The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Achievement Goals in University Students: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Defensive Pessimism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Esteem and Achievement Goals

1.2. The Need to Protect Self-Worth: The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Defensive Pessimism

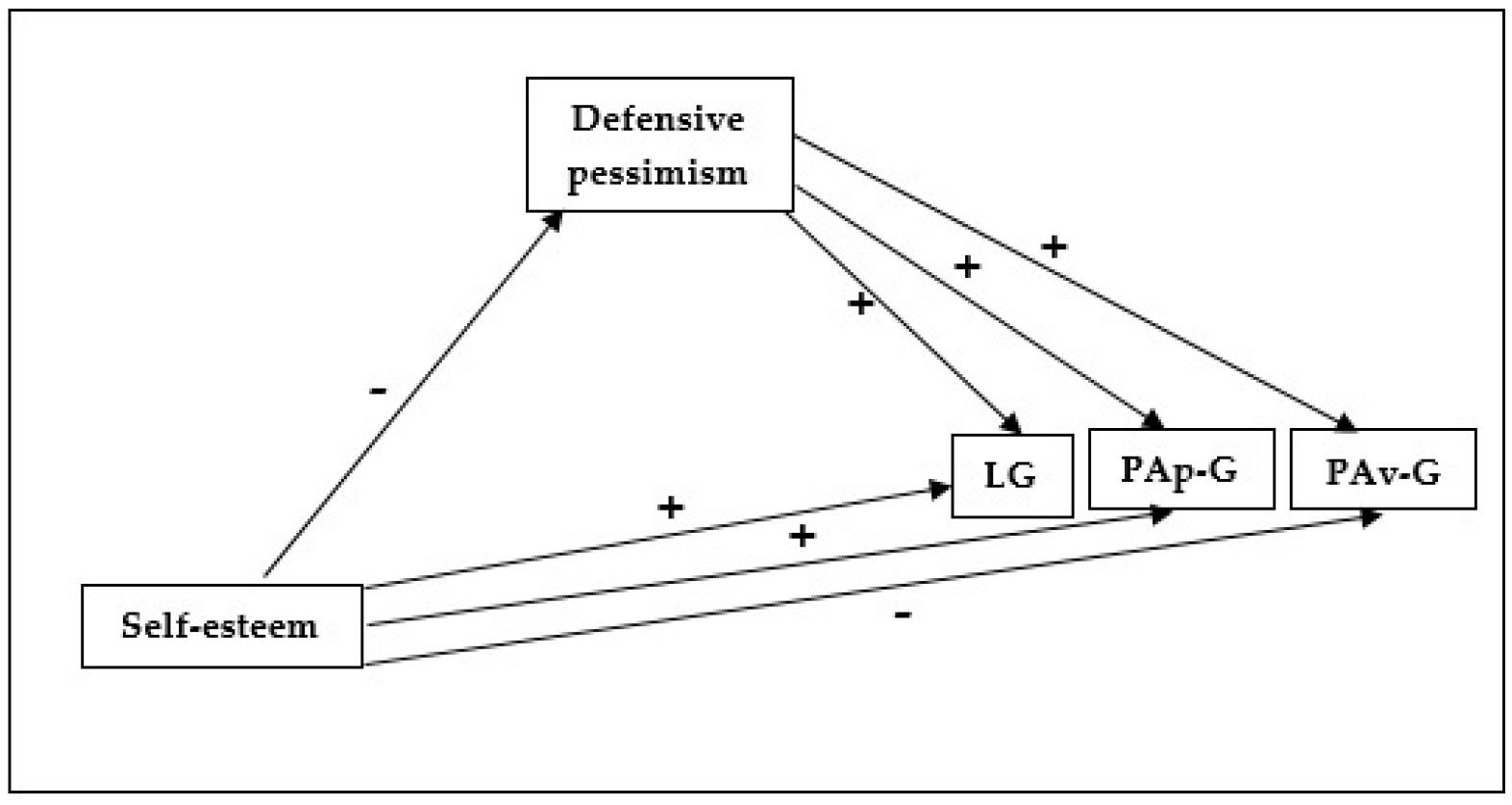

1.3. Self-Esteem, Defensive Pessimism, and Achievement Goals

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Analysis of Correlations

3.2. Analysis of Mediation

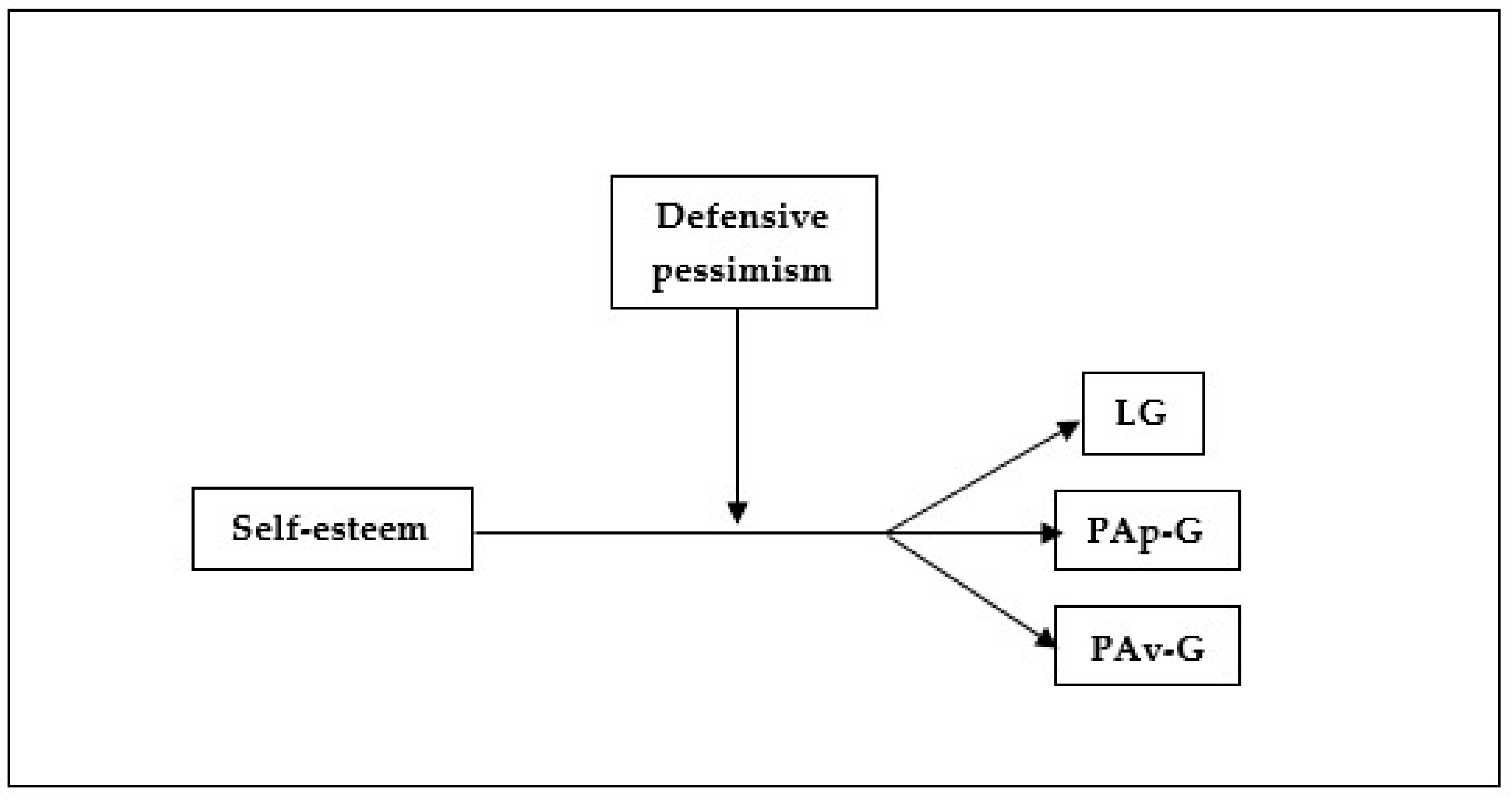

3.3. Analysis of Moderation

4. Discussion

4.1. Psycho-Educational and Health Implications

4.2. Limitations of the Study and Future Lines of Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Fabio, A. The psychology of sustainability and sustainable development for well-being in organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorsky, M.R.; Kofler, M.J.; Burns, G.L.; Luebbe, A.M.; Garner, A.A.; Jarrett, M.A.; Soto, E.F.; Becker, S.P. Factor structure and criterion validity of the five Cs model of positive youth development in a multi-university sample of college students. J. Youth Adolesc. 2019, 48, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savickas, M.L.; Porfeli, E.J. Career adaptabilities scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senko, C. Achievement goal theory: A story of early promises, eventual discords, and future possibilities. In Handbook of Motivation at School; Wentzel, K., Miele, D., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C.S.; Leggett, E.L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 95, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J. Approach and avoidance motivation and achievement goals. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 34, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.; Maehr, M.L. The contributions and prospects of goal orientation theory. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 19, 141–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; McGregor, H.A. A 2x2 achievement goal framework. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhadabi, A.; Karpinski, A.C. Grit, self-efficacy, achievement orientation goals, and academic performance in University students. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.; Larose, S.; Feng, B. Achievement goals and engagement with academic work in early high school: Does seeking help from teachers matter? J. Early Adolesc. 2019, 39, 222–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, S.; Ratelle, C.F. Achievement goals, motivations, and social and emotional adjustment in high school: A longitudinal mediation test. Educ. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadon, L.; Babenko, O.; Chazan, D.; Daniels, L.M. Burning out before they start? An achievement goal theory perspective on medical and education students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yperen, N.W.; Blaga, M.; Postmes, T. A meta-analysis of the impact of situationally induced achievement goals on task performance. Hum. Perform. 2015, 28, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Yperen, N.W.; Elliot, A.J.; Anseel, F. The influence of mastery-avoidance goals on performance improvement. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 39, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senko, C.; Dawson, B. Performance-approach goal effects depend on how they are defined: Meta-analytic evidence from multiple educational outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 574–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.B.; Mendoza, N.B. Achievement goal contagion: Mastery and performance goals spread among classmates. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2020, 23, 795–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Sanz, V.; Piqueras, J.A.; Rodríguez-Marín, J.; Pérez-Vázquez, M.T.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, T.; Castellví, P.; Miranda-Mendizábal, A.; Parés-Badell, O.; Almenara, J.; Blasco, M.J.; et al. Self-esteem and suicidal behavior in youth: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psicothema 2019, 31, 246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Reason, R.D.; Terenzini, P.T.; Domingo, R.J. First things first: Developing academic competence in the first year of college. Res. High. Educ. 2006, 47, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, G.; Cheng, Z. How social support influences university students’ academic achievement and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of self-esteem. Learn. Indiv. Differ. 2018, 61, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topçu, S.; Leana-Taşcılar, M.Z. The role of motivation and self-esteem in the academic achievement of Turkish gifted students. Gift. Educ. Int. 2018, 34, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L. Educational aspirations of Chinese migrant children: The role of self-esteem contextual and individual influences. Learn. Indiv. Differ. 2016, 50, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrotheodoros, S.; Talias, M.A.; Motti-Stefanidi, F. Goal orientation profiles, academic achievement and well-being of adolescents in Greece. In Well-Being of Youth and Emerging Adults Across Cultures. CROSS-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology; Dimitrova, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 105–120. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, A.M.; Reindl, M.; Grassinger, R.; Berner, V.D.; Dresel, R. Development of achievement goals across the transition out of secondary school. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2013, 61, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuominen-Soini, H.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Niemivirta, M. Achievement goal orientations and subjective well-being: A person-centred analysis. Learn. Instr. 2008, 18, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sun, K.; Wang, K. Self-Esteem, achievement goals, and self-handicapping in college physical education. Psychol. Rep. 2018, 121, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gębka, B. Psychological determinants of university students’ academic performance: An empirical study. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2014, 38, 813–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heimpel, S.A.; Elliot, A.J.; Wood, J.V. Basic personality dispositions, self-esteem, and personal goals: An approach-avoidance analysis. J. Pers. 2006, 74, 1293–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarraju, M.; Dial, C. Academic identity, self-efficacy, and self-esteem predict self-determined motivation and goals. Learn. Indiv. Differ. 2014, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, H.P. Students’ academic performance and various cognitive processes of learning: An integrative framework and empirical analysis. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.S.; Ryan, A.M.; Cassady, J. Changes in self-esteem across the first year in college: The role of achievement goals. Educ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkalp, Z.K. Achievement goals and physical self-perceptions of adolescent athletes. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2012, 40, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E.M. Self-enhancing and self-defeating ego orientation: Relations with task avoidance orientation, achievement, self-perceptions, and anxiety. J. Educ. Psychol. 1997, 89, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.D.; Yan Ho, W.K.; Van Niekerk, R.L.; Morris, T.; Elayaraja, M.; Lee, K.-C.; Randles, E. The self-esteem, goal orientation, and health-related physical fitness of active and inactive adolescent students. Cogent Psychol. 2017, 4, 1331602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Buckingham, J.T. Self–esteem as a moderator of the effect of social comparison on women’s body image. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 1164–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covington, M.V. Making the Grade: A Self-Worth Perspective on Motivation and School Reform; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Castella, K.; Byrne, D.; Covington, M.V. Unmotivated or motivated to fail? A cross-cultural study of achievement motivation, fear of failure, and student disengagement. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norem, J.K. Defensive pessimism as a self-critical tool. In Self-Criticism and Self-Enhancement: Theory, Research and Clinical Applications; Chang, E.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.J.; Marsh, H.W.; Williamson, A.; Debus, R.L. Self- handicapping, defensive pessimism and goal orientation: A qualitative study of university students. J. Educ. Psychol. 2003, 95, 617–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norem, J.K. Defensive pessimism, optimism, and pessimism. In Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice; Chang, E.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Seery, M.; West, T.; Weisbuch, M.; Blascovich, J. The effects of negative reflection for defensive: Dissipation or harnessing of threat? Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2008, 45, 515–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nob, R.M.; Bumanglag, A.M.L.; Diwa, G.M.; Ponce, G.I. The moderating role of defensive pessimism in the relationship between test anxiety and performance in a licensure examination. Educ. Meas. Eval. Rev. 2018, 9, 68–83. [Google Scholar]

- Norem, J.K.; Chang, E.C. A very full glass: Adding complexity to our thinking about the implications and applications of optimism and pessimism research. In Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice; Chang, E.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Tice, D.M.; Hutton, D.G. Self-presentational motivations and personality differences in self-esteem. J. Pers. 1989, 57, 547–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tice, D.M. Esteem protection or enhancement? Self-handicapping motives and attributions differ by trait self-esteem. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 711–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eronen, S.; Nurmi, J.; Salmela-Aro, K. Optimistic, defensive pessimistic, impulsive, and self-handicapping strategies in university environments. Learn. Instr. 1998, 8, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N.; Tschanz, B.T.; Feick, D.L. Defensive pessimism, self-esteem instability and goal strivings. Cogn. Emot. 2004, 18, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferradás, M.M.; Freire, C.; Núñez, J.C.; Regueiro, B. Associations between profiles of self-esteem and achievement goals and the protection of self-worth in university students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Marsh, H.W. Fear of failure: Friend or foe? Aust. Psychol. 2003, 38, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, A.J.; Church, M. A motivational analysis of defensive pessimism and self-handicapping. J. Pers. 2003, 71, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferradás, M.M.; Freire, C.; Regueiro, B.; Valle, A. Defensive pessimism, self-esteem and achievement goals: A person-centered approach. Psicothema 2018, 30, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, S.; Cabanach, R.G.; Valle, A.; Núñez, J.C.; González-Pienda, J.A. Differences in use of self-handicapping and defensive pessimism and its relation with achievement goals, self-esteem, and self-regulation strategies. Psicothema 2004, 16, 625–631. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Albo, J.; Núñez, J.L.; Navarro, J.G.; Grijalvo, F. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: Translation and validation in university students. Span. J. Psychol. 2007, 10, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norem, J.K. El Poder Positivo del Pensamiento Negativo: Utiliza el Pesimismo Defensivo para Reducir tu Ansiedad y Rendir al Máximo [The Positive Power of Negative Thinking: Using Defensive Pessimism to Harness Anxiety and Perform at Your Peak]; Paidos: Barcelona, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jover, I.; Navas, L.; Holgado, F.P. Goal orientations in the students of the Education Faculty of Alicante. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 1, 575–584. [Google Scholar]

- Hulleman, C.S.; Schrager, S.M.; Bodman, S.M.; Harackiewicz, J.M. A meta-analytic review of achievement goal measures: Different labels for the same constructs or different constructs with similar labels? Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 422–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, S.J.; DiStefano, C. Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modelling. In Structural Equation Modelling. A Second Course; Hancock, G.R., Mueller, R.O., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2006; pp. 269–314. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Le Fevre, C. Implications of manipulating anticipatory attributions on the strategy use of defensive pessimists and strategic optimists. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 1999, 26, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norem, J.K.; Smith, S. Defensive pessimism: Positive past, anxious present, and pessimistic future. In Judgments over Time: The Interplay of Thoughts, Feelings, and Behaviors; Sanna, L.J., Chang, E.C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.J.; Marsh, H.W.; Debus, R.L. Self-handicapping and defensive pessimism: Exploring a model of predictors and outcomes from a self-protection perspective. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norem, J.K.; Illingworth, K.S.S. Strategy dependent effects of reflecting on self and tasks: Some implications of optimism and defensive pessimism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, F.; Martin, A.J.; Ginns, P.; Berbén, A.B.G. Students’ self-worth protection and approaches to learning in higher education: Predictors and consequences. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, J.M. Optimistic and defensive-pessimist students: Differences in their academic motivation and learning strategies. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.-Z.; Chen, C.-Y.; Liang, T.-L. A motivational analysis of defensive pessimist and long-term wellbeing after achievement feedback. Bull. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 41, 733–749. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, C.; Soto-López, T.; Cuesta, M. Needs and demands for psychological care in university students. Psicothema 2019, 31, 414–421. [Google Scholar]

- UN General Assembly. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–35. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html (accessed on 30 August 2020).

- Gustems-Carnicer, J.; Calderón, C. Virtues and character strengths related to approach coping strategies of college students. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2016, 19, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T. Underachieving to Protect Self-Worth. Theory, Research and Interventions; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, S.; Garner, B. Teaching Soft Skills to Business Students. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q 2016, 79, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiano, V.; Schleutker, K.; Petrone, L.; González-Bernal, J. Towards identifying the soft skills needed in curricula: Finnish and Italian students’ self-evaluations indicate differences between groups. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SE | — | ||||

| 2. DP | −0.59 *** | — | |||

| 3. LG | −0.12 *** | 0.28 *** | — | ||

| 4. PApG | −0.46 *** | 0.43 *** | −0.18 *** | — | |

| 5. PAvG | −0.22 *** | 0.11 *** | −0.37 *** | 0.56 *** | — |

| M | 3.41 | 2.35 | 3.24 | 3.30 | 3.24 |

| SD | 0.52 | 0.87 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.87 |

| Asymmetry | −0.39 | 0.83 | −0.45 | −0.51 | −0.60 |

| Kurtosis | −1.41 | −0.49 | −0.65 | −0.71 | 0.05 |

| Model Description | Coef. | SE | t | p | LCI | UCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: LG | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| SE → DP | −0.995 | 0.042 | −23.549 | 0.000 | −1.078 | −0.912 |

| SE → LG | 0.145 | 0.071 | 2.016 | 0.044 | 0.003 | 0.286 |

| DP → LG | 0.368 | 0.042 | 8.620 | 0.000 | 0.284 | 0.452 |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| SE → DP → LG | −0.367 | 0.049 | — | — | −0.463 | −0.263 |

| Total effect | −0.222 | 0.060 | −3.705 | 0.000 | −0.340 | −0.104 |

| Dependent variable: PApG | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| SE → PApG | −.557 | 0.060 | −9.203 | 0.000 | −0.676 | −0.438 |

| DP → PApG | 0.261 | 0.036 | 7.246 | 0.000 | 0.190 | 0.332 |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| SE → DP → PApG | −0.260 | 0.035 | — | — | –0.331 | −0.192 |

| Total effect | −0.818 | 0.050 | −16.345 | 0.000 | −0.916 | −0.719 |

| Dependent variable: PAvG | ||||||

| Direct effect | ||||||

| SE → PAvG | −0.388 | 0.063 | −6.090 | 0.000 | −0.513 | −0.263 |

| DP → PAvG | −0.025 | 0.037 | −0.684 | 0.493 | −0.100 | 0.048 |

| Indirect effect | ||||||

| SE → DP → PAvG | 0.025 | 0.035 | — | — | −0.043 | 0.096 |

| Total effect | −0.362 | 0.051 | −7.057 | 0.000 | −0.462 | −0.261 |

| Model Description | Coef. | SE | t | p | LCI | UCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: LG | ||||||

| SE x DP → LG | −0.457 | 0.083 | −5.493 | 0.000 | −0.621 | −0.294 |

| Conditional effect of SE on LG for different values of the moderator (DP) | ||||||

| DP = 1.545 | 0.490 | 0.094 | 5.174 | 0.000 | 0.304 | 0.675 |

| DP = 2.000 | 0.282 | 0.075 | 3.754 | 0.000 | 0.134 | 0.430 |

| DP = 3.545 | −0.425 | 0.125 | −3.381 | 0.000 | −0.671 | −0.178 |

| Dependent variable: PApG | ||||||

| SE x DP → PApG | −0.287 | 0.070 | −4.066 | 0.000 | −0.426 | −0.148 |

| Conditional effect of SE on PApG for different values of the moderator (DP) | ||||||

| DP = 1.545 | −.340 | 0.080 | −4.240 | 0.000 | −0.498 | −0.183 |

| DP = 2.000 | −0.471 | 0.063 | −7.392 | 0.000 | −0.596 | −0.346 |

| DP = 3.545 | −0.915 | 0.106 | −8.590 | 0.000 | −1.124 | −0.706 |

| Dependent variable: PAvG | ||||||

| SE x DP → PAvG | 0.103 | 0.074 | 1.386 | 0.165 | −0.043 | 0.250 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ferradás, M.d.M.; Freire, C.; Núñez, J.C.; Regueiro, B. The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Achievement Goals in University Students: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Defensive Pessimism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187531

Ferradás MdM, Freire C, Núñez JC, Regueiro B. The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Achievement Goals in University Students: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Defensive Pessimism. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187531

Chicago/Turabian StyleFerradás, María del Mar, Carlos Freire, José Carlos Núñez, and Bibiana Regueiro. 2020. "The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Achievement Goals in University Students: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Defensive Pessimism" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187531

APA StyleFerradás, M. d. M., Freire, C., Núñez, J. C., & Regueiro, B. (2020). The Relationship between Self-Esteem and Achievement Goals in University Students: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Defensive Pessimism. Sustainability, 12(18), 7531. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187531