Measuring What Is Not Seen—Transparency and Good Governance Nonprofit Indicators to Overcome the Limitations of Accounting Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

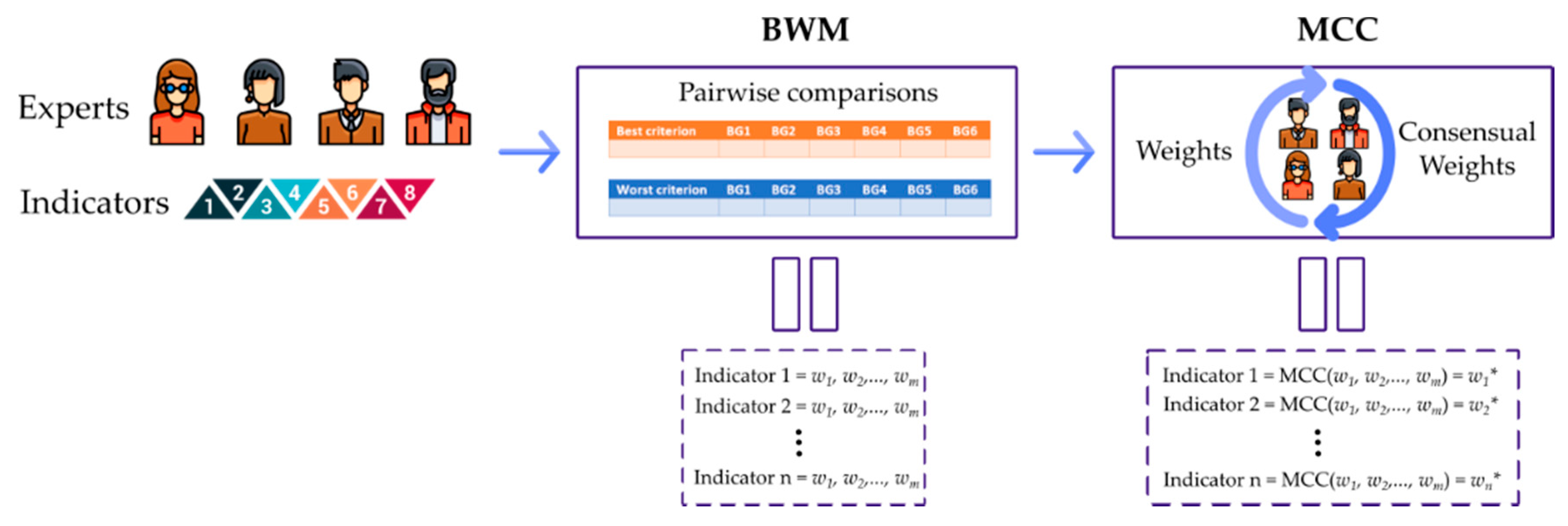

- A procedure for measuring transparency and good governance in NPOs through a multi-criteria group decision-making method.

- Application of BWM to weight indicators.

- Use of a consensus method to eliminate conflicts.

- Weighting of indicators according to their considered importance.

- Consensus on the power of the indicators.

- They unify the two main proposals of the Spanish case.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Contextualizing the Third Sector

2.2. Transparency and Good Governance in the NPOs

2.3. The Paradigm of Credibility in NPOs

2.4. The Insufficiency of Accounting Models: The Spanish Case

- The alliance formed by the NGO Platform for Social Action and the Coordinator of Development Cooperation Organizations. The NGO Platform for Social Action is a state, private, and professional organization that works to promote the development of social and civil rights for the most vulnerable and unprotected groups. The most recent data (referring to 2018) indicates that it encompasses 5716 entities. The Coordinator of Development Cooperation Organizations integrates more than 550 organizations, with the objective of establishing a cooperation policy that is consistent with the 2030 Agenda. It developed the Policy Coherence Index for Sustainable Development, a tool that aims to make visible the connections of one policy with others, and its impact on the environment and on human life. It also developed a common proposal with a total of 79 indicators that are divided into two main areas (transparency and good governance) which, in turn, are divided into thematic blocks.

- The mission of the Loyalty Foundation is to encourage society’s trust in NPOs to achieve an increase in donations, in addition to other forms of collaboration. It was the first entity to develop a methodology to analyse transparency and good governance in Spanish NPOs. Its experience has inspired other entities in Spain and Latin America. The Loyalty Foundation grants a certification to organizations that comply with the proposed principles, and provides independent information to private and institutional donors to assist them in their decisions. It presents a battery of 36 indicators subdivided into nine thematic areas.

3. Methodology

3.1. Best–Worst Method for Deriving Weights

- Define a set of criteria. In this study, the criteria are represented by the indicators used to measure the transparency and good governance in the NPOs.

- Select the best and the worst criterion, and , respectively. These are selected by experts individually and, if there are several or/and , the selection is made randomly.

- The best criterion is compared with the remaining criteria using a predefined scale. These comparisons result in the Best-to-Others (BO) vector, , in which means the preference of over the criterion .

- The worst criterion is compared with the remaining criteria using a predefined scale. These comparisons result in the Others-to-Worst (OW) vector, , in which means the preference of the criterion over .

- Compute the optimal criteria weights, which are derived from each pair and , where and , by means of the following non-linear programming model:where is obtained by minimizing the maximum absolute differences of and .

3.2. Minimum Cost Consensus for Consensual Weights

4. Discussion of Results

4.1. Selection of the Combination Battery of Indicators

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Analysis of the Results

4.3.1. Block 1: Transparency of the NPO Governing Board

4.3.2. Block 2: Appropriate Definition of the Mission, Vision, and Values

4.3.3. Block 3: Information Disclosure about Social Support and Donors

4.3.4. Block 4: Planning and Accountability

4.3.5. Block 5: Management Role of the NPO Governing Boards

4.3.6. Block 6: Appropriate Management Aligned with the Mission, Vision, and Values

4.3.7. Block 7: Strategical and Operational Planning

4.3.8. Block 8: Economic and Financial Management

4.3.9. Block 9: Human Resources Management

4.3.10. Block 10: Relationships and Communications with the Stakeholders

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amagoh, F. Improving the credibility and effectiveness of non-governmental organizations. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2015, 15, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.M.R.; Gil, M.I.S. Una nueva frontera en organizaciones no lucrativa. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2011, 71, 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanani, A.; Connolly, C. Non-governmental Organizational Accountability: Talking the Talk and Walking the Walk? J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 129, 613–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P.D.C.; Alcaide, T.C.H.; San Juan, A.I.S. La transparencia organizativa y económica en la Web de las fundaciones: Un estudio empírico para España. Revesco Rev. Estud. Coop. 2016, 121, 62–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, M.R.; Valencia, P.T.; Gutiérrez, A.C.M. Transparencia y calidad de la información económico-financiera en las entidades no lucrativas. Un estudio empírico a nivel andaluz. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2008, 63, 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Manville, G.; Greatbanks, R. Third Sector Performance: Management and Finance in Not-For-Profit and Social Enterprises; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781409429616. [Google Scholar]

- Greenlee, J.; Fischer, M.; Gordon, T.; Keating, E. An investigation of fraud in nonprofit organizations: Occurrences and deterrents. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2007, 36, 676–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.A.; McSwain, D. Financial disclosure management in the nonprofit sector: A framework for past and future research. J. Account. Lit. 2013, 32, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, E.K.; Frumkin, P. Reengineering nonprofit financial accountability: Toward a more reliable foundation for regulation. Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Rodríguez, C.; Licerán-Gutiérrez, A.; Moreno-Albarracín, A.L. Transparency as A Key Element in Accountability in Non-Profit Organizations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labella, A.; Liu, Y.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Martínez, L. Analyzing the performance of classical consensus models in large scale group decision making: A comparative study. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2018, 67, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.M.; Labella, Á.; De Tré, G. Martínez, L. A large scale consensus reaching process managing group hesitation. Knowl. Based Syst. 2018, 159, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares, I.; Estrella, F.J.; Martínez, L.; Herrera, F. Consensus under a fuzzy context: Taxonomy, analysis framework AFRYCA and experimental case of study. Inf. Fusion 2014, 20, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Arieh, D.; Easton, T. Multi-criteria group consensus under linear cost opinion elasticity. Decis. Support Syst. 2007, 43, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, L.M.; Sokolowski, S.W. Beyond Nonprofits: Re-conceptualizing the Third Sector. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2016, 27, 1515–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, I. Más allá del Estado del Bienestar. Nuevas tendencias en las políticas de bienestar en España: Implicaciones para las organizaciones sin ánimo de lucro; Ponencia presentada en el 19º Encuentro Anual de la Johns Hopkins Internacional Philanthropy Fellows: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marbán, V.; Rodríguez, G. Visión panorámica del tercer sector social en España: Entorno, desarrollo, investigación y retos sociales. Rev. Española Terc. Sect. 2008, 9, 13–40. [Google Scholar]

- Coraggio, J.L. Las tres corrientes vigentes de pensamiento y acción dentro del campo de la Economía Social y solidaria (ESS): Sus diferentes alcances. Univ. Nac. Gen. Sarmientoinst. Conurbano Argent. 2017, 15, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, S. What’s in a Name? Making Sense of Social Enterprise Discourses. Public Policy Adm. 2012, 27, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, C.M.M.; Raja, I.G. Medida de la eficiencia en entidades no lucrativas: Un estudio empírico para fundaciones asistenciales. Rev. Contab. Account. Rev. 2014, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lorenzo, F.C.; Ribal, C.B.; Yánez, J.S.N. Las dimensiones socioeconómicas del Tercer Sector en Canarias. CIRIEC-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2017, 89, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- González-Sánchez, M.; Rúa-Alonso, E. Análisis de la eficiencia en la gestión de las fundaciones: Una propuesta metodológica. Ciriec-España Rev. Econ. Pública Soc. Coop. 2007, 57, 117–149. [Google Scholar]

- Goncharenko, G. The accountability of advocacy NGOs: Insights from the online community of practice. Account. Forum 2019, 43, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urionabarrenechea, M.; Lage, C.; Arrizabalaga, E. Gestionar Con Calidad Las Entidades Sin Ánimo De Lucro: Hacia Una Eficacia, Eficiencia Y Economía En La Rendición De Cuentas. Quality Management of Non Profit Organizations: Towards Effectiveness. Rev. Estud. Empres. Segunda Época 2015, 1, 28–57. [Google Scholar]

- Perdomo, J.F. Las organizaciones no lucrativas: Necesidades de los usuarios de la información financiera. Rev. Española Del Terc. Sect. 2007, 6, 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- AECA. Indicadores para Entidades Sin Fines Lucrativos. Documento no 3. COMISIÓN DE ENTIDADES SIN FINES LUCRATIVOS; AECA: Madrid, Spain, 2012; ISBN 9788415467502. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlovic, J.; Lalic, D.; Djuraskovic, D. Communication of Non-Governmental Organizations via Facebook Social Network. Eng. Econ. 2014, 25, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fuertes-Fuertes, I.; Maset-Llaudes, A. numbers have been established to measure these comparisons in order to study the types of relationships existing between them. The results show that the Spanish NGOD sector is developing toward transparency. However, from a financial point of view, it is. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2007, 36, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Ye, T.; Zhang, Y. Does giving always lead to getting? Evidence from the collapse of charity credibility in China. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2019, 58, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, K. Understanding nonprofit transparency: The limit of formal regulation in the American nonprofit sector. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 18, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, G.D.; Guo, C. Accountability online: Understanding the web-based accountability practices of nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, D.J.; Simnett, R. Research horizons for public and private not-for-profit sector reporting: Moving the bar in the right direction. Account. Financ. 2019, 59, 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabedo, J.D.; Fuertes-Fuertes, I.; Maset-LLaudes, A.; Tirado-Beltrán, J.M. Improving and measuring transparency in NGOs: A disclosure index for activities and projects. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2018, 28, 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Striebing, C. Professionalization and voluntary transparency practices in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2017, 28, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, G.E. Transparency or Accountability? The Purpose of Online Technologies for Nonprofits. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 18, 7–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, L.M. Account space: How accountability requirements shape nonprofit practice. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2008, 37, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacon, R.; Walters, G.; Cornforth, C. Accountability in Nonprofit Governance: A Process-Based Study. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 46, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugerty, M.K.; Sidel, M.; Bies, A.L. Introduction to minisymposium: Nonprofit self-regulation in comparative perspective-themes and debates. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2010, 39, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, R.; Owens, T. Promoting transparency in the NGO sector: Examining the availability and reliability of self-reported data. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1263–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellens, L.; Jegers, M. Effective governance in nonprofit organizations: A literature based multiple stakeholder approach. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coule, T.M. Nonprofit governance and accountability: Broadening the theoretical perspective. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2015, 44, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, J.; Huybrechts, G.; Jegers, M.; Weijters, B.; Vantilborgh, T.; Bidee, J.; Pepermans, R. Nonprofit Governance Quality: Concept and Measurement. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 2012, 38, 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. Good Governance: A Radical and Normative Approach to Nonprofit Management. Voluntas 2014, 25, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, R.; Cornforth, C.; Aiken, M. The Governance Challenges of Social Enterprises: Evidence from a UK empirical study. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2009, 80, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, X.; Mueller, H.M. Corporate governance, product market competition, and equity prices. J. Financ. 2011, 66, 563–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.F. Mutual monitoring and corporate governance. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 45, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, J.; Guay, W. The use of equity grants to manage optimal equity incentive levels. J. Account. Econ. 1999, 28, 151–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, B.G. Los códigos de buen gobierno corporativo en las entidades sin ánimo de lucro: En especial en las fundaciones (Codes of good corporate governance in non-profit organizations: Especially in foundations). Oñati Socio-Leg. Ser. 2012, 2, 24–52. [Google Scholar]

- Benzing, C.; Leach, E.; McGee, C. Sarbanes-Oxley and the New Form 990: Are Arts and Culture Nonprofits Ready? Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 1132–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasadas, R.M.; Valencia, P.T. Responsabilidad social y transparencia a través de la Web: Un análisis aplicado a las cooperativas agroalimentarias españolas. Revesco Rev. Estud. Coop. 2014, 114, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Boubaker, S.; Cumming, D.; Nguyen, D.K. Research Handbook of Finance and Sustainability; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell, D.; Rutherford, A.C. Promoting charity accountability: Understanding disclosure of serious incidents. Account. Forum 2019, 43, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrés-Alonso, P.; Azofra-Palenzuela, V.; Romero-Merino, M.E. Determinants of Nonprofit Board Size and Composition. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2009, 38, 784–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Azzone, G.; Bengo, I. Performance Measurement for Social Enterprises. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2015, 26, 649–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Garcia, M.; Liket, K.; Alvarez-Gonzalez, L.I.; Maas, K. Back to Basics: Revisiting the relevance of beneficiaries and for evaluation and accountability in nonprofits. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2017, 27, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, H.P.; Raggo, P.; Bruno-van Vijfeijken, T. Accountability of transnational NGOs: Aspirations vs. practice. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 1175–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, G.C.; Vázquez, J.M.G.; Corredoira, M.D.L.Á.Q. La importancia de los stakeholders de la organización: Un análisis empírico aplicado a la empleabilidad del alumnado de la universidad española. Investig. Eur. Dir. Econ. Empres. 2007, 13, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, B.; Kearns, K. Accountability in Korean NPOs: Perceptions and Strategies of NPO Leaders. Voluntas 2015, 26, 1975–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. The Relationship of Nonprofits’ Financial Health to Program Outcomes: Empirical Evidence From Nonprofit Arts Organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2017, 46, 525–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, G.D.; Kuo, J.S.; Ho, Y.C. The Determinants of Voluntary Financial Disclosure by Nonprofit Organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, C.J.; Morgan, G.G. Special Issue on Charity Accounting, Reporting and Regulation. Volunt. Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2013, 24, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saaty, T.L. Group decision making and the AHP. Anal. Hierarchy Process 1989, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint, S.; Lawson, J.R. Rules for Reaching Consensus: A Modern Approach to Decision Making; Pfeiffer: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Labella, Á.; Martínez, L.; Rodríguez, R.M. Can classical consensus models deal with large scale group decision making? In Proceedings of the 2017 12th International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Knowledge Engineering (ISKE), Nanjing, China, 24–26 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Albarracín, A.L.; Licerán-Gutierrez, A.; Ortega-Rodríguez, C.; Labella, Á.; Rodríguez, R. Survey for Indicators. Available online: https://sinbad2.ujaen.es/sites/default/files/2020-07/Survey.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2020).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.44 | 1.00 | 1.63 | 2.30 | 3.00 | 3.73 | 4.47 | 5.23 |

| Batteries | No. Indicators |

|---|---|

| Indicators in the CONGDE battery | 79 |

| Indicators in the Loyalty Foundation battery with no equivalent aspects in the CONGDE one | 20 |

| FINAL VARIABLE (ITEMS) SELECTION | 59 |

| 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.048 | 0.191 | 0.380 | 0.382 |

| Institution 2 | 0.197 | 0.059 | 0.197 | 0.547 |

| Institution 3 | 0.316 | 0.051 | 0.316 | 0.316 |

| Institution 4 | 0.353 | 0.044 | 0.249 | 0.354 |

| Institution 5 | 0.169 | 0.048 | 0.185 | 0.597 |

| Consensus | 0.220 | 0.078 | 0.265 | 0.437 |

| 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.467 | 0.467 | 0.067 |

| Institution 2 | 0.245 | 0.669 | 0.086 |

| Institution 3 | 0.714 | 0.143 | 0.143 |

| Institution 4 | 0.532 | 0.096 | 0.372 |

| Institution 5 | 0.678 | 0.229 | 0.093 |

| Consensus | 0.574 | 0.276 | 0.150 |

| 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.123 | 0.046 | 0.246 | 0.126 | 0.337 | 0.122 |

| Institution 2 | 0.146 | 0.061 | 0.155 | 0.146 | 0.346 | 0.146 |

| Institution 3 | 0.105 | 0.083 | 0.105 | 0.247 | 0.080 | 0.381 |

| Institution 4 | 0.436 | 0.065 | 0.230 | 0.087 | 0.090 | 0.092 |

| Institution 5 | 0.140 | 0.052 | 0.145 | 0.140 | 0.145 | 0.378 |

| Consensus | 0.171 | 0.066 | 0.181 | 0.154 | 0.205 | 0.223 |

| 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 4.8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.089 | 0.089 | 0.212 | 0.178 | 0.153 | 0.089 | 0.153 | 0.038 |

| Institution 2 | 0.109 | 0.109 | 0.295 | 0.109 | 0.040 | 0.112 | 0.112 | 0.112 |

| Institution 3 | 0.174 | 0.119 | 0.281 | 0.073 | 0.050 | 0.159 | 0.072 | 0.072 |

| Institution 4 | 0.100 | 0.049 | 0.419 | 0.076 | 0.098 | 0.063 | 0.096 | 0.098 |

| Institution 5 | 0.088 | 0.288 | 0.088 | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.126 | 0.185 | 0.027 |

| Consensus | 0.112 | 0.129 | 0.263 | 0.107 | 0.088 | 0.110 | 0.124 | 0.067 |

| 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.196 | 0.196 | 0.095 | 0.052 | 0.095 | 0.270 | 0.095 |

| Institution 2 | 0.064 | 0.178 | 0.352 | 0.123 | 0.178 | 0.061 | 0.043 |

| Institution 3 | 0.090 | 0.051 | 0.359 | 0.045 | 0.051 | 0.090 | 0.314 |

| Institution 4 | 0.051 | 0.168 | 0.067 | 0.117 | 0.073 | 0.140 | 0.383 |

| Institution 5 | 0.055 | 0.032 | 0.105 | 0.204 | 0.204 | 0.344 | 0.055 |

| Consensus | 0.095 | 0.129 | 0.193 | 0.111 | 0.123 | 0.181 | 0.168 |

| 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.419 | 0.084 | 0.302 | 0.195 |

| Institution 2 | 0.085 | 0.491 | 0.212 | 0.212 |

| Institution 3 | 0.348 | 0.290 | 0.048 | 0.315 |

| Institution 4 | 0.138 | 0.086 | 0.649 | 0.127 |

| Institution 5 | 0.361 | 0.348 | 0.083 | 0.496 |

| Consensus | 0.286 | 0.251 | 0.206 | 0.257 |

| 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.096 | 0.253 | 0.154 | 0.096 | 0.154 | 0.096 | 0.058 | 0.096 |

| Institution 2 | 0.309 | 0.182 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.089 | 0.046 | 0.088 | 0.036 |

| Institution 3 | 0.090 | 0.154 | 0.154 | 0.090 | 0.154 | 0.022 | 0.179 | 0.158 |

| Institution 4 | 0.078 | 0.091 | 0.070 | 0.057 | 0.124 | 0.078 | 0.454 | 0.048 |

| Institution 5 | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.029 | 0.166 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.293 | 0.078 |

| Consensus | 0.148 | 0.172 | 0.109 | 0.110 | 0.117 | 0.061 | 0.197 | 0.086 |

| 8.1 | 8.2 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.6 | 8.7 | 8.8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.303 | 0.129 | 0.199 | 0.084 | 0.082 | 0.082 | 0.055 | 0.066 |

| Institution 2 | 0.220 | 0.181 | 0.225 | 0.037 | 0.087 | 0.053 | 0.053 | 0.144 |

| Institution 3 | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.166 | 0.190 | 0.095 | 0.166 | 0.024 | 0.027 |

| Institution 4 | 0.262 | 0.049 | 0.126 | 0.075 | 0.346 | 0.059 | 0.049 | 0.034 |

| Institution 5 | 0.047 | 0.209 | 0.226 | 0.095 | 0.173 | 0.173 | 0.031 | 0.046 |

| Consensus | 0.200 | 0.147 | 0.198 | 0.096 | 0.147 | 0.107 | 0.042 | 0.063 |

| 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 9.5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.085 | 0.215 | 0.215 | 0.269 | 0.215 |

| Institution 2 | 0.041 | 0.228 | 0.256 | 0.218 | 0.256 |

| Institution 3 | 0.184 | 0.306 | 0.282 | 0.183 | 0.045 |

| Institution 4 | 0.069 | 0.097 | 0.622 | 0.100 | 0.111 |

| Institution 5 | 0.302 | 0.118 | 0.118 | 0.411 | 0.050 |

| Consensus | 0.143 | 0.204 | 0.266 | 0.241 | 0.146 |

| 10.1 | 10.2 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 | 0.337 | 0.060 | 0.091 | 0.228 | 0.142 | 0.142 |

| Institution 2 | 0.151 | 0.107 | 0.053 | 0.107 | 0.431 | 0.151 |

| Institution 3 | 0.038 | 0.308 | 0.154 | 0.269 | 0.154 | 0.077 |

| Institution 4 | 0.506 | 0.075 | 0.173 | 0.104 | 0.083 | 0.059 |

| Institution 5 | 0.483 | 0.052 | 0.104 | 0.104 | 0.073 | 0.184 |

| Consensus | 0.339 | 0.111 | 0.115 | 0.162 | 0.150 | 0.123 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moreno-Albarracín, A.L.; Licerán-Gutierrez, A.; Ortega-Rodríguez, C.; Labella, Á.; Rodríguez, R.M. Measuring What Is Not Seen—Transparency and Good Governance Nonprofit Indicators to Overcome the Limitations of Accounting Models. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187275

Moreno-Albarracín AL, Licerán-Gutierrez A, Ortega-Rodríguez C, Labella Á, Rodríguez RM. Measuring What Is Not Seen—Transparency and Good Governance Nonprofit Indicators to Overcome the Limitations of Accounting Models. Sustainability. 2020; 12(18):7275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187275

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoreno-Albarracín, Antonio Luis, Ana Licerán-Gutierrez, Cristina Ortega-Rodríguez, Álvaro Labella, and Rosa M. Rodríguez. 2020. "Measuring What Is Not Seen—Transparency and Good Governance Nonprofit Indicators to Overcome the Limitations of Accounting Models" Sustainability 12, no. 18: 7275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187275

APA StyleMoreno-Albarracín, A. L., Licerán-Gutierrez, A., Ortega-Rodríguez, C., Labella, Á., & Rodríguez, R. M. (2020). Measuring What Is Not Seen—Transparency and Good Governance Nonprofit Indicators to Overcome the Limitations of Accounting Models. Sustainability, 12(18), 7275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187275