Are Cooperatives an Employment Option? A Job Preference Study of Millennial University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cooperatives as an Employment Option

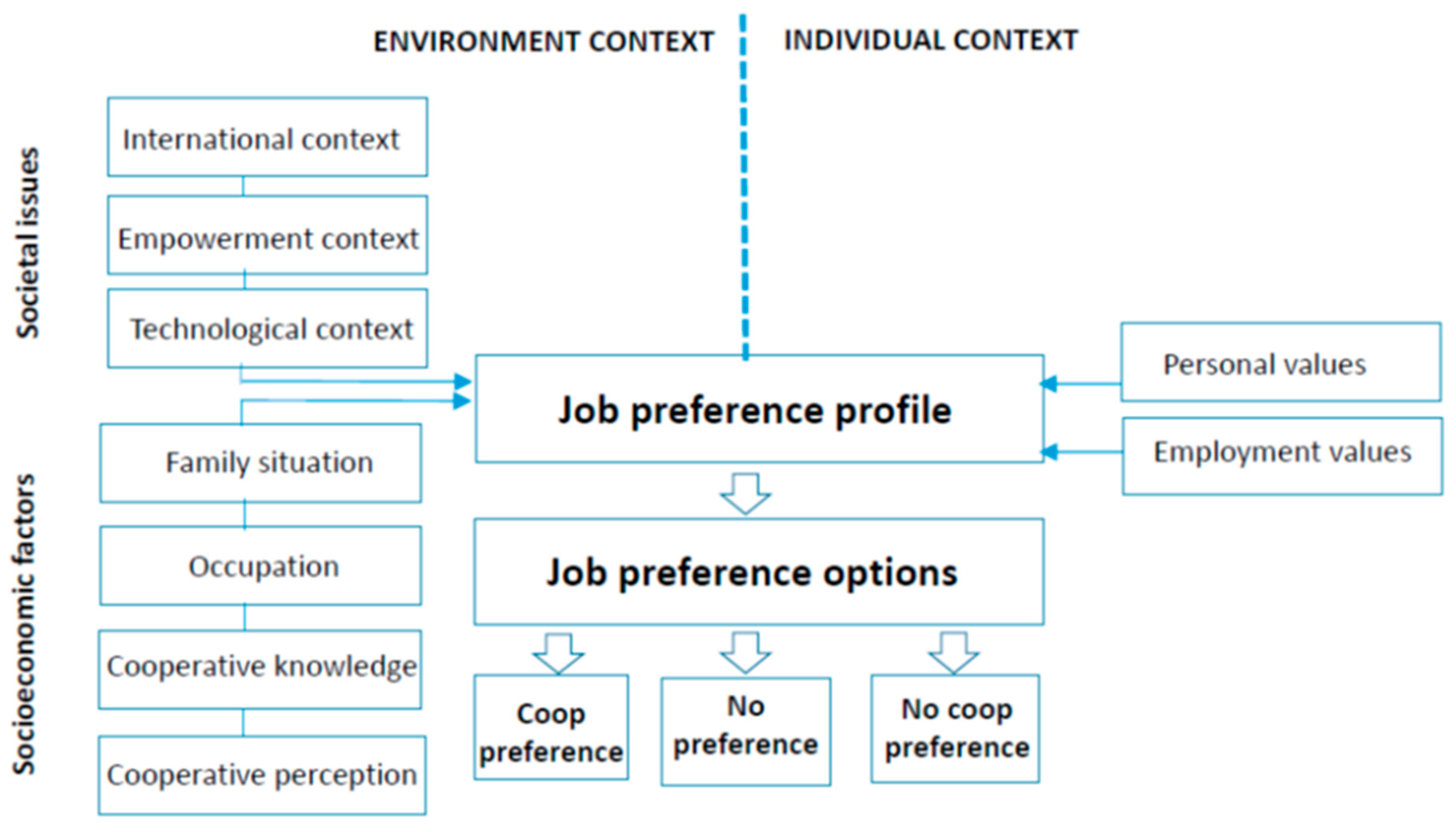

2.2. Theoretical Foundations of Job Preference Creation

2.2.1. Environment Factors Affecting Job Preferences

Societal Issues

Socioeconomic Determinants

2.2.2. Individual Factors Affecting Job Preferences

Personal Values

Employment Values

2.3. Millennials, Job Preferences, and Cooperatives

3. Methodology

3.1. Questionnaire

3.2. Sample

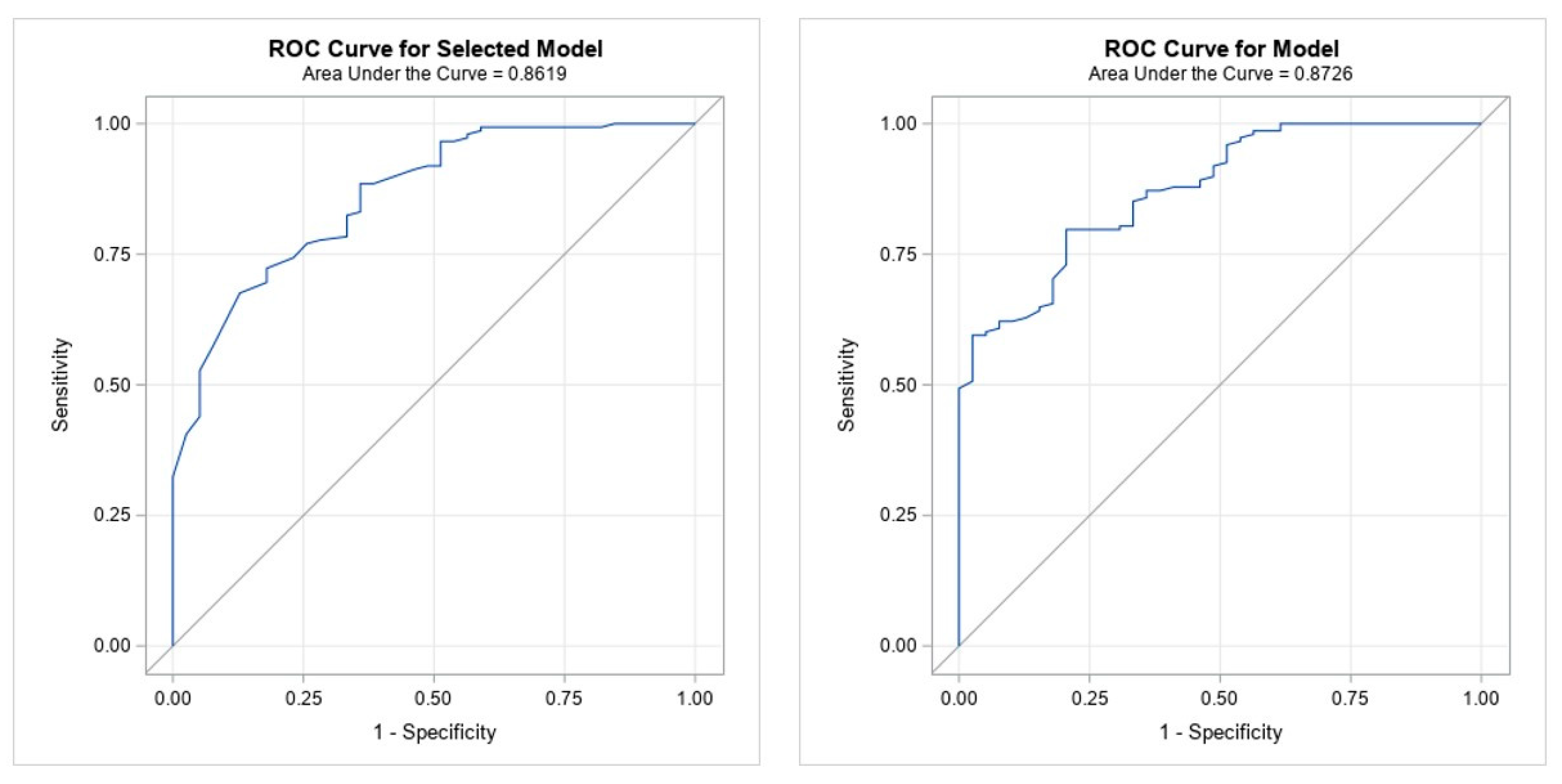

3.3. Model Specification

- JP1i: Students that prefer a cooperative business to work in after finishing their studies.

- JP2i: Students that prefer a non-cooperative business to work in after finishing their studies; and

- JP3i: Students that have no preference between cooperative and non-cooperative businesses.

3.4. Variables

- Personal values (PVai): This includes the most important personal values for students. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “a”. According to the attribute “a” the selected variables are: PV1 honesty/transparency; PV2 altruism (respect for others); PV3 security; PV4 equality/fairness; PV5 individual responsibility; PV6 solidarity; PV7 social responsibility; PV8 democracy; PV9 social success; PV10 personal power; and PV11 other.

- Employment criteria (ECbi): It responds to the criteria that students consider most important in selecting a job. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “b”. According to the attribute “b” the selected variables are: EC1 salary; EC2 impact on society; EC3 career advancement possibilities; EC4 freedom to choose my own working hours/location; EC5 corporate culture; EC6 training and development opportunities; EC7 company social image; EC8 employees’ participation in the company strategic planning; EC9 opportunities to travel internationally; and EC10 other.

- Cooperative perception (CPci): This question captures the perception that the students associate to cooperatives. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “c”. According to the attribute “c” the selected variables are: CP1 honesty/transparency; CP2 altruism (respect for others); CP3 equality/fairness; CP4 security; CP5 individual responsibility; CP6 solidarity; CP7 social responsibility; CP8 democracy; CP9 social success; CV10 personal power; and CP11 other.

- International context (ICdi): It responds to students’ perception of the international problems that impact today’s society. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “d”. According to the attribute “d” the selected variables are: IC1 large scale conflict/war; IC2 climate change/biodiversity preservation; IC3 inequalities (income, discrimination, etc.); IC4 problems of accountability and transparency/corruption; IC5 food and water security; IC6 lack of education; IC7 political instability; IC8 lack of economic opportunity and unemployment; IC9 loss of privacy/security due to technology; IC10 ageing population; and IC11 other.

- Empowerment context (EPCei): This includes the students’ perception of the factors that contribute to the empowerment of individuals. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “e”. According to the attribute “e” the selected variables are: EPC1 start–up ecosystems and entrepreneurship; EPC2 easy access to Internet; EPC3 media independence; EPC4 transparency in governance; EPC5 easy access to opportunities in politics; EPC6 engagement with the local communities; EPC7 financial sufficiency; EPC8 borders opening because of globalization; EPC9 evolution of hierarchical structures; EPC10 free education; and EPC11 other.

- Technological context (TCfi): This question captures the students’ perception of the technologies that have the greatest impact on society. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “f” has selected personal value “f”. According to the attribute “f” the selected variables are: TC1 artificial intelligence; TC2 biotechnology; TC3 robotics; TC4 internet of things; TC5 self–driving cars; TC6 virtual reality (interactive computer-generated reality); TC7 3D printing; TC8 augmented reality (interactive experience of a reality computer-generated); TC9 drones; TC10 domotics (smart home); and TC11 other.

- Socio-economic variables considered in the model are three:

- Family situation (FSgi): This demographic variable describes the students’ family environment. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “g”. According to the attribute “g” the selected variables are: FS1 alone without child(ren); FS2 alone with child(ren); FS3 in a couple without child(ren); and FS4 in a couple with child(ren).

- Occupation (OChi): This includes the main activity of the student. The variable takes the value of 1 if student “i” has selected personal value “h”. According to the attribute “h” the selected variables are: OC1 student; OC2 employee; OC3 entrepreneur; and OC4 other.

- Cooperative knowledge (CKj): This is a binomial variable that registers the value of 1 if the student “i” has cooperative knowledge and 0 if not.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Q1. What is your gender? | |||

| □ | Female | □ | Other |

| □ | Male | □ | Prefer not to answer |

| Q2. What is your family situation? | |||

| □ | Single without children | □ | In a relationship with children |

| □ | Single with children | □ | Other (please specify) |

| □ | In a relationship without children | ||

| Q3. Which of the following best describes your current occupation? | |||

| □ | Student | □ | Employee |

| □ | Entrepreneur | □ | Other (please specify) |

| Q4. According to you, what are the most serious issues affecting the world today? (Please select 3 choices) | |||

| □ | Large scale conflict/war | □ | Political instability |

| □ | Climate change/biodiversity preservation | □ | Lack of economic opportunity and unemployment |

| □ | Inequalities (income, discrimination, etc…) | □ | Loss of privacy/security due to technology |

| □ | Problems of accountability and transparency/corruption | □ | Ageing population |

| □ | Food and water security | □ | Other (please specify) |

| □ | Lack of education | ||

| Q5. According to you, what are the most important factors contributing to people’s empowerment? (Please select 3 choices) | |||

| □ | Start–up ecosystems and entrepreneurship | □ | Financial sufficiency |

| □ | Easy access to Internet | □ | Borders opening because of globalisation |

| □ | Media independence | □ | Evolution of hierarchical structures |

| □ | Transparency in governance | □ | Free education |

| □ | Easy access to opportunities in politics | □ | Other (please specify) |

| □ | Engagement with the local communities | ||

| Q6. According to you, what are the next big technology trends that will transform today society? (Please select 3 choices) | |||

| □ | Artificial intelligence | □ | 3D printing |

| □ | Biotechnology | □ | Augmented reality |

| □ | Robotics | □ | Drones |

| □ | Internet of things | □ | Domotics (smart home) |

| □ | Self–driving cars | □ | Other (please specify) |

| □ | Virtual reality | ||

| Millennials’ values | |||

| Q7. Which of the following values are the most important for you personally? (Please select 3 choices) | |||

| □ | Honesty/transparency | □ | Social responsibility |

| □ | Altruism | □ | Democracy |

| □ | Security | □ | Social success |

| □ | Equality/fairness | □ | Personal power |

| □ | Individual responsibility | □ | Other (please specify) |

| □ | Solidarity | ||

| Q8. According to you, what are your most important criteria when considering job opportunities? (Please select 3 choices) | |||

| □ | Salary | □ | Training and development opportunities |

| □ | Impact on society | □ | Company social image |

| □ | Career advancement possibilities | □ | Employees´ participation in the company strategic planning |

| □ | Freedom to choose my own working hours/location | □ | Opportunities to travel internationally |

| □ | Corporate culture | □ | Other (please specify) |

| Q9. Do you know cooperative business and their characteristics? | |||

| □ | Yes | □ | Non |

| Q10. Which of the following values do you associate most with cooperative principles? (Please select 3 choices) | |||

| □ | Honesty/transparency | □ | Social responsibility |

| □ | Altruism | □ | Democracy |

| □ | Security | □ | Social success |

| □ | Equality/fairness | □ | Personal power |

| □ | Individual responsibility | □ | Other (please specify) |

| □ | Solidarity | ||

| Q11. Based on your own knowledge, values and perception on business organization when choosing between two identical jobs would you rather work for? | |||||

| □ | A cooperative | □ | No preference | □ | A non–cooperative |

References

- Ng, E.S.; Lyons, S.T.; Schweitzer, L. Generational Career Shifts. How Matures, Boomers, Gen. Xers, and Millennials View Work; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cogin, J. Are generational differences in work values fact or fiction? Multi-country evidence and implications. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2268–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, N.; Jepsen, D.M. Career stage and generational differences in psychological contracts. Career Dev. Int. 2009, 14, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, E.; Urwin, P. Generational differences in work values: A review of theory and evidence. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prawitasari, G. The influence of generations on career choice (social cognitive career theory). Konselor 2018, 7, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.T.; Ng, E.S.; Schweitzer, L. Generational career shift: Millennials and the changing nature of careers in Canada. In Managing the New Workforce. International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation; Ng, E.S., Lyons, S.T., Schweitzer, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, N.; Strauss, W. The next 20 years: How customer and workforce attitudes will evolve. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2007, 85, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lahouze-Humbert, E. Le Choc Générationnel: Comment Faire Travailler Ensemble 3 Générations; Éditions Maxima: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meyronin, B. La Génération y, Le Manager Et L’entreprise; Presses Universitaires de Grenoble: Grenoble, France, 2015; pp. 485–487. [Google Scholar]

- Becton, J.B.; Walker, H.J.; Jones-Farmer, A. Generational differences in workplace behavior. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 44, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.S.; Lyons, S.T.; Schweitzer, L. Millennials in Canada: Young workers in a challenging labour market. In The Palgrave Handbook of Age Diversity and Work; Parry, E., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.S.; Oliver, E.G.; Cravens, K.S.; Oishi, S. Managing millennials: Embracing generational differences. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtschlag, C.; Masuda, A.D.; Sebastian, R.B.; Morales, C. Why do millennials stay in their jobs? The roles of protean career orientation, goal progress and organizational career management. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 118, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.B.; Reisel, W.D.; Grigoriou, N.; Fuxman, L.; Mohr, I. The reincarnation of work motivation: Millennials vs older generations. Int. Sociol. 2020, 35, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sao, R.; Tolani, K. What do millennials desire for? A study of expectations from workplace. Helix 2018, 8, 4157–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demel, S.; Mariel, P.; Meyerhoff, J. Job preferences of business and economics students. Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 473–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, O.N.; MacLennan, A.; Dupuis-Blanchard, S. Career preferences of nursing students. Can. J. Aging 2012, 31, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabakus, A.T.; Senturk, A. An analysis of the professional preferences and choices of computer engineering students. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2020, 28, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panlilio, J.; Amurao, E. Work preferences of senior business students of college of business and accountancy. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, R.; Iacovou, C.L. Job selection preferences of business students. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2004, 20, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, L.A.; Muñoz, L.; Johnson, H.W.; Rodriguez, T. Exploring job satisfaction and workplace engagement in millennial nurses. Nurs. Manag. 2020, 28, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baguley, M.M.; Jasman, A.; McIlveen, P.; Rensburg, H.; Ganguly, R. Spoilt for Choice: Factors Influencing Postgraduate Students’ Decision Making; Baguley, M.M., Findlay, Y.S., Kerby, M.C., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Doiron, D.; Hall, J.; Kenny, P.; Street, D.J. Job preferences of students and new graduates in nursing. Appl. Econ. 2014, 46, 924–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xianghan, W. A study on the current job-selection preferences of postgraduate students. Chinese educ. Soc. 1995, 28, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, B.A. Gender and preferences for job attributes: A cross cultural comparison. Sex. Roles 1997, 37, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Carbonell, A.; Ramos, S.G. Preferencia de los y las estudiantes universitarias sobre el empleo desde una perspectiva de género. Rev. Complut. De Educ. 2014, 26, 721–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadlin, N. From major preferences to major choices: Gender and logics of major choice. Sociol. Educ. 2020, 93, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitsohl, H.; Ruhle, S. Millennials´public service motivation and sector choice. A panel study of job entrants in Germany. Public Adm. 2016, 40, 458–489. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, K.; Jun, K.-N. A comparative analysis of job motivation and career preference of Asian undergraduate student. Public Pers. Manag. 2014, 44, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, R. Student preferences for federal, state, and local government careers: National opportunities and local service. J. Public Aff. Educ. 2015, 21, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. Managing the New Workforce. International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation; Ng, E.S., Lyons, S.T., Schweitzer, L., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012; pp. 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, R.P.; Jackson, B.A. Work values preferences of generation Y: Performance relationship insights in the Australian public service. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1997–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzelay, M. The New Public Management. Improving Research and Policy Dialogue; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie, E.; Ashburner, L.; Fitzgerald, L.; Pettigrew, A. The New Public Management in Action; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J.; Doverspike, D.; Miguel, R.F. Public sector motivation as a predictor of attraction to the public sector. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabris, G.T.; Simo, G. Public sector motivation as an independent variable affecting career decisions. Public Pers. Manag. 1995, 24, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.L.; Hondeghem, A. (Eds.) Motivation in Public Management. The Call of Public Service; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, J.L.; Hondeghem, A. Bulding theory and empirical evidence about public service motivation. Int. Public Manag. J. 2008, 11, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzón, J.L. La economía social: Tercer sector en un nuevo escenario. In Economía Social. Entre Economía Capitalista y Economía Pública; CIRIEC-España: Valence, Spain, 1992; pp. 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Quiroz-Niño, C.; Murga-Menoyo, M.A. Social and solidarity economy, sustainable development goals, and communiy development: The mission of adult education & training. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TFSSE. Social and Solidarity Economy and the Challenge of Sustainable Development; Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy (TFSSE): Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Utting, P. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through Social and Solidarity Economy: Incremental Versus Transformative Change; United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, R.; Monzón, J.L. Beyond the crisis: The social economy, prop of a new model of sustainable economic development. Serv. Bus. 2012, 6, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.; Monzón, J.L. Best Pratices in Public Policies Regarding the European Social Economy Post the Economic Crisis; European Economic and Social Committee (EESC): Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bretones, F.D.; Radrigan, M. Actitudes hacia el emprendimiento: El caso de los estudiantes universitarios chilenos y españoles. Ciriec-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2018, 94, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Foncea, M.; Marcuello, C. Entrepreneurs and the context of cooperative organizations: A definition of cooperative entrepreneur. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2013, 30, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, A.; Nobari, N. Antecedents and consequences of cooperative entrepreneurship: A conceptual model and empirical investigation. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 479–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, G.; Sergaki, P.; Baourakis, G. The Cooperative Enterprise. Practical Evidence for a Theory of Cooperative Entrepreneurship; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, K. Youth Unemployment and Under Employment in Canada: More Than a Temporary Problem; Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Adeler, M.C. Enabling policy environments for co-operative development: A comparative experience. Can. Public Policy 2014, 40, S50–S59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulin, P.; Tremblay, B. Desjardins en Mouvement. Comment Une Grande Coopérative De Services Financiers Se Restructure Pour Mieux Servir Ses Membres; Éditions Dorimène/Presses HEC Montréal: Lévis/Montréal, QC, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, S.J.; King, L.A. Work and the good life: How work contributes to meaning in life. Res. Organ. Behav. 2017, 37, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Youth employment: Youth perspectives on the pursuit of decent work in changing times. In World Youth Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- González, A.B.C. Las Preferencias Profesionales y Vocacionales del Alumnado de Secundaria y Formación Profesional Específica. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.L. Vocational preferences. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Dunnete, M., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.L. Making Vocational Choices: A Theory of Vocational Personalities and Work Environments; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Marín, M.; Infante, E.; Troyano, Y. El fracaso académico en la universidad: Aspectos motivacionales e intereses profesionales. Rev. Latinoam. Psicol. 2000, 3, 505–517. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, F.; Ardit, I.; Pla, J. La decisión vocacional ante los estudios universitarios: Una opción de tres alternativas. Rev. Eval. Psicol. 1986, 2, 19–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rocabert, E.; Gimeno, M.J. El proceso de toma de decisión: Un estudio comparativo entre hombre y mujeres. In Nuevas Perspectivas en la Intervención Psicopedagógica: Aspectos Cognitivos, Motivacionales y Contextuales; Beltran, J.A., Domínguez, E., González, E., Bueno, A., Sánchez, A., Eds.; Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 1997; pp. 148–181. [Google Scholar]

- Salamon, L.M.; Newhouse, C.L. The 2020 nonprofit employment report. Nonprofit Econ. Data Bull. 2020, 48, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón, J.L.; Chaves, R. La Economía Social en la Unión Europea; Comité Económico y Social Europeo: Bruselas, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón, J.L.; Chaves, R. Recent Evolutions of the Social Economy in the European Union; European Economic and Social Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Terrasi, E.; Hyungsik, E. Industrial and Service Cooperatives: Global Report 2015–2016; International Organization of Industrial and Service Cooperatives: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Birchall, J. Resilience in a Downturn the Power of Financial Cooperatives; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Carini, C.; Carpita, M. The impact of the economic crisis on Italian cooperatives in the industrial sector. JCOM 2014, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.P.; Torné, I.S. El empleo en las cooperativas en España (2005–2006): El caso de Andalucía. Rev. Cent. Estud. Sociol. Trab. 2018, 10, 115–145. [Google Scholar]

- International Cooperative Alliance. The International Co-Operative Alliance Statement on the Co-Operative Identity; XXXI Congress International Cooperative Alliance: Manchester, UK, September 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, J.; Nyssens, M. El enfoque EMES de empresa social desde una perspectiva comparada. Ciriec-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2012, 75, 7–34. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, C.; Santos, F.J.; Barroso, M.O. Cooperative essence and entrepreneurial quality: A comparative contextual analysis. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2020, 91, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévesque, B. Entrepreneurship collectif et économie sociale: Entreprendre autrement. In Cahier de Recherche; Alliance de Recherche Universités-Communautés en Économie Sociale (ARUC-ÉS): Québec, QC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Monzón, J.L. Empresas sociales y economía social: Perímetro y propuestas metodológicas para la medición de su impacto socioeconómico en la UE. Rev. Econ. Mund. 2013, 35, 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sadi, N.-E.; Moulin, F. Gouvernance cooperative: Un éclairage théorique. Rev. Int. Econ. Soc. 2014, 333, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malo, M.-C.; Tremblay, B. Coopératives financières et solidarités. Financ. Bien Commun 2004, 20, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau, L. Développement des territoires, entreprises collectives et politiques publiques: Le bilan québécois de la dernière décennie. In Cahiers de l’ARUC; Alliance de recherche université-communauté/Innovation sociale et développement des collectivités (ARUC): Québec, QC, Canada, 2009; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Laville, J.-L. La economía social y solidaria frente a las políticas públicas. In Economía Social y Solidaria: Conceptos, Prácticas y Políticas Públicas; Puig, C., Ed.; Universidad del País Vasco: Bilbao, Spain, 2016; pp. 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, S.A. The big five career theories. In International Handbook of Career Guidance; Athanasou, J.A., Van Esbroeck, R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lips-Wiersma, M.; McMorland, J. Finding meaning and purpose in boundaryless careers: A framework for study and practice. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2006, 46, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D.E. Career and life development. In Career Choice and Development; Brown, D., Broods, L., Eds.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1984; pp. 192–234. [Google Scholar]

- Super, D.E. Perspectives in the meaning of value of work. In Designing Careers; Gysbers, L., Ed.; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1985; pp. 184–202. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Occupational choice: A conceptual framework. Ind. Labor Relat. Rev. 1956, 9, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K. The problem of generations. In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge; Kecskemeti, P., Ed.; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1952; pp. 276–322. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, R.V. Person-environment-correspondence theory. In Career Choice and Development; Brown, D., Associates, Eds.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 427–464. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, R.V. The Minnesota theory of work adjustment. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; Brown, D., Lent, R.T., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Dawis, R.V.; Lofquist, L.H. A Psychological Theory of Work Adjustment; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Levenson, A.R. Millennials and the World of Work: An economist’s perspective. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. The 2017 Deloitte Millennial Survey. Apprehensive Millennials: Seeking Stability and Opportunities in an Uncertain World; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. Deloitte Millennial Survey. Millennials Disappointed in Business, Unprepared for Industry 4.0; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. The Deloitte Global Millennial Survey 2019. Societal Discord and Technological Transformation Create a “Generation Disrupted”; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Deloitte. The Deloitte Global Millennial Survey 2020. Resilient Generations Hold the Key to Creating a “Better Normal”; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Unión Europea. Tendencias Mundiales Hasta 2030: ¿Puede la Unión Europea Hacer Frente a Los Retos Que Tiene Por Delante? Oficina de Publicaciones de la Unión Europea: Luxemburgo, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Youth Report. Youth Civic Engagement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Youth Report. Youth and the Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Youth Report. Youth Social Entrepreneurship and the 2030 Agenda; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). Global Shapers Survey; WEF: Cologny, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Au-Yong, O.M.; Gonçalves, R.; Martins, J.; Branco, F. The social impact of technology on millennials and consequences for higher education and leadership. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.A. A phenomenological study of business graduates’ employment experiences in the changing economy. J. Labour Mark. Res. 2018, 52, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Office (ILO). Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Technology and the Future of Jobs; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- PwC. Workforce of the Future. The Competing Forces Shaping 2030; PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, S.; Tacke, T.; Lund, S.; Manyika, J.; Thiel, L. The Future of Work in Europe. Automation, Workforce Transtions, and the Shifting Geography of Employment; McKinsey Global Institut: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Canedo, J.C.; Graen, G.; Grace, M.; Johnson, R.D. Navigating the new workplace: Technology, millennials, and accelerating HR innovation. AIS Trans. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2017, 9, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, N.; Sareen, P.; Potnuru, R.K.G. Employee engagement for millennials: Considering technology as an enabler. Dev. Learn. Organ. 2019, 33, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogamba, I.K. Millennials empowerment: Youth entrepreneurship for sustainable development. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 15, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, D. Transforming culture through personal and career empowerment. Ind. Commer. Train. 2016, 48, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.C.L.; Martínez, G.M.L. Empoderamiento, participación y autoconcepto de persona socialmente comprometida en adolescents chilenos. Interam. J. Psychol. 2007, 41, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, J. Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Prev. Hum. Serv. 1984, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, M. Teoría y Práctica de la Psicología Comunitaria; Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brieger, S.A.; Terjesen, S.A.; Hecavarría, D.M.; Welzel, C. Prosociality in business: A human empowerment framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Empowering Young People to Participate in Society. European Good Practice Projects; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Empowering Youth through National Policies; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). UNDP Youth Strategy 2014–2017. Empowered Youth, Sustainable Future; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- PwC. Engaging and Empowering Millennials; PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abri, N.; Kooli, C. Factors affecting the career path choice of graduates: A case of Oman. Int. J. Youth Eco 2018, 2, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, J.; Holmes, K.; Smith, M.; Southgate, E.; Albright, J. Socioeconomic status and the career aspirations of Australian school students: Testing enduring assumptions. Aust. Educ. Res. 2015, 42, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, R.T.; Pujar, L. Influence of socioeconomic status on career decision making of undergraduate emerging adults. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 7, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Riverin-Simard, D. Career paths and socio-economic status. Can. J. Couns. 1992, 26, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sortheix, F.M.; Chow, A.; Salemla-Aro, K. Work values and the transition to work life: A longitudinal study. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wust, K.; Leko-Simic, M. Students’ career preferences: Intercultural study of Croatian and German students. Econ. Sociol. 2017, 10, 136–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigal, E.A.; Konrad, A.M. The relationship of job attributes preferences to employment, hours of paid work, and family responsibilities: An analysis comparing women and men. Sex. Roles 2006, 54, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, I.; Lindh, A. Job preferences in comparative perspective 1989–2015: A multidimensional evaluation of individual and contextual influences. Int. J. Sociol. 2018, 48, 142–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, A.M. Family demands and job attribute preferences: A 4-year longitudinal study of women and men. Sex. Roles 2003, 49, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuron, L.K.J.; Lyons, S.T.; Schweitzer, L.; Ng, E.S.W. Millennials’ work values: Differences across the school to work transition. Pers. Rev. 2015, 44, 991–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt, N.M.; Rochlen, A.B. Addressing the college-to-work transition: Implications for university career counselors. J. Career Dev. 2008, 35, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérotin, V. Entry, exit, and the business cycle: Are cooperatives different? J. Comp. Econ. 2006, 34, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, R.M.; Torres, S.T.; Farré, P.M. Demografía de las cooperativas en tiempos de crisis. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2018, 93, 51–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buendía-Martínez, I.; Álvarez-Herranz, A.; Moreira, M.M. Business cycle, SSE policy, and cooperatives: The case of ecuador. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambre des Communes. Situation Des Coopératives Au Canada; Parlement du Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kluckhohn, C. Values and value orientations in the theory of action. In Toward a General Theory of Action; Parsons, T., Shils, E.A., Eds.; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 1951; pp. 388–433. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J. Discovering the millennials’ personal values orientation: A comparison to two managerial populations. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.; Gartner, W.B. Properties of emerging organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, J.A. Modeling entrepreneurial career progressions: Concepts and considerations. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1994, 19, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Choi, Y. Generational differences in work values: A study of hospitality management. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 20, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.T.; Duxbury, L.E.; Higgings, C.A. A comparison of the values and commitment of private sector, public sector, and parapublic sector employees. Public Adm. Rev. 2006, 66, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokeach, M. The Nature of Human Values; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value priorities and behavior: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. In The Ontario Symposium: The Psychology of Values; Seligman, C., Olson, J.M., Zanna, M.P., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1996; Volume 8, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Arieli, S.; Sagiv, L.; Roccas, S. Values at work: The impact of personal values in organisations. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 69, 230–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizur, D.; Sagie, A. Facets of personal values: A structural analysis of life and work values. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagie, A.; Elizur, D. The structure of personal values: A conical representation of multiple life areas. J. Organ. Behav. 1996, 17, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, J.M.; Jones, G.R. Experiencing work: Values, attitudes, and moods. Hum. Relat. 1997, 50, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, R.A.; Ester, P. Values and work: Empirical findings and theoretical perspective. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, S.T.; Higgins, C.A.; Duxbury, L.E. Work values: Development of a new three-dimensional structure based on confirmatory smallest space analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 969–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, P.E.; Becker, B.W. Values and the organization: Suggestion for research. Acad. Manag. J. 1975, 18, 550–561. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A. Word related beliefs and human values. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1987, 8, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bretz, R.D. Effects of work values on job choice decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1992, 77, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, C.M.; Sortheix, F.M.; Obschonka, M.; Salmela-Aro, K. What drives future business leaders? How work values and gender shape young adults’ entrepreneurial and leadership aspirations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 107, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, A.F.; Triady, M.S.; Suci, R.P.N. Working values preferences among gen-x, y and baby boomers in Indonesia. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2018, 26, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, S.T. An Exploration of Generational Values in Life and at Work; Eric Sprott School of Business: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Rounds, J. Stability and change in work values: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 326–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, H.J.; Galambos, N.L. Work values and beliefs of “Generation X2” and “Generation Y”. J. Youth Stud. 2013, 17, 92–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros, M.; Schwartz, S.H.; Surkiss, S. Basic individual values, work values, and the meaning of work. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 1999, 48, 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M. A review of empirical evidence on generational differences on work attitudes. J. Bus. Psychol. 2010, 25, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Freeman, E.C. Generational differences in young adults’ life goals, concern for others, and civic orientation 1966–2009. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environics Institute. Canadian Millennials Social Values Study; The Environics Institute: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Allain, C. Génération y: Qui Sont-Ils, Comment Les Aborder? Un Regard Sur Le Choc Des Générations; Les Éditions Logiques: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lapoint, P.; Liprie-Spence, A. Employee engagement: Generational differences in the workplace. J. Organ. Psychol. 2017, 17, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Okros, A. Harnessing the Potential of Digital Post-Millennials in the Future Workplace, Management for Professionals; Springer: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M. Fire & ice: The United States, Canada and the Myth of Converging Values; Penguin: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, J.; Loewenstein, J.; Lewellyn, P.; Elm, D.R.; Hill, V.; Mcmanus, W.J. Toward discovering a national identity for millennials: Examining their personal value orientations for regional, institutional, and demographic similarities or variations. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2019, 124, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macky, K.; Gardner, D.; Forsyth, S. Generational differences at work: Introduction and overview. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, R.K.; Wright, B.E. The effects of public service motivation on job choice decisions: Disentangling the contributions of person-organization fit and person-job fit. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2011, 21, 723–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.M.; Porto, J.B. Do work values predict preference for organizational values? Psico-USF 2016, 21, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Winter, U.; Thaler, J. Does motivation matter for employer choices? A discrete-choice analysis of medical students’ decisions among public, non-profit, and for-profit hospitals. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 762–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Beyond efficiency or justice: The structure and measurement of public servant’ public values preferences. Adm. Soc. 2020, 52, 499–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Ghatak, M. Profit with Purpose? A theory of Social Enterprise. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2017, 9, 19–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelants, B.; Hyungsik, E.; Terrasi, E. Cooperatives and Employment: A Global Report; CICOPA and Desjardins Group: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ruel, E.; Wagner, W.E.; Gillespie, B.J. (Eds.) The Practice of Survey Research: Theory and Applications; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Willimark, D.K.; Lyberg, L.; Martin, J.; Japec, L.; Whitridge, P. Evolution and adaptation of questionnaire development, evaluation, and testing methods for establishment surveys. In Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires; Presser, S., Rothgeb, J.M., Couper, M.P., Lessler, J.T., Martin, E., Martin, J., Singer, E., Eds.; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Czaja, R.; Blair, J. Designing Surveys. A Guide to Decisions and Procedures, 2nd ed.; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, H.; Hak, T. The productivity of the Three-Step Test-Interview (TSTI) compared to an expert review of a self-administered questionnaire on alcohol consumption. J. Off. Stat. 2005, 21, 103–120. [Google Scholar]

- Helsper, E.J.; Eynon, R. Digital natives: Where is the evidence? Br. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 36, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershatter, A.; Epstein, M. Millennials and the World of Work: An organization and management perspective. J. Bus. Psychol 2010, 25, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrycki, K.; Roy, D.; Venema, H.D.; Brooks, D. Water Security in Canada: Responsibilities of the Federal Government; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coque, M.J. Puntos fuertes y débiles de las cooperativas desde un concepto Amplio de gobierno empresarial. Revesco. Rev. Estud. Coop. 2008, 95, 65–93. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, A.C. Ineficiencia del Mercado y Eficacia de Las Cooperativas; CIRIEC-España: Valencia, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, J. The nature of values and principles. Transaction cost theoretical explanations. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 1996, 67, 633–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coraggio, J.L. Economía Social, Acción Pública y Política (Hay Vida Después Del Neoliberalismo); Ediciones CICCUS: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coraggio, J.L. La economía social y solidaria (ESS): Niveles y alcances de acción de sus actores. El papel de las universidades. In Economía Social y Solidaria: Conceptos, Prácticas y Políticas Pública; Universidad del País Vasco: Bilbao, Spain, 2016; pp. 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Guadaño, J.; Lopez-Millan, M.; Sarria-Pedroza, J. Cooperative entrepreneurship model for sustainable development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeandeau, Q.; Ouchene, N.; Brat, E.; Buendía-Martínez, I. Innovation. the Co-operative Enterprise by and for Millennials; HEC Montréal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leger. Les Milléniaux Québécois et Les Values Cooperatives; Conseil québécois de la coopération et de la mutualité: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arteau, M.; Brassard, M.J. Coopérative et développement territorial: Quels liens? In Cahiers de l’ARUC; Alliance de recherche université-communauté/Innovation sociale et développement des collectivités (ARUC): Québec, QC, Canada, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Buendía-Martínez, I.; Côté, A. Desarrollo territorial rural y cooperativas: Un análisis desde las políticas públicas. Cuad. Des. Rural. 2014, 11, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M. Can cooperatives brand? Exploring the interplay between cooperative structure and sustained brand marketing success. Food Policy 2007, 32, 480–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grashuis, N.J. Branding by U.S. farmer cooperatives: An empircal study of trademark ownership. J. Coop. Organ. Manag. 2017, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot-Soulet, C.; Soluez, S. Être un employeur bancaire coopératif, ça change quoi? De l’influence du modèele coopératif sur la marque employeur. Rev. Française Gestión 2019, 282, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R. Social economy and public policies. Elements for Analysis. In The Emergence of the Social Economy in Public Policy. An International Analysis; Chaves, R., Demoustier, D., Eds.; P.I.E. Perter Lang: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, A.I.; Pérez, M.C.; Rua, C.S. Intereses y perspectivas formativas en economía social y solidaria de los estudiantes universitarios. Ciriec-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2018, 94, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliá, J.F.; Meliá, E.; Miranda, E. Rol de la Economía social y la Universidad en orden a un emprendimiento basado en el conocimiento tecnológico y los valores. Ciriec-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2020, 98, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, M.L.C.; Estrada, V.L.I.; Pabón, F.M.; Tójar, H.J.C. Evaluar y promover las competencias para el emprendimiento social en las asignaturas universitarias. REVESCO Rev. Estud. Coop. 2019, 131, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Job Preference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperative | 45% | Student | 55% | Alone without child(ren) | 44% |

| No preference | 43% | Employee | 34% | In a couple with child(ren) | 20% |

| Non-cooperative | 12% | Entrepreneur | 2% | In a couple without child(ren) | 28% |

| NA | 6% | Other | 2% | ||

| Other | 2% | NA | 6% | ||

| Total | 100% | Total | 100% | Total | 100% |

| Cooperative Knowledge | Students % | Sex | Students % | Language | Students % |

| Cooperative Knowledge | 57% | Female | 55% | English | 6% |

| Non-cooperative knowledge | 43% | Male | 38% | French | 94% |

| NA | 6% | ||||

| Total | 100% | Total | 100% | Total | 100% |

| Personal Values | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributes | Descriptive | # Students | Survey % | Attributes | Descriptive | # Students | Survey % |

| PV1 | Honesty/transparency | 256 | 78% | EC1 | Salary | 188 | 57% |

| PV2 | Altruism (respect for others) | 169 | 52% | EC2 | Impact on society | 127 | 39% |

| PV3 | Security | 170 | 52% | EC3 | Career advancement possibilities | 195 | 59% |

| PV4 | Equality/fairness | 50 | 15% | EC4 | Freedom to choose my own working hours/location | 109 | 33% |

| PV5 | Individual responsibility | 57 | 17% | EC5 | Corporate culture | 160 | 49% |

| PV6 | Solidarity | 68 | 21% | EC6 | Training and development opportunities | 76 | 23% |

| PV7 | Social responsibility | 116 | 35% | EC7 | Company social image | 24 | 7% |

| PV8 | Democracy | 48 | 15% | EC8 | Employees´ participation in the company strategic planning | 55 | 17% |

| PV9 | Social success | 27 | 8% | EC9 | Opportunities to travel internationally | 45 | 14% |

| PV10 | Personal power | 18 | 5% | EC10 | Other | 5 | 2% |

| PV11 | Other | 5 | 2% | ||||

| Technological Context | International Context | ||||||

| Attributes | Descriptive | #Students | Survey % | Attributes | Descriptive | # Students | Survey % |

| TC1 | Artificial intelligence | 296 | 90% | IC1 | Large scale conflict/war | 267 | 81% |

| TC2 | Biotechnology | 176 | 54% | IC2 | Climate change/biodiversity preservation | 78 | 24% |

| TC3 | Robotics | 107 | 33% | IC3 | Inequalities (income, discrimination, etc.) | 176 | 54% |

| TC4 | Internet of things | 52 | 16% | IC4 | Problems of accountability and transparency/corruption | 91 | 28% |

| TC5 | Self-driving cars | 74 | 23% | IC5 | Food and water security | 37 | 11% |

| TC6 | Virtual reality (interactive computer-generated reality) | 55 | 17% | IC6 | Lack of education | 110 | 34% |

| TC7 | 3D printing | 73 | 22% | IC7 | Political instability | 48 | 15% |

| TC8 | Augmented reality | 45 | 14% | IC8 | Lack of economic opportunity and unemployment | 32 | 10% |

| TC9 | Drones | 42 | 13% | IC9 | Loss of privacy/security due to technology | 59 | 18% |

| TC10 | Domotics (smart home) | 58 | 18% | IC10 | Ageing population | 67 | 20% |

| TC11 | Other | 6 | 2% | IC11 | Other | 19 | 6% |

| EMPOWERMENT CONTEXT | COOPERATIVE PERCEPTION | ||||||

| Attributes | Descriptive | # Students | Survey % | Attributes | Descriptive | # Students | Survey % |

| EPC1 | Start-up ecosystems and entrepreneurship | 141 | 43% | CP1 | Honesty/transparency | 56 | 17% |

| EPC2 | Easy access to Internet | 113 | 34% | CP2 | Altruism (respect for others) | 38 | 12% |

| EPC3 | Media independence | 35 | 11% | CP3 | Equality/fairness | 109 | 33% |

| EPC4 | Transparency in governance | 99 | 30% | CP4 | Security | 11 | 3% |

| EPC5 | Easy access to opportunities in politics | 13 | 4% | CP5 | Individual responsibility | 7 | 2% |

| EPC6 | Engagement with the local communities | 114 | 35% | CP6 | Solidarity | 118 | 36% |

| EPC7 | Financial sufficiency | 137 | 42% | CP7 | Social responsibility | 115 | 35% |

| EPC8 | Borders opening because of globalization | 70 | 21% | CP8 | Democracy | 85 | 26% |

| EPC9 | Evolution of hierarchical structures | 71 | 22% | CP9 | Social success | 14 | 4% |

| EPC10 | Free education | 181 | 55% | CP10 | Personal power | 4 | 1% |

| EPC11 | Other | 10 | 3% | CP11 | Other | 4 | 1% |

| Model Information. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Set | Analyse Baseprepare | Ordered Value | JP | Total Frequency |

| Response Variable | EP | 1 | 1 | 148 |

| Number of Response Levels | 3 | 2 | 2 | 39 |

| Model | Generalized logit | 3 | 3 | 141 |

| Optimization Technique | Newton–Raphson | Logits modeled use EP = 2 as the reference category | ||

| Observations Read | 328 | |||

| Observations Used | 328 | |||

| Effect | DF | Wald Chi–Square | Pr > ChiSq |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC2: Climate change | 2 | 5.5105 | |

| IC5: Food and water security | 2 | 11.0733 | |

| IC6: Lack of education | 2 | 10.2400 | |

| EPC5: Easy access to politics | 2 | 9.3216 | |

| EPC6: Engagement with the local communities | 2 | 8.5028 | |

| EPC9: Evolution of hierarchical structures | 2 | 9.0092 | |

| EC1: Salary | 2 | 7.9586 | |

| PV3: Security | 2 | 4.9258 | |

| PV5: Individual responsibility | 2 | 10.4155 | |

| PV9: Social success | 2 | 10.0893 | |

| PV10: Personal power | 2 | 12.3545 | |

| CK: Cooperative knowledge | 2 | 33.2057 |

| Analysis of Maximum Likelihood Estimates | Odds Ratio Estimates | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | EP | DF | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Chi–Square | Pr > ChiSq | Point Estimate | 95% Wald Confidence Limits | ||

| Intercept | 1 | 1 | 1.5261 | 0.8020 | 3.6207 | 0.0571 | – | – | – | |

| Intercept | 3 | 1 | 2.3295 | 0.7373 | 9.9818 | 0.0016 | – | – | – | |

| IC2: Climate change | 1 | 1 | 1.3844 | 0.6934 | 3.9861 | 0.0459 | 3.992 | 1.026 | 15.541 | |

| IC2: Climate change | 3 | 1 | 1.5609 | 0.6658 | 5.4965 | 0.0191 | 4.763 | 1.292 | 17.563 | |

| IC5: Food and water security | 1 | 1 | −2.0641 | 0.6456 | 10.2214 | 0.0014 | 0.127 | 0.036 | 0.450 | |

| IC5: Food and water security | 3 | 1 | −0.9925 | 0.6101 | 2.6463 | 0.1038 | 0.371 | 0.112 | 1.225 | |

| IC6: Lack of education | 1 | 1 | −1.4048 | 0.4560 | 9.4921 | 0.0021 | 0.245 | 0.100 | 0.600 | |

| IC6: Lack of education | 3 | 1 | −0.7164 | 0.4271 | 2.8134 | 0.0935 | 0.489 | 0.212 | 1.128 | |

| EPC5: Easy access to politics | 1 | 1 | −3.1083 | 1.0609 | 8.5841 | 0.0034 | 0.045 | 0.006 | 0.357 | |

| EPC5: Easy access to politics | 3 | 1 | −0.7365 | 0.7668 | 0.9225 | 0.3368 | 0.479 | 0.107 | 2.152 | |

| EPC6: Engagement with the local communities | 1 | 1 | 0.9423 | 0.5172 | 3.3194 | 0.0685 | 2.566 | 0.931 | 7.071 | |

| EPC6: Engagement with the local communities | 3 | 1 | 0.0485 | 0.5065 | 0.0092 | 0.9237 | 1.050 | 0.389 | 2.833 | |

| EPC9: Evolution of hierarchical structures | 1 | 1 | −1.3520 | 0.4832 | 7.8281 | 0.0051 | 0.259 | 0.100 | 0.667 | |

| EPC9: Evolution of hierarchical structures | 3 | 1 | −1.2928 | 0.4713 | 7.5224 | 0.0061 | 0.275 | 0.109 | 0.691 | |

| EC1: Salary | 1 | 1 | −0.4062 | 0.4290 | 0.8964 | 0.0223 | 0.666 | 0.287 | 1.544 | |

| EC1: Salary | 3 | 1 | 0.4398 | 0.4158 | 1.1190 | 0.1632 | 1.552 | 0.687 | 3.507 | |

| PV3: Security | 1 | 1 | −0.9143 | 0.4850 | 3.5532 | 0.0594 | 0.401 | 0.155 | 1.037 | |

| PV3: Security | 3 | 1 | −0.3686 | 0.4742 | 0.6044 | 0.4369 | 0.692 | 0.273 | 1.752 | |

| PV5: Individual responsibility | 1 | 1 | −1.7312 | 0.5462 | 10.0444 | 0.0015 | 0.177 | 0.061 | 0.517 | |

| PV5: Individual responsibility | 3 | 1 | −0.8730 | 0.4967 | 3.0889 | 0.0788 | 0.418 | 0.158 | 1.106 | |

| PV9: Social success | 1 | 1 | −2.0763 | 0.6827 | 9.2487 | 0.0024 | 0.125 | 0.033 | 0.478 | |

| PV9: Social success | 3 | 1 | −1.7093 | 0.6531 | 6.8493 | 0.0089 | 0.181 | 0.050 | 0.651 | |

| PV10: Personal power | 1 | 1 | −4.2723 | 1.2286 | 12.0912 | 0.0005 | 0.014 | 0.001 | 0.155 | |

| PV10: Personal power | 3 | 1 | −1.4063 | 0.7209 | 3.8054 | 0.0511 | 0.245 | 0.060 | 1.007 | |

| CK: Cooperative knowledge | 1 | 1 | 1.7998 | 0.5134 | 12.2908 | 0.0005 | 6.049 | 2.211 | 16.545 | |

| CK: Cooperative knowledge | 3 | 1 | −0.9171 | 0.4431 | 4.2830 | 0.0385 | 0.400 | 0.168 | 0.953 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buendía-Martínez, I.; Hidalgo-López, C.; Brat, E. Are Cooperatives an Employment Option? A Job Preference Study of Millennial University Students. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177210

Buendía-Martínez I, Hidalgo-López C, Brat E. Are Cooperatives an Employment Option? A Job Preference Study of Millennial University Students. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177210

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuendía-Martínez, Inmaculada, Carolina Hidalgo-López, and Eric Brat. 2020. "Are Cooperatives an Employment Option? A Job Preference Study of Millennial University Students" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177210

APA StyleBuendía-Martínez, I., Hidalgo-López, C., & Brat, E. (2020). Are Cooperatives an Employment Option? A Job Preference Study of Millennial University Students. Sustainability, 12(17), 7210. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177210