Elaboration of Social Media Performance Measures: From the Perspective of Social Media Discontinuance Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Quantifying Social Media Contributions: The Genuine Performance Measure

2.2. Importance of Social Media Discontinuance Behavior

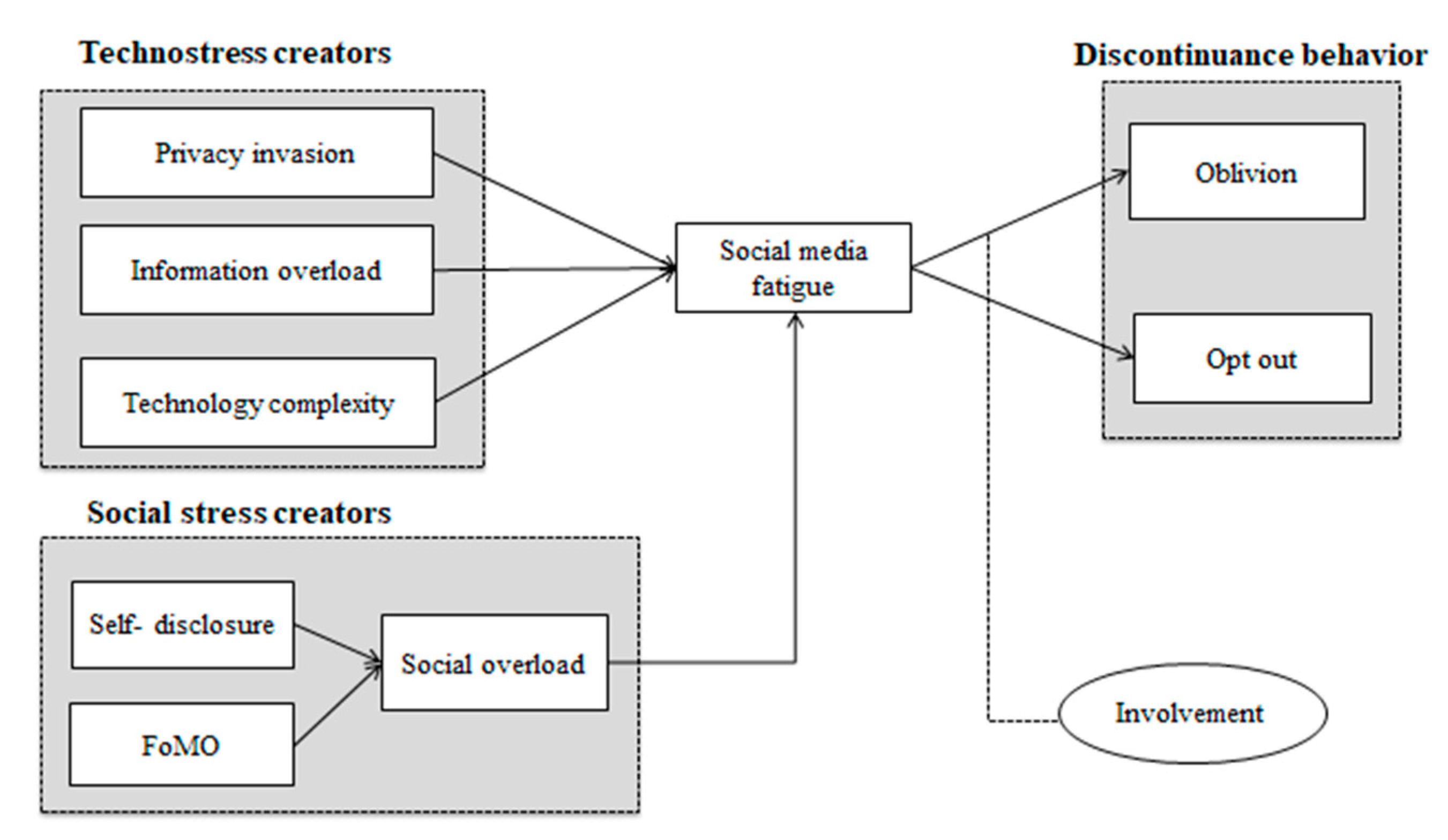

2.3. An Overall Process Driving Social Media Discontinuance Behavior

2.3.1. Social Media Fatigue Driving Discontinuance Behavior

2.3.2. Stressors Driving Social Media Fatigue

2.4. Social Media Involvement

2.5. Research Hypotheses

2.5.1. Technostress Creators and Social Media Fatigue

2.5.2. Socialstress Creators and Social Media Fatigue

2.5.3. Social Media Fatigue and Discontinuance Behavior

2.5.4. The Mediating Role of Involvement

3. Material and Method

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Constructs and Measurement Items

4. Results

4.1. Sample Characteristics and Correlations

4.2. Measurement and Validation

4.3. Empirical Results

4.4. The Mediating Effect of Social Media Involvement

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability Statement

References

- Learn BONDS. Available online: https://learnbonds.com/news/facebook-users-in-the-us-exceeded-70-of-its-entire-population/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1011415/south-korea-number-of-social-media-users-by-platform/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Hui, S.K. Understanding repeat playing behavior in casual games using a Bayesian data augmentation approach. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2017, 15, 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacka, E.; Chong, A. Usability perspective on social media sites’ adoption in the B2B context. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Feng, X.; Chen, P. Examining microbloggers’ individual differences in motivation for social media use. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2018, 46, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/05/americans-are-changing-their-relationship-with-facebook (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Moll, R.; Pieschl, S.; Bromme, R. Blessed oblivion? Knowledge and metacognitive accuracy in online social networks. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2015, 9, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Mou, J. Social media fatigue-Technological antecedents and the moderating roles of personality traits: The case of WeChat. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 101, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokouhyar, S.; Siadat, S.H.; Razavi, M.K. How social influence and personality affect users’ social network fatigue and discontinuance behavior. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 70, 344–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, A.; Yossatorn, Y.; Kaur, P.; Chen, S. Online social media fatigue and psychological wellbeing-A study of compulsive use, fear of missing out, fatigue, anxiety and depression. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 40, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Asghar, M.; Ahmad, H.; Kundi, F.; Ismail, S. A Rule-Based Sentiment Classification Framework for Health Reviews on Mobile Social Media. J. Med. Imaging Health Inform. 2017, 7, 1445–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Z.G.; Krieger, H.; LeRoy, A.S. Fear of missing out: Relationships with depression, mindfulness, and physical symptoms. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 2016, 2, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdough, C. Social media measurement: It’s not impossible. J. Interact. Advert. 2009, 10, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Fodor, M. Can you measure the ROI of your social media marketing? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010, 52, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Lee, M.K.; Hua, Z. A theory of social media dependence: Evidence from microblog users. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 69, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Du, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Ross, K.; Ghose, A. Broadcast yourself: Understanding YouTube uploaders. In Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement Conference, Berlin, Germany, 2–4 November 2011; pp. 361–370. [Google Scholar]

- Agostino, D. Using social media to engage citizens: A study of Italian municipalities. Public Relat. Rev. 2013, 39, 232–234. [Google Scholar]

- Huesch, M.D.; Galstyan, A.; Ong, M.K.; Doctor, J.N. Using social media, online social networks, and internet search as platforms for public health interventions: A pilot study. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 51, 1273–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Panyam, S.; Roby, F.; Mansukhani, S. Social Networking Relevance Index. U.S. Patent No. 8,930,453, 6 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Goldstein, N.J. Social Influence: Compliance and Conformity. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 2004, 55, 562–591. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran, T.; YeowKuan, A.C.; Hoe Lian, D.G. Antecedents and effects of social network fatigue. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 2306–2320. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, C.; Laumer, S.; Eckhardt, A.; Weitzel, T. When Social Networking Turns to Social Overload: Explaining the stress, Emotional Exhaustion, and Quitting Behavior from Social Network sites’ Users. Ecis 2014, 71, 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Turel, O.; He, Q.; Xue, G.; Xiao, L.; Bechara, A. Examination of neural systems sub-serving Facebook “addiction”. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 115, 675–695. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, X.J.; Radzol, A.M.; Cheah, J.; Wong, M.W. The impact of social media influencers on purchase intention and the mediation effect of customer attitude. Asian J. Bus. Res. 2017, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lui, Q.; Zhu, S.P.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Z.Y. Fatigue reliability assessment of turbine discs under multi-source uncertainties. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2018, 41, 1291–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, H.; Bao, T.; Shen, X.; Li, Q.; Seluzicki, C.; Im, E.O.; Mao, J.J. Prevalence and risk factors for fatigue among breast cancer survivors on aromatase inhibitors. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 101, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.L.; Cheung, C.M.; Lee, M.K. Perceived critical mass and collective intention in social media-supported group communication. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 33, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, L.B.; DeLuca, J.O.H.N. Fatigue: Its influence on cognition and assessment. Second. Influ. Neuropsychol. Test Perform. 2013, 19, 117–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Liu, H. Learning with Large-Scale Social Media Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guest Post. Facebook is Facing User Fatigue. Hyperbot. Available online: http://www.hypebot.com/hypebot/02/facebook-facing-user-fatigue.html (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Kelly, G.; Janssen, M.; Rana, N.P.; Slade, E.L.; Clement, M. Social Media: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Xu, S.X.; Zhang, N. Psychological ownership motivation and use of social media. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2015, 23, 185–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ragu-Nathan, T.S.; Tarafdar, M.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Tu, Q. The consequences of technostress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Son, S.M.; Kim, K.K. Information and communication technology overload and social networking service fatigue: A stress perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarafdar, M.; Tu, Q.; Ragu-Nathan, B.S.; Ragu-Nathan, T.S. The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Cao, X. The balancing mechanism of social networking overuse and rational usage. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karr Wisniewski, P.; Lu, Y. When more is too much: Operationalizing technology overload and exploring its impact on knowledge worker productivity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1061–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C. An empirical analysis of factors influencing continuance intention of mobile instant messaging in China. Inf. Develop. 2015, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Yang, J. Do you get tired of socializing? An empirical explanation of discontinuous usage behavior in social network services. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, S.; Padmanabhan, A.; Yin, J.; Cao, G. Mapping spatiotemporal patterns of events using social media: A case study of influenza trends. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 32, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazer, J.P.; Murphy, R.E.; Simonds, C.J. I’ll see you on Facebook: The Effects of Computer-Mediated Teacher Self-Disclosure on student Motivation, Affective Learning, and Classroom Climate. Commun. Educ. 2007, 56, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Why Americans Use Social Media: Social Networking Sites are Appealing as a Way to Maintain Contact with Close Ties and Reconnect with Old Friends. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2011/11/15/why-americans-use-social-media/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Casale, S.; Rugai, L.; Fioravanti, G. Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addict. Behav. 2018, 85, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T.L.; Lowry, P.B.; Wallace, L.; Warkentin, M. The effect of belongingness on obsessive-compulsive disorder in the use of online social networks. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2017, 34, 560–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, X.Y.; Bai, B. How motivation, opportunity, and ability impact travelers’ social media involvement and revisit intention. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putrevu, S. Consumer responses toward sexual and nonsexual appeals: The influence of involvement, need for cognition (NFC), and gender. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Gupta, I.C.; Totala, N.K. Social media usage, electronic word of mouth and purchase-decision involvement. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2017, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linda, H. Exploring customer brand engagement: Definition and themes. J. Strateg. Mark. 2011, 19, 555–573. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.; Dongping, H.; Wahab, A. Does culture matter in effectiveness of social media marketing strategy? An investigation of brand fan pages. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 68, 697–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Bao, Z. The role of negative network externalities in SNS fatigue: An empirical study based on impression management concern, privacy concern, and social overload. Data Technol. Appl. 2018, 52, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S. Disclosure intention of location-related information in location-based social network services. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 16, 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H. The effects of trust, security and privacy in social networking: A security-based approach to understand the pattern of adoption. Interact. Comput. 2010, 22, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Shin, M. To be connected or not to be connected? Mobile messenger overload, fatigue, and mobile shunning. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Stokols, D. Psychological and health outcomes of perceived information overload. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyagari, R.; Grover, V.; Purvis, R. Technostress: Technological antecedents and implications. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 831–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Barber, K.T. Self-disclosure and student satisfaction with Facebook. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 624–630. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey, D.W. The importance of ease of use, usefulness, and trust to online consumers: An examination of the technology acceptance model with older customers. J. Organ. End User Comput. (JOEUC) 2006, 18, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, L.; Wu, M. An integrated methodology for robustness analysis in feature fatigue problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 5985–5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maire, C.; Laumer, S.; Eckhardt A and Weitzel, T. Online social networks as a source and symbol of stress: An empirical analysis. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Information Systems, Orlando, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Animesh, A.; Pinsonneault, A.; Yang, S.B.; Oh, W. An odyssey into virtual worlds: Exploring the impacts of technological and spatial environments on intention to purchase virtual products. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, C.; Lowry, P.B.; Roberts, T.L.; Ellis, T.S. Proposing the online community self-disclosure model: The case of working professionals in France and the U.K.—Who uses online communities. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.E.; Gosling, S.D.; Graham, L.T. A review of Facebook research in the social sciences. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 7, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kankanhalli, A.; Tan, B.C.; Wei, K.K. Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, M.; Tanis, I. VermeulenIt is all about being popular. The effects of need for popularity on social network site use. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbaugh, E.; Ferris, A. Facebook self-disclosure: Examining the role of traits, social cohesion, and motives. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 20, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, A.K.; Murayama, K.; DeHaan, C.R.; Gladwell, V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osemeahon, O.S.; Agoyi, M. Linking FOMO and smartphone use to social media brand communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argan, M. Fomsumerism: A Theoretical Framework. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2018, 10, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberst, U.; Elisa, W.; Benjamin, S.; Matthias, B.; Abdres, C. Negative consequences from heavy social networking in adolescents: The mediating role of fear of missing out. J. Adolesc. 2017, 55, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, C.; Laumer, S.; Eckhardt, A.; Weitzel, T. Giving too much social support: Social overload on social networking sites. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 447–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; LePine, J.A.; LePine, M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błachnio, A.; Przepiórka, A. Facebook intrusion, fear of missing out, narcissism, and life satisfaction: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 259, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaouali, W. Once a user, always a user: Enablers and inhibitors of continuance intention of mobile social networking sites. Telemat. Inform. 2016, 33, 1022–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R. Living a private life in public social networks: An exploration of member self-disclosure. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 55, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, L.F.; Kleiser, S.B.; Grau, S.L. Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 44, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I.; Liu, C.C.; Chen, K. The Push, Pull and Mooring Effects in Virtual migration for Social Networking Sites. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiue, Y.C.; Chiu, C.M.; Chang, C.C. Exploring and mitigating social loafing in online communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Thompson, R.; Higgins, C. The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modelling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beyens, I.E.; Frison, S. Eggermont. “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, E.S.; Danilova, Y.S.; Bykov, A.Y.; Sergeevna, A.S.; Labush, N.S. Media systems of South-Eastern Europe in the condition of democratic transition: The example of Albania, Bulgaria, Macedonia and Serbia. Int. Rev. Manag. Mark. 2015, 6, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Seko, Y.; Lewis, S.P. The self—Harmed, visualized, and reblogged: Remaking of self-injury narratives on Tumblr. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 180–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fondevila-Gascón, J.F.; Polo-López, M.; Rom-Rodríguez, J.; Mir-Bernal, P. Social media Influence on consumer behavior: The case of mobile telephony manufacturers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimaitis, I.; Degutis, M.; Urbonavicius, S. Social media use and paranoid. Factors that matter in online shopping. Sustainability 2020, 12, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technopedia. Definition of Social Media Fatigue. 2011. Available online: https://www.techopedia.com/definition/27372/social-media-fatigue (accessed on 12 December 2019).

| Researchers | Social Media Quantified Contributions | Social Media Forms |

|---|---|---|

| [13] | number of visits, comment frequency | Social Networking (Facebook, Myspace) |

| [14] | number of tags, number of additional taggers | Social Tagging (StumbleUpon) |

| [15] | number of views of videos, number subscribers | Media Sharing (YouTube, Flickr) |

| [16] | number of members, number of return visit | Blogs (Blogspot) |

| [17] | number of retweets, number of “likes” | Microblogging (Twitter) |

| [18] | numbers of visitors, number of active users | Wikis (Wikipedia) |

| [19] | number of web clicks | Search engine (Google Search) |

| [3] | number of retweets, number of active users | Social Networking (Facebook) |

| Antecedents of Social Media Fatigue | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors | Techno Complexity | Social Overload | Information Overload | Invasion of Privacy | Invasion of Work | System Feature Overload | Depression | Anxiety |

| [22] | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| [39] | √ | √ | ||||||

| [35] | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| [40] | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| [11] | √ | √ | ||||||

| [37] | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| [41] | √ | √ | ||||||

| [10] | √ | √ | ||||||

| [41] | √ | √ | ||||||

| [9] | √ | √ | ||||||

| Constructs | Measurement Items | Researcher |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy invasion | I usually have this awkward feeling that using SNS can be monitored easily. | [37] |

| I often feel that my activities using SNS can be traced easily and, as such, my privacy will be compromised. | ||

| I often feel that my privacy using SNS can be breach by my employer via tracking my activities. | ||

| I often feel that social media makes me provide a lot of personal information. | ||

| Information overload | I think the huge amount of information available on social media often troubles me. | [39] |

| I usually feel that, on a daily basis, the quantity of information that I have to process on social media is overwhelming. | ||

| I usually discover that, while using social media, only a small part of the information is relevant to me. | ||

| I think there is lots of information on social media regarding my friends which is generally difficult for me to handle. | ||

| Technology complexity | In general, social media is difficult to control. | [72] |

| The features of the social media that I use are often more complicated than the tasks I have to do using these features. | ||

| Social media usually makes me feel that I have little control over my activities. | ||

| Self-disclosure | Generally, I have a detailed profile on social media. | [76] |

| Normally, I upload huge amounts of information about myself on social media. | ||

| Generally, I do not bother placing my personal information on social media. | ||

| My profile picture on social media usually tells a lot about me. | ||

| FoMO | Overall, I worry that social media gives rewarding experiences to users other than me. | [67] |

| Overall, I get worried knowing that my friends are having fun on social media without me. | ||

| Overall, not knowing what my friends are doing on social media makes me worried. | ||

| Overall, when I have a good time, I feel it is necessary to share my detailed information online. | ||

| Social overload | Usually when I am using social media, I tend to focus more on my friend’s post. | [40] |

| On social media, I usually show a lot of care towards my friends’ welfare. | ||

| While using social media, casual associates often send me friend requests. | ||

| Social media fatigue | Generally, when using social media, I feel exhausted. | [75] |

| Generally, I waste a huge amount of my time on social media. | ||

| Generally, using social media puts me under a lot of pressure. | ||

| Social media Involvement | When I learn of a new social media site, I will hastily invite my friends to join. | [79] |

| Usually, I log onto social media sites at least once a day. | ||

| This social media site’s ability to expand social relationships is better than other social media sites overall. | ||

| This social media site’s ability to share information is in a timely manner overall. | ||

| This social media site’s ability to manage social relationships is effective overall. | ||

| Oblivion | This social media site makes me think of decreasing my time of use, generally. | [80] |

| This social media site makes me want to use the service less frequently, in general. | ||

| This social media site no longer draws my interest overall. | ||

| Opt out | This social media site usually makes me regret choosing this service. | [77] |

| This social media site usually makes me want to unregister. | ||

| This social media site usually makes me want to use another social network site in the future. | ||

| This social media site makes me want to use it far less than today in the future, generally. |

| Item | Characteristics | Frequency | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 105 | 45.3% |

| Female | 127 | 54.7% | |

| Total | 232 | 100% | |

| Age | 20–29 | 72 | 31.1% |

| 30–39 | 94 | 40.5% | |

| 40–49 | 42 | 18.1% | |

| Over 50 | 24 | 10.3% | |

| Total | 232 | 100% | |

| Daily average social media access time | Less than 30 min | 25 | 10.7% |

| 30 min–1 h | 76 | 32.8% | |

| 1 h–3 h | 89 | 38.4% | |

| More than 3 h | 42 | 18.1% | |

| Total | 232 | 100% | |

| Occupation | Student | 117 | 50.5% |

| Officer | 62 | 26.6% | |

| Self-employed | 31 | 13.4% | |

| Others | 22 | 9.5% | |

| Total | 232 | 100% |

| Constructs | Privacy Invasion | Information Overload | Technology Complexity | Self-Disclosure | FoMO | Social Fatigue | Social Overload | Oblivion | Opt Out |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy Invasion | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Information Overload | 0.253 *** | 1.00 | |||||||

| Technology Complexity | 0.117 | 0.275 *** | 1.00 | ||||||

| Self-Disclosure | 0.038 | 0.022 | 0.059 | 1.00 | |||||

| FoMO | 0.076 | 0.033 | 0.076 | 0.075 | 1.00 | ||||

| Social Fatigue | 0.318 *** | 0.389 *** | 0.15 ** | 0.075 | 0.031 | 1.00 | |||

| Social Overload | 0.353 *** | 0.178 *** | 0.117 | 0.189 * | 0.129 ** | 0.325 *** | 1.00 | ||

| Oblivion | 0.267 *** | 0.257 *** | 0.113 | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.374 *** | 0.078 | 1.00 | |

| Opt Out | 0.232 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.076 | 0.016 | 0.294 *** | 0.043 | 0.637 *** | 1.00 |

| Mean | 2.851 | 2.597 | 2.517 | 2.491 | 2.460 | 2.550 | 2.807 | 2.495 | 1.951 |

| S.D. | 0.851 | 0.772 | 0.697 | 0.418 | 0.464 | 0.859 | 0.820 | 0.782 | 0.735 |

| Constructs | Items | Factor Loading | S.E. | Std. Loading | t-Value | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Privacy invasion | PI1 | 1.000 | - | 0.552 | - | 0.784 | 0.510 |

| PI2 | 1.173 | 0.105 | 0.763 | 11.193 *** | |||

| PI3 | 0.857 | 0.089 | 0.463 | 9.643 *** | |||

| PI4 | 0.787 | 0.101 | 0.305 | 7.820 *** | |||

| Information overload | IO1 | 1.000 | - | 0.320 | - | 0.850 | 0.600 |

| IO2 | 1.690 | 0.181 | 0.835 | 9.329 *** | |||

| IO3 | 1.668 | 0.179 | 0.828 | 9.325 *** | |||

| IO4 | 1.064 | 0.152 | 0.313 | 6.978 *** | |||

| Technology complexity | TC1 | 1.000 | - | 0.473 | - | 0.774 | 0.568 |

| TC2 | 2.193 | 0.476 | 1.091 | 4.610 *** | |||

| TC3 | 1.261 | 0.206 | 0.341 | 6.124 *** | |||

| Self-disclosure | SD1 | 1.000 | - | 0.385 | - | 0.882 | 0.660 |

| SD2 | 1.456 | 0.293 | 0.318 | 4.964 *** | |||

| SD3 | 1.849 | 0.346 | 0.552 | 5.342 *** | |||

| SD4 | 1.727 | 0.324 | 0.496 | 5.326 *** | |||

| FoMO | FM1 | 1.000 | - | 0.428 | - | 0.789 | 0.494 |

| FM2 | 1.507 | 0.377 | 0.345 | 3.993 *** | |||

| FM3 | 1.793 | 0.443 | 0.437 | 4.052 *** | |||

| FM4 | 1.351 | 0.340 | 0.332 | 3.976 ** | |||

| Social media fatigue | SF1 | 1.000 | - | 0.626 | - | 0.813 | 0.592 |

| SF2 | 0.996 | 0.091 | 0.597 | 10.906 *** | |||

| SF3 | 0.976 | 0.094 | 0.533 | 10.424 *** | |||

| Social overload | SS1 | 1.000 | - | 0.591 | - | 0.833 | 0.630 |

| SS2 | 1.115 | 0.105 | 0.825 | 10.583 *** | |||

| SS3 | 0.730 | 0.078 | 0.404 | 9.403 *** | |||

| Oblivion | OB1 | 1.000 | - | 0.690 | - | 0.855 | 0.597 |

| OB2 | 1.082 | 0.144 | 0.538 | 7.523 *** | |||

| OB3 | 0.559 | 0.110 | 0.553 | 5.083 *** | |||

| Opt out | OP1 | 1.000 | - | 0.692 | - | 0.927 | 0.763 |

| OP2 | 1.067 | 0.081 | 0.573 | 13.209 *** | |||

| OP3 | 1.219 | 0.070 | 0.870 | 17.449 *** | |||

| OP4 | 1.060 | 0.073 | 0.649 | 14.452 *** |

| Path | Coefficient | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Privacy invasion → Social media fatigue | 0.300 ** | Supported |

| H2 | Information overload → Social media fatigue | 0.388 *** | Supported |

| H3 | Technology complexity → Social media fatigue | 0.163 * | Supported |

| H4 | Self-disclosure → Social overload | 0.493 * | Supported |

| H5 | FoMO → Social overload | 0.579 ** | Supported |

| H6 | Social overload → Social media fatigue | 0.190 *** | Supported |

| H7 | Social media fatigue → Oblivion | 0.500 *** | Supported |

| H8 | Social media fatigue → Opt out | 0.340 *** | Supported |

| Equality Constraint Model: = 1201.209 (df = 728), = 1.650 (Δd.f = 1, p < 0.01) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path | Cross-Group Path Coefficient | Result | ||

| High Group | Low Group | |||

| Social media fatigue → Oblivion | 4.513 | 0.445 *** | 0.742 *** | Supported |

| Social media fatigue → Opt out | 4.232 | 0.336 *** | 0.414 *** | Supported |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kang, I.; Zhang, Y.; Yoo, S. Elaboration of Social Media Performance Measures: From the Perspective of Social Media Discontinuance Behavior. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197962

Kang I, Zhang Y, Yoo S. Elaboration of Social Media Performance Measures: From the Perspective of Social Media Discontinuance Behavior. Sustainability. 2020; 12(19):7962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197962

Chicago/Turabian StyleKang, Inwon, Yiya Zhang, and Sungjoon Yoo. 2020. "Elaboration of Social Media Performance Measures: From the Perspective of Social Media Discontinuance Behavior" Sustainability 12, no. 19: 7962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197962

APA StyleKang, I., Zhang, Y., & Yoo, S. (2020). Elaboration of Social Media Performance Measures: From the Perspective of Social Media Discontinuance Behavior. Sustainability, 12(19), 7962. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12197962