1. Introduction

The urgency and immensity of challenges like climate change and social inequality call for new ways of understanding the world and effecting change. Such “wicked problems” [

1] are difficult to solve, as they are complex, contested and ambiguous with respect to their underlying values and causes [

2] and display complex interdependencies with prevailing economic, technological and social systems. In confronting these societal challenges, transitions scholars advocate moving beyond incremental improvements, which have proven ineffectual, to find ways of achieving fundamental transitions or transformations in core systems in the direction of sustainability [

3]. Such transitions entail “profound changes in dominant institutions, practices, technologies, policies, lifestyles and thinking” [

4] (p. 6), at the heart of which are novel processes for knowledge production and social learning [

5,

6].

One such process is transdisciplinary (TD) coproduction, a knowledge production process in which individuals with different disciplinary, professional and experiential backgrounds combine academic and practice-based knowledges in the shared production, interpretation and ultimate use of scientific knowledge and its products [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These attributes of TD coproduction suggest optimal conditions for the social learning deemed important for sustainability transitions [

2]. In the context of sustainability transitions, social learning generally refers to collective learning that generates collective responses to a shared dilemma or societal challenge. While such learning is clearly important, more work is needed to conceptualize social learning within TD coproduction and to better understand precisely how learning unfolds and knowledge is produced in such configurations. Indeed, the varied use of the term “social learning” across multiple disciplines and the consequent ambiguity surrounding its causes and effects has resulted in a notable lack of conceptual clarity surrounding the concept. This makes it difficult to assess whether social learning has occurred and, if so, what kind of learning has taken place, to what extent, between whom and how [

13].

To address this challenge, this paper develops an analytical framework that applies a social practice theory (SPT) lens to illuminate the constituent elements and dynamics of social learning in the context of TD coproduction. Adopting an SPT approach affords a means of interpreting concrete practices at the local scale and exploring the potential for scaling them up. This framework is then applied to a real-world case in order to illustrate how social learning unfolded in a grassroots TD coproduction process. The process under study took place over 2018–2019 and brought together researchers from the University of Toronto, two funders (The Atmospheric Fund (TAF) and the City of Toronto) and 11 community practitioners who each represented a different climate intervention located in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA). The aim of this effort was to codevelop an evaluation framework that would enable the assessment of their processes, their short- to medium-term outcomes and any longer or deeper sustainability impacts.

The aim of this paper is to bring coproduction processes for transition into conversation with social learning in order to clarify and yield a deeper understanding of both. Doing so sheds light on social learning’s plural and dynamic nature in the context of TD coproduction efforts, in turn potentially strengthening the TD coproduction effort in the process. Ultimately, this forms the basis for a future research agenda that explores and demonstrates how social learning might be operationalized or leveraged in service of sustainability transitions. This paper is structured as follows: a review of the TD coproduction, social learning and social practice theory literatures, which underpin the social learning analytical framework, leads into a discussion of the analytical framework. This is followed by a description of the TD coproduction case at the centre of this study and how it is illustrative of the processes and outcomes of social learning referenced in the framework. The paper concludes with a discussion of the significance of conceptualizing social learning and TD coproduction in this way, particularly as a foundation for future research.

1.1. Conceptual Framework

1.1.1. TD Coproduction

TD coproduction of knowledge refers to the relocation of research activities out into communities, enabling researchers and societal actors to produce knowledge together by sharing in the joint framing of problems and goals as well as the management and ownership of research processes and related products [

14,

15]. In bringing together actors with diverse backgrounds, experiences and worldviews, TD coproduction can be extremely difficult to undertake in practice but rewarding if new ideas, understandings, trust and commitment emerge. Coproduction processes are particularly useful for addressing sustainability challenges, as they offer an avenue for engaging with sustainability’s “essentially contested” nature [

16,

17], meaning that the specific meaning and interpretation of sustainability is far from universally agreed upon despite widespread acceptance of its importance. Thus, by its very nature, sustainability demands ongoing, place-based conversations informed by the unique beliefs, values, interests and many knowledges of the diverse collectives exploring its meaning and address. Such a view is articulated through the concept of “procedural sustainability”, whereby sustainability is an emergent property of dialogue and negotiation that addresses the inherently normative and ethical question of how we should live and what choices we want to make given the best available scientific knowledge [

18,

19]. Such processes must be designed to make sense of the multiplicity of (potentially messy) perspectives while mediating the inevitable conflicts and engaging deeply with dimensions of power toward ultimately producing new understandings about sustainability issues and their possible solutions. Social learning provides one such mechanism for sense-making through dialogue, reflexivity and experimentation that may help to improve processes while opening up opportunities for collective action.

1.1.2. Social Learning

Social learning emerges when individuals and groups employ dialogue to collectively problem-solve; surface assumptions through reflexivity; and use experimentation, improvisation and adaptation in their initiation of novel approaches [

2,

20,

21]. Such learning is believed to have substantive value, producing new shared knowledge and actions with the potential for adapting and responding to complex challenges [

22,

23]. It also holds normative value with learning, particularly that which is aimed at achieving an environmental or social goal, being an end in and of itself [

24]. In addition to the presumed substantive and normative benefits of social learning, some scholars argue that social learning also provides instrumental value by enhancing trust, governance, social legitimacy, attitudinal and behavioural change, stakeholder empowerment and social networks [

6,

11] (p. 45), and by producing new identities, as well as institutions and individual capacities, that are more socially and ecologically robust [

24].

Yet as Parson and Clark [

25] (p. 429) argue, tremendous ambiguity surrounds the concept:

The term social learning conceals great diversity. That many researchers describe the phenomena they are examining as “social learning” does not necessarily indicate a common theoretical perspective, disciplinary heritage, or even language. Rather, the contributions employ the language, concepts, and research methods of a half-dozen major disciplines; focus on individuals, groups, formal organizations, professional communities, or entire societies; and use divergent definitions of learning, of what it means for learning to be “social,” and of theory.

For instance, scholars like Kilvington, Allen [

26], and Fernandez-Gimenez et al. [

27] conceptualize social learning as a deliberative process, one characterized by dialogue, negotiation and reflexivity between actors within social networks, typically in service of a pro-environmental goal (encapsulating both process and purpose). Others, like Reed et al. [

28], place the emphasis on outcomes, arguing that three distinct criteria must be met for social learning to be obtained: (1) a change in understanding in the individuals involved must be demonstrated (i.e., learning outcomes), (2) this change must go beyond the individual and become situated within wider social units or communities of practice (i.e., network effects) and (3) this occurs through social interactions between actors within a social network (i.e., processes or conditions for social learning).

To further muddy the conceptual waters, the “social” in social learning, which refers to the social context that shapes and is shaped by learning [

29,

30,

31], implies multiple settings for and influences on learning. It includes interpersonal settings though which individuals informally and collaboratively learn from one another as well as the culture in which they live and the groups with which they interact [

31]. This challenges the determination of learning causes and effects.

1.1.3. Social Practice

Grounding social learning in the real-world contexts (e.g., TD coproduction efforts) in which it unfolds is one way of bringing clarity to the concept. While TD coproduction offers a potential, site and mechanism for social learning, such learning is not inevitable solely on the basis of the convening of some actors. Both material and nonmaterial elements play an important role in whether and how social learning may (or may not) transpire, and this is where a social practice lens is helpful for illuminating such components and their interactions. Through this lens, TD coproduction is seen as a practice comprised of enmeshed materials, skills and meanings [

32]. Materials, for instance, objects, infrastructures, tools and the body itself, are tangible elements or entities utilized in the practice [

32]. Skills, which are learned through doing and stored in the body and as mental routines, consist of know-how; competences; and ways of feeling, appreciating and doing as well as inherently shared notions of what is (and is not) good, normal, acceptable and appropriate [

33]. Meanings (and images) are concepts, constructs or ideas that are shared socially and provide social and symbolic significance of participation in the practice at any one moment [

32]. Meanings hinge on and inform norms, values and ideologies [

34]. Collectively, all three practice elements shape one another as well as the contexts in which they are used [

35,

36].

Bathing, cooking and driving are examples of common practices that combine materials, skills and meanings and that have been given much attention in the social practices literature. Through this lens, the social is conceptualized as a dense and mutable fabric of entangled practices that perpetually transform as skills, materials and meanings change. Following this notion, society’s spatial and temporal rhythms are tied to the emergence, diffusion, decline and disappearance of practices [

37]. Conceptualizing TD coproduction efforts in this way, which surfaces their material and cultural dimensions, offers a system of identifying and interpreting social phenomena [

38] that is particularly valuable in determining the manner in which social learning unfolds.

1.2. Analytical Framework

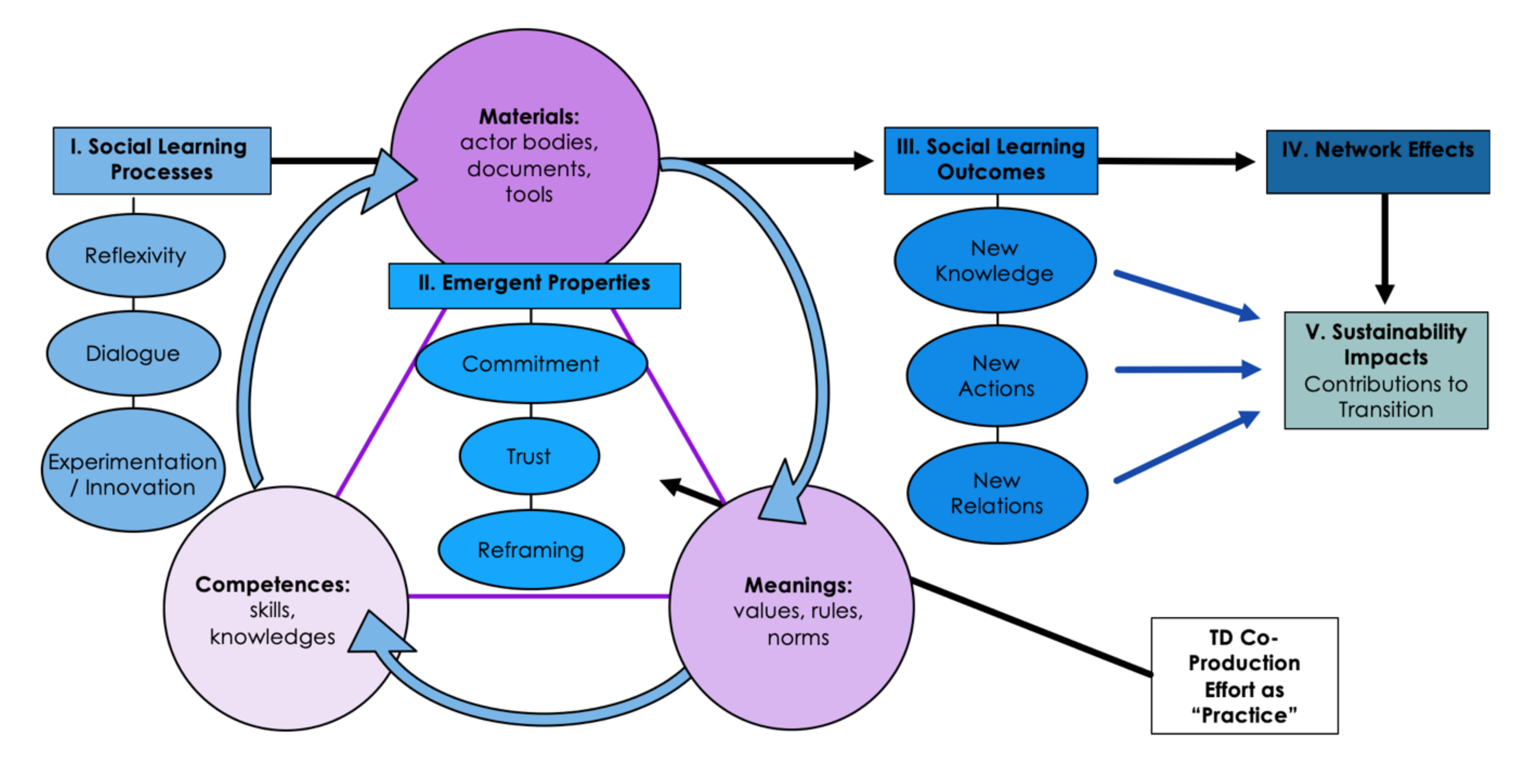

The analytical framework developed here (

Figure 1) offers a coherent conceptualization of social learning in TD coproduction by applying a social practice lens. It is intended to act as a tool for illuminating the entangled dimensions of social learning and coproduction such that they may be enhanced and/or more fully leveraged in service of sustainability-oriented aims. The analytical framework envisions social learning as in a coevolutionary relationship with coproduction, which is theorized as a practice combining materials (e.g., stakeholder bodies, meeting spaces, documents and tools), meanings (e.g., values, norms and rules) and competences (e.g., skills and knowledges) [

32]. These elements are acted upon—shaped and even reconstituted—by the dynamic force of social learning characterized by dialogue, reflexivity and innovation/experimentation. Following Sols, Wal and Wals [

2], this produces emergent properties like trust, commitment and reframing, which in turn give rise to social learning outcomes of new knowledge, new actions and new relations [

2]. Such learning outcomes may then be transferred by networks and taken up in wider social units [

28], representing a potential contribution to sustainability transitions. As discussed in more detail below, this more nuanced and expansive view of social learning attends to its complex and plural nature while also integrating other theoretical resources to contribute to a deeper understanding of coproduction processes that shape and are shaped by it. The analytical framework depicts the elements of social learning acting through the “practice” of coproduction. A few (non-exhaustive) instances of the ways in which they interact and coproduce one another are provided in the ovals in

Figure 1.

From left to right,

Figure 1 shows social learning processes (e.g., reflexivity, dialogue and experimentation/innovation) mutually shaping and being shaped by a TD coproduction effort (comprised of materials, meanings and competences), resulting in emergent properties (e.g., commitment, trust and reframing) that both deepen the coproduction effort as well as lead to social learning outcomes (e.g., new knowledge, new actions and/or new relations). Networks help to spread and increase the uptake of learning outcomes in other social units (e.g., organizations, institutions and societies), ultimately resulting in sustainability impacts.

1.2.1. Social Learning Processes in TD Coproduction

In the realm of sustainability transitions, social learning processes conceive of individual learning and interactive learning simultaneously as taking place “in a process of social change with effects on wider social-ecological systems” [

28] (p. 2). In practice, this entails ongoing interaction, knowledge-sharing, deliberation, dialogue and problem-solving of diverse stakeholders in a trusting environment that is specifically directed at a resource management, governance or sustainability challenge in need of collective action [

39,

40]. Learning is prompted through iterative processes of dialogue, reflexivity and experimenting with solutions. In supplying the diversity of materials (actors and meeting spaces), meanings (beliefs and values) and competences (knowledges and skills), TD coproduction efforts go beyond offering a passive site at which social learning unfolds to actively supplying the essential ingredients for social learning to transpire. How such elements help to produce emergent properties that ultimately give way to social learning outcomes is described below.

1.2.2. Emergent Properties: Trust, Commitment and Reframing

One piece that often goes unaccounted for, and offers a rationale for the analytical framework presented here, is precisely how social learning processes beget social learning outcomes. In this regard, the Sol et al. [

2] conceptualization is useful in that it sees them as being mediated by emergent properties, which they non-exhaustively identify as trust, commitment and reframing. Trust is a firm belief in the reliability, ability, strength or truth of someone or the expectation that others will act in an agreeable way without the need for intervening [

41]. Commitment is evidenced by the degree to which participating actors (individuals and organizations) dedicate resources to achieving the goals of the project. Time, motivation and money are examples of resources. Reframing features the emergence of new, shared problem definitions regarding previously ill-defined issues faced by a relatively heterogeneous group [

2]

Through an SPT stance, these dynamic components emerge from, and further shape, encounters between TD coproduction’s practice dimensions of materials (stakeholders and participants, meeting spaces and tools), meanings (values, beliefs about the issue area and possible solutions) and competences (e.g., knowledges about the issue area, experience and skills for collaboration). In decoupling these properties from individual human agency, the SPT perspective offers a means of tracing their emergence between social units, generating a deeper understanding of how social learning arises and effects change. The outcomes of deepening trust and commitment and ultimately, reframing problems to produce innovative solutions are described below.

1.2.3. Social Learning Outcomes

Following Beers and van Mierlo [

6], social learning outcomes are understood as resulting from the aforementioned learning processes, here described as created through TD coproduction efforts. These coalesce around (i) new knowledge (and knowledge products), (ii) new actions and/or behaviours and (iii) new relationships. Following Kuhn [

42], Bloor [

43], Latour and Woolgar [

44] and Collins [

45], knowledge here is understood as constituted by social practices, that is, socially constructed, and as such, is emergent, pluralistic, negotiated and coproduced through processes in which practice and knowledge are not separated [

46]. New actions refer to collective approaches to shared challenges generated by the TD coproduction effort. Through an SPT lens, this entails changes in practices, which may be constituted as a pathway that unfolds over time across multiple settings and that is always situated within the evolution of broader social practices and institutions [

47]. New relations are seen as new roles and identities between (new) actors within a TD coproduction effort as well as new relations that develop beyond such configurations. Through an SPT lens, relations also encompass the interactions between actions and events and resemble “a kind of chaotic network of habitual and non-habitual connections, always in flux, always reassembling in different ways” [

48] (p. 19).

1.2.4. Network Effects

According to Reed et al. [

28], the final criterion for social learning is that learning outcomes become dispersed via networks within wider social units, ostensibly beyond the original site of learning. As described in the organizational learning and communities of practice literatures, learning can take root in brains, bodies, routines, dialogue and symbols [

49]. These literatures argue that it may be possible for social units to learn, whether they be institutions, organizations or communities of practice, as opposed to large numbers of individuals learning independently [

13,

50]. The aforementioned emergent properties of trust, commitment and reframing play important roles in forming and strengthening networks essential for transferring social learning outcomes to such social units. Over time, the learning that occurs across networks is thought to have the potential to transform complex situations [

9,

51].

1.2.5. Sustainability Impacts

Though discussed in much greater detail elsewhere [

52], sustainability impacts in the context of sustainability interventions or climate actions are conceptualized as early markers of contributions to sustainability transitions. Such contributions include deep thinking or planning that connects the outcomes of the process/intervention to co-benefits in multiple sustainability domains’ (e.g., health, justice, the economy, the environment, etc.) efforts to shift prevailing norms, values, rules or practices in the direction of sustainability and work on scaling the intervention out or deep.

1.3. Application of Analytical Framework

How this analytical framework might usefully reveal social learning’s plural forms and even strengthen TD coproduction efforts is discussed in the context of a real-world case: a Toronto-based TD coproduction effort that took place over 2018–2019. This effort convened researchers from the University of Toronto, representatives of key funders (The Atmospheric Fund (TAF) and City of Toronto) and leaders of neighbourhood-scale interventions drawn from the region’s climate action space, many of which carried out community engagements in their climate actions, campaigns and social change work. Their aim was to codevelop an evaluation framework that assesses the ongoing processes, short- to medium-term outcomes and longer and/or deeper sustainability impacts of small-scale sustainability-oriented interventions. This effort responded to the fact that much assessment of climate action and community engagement interventions looks primarily at process issues (e.g., numbers of participants), and to some extent, at direct and indirect outcomes (e.g., short- to medium-term results such as reports and changes in organizational or individual behaviour as well as new policies and programs), but rarely at sustainability impacts (e.g., deeper, long-term results that contribute to sustainability transitions). By looking at a full suite of results, framework users (e.g., funders like TAF as well as intervention leaders) get a better sense of the individual and collective impact such climate interventions are having as well as the progress being made on implementing TransformTO, the City of Toronto’s climate action plan [

53,

54]. Such a framework also provides a critical tool for project managers, who are asked to perform evaluations of their projects but who typically have few resources and little expertise in doing so.

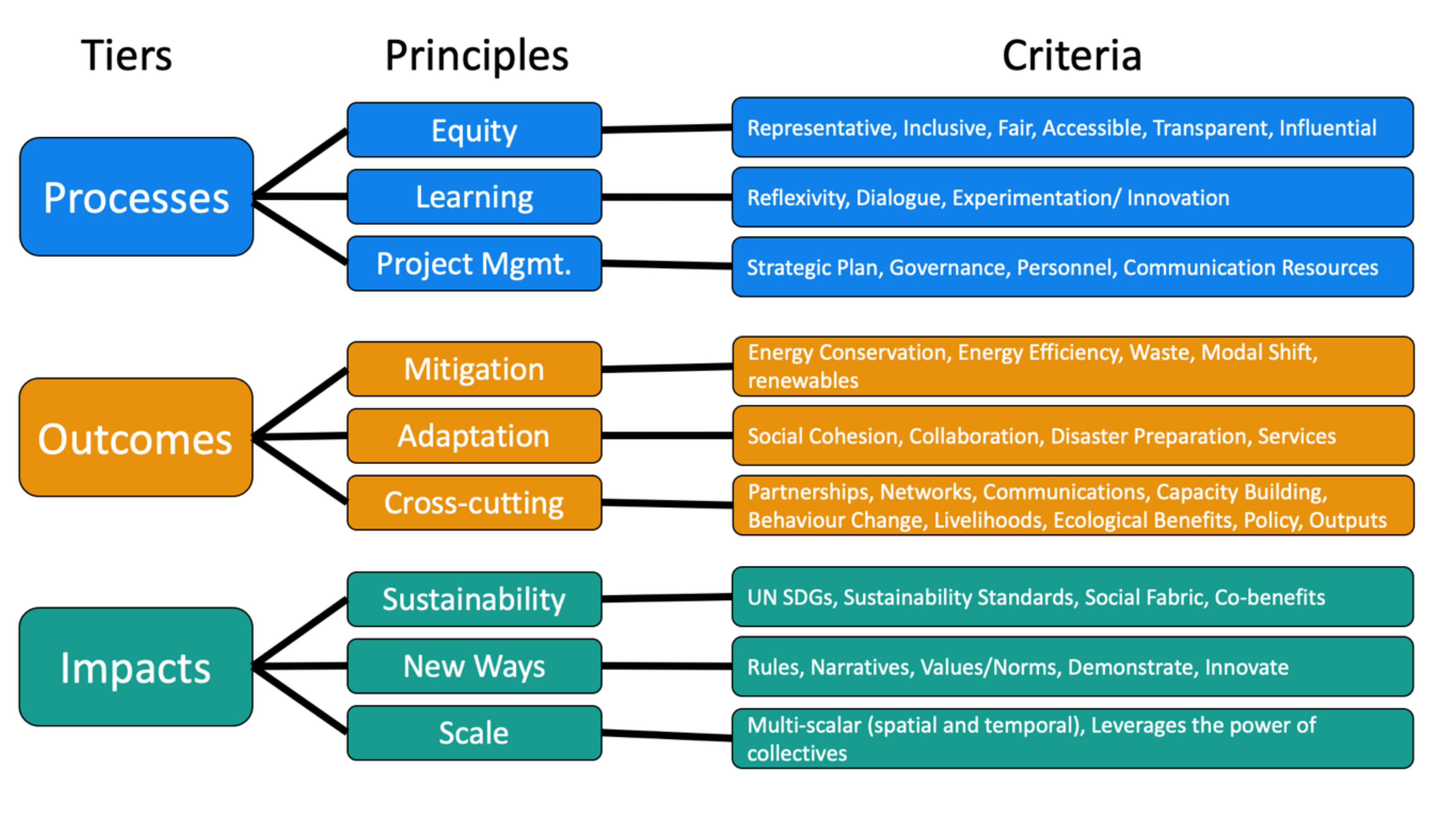

The result of this TD coproduction effort was a multipronged (assessing projects at different stages), light-touch (cost-effective and easy to use), utilization-focused [

55] (the results are valuable to intervention leaders as well as just funders) evaluation framework that enables assessment of a broad suite of results, namely, the processes, outcomes and sustainability impacts, of neighbourhood- or smaller-scale climate change interventions (see

Figure 2). The primary method of evaluation consisted of a self-evaluation questionnaire, which may have been supplemented with a document analysis and/or an interview with an intervention affiliate (someone who was aware of the intervention but was at arm’s length to it). The results of these methods were probing questions, insights and recommendations customized to the evaluation needs of framework users. The framework also functions as a knowledge-sharing platform—a mechanism for generating and sharing lessons learned by projects and facilitating peer-to-peer coaching and learning—in support of a learning community comprised of people working throughout the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area’s climate action and community engagement spaces. Although evaluation was the explicit focus of this group, social learning was deeply embedded in both the process of developing the framework and the framework itself.

From left to right,

Figure 2 displays three evaluative tiers (left column): the first (top row) assesses ongoing intervention processes (including external community engagement processes and internal project management processes), the second (middle row) assesses short- to medium-term outcomes of an intervention and the third (bottom row) assesses contributions to deep or long-term sustainability impacts. For each tier, principles have been identified (middle column)—drawn from the literature and from the input of coproducers—that climate action interventions might strive to realize along with assessment criteria for intervention leaders to self-evaluate the degree to which those principles are deemed important and apparent in their interventions, as evidenced by criteria (right column). Options for adding additional criteria and for stating that a criterion is not relevant are provided in the survey and interview instruments. Respondents’ answers are checked and additional information is gleaned through a document analysis and interview with an arm’s-length project affiliate.

2. Materials and Methods

Upon receipt of approval from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board (Protocol 37210), the following methods were used to codevelop the evaluation framework and also form an illustrative case for applying the analytical framework described in this paper (all materials, data and protocols associated with the publication will be made available to readers upon request to the corresponding author):

- (1)

Review of defining documents (e.g., websites, funding proposals and interim/final reports) for 12 participating interventions (11 small-scale interventions and 1 funding program) whereby criteria in each of the evaluative tiers (processes, outcomes and impacts) helped to evaluate the design and implementation of interventions;

- (2)

In-depth semi-structured interviews (8 interviews conducted in March–May 2019) in which a combination of closed- and open-ended questions was posed to project leaders and their colleagues toward assessing their interventions; and

- (3)

Focus groups (2 Toronto-based workshops: 20 January 2019 and 6 June 2019, with approximately 15 individuals at each) in which facilitated dialogues helped to identify evaluation objectives, develop a corresponding evaluation framework and interpret the evaluation results. An unintended reimagining of the evaluation framework as a platform for a learning community also emerged.

Analysis

The process of data collection and analysis was iterative, meaning all three research instruments were administered, analyzed and refined at multiple stages through collective input from researchers and study participants. Data were coded manually using keywords from the analytical framework.

This case is illustrative in that it offers a basis for testing the analytical framework of social learning and transdisciplinary coproduction independent from the primary aims of the process (developing an evaluation framework). It reveals the entangled and emergent relationship between TD coproduction components (materials, meanings and competences) and social learning processes, which, as a result of their interactions (I), produce emergent properties (EP) and social learning outcomes (SLO).

3. Results

The results of applying the social learning analytical framework are categorized in the following three tables: materials, meanings and competences (See

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). Within each, these codes are used: I—interactions between social learning processes and SPT elements in TD coproduction, EP—emergent property of coproduction and SLO—social learning outcome.

3.1. TD Coproduction Component—Materials

Examples of materials include participant bodies, tools and meeting implements.

3.2. TD Coproduction Component—Meanings

Examples of meanings include language, values and norms.

3.3. TD Coproduction Component—Competences

Examples of competences include skills, knowledges and capacities.

3.4. Interpretation

This analysis illustrates how various forms of social learning (processes and outcomes) unfolded within a TD coproduction effort, as framed by SPT, which is consistent with social learning’s plural nature. Further, it highlights the coevolutionary relationship social learning has with TD coproduction, whereby they continually respond to and are changed by the other. It is too soon to glean network effects or fully realized contributions to sustainability transitions, but there are some early indications of both, which are summarized below.

3.4.1. Network Effects

The main output or knowledge product of this TD coproduction effort was an evaluation framework and supporting guidebook, which is now being utilized by a home retrofit project called BetterHomesTO, led by the City of Toronto. It may be further taken up by TAF and more broadly by other funders and projects in need of evaluation support (it is currently under consideration by several entities). This would represent a network effect whereby the embodied learning in these materials might shift organizations’ practices, including adjustments to funding programs, project design and approaches for monitoring and evaluating to better reflect the assessment criteria. Correspondingly, the evaluation tool was designed to capture users’ feedback on the tool itself and continually iterate and improve through use to embody network preferences.

Additionally, out of this coproduction effort emerged a desire for a learning community comprised of evaluation framework users who share their knowledge and mentor one another in support of their respective climate action and sustainability goals. If this community materializes, it will represent a strong network effect: a learning collective stimulating learning at and transmitting learning across multiple learning sites.

3.4.2. Contributions to Sustainability Transitions

The multipronged, light-touch, utilization-focused evaluation tool embeds the perspectives of participants regarding notions of sustainability transitions. A key part of this perspective entails a social practice orientation that prompts evaluators to look at the ways in which an intervention shifts practices (e.g., norms, values, rules and materials). Scalability (out/across/deep) and systems approaches that connect across sustainability domains and scales were other evaluative areas in the impacts tier. Surprisingly, despite the small scale of the interventions in the cohort who codeveloped the evaluation framework, the interviewees expressed deep interest in this most abstract and long-term level of evaluation, and this was, to some extent, reflected in their plans and actions. Indeed, the desire to form and join a learning community reflected a desire to magnify and deepen sustainability impacts. Following the analytical framework developed here, which calls attention to the need for social learning processes that feature dialogue, reflexivity and innovation as well as coproduction efforts reflecting as broad a diversity of views, knowledges and experience as possible, the effort to form a learning community might be enhanced by embedding these elements.

4. Discussion

This case study illustrates some of the ways that plural forms of social learning (processes and outcomes) can unfold through a TD coproduction effort, produced through interactions with social practice elements like diverse materials, meanings and competences. Such elements supply the raw resources for sense-making, challenging assumptions and producing new collective understandings and are simultaneously changed by the social learning processes of dialogue, reflexivity and experimentation; learning is taken up in human bodies (manifest in new practices), learning shifts meanings and learning foments new skills. Out of the mutual dynamism of this relationship comes the emergent properties of trust, commitment and reframing, which in turn have the potential to produce social learning outcomes like new relations, knowledges or actions, which may be taken up in broader social units via network effects. By creating discursive space for the exploration and deep engagement with contested notions of sustainability, entwined social learning and TD coproduction efforts operate as a powerful means of responding to sustainability challenges and conceiving of new pathways for transition.

Understanding that TD coproduction and social learning are in a tightly bound coevolutionary relationship offers two important insights. The first is that investing in social learning approaches, such as hiring skilled facilitators, allowing sufficient time for dialogue, thoughtfully prompting reflexivity and creating opportunities for experimenting with new ideas and learning by doing, not only supports social learning but also improves the participatory experience for TD coproduction participants. It does so by carving out space for them to feel heard, to more meaningfully relate to one another, to learn and grow and to see their ideas come to life. In the case study discussed here, the continual dialogue between coproduction participants regarding their respective evaluation capacities, needs and preferences fed an ongoing cycle of iteration (experimentation and innovation) in both the content (evaluation principles and criteria) and format (question type, online or in-person) of the evaluation framework. The group provided critical feedback on each framework iteration and prompted researchers to be reflexive, particularly in terms of using language that reflected practitioner, rather than academic, preferences. Over the course of the TD coproduction effort, reflexivity drove an exploration of how the evaluation framework might go beyond measuring a set of evaluation principles and criteria embodying them. For instance, efforts were made to ensure the framework not only measured accessibility in interventions being evaluated but was itself accessible by being cost-free and offered in multiple formats. While learning was occasionally frustrated during this TD coproduction effort, a result of deficiencies in facilitation and an initially inhospitable meeting space, these challenges were, for the most part, overcome by coproduction participants seeing their contributions reflected in the evaluation framework. This helped to grow trust between participants and commitment to the effort, which allowed for the reframing that saw this framework reimagined as a platform for a learning community of co-mentors. In short, social learning approaches deepened the degree of participation in the TD coproduction effort, and that participation in turn deepened the learning processes and outcomes that occurred.

The other key insight that emerges out of this analytical framework is the value, from a social learning perspective, of first of all, diversifying the materials, meanings and competences constituting the TD coproduction effort and secondly, mediating the inevitable conflicts and challenges that arise with such diversity. One method for ensuring efforts are rich with diverse individuals, ideas and values and are supported in engaging deeply with the differences such diversity brings is through the evaluation framework developed in the case described here. This framework offers a set of design considerations for new interventions and guideposts for existing interventions to steer in the direction in service of the greater climate or sustainability aims driving the effort. By embedding social learning approaches like dialogue and reflexivity into the assessment criteria of the evaluation framework and experimenting with innovative approaches for mentorship and sharing of learning across a community of framework users, this approach to evaluation helps to operationalize social learning. Indeed, the potential for a community of practice [

56] to enable its members to share and learn through a series of interactions, “thus reflecting the social nature of human learning” [

57], has generated much enthusiasm for this prospect amongst project participants, researchers and others in the region’s climate action and social innovation space. More work is, however, needed to ensure fruitful germination of this idea and directs future research as discussed below.

In the case study detailed here, the group of coproduction participants held very different perspectives on evaluation and related terminology as well as had varying competences with evaluation (a result of participants’ varying experiences in different sectors or settings, including municipal, nonprofit and academic). This generated some confusion and frustration amongst the group early on. Yet this tension represented a creative challenge rife with learning potential that ultimately spurred efforts to not only clarify language but to design the framework with enough flexibility to accommodate vastly different evaluation needs and competences. The end result is an evaluation tool that takes multiple material forms (as a relational learning network and in-person and online survey) and connects evaluation users with different competences, ideas and values in order to enrich learning, both in the context of their individual interventions and across an entire region’s climate action space.

By embedding the SPT perspective and approaches articulated in the social learning analytical framework into the evaluation framework, both in terms of the criteria used to assess interventions and in the evaluation experience itself, a deeper understanding of social learning and social practice theory—gleaned in part by a learning by doing experience—might be imparted in evaluation users and help their respective interventions. Evaluation of this kind could become part of the design considerations for new small-scale sustainability interventions as well as offer important guideposts for existing interventions, potentially helping them learn and better interpret their practices such that they may eventually scale their efforts or better realize their climate or sustainability aims.

Future research should also carefully consider how this approach to evaluation might be implemented in the absence of researchers and within different funding parameters. The cocreation of the tool was resource-intensive, and its uptake by funders and organizations will require commitment and resources. However, mentorship across a learning community and open-source technologies might help to overcome some of the cost burden to ensure this kind of evaluation is accessible and continually improves.

5. Conclusions

This paper developed an analytical framework for clarifying the notion of social learning, which reveals its plural forms and teases out its coevolutionary relationship with TD coproduction efforts for sustainability transitions. A social practice perspective illuminates the material and nonmaterial dimensions of this relationship. In decoupling these properties from individual human agency, the SPT perspective affords a means of tracing their emergence in different groups and social contexts, generating a deeper understanding of how social learning arises and effects change.

This conceptualization of social learning was explored in the context of a real-world case—a Toronto-based TD coproduction effort that convened leaders of small-scale interventions working in the region’s climate action space as well as key funders of their efforts and researchers. Applying the analytical framework to this process demonstrated that the diverse array of practice elements afforded by the TD coproduction effort helped to both spur and embody social learning while simultaneously being shaped and reconstituted by social learning.

Building on one of the core insights of this analytical framework—the need to operationalize social learning and the potential to do so through a novel evaluation approach—informs a future research agenda investigating how this might best be undertaken in the context of neighbourhood-scale interventions striving to realize bold sustainability aims.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.S. and J.R.; data curation, K.S.; formal analysis, K.S. and J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. and K.S.; investigation, K.S. and J.R.; methodology, J.R. and K.S.; project administration, K.S.; resources, J.R.; software, K.S.; supervision, J.R.; validation, J.R.; visualization, K.S. and J.R.; writing—original draft, K.S.; writing—review and editing, J.R. and K.S. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Atmospheric Fund (TAF), grant number 506108, and the University of Toronto by way of the corresponding author’s PhD funding package.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge funding for this research project from The Atmospheric Fund and the University of Toronto. As a community-engaged research project employing a coproduced evaluation approach, we are grateful to our project partners who generously contributed their time, knowledge and insights to this project. Finally, we wish to thank members of our research group, namely, Grégoire Benzakin and Pani Pajouhesh at the University of Toronto, who were instrumental in developing the framework used in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

In accordance with the principles of coproduction, all evaluation framework users, including the funder, contributed to the design of the study, the creation of the framework and the interpretation of results.

References

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.; Van Der Wal, M.M.; Beers, P.J.; Wals, A. Reframing the future: The role of reflexivity in governance networks in sustainability transitions. Environ. Educ. Res. 2018, 24, 1383–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency (EEA). Perspectives on Transitions to Sustainability. 2018. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/perspectives-on-transitions-to-sustainability/file (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Kemp, R.; Loorbach, D.; Rotmans, J. Transition management as a model for managing processes of co-evolution towards sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2009, 14, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beers, P.J.; Mierlo, B.; Hoes, A.C. Toward an integrative perspective on social learning in system innovation initiatives. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caswell, C.; Shove, E. Introducing interactive social science. Sci. Public Policy 2000, 27, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, W.; Thomas, R.; Robert, K.W.; Parris, T.M.; Leiserowitz, A. What is sustainable development? Goals, indicators, values, and practice. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2005, 47, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiek, A.; Talwar, S.; Robinson, J.; O’Shea, M. Toward a methodological scheme for capturing societal effects of participatory sustainability research. Res. Eval. 2014, 23, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Tansey, J. Co-production, emergent properties and strong interactive social research: The Georgia Basin futures project. Sci. Public Policy 2006, 33, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, S.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Martinez-Conesa, I. Antecedents, moderators, and outcomes of innovation climate and open innovation: An empirical study in SMEs. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 118, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegger, D.; Lamers, M.; Van Zeijl-Rozema, A.; Dieperink, C. Conceptualising joint knowledge production in regional climate change adaptation projects: Success conditions and levers for action. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 18, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.; Marschke, M.; Plummer, R. Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob. Environ. Change 2008, 18, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polk, M. Transdisciplinary co-production: Designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures 2015, 65, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F.; Giger, M.; Harari, N.; Moser, S.; Oberlack, C.; Providoli, I.; Schmid, L.; Tribaldos, T.; Zimmermann, A. Transdisciplinary co-production of knowledge and sustainability transformations: Three generic mechanisms of impact generation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 102, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Squaring the circle? Some thoughts on the idea of sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 48, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, S. Mapping sustainable development as a contested concept. Local Environ. 2007, 12, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.; Cole, R.J. Theoretical underpinnings of regenerative sustainability. Build. Res. Inf. 2015, 43, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggs, D.; Robinson, J. International association for environmental philosophy recalibrating the anthropocene. Environ. Philos. 2016, 13, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.; Beers, P.J.; Wals, A. Social learning in regional innovation networks: Trust, commitment and reframing as emergent properties of interaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.; Rodela, R. Social learning towards sustainability: Problematic, perspectives and promise. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 69, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J. Complexity and Sustainability; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2012; pp. 1–354. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Colding, J.; Berkes, F. Synthesis: Building resilience and adaptive capacity in social-ecological systems. In Navigating Social-Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change; Berkes, F., Colding, J., Folke, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 352–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahl-Wostl, C. The importance of social learning in restoring the multifunctionality of rivers and floodplains. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parson, E.A.; Clark, W.C. Sustainable development as social learning: Theoretical perspectives and practical challenges for the design of a research program. In Barriers and Bridges to the Renewal of Ecosystems and Institutions; Gunderson, L.H., Holling, C.S., Light, S.S., Eds.; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 428–459. [Google Scholar]

- Kilvington, M.J.; Allen, W. Social Learning: A basis for practice in environmental management. Landcare Res. Manaaki Whenua 2010, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernandez-Gimenez, M.E.; Ballard, H.L.; Sturtevant, V.E. Adaptive management and social learning in collaborative and community-based monitoring: A study of five community-based forestry organizations in the western USA. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, r01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977; p. 256. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986; p. 617. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Michael, C., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., Souberman, E., Eds.; Harvard University Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. Nord. J. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2013, 1, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuijer, L. Implications of Social Practice Theory for Sustainable Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 7 February 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.A.; Pantzar, M. Consumers, producers and practices: Understanding the invention and reinvention of Nordic Walking. J. Consum. Cult. 2005, 5, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ingram, H.; Schneider, A.; Deleon, P. Social construction and policy design. In Theories of the Policy Process, 2nd ed.; Sabatier, P., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2007; p. 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strengers, Y.; Moloney, S.; Maller, C.; Horne, R. Beyond behaviour change: Practical applications of social practice theory in behaviour change programmes. In Social Practices, Interventions and Sustainability.; Strengers, Y., Maller, C., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- Caletrío, J. Article Review. The hypothesis of the mobility transition. Mob. Lives Forum 2015, 61, 219–249. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Krasny, M.E. The role of social learning for social-ecological systems in Korean village groves restoration. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cundill, G.; Rodela, R. A review of assertions about the processes and outcomes of social learning in natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeman, T. I Trust U. Managing with Trust; Pearson Education Benelux: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1962; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Bloor, D. Knowledge and Social Imagery; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1976; p. 211. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B.; Woolgar, S. Laboratory Life: The Social Construction of Scientific Facts; Sage Publication, Inc.: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1979; p. 291. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J. Some problems and purposes of narrative analysis in educational research. J. Educ. 1985, 167, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, K.; Kothari, A.R. Knowledge ‘Translation’ as social learning: Negotiating the uptake of research-based knowledge in practice. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; p. 138. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, S.D.; Matuszewski, I.L. Ethics and corporate governance. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2014, 12, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackler, F. Knowledge, knowledge work and organizations: An overview and interpretation. Organ. Stud. 1995, 16, 1021–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning in a changing world and changing in a learning world: Reflexively fumbling towards sustainability. S. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ison, R.; Blackmore, C.; Iaquinto, B.L. Towards systemic and adaptive governance: Exploring the revealing and concealing aspects of contemporary social-learning metaphors. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 87, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Robinson, J.B. Measuring sustainability: An evaluation framework for sustainability transition experiments. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 103, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- City of Toronto. TransformTO: Climate Action for a Healthy Equitable, and Prosperous Toronto. 2016. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/services-payments/water-environment/environmentally-friendly-city-initiatives/transformto/transformto-climate-action-strategy/ (accessed on 8 December 2016).

- City of Toronto. Transform to: Climate Action for a Healthy Equitable, and Prosperous Toronto Community Conversation Guide. 2019. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/974b-TTO-Conversation-Guide-V3.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Patton, M.Q. Utilization-Focused Evaluation, 4th ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; p. 637. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. Communities of Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, A. Community of Practice. Better Evaluation. Available online: https://www.betterevaluation.org/en/evaluation-option/community_of_practice (accessed on 5 May 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).