How Is Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Measured? Comparing Four Approaches for the EU

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Global Level

2.2. SDG Monitoring for the EU

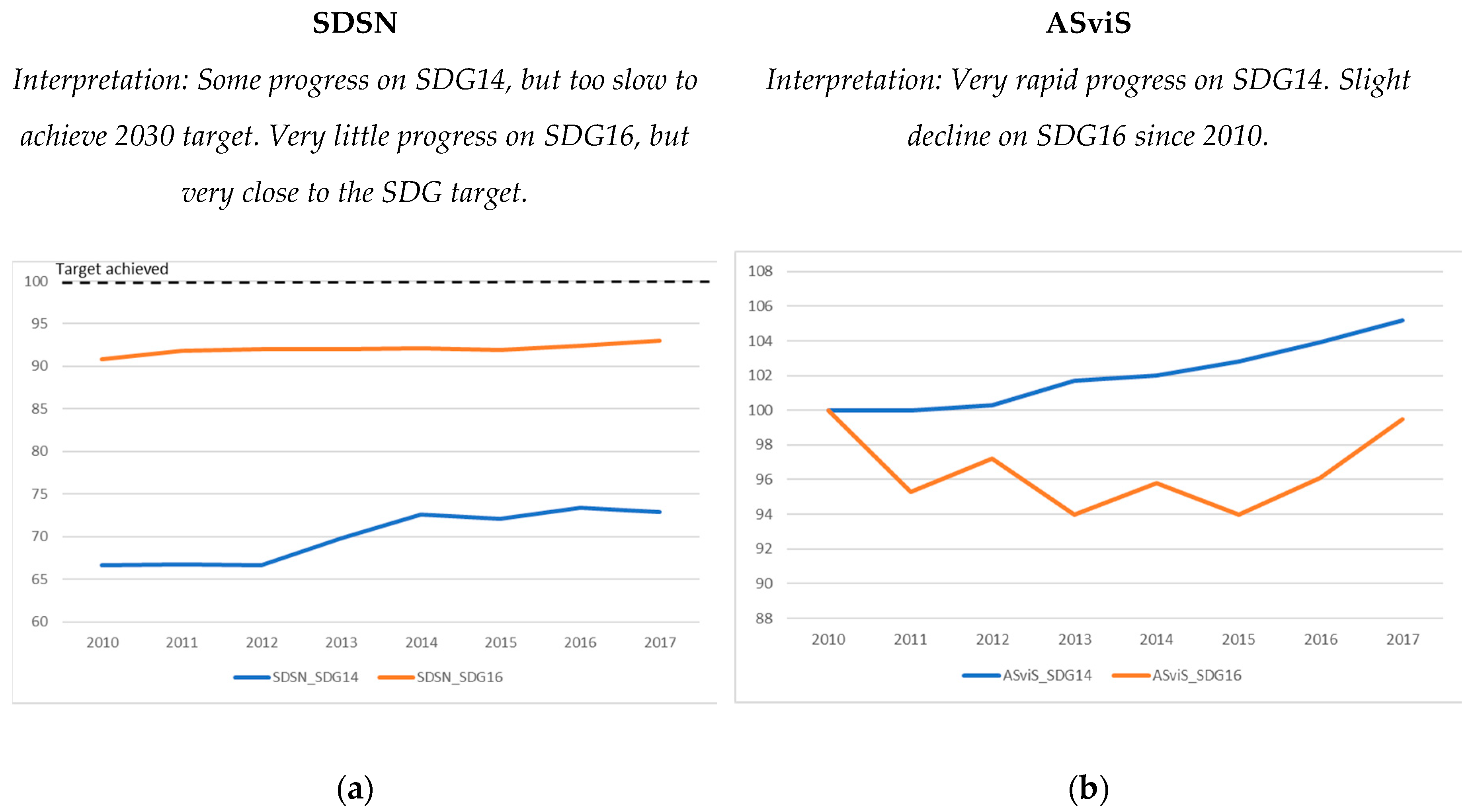

- Europe Sustainable Development Report [29]: Produced by the SDSN and IEEP, the report tracks the performance of all EU member states and the United Kingdom, as well as the European Union as a whole. It was released for the first time in 2019. It is based on a peer-reviewed and statistically audited methodology.

- Measuring Distance to SDG Targets 2019 [24]: Produced by the OECD in 2016, 2017, and 2019, the report tracks the performance of OECD countries on the SDGs. It calculates distance to targets and groups countries according to whether trends are moving in the right or wrong direction.

- Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the SDGs in an EU Context [27]: This report, produced by Eurostat every year since 2016, provides a snapshot of progress of the EU on the SDGs. Unlike the SDSN and OECD reports, it focuses only on trends over time rather than performance at one point in time. Individual indicators are presented for individual EU member states, but until the 2019 edition aggregate results at the goal level are only available at the level of the Union as a whole.

- Measuring the Situation of the European Union with regard to the SDGs [28]: Produced in 2019 by ASviS, the report tracks the progress of the EU on each of the SDGs using a subset of Eurostat’s SDG indicators covering the period 2010–2017. The year 2010 represents the reference value (equal to 100), while the evolution of the indicators shows the improvement (if the value rises) or the deterioration (if it falls) of the situation compared to the value for 2010.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Method

4. Results

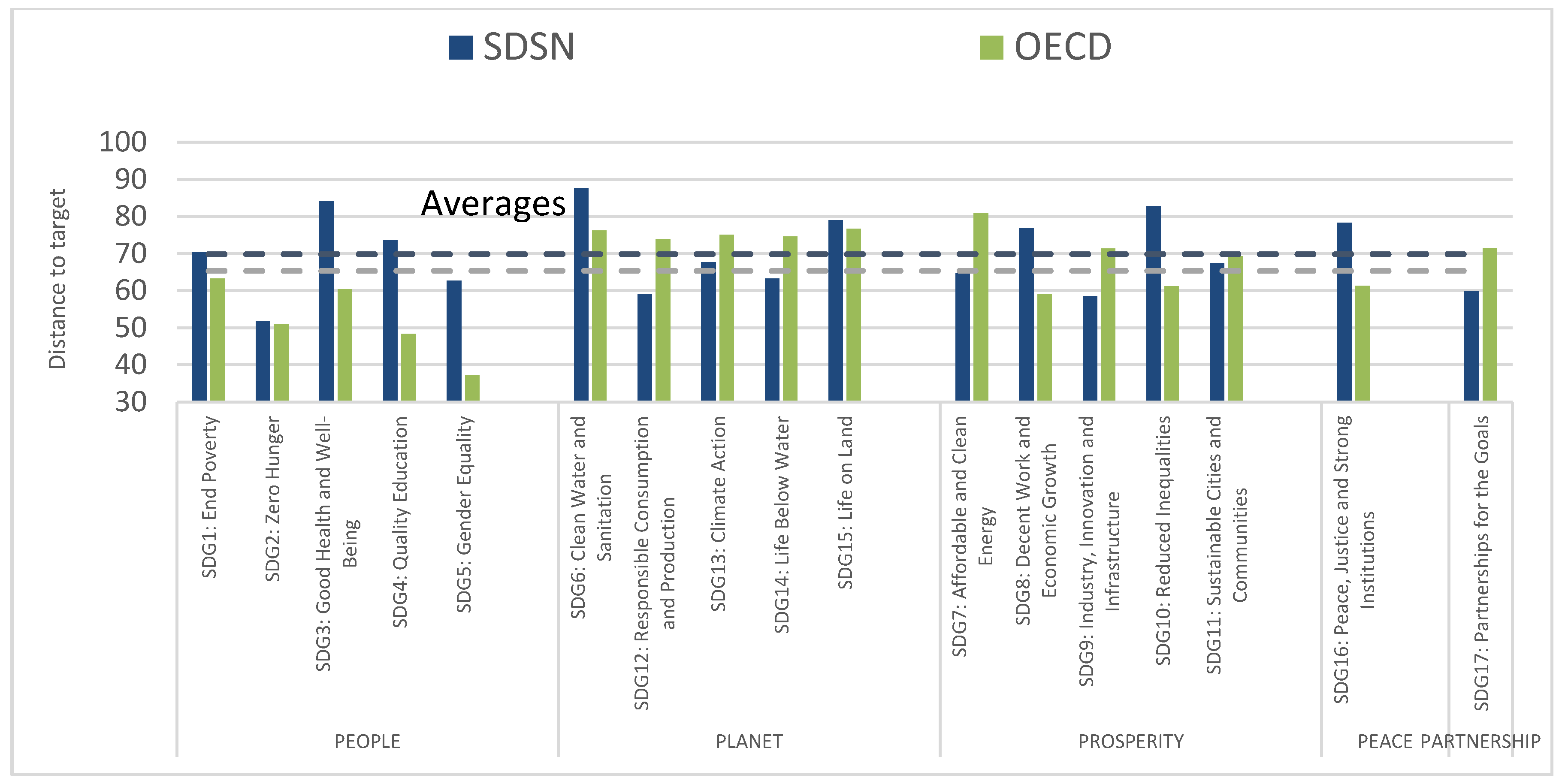

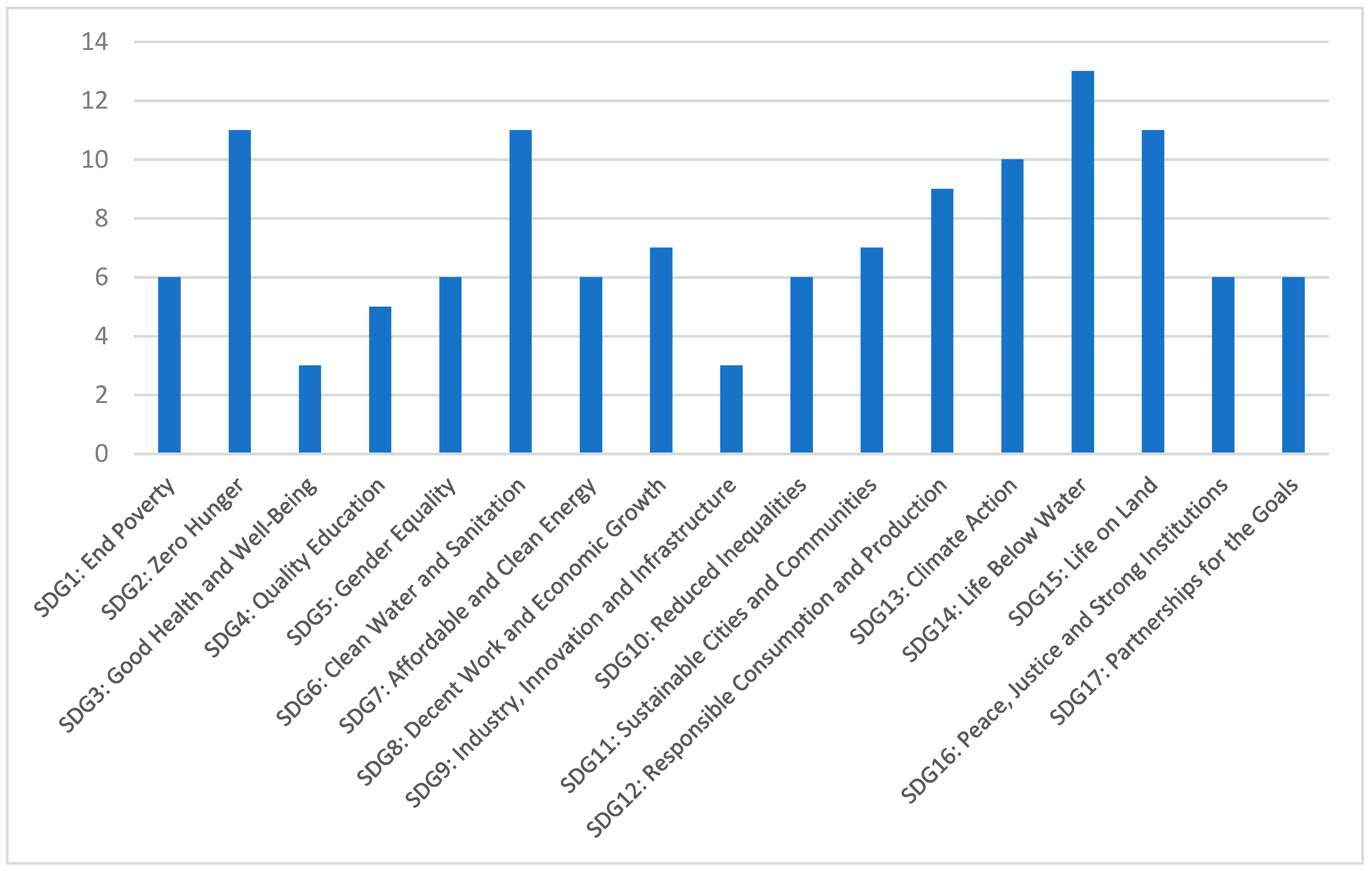

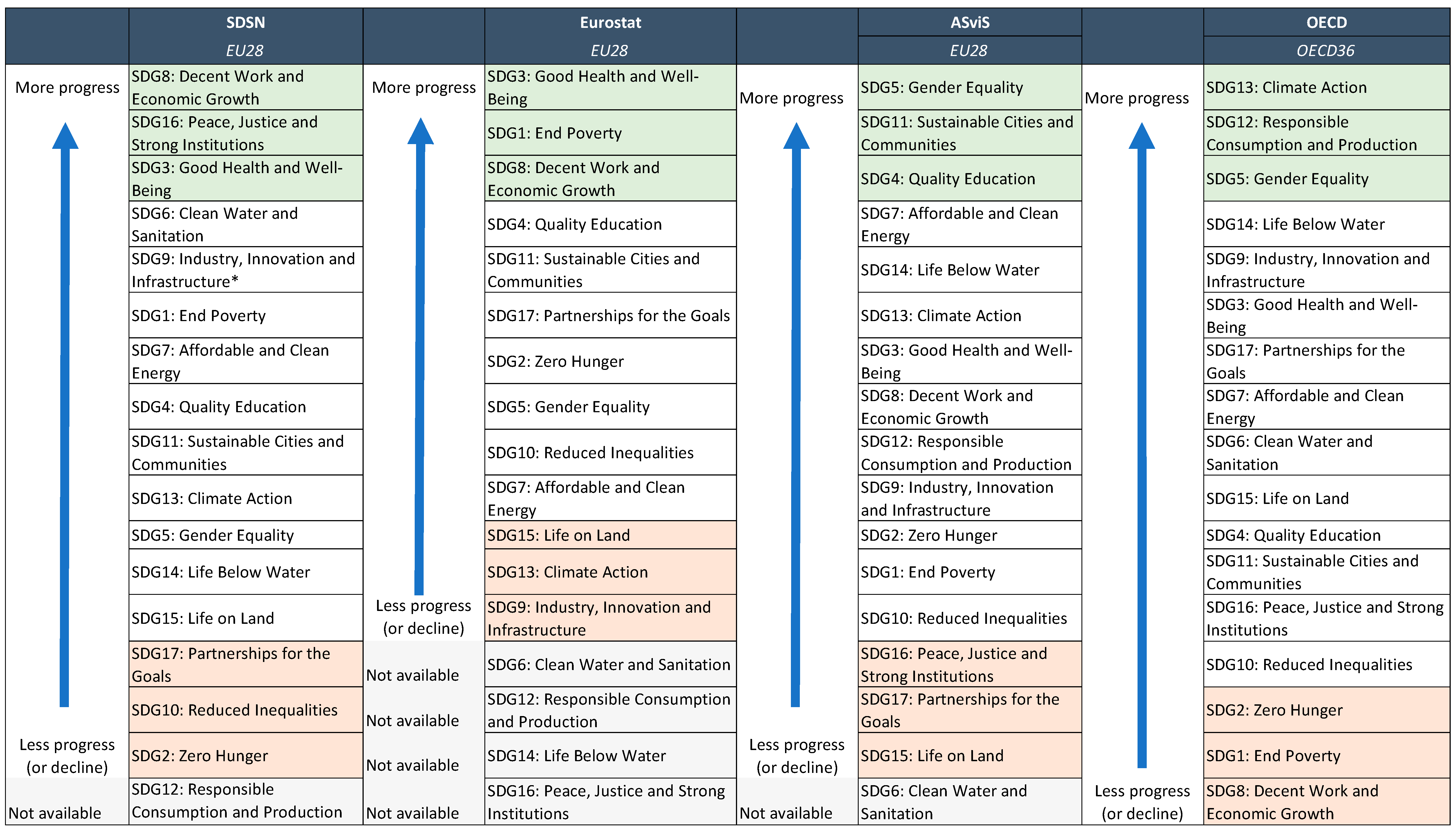

4.1. Overall Findings across the Four SDG Monitoring Instruments

4.2. Main Differences in Baseline Assessments

4.3. The Influence of Methodology Versus Indicator Selection in Baseline Assessments

4.4. The Impact of the Inclusion of Transboundary Impact Measures in Explaining Differences in Baseline Assessments for Environmental and Biodiversity Goals

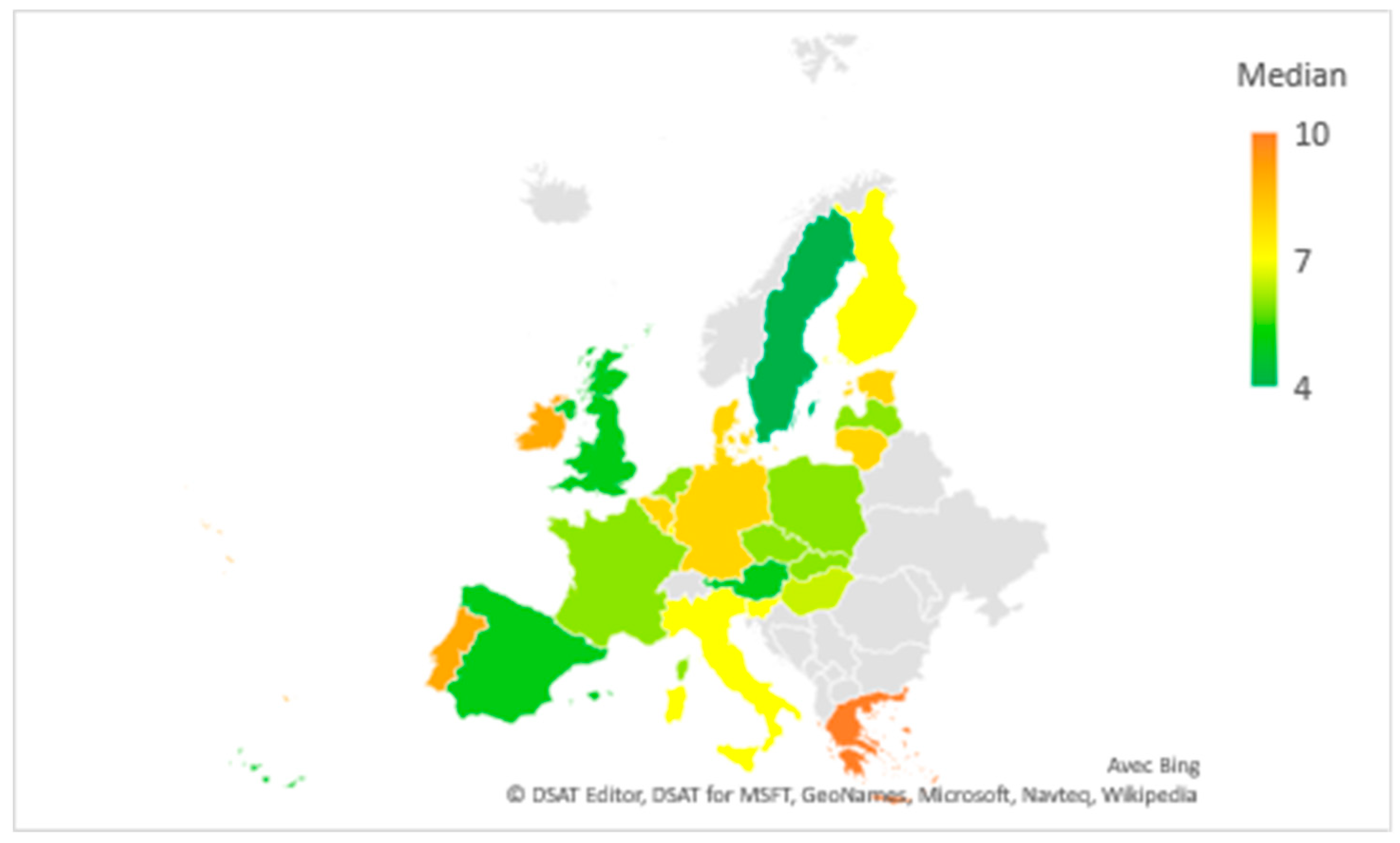

4.5. Interpreting Countries’ Trajectories

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stiglitz, J.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress; 2009; Available online: www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Brundtland, G. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; 1987; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Global Partnership for Poverty Eradication and Sustainable Development after 2015; 2015; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_15_4143 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- von der Leyen, U. A Union That Strives for More. My Agenda for Europe; 2019; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Council of the EU. Supporting the Sustainable Development Goals across the World: Council Adopts Conclusions. 2019. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/07/08/supporting-the-sustainable-development-goals-across-the-world-council-adopts-conclusions/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- European Commission. Communication COM/2019/640: The European Green Deal. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/european-green-deal-communication_en.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- European Commission. Just Transition Mechanism. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_930 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- European Commission. Remarks by Commissioner Gentiloni on EU Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_20_1141 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Teksoz, K.; Durand-Delacre, D.; Sachs, J.D. National baselines for the Sustainable Development Goals assessed in the SDG Index and Dashboards. Nature Geosci. 2017, 10, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inter-agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators. Global Indicator Framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and Targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2020. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; 2015; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- ECOSOC. Voluntary National Reviews Database. 2020. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/vnrs/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Simon, B.; Meyer, W.; D’Errico, S.; Schwandt, T.; Lucks, D.; Zhaoying, C.; El-Saddik, K.; Schneider, E.; Taube, L.; Anderson, S.; et al. Evaluation: A Missed Opportunity in the SDGs’ First Set of Voluntary National Reviews. 2017. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep17984 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Risse, N. Main Messages from 35 VNR Countries Outline SDG Actions and Plans|News|SDG Knowledge Hub|IISD. In IISD’s SDG Knowledge; 2018; Available online: https://sdg.iisd.org:443/news/main-messages-from-35-vnr-countries-outline-sdg-actions-and-plans/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Niklasson, L. Improving the Sustainable Development Goals: Strategies and the Governance Challenge; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNDESA. Sustainable Development Goals Progress Chart 2019. 2019. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/progress-chart.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Sachs, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Durand-Delacre, D.; Teksoz, K. SDG Index and Dashboards—Global Report; Bertelsmann Stiftung and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN): New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Durand-Delacre, D.; Teksoz, K. SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2017. Global Responsibilities—International Spillovers in Achieving the Goals; 2017; Available online: http://sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2018. Global Responsibilities. Implementing the Goals; 2018; Available online: http://sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. Sustainable Development Report 2019. Transformations to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals; 2019; Available online: http://sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- OECD. Measuring Distance to the SDGs Targets: A Pilot Assessment of Where OECD Countries Stand; 2016; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/std/measuring-distance-to-the-sdgs-targets.htm (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- OECD. Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets: An Assessment of Where OECD Countries Stand; 2017; Available online: http://www.oecd.org/std/OECD-Measuring-Distance-to-SDG-Targets.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- OECD. Measuring Distance to the SDG Targets 2019: An Assessment of Where OECD Countries Stand; 2019; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sdd/measuring-distance-to-the-sdg-targets-2019-a8caf3fa-en.htm (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Eurostat. Sustainable Development in the European Union—Monitoring Report on Progress towards the SDGs in an EU Context; 2017; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-04-17-780 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Eurostat. Sustainable Development in the European Union: Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the SDGs in An EU Context (2018 Edition); 2018; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/9237449/KS-01-18-656-EN-N.pdf/2b2a096b-3bd6-4939-8ef3-11cfc14b9329 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Eurostat. Sustainable Development in the European Union: Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the SDGs in An EU Context (2019 Edition); 2019; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-02-19-165 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- ASviS. The European Union and the Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: https://asvis.it/public/asvis2/files/Pubblicazioni/Compositi_Europei_ENG_HR.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- SDSN & IEEP. 2019 Europe Sustainable Development Report; 2019; Available online: https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/2019-europe-sustainable-development-report/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Costanza, R.; Daly, L.; Fioramonti, L.; Giovannini, E.; Kubiszewski, I.; Mortensen, L.F.; Pickett, K.E.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Modelling and measuring sustainable wellbeing in connection with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 130, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Matthews, Z.; Szabo, S.; Fogstad, H. Measuring the SDGs: A two-track solution. Lancet 2015, 386, 221–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE; OECD; Eurostat. Measuring sustainable development: Report of the Joint UNECE/OECD/Eurostat Working Group on Statistics for Sustainable Development. 2008. Available online: https://www.unece.org/stats/groups/wgssd.tor.html (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Holden, E.; Linnerud, K.; Banister, D. Sustainable development: Our Common Future revisited. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE. Conference of European Statisticians Recommendations on Measuring Sustainable Development. 2014. Available online: https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/publications/2013/CES_SD_web.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- McArthur, J.W.; Rasmussen, K. Change of pace: Accelerations and advances during the Millennium Development Goal era. World Dev. 2018, 105, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indicateurs Pour le Suivi National des Objectifs de Développement Durable|Insee. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2654964 (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- German Indicators for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment-germany.github.io/en/guidance/ (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- Lafortune, G.; Zoeteman, K.; Mulder, R.; Dagevos, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G. SDG Index and Dashboards Report for European Cities; 2019; Available online: https://www.sdgindex.org/reports/sdg-index-and-dashboards-report-for-european-cities/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- OECD. A Territorial Approach to the Sustainable Development Goals: Synthesis Report; 2020; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/a-territorial-approach-to-the-sustainable-development-goals-e86fa715-en.htm (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- WBCSD. SDG Sector Roadmaps: How to Leverage the Power of Sectoral Collaboration to Maximize Business Impact on the Sustainable Development Goals. 2018. Available online: https://www.wbcsd.org/Programs/People/Sustainable-Development-Goals/SDG-Sector-Roadmaps/Resources/SDG-Sector-Roadmaps (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- WBA. Climate and Energy Benchmark: Measuring the World’s 25 Most Influential Auto Manufacturers. 2019. Available online: https://www.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/measuring-the-worlds-25-most-influential-auto-manufacturers/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Gold Standard. Guidance for the Identification of Impacts and Indicators for Activity Level SDG Impact Reporting. 2019. Available online: https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/6f2c9f57/files/uploaded/2019_sdg_tool_guidance_briefing.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2020).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Woelm, F. Sustainable Development Report 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals and Covid-19; 2020; Available online: http://sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- IAEG-SDGs. Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; 2016; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/47th-session/documents/2016-2-IAEG-SDGs-Rev1-E.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- IAEG-SDGs. Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; 2020; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/statcom/51st-session/documents/2020-2-SDG-IAEG-E.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- IAEG-SDGs. Tier Classification for Global SDG Indicators as of 17 July 2020; 2020; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/Tier%20Classification%20of%20SDG%20Indicators_17%20July%202020_web.v2.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2020).

- SDSN. Indicators and a Monitoring Framework for Sustainable Development Goals: Launching a Data Revolution for the SDGs; 2015; Available online: http://unsdsn.org/resources/publications/indicators/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- United Nations. Informal Note for Statistical Commission Agenda Item 3 (a) Data in Support of the Post 2015 Development Agenda (i) Broader Measures of Progress. 2015. Available online: https://undocs.org/E/CN.3/2015/2 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D.; Castro-Fresno, D. Is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) index an adequate framework to measure the progress of the 2030 Agenda? Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Runting, R.K.; Venter, O.; Watson, J.E.M.; Carrasco, L.R. Environmental destruction not avoided with the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafortune, G.; Schmidt-Traub, G. Exposing EU Policy Gaps to Address the Sustainable Development Goals; 2019; Available online: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/en/our-work/publications-other-work/publications/exposing-eu-policy-gaps-address-sustainable-development-goals-study (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- OECD & JRC. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD, Joint Research Centre: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Treaty of Lisbon: Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community. 2007. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12007L%2FTXT (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Copernicus. How does Copernicus Support the UN Sustainable Development Goals? 2018. Available online: https://www.copernicus.eu/en/news/news/how-does-copernicus-support-un-sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 12 September 2020).

- European Commission. Reflection Paper: Towards a sustainable Europe by 2030. 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/rp_sustainable_europe_30-01_en_web.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- SDG Watch Europe. Not Fit for Purpose: SDG Monitoring Report Fails to Illustrate How Far the EU is from a Sustainable Future. 2017. Available online: https://www.sdgwatcheurope.org/not-fit-for-purpose-sdg-monitoring-report-fails-to-illustrate-how-far-the-eu-is-from-a-sustainable-future/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- SDG Watch Europe. 2019 Europe Sustainable Development Report—SDG Watch Europe; 2019; Available online: https://www.sdgwatcheurope.org/2019-europe-sustainable-development-report/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- SDG Watch Europe. Who is Paying the Bill; 2019; Available online: https://www.sdgwatcheurope.org/who-is-paying-the-bill/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Hickel, J. The sustainable development index: Measuring the ecological efficiency of human development in the anthropocene. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miola, A.; Schiltz, F. Measuring sustainable development goals performance: How to monitor policy action in the 2030 Agenda implementation? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Land is a Critical Resource, IPCC Report Says. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/2019/08/08/land-is-a-critical-resource_srccl/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. 2019. Available online: https://ipbes.net/global-assessment (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Cling, J.-P.; Eghbal-Teherani, S.; Orzoni, M.; Plateau, C. The Difference between EU Countries for Sustainable Development Indicators: It is (Mainly) the Economy! 2019. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/nsedoctra/g2019-06.htm (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Moreno, J.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C. SDG Index and Dashboards. Detailed Methodological Paper; 2018; Available online: http://sdgindex.org/assets/files/2018/Methodological%20Paper_v1_gst_jmm_Aug2018_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- Schmidt-Traub, G.; Hoff, H.; Bernlöhr, M. International Spillovers and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Measuring How a Country’s Progress towards the SDGs is Affected by Actions in other Countries; 2019; Available online: https://irp-cdn.multiscreensite.com/be6d1d56/files/uploaded/SDSN-Policy-Brief_International-spillovers-and-the-SDGs.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Weitz, N.; Carlsen, H.; Nilsson, M.; Skanberg, K. Towards systemic and contextual priority setting for implementing the 2030 Agenda. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesregierung. Deutsche Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie. Aktualisierung 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/975292/1559082/a9795692a667605f652981aa9b6cab51/deutsche-nachhaltigkeitsstrategie-aktualisierung-2018-download-bpa-data.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- FINGO. Policy Recommendations for the EU: Wellbeing and Sustainability at the Centre of Policy and Decision-Making. 2019. Available online: https://www.fingo.fi/sites/default/tiedostot/beyond-growth-recommendations_0.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Lenzen, M.; Moran, D.; Kanemoto, K.; Foran, B.; Lobefaro, L.; Geschke, A. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature 2012, 486, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzen, M.; Moran, D.; Kanemoto, K.; Geschke, A. Building Eora: A global multi-region input—Output database at high country and sector resolution. Econ. Syst. Res. 2013, 25, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Paredes, J.; Malik, A. Tracking the Sustainable Development Goals with Input-Output Analysis: A Commentary and Example. 2018. Available online: https://www.iioa.org/conferences/26th/papers/files/3409_Gmez-ParedesandMalik(2018)TrackingtheSustainableDevelopmentGoalswithInput-OutputAnalysis.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Malik, A.; McBain, D.; Wiedmann, T.O.; Lenzen, M.; Murray, J. Advancements in Input-Output Models and Indicators for Consumption-Based Accounting. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agardy, T.; di Sciara, G.N.; Christie, P. Mind the gap: Addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Mar. Policy 2011, 35, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, R.; Buxton, C.D.; Farebrother, G. Australia’s no-take marine protected areas: Appropriate conservation or inappropriate management of fishing? Mar. Policy 2012, 36, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Action Tracker. Some Progress since Paris, but not Enough, as Governments Amble towards 3 °C of Warming. 2018. Available online: https://climateanalytics.org/publications/2018/some-progress-since-paris-but-not-enough-as-governments-amble-towards-3c-of-warming/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six Transformations to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C. Sustainable Development Goals: Are the Rich Countries Ready? 2015; Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/sustainable-development-goals-are-the-rich-countries-ready/ (accessed on 15 August 2020).

| Organization | Report Title | Latest Edition | Number of Indicators | Number of EU Countries Covered | Includes Baseline Assessment (“Static”) | Includes Assessment of Countries’ Trajectories (“Dynamic”) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDSN | Europe Sustainable Development Report | 2019 | 113 | 28 | Yes | Yes |

| OECD | Measuring Distance to SDG Targets | 2019 | 132 | 23 | Yes | Yes |

| Eurostat | Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context | 2019 | 99 * | 28 | No | Yes |

| Asvis | Measuring the situation of the European Union with regard to the SDGs | 2020 | 77 | 28 | No | Yes |

| Organization | Pre-Defined Targets to Achieve by 2030 | Years Covered | EU Aggregate | N° of Trend Categories | Trend Categories | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDSN | Yes | 2015 to 2018 * | EU27 | 5 | On track or maintaining SDG achievement | Moderately improving | Stagnating | Decreasing | Data unavailable |

| OECD | Yes | 2005 to 2017 | None. Covers 23 EU member states. | 3 | Progress towards SDG target | Movement away from SDG target | No identified trend or not enough data | ||

| Eurostat | Partly | 2003 to 2018 (long term) and 2013 to 2018 (short term) ** | EU28 | 5 | Significant progress towards SD objectives **** | Moderate progress towards SD objectives | Moderate movement away from SD objectives | Significant movement away from SD objectives | Calculation of trend not possible (for example, time series too short) |

| ASviS | No | 2010 to 2017 | EU28 *** | Not applicable | Continuous trend 2010 to 2017 | ||||

| Scenario 1: Basic Adjustment | Scenario 2: Moderate Adjustment | Scenario 3: High Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| SDSN | OECD | Eurostat | ASviS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDSN | 1.00 | |||

| OECD | 0.07 | 1.00 | ||

| Eurostat | 0.66 | 0.18 | 1.00 | |

| ASviS | 0.72 | 0.17 | 0.91 | 1.00 |

| SDSN | OECD | Eurostat | ASviS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDSN | 1.00 | |||

| OECD | 0.06 | 1.00 | ||

| Eurostat | 0.60 | 0.39 | 1.00 | |

| ASviS | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.95 | 1.00 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Kroll, C. How Is Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Measured? Comparing Four Approaches for the EU. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187675

Lafortune G, Fuller G, Schmidt-Traub G, Kroll C. How Is Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Measured? Comparing Four Approaches for the EU. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187675

Chicago/Turabian StyleLafortune, Guillaume, Grayson Fuller, Guido Schmidt-Traub, and Christian Kroll. 2020. "How Is Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Measured? Comparing Four Approaches for the EU" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187675

APA StyleLafortune, G., Fuller, G., Schmidt-Traub, G., & Kroll, C. (2020). How Is Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals Measured? Comparing Four Approaches for the EU. Sustainability, 12(18), 7675. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187675