25, 1069–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, P.; Liao, J.; Hao, P.; Mao, J. Abusive supervision and employee creativity. Manag. Decis. 2016, 54, 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, S.K.; Hutchinson, S.; Hawthorne, L.; Cosley, B.J.; Ell, S.W. Is pressure stressful? The impact of pressure on the stress response and category learning. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2014, 14, 769–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, R.P.; Pitassi, C. Sustainability-oriented innovations: Can mindfulness make a difference? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villajos, E.; Tordera, N.; Peiró, J.M. Human Resource Practices, Eudaimonic Well-Being, and Creative Performance: The Mediating Role of Idiosyncratic Deals for Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-H. Electronic human resource management and organizational innovation: The roles of information technology and virtual organizational structure. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J.; Higgins, E. Regulatory Focus Theory: Implications for the Study of Emotions at Work. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2001, 86, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbeto, D.L.; Hon, A.H.Y. A Dualistic Model of Tourism Seasonality: Approach–Avoidance and Regulatory Focus Theories. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2019, 43, 734–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T.; Scholer, A.A. Engaging the consumer: The science and art of the value creation process. J. Consum. Psychol. 2009, 19, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutnick, D.; Walter, F.; Nijstad, B.A.; De Dreu, C.K. Creative performance under pressure: An integrative conceptual framework. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 189–207. [Google Scholar]

- De Cooman, R.; Stynen, D.; Broeck, A.V.D.; Sels, L.; De Witte, H. How job characteristics relate to need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: Implications for work effort. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 43, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, E.; Moen, P.; Tranby, E. Changing Workplaces to Reduce Work-Family Conflict. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 76, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B. Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2010, 36, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkikangas, A.; Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Antecedents of daily team job crafting. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a Job: Revisioning Employees as Active Crafters of Their Work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Dutton, J.E.; Wrzesniewski, A. Job crafting and meaningful work. Purp. Mean. Workplace 2013, 81, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W. Job crafting in changing organizations: Antecedents and implications for exhaustion and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D.; van Rhenen, W. Job Crafting at the Team and Individual Level. Group Organ. Manag. 2013, 38, 427–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Parker, S.K. Reorienting job crafting research: A hierarchical structure of job crafting concepts and integrative review. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 40, 126–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D.C.; Lucas, G.M.; Rusbult, C.; Finkel, E.J.; Kumashiro, M. Perceived Support for Promotion-Focused and Prevention-Focused Goals. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 20, 787–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, S.; Rohmann, E.; Förster, J. Regulatory focus and regulatory mode–Keys to narcissists’ (lack of) life satisfaction? Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019, 138, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, C.A.; Meriac, J.P.; Overstreet, B.L.; Apodaca, S.; McIntyre, A.L.; Park, P.; Godbey, J.N. A meta-analysis of the regulatory focus nomological network: Work-related antecedents and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, V.; Hekkert-Koning, M. To craft or not to craft. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E. Trait-level and week-level regulatory focus as a motivation to craft a job. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetland, J.; Hetland, H.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Daily transformational leadership and employee job crafting: The role of promotion focus. Eur. Manag. J. 2018, 36, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPietro, W.R.; Anoruo, E. Creativity, innovation, and export performance. J. Policy Model. 2006, 28, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stobbeleir, K.E.M.; Ashford, S.J.; Buyens, D. Self-Regulation of Creativity at Work: The Role of Feedback-Seeking Behavior in Creative Performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2011, 54, 811–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Conti, R.; Coon, H.; Lazenby, J.; Herron, M. Assessing the work environment for creativity. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1154–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J.H.; Shriner, M. Examining Relationships between Transformational Leadership and Employee Creative Performance: The Moderator Effects of Organizational Culture. J. Creat. Behav. 2017, 53, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-H.; Parker, S.K.; De Jong, J.P.J. Need for Cognition as an Antecedent of Individual Innovation Behavior. J. Manag. 2011, 40, 1511–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, G.A.; King, L.A.; King, D.W. Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work-family conflict with job and life satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Shockley, K.M. A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work–family conflict. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 539–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockwood, P.; Jordan, C.H.; Kunda, Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Peeters, M.C.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Hetland, J. Crafting a job on a daily basis: Contextual correlates and the link to work engagement. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 1120–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wingerden, J.; Derks, D.; Bakker, A.B. The Impact of Personal Resources and Job Crafting Interventions on Work Engagement and Performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 56, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The Conservation of Resources Model Applied to Work–Family Conflict and Strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Siu, O.; Spector, P.E.; Shi, K. Antecedents and outcomes of a fourfold taxonomy of work-family balance in Chinese employed parents. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2009, 14, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C.R.; Appelbaum, E.; Shevchuk, I. Work Process and Quality of Care in Early Childhood Education: The Role of Job Crafting. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Hirst, G.; Shipton, H. Context matters: Combined influence of participation and intellectual stimulation on the promotion focus-employee creativity relationship. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 33, 894–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Zhou, J. Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berdicchia, D.; Masino, G. The Ambivalent Effects of Participation on Performance and Job Stressors: The Role of Job Crafting and Autonomy. Hum. Perform. 2019, 32, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, A.; Krug, I.; Westrupp, E. Crossover of parents’ work-family conflict to family functioning and child mental health. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2019, 62, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Spector, P.E.; Shi, L. Cross-national job stress: A quantitative and qualitative study. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 209–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J. Multilevel structural equation models for assessing moderation within and across levels of analysis. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.D.H.N.; Luiz, A.J.B.; Campanhola, C. Statistical Inference on Associated Fertility Life Table Parameters Using Jackknife Technique: Computational Aspects. J. Econ. Entomol. 2000, 93, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollar, D.W. The Method of Path Coefficients. In Trajectory Analysis in Health Care; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W.M.; Schmitt, N. Parameter Recovery and Model Fit Using Multidimensional Composites: A Comparison of Four Empirical Parceling Algorithms. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 379–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandalos, D.L. The Effects of Item Parceling on Goodness-of-Fit and Parameter Estimate Bias in Structural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 78–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W.-J.; Oh, I. Effect of Work-Family Balance Policy on Job Selection and Social Sustainability: The Case of South Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J. Work-Family Facilitation and Conflict, Working Fathers and Mothers, Work-Family Stressors and Support. J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 793–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ozeki, C. Work-family conflict, policies, and the job-life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior-human resources research. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.M.; Matias, M.; Lopez, F.G.; Matos, P.M. Work-family conflict and enrichment: An exploration of dyadic typologies of work-family balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 109, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Daily job crafting and the self-efficacy – performance relationship. J. Manag. Psychol. 2014, 29, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant-Vallone, E.J.; Donaldson, S.I. Consequences of work-family conflict on employee well-being over time. Work Stress 2001, 15, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L.; Vansteenkiste, M. Autonomy and Autonomy Disturbances in Self-Development and Psychopathology: Research on Motivation, Attachment, and Clinical Process. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K. Review Article: How can we make organizational interventions work? Employees and line managers as actively crafting interventions. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 1029–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindfleisch, A.; Malter, A.J.; Ganesan, S.; Moorman, C. Cross-Sectional versus Longitudinal Survey Research: Concepts, Findings, and Guidelines. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böckerman, P.; Ilmakunnas, P. The Job Satisfaction-Productivity Nexus: A Study Using Matched Survey and Register Data. ILR Rev. 2012, 65, 244–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, S.; Lüdtke, O.; Robitzsch, A. Multiple Imputation of Missing Data for Multilevel Models. Organ. Res. Methods 2017, 21, 111–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertz, C.P.; Boyar, S.L.; Maloney, P.W.; Boya, S.L. A theory of work-family conflict episode processing. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 115, 103331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N.; Zhong, R.; Wang, X.; Tiong, R. Cross-domain negative effect of work-family conflict on project citizenship behavior: Study on Chinese project managers. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 36, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, L.M.; Li, Y.; Kwan, H.K.; Greenhaus, J.H.; DiRenzo, M.S.; Shao, P. A meta-analysis of the antecedents of work-family enrichment. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 39, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Education | 3.381 | 0.752 | |||||||||||

| 2. Income | 4.015 | 1.402 | 0.325 ** | ||||||||||

| 3. Gender | 1.411 | 0.493 | −0.009 | 0.325 ** | |||||||||

| 4. Age | 35.891 | 8.103 | −0.407 ** | 0.163 * | −0.254 ** | ||||||||

| 5. Children | 1.168 | 0.436 | −0.045 | −0.297 ** | 0.139 * | −0.089 | |||||||

| 6. Parent | 1.738 | 0.627 | 0.213 ** | 0.044 | 0.125 | −0.180 * | −0.001 | ||||||

| 7. Job autonomy | 3.777 | 0.730 | 0.147 * | 0.075 | −0.016 | −0.252 ** | −0.090 | −0.002 | (0.872) | ||||

| 8. WFC | 2.691 | 1.121 | 0.079 | 0.116 | −0.142 * | 0.094 | 0.152 * | 0.129 | −0.069 | (0.911) | |||

| 9. Job crafting | 3.795 | 0.334 | 0.132 | 0.135 | −0.069 | 0.057 | 0.017 | 0.014 | 0.270 ** | 0.045 | (0.887) | ||

| 10. PRF | 4.103 | 0.622 | −0.01 | 0.038 | −0.098 | 0.031 | 0.014 | 0.108 | 0.127 | 0.029 | 0.425 ** | (0.799) | |

| 11. SCP | 3.633 | 0.808 | −0.076 | 0.035 | −0.166 * | 0.033 | −0.086 | −0.007 | 0.176 * | 0.136 | 0.195 ** | 0.147 * | (0.902) |

| Variables | Job Crafting | Sustainable Creative Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Intercept | 2.634 *** | 2.641 *** | 2.783 *** | 2.807 *** | 3.736 *** | 2.640 ** |

| Education | 0.066 | 0.066 | 0.072 * | 0.077 * | −0.121 | −0.148 |

| Incoming | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.011 | −0.008 | −0.014 |

| Gender | −0.007 | −0.006 | 0.022 | 0.003 | −0.273 * | −0.270 * |

| Age | 0.008 * | 0.008 * | 0.007 * | 0.007 * | 0.000 | −0.004 |

| Children | 0.066 | 0.063 | 0.049 | 0.019 | −0.104 | −0.131 |

| Parent | 0.009 | 0.008 | −0.022 | −0.022 | 0.049 | 0.046 |

| Job automony | 0.137 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.111 *** | 0.120 *** | 0.205 * | 0.148 |

| Work-family conflict | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.001 | |||

| Promotion regulatory focus | 0.213 *** | 0.206 *** | ||||

| Int | 0.087 ** | |||||

| Job crafting | 0.416 ** | |||||

| ΔF | 3.820 ** | 0.043 | 39.177 *** | 8.496 ** | 2.178 * | 5.576 ** |

| R2 | 0.121 | 0.121 | 0.270 | 0.301 | 0.073 | 0.099 |

| ΔR2 | 0.149 | 0.031 *** | 0.031 ** | 0.026 ** | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Wang, F.; Das, A.K. Work–Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198004

Zhang M, Wang F, Das AK. Work–Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):8004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198004

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Man, Fan Wang, and Anupam Kumar Das. 2020. "Work–Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 8004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198004

APA StyleZhang, M., Wang, F., & Das, A. K. (2020). Work–Family Conflict on Sustainable Creative Performance: Job Crafting as a Mediator. Sustainability, 12(19), 8004. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198004