The Importance of the Participatory Dimension in Urban Resilience Improvement Processes

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Sustainability Concept

1.2. The Place of Participatory Processes

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Analysis from the International Perspective

- They incorporate the use of new economies and values, including identity ones, which in turn define a new method of intervention sustained by its own development [45].

- They use urban activists, entrepreneurs, or both, as catalysts for the social potential [48].

- They involve citizens as the true actors in the city self-organisation process [45].

- They include the active participation of the community in the design process [45].

- They benefit the community involved in several ways, not just by improving physical aspects of the space [44].

2.2. Situation in Spain

- They represent landmark successes, corroborated by the awards received, express academic recognition or express acceptance by citizens.

- They represent landmark cases as pioneers in citizen participation in specific areas of Spain.

- They represent landmark cases in terms of research and academic education as reference models for social service-learning and transfer strategies.

- They represent landmark cases that challenge the role of architects as professionals and trigger debate about their responsibilities and abilities.

- They represent landmark cases that exemplify the different roles that a local administration and a group of citizens or professionals can play as the drivers of a participatory action, whether self-managed or collaboratively managed.

2.3. Case Analysis Methodology

- Analysis of the project technical information, plans, timeline, regulations, academic publications and dissemination in the media, awards and distinctions. This information is decisive in order to carry out an in depth study of the case, and in case it did not exist, the case study would be dismissed in this research work.

- Mapping of actors involved, citizens’ and government groups, public administrations, and technical and professional teams. This is a key tool for understanding the process and it must include, not only the actors involved, but also the relationships among them and the collaboration dynamics developed, if any.

- Interviews with technicians and mediators, as well as with the accessible groups, citizens and administration technicians. Deep understanding of the processes can be clarified by documenting opinions, preferably from different types of stakeholders to have a broad and complete perspective.

- In depth analysis of the development of the process, focusing on timescales and schedules, actions, strategies and tools used. This analysis has been done in great depth, using all the data initially extracted. In the first stage, the analysis is carried out individually, and is later used in a comparative way with other case studies, providing a wider perspective for the drawing of conclusions.

- Extraction of conclusions about the characteristics and circumstances predefined as possible catalysts for the success of these projects. They will respond initially to the circumstances and characteristics observed in the international cases as potentially successful. In a later stage, conclusions will be drawn from the case studies and their circumstances and specific development.

- Identification of interesting tools used. Beyond those referred to by international cases such as the map of actors or the graphic, technological and digital tools for management and communication, another type of interesting tools is found.

- Identification of possible guidelines or management methods used in the process that may provide a reference for future cases. The possible use of specific methodologies with a previously established scientific basis is considered, against the construction of new methods.

2.4. Case Studies

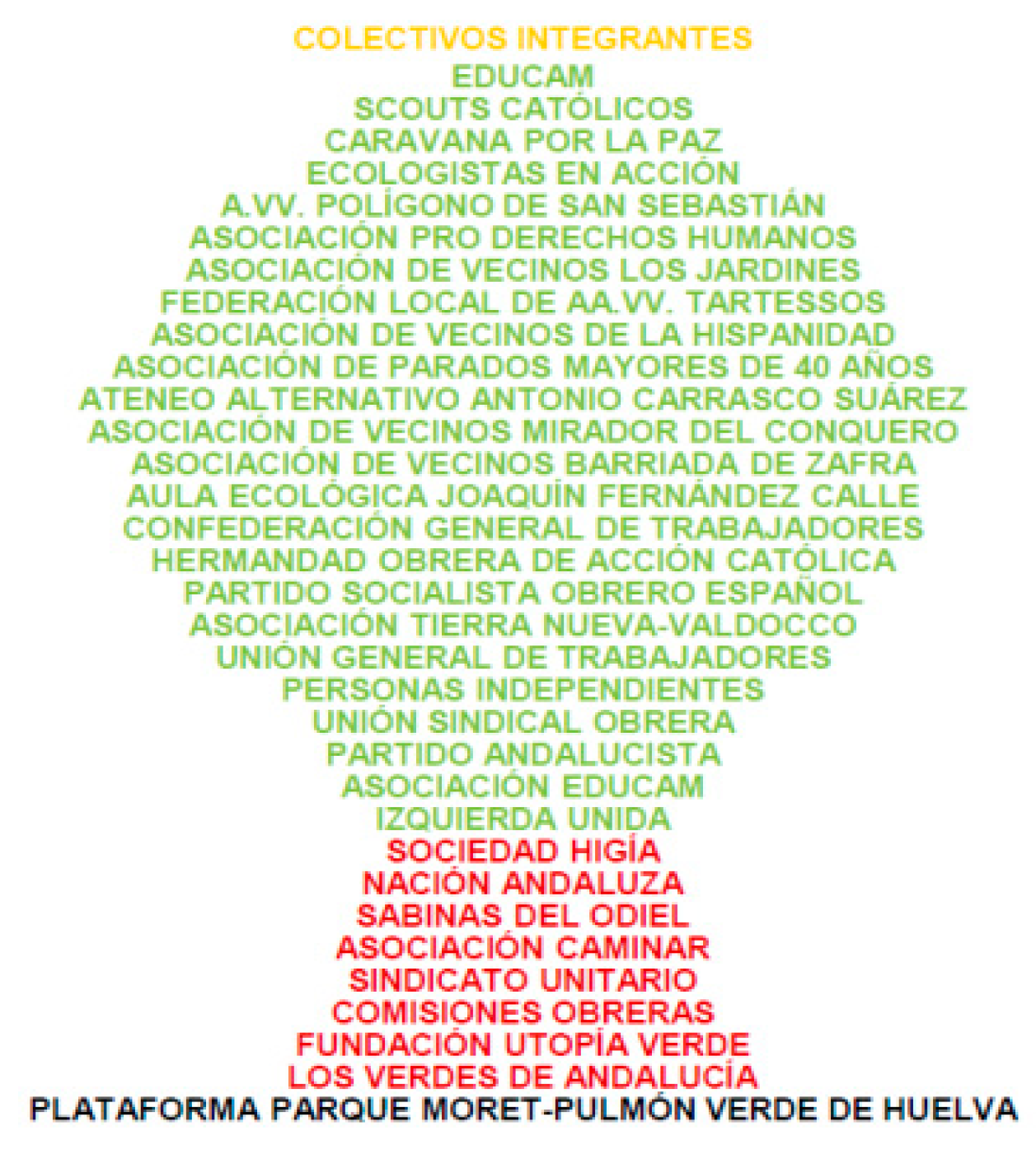

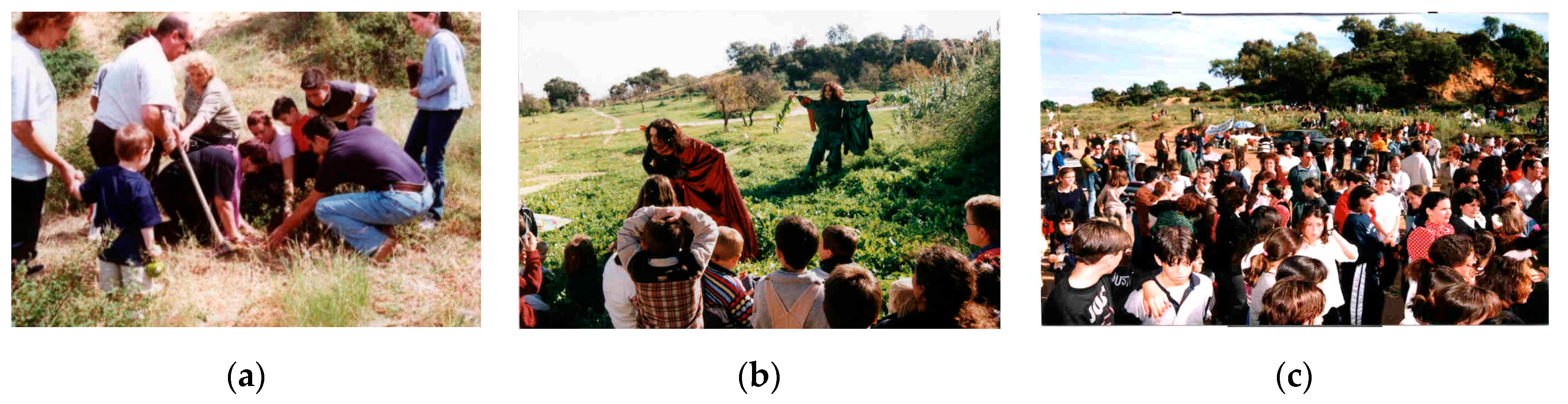

2.4.1. Moret Park, Huelva

- Regular meetings to establish objectives and contents.

- Contact with groups, political parties and organisations to involve them in the meetings.

- Talks, exhibitions, educational, artistic and environmental routes, and a panel of experts to provide a greater understanding of the Moret Park Complex.

- Briefing on the history of the area to contextualise the Moret Park phenomenon.

- Proposals for the design of Moret Park.

2.4.2. Arraijanal Park, Málaga

2.4.3. Pepe Dámaso Cultural Centre, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria

2.4.4. Majanicho Citizen Participation Programme, Fuerteventura

3. Results

4. Discussion

Transferable Opportunities and Learning

5. Conclusions

5.1. Citizen Participation and Environmental Sustainability

5.2. Citizen Participation and Economic Sustainability

5.3. Citizen Participation and Social Sustainability

5.4. The Spanish Case

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Unión Europea. Declaración de Toledo; Unión Europea: Toledo, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Valderrama, L.; Martin-Mariscal, A.; Ureta-Muñoz, C. Rehabilitación urbana integrada: Un proceso complejo pero ineludible. CIC- Centro Informativo de la Construcción 2017, 540, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Squizzato, A. Urban Regeneration: Understanding and Evaluating Bottom-up Projects. Urbanities 2019, 9, 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Estrategia Europa 2020. Una Estrategia Europea para un Crecimiento Inteligente, Sostenible e Integrador; Comisión Europea: Bruselas, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Capolongo, S.; Sdino, L.; Dell’Ovo, M.; Moioli, R.; Della Torre, S. How to assess urban regeneration proposals by considering conflicting values. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdino, L.; Rosasco, P.; Lombardini, G. The Evaluation of Urban Regeneration Processes. In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 47–57. ISBN 9783030332563. [Google Scholar]

- Ló pez de Asiain Alberich, M.; Serra Florensa, R.; Coch Roura, H. Reflections on the Meaning of Environmental Architecture in Teaching. In Proceedings of the 21th Conference on Passive and Low Energy Architecture; de Wit, M.H., Ed.; Technische Universiteit Eindhoven: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 19 September 2004; pp. 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Arcas-Abella, J.; Alcaraz, M.; Bas, A.; Bilbao, A.; Catalan, P.; Cunill, L.; Melo, M.; Huerta, D.; Sauer, B. Impulsa Cíclica [space community ecology] Green Building Council España (GBCe) | Instrumento para la rehabilitación profunda por pasos |; Green Building Council España: Madrid, Spain, 2020; ISBN 9788409183890. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, F.; Arquitecto, A.; Por, T.; Upc, L.; Sevilla, E. La Termografía y la Eficiencia Energética Aplicada a la Construcción Una Salida Laboral en el Ámbito de la Arquitectura Técnica; COAAT: Sevilla, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Martiskainen, M. Hot transformations: Governing rapid and deep household heating transitions in China, Denmark, Finland and the United Kingdom. Energy Policy 2020, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valor, C.; Escudero, C.; Labajo, V.; Cossent, R. Effective design of domestic energy efficiency displays: A proposed architecture based on empirical evidence. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scamman, D.; Solano-Rodríguez, B.; Pye, S.; Chiu, L.F.; Smith, A.Z.P.; Gallo Cassarino, T.; Barrett, M.; Lowe, R. Heat Decarbonisation Modelling Approaches in the UK: An Energy System Architecture Perspective. Energies 2020, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unión Europea. Reglamento (UE) 2018/1999 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 11 de diciembre de 2018 sobre la gobernanza de la Unión, de la Energía y de la Acción por el Clima; Unión Europea: Estrasburgo, France, 2018; Volume 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. Recomendación (UE) 2016/1318 de la Comisión de 29 de julio de 2016 sobre las directrices para promover los edificios de consumo de energía casi nulo y las mejores prácticas para garantizar que antes de que finalice 2020 todos los edificios nuevos sean edi. In Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea; Unión Europea: Bruselas, Belgium, 2016; pp. 46–57. [Google Scholar]

- Cubillos González, R.A.; Trujillo, J.; Cortés Cely, O.A.; Rodríguez Álvarez, C.M.; Villar Lozano, M.R. La habitabilidad como variable de diseño de edificaciones orientadas a la sostenibilidad de Colombia. Rev. Arquit. 2014, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, F. Proyectos del realismo crítico en la era de la simultaneidad: Debates sobre la gestión de la información y las actuaciones en la ciudad construida. Palimpsesto 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triviño Barros, G. The building as a system of management of information. Inf. Construcción 2003, 55, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- D’Alisa, G.; Economía circular. Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary; Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F., Acosta, A., Eds.; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2019; Volume 8, p. 55. ISBN 978-84-9888-884-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wandl, A.; Balz, V.; Qu, L.; Furlan, C.; Arciniegas, G.; Hackauf, U. The circular economy concept in design education: Enhancing understanding and innovation by means of situated learning. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARUP. The Circular Economy in the Built Environment; ARUP: San Francisco, LA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Remøy, H.; Wandl, A.; Ceric, D.; van Timmeren, A. Facilitating circular economy in urban planning. Urban Plan. 2019, 4, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Asiain Alberich, M.L.; Latapié Sére, M. Propuestas para el empoderamiento de los ciudadanos; Participación social ante el cambio climático desde un enfoque arquitectónico y urbano. In Memoria del XXXVI Encuentro de la Red Nacional de Investigación Urbana, AC. Cambio Climático y Expansión Territorial; Valladares Anguiano, R., Chávez González, M.E., Eds.; Programa Editorial de la Red de Investigación Urbana: México D.F., México, 2014; pp. 281–301. ISBN 978-968-6934-33-5. [Google Scholar]

- de Asiain Alberich, M.L. Indicadores de sustentabilidad en urbanismo. In Diálogos Entre Ciudad, Medio Ambiente y Patrimonio; Anguiano, R.V., Ed.; Universidad de Colima: Colima, Mexico, 2014; pp. 100–106. ISBN 978-607-8356-08-9. [Google Scholar]

- Bottero, M.; Bragaglia, F.; Caruso, N.; Datola, G.; Dell’ Anna, F. Experimenting community impact evaluation (CIE) for assessing urban regeneration programmes: The case study of the area 22 @ Barcelona. Cities 2020, 99, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leva, G. Indicadores de Calidad de Vida Urbana.Teoría y Metodología; Politike: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- de Asiain Alberich, M.L.; Valladares Anguiano, R.; Chávez González, M. Habitabilidad y Calidad de Vida como indicadores de la función adaptativa del habitar en el entorno urbano. In Diversas Visiones de la Habitabilidad; Anguiano, R.V., Ed.; Programa Editorial de la Red de Investigación Urbana de México: Puebla, México, 2015; pp. 71–89. ISBN 9789686934366. [Google Scholar]

- López de Asiain Alberich, M. Participatory Approach to Urban Regeneration Processes. In Proceedings of the 3 rd International Congress on Sustainable Construction and Eco-Efficient Solutions; Universidad de Sevilla. Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura: Seville, Spain, 27–29 March 2017; pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez Sainz, M. La ciudad en la economía de la experiencia y el rol de los ciudadanos. Necesidad de participación ciudadana en Bilbao. In Proceedings of the XIII Coloquio Internacional de Geocrítica. El control del espacio y los espacios de control; Universitat de Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 May 2014; Volume 18, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, L.; Lambert, C. Governance, knowledge and sustainability: The implementation of EU directives on air quality in Southampton. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, D.; Boeri, A.; Gianfrate, V.; Palumbo, E.; Boulanger, S.O.M. Resilient cities: Mitigation measures for urban districts. A feasibility study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2018, 13, 734–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Asiain Alberich, M.L.; Cano Ruano, B.; Mendoza, S. Proyecto EUOBs. Mejorando la calidad de vida de los ciudadanos desde la sostenibilidad EUOBs Project. Trying to Improve the Quality of Life of Citizens by Working in terms of Sustainability. WPS Rev. Int. Sustain. Hous. Urban Renew. 2015, 1, 1768–2387. [Google Scholar]

- Gamboa, G.; Munda, G. The problem of windfarm location: A social multi-criteria evaluation framework. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1564–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F.; Ross, H. Community Resilience: Toward an Integrated Approach. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Sánchez, F.S.; Abarca-Álvarez, F.J.; Domingues, Á. Sostenibilidad, planificación y desarrollo urbano. En busca de una integración crítica mediante el estudio de casos recientes. Archit. City Environ. 2018, 12, 39–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J. Models of urban governance: The institutional dimension of urban politics. Urban Aff. Rev. 1999, 34, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás Fornés, M.; Cegarra Dueñas, B. Actores y modelos de gobernanza en las Smart cities. URBS. Rev. Estud. Urbanos Cienc. Soc. 2016, 6, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Margot Breton, M. Neighborhood Resiliency. J. Community Pract. 2001, 9, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez López, M. Dimensiones múltiples de la participación ciudadana en la planificación espacial. Reis 2011, 133, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. La Ciudad y las Masas: Sociología de los Movimientos Sociales Urbanos; Alianza Universidad. Textos 98; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 1986; ISBN 84-206-8098-2. [Google Scholar]

- Borja, J. Ciudadanía y espacio público. Ambiente Desarro. 1998, XIV, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Alguacil Gómez, J. La Calidad de Vida y el Tercer Sector: Nuevas Dimensiones de la Complejidad; Ciudades para un Futuro más Sostenible. Boletín 1997, 3, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M.; Elizalde, A.; Hopenhayn, M. Desarrollo a Escala Humana. Opciones Para el Futuro; Centro de Alternativas al Desarrollo CEPAUR: Santiago, Chile, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, R.; Bai, X.; Smith, M.S.; Costanza, R.; Griggs, D.; Moglia, M.; Neuman, M.; Newman, P.; Newton, P.; Norman, B.; et al. Sustainable urban systems: Co-design and framing for transformation. Ambio 2018, 47, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbiosi, C. Urban regeneration ‘from the bottom up’. City 2017, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, G.; Riva, R.; Architettura, D.; Costruito, A.; Milano, P. Regie e processi innovativi nel progetto di riattivazione sociale e rigenerazione ambientale degli spazi pubblici residuali. TECHNE 2017, 14, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Schmid, J.F.; Schönherr, U.; Weiß, F. Null Euro Urbanismus; Universität Hamburg: Hamburgo, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bialski, P.; Derwanz, H.; Otto, B.; Vollmer, H. ‘Saving’ the city: Collective low—Budget organising and urban practice. Ephemera 2015, 15, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation; Design thinking, design theory; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; ISBN 0-262-32864-X. [Google Scholar]

- Ecosistema Urbano Ecosistema Urbano. Available online: https://ecosistemaurbano.com/es/ (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- La Col LaCol. Available online: http://www.lacol.coop/proj/rehabitar-can-batllo (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Chen, Y. El Campo de la Cebada; YouTube: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- GSA Madrid. Oasis El Ruedo; Vimeo; GSA: Madrid, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [Espacio Elevado al Público]—Plataforma de Acción + Reflexión en Búsqueda de Mejoras en Las Lógicas y Dinámicas Urbanas Que Eleven Al Público Como Protagonista. Available online: https://espacioelevadoalpublico.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Rizoma Fundación. Available online: http://www.rizoma.org/rizoma_fundacion.html (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Paisaje Transversal—Oficina de Planificación Urbana Integral. Available online: https://paisajetransversal.com/ (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- European Commission—Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development—Unit, C. 4 Guidelines, Evaluation of Leader/Clld; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Till, J. Architecture Depends; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780262012539. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A Ladder of Citizen Participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo de Chile. Inventario de Metodologías de Participación Ciudadana en el Desarrollo Urbano; Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2010; ISBN 9789567674145.

- Paisaje Transversal La Regeneración Urbana Integral: El Paso Hacia la Sostenibilidad de Las Ciudades. Available online: https://paisajetransversal.org/2019/08/regeneracion-urbana-integral-participativa-el-paso-sostenibilidad-ciudadades-ruip-barrio/ (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Pretty, J.N. Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Dev. 1995, 23, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussinelli, E.; Tartaglia, A.; Fanzini, D.; Riva, R.; Cerati, D.; Castaldo, G. New Paradigms for the Urban Regeneration Project Between Green Economy and Resilience. In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; p. 380. ISBN 978-3-030-33255-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tsoukias, A.; Montibeller, G.; Lucertini, G.; Belton, V. Policy analytics: An agenda for research and practice. EURO J. Decis. Process. 2013, 1, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silli, F.; Cuidado de Los Comunes: Reglamento de Bolonia. Un Comentario: Prototyping. Available online: http://www.prototyping.es/procomun/cuidado-de-los-comunes-reglamento-de-bolonia-un-comentario (accessed on 31 July 2020).

- Johnson, L. The community planning handbook: How people can shape their cities, towns and villages in any part of the world. Aust. Plan. 2016, 53, 263–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrallo-Jimenez, M.; LopezDeAsiain, M. Confort y sostenibilidad en la arquitectura habitada. Aplicación del conocimiento a la sociedad para la toma de decisiones. In De Forma et vita La Arquitectura en la Relación de lo Vivo Con lo no Vivo; Athenaica: Sevilla, Spain, 2020; ISBN 978-84-17325-94-7. [Google Scholar]

- Dente, B. Understanding Policy Decisions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; ISBN 9783319025193. [Google Scholar]

| Moret Park | Arraijanal Park | Pepe Dámaso Cultural Centre | Majanicho Citizen Participation Programme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New economies and values | Highlights the identity of the neighbouring residential areas linked to the history of the park’s use and its collective memory. This memory is linked to a natural design of the park demanded by the citizens. Attention paid to ecological dynamics. Approach based on flexible use. | Highlights the identity of the natural and archaeological space following the demands of local associations. It rejects economic and speculative performance and it promotes previous interventions from local associations. The land is understood as a common good (right to the town and space justice). Attention paid to ecological dynamics. Inclusive participatory approach, also cross-generation and gender approach. Design approach based on flexibility and reversibility. Extension of time frame. | Highlights the cultural identity of a neighbourhood following proposals emerging from the academic sphere. Experimental emphasis on the concept of citizen participation in Las Palmas. Public funding through traditional means. Chance of highlighting social, cultural, political, commercial and educational activities previously non-existent. Approach based on the flexibility of the built spaces. | Highlights the natural ecosystem and its species. Calls into question urban use, claiming a series of compensatory measures. |

| Financial resources | In this case, the collaboration agreement with the city council provides the necessary resources. | Scarce financial resources coming from the regional government. Boosting of alternative social resources in kind | Governmental financial resources. | Financial resources from the local government are used as a compensation for a wrong legislative procedure. |

| Urban activists and entrepreneurs as catalysts for the social potential | Citizen associations themselves are able to start and manage the process without the need of external activists. | The catalysts in the process are the technicians appointed by the public administration themselves, despite the fact that their proposal is eventually dismissed. | University researchers as initial catalysts of the process. | The group Ben Magwc-Ecologistas en Acción as catalysts of the process thanks to their claims. |

| Role of professionals and technicians. | Technicians act as mediators between the city council and the Moret Park platform of associations, providing answers to the demands through debates and workshops. | Proposal of technicians as mediators, speakers and process managers. | Technicians (in this case researchers) take a mediation role between public administrations and citizens. Technicians are also architecture professionals. The new potential technical role for architects is specifically studied. | Four of the five technical teams involved are professionals coming from different fields linked to environmental science (ornithology, oceanography, etc.). The fifth team carries out a mediation role between public administrations, technicians and citizens. |

| Role of citizens in the process | Citizens are the triggers of the process, although they are involved mainly in the initial stages of it. | Citizens’ proposals as true actors of the process, always working hand-in-hand with public administrations and technicians. Self-pedagogical process. | In this case citizens have a passive role until the building is finished and activities started. The building is used in a variety of ways that go beyond the cultural sphere. Process led by the institutions. | Environmental associations are the ones that initially claim the process. At a later stage, citizens are involved in the process of “fixing the problem”. |

| Community’s participation in the design process | Only in the initial phases. | Participation in all phases of the process, from planning to design and construction. | No involvement in the design process. | There is no involvement in the design process, but it does occur in the later critical process and potential solutions. |

| Innovative use of graphic, technological and digital tools. | Not known. | Use of graphic and technological means of communication between actors, from social networks to purpose-built platforms. | From the starting phase of the research project graphic means are used to inform the public administration of the importance of spaces for participation. | Not known. |

| Provide benefits to the community | All the associations and citizens’ groups are represented, providing specific spatial answers to their needs. | The demands of the social associations are met, involving them in the development of the project. | Technical and academic deficiencies found in the social, political and cultural sphere are taken care of. All sorts of unplanned opportunities arose, providing tangible or intangible benefits to the community. | The right of citizens to decide is acknowledged in the case of a poor management process by the local government. |

| Results of the work | Adequate development of the project and later social acceptance. | Proposal accepted by the administration but turned in a later stage into a traditional management model. | Project developed and finished with the built centre; current management by the local government. | Participatory project developed, pending the implementation of the agreed actions. |

| Parque Moret | Parque Arraijanal | Pepe Dámaso Cultural Centre | Majanicho Citizen Participation Programme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process strategies | Multidisciplinary teams. Citizen-government mediation. Fostering trust between the parts | Multidisciplinary teams, multidisciplinary process. Inclusion of all agents involved throughout the whole process. Adapting time span and strategies to social context. Citizen-government mediation. Information adapted to users, transparency. Community building and fostering trust between the parts. Flexible and adaptable methodology [60]. Time and space for creative innovation | Technical and academic teams in collaboration. Methodology based on the involvement of research project both in the neighbourhood resources desk (promoted by the administration) and in different communal activities. Technicians as drivers of the participatory process and citizen involvement. Short times adapted to traditional local administrative procedures. | Multidisciplinary team with a strong representation of environmental issues. Inclusion of all agents involved during participatory process. Recovery of trust on the part of citizens. Involvement of academic actors that provide credibility and prestige to the process. |

| Tools | Workshops and meetings | Map of actors, workshops, mediation strategies, surveys, interviews, cultural actions. Definition of “motor team” as manager of the participatory process. | Fieldwork is carried out, analysing the neighbourhood’s situation and obtaining a diagnosis of deficiencies in terms of participation. | Map of actors, workshops, mediation strategies, interviews, provision of alternatives. |

| Method participatory phases |

|

|

|

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

LopezDeAsiain, M.; Díaz-García, V. The Importance of the Participatory Dimension in Urban Resilience Improvement Processes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187305

LopezDeAsiain M, Díaz-García V. The Importance of the Participatory Dimension in Urban Resilience Improvement Processes. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187305

Chicago/Turabian StyleLopezDeAsiain, Maria, and Vicente Díaz-García. 2020. "The Importance of the Participatory Dimension in Urban Resilience Improvement Processes" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187305

APA StyleLopezDeAsiain, M., & Díaz-García, V. (2020). The Importance of the Participatory Dimension in Urban Resilience Improvement Processes. Sustainability, 12(18), 7305. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187305