Modelling Municipal Social Responsibility: A Pilot Study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain)

Abstract

1. Introduction

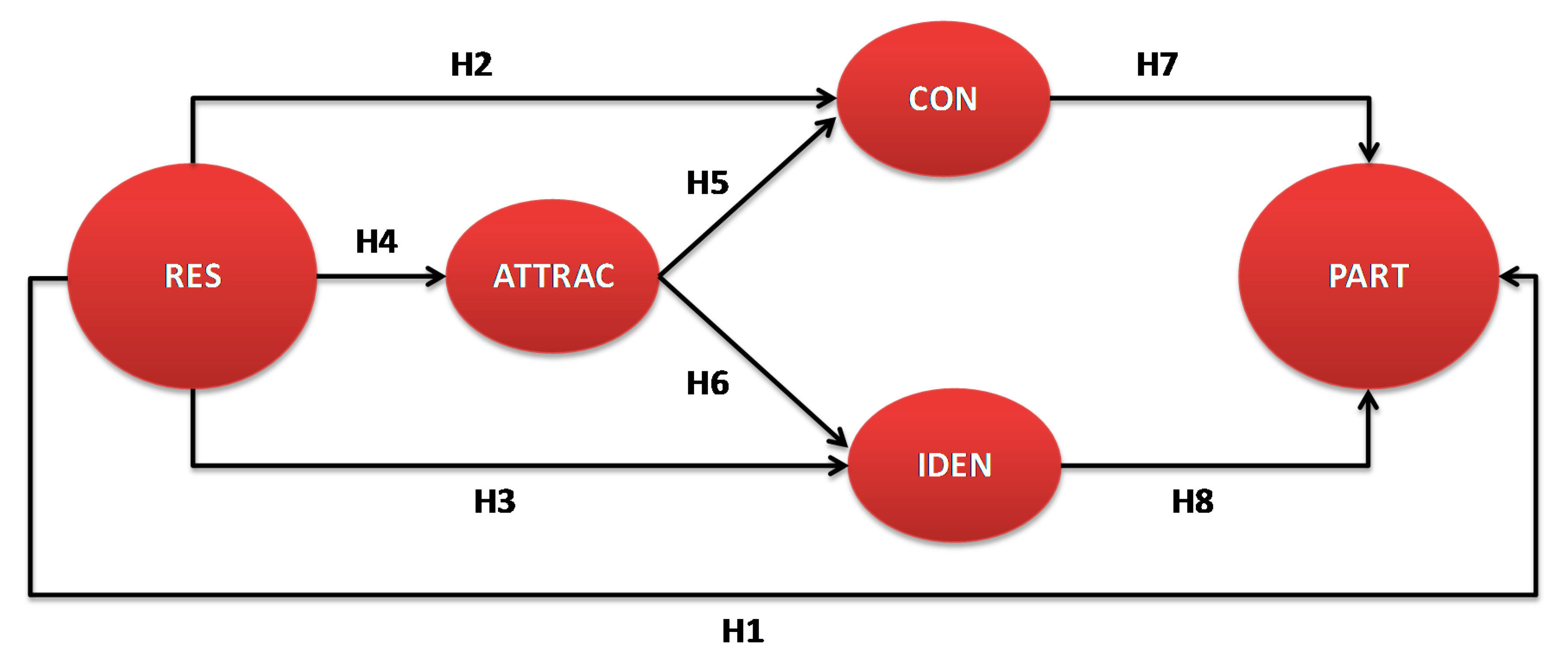

2. Theoretical Foundations and Hypotheses Development

2.1. From SR to Sustainable Development

2.2. Theoretical Framework for Public Administration Today

2.3. The Expected Effect of Municipal Social Responsibility on Citizens

3. Method

3.1. Sample, Instrument and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation

- Indicator acceptance [81,97,98]—The factor loadings obtained satisfied the strictest criterion (λ > 0.7). We want to highlight that it was unnecessary removing items from the initial model because all of the original items meet the strictest criterion of individual reliability. The minimum factor loading obtained was 0.827 for the first item of the participation construct.

- Internal consistency of the constructs of the measurement model—Using Cronbach´s Alfa coefficient, internal consistency for each element into the model was estimated as a high 0.98 for the municipality orientation to SR, 0.93 for the attractiveness construct, 0.89 for the personal connection construct, 0.94 for citizen´s identification, and 0.89 for citizen´s participation. All the composite reliability indicators were above the 0.7 threshold recommended by Nunnally [99].

- Properties of the measurement model—Convergent validity was confirmed. The average variance extracted (AVE) was always above 0.50, indicative that more variance was explained than unexplained in the variables associated with a given construct [100]. The model shows very good values for the AVE (0.77 for RES; 0.83 for ATTRAC; 0.74 for CON; 0.80 for IDEN; 0.74 for PART).

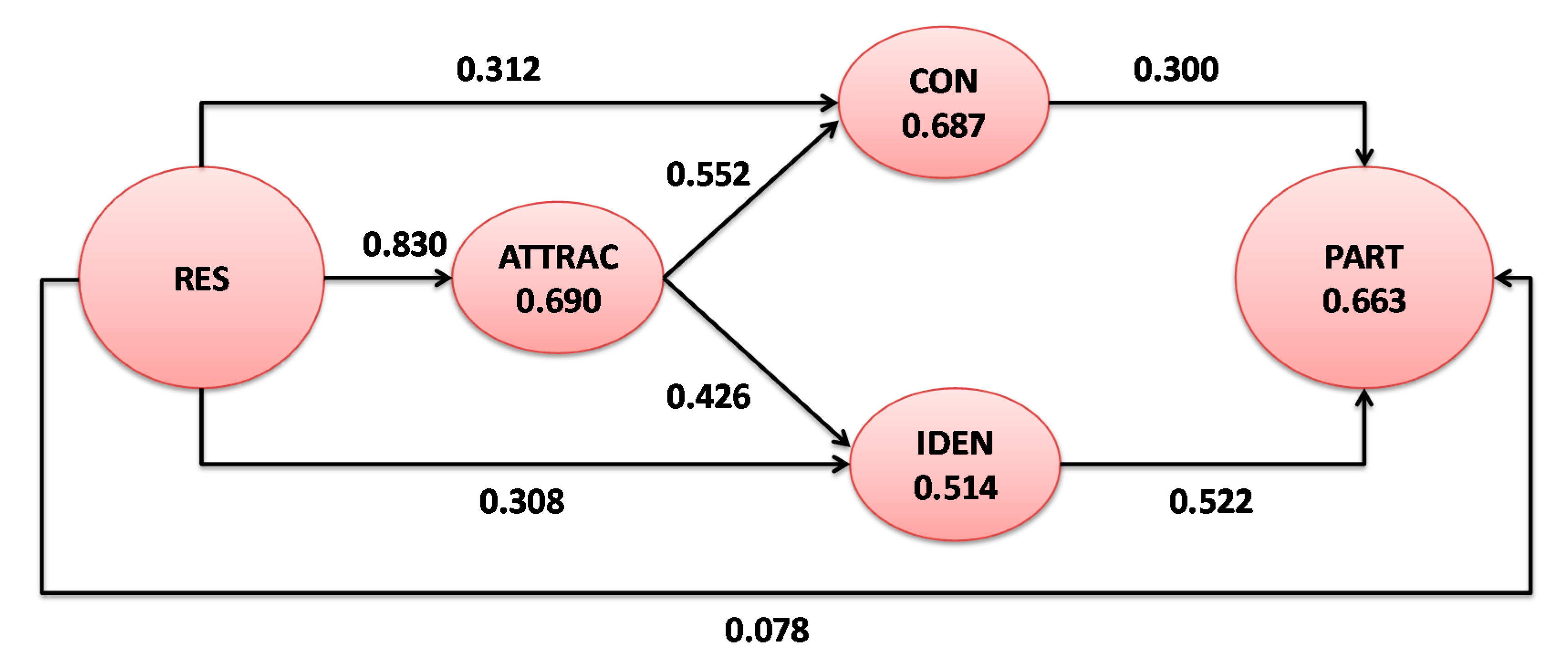

4.2. The Structural Model Interpretation

- The goodness of a model—It is determined by the strength of each structural path and analysed using the value of R2 (explained variance) for the dependent latent variables. Figure 2 shows the main results and high predictive power of the model. R2 for each dependent variable is graphically shown in the figure in the middle of the construct with the high values of 0.69, 0.68, 0.51 and 0.66 respectively for ATTRAC, CON, IDEN and PART.

- The Stone–Geisser test—It is used to verify the predictive relevance of the model (Q2 > 0) [98]. In the model, all Q2 are positive demonstrating its predictive relevance. In other words, the observed values are well reconstructed by the model.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Shiller, R.J. The Subprime Solution: How Today’s Global Financial Crisis Happened, and What to Do about It; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, M.G.; Jiménez-Sánchez, F.; Villoria, M. Building Local Integrity Systems in Southern Europe: The case of urban local corruption in Spain. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2013, 79, 618–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, B.; Guillamón, M.D.; Bastida, F. Determinants of urban political corruption in local governments. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2015, 63, 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrado, S.; Dahlström, C.; Lapuente, V. Mayors and Corruption in Spain: Same Rules, Different Outcomes. South Eur. Soc. Politics 2018, 23, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drápalová, E.; Di Mascio, F. Islands of good government: Explaining successful corruption control in two Spanish cities. Politics Gov. 2020, 8, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, L. Anti-corruption agencies: Between empowerment and irrelevance. Crime Law Soc. Chang. 2010, 53, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungiu-Pippidi, A.; Johnston, M. (Eds.) Transitions to Good Governance: Creating Virtuous Circles of Anti-Corruption; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Michael, B.; Mendes, S. Anti-corruption law in local government. Int. J. Law Manag. 2012, 54, 26–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Choi, S.O.; Kim, J.; Jung, M. A Study on the Factors Affecting Decrease in the Government Corruption and Mediating Effects of the Development of ICT and E-Government—A Cross-Country Analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cini, M. European Commission reform and the origins of the European Transparency Initiative. J. Eur. Public Policy 2008, 15, 743–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Rodríguez, D.; Navarro-Galera, A.; Alcaraz-Quiles, F.J. The influence of administrative culture on sustainability transparency in European local governments. Adm. Soc. 2018, 50, 555–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Buchholtz, A. Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management, 8th ed.; South-Western Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hakovirta, M.; Denuwara, N. How COVID-19 redefines the concept of sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R. Making Sustainability Work: Best Practices in Managing and Measuring Corporate Social, Environmental, and Economic Impacts; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Gertner, D. Country as brand, product, and beyond: A place marketing and brand management perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, J.; Braun, E.; Klijn, E.H. Place marketing as governance strategy: An assessment of obstacles in place marketing and their effects on attracting target groups. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleave, E.; Arku, G.; Sadler, R.; Kyeremeh, E. Place marketing, place branding, and social media: Perspectives of municipal practitioners. Growth Chang. 2017, 48, 1012–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanová, A.; Boxiková, A.; Foret, M. Communicating Town. In Best Practices in Marketing and Their Impact on Quality of Life; Alves, H., Vázquez, J.L., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgon, J. New directions in public administration: Serving beyond the predictable. Public Policy Adm. 2009, 24, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminia, M. Bienstock, C.C. Corporate sustainability: An integrative definition and framework to evaluate corporate practice and guide academic research. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. Measuring Corporate Social Responsibility for competitive success at a regional level. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Value: The Role of Customer Awareness. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogl, C.; Holtbrugge, D. Corporate environmental responsibility, employer reputation and employee commitment: An empirical study in developed and emerging economies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1739–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girerd, I.; Jimenez, S.; Louvet, P. Which Dimensions of Social Responsibility Concern Financial Investors? J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 559–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narmania, D. Efficient Management of Municipal Enterprises. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2018, 3, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrevova, L.; Jelinkova, M. Municipal Social Responsibility of Statutory Cities in the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakitovac, K.A.; Bencic, M.T. Municipal Social Responsibility. In Economic and Social Development: Book of Proceedings, Proceedings of the 51st International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Rabat, Morocco, 26–27 March 2020; Hammes, K., Machrafi, M., Huzjan, V., Eds.; Varazdin Development and Entrepreneurship Agency: Varazdin, Croatia, 2020; pp. 528–538. [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi, M.; Magnan, G.M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Understanding the conceptual evolutionary path and theoretical underpinnings of corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.S.; Carroll, A.B. Integrating and unifying competing and complementary frameworks: The search for a common core in the business and society field. Bus. Soc. 2008, 47, 148–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I. Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability: Separate pasts, common futures. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). The Bruntland Report: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future; United Nations General Assembly Document A/42/427; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1987.

- Klopp, J.M.; Petretta, D.L. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities 2017, 63, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinkernagel, R.; Evans, J.; Neij, L. Applying the SDGs to cities: Business as usual or a new Dawn? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, P.; van Lindert, P. Sustainable housing and the urban poor. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2016, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soederberg, S. Universal access to affordable housing? Interrogating an elusive development goal. Globalizations 2017, 14, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, P.; Floater, G.; Thomopoulos, N.; Docherty, J.; Schwinger, P.; Mahendra, A.; Fang, W. Accessibility in cities: Transport and urban form. In Disrupting Mobility; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 239–273. [Google Scholar]

- Buehler, R.; Pucher, J. Making public transport financially sustainable. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, J.; Wretstrand, A.; Schmidt, S.M. Exploring public transport as an element of older persons’ mobility: A Capability Approach perspective. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 48, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, D.; Bernet, J.S. Public transport and accessibility in informal settlements: Aerial cable cars in Medellín, Colombia. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 4, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Joss, S.; Schraven, D.; Zhan, C.; Weijnen, M. Sustainable–smart–resilient–low carbon–eco–knowledge cities; making sense of a multitude of concepts promoting sustainable urbanization. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allam, Z.; Newman, P. Redefining the smart city: Culture, metabolism and governance. Smart Cities 2018, 1, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, P.; Pereira Roders, A.R.; Colenbrander, B. Impacts of common urban development factors on cultural conservation in world heritage cities: An indicators-based analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, D.L.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Grove, J.M.; Marshall, V.; McGrath, B.; Pickett, S.T. An ecology for cities: A transformational nexus of design and ecology to advance climate change resilience and urban sustainability. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3774–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.; Ebi, K.L.; Forsberg, B. Factors increasing vulnerability to health effects before, during and after floods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 7015–7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeliger, L.; Turok, I. Towards sustainable cities: Extending resilience with insights from vulnerability and transition theory. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2108–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J. Innovation in governance and public services: Past and present. Public Money Manag. 2005, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A. Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B.S. Review essay: Citizenship and political globalization. Citizsh. Stud. 2000, 4, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkers, V.; Edelenbos, J.; Steijn, B. (Eds.) Innovation in the Public Sector; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, J. Improving public service delivery: The crossroads between NPM and traditional bureaucracy. Public Adm. 2001, 79, 915–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaredo, D.D.; Álvarez, J.F.Á. Social Networks and University Spaces. Knowledge and Open Innovation in the Ibero-American Knowledge Space. RUSC Univ. Knowl. Soc. J. 2012, 9, 245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Bourgon, J. Responsive, responsible and respected government: Towards a New Public Administration theory. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2007, 73, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, J. Multi-level citizenship, identity and regions in contemporary Europe. In Transnational Democracy: Political Spaces and Border Crossings; Anderson, J., Ed.; Roudledge: London, UK, 2002; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Le Grand, J. The Other Invisible Hand: Delivering Public Services through Choice and Competition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wan Wart, M. When public participation in administration leads to trust: An empirical assessment of managers’ perceptions. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. From responsiveness to collaboration: Governance, citizens, and the next generation of public administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2002, 62, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo-Campo, S. Performance in the public sector. Asian J. Political Sci. 1999, 7, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigoda, E. Collaborative public administration: Some lessons from the Israeli experience. Manag. Audit. J. 2004, 19, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Marshfield, WI, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berner, M.M.; Amos, J.M.; Morse, R.S. What constitutes effective citizen participation in local government? Views from city stakeholders. Public Adm. Q. 2011, 35, 128–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ndaguba, E.A.; Hanyane, B. Stakeholder model for community economic development in alleviating poverty in municipalities in South Africa. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummesson, E. Total Relationship Marketing; Butterworth-Hinemann: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gremler, D.D.; Gwinner, K.P. Customer-employee rapport in service relationships. J. Serv. Res. 2000, 3, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Jenkins, B. From public administration to public management: Reassessing a revolution? Public Adm. 1995, 73, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Public Trust in Government in Japan and South Korea: Does the Rise of Critical Citizens Matter? Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servillo, L.; Atkinson, R.; Russo, A.P. Territorial attractiveness in EU urban and spatial policy: A critical review and future research agenda. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2012, 19, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyadin, S.; Streltsova, E.; Borodin, A.; Kiseleva, N.; Yakovenko, I.; Baimukhanbetova, E. Assessment of investment attractiveness of projects on the basis of environmental factors. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, G.T.; Lee, S.H. Consumers’ trust in a brand and the link to brand loyalty. J. Mark. Focused Manag. 1999, 4, 341–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounaris, S.; Stathakopoulos, V. Antecedents and consequences of brand loyalty: An empirical study. J. Brand Manag. 2004, 11, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hal, R.G. Understanding and Managing Public Organizations, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D.W. Editor’s Comments: A Critical Look at the Use of PLS-SEM in” MIS Quarterly”. MIS Q. 2012, 36, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Will, S. SmartPLS 2.0 (M3) Beta. Hamburg. 2005. Available online: www.smartpls.de (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Barclay, D.; Thompson, R.; Higgins, C. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal Modeling: Personal Computer Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–309. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Canyelles, J.M. Responsabilidad social de las administraciones públicas. Rev. Contab. Dir. 2011, 13, 77–104. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, E. Integrity, Transparency and Accountability in Public Administration: Recent Trends, Regional and International Developments and Emerging Issues; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, A.; Doig, A. Researching ethics for public service organizations: The view from Europe. Public Integr. 2006, 8, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.S.; Halligan, J.; Cho, N.; Oh, C.H.; Eikenberry, A.M. Toward Participatory and Transparent Governance: Report on the Sixth Global Forum on Reinventing Government. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cruz, N.F.; Tavares, A.F.; Marques, R.C.; Jorge, S.; De Sousa, L. Measuring local government transparency. Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 866–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galera, A.N.; de los Ríos Berjillos, A.; Lozano, M.R.; Valencia, P.T. Transparency of sustainability information in local governments: English-speaking and Nordic cross-country analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 64, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevado-Gil, T.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Sánchez-Hernández, M.I. La Administración Local y su implicación en la creación de una cultura socialmente responsable: Información divulgada en la Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura. Prism. Soc. Rev. Cienc. Soc. 2013, 10, 64–118. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Ramos Vidal, I. Detecting key actors in interorganizational networks. Cuad. Gest. 2017, 17, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Castro, D.; De Elizagarate Gutierrez, V.; Kazak, J.; Szewranski, S.; Kaczmarek, I.; Wang, T. Nuevos desafíos para el perfeccionamiento de los procesos de participación ciudadana en la gestión urbana. Retos para la innovación social. Cuad. Gestión 2020, 20, 41–64. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.D.; Lacy, D.P.; Dougherty, M.J. Improving performance and accountability in local government with citizen participation. Innov. J. Public Sect. Innov. J. 2005, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, F.; Tops, P. Between democracy and efficiency: Trends in local government reform in the Netherlands and Germany. Public Adm. 1999, 77, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Towards the suitable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.H.; Seo, J.H.; Yoon, T.S. Effects of contact employee supports on critical employee responses and customer service evaluation. J. Serv. Mark. 2004, 18, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmines, E.G.; Zeller, R.A. Reliability and validity assessment. In Sage University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. N-07-017; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W. Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modelling. MIS Q. 1998, 2, vii–xv. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Phychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modelling; The University of Arkon: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Geographical Scope | 3 Municipalities in Extremadura (Region in Spain) |

| Universe | 13,284 citizens |

| Method of Information Collection | Personal contact |

| Sample | 256 (133 men; 123 women) |

| Measurement Error | 6% |

| Trust Level | 95% z = 1.96 p = q = 0.5 |

| Sampling Method | Simple random |

| Average Duration of the Interview | 10 min |

| Hypothesis: A → B | Original Path Coefficient (β) | Mean of Sub-Sample Path Coefficient | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: RES→ PART | 0.660 | 0.660 | 12.13 *** |

| H2: RES → CON | 0.769 | 0.768 | 20.66 *** |

| H3: RES → IDEN | 0.676 | 0.674 | 15.33 *** |

| H4: RES → ATTRAC | 0.830 | 0.829 | 36.61 *** |

| H5: ATTRAC → CON | 0.551 | 0.553 | 6.80 *** |

| H6: ATTRAC→IDEN | 0.426 | 0.422 | 4.91 *** |

| H7: CON →PART | 0.300 | 0.295 | 3.48 *** |

| H8: IDEN →PART | 0.522 | 0.521 | 8.44 *** |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Hernández, M.I.; Aguilar-Yuste, M.; Maldonado-Briegas, J.J.; Seco-González, J.; Barriuso-Iglesias, C.; Galán-Ladero, M.M. Modelling Municipal Social Responsibility: A Pilot Study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2020, 12, 6887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176887

Sánchez-Hernández MI, Aguilar-Yuste M, Maldonado-Briegas JJ, Seco-González J, Barriuso-Iglesias C, Galán-Ladero MM. Modelling Municipal Social Responsibility: A Pilot Study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176887

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Hernández, Maria Isabel, Manuel Aguilar-Yuste, Juan José Maldonado-Briegas, Jesús Seco-González, Cristina Barriuso-Iglesias, and Maria Mercedes Galán-Ladero. 2020. "Modelling Municipal Social Responsibility: A Pilot Study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain)" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176887

APA StyleSánchez-Hernández, M. I., Aguilar-Yuste, M., Maldonado-Briegas, J. J., Seco-González, J., Barriuso-Iglesias, C., & Galán-Ladero, M. M. (2020). Modelling Municipal Social Responsibility: A Pilot Study in the Region of Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability, 12(17), 6887. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176887