The Psychological Decision-Making Process Model of Giving up Driving under Parking Constraints from the Perspective of Sustainable Traffic

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

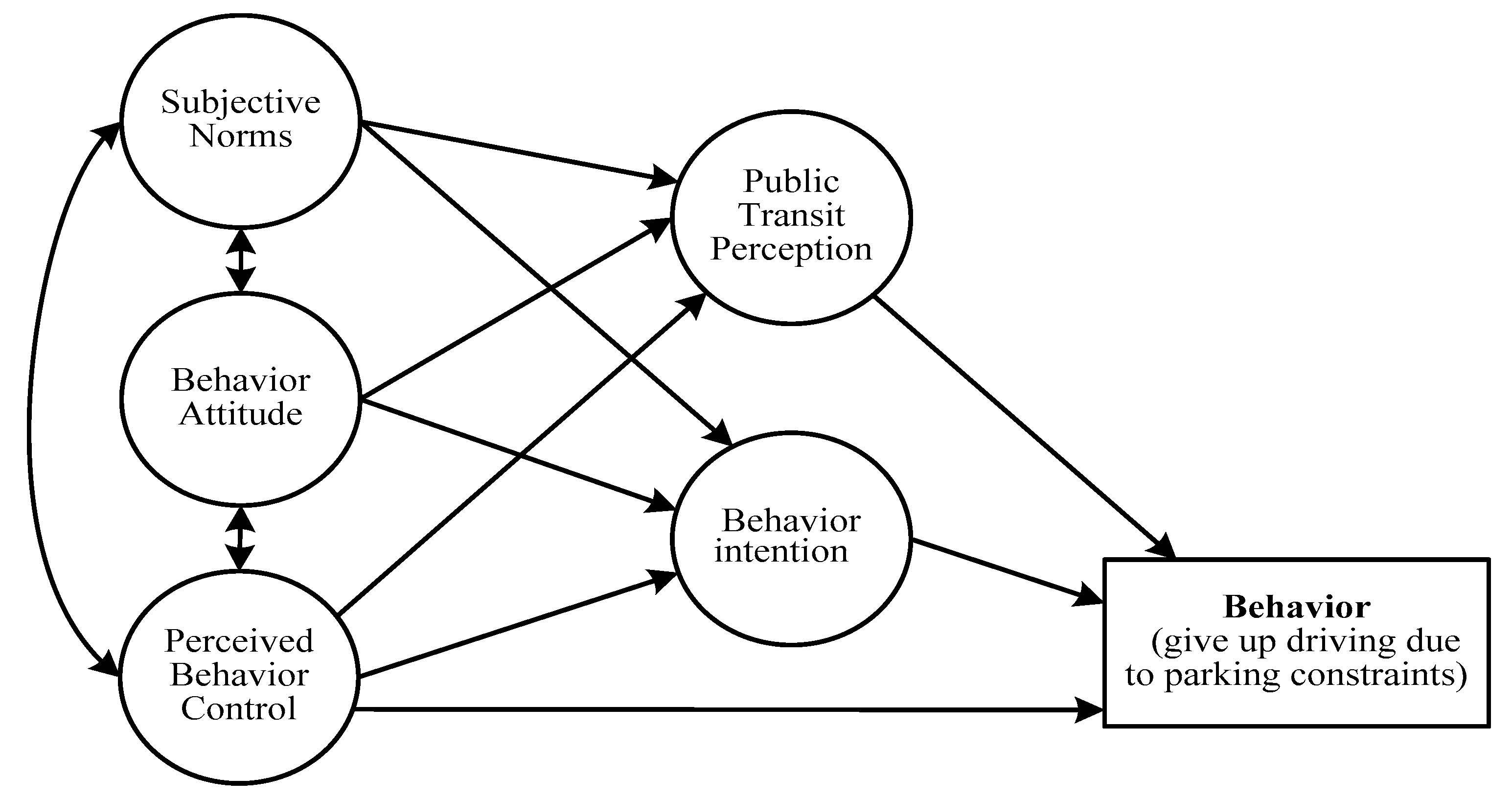

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis

2.2. Variable Settings

2.3. Data Sources

2.4. Analysis Methods

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Behavioral Preference

3.2. The Measurement Model

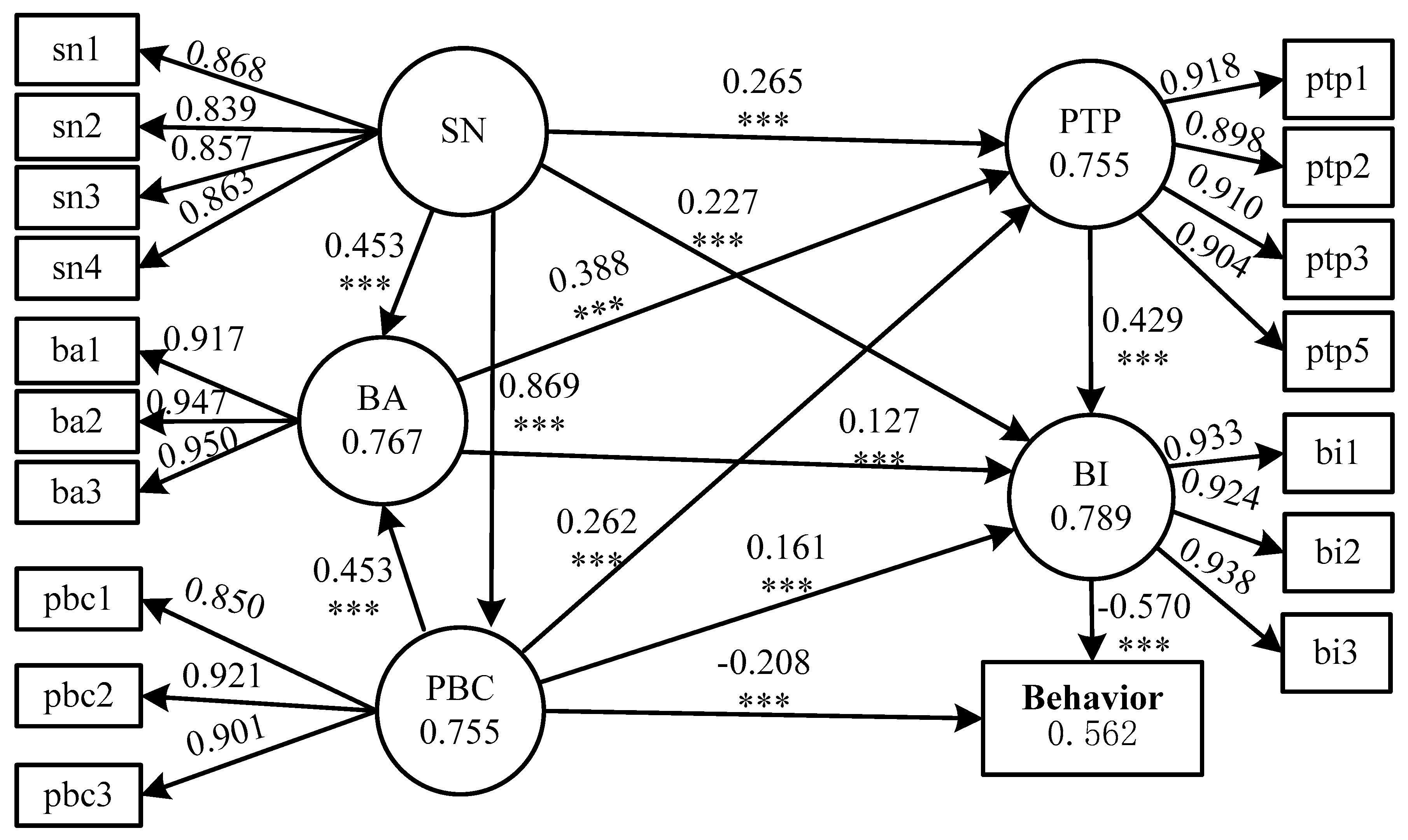

3.3. The Structural Model

4. Further Discussion

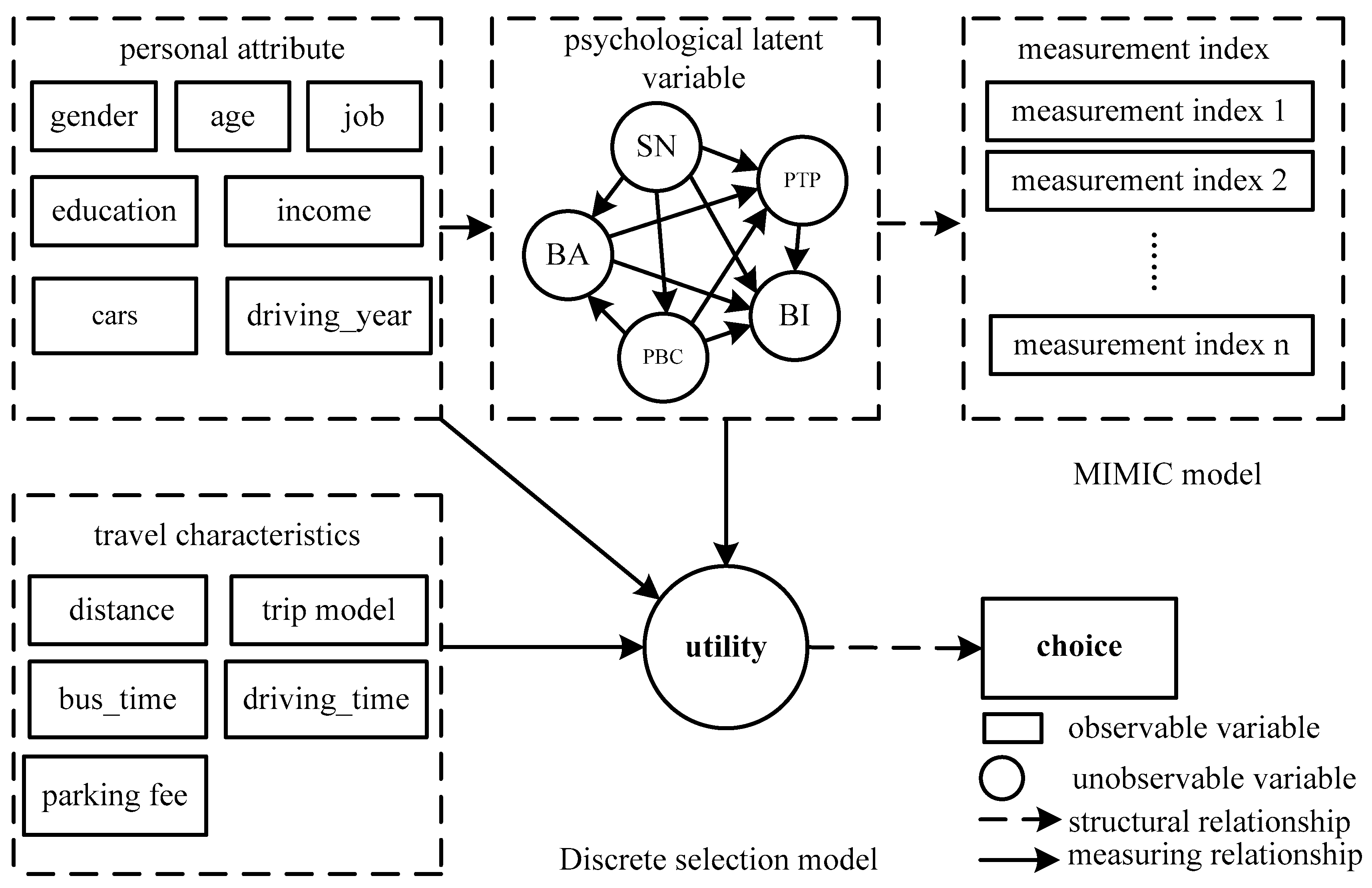

4.1. Establishment of Travel Behavior Model Considering Psychological Latent Variables

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Suggestions

- Enhance public awareness of parking supply. In reality, many residents who drive by themselves often complain about the lack of parking spaces, which results in negative psychology, and one of the main reasons is that residents do not have enough understanding of parking problems. Most ordinary citizens only pay attention to the convenience of parking and seldom analyze parking problems from the perspective of traffic and urban development. Therefore, it is necessary to make the following clear to the majority of car owners, through publicity and other means: As regards parking in the central area of the city, more spaces is not always a good thing, for too many parking spaces will induce more vehicles to enter the area and cause traffic congestion. Meanwhile, less parking spaces in the central area of the city may also be problematic, for too few parking spaces will cause a large number of vehicles to cruise on the road in search of parking spaces, which will also cause traffic jams. When city residents come to understand the problems concerning the supply of parking spaces, the negative emotions caused by parking will be reduced, and the change of travel mode due to parking restrictions will be changed from a completely passive behavior to an active choice. In this way, the effect of adjusting traffic demand through parking supply will be more obvious.

- Improve the level of public transit services in a targeted way. Car owners pay more attention to the rapidity and convenience of public transit (ptp1 and ptp3). When these factors meet their demands, they are more likely to give up driving due to insufficient parking supply. Time is the main factor of urban public transit to consider, including waiting time, transfer time and traveling time, etc.. The waiting time is related to the number of public transport and scheduling, transfer time is closely related to the completeness and layout of public transportation, driving time is associated with the performance and running routes of public transport. Then, it is necessary to establish a diversified public transit operation system and optimize the layout and scheduling, so as to reduce the travel time of public transport. At the same time, compared with self-driving travel, bus travel has a lower controllability, and timely access to bus operation information has become an important factor of concern. In an age of more and more advanced information, there are many ways and forms to solve this problem. For example, the public transit operation information can be released through electronic screens set up on platforms, navigation software, specialized applications and other ways to improve the convenience of travel for residents. In addition, compared with the use of public transit, self-driving travel has the obvious advantage of comfort. In order to improve the attraction of public transit, active measures should be taken to beautify the environment.

- Enhance the residents’ understanding of the economic value and social value of “giving up driving”. Research shows that the more travelers realize that giving up driving is a low-cost (ba1) behavior conducive to protecting the environment and alleviating traffic congestion (ba2, ba3), the more likely they are to give up driving due to parking constraints. Seen from the average of various measures of “behavior attitude”, in comparison, “giving up driving helps to reduce travel costs” has not been accepted by the majority of people. The main reason is that some travelers consider the cost of time, and even the possible cost increase caused by the inconvenience and lack of comfort of public transportation. Therefore, in order to enhance urban residents’ recognition of the economic value of “giving up self-driving travel”, it is necessary to focus on reducing residents’ travel costs from the perspective of time and convenience. Currently, the subway and rapid transit bus systems built in major cities can effectively solve this problem. On the other hand, in order to enhance urban residents’ awareness of the relationship between giving up self-driving travel and protecting the environment and easing traffic congestion, environmental protection publicity should be strengthened to guide people to deepen their understanding of giving up driving from the perspective of social value, and encourage people to take the initiative to reduce the use of cars.

- Creating a good social atmosphere. Whether car owners will give up driving due to parking restrictions is greatly influenced by the guidance of the government and their perceived behavior execution conditions (sn1, pbc2 and pbc3). Therefore, the government needs to take measures such as publicity work and fare concessions to actively encourage public transit. For example, it is necessary to strengthen the publicity when major public transport construction projects are completed, public transport operation conditions have been greatly improved, or there are important favorable public transport policies; or offer better bus fares or transport subsidies to residents who regularly travel by public transport. Moreover, the government can expand the publicity and guidance function of changing travel mode and green travel through the influence between people, so as to reach a consensus among the public on reducing the use of cars. In addition, relevant departments should also actively take measures to create conditions for car owners to change their travel modes.

- Carry out guidance work by groups and stages. The influence of individual attributes on latent variables indicates that the travel behavior intention and psychological decision-making process of different groups are different—for example, people with a large number of cars and a long driving age have a relatively weak intention to give up self-driving travel due to limited parking. Therefore, in order to improve the effect of adjusting traffic demand through parking supply, when implementing various auxiliary measures, we first need to group related areas within the scope of the residents. The aim is to give priority to guide the residents who have a positive attitude towards giving up driving to change the mode of travel, in order to achieve the goal of parking demand management. In addition, as various auxiliary measures mainly affect the psychological process of residents, it is not advisable to implement them overnight. In order not to arouse the aversion of residents, different measures should be implemented step by step.

6. Conclusions

- The choice of travel mode under the constraint of parking space is not only affected by individual social and economic attributes and travel mode characteristics, but also by psychological latent variables such as behavioral attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavior control, public transportation perception and behavior intention. In order to give full play to the positive role of parking supply in regulating traffic demand, appropriate auxiliary measures should be taken to enhance public awareness of parking supply, improve the level of public transport service, heighten residents’ understanding of the social value of “giving up driving” and create a good social atmosphere while optimizing the parking berth scale.

- The psychological factors influencing the choice of travel behavior under parking constraints are interrelated. The social pressure (subjective norms) experienced by car owners will influence the perceived behavioral ability (perceived behavioral control) and, together with it, impact on the understanding of the economic and social value of giving up driving (behavior attitude), This will then affect car owners’ perception of public transit and their behavior intention of giving up driving due to parking constraints. At the same time, car owners’ perception of public transit (increasing the willingness to travel by public transit due to the satisfaction of demands such as speed, convenience and service) will directly affect their behavior intention of giving up driving due to parking constraints.

- Through comparison, it is found that the ICLV model considering psychological latent variables has a higher fitting degree to empirical data than the traditional MNL model. In actual forecasting, considering the observable variables and an observation will lead to higher prediction accuracy. It is only necessary to consider the individual characteristics, travel time and so on to forecast the travel mode choice, and the requirement for data is not higher than that of the traditional MNL model, which is highly practical.

- This study mainly applies the theory of planned behavior in the continuous psychological model to discuss the psychological factors of travel behavior under parking constraints. In the future, it may be advisable to integrate other behavioral theories, such as the Normative Activation Theory, or theoretical model of stages to discuss the psychological decision-making process (e.g., self-adjusting behavioral change phase model) and explore more potential factors that may have an impact.

- This study takes commuting behavior as an example. In urban central areas, there may also be travel demands for official business, medical treatment, shopping, entertainment, etc., and there may be differences in the influence relationship of behavior intentions under different travel purposes. In order to better understand the influence factors of car owners giving up driving under parking constraints, future research can analyze different travel purposes and dig deeper into the universal laws of travel behavior decision-making, so as to provide a decision-making reference for urban parking supply optimization and travel structure optimization, and contribute to the sustainable development of urban traffic.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Report on the Environment: Nitrogen Oxide Emissions; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/roe/indicator_pdf.cfm?i=15 (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Morrall, J.M.; Bolger, D. The relationship between downtown parking supply and transit use. ITE J. 1996, 2, 32–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, B.; Abraham, C. What drives car use? A grounded theory analysis of commuters’ reasons for driving. Transp. Res. Part F 2007, 10, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Friman, M.; Gärling, T. Stated reasons for reducing work-commute by car. Transp. Res. Part F 2008, 11, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroesen, M. Modeling the behavioral determinants of travel behavior: Application of latent transition analysis. Transp. Res. Part A 2014, 65, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.L.; Liu, T.L.; Huang, H.J. On the morning commute problem with carpooling behavior under parking space constraint. Transp. Res. Part B 2016, 91, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, O.A. A stochastic transit assignment model considering differences in passengers utility functions. Transp. Res. Part B 2000, 34, 377–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Ritamura, R. What does a one-month free bus ticket do to habitual drivers? Transportation 2003, 7, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, P.; Juan, Z.C.; Zha, Q.F. Incorporating psychological latent variables into travel choice model. China J. Highw. Transp. 2014, 27, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Akiva, M.; Mcfadden, D.; Train, K.; Bhat, C.; Bierlaire, M.; Bolduc, D.; Boersch-Supan, A.; Brownstone, D.; Bunch, D.S.; Daly, A.; et al. Hybrid choice models: Progress and challenges. Mark. Lett. 2002, 13, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.V.; Heldt, T.; Johansson, P. The effects of attitudes and personality traits on mode choice. Transp. Res. Part A 2006, 40, 507–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeid, M.A. Measuring and Modeling Activity and Travel Well-Being; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, K.M.N.; Zaman, H. Effects of incorporating latent and attitudinal information in mode choice models. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2012, 35, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Transportation Statistics. National Household Travel Survey Daily Travel Quick Facts; Bureau of Transportation Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.bts.gov/statistical-products/surveys/national-household-travel-survey-daily-travel-quick-facts (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- U.S. Department of Transportation. Table 1-42: Average Annual PMT, VMT Person Trips and Trip Length by Trip Purpose; National Household Travel Survey: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.bts.gov/content/average-annual-pmt-vmt-person-trips-and-trip-length-trip-purpose (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, P.; Khan, S.A. Shedding light on the psychological and behavioral determinants of travel mode choice: A meta-analysis. Transp. Res. Part F 2017, 48, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaris, L.; Danielis, R. The impact of transportation demand management policies on commuting to college facilities: A case study at the University of Trieste, Italy. Transp. Res. Part A 2014, 67, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.L.; Liang, Z.L.; Chen, Q. When will car owners abandon car driving? Analysis based on a survey of the parking experiences of people in Changsha, China. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2019, 33, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell’Olio, L.; Ibeas, A.; Cecin, P. The quality of service desired by public transport users. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrinopoulos, Y.; Antoniou, C. Public transit user satisfaction: Variability and policy implications. Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, J.M.; Benitez, F.G. A Methodology for modeling and identifying users satisfaction issues in public transport systems based on users surveys. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 54, 1104–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingardo, G.; van Wee, B.; Rye, T. Urban parking policy in Europe: A conceptualization of past and possible future trends. Transp. Res. Part A 2015, 74, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Code | Variable Name | Index Code | Measurement Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| BA | Behavior attitude | ba1 | Giving up driving helps to reduce travel costs. |

| ba2 | Giving up driving is beneficial to environmental protection. | ||

| ba3 | Giving up driving is conducive to easing traffic congestion. | ||

| SN | Subjective norms | sn1 | The government often encourages public transit. |

| sn2 | Family, friends and colleagues often complain about the difficulty of parking. | ||

| sn3 | If one of your family, friends or colleagues takes the public transit instead, you will also give up driving. | ||

| sn4 | If your family, friends or colleagues persuade you to take the public transit, you will give up driving. | ||

| PBC | Perceived behavior control | pbc1 | It is not difficult for you to give up driving. |

| pbc2 | You will decide whether to give up driving according to the parking conditions. | ||

| pbc3 | You will decide whether to give up driving according to the public transit service level. | ||

| PTP | Public transit perception | ptp1 | Prefer to travel by public transit due to short waiting time and transfer time. |

| ptp2 | Prefer to travel by public transit due to short journey time. | ||

| ptp3 | Prefer to travel by public transit due to high information transparency of vehicle status. | ||

| ptp4 | Prefer to travel by public transit due to the stable running time and good punctuality. | ||

| ptp5 | Prefer to travel by public transit due to the cleanliness and comfort of the vehicle. | ||

| BI | Behavior intention | bi1 | Give up driving because it takes too long to search for a parking space. |

| bi2 | Give up driving because walking distance is too long after parking. | ||

| bi3 | Give up driving because the whole parking process takes too long. |

| Variables | Sorts | Assignment | Percentage (%) | Variables | Sorts | Assignment | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 1 | 47.5 | Distance (km) | <5 | 1 | 32.9 |

| Male | 2 | 52.5 | 5–10 | 2 | 30.4 | ||

| Age | <30 | 1 | 38.8 | 10–20 | 3 | 24.2 | |

| 31–40 | 2 | 40.1 | >20 | 4 | 13.4 | ||

| 41–50 | 3 | 17.5 | Trip model | Go straight to work | 1 | 83.1 | |

| >50 | 4 | 3.6 | other activities on the way | 2 | 16.9 | ||

| Job | civil servants | 1 | 14.5 | Bus time | <15 min | 1 | 14.6 |

| Public Institution personnel | 2 | 19.7 | 15–30 min | 2 | 25.1 | ||

| Enterprise staff | 3 | 34.5 | 0.5–1 h | 3 | 35.4 | ||

| Private owner | 4 | 13.7 | 1–1.5 h | 4 | 16.1 | ||

| Others | 5 | 17.6 | >1.5 h | 5 | 8.8 | ||

| Education | Junior and below | 1 | 1.8 | Driving time | <15 min | 1 | 32.8 |

| High school or Vocational School | 2 | 7.6 | 15–30 min | 2 | 37.9 | ||

| Junior or Undergraduate | 3 | 71.5 | 0.5–1 h | 3 | 22.8 | ||

| Master and above | 4 | 19.1 | 1–1.5 h | 4 | 5.1 | ||

| Income (unit: thousand Chinese Yuan) | <50 | 1 | 9.0 | >1.5 h | 5 | 1.3 | |

| 50–100 | 2 | 29.0 | Parking fee (unit: Chinese Yuan) | free | 1 | 44.6 | |

| 100–200 | 3 | 28.7 | <5 | 2 | 18.8 | ||

| 200–300 | 4 | 16.3 | 5–10 | 3 | 24.0 | ||

| >300 | 5 | 17.2 | 10–15 | 4 | 6.6 | ||

| Cars | 1 | 1 | 68.5 | >15 | 5 | 6.0 | |

| 2 | 2 | 28.5 | |||||

| >3 | 3 | 3.0 | |||||

| Driving year | <3 | 1 | 27.8 | ||||

| 3–5 | 2 | 23.4 | |||||

| 5–10 | 3 | 28.1 | |||||

| >10 | 4 | 20.7 |

| Behavior | Situation | Option | Assignment | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | How long must it take to find a suitable parking space before you give up driving? | 10 min. | 1 | 51.0 |

| 15 min. | 2 | 34.1 | ||

| 20 min. | 3 | 14.9 | ||

| B2 | How far must the walking distance after parking be for you to give up driving? | 200 m | 1 | 39.4 |

| 400 m | 2 | 39.4 | ||

| 600 m | 3 | 21.2 | ||

| B3 | How long must the total parking time be for you to give up driving? | 15 min. | 1 | 41.9 |

| 20 min. | 2 | 37.6 | ||

| 25 min. | 3 | 20.4 |

| Psychological Latent Variables | Measurement Index | Mean | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | ba1 | 3.46 | 0.917 | 0.931 | 0.956 | 0.880 |

| ba2 | 3.78 | 0.947 | ||||

| ba3 | 3.73 | 0.950 | ||||

| SN | sn1 | 3.64 | 0.868 | 0.880 | 0.917 | 0.734 |

| sn2 | 3.62 | 0.839 | ||||

| sn3 | 3.14 | 0.857 | ||||

| sn4 | 3.23 | 0.863 | ||||

| PBC | pbc1 | 3.36 | 0.850 | 0.870 | 0.920 | 0.794 |

| pbc2 | 3.73 | 0.921 | ||||

| pbc3 | 3.53 | 0.901 | ||||

| PTP | ptp1 | 3.90 | 0.918 | 0.929 | 0.949 | 0.824 |

| ptp2 | 3.72 | 0.898 | ||||

| ptp3 | 3.78 | 0.910 | ||||

| ptp5 | 3.77 | 0.904 | ||||

| BI | bi1 | 3.82 | 0.933 | 0.924 | 0.952 | 0.868 |

| bi2 | 3.65 | 0.924 | ||||

| bi3 | 3.71 | 0.938 |

| BA | BI | PBC | PTP | SN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | 0.938 | ||||

| BI | 0.813 | 0.931 | |||

| PBC | 0.847 | 0.818 | 0.891 | ||

| PTP | 0.835 | 0.853 | 0.820 | 0.908 | |

| SN | 0.847 | 0.826 | 0.869 | 0.821 | 0.857 |

| −0.202 *** | −0.130 *** | −0.157 *** | −0.118 *** | −0.156 *** | |

| 0.107 ** | - | 0.161 *** | 0.119 *** | 0.137 *** | |

| −0.113 *** | −0.111 *** | −0.106 *** | −0.159 *** | −0.143 *** | |

| −0.268 *** | −0.294 *** | −0.290 *** | −0.254 *** | −0.253 *** | |

| - | - | −0.146 *** | −0.104 ** | −0.191 *** |

| MNL Model without Latent Variables | ICLV Model with Latent Variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 20 min | 15 min | 20 min | |

| Constant | - | - | 4.651 ** | - |

| = 1 | 1.657 ** | 3.311 *** | - | - |

| = 2 | - | 2.502 ** | - | - |

| = 1 | 1.608 *** | 1.399 ** | - | - |

| = 1 | 1.535 *** | 0.971 * | - | - |

| = 2 | 1.177 ** | - | - | - |

| = 1 | - | - | −1.285 * | - |

| = 1 | 4.697 *** | 3.465 *** | 3.912 *** | 2.907 *** |

| = 2 | 4.274 *** | 3.685 *** | 3.733 *** | 3.260 *** |

| = 3 | 2.985 *** | 2.506 *** | 2.669 *** | 2.204 *** |

| = 4 | 1.263 * | 1.38 ** | 1.134 ** | 1.254 ** |

| = 1 | −4.127 *** | −4.474 *** | −3.982 *** | −4.230 *** |

| = 2 | −3.5477 ** | −3.667 *** | −3.041 ** | −3.209 * |

| = 3 | - | −2.863 * | - | −2.263 * |

| - | - | 6.057 *** | 2.962 * | |

| - | - | −4.728 ** | −2.037 * | |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.269 | 0.318 | ||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shuangli, P.; Guijun, Z.; Qun, C. The Psychological Decision-Making Process Model of Giving up Driving under Parking Constraints from the Perspective of Sustainable Traffic. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177152

Shuangli P, Guijun Z, Qun C. The Psychological Decision-Making Process Model of Giving up Driving under Parking Constraints from the Perspective of Sustainable Traffic. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177152

Chicago/Turabian StyleShuangli, Pan, Zheng Guijun, and Chen Qun. 2020. "The Psychological Decision-Making Process Model of Giving up Driving under Parking Constraints from the Perspective of Sustainable Traffic" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177152

APA StyleShuangli, P., Guijun, Z., & Qun, C. (2020). The Psychological Decision-Making Process Model of Giving up Driving under Parking Constraints from the Perspective of Sustainable Traffic. Sustainability, 12(17), 7152. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177152