Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Sustainability Playing a Critical Role in Prosperity

2.2. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Global Context

“The creation of coordinated supply chains through the voluntary integration of economic, environmental, and social considerations with key inter-organizational business systems designed to efficiently and effectively manage the material, information, and capital flows associated with the procurement, production, and distribution of products or services in order to meet stakeholder requirements and improve the profitability, competitiveness, and resilience of the organization over the short- and long-term”.(p. 339)

2.3. Emerging Economies and Sustainable Supply Chain Management

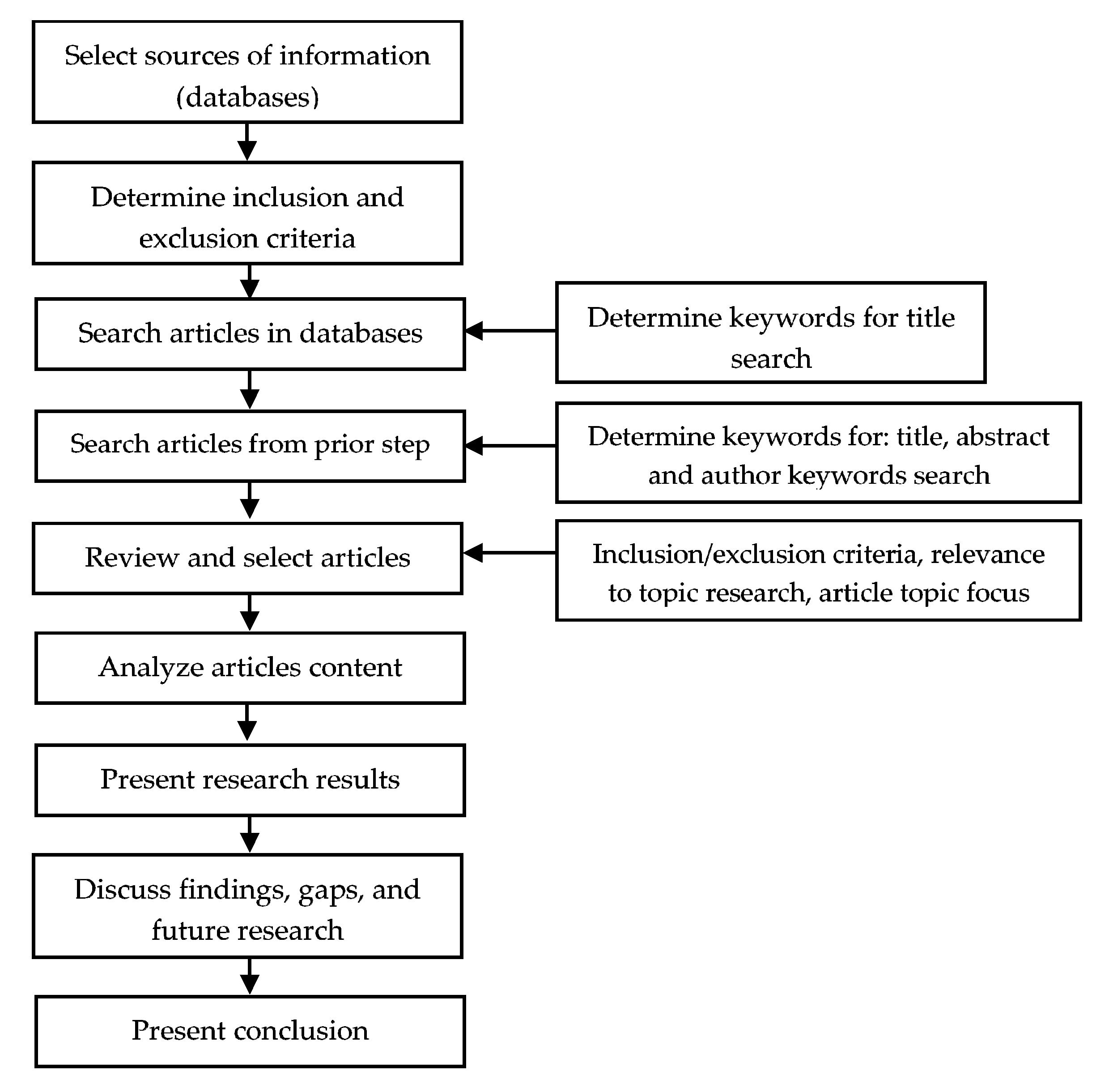

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sources of Information, and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.2. Keywords Definition and Articles Search

3.3. Articles Review and Selection

3.4. Articles Analysis and Results

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

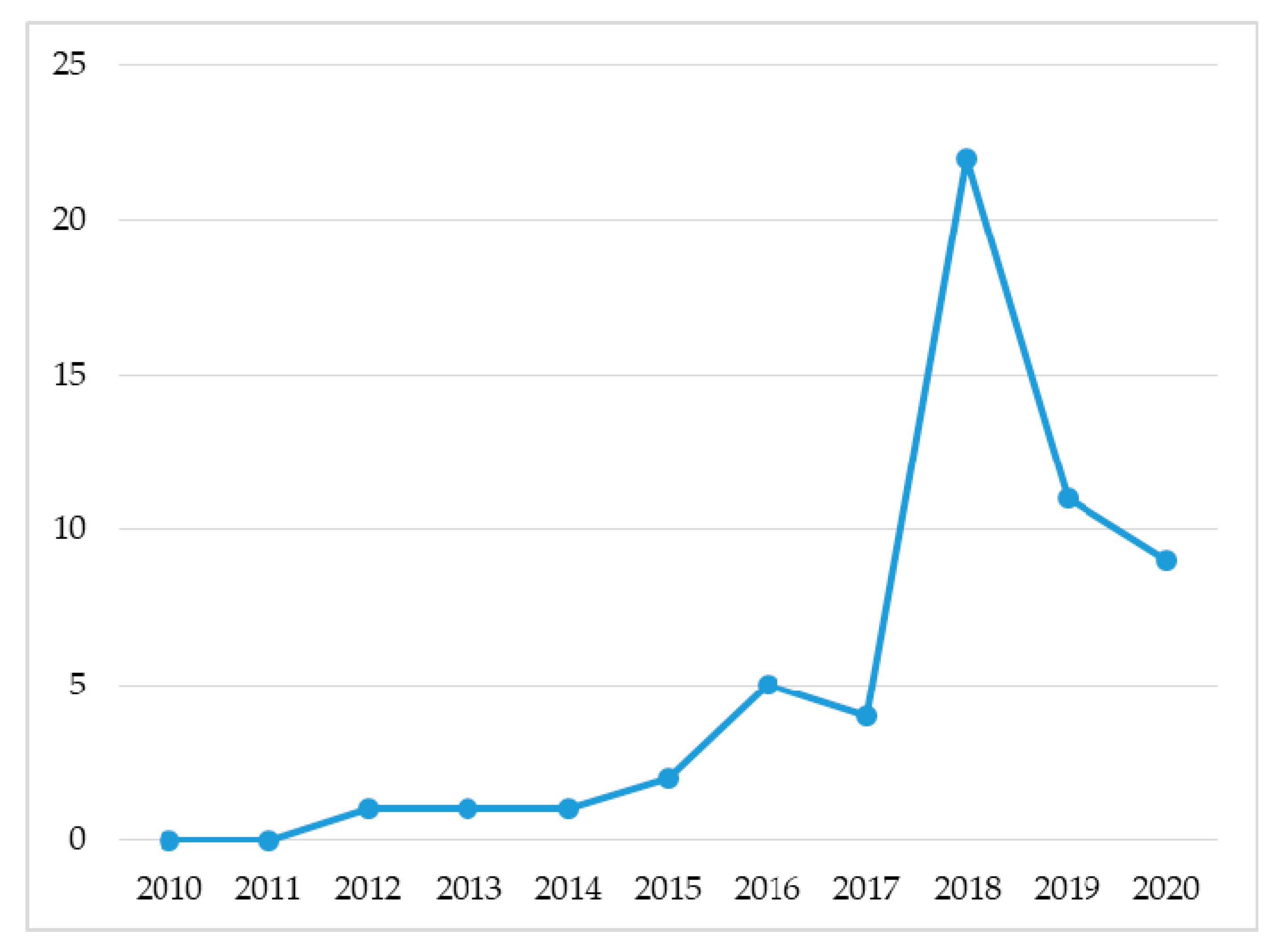

4.1.1. Analysis of Articles by Year of Publication

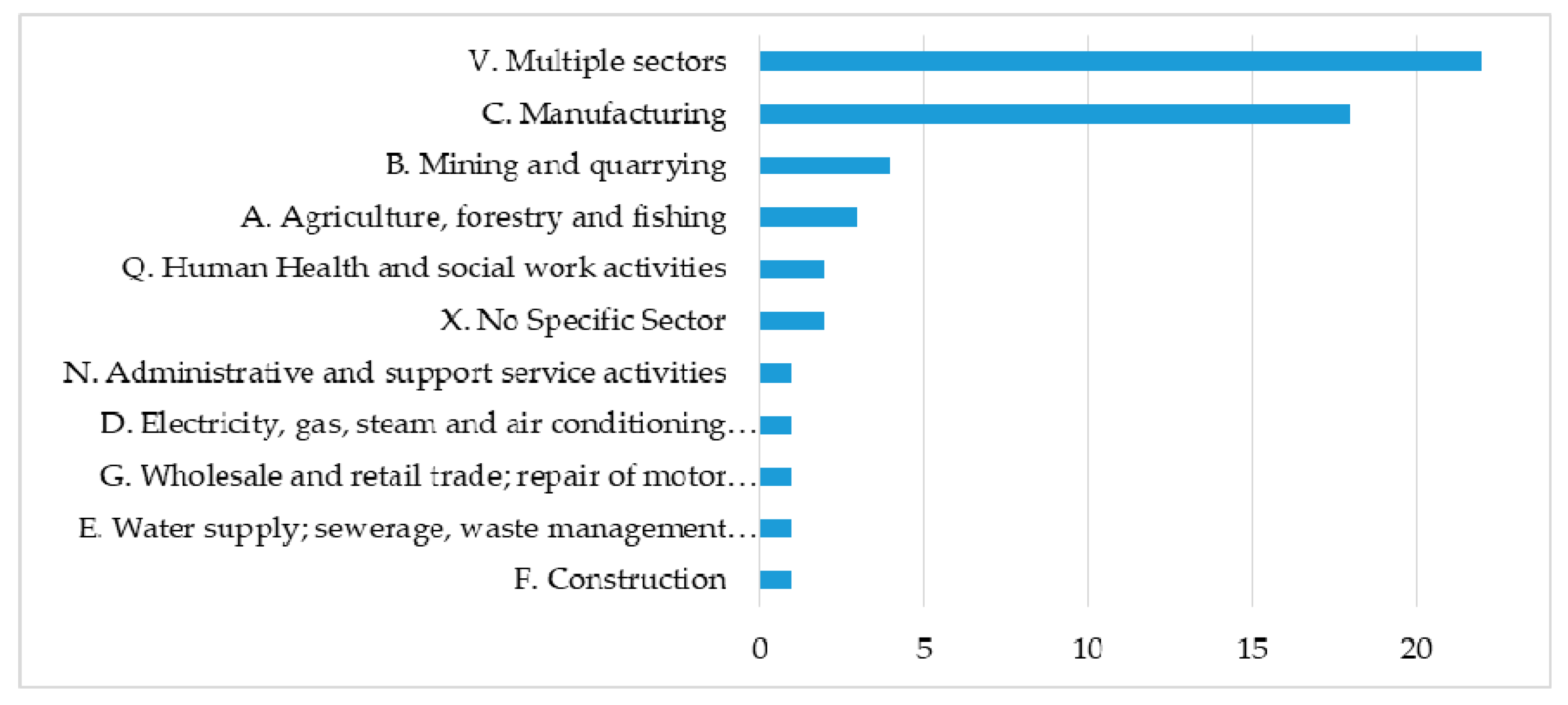

4.1.2. Analysis of Articles by Industry Sector

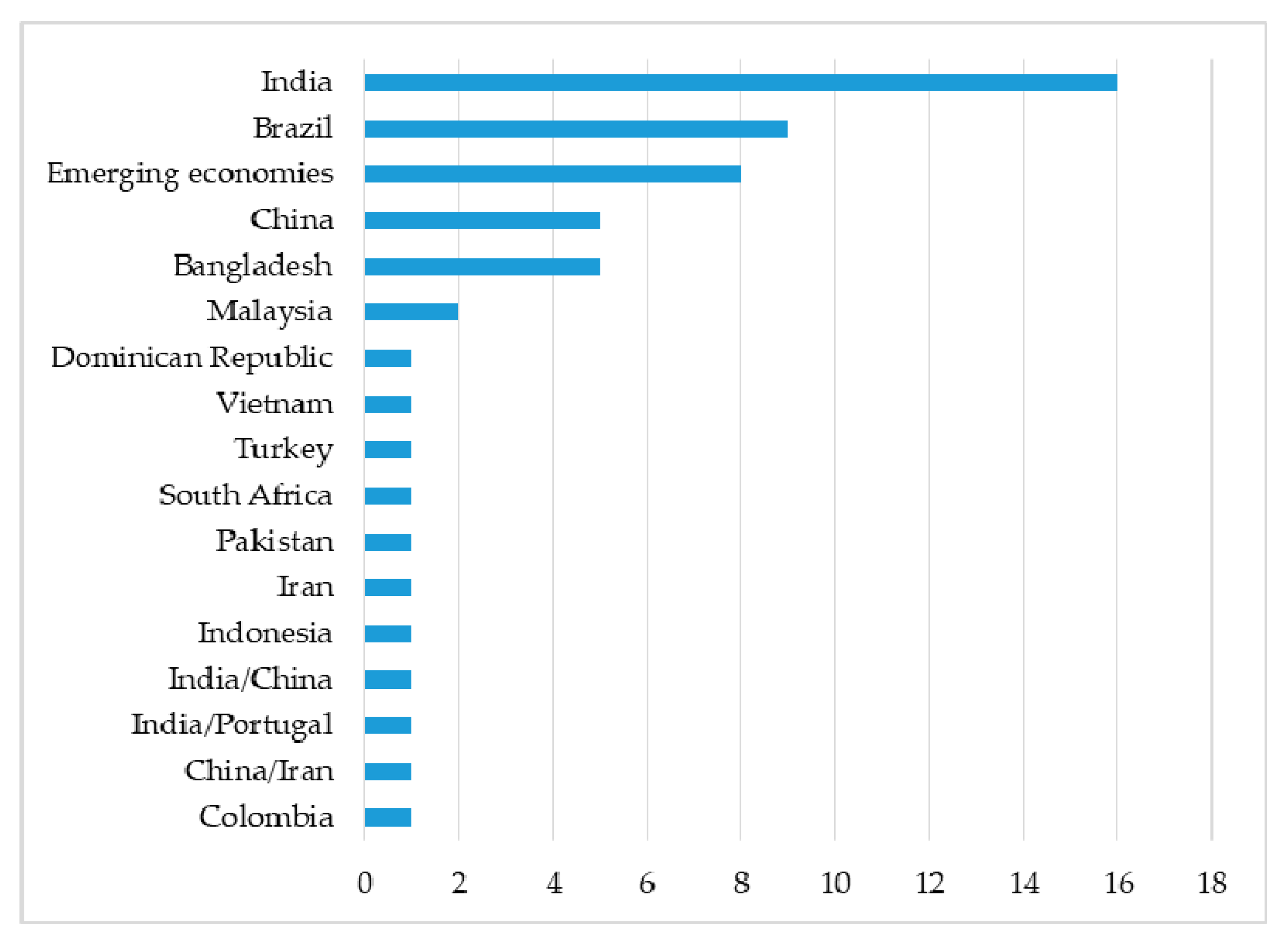

4.1.3. Analysis of Articles by Researched Country

4.1.4. Analysis of Research Methodologies

4.2. Content Analysis

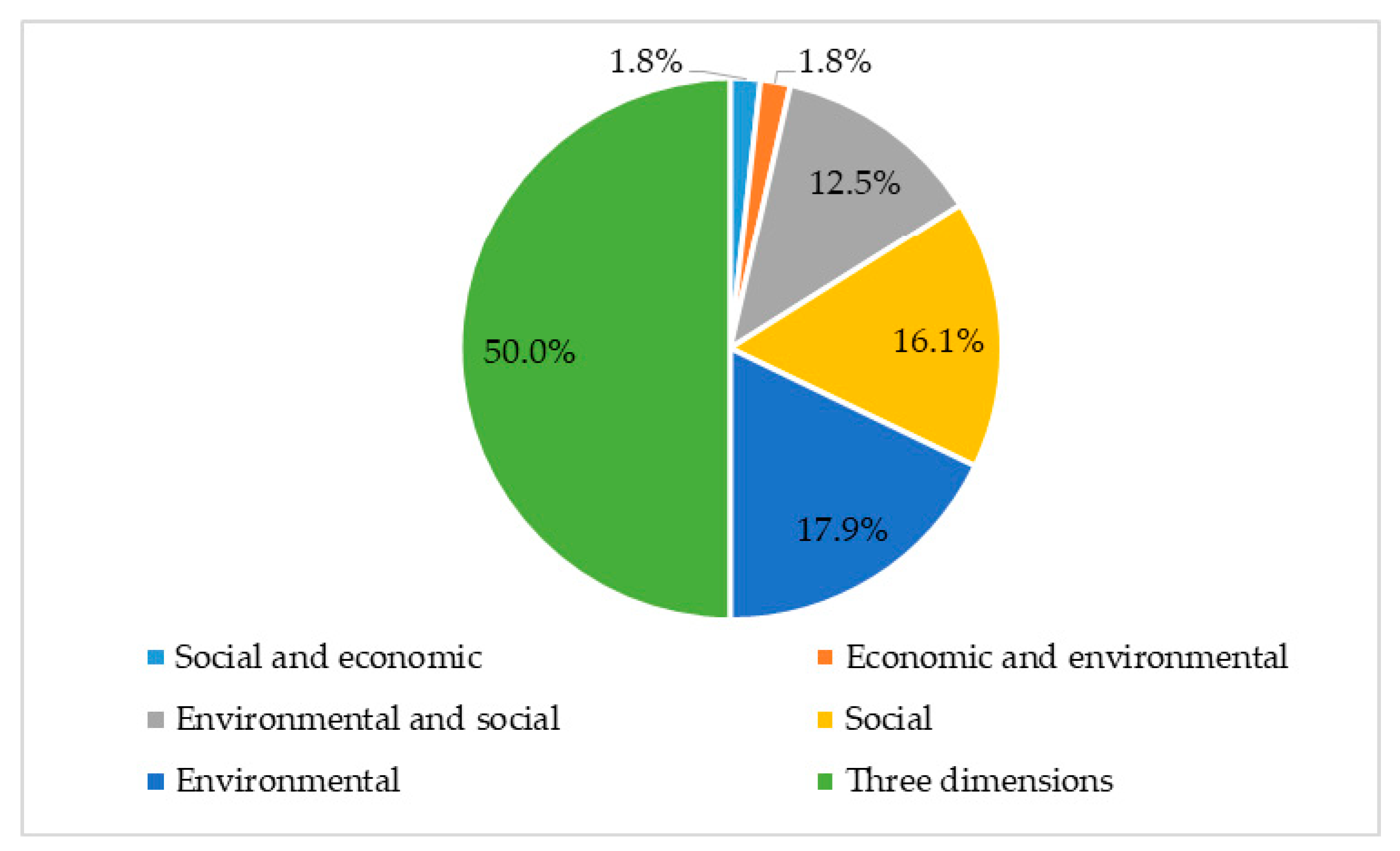

4.2.1. Sustainable Dimensions

4.2.2. Environmental Dimension

4.2.3. Economic Dimension

4.2.4. Social Dimension

4.2.5. Combination of Dimensions

4.2.6. Models on Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Economies

5. Discussion

5.1. The Findings

- ➢

- Researchers and practitioners have become increasingly aware and interested in sustainable supply chains in emerging economies; however research findings show that although developing countries are playing a key role in global markets, the concept of a sustainable supply chain is new to many of the supply chain players [123]. This review found SSCM research for emerging countries is behind in research on SSCM globally. It could be argued that interest in SSCM in emerging economies has taken place years after the research of SSCM itself has started. Nevertheless, the pressure from customers, government, and nongovernmental organizations, has made sustainable development become an essential and challenging assignment in the new ways of doing business [124].

- ➢

- The research on SSCM in emerging economies is led by empirical research methodologies, with 63% of the 56 articles, which include structured and semi-structured surveys and interviews through questionnaires, in person or by mail. Tebaldi, Bigliardi and Bottani [22] also found empirical surveys to be the most popular applied methodology when researching SSC and innovation. On the other hand, Ansari and Kant [21] findings revealed SSC research was dominated by qualitative research like case studies and conceptual/theoretical models and highlighted the need for more empirical and quantitate research.

- ➢

- Articles are using a mixed method approach to answer research questions. Researchers have used qualitative and quantitative methods for data collection and analysis. This approach can enhance the perspectives of the investigation and provide different perception on the topics being discussed. Luthra and Mangla [35] used interpretive structural modelling (ISM) methodology integrated with fuzzy MICMAC within a qualitative nature of research. Motevali Haghighi, Torabi and Ghasemi [12] used data envelopment analysis (DEA) for sustainable supply chains performance assessment, but including quantitative and qualitative indicators.

- ➢

- A diversity of SSCM related topics have been addressed, such as Base of the Pyramid (BoP), enablers and barriers, innovation, collaboration with suppliers, leadership and multi-tier/suppliers initiatives, SSC practices and processes, influential indicators for sustainable development, SSC metrics and indicators, environmental impact assessment, etc.

- ➢

- Structural equation modeling (SEM) is the most used technique for analysis (9 articles), followed by data analysis (eight), and partial least squares (PLS) (five). SEM has been combined, in several cases, with PLS (PLS-SEM) [40,90,113] or covariance-based (CB-SEM) [83,86], and it is used when series of regression analyses are required [125]. Also, Zeng, et al. [126] used SEM in empirical research, to study the relationships between institutional pressure, supply chain relationship management, circular economic capacity, and SSC design from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. Furthermore, Paulraj, et al. [127] used SEM to examine the links between business motives, SSCM practices and the performance of the business using a sample of companies in Germany.

- ➢

- Thirty-nine percent of the studies are conducted in multiple sectors, as it gives a more general idea on SSCM in emerging economies, followed by the fashion/textile/apparel sector (11%), the oil/gas/petrochemical/power/electric power sector (9%), the automotive sector (7%) and the food sector (7%). India is the most researched country (32%), followed by Brazil (14.3%), China (10.7%), and Bangladesh (8.9%).

- ➢

- Several sustainability measures have been presented in the literature to recognize the sustainability of supply chains helping stakeholders in making strategic decisions [128]. Mani, Agarwal, Gunasekaran, Papadopoulos, Dubey and Childe [114] discussed and proposed 20 supply chain social sustainable measures across multiple sectors in India, under six fundamental indicators: Equity, philanthropy, safety, health and welfare, ethics, and human rights. Furthermore, Mani, Gunasekaran and Delgado [86] explored social issues related to suppliers and identified measures associated with social sustainability in emerging economies. The findings showed there is a positive relationship between suppliers’ social sustainability practices and supply chain performance. It is a challenge to analyze sustainable development indicators, however, managers need to evaluate SSCM performance in specific sectors in emerging economies [84].

- ➢

- Environmental sustainability in emerging economies is taking a primary stand in supply chain operation, due to natural resources consumption, labor intensive operations [129] and all the logistics involved in delivering the manufactured products [103]. Suhi, Enayet, Haque, Ali, Moktadir and Paul [98] provided a framework on environmental sustainability indicators identification and evaluation for Bangladesh industries. Furthermore, the environmental impact is different based on the resources consumed, and there is a dearth of studies, in emerging economies, on how to evaluate the resources consumption throughout the supply chain and mitigation strategies to overcome it [106]. Nonetheless, increasing concern on social issues and practices in emerging economies is present, even though research is still new to the research field [28].

- ➢

- Collaboration in supply chain plays an essential role for sustainable development achievement [69]. However, in emerging economies it is suggested that it may not always be “good” because in some instances it could increase the risk of corruption [130]. On the other hand, de Vargas Mores, Finocchio, Barichello and Pedrozo [91] findings revealed that collaboration between the focal organization and other supply chain parties is essential for sustainable development. Even external stakeholders play an important role in SC collaboration, since they can be a source of risk if their concerns are not taken into account [69]. Beske and Seuring [118] identified collaboration as a key category of high importance for sustainable management of supply chains, from operational and structural perspectives, helping to achieve competitive advantage and reduce overall cost and uncertainty. Campos, Straube, Wutke and Cardoso [27] argued that there is evidence of collaboration opportunities between countries in response to enhance global sustainability performance. A critical subject in supply chain collaboration then, is the distinct interests that can exist in each participant and achieving the overall success of the chain [104]. From a global perspective, prior researchers have found differences in SSC practices implemented by developed and developing countries [131].

- ➢

- Innovation topics in sustainable supply chain practices in emerging economies is needed. As the markets evolve and competition is global, emerging economies operational capabilities become crucial, and sustainable innovation plays a key role in this context. Silva, et al. [132] findings showed product and process innovation enhance sustainability performance, including green supply chain practices. Managers now need to consider sustainability issues when adopting new technologies, Industry 4.0, and innovative production processes [29]. Upgrading technology is a priority in emerging economies, as well as collaboration with research and development (R&D) for achieving sustainability [133]. However, sustainable development in business operations is not simple for emerging economies [35]. Intrinsic characteristics become crucial when desires for innovation in any of the supply chain functions are ambitioned.

- ➢

- Barriers to SSCM in emerging economies are characteristic, hence becoming another area of interest in research [25]. Identification of these influential barriers is key to achieving sustainability throughout the supply chain [53]. Mangla, et al. [134] analyzed barriers to achieving sustainable consumption and production practices, and further discussed SSCM as a driver on political and economic transformation from regional, national, and global backgrounds. Economic, social and ecological aspects need to be integrated in institutional barriers and constraints for new SC models in developing countries [122]. Tumpa, et al. [135] determined 15 barriers based on opinions of Bangladesh textile practitioners and SC management divisions and identified the most critical hurdles. There is evidence in developing countries that collaboration amongst stakeholders can improve innovation potential in supply chain operations and remove barriers across its global sustainable practices [27]. For example, the lack of infrastructure and sustainability knowledge can be overcome by cooperation from developed countries [27].

- ➢

- Top management leadership and government support are critical elements in SSCM achievement in emerging economies [136]. Supply chain managers are more interested in sustainability issues due to government regulations [53], and these principles can powerfully influence sustainable supply chain partners’ profit share, achieve a win-win business environment, and become economically feasible [104]. Also, a closer partnership with government and a richer relationship with customers in emerging economies, provides benefits for further technological innovation [27]. Wan Ahmad, Rezaei, Sadaghiani and Tavasszy [96] reported that academic and industry experts have pointed out economic and political stability, and regulatory factors as the most relevant forces in implementing sustainable practices in Brazil. Silvestre [76] even found that regulatory pressure is more significant than market and competitive pressures for businesses in developing countries, and Gold and Schleper [62] argued even contemporary corporate engagement with sustainability is a key barrier when not targeted from a true overall SSC perspective.

5.2. The Research Gaps

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Industrial Sector | References |

|---|---|

| V. Multiple sector | [3,5,7,28,29,40,43,45,73,74,83,86,98,102,103,113,114,115,120,122,125,136] |

| C. Manufacturing | [4,34,35,42,53,68,77,84,85,91,97,99,100,112,119,123,129,130] |

| B. Mining and quarrying | [69,76,90,96] |

| A. Agriculture, forestry and fishing | [47,89,106] |

| Q. Human health and social work activities | [82,128] |

| X. No Specific Sector | [25,71] |

| D. Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | [104] |

| N. Administrative and support service activities | [107] |

| G. Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | [75] |

| E. Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | [105] |

| F. Construction | [101] |

Appendix B

| Methodology | References |

|---|---|

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) | [40,45,73,89,90,103,113,120,125] |

| Data Analysis | [5,69,76,82,104,114,123,130,136] |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) | [4,40,90,113,119] |

| Best-Worst method (BWM) | [96,97,98,115] |

| Content analysis | [25,47,91,105] |

| Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) | [53,84,85] |

| Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) | [29,112,119] |

| Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM) | [35,99,100] |

| MICMAC analysis | [35,99,100] |

| Multiple regression analysis/Regression analysis/ MULTI linear regression analysis | [3,7,74] |

| Statistical Analysis | [43,75,112] |

| Covariance Based Structural Equation Modeling (CB-SEM) | [83,86] |

| Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) | [114,125] |

| Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) | [29,114] |

| Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) | [101,106] |

| Theoretical mathematical modeling | [68,128] |

| Descriptive analysis | [25,101] |

| Cooperative game theory | [77] |

| Data envelopment analysis (DEA) | [42] |

| frequency and contingency analyses | [71] |

| Fuzzy cognitive map (FCM) | [42] |

| Fuzzy-Multi Criteria Decision Making (Fuzzy-MCDM) | [102] |

| Grey Method | [34] |

| Holonic approach analysis | [129] |

| Resource dependence theory (RDT) | [74] |

| SCOR | [122] |

| Value chain analysis | [75] |

References

- Gualandris, J.; Klassen, R.D.; Vachon, S.; Kalchschmidt, M. Sustainable evaluation and verification in supply chains: Aligning and leveraging accountability to stakeholders. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 38, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Garg, D.; Haleem, A. Empirical Analysis of Green Supply Chain Management Practices in Indian Automobile Industry. J. Inst. Eng. Ser. C 2014, 95, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zailani, S.; Jeyaraman, K.; Vengadasan, G.; Premkumar, R. Sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) in Malaysia: A survey. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Silvestre, B.S.; Singh, S. Reactive and proactive pathways to sustainable apparel supply chains: Manufacturer’s perspective on stakeholder salience and organizational learning toward responsible management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Hazen, B.; Dubey, R. Supply chain social sustainability for developing nations: Evidence from India. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 111, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, D.; McCarthy, L.; Heavey, C.; McGrath, P. Environmental and social supply chain management sustainability practices: Construct development and measurement. Prod. Plan. Control. 2015, 26, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.S.; Kaur, R.; Ersöz, F.; Altaf, B.; Basu, A.; Weber, G.-W. Measuring carbon performance for sustainable green supply chain practices: A developing country scenario. Cent. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonelli, F.; Evans, S.; Taticchi, P. Industrial Sustainability: Challenges, perspectives, actions. Int. J. Bus. Innov. Res. 2013, 7, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Washispack, S. Mapping the Path Forward for Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Review of Reviews. J. Bus. Logist. 2018, 39, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, V.; Schoenherr, T.; Charan, P. The thematic landscape of literature in sustainable supply chain management (SSCM): A review of the principal facets in SSCM development. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 1091–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P.; da Silva, C.; Carvalho, A. Opportunities and challenges in sustainable supply chain: An operations research perspective. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 399–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motevali Haghighi, S.; Torabi, S.A.; Ghasemi, R. An integrated approach for performance evaluation in sustainable supply chain networks (with a case study). J. Clean Prod. 2016, 137, 579–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahbodi, A.; Zhang, Y.; Watson, G.; Zhang, T. Governance pressures and performance outcomes of sustainable supply chain management—An empirical analysis of UK manufacturing industry. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 155, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A comparative literature analysis of definitions for green and sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, P.R.C.; Thakkar, J. Sustainable supply chain practices: An empirical investigation on Indian automobile industry. Prod. Plan. Control. 2016, 27, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashmanian, R.M. Building a Sustainable Supply Chain: Key Elements. Environ. Qual. Manag. 2015, 24, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Islam, M.S.; Karia, N.; Fauzi, F.A.; Afrin, S. A literature review on green supply chain management: Trends and future challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.N.; Kant, R. A state-of-art literature review reflecting 15 years of focus on sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 142, 2524–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, L.; Bigliardi, B.; Bottani, E. Sustainable Supply Chain and Innovation: A Review of the Recent Literature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeev, A.; Pati, R.K.; Padhi, S.S.; Govindan, K. Evolution of sustainability in supply chain management: A literature review. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 162, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaram, J.; Avittathur, B. Green supply chains: A perspective from an emerging economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Zuluaga-Cardona, L.; Bailey, A.; Rueda, X. Sustainable supply chain management in developing countries: An analysis of the literature. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 189, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, R.; Mansouri, S.A.; Aktas, E. The relationship between green supply chain management and performance: A meta-analysis of empirical evidences in Asian emerging economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 183, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.K.; Straube, F.; Wutke, S.; Cardoso, P.A. Creating Value by Sustainable Manufacturing and Supply Chain Management Practices—A Cross-Country Comparison. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 8, 686–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Camacho, C.A.; Montoya-Torres, J.R.; Jaegler, A.; Gondran, N. Sustainability metrics for real case applications of the supply chain network design problem: A systematic literature review. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 231, 600–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K. Evaluating challenges to Industry 4.0 initiatives for supply chain sustainability in emerging economies. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 2018, 117, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koberg, E.; Longoni, A. A systematic review of sustainable supply chain management in global supply chains. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 207, 1084–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkis, J. Sustainable and green supply chains: Advancement through Resources, Conservation and Recycling. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, A1–A3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Seuring, S.; Zhu, Q.; Azevedo, S.G. Accelerating the transition towards sustainability dynamics into supply chain relationship management and governance structures. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 112, 1813–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, C.; Tachizawa Elcio, M. Extending sustainability to suppliers: A systematic literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2012, 17, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazancoglu, Y.; Ozkan-Ozen, Y.D.; Ozbiltekin, M. Minimizing losses in milk supply chain with sustainability: An example from an emerging economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Mangla, S.K. When strategies matter: Adoption of sustainable supply chain management practices in an emerging economy’s context. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 138, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Available online: http://www.ask-force.org/web/Sustainability/Brundtland-Our-Common-Future-1987-2008.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. Available online: https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx?hkey=60879588-f65f-4ab5-8c4b-6878815ef921 (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Paulraj, A. Understanding the relationships between internal resources and capabilities, sustainable supply management and organizational sustainability. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2011, 47, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateh, J.; Heaton, C.; Arbogast, G.W.; Broadbent, A. Defining Sustainability in the Business Setting. Am. J. Bus. Educ. 2013, 6, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, K.-C.; Wong, W.P. Pathways for Sustainable Supply Chain Performance—Evidence from a Developing Country, Malaysia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callado, A.; Fensterseifer, J.E. Corporate Sustainability Measure From An Integrated Perspective: The Corporate Sustainability Grid (CSG). Int. J. Bus. Insights Transform. 2011, 3, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S.; Das, M.; Ali, S.M.; Raihan, A.S.; Paul, S.K.; Kabir, G. Evaluating strategies for environmental sustainability in a supply chain of an emerging economy. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 262, 121389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, D.O.C.; Silvestre, B.S. Advancing social sustainability in supply chain management: Lessons from multiple case studies in an emerging economy. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 199, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, T.W. Measuring the Sustainability of Global Supply Chains: Current Practices and Future Directions. J. Glob. Bus. Manag. 2010, 6, 92–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas, S.; Hu, Z.; Wiwattanakornwong, K. Unleashing the role of top management and government support in green supply chain management and sustainable development goals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 8210–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Hahn, R.; Seuring, S. Sustainable supply chain management in “Base of the Pyramid” food projects—A path to triple bottom line approaches for multinationals? Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 784–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, V.F.; Tseng, L.-C. Measuring social compliance performance in the global sustainable supply chain: An AHP approach. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 2014, 35, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reefke, H.; Sundaram, D. Key themes and research opportunities in sustainable supply chain management—Identification and evaluation. Omega 2017, 66, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closs, D.J.; Speier, C.; Meacham, N. Sustainability to support end-to-end value chains: The role of supply chain management. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Bai, E.; Liu, L.; Wei, W. A Framework of Sustainable Service Supply Chain Management: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, D.; Strähle, J.; Müller, M.; Freise, M. Social Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Textile and Apparel Industry—A Literature Review. Sustainability 2017, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Ali, S.M.; Rajesh, R.; Paul, S.K. Modeling the interrelationships among barriers to sustainable supply chain management in leather industry. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 181, 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jeong, B.; Jung, H. Supply chain surplus: Comparing conventional and sustainable supply chains. Flex. Serv. Manuf. J. 2014, 26, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, Z.N.; Qureshi, M.N. Sustainability in Supply Chain Management: An Overview. IUP J. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 12, 24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Beske-Janssen, P.; Johnson, M.P.; Schaltegger, S. 20 years of performance measurement in sustainable supply chain management—What has been achieved? Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 664–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varsei, M. Sustainable supply chain management: A brief literature review. J. Dev. Areas 2016, 50, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J. Sustainable Supply Chain Management Integration: A Qualitative Analysis of the German Manufacturing Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstruck, D.; Teuteberg, F. Understanding the Success Factors of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Empirical Evidence from the Electrics and Electronics Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Shevchenko, A. Why Research in Sustainable Supply Chain Management Should Have no Future. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 50, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taticchi, P.; Tonelli, F.; Pasqualino, R. Performance measurement of sustainable supply chains: A literature review and a research agenda. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2013, 62, 782–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.; Schleper, M.C. A pathway towards true sustainability: A recognition foundation of sustainable supply chain management. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roztocki, N.; Weistroffer, H.R. Information technology success factors and models in developing and emerging economies. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2011, 17, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InvestingAnswers. Emerging Market Economy. Available online: https://investinganswers.com/dictionary/e/emerging-market-economy (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- Fantom, N.; Serajuddin, U. The World Bank’s Classification of Countries by Income. Available online: http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/408581467988942234/pdf/WPS7528.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2020).

- de Abreu, M.C.S.; de Castro, F.; de Assis Soares, F.; da Silva Filho, J.C.L. A comparative understanding of corporate social responsibility of textile firms in Brazil and China. J. Clean Prod. 2012, 20, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S. Socially responsible supply chains in emerging markets: Some research opportunities. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T.-M.; Luo, S. Data quality challenges for sustainable fashion supply chain operations in emerging markets: Roles of blockchain, government sponsors and environment taxes. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 131, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S. Sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies: Environmental turbulence, institutional voids and sustainability trajectories. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 167, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid Raja, U.; Seuring, S.; Beske, P.; Land, A.; Yawar Sadaat, A.; Wagner, R. Putting sustainable supply chain management into base of the pyramid research. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2015, 20, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, R.U.; Seuring, S. Analyzing Base-of-the-Pyramid Research from a (Sustainable) Supply Chain Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 663–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Lai, K.H.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.C.E. Multinational enterprise buyers’ choices for extending corporate social responsibility practices to suppliers in emerging countries: A multi-method study. J. Oper. Manag. 2018, 63, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Lu, J. Empirical Research on Influencing Factors of Sustainable Supply Chain Management—Evidence from Beijing, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahbodi, A.; Zhang, Y.; Watson, G. Sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies: Trade-offs between environmental and cost performance. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Luciano, C.A.; Rondón Domínguez, F.R.; González-Andrés, F.; Urbano López De Meneses, B. Sustainable supply chain management: Contributions of supplies markets. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 184, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S. A hard nut to crack! Implementing supply chain sustainability in an emerging economy. J. Clean Prod. 2015, 96, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian, S.; Hafezalkotob, A.; John, J.J. Sharing economy in organic food supply chains: A pathway to sustainable development. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 218, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, S.M.; Kazemi, N.; Abdul-Rashid, S.H. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Automotive Industry: A Process-Oriented Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United, N. International Standard Industrial Classification of All Industrial Activities (ISIC), Rev.4. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/publication/seriesM/seriesm_4rev4e.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Gao, D.; Xu, Z.; Ruan, Y.Z.; Lu, H. From a systematic literature review to integrated definition for sustainable supply chain innovation (SSCI). J. Clean Prod. 2017, 142, 1518–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, M.; Hahn, G.J.; Rebs, T. Sustainable Supply Chains: Recent Developments and Future Trends. In Social and Environmental Dimensions of Organizations and Supply Chains; Brandenburg, M., Hahn, G.J., Rebs, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scavarda, A.; Daú, G.L.; Scavarda, L.F.; Korzenowski, A.L. A proposed healthcare supply chain management framework in the emerging economies with the sustainable lenses: The theory, the practice, and the policy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Mani, K.T.N. Supply chain social sustainability in small and medium manufacturing enterprises and firms’ performance: Empirical evidence from an emerging Asian economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 227, 107656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Application of DEMATEL approach to identify the influential indicators towards sustainable supply chain adoption in the auto components manufacturing sector. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 172, 2931–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathivathanan, D.; Kannan, D.; Haq, A.N. Sustainable supply chain management practices in Indian automotive industry: A multi-stakeholder view. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A.; Delgado, C. Enhancing supply chain performance through supplier social sustainability: An emerging economy perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 195, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastas, A.; Liyanage, K. Sustainable supply chain quality management: A systematic review. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 181, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöggl, J.-P.; Fritz, M.M.C.; Baumgartner, R.J. Toward supply chain-wide sustainability assessment: A conceptual framework and an aggregation method to assess supply chain performance. J. Clean Prod. 2016, 131, 822–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, P.; Tse, Y.K.; Khan, Z.; Rao-Nicholson, R. Data-driven and adaptive leadership contributing to sustainability: Global agri-food supply chains connected with emerging markets. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bag, S.; Wood, L.C.; Xu, L.; Dhamija, P.; Kayikci, Y. Big data analytics as an operational excellence approach to enhance sustainable supply chain performance. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 153, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vargas Mores, G.; Finocchio, C.P.S.; Barichello, R.; Pedrozo, E.A. Sustainability and innovation in the Brazilian supply chain of green plastic. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 177, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D.; Altuntas, C. Sustainable supply chain management in the fast fashion industry: An analysis of corporate reports. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Kasturiratne, D.; Moizer, J. A hub-and-spoke model for multi-dimensional integration of green marketing and sustainable supply chain management. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2012, 41, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, A.-M.; Davies, B. Sustainable supply chains—Minerals and sustainable development, going beyond the mine. Resour. Policy 2012, 37, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morali, O.; Searcy, C. A Review of Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices in Canada. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 117, 635–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan Ahmad, W.N.K.; Rezaei, J.; Sadaghiani, S.; Tavasszy, L.A. Evaluation of the external forces affecting the sustainability of oil and gas supply chain using Best Worst Method. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 153, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munny, A.A.; Ali, S.M.; Kabir, G.; Moktadir, M.A.; Rahman, T.; Mahtab, Z. Enablers of social sustainability in the supply chain: An example of footwear industry from an emerging economy. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhi, S.A.; Enayet, R.; Haque, T.; Ali, S.M.; Moktadir, M.A.; Paul, S.K. Environmental sustainability assessment in supply chain: An emerging economy context. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 79, 106306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Kannan, D.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Analysis of enablers for implementation of sustainable supply chain management—A textile case. J. Clean Prod. 2014, 83, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, V. Impediments to Social Sustainability Adoption in the Supply Chain: An ISM and MICMAC Analysis in Indian Manufacturing Industries. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2016, 17, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki, P.F.; Abduh, M.; Driejana, R. The Sustainable Infrastructure through the Construction Supply Chain Carbon Footprint Approach. Procedia Eng. 2017, 171, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S.S.; Pati, R.K.; Rajeev, A. Framework for selecting sustainable supply chain processes and industries using an integrated approach. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 184, 969–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, S.K.; Rathore, H.; Mangla, S.K. Is lean synergistic with sustainable supply chain? An empirical investigation from emerging economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Huang, H.; Tang, O. Sustainable supply chain collaboration with outsourcing pollutant-reduction service in power industry. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 186, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, B.D.; Scavarda, L.F.; Caiado, R.G.G. Urban solid waste management in developing countries from the sustainable supply chain management perspective: A case study of Brazil’s largest slum. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 233, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R.; Agarwal, R.; Bajada, C.; Arshinder, K. Redesigning a food supply chain for environmental sustainability—An analysis of resource use and recovery. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 242, 118374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmonico, D.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Pereira, S.C.F.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Thomé, A.M.T. Unveiling barriers to sustainable public procurement in emerging economies: Evidence from a leading sustainable supply chain initiative in Latin America. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhao, Q.; An, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Q. Pricing strategy of environmental sustainable supply chain with internalizing externalities. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 170 Pt B, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shah, N.; Wassick, J.; Helling, R.; van Egerschot, P. Sustainable supply chain optimisation: An industrial case study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 74, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, L. Assessing the economic performance of an environmental sustainable supply chain in reducing environmental externalities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 255, 463–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Zhao, Q.; An, Z.; Tang, O. Collaborative mechanism of a sustainable supply chain with environmental constraints and carbon caps. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181 Pt A, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Moktadir, A.; Liman, Z.R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Hegemann, K.; Rehman Khan, S.A. Evaluating sustainable drivers for social responsibility in the context of ready-made garments supply chain. J. Clean Prod. 2020, 248, 119231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón Vargas, J.R.; Moreno Mantilla, C.E.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L. Enablers of sustainable supply chain management and its effect on competitive advantage in the Colombian context. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Agarwal, R.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Dubey, R.; Childe, S.J. Social sustainability in the supply chain: Construct development and measurement validation. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 71, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri Ahmadi, H.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Rezaei, J. Assessing the social sustainability of supply chains using Best Worst Method. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawar, S.A.; Seuring, S. Management of Social Issues in Supply Chains: A Literature Review Exploring Social Issues, Actions and Performance Outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 141, 621–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajbakhsh, A.; Hassini, E. A data envelopment analysis approach to evaluate sustainability in supply chain networks. J. Clean Prod. 2015, 105, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, P.; Seuring, S. Putting sustainability into supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 19, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, R.; Meena, P.L.; Barua, M.K.; Tibrewala, R.; Kumar, G. Impact of sustainability and manufacturing practices on supply chain performance: Findings from an emerging economy. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, M. Sustainable supply chain management practices, supply chain dynamic capabilities, and enterprise performance. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 172, 3508–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardine-Baumann, E.; Botta-Genoulaz, V. A framework for sustainable performance assessment of supply chain management practices. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 76, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendul, J.C.; Rosca, E.; Pivovarova, D. Sustainable supply chain models for base of the pyramid. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 162, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Akbari, M.; Maleki Far, S. Recent sustainable trends in Vietnam’s fashion supply chain. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 225, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Cheng, T.C.E. Sustainable supply chain management: Advances in operations research perspective. Comput. Oper. Res. 2015, 54, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A. Four forces of supply chain social sustainability adoption in emerging economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 199, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, H.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Zhou, Z. Institutional pressures, sustainable supply chain management, and circular economy capability: Empirical evidence from Chinese eco-industrial park firms. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 155, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulraj, A.; Chen, I.J.; Blome, C. Motives and Performance Outcomes of Sustainable Supply Chain Management Practices: A Multi-theoretical Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, L.; Alexiou, C.; Nellis J, J.G.; Steele, P.; Tolani, F. Developing a sustainability index for public health supply chains. Sustain. Futures 2020, 2, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Gómez, A.; Aguayo-González, F.; Luque, A. A holonic framework for managing the sustainable supply chain in emerging economies with smart connected metabolism. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, B.S.; Monteiro, M.S.; Viana, F.L.E.; de Sousa-Filho, J.M. Challenges for sustainable supply chain management: When stakeholder collaboration becomes conducive to corruption. J. Clean Prod. 2018, 194, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, A.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jabbour, A.B.L.d.S. Managing organizations for sustainable development in emerging countries: An introduction. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.M.; Gomes, P.J.; Sarkis, J. The role of innovation in the implementation of green supply chain management practices. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 819–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Kumar, P.; Barua, M.K. Prioritizing the responses to manage risks in green supply chain: An Indian plastic manufacturer perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 1, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, S.K.; Govindan, K.; Luthra, S. Prioritizing the barriers to achieve sustainable consumption and production trends in supply chains using fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process. J. Clean Prod. 2017, 151, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumpa, T.J.; Ali, S.M.; Rahman, M.H.; Paul, S.K.; Chowdhury, P.; Rehman Khan, S.A. Barriers to green supply chain management: An emerging economy context. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 236, 117617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Gong, Y.; Brown, S. Multi-tier sustainable supply chain management: The role of supply chain leadership. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 217, 44–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.; Lim, M.; Wong, W.P. Sustainable supply chain management: A closed-loop network hierarchical approach. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 436–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Area of Search | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Title | Supply chain, sustainability, sustainable |

| 2 | Title, Abstract, Keywords | Developing country, developing countries, developing nation, developing nations, developing economy, developing economies, developing market, developing markets, emerging country, emerging countries, emerging economy, emerging economies, emerging market, emerging markets |

| Step | Area of Search | Search String | Articles Output (qty) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Title | (Supply chain AND Sustainab*) | 780 |

| 2 | Title, Abstract, Keywords | (Developing countr* OR developing nation* OR developing econom* OR developing market* OR emerging countr* OR emerging econom* OR emerging market*) | 67 |

| Research Methodology | Total |

|---|---|

| Empirical Model/Analysis | 35 |

| Case Study | 12 |

| Methodological, Analytical, Mathematical | 6 |

| Systematic literature review | 3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Flores, R.B.; Cruz-Sotelo, S.E.; Ojeda-Benitez, S.; Ramírez-Barreto, M.E. Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176972

Sánchez-Flores RB, Cruz-Sotelo SE, Ojeda-Benitez S, Ramírez-Barreto ME. Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176972

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Flores, Rebeca B., Samantha E. Cruz-Sotelo, Sara Ojeda-Benitez, and Ma. Elizabeth Ramírez-Barreto. 2020. "Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176972

APA StyleSánchez-Flores, R. B., Cruz-Sotelo, S. E., Ojeda-Benitez, S., & Ramírez-Barreto, M. E. (2020). Sustainable Supply Chain Management—A Literature Review on Emerging Economies. Sustainability, 12(17), 6972. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176972