Resources Confirmation for Tourism Destinations Marketing Efforts Using PLS-MGA: The Moderating Impact of Semirural and Rural Tourism Destination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stakeholder Theory and Rural Tourism Destination Marketing Efforts

2.2. Rural Tourism Destination Marketing Efforts

2.3. Hard and Soft Components of Rural Tourism

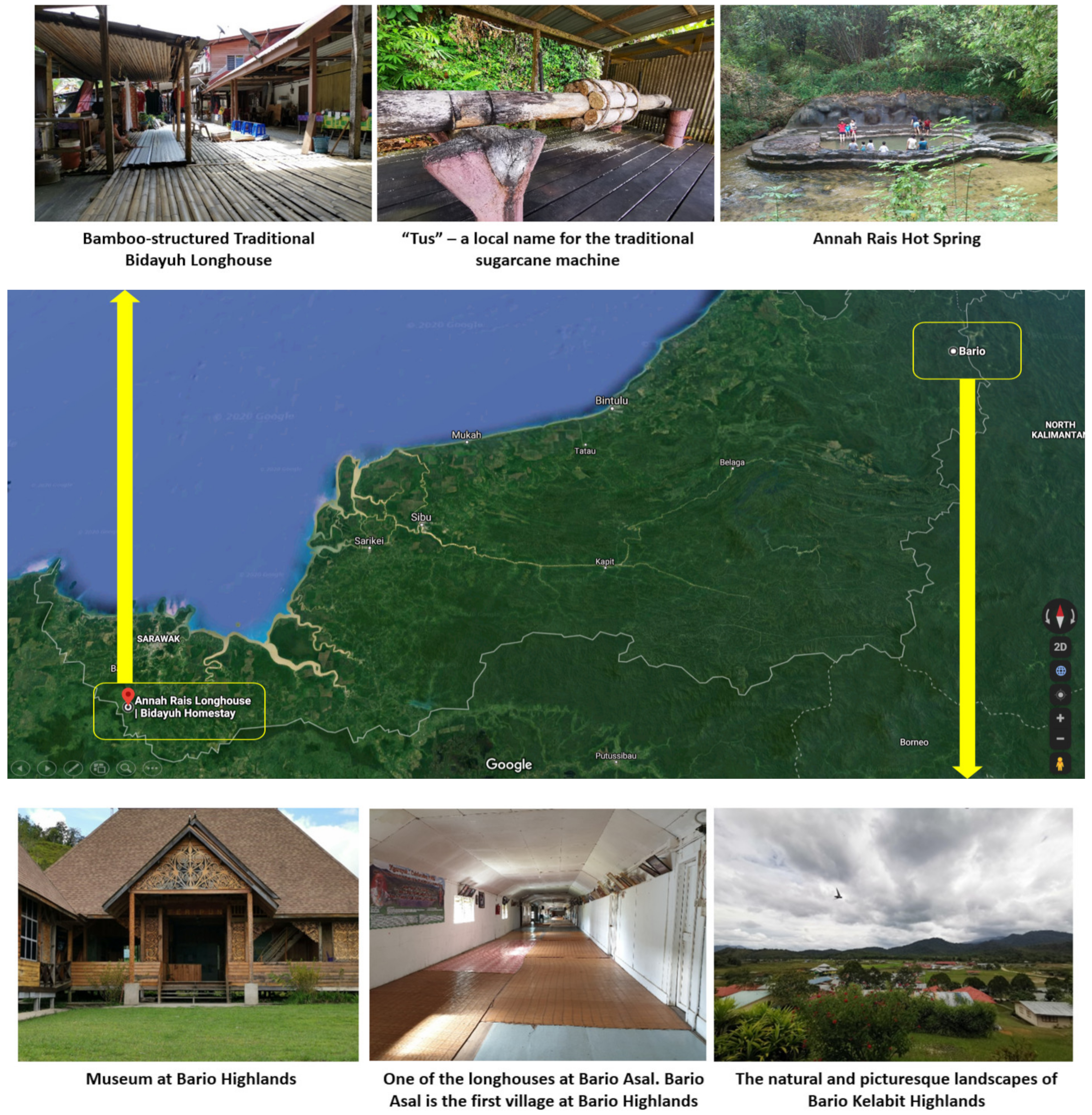

2.4. Semirural and Rural Tourism Destination

2.5. Hypotheses Development

2.5.1. Hard and Soft Components on Rural Tourism Destination Marketing Efforts

2.5.2. The Nature of Tourism Destination (Semirural and Rural)

3. Methodology

4. Findings

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.2. Assessment of the Measurement Invariance

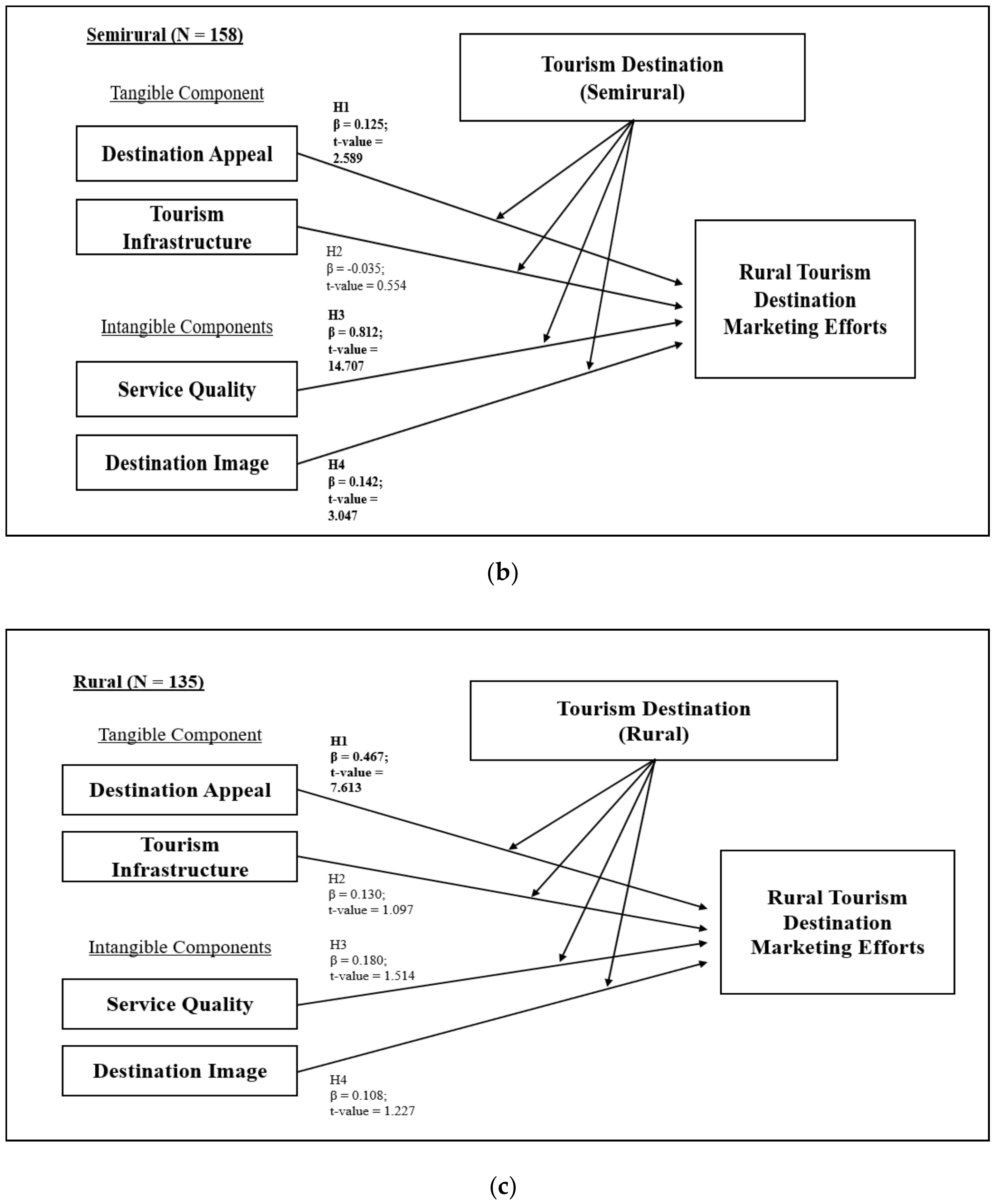

4.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

4.4. Assessment of Group Differences

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Implications

6.2. Limitations of the Research

6.3. Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct(s) | Item(s) | Measurement Item(s) | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Destination Appeal (DA) | DA_01 | This place has beautiful flora and fauna. | [111,113] |

| DA_02 | This place has attractive natural scenery. | ||

| DA_03 | This place is rich with natural resources. | ||

| DA_04 | This place has variety of unique cultural attractions. | ||

| DA_05 | This place has unique heritage attractions. | ||

| DA_06 | This place has high quality craft products. | ||

| DA_07 | This place has many outdoor adventurous activities. | ||

| Tourism Infrastructure (TI) | TI_01 | This place has adequacy of infrastructure to meet visitor needs. | [93,111] |

| TI_02 | This place has availability of local transport systems to support tourism facilities. | ||

| TI_03 | The accommodation in this place has good quality. | ||

| TI_04 | There are electricity supplies in this place. | ||

| TI_05 | This place has the availability of telecommunication system for tourists. | ||

| TI_06 | The tourist attract spot are easily accessible. | ||

| Service Quality (SQ) | SQ_01 | The service providers were friendly and courteous. | [66] |

| SQ_02 | The service providers provided prompt service. | ||

| SQ_03 | The service providers were knowledgeable about the products and services offered. | ||

| SQ_04 | The service providers were professional and gave me confidence. | ||

| SQ_05 | The service providers were always willing to help me. | ||

| Destination Image (DI) | DI_01 | This place is safe and clean. | [76] |

| DI_02 | This place is a restful and relaxing place to visit. | ||

| DI_03 | There are many places of interest to visit in this place. | ||

| DI_04 | This place offers a pleasant environment. | ||

| DI_05 | This place provides an exciting experience. | ||

| DI_06 | This place provides a relaxing environment. | ||

| Destination Marketing Efforts (DM) | DM_01 | Tourism helps to increase the development of a strong destination image. | [111] |

| DM_02 | This place has an overall favorable image in the world community. | ||

| DM_03 | This place has commitment to providing a satisfactory vacation experience for tourists. | ||

| DM_04 | This place has continuous commitment to the ongoing improvement and development of a high-quality destination. | ||

| DM_05 | This place has commitment to providing a safe and secure environment. |

References

- Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Gössling, S. Global tourism vulnerability to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ishtiaq, M.; Thanh, B.T. Tourism industry and economic growth nexus in Beijing, China. Economies 2019, 7, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- UNWTO. International Tourist Numbers Could Fall 60–80% in 2020, UNWTO Reports. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/covid-19-international-tourist-numbers-could-fall-60-80-in-2020 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Er, A.C.; Simon, S. Marketing mix of ecotourism product in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, R. Measuring tourism methods, indicators, and needs: Innovation and sustainability. In The Future of Tourism: Innovation and Sustainability; Fayos-Sola, E., Cooper, C., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 255–269. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes. Why Millennials Are the Most Important Consumer Generation for the Travel Industry. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jefffromm/2017/11/08/why-millennials-are-the-most-important-consumer-generation-for-the-travel%20industry/#5725b740e1f1 (accessed on 18 December 2019).

- Ibănescu, B.-C.; Stoleriu, O.M.; Munteanu, A.; Iaţu, C. The Impact of Tourism on Sustainable Development of Rural Areas: Evidence from Romania. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edirin, E.A. Opportunities and challenges of economic development in Malaysia’s rural areas. Trends Undergrad. Res. 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maksin, M. Sustainable heritage utilization in rural tourism development in Serbia. Spatium Int. Rev. 2012, 28, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Five challenges to stakeholder theory: A report on research in progress. In Business and Society 360 Stakeholder Management; Wasieleski, D.M., Weber, J., Eds.; Emerald Group: Bingley, UK, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe, D.F.; Ortiz-Marcos, I.; Uruburu, A. What is going on with stakeholder theory in Project management literature? A symbiotic relationship for sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, T.B.; Magdalena, G.T.; Cornelia, H. The competitiveness of the Uruguayan rural tourism sector and its potential to attract German tourists. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2016, 26, 166–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pjetrotić, L.; Rađenović, M.; Tripković-Marković, A. Stakeholder collaboration in tourism destination planning—The case of Montenegro. Economics 2016, 4, 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, C.; Ladkin, A.; Fletcher, J. Stakeholder collaborations and heritage management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management, 2nd ed.; CAB International: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, C.H.; Thian, S.S.Z.; Lo, M.C. Community’s experiential knowledge on the development of rural tourism competitive advantage: A study on Kampung Semadang—Borneo Heights, Sarawak. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 238–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, M.A. Tourism Destination Competitiveness: A Supply and Demand Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leiper, N. Tourism Management; Pearson Education: Sydney, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, E.J.; Draper, D. A collaborative approach to understanding local stakeholder perceptions of tourism in Churchill, Manitoba (Canada). Polar Geogr. 2007, 30, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcheh, S.A.; Mohamed, B. Local perception of tourism development: A conceptual framework for the sustainable cultural tourism. J. Manag. Sustain. 2013, 3, 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Semrad, K.J.; Rivera, M. A destination performance analysis through the comparisons of tourists and stakeholders’ perceptions: The case of Curaçao. Tour. Hosp. 2015, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Giray, F.H.; Kadakoğlu, B.; Çetin, F.; Bamoi, A.G.A. Rural tourism marketing: Lavender tourism in Turkey. Ciência Rural. 2019, 49, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, F.; Birgit, P. Destination image analysis—A cross-cultural segmentation approach. In Proceedings of the TTRA, Glasgow, UK, 25–27 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Manhas, P.S.; Manrai, L.A.; Manrai, A.K. Role of tourist destination development in building its brand image: A conceptual model. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2016, 21, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D. Marketing the competitive destination of the future. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Nicolau, J.L.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Assessing advertising in a hierarchical decision model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 40, 260–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, F.M.; Newman, A.; Liu, M. The moderating effect of individual level collectivist values on brand loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J. Brand awareness for entrepreneurial hotel chains: Perceived quality and brand loyalty. Anthropologist 2015, 19, 763–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.F.; Cohen, S.A.; Scarles, C. The power of social media storytelling in destination marketing. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S. The impact of destination personality dimensions on destination brand awareness and attractiveness: Australia as a case study. Tourism 2012, 60, 397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, R.B.; Kastenholz, E. Collaborative destination marketing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism & Management Studies, Algarve, Portugal, 26 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Karalkova, Y. Rural tourism destination competitiveness: Portugal vs. Belarus. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Politécnico, Bragança, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Blain, C.; Levy, S.E.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Destination branding: Insights and practices from destination management organizations. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A.; Piggott, R. New Zealand, 100% Pure. The creation of a powerful niche destination brand. J. Brand Manag. 2002, 9, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. International Tourism Highlights 2019 Edition; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, H.; Kim, L.H.; Im, H.H. A model of destination branding: Integrating the concepts of the branding and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaar, R. Destination branding: A snapshot. UW-L J. Undergrad. Res. 2013, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Manrai, L.A.; Manrai, A.K.; Friedeborn, S. Environmental determinants of destination competitiveness and its tourism attractions-basics-context, A-B-C, indicators. A review, conceptual model and propositions. J. Econ. Financ. Adm. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owiya, V.; Mulwa, J.M.; Kemboi, A. Strategic determinants of destination competitiveness: A case of Western tourist circuit, Kenya. East. Afr. J. Contemp. Res. (Eajcr) 2019, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Davidoff, D.M. Contact: Customer Service in the Hospitality and Tourism Industry; Prentice Hall Career and Technology: Texas, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Yaru, L.; Liu, X.; Jing, M. Study on the quality of service in rural homestay—Taking Shanli Lohas as an example. J. Tour. Hosp. 2018, 7, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.T.; Jahari, S.A. Destination image as a mediator between perceived risks and revisit intention: A case of post-disaster Japan. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C. Tourism in rural areas: Foundation, quality and experience. In Visions for Global Tourism Industry—Creating and Sustaining Competitive Strategies; Kasimoglu, M., Ed. 2012. Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/books/visions-for-global-tourism-industry-creating-and-sustaining-competitive-strategies/tourism-in-rural-areas-foundation-quality-and-experience (accessed on 16 June 2019). [CrossRef]

- Kresic, D.; Prebezac, D. Index of destination attractiveness as a tool for destination attractiveness assessment. Tourism 2011, 59, 497–517. [Google Scholar]

- Blinnikka, P.; Härkönen, A.; Väisänen, H.-M.; Tunkkari-Eskelinen, M. Finnish micro entrepreneurs’ perceptions of sustainability issues in rural tourism. In Proceedings in Rural Tourism as a Facilitator of Regional Development; Suni, J., Komppula, R., Eds.; Itä, Suomen yliopisto: Kuopio, Finland, 2014; ISBN 978-952-61-162-4. [Google Scholar]

- Potashova, I.; Girijchuk, D. The priority development of rural (agrarian) tourism in the Krasnodar region. E3s Web Conf. 2019, 91, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawardani, I.G.A.O.; Wiranatha, A.S.; Purbanto, I.G.R.; Nitivattananon, V. Identification tourism products and services provided at the rural tourism destinations in Bali. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2020, 1, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Nooripoor, M.; Khosrowjerdi, M.; Rastegari, H.; Sharifi, Z.; Bijani, M. The role of tourism in rural development: Evidence from Iran. GeoJournal 2020, 85, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B. Rural tourism: An overview. In The SAGE Handbook of Tourism Studies; Robinson, M., Jamal, T., Eds.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009; pp. 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Zaei, M.E.; Zaei, M.E. The impacts of tourism industry on host community. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 1, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tampakis, S.; Manolas, E.; Tampakis, V. Assessing tourist infrastructure in the island of Skiathos: The views of locals and visitors. Tour. Int. Multidiscip. J. Tour. 2012, 7, 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch, G.I.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Tourism, Competitiveness, and Societal Prosperity. J. Bus. Res. 1999, 44, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javanović, S.; Ilić, I. Infrastructure as important determinant of tourism development in the countries of southeast Europe. Ecoforum 2016, 5, 288–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J.R.; Crouch, G.I. A model of destination competitiveness/sustainability: Brazilian perspectives. Rev. De Adm. Publica 2010, 44, 1049–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raad, N.G. A strategic approach to tourism development barriers in Iran. J. Tour. Hosp. 2019, 8, 410–417. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, X.; Lee, S.K.; Ahn, Y.; Kiatkawsin, K. Tourist-perceived quality and loyalty intentions towards rural tourism in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Developing India as smart tourism destination – A Sap-Lap analysis. South Asian J. Tour. Heri. 2016, 9, 124–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ramseook-Munhurrun, P.; Naidoo, P.; Seebaluck, V.N.; Pillai, P. The impact of destination service quality on tourist satisfaction and loyalty: Evidence from Mauritius. In Proceedings of the International Academic Research Conference on Marketing & Tourism, Paris, France, 1–3 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.C.; Dias, A.M.C.D. Assessing the challenges of service quality in the Terra Quente Transmontana, Portugal. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 16, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, C.H.; Omar, K. The impact of service quality on tourist satisfaction: The case study of Rantau Abang Beach as a Turtle Sanctuary Destination. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, F.-Y.; Tsai, C.-Y. Relationships among service quality, leisure benefits, overall satisfaction, and revisit intention: Cultural parks as an example. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 2016, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, M. Analysis of information systems applied to evaluating tourism service quality based on organizational impact. J. Softw. 2012, 7, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring customer perception of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, J.J., Jr.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.T. Factors That Influence the Intentions to Revisit Korea of Vietnamese Tourists. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinakhat, P.; Viriyachaikul, V.; Vorasingha, Y. The international guests’ satisfaction about service quality of guesthouse in Sukhothai. J. Tour. Theory Res. 2018, 4, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-Ababneh, M. Service quality and its impact on tourist satisfaction. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2013, 4, 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Wolfe, K.; Kang, S.K. Image assessment for a destination with limited comparative advantages. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaco, F.T.; Richardson, S. An analysis on international tourists’ perceptions towards destination branding: “Visit Indonesia 2008” Marketing Campaign. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Research Symposium in Service Management, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 26–30 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, Z.; Sohail, M.; Myers, C.; San, C. Marketing of Australia to Malaysian consumers. Serv. Mark. Q. 2006, 28, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartner, W.C. Tourism Development—Principles, Processes, and Policies; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stepchenkova, S.; Mills, J.E. Destination image: A meta-analysis of 2000-2007 Research. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 575–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, U. Examining the relationships of cognitive, affective, and conative destination image: A research on Safranbolu, Turkey. Int. Bus. Res. 2016, 9, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourists’ images of a destination—An alternative analysis. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1996, 5, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.-S. The role of destination image in tourism: A review and discussion. Tour. Rev. 1990, 45, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, L. A review on tourist satisfaction of tourism destinations. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Logistics, Informatics and Service Science; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA; Dordrecht, The Netherlands; London, UK, 2013; pp. 593–604. [Google Scholar]

- Triyanto, I.C.G.; Musikavanhu, T.B. Rural tourism as a way to build economic independence. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, M.; Marzuki, A.; Abdullah, S. Rural Tourism in Malaysia; Penerbit USM: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2019; ISBN 978-967-461-357-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B. What is rural tourism? J. Sustain. Tour. 1994, 2, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okech, R.; Haghiri, M.; George, B.P. Rural tourism as a sustainable development alternative: An analysis with special reference to Luanda, Kenya. Culture: Revista de Cultura e Turismo 2012, 6, 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Paimin, N.F.V.; Modilih, S.; Mogindol, S.H.; Johnny, C.; Thamburaj, J.A. Community participation and barriers in rural tourism: A case study in Kiulu, Sabah. Shs Web Conf. 2014, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Luvanga, N.; Shitundu, J. The Role of Tourism in Poverty Alleviation in Tanzania; University of Dar-es-Salaam Press: Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kachniewska, M.A. Tourism development as a determinant of quality of life in rural areas. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2015, 7, 500–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, F.; Sazali, F.; Mohamed, B. Rural and community based tourism development in Malaysia: Prospects for homestays as a social economy enterprise. Team J. Hosp. Tour. 2013, 10, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Khound, J.M. Constraints and prospects of rural tourism development: An overview of tourism in Shyamgaon of Titabor of Jorhat, District (Assam). J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 1, 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Carneiro, M.J.; Lima, J.; Silva, A.L. Landscape and the rural tourism experience: Identifying key elements, addressing potential, and implications for the future. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1217–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndivo, R.M.; Waudo, J.N.; Waswa, F. Examining Kenya’s tourist destinations’ appeal: The perspectives of domestic tourism market. J. Tour. Hosp. 2012, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, W.-H.; Vinh, N.Q. An application of AHP approach to investigate tourism promotional effectiveness. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wilde, S.J.; Cox, C. Linking destination competitiveness and destination development: Findings from a mature Australian tourism destination. In Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Association (TTRA) European Chapter Conference—Competition in Tourism: Business and Destination Perspectives, Helsinki, Finland, 23–25 April 2008; pp. 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.; Pritchard, M.; Smith, B. The destination product and its impact on traveler perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moric, I. Clusters as a factor of rural tourism competitiveness: Montenegro experiences. Bus. Syst. Res. 2013, 4, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffi, G. A model of tourism destinations competitiveness: The case of the Italian destinations of excellence. Anu. Tur. Y Soc. 2013, 14, 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, M.R.; Bostani, M.K.; Anvari, M.R. Analysis and prioritization of factors affecting the tourists’ satisfaction (Case study: In Southern Khorasan Province). Iosr J. Eng. 2015, 5, 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tardivo, G.; Scilla, A.; Viassone, M. How to become a benchmark sustainable tourist destination? A descriptive model. Bus. Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fabricius, M. Competitive Strategies for Tourism Destinations; University of South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, M.; Weiermair, K. New perspectives of satisfaction research in tourism destinations. Tour. Rev. 2003, 58, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R. Harnessing local expertise and knowledge: A new concept in business tourism destination marketing. In Book of Proceedings Edited by Milovan Stanišić in Singidunum International Tourism Conference 2016; Singidunum University: Belgrade, Serbia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Žabkar, V.; Brenčič, M.M.; Dmitrović, T. Modelling perceived quality, visitor satisfaction and behavioral intentions at the destination level. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Impact of tourist perceptions, destination image and tourist satisfaction on destination. loyalty: A conceptual model. Pasos: Rev. De Tur. Y Patrim. Cult. 2013, 11, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akroush, M.N.; Jraisat, L.E.; Kurdieh, D.J.; Al-Faouri, R.N.; Qatu, L.T. Tourism service quality and destination loyalty—The mediating role of destination image from international tourists’ perspectives. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunalal, Z.I.; Kadir, A.R.; Taba, M.I.; Hamid, N. The influence of service quality dimensions, destination image, and satisfaction to tourist loyalty in Maluku Province. Sci. Res. J. 2017, V, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Govers, R. Virtual Tourism Destination Image: Glocal Identities Constructed, Perceived and Experienced. Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University, Erasmus Research Institute of Management. Available online: http://repub.eur.nl/res/pub/6981/EPS2005069MKT_9058921077_GOVERS.P (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Dolnicar, S.; Grun, B. Validly measuring destination image in survey studies. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echtner, C.; Ritchie, J.B. The meaning and measurement of destination image. J. Tour. Stud. 2003, 14, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ragavan, N.A.; Subramonian, H.; Sharif, S.P. Tourists’ perceptions of destination travel attributes: An application to International tourists to Kuala Lumpur. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, P.; Miranda, F.J.; Elias-Almeida, A. Importance/value analyses applied to image components of a tourism destination. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2012, 8, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Agapito, D.; Valle, P.; Mendes, J. The sensory dimension of tourist experiences: Capturing meaningful sensory-informed themes in Southwest Portugal. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L.; Kim, C. Destination competitiveness: Determinants and indicators. Tourism 2003, 6, 369–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-H.; Chang, J.C.; Cheng, S.-C.; Kuo, C.-M. Employee relationship and knowledge sharing: A case study of a Taiwanese finance and securities firm. Knowl. Manag. Res. Pr. 2004, 2, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: An integrated approach. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-S.; Byun, B.; Shin, S. An examination of the relationship between rural tourists’ satisfaction, revisitation and information preferences: A Korean case study. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6293–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulty, D.D. The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done? J. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.R.; Yi, Y.; Philipps, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. How to write up and report PLS analyses. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares: Concepts, Methods and Application; Esposito, V.V., Chin, W., Henseler, J., Wang, H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 645–689. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. Int. Mark. Rev. 2016, 33, 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M. Multigroup analysis in Partial Least Squares (PLS) path modeling: Alternative methods and empirical results. Adv. Int. Mark. 2011, 22, 195–218. [Google Scholar]

- Blazeska, D.; Milenkovska, A.; Stojmirova, M. Hotel image as an important prerequisite for creating a competitive advantage. In Proceedings in SITCON 2016—Singidunum International Tourism Conference; SITCON: Belgrade, Serbia, 2016; pp. 230–234. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelidou, N.; Siamagka, N.T.; Moraes, C.; Micevski, M. Do marketers use visual representations of destinations that tourists value? Comparing visitors image of a destination with marketer-controlled images online. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilim, Y.; Bilim, M.B. Does a destination have personality? Personality and image issues of a destination. Anthens J. Tour. 2014, 1, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. Tourist Engagement: Conceptualization, Scale Development and Empirical Validation. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Guelph, Ontario, Canada, September 2017. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/83a2/28c623adf00eca4c2044c43f9b48317cfa85.pdf.

- Haugland, S.A.; Håvard, N.; Bjørn, O.G.; Jarle, A. Development of tourism destinations. An integrated multilevel perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 268–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample (n = 293) | Semirural: Annah Rais (n = 158) | Rural: Bario Highlands (n = 135) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Category | Frequency (n) | % | Frequency (n) | % | Frequency (n) | % | |

| Gender | Male | 161 | 54.9 | 84 | 53.2 | 77 | 57.0 | |

| Female | 132 | 45.1 | 74 | 46.8 | 58 | 43.0 | ||

| Education Level | High school or below | 52 | 17.7 | 25 | 15.8 | 27 | 20.0 | |

| Diploma | 123 | 42.0 | 54 | 34.2 | 69 | 51.1 | ||

| Degree | 93 | 31.7 | 57 | 36.1 | 36 | 26.7 | ||

| Postgraduate | 9 | 3.1 | 6 | 3.8 | 3 | 2.2 | ||

| Others | 16 | 5.5 | 16 | 10.1 | - | - | ||

| Monthly Income (in RM) | <RM1500 | 48 | 16.4 | 46 | 29.1 | 2 | 1.5 | |

| RM1501 to RM3000 | 24 | 8.2 | 16 | 10.1 | 8 | 5.9 | ||

| RM3001 to RM4500 | 46 | 15.7 | 26 | 16.5 | 20 | 14.8 | ||

| RM4501 to RM6000 | 55 | 18.8 | 18 | 11.4 | 37 | 27.4 | ||

| RM6001 to RM7500 | 93 | 31.7 | 44 | 27.8 | 49 | 36.3 | ||

| RM7501 to RM9000 | 27 | 9.2 | 8 | 5.1 | 19 | 14.1 | ||

| No of Visit | One | 238 | 81.2 | 117 | 74.1 | 121 | 89.6 | |

| Two | 37 | 12.6 | 28 | 17.7 | 9 | 6.7 | ||

| Three | 18 | 6.1 | 13 | 8.2 | 5 | 3.7 | ||

| Country of Origin | Domestic | 181 | 61.8 | 98 | 62.0 | 83 | 61.5 | |

| International | 112 | 38.2 | 60 | 38.0 | 52 | 38.5 | ||

| Respondent’s profile (n = 293) | Mean (Overall) | SD (Overall) | Minimum | Maximum | Minimum | Minimum | Minimum | Maximum |

| Age (in years) | 35.8 | 12.63 | 16 | 60 | 16 | 60 | 18 | 55 |

| Construct | Item(s) | Loading | CR a | AVE b | Loading | CR a | AVE b | Loading | CR a | AVE b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample (n = 293) | Semirural (n = 158) | Rural (n = 135) | ||||||||

| Destination Appeal (DA) | DA_01 | 0.794 | 0.878 | 0.547 | 0.770 | 0.877 | 0.548 | 0.797 | 0.880 | 0.557 |

| DA_02 | 0.790 | 0.873 | 0.739 | |||||||

| DA_04 | 0.621 | 0.756 | 0.500 | |||||||

| DA_05 | 0.800 | 0.795 | 0.771 | |||||||

| DA_06 | 0.717 | 0.578 | 0.842 | |||||||

| DA_07 | 0.701 | 0.632 | 0.787 | |||||||

| Tourism Infrastructure (TI) | TI_01 | 0.772 | 0.937 | 0.711 | 0.719 | 0.926 | 0.676 | 0.825 | 0.942 | 0.730 |

| TI_02 | 0.816 | 0.803 | 0.809 | |||||||

| TI_03 | 0.889 | 0.873 | 0.880 | |||||||

| TI_04 | 0.871 | 0.824 | 0.898 | |||||||

| TI_05 | 0.869 | 0.834 | 0.884 | |||||||

| TI_06 | 0.839 | 0.871 | 0.826 | |||||||

| Service Quality (SQ) | SQ_01 | 0.777 | 0.871 | 0.693 | 0.675 | 0.819 | 0.604 | 0.873 | 0.910 | 0.772 |

| SQ_02 | 0.740 | 0.817 | 0.843 | |||||||

| SQ_03 | 0.877 | 0.830 | 0.918 | |||||||

| Destination Image (DI) | DI_01 | 0.830 | 0.847 | 0.583 | 0.805 | 0.868 | 0.625 | 0.892 | 0.797 | 0.508 |

| DI_03 | 0.792 | 0.870 | 0.533 | |||||||

| DI_04 | 0.781 | 0.853 | 0.553 | |||||||

| DI_06 | 0.635 | 0.607 | 0.804 | |||||||

| Destination Marketing Efforts (DM) | DM_02 | 0.880 | 0.857 | 0.669 | 0.887 | 0.862 | 0.677 | 0.875 | 0.865 | 0.682 |

| DM_03 | 0.712 | 0.742 | 0.738 | |||||||

| DM_04 | 0.852 | 0.832 | 0.858 | |||||||

| Full Sample (n = 293) | DA | DI | DM | SQ | TI |

| Destination Appeal (DA) | 0.740 | ||||

| Destination Image (DI) | −0.074 | 0.763 | |||

| Destination Marketing Efforts (DM) | 0.392 | 0.287 | 0.818 | ||

| Service Quality (SQ) | 0.228 | 0.314 | 0.627 | 0.832 | |

| Tourism Infrastructure (TI) | 0.217 | 0.220 | 0.423 | 0.652 | 0.843 |

| Semirural (n = 158) | DA | DI | DM | SQ | TI |

| Destination Appeal (DA) | 0.741 | ||||

| Destination Image (DI) | −0.055 | 0.791 | |||

| Destination Marketing Efforts (DM) | 0.324 | 0.344 | 0.823 | ||

| Service Quality (SQ) | 0.268 | 0.260 | 0.662 | 0.777 | |

| Tourism Infrastructure (TI) | 0.278 | 0.085 | 0.469 | 0.564 | 0.822 |

| Rural (n = 135) | DA | DI | DM | SQ | TI |

| Destination Appeal (DA) | 0.746 | ||||

| Destination Image (DI) | 0.010 | 0.713 | |||

| Destination Marketing Efforts (DM) | 0.532 | 0.246 | 0.826 | ||

| Service Quality (SQ) | 0.215 | 0.424 | 0.421 | 0.879 | |

| Tourism Infrastructure (TI) | 0.190 | 0.438 | 0.397 | 0.728 | 0.854 |

| Composite | cValue (=1) | 95% Confidence Interval | Compositional Invariance |

| Destination Appeal | 1.000 | [0.966; 1.000] | Yes |

| Destination Image | 1.000 | [1.000; 1.000] | Yes |

| Destination Marketing Efforts | 0.998 | [0.993; 1.000] | Yes |

| Service Quality | 1.000 | [1.000; 1.000] | Yes |

| Tourism Infrastructure | 0.995 | [0.995; 1.000] | Yes |

| Composite | Difference of the composite’s mean value (=0) | 95% confidence interval | Equal mean values |

| Destination Appeal | 0.182 | [−0.204; 0.193] | Yes |

| Destination Image | 0.069 | [−0.204; 0.203] | Yes |

| Destination Marketing Efforts | 0.175 | [−0.205; 0.186] | Yes |

| Service Quality | 0.405 | [−0.197; 0.190] | Yes |

| Tourism Infrastructure | 0.356 | [−0.198; 0.189] | Yes |

| Composite | Difference of the composite’s variance ratio (=0) | 95% confidence interval | Equal variances |

| Destination Appeal | 0.084 | [−0.241; 0.246] | Yes |

| Destination Image | 0.290 | [−0.305; 0.307] | Yes |

| Destination Marketing Efforts | −0.022 | [−0.269; 0.277] | Yes |

| Service Quality | −0.214 | [−0.253; 0.284] | Yes |

| Tourism Infrastructure | −0.339 | [−0.296; 0.319] | Yes |

| Full Sample (n = 293) | Semirural (n = 158) | Rural (n = 135) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | Path | Std. Beta | t-Value | Result | Std. Beta | t-Value | Result | Std. Beta | t-Value | Result |

| H1 | DA → DM | −0.343 | 4.466 | NS | 0.125 | 2.589 | S | 0.467 | 7.613 | S |

| H2 | TI → DM | −0.165 | 1.281 | NS | −0.035 | 0.554 | NS | 0.130 | 1.097 | NS |

| H3 | SQ → DM | 0.632 | 5.064 | S | 0.812 | 14.707 | S | 0.180 | 1.514 | NS |

| H4 | DI → DM | 0.034 | 0.357 | NS | 0.142 | 3.047 | S | 0.108 | 1.227 | NS |

| Construct | Full Sample (n = 293) | Semirural (n = 158) | Rural (n = 135) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | Q2 | f2 | R2 | Q2 | f2 | R2 | Q2 | f2 | |

| DA | 0.144 | 0.061 | 0.344 | ||||||

| TI | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.012 | ||||||

| SQ | 0.277 | 1.751 | 0.025 | ||||||

| DI | 0.036 | 0.081 | 0.015 | ||||||

| DM | 0.477 | 0.307 | 0.770 | 0.509 | 0.403 | 0.255 | |||

| Hypothesis | Path | Semirural | Rural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | Beta | t-Value | p-Value | ||

| H5a | DA → DM | 0.125 | 0.467 | 4.409 | 0.000 |

| H5b | TI → DM | −0.035 | 0.130 | 1.233 | 0.110 |

| H5c | SQ → DM | 0.812 | 0.180 | 4.831 | 0.000 |

| H5d | DI → DM | 0.142 | 0.108 | 0.344 | 0.366 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chin, C.H.; Lo, M.C.; Razak, Z.b.; Pasbakhsh, P.; Mohamad, A.A. Resources Confirmation for Tourism Destinations Marketing Efforts Using PLS-MGA: The Moderating Impact of Semirural and Rural Tourism Destination. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176787

Chin CH, Lo MC, Razak Zb, Pasbakhsh P, Mohamad AA. Resources Confirmation for Tourism Destinations Marketing Efforts Using PLS-MGA: The Moderating Impact of Semirural and Rural Tourism Destination. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176787

Chicago/Turabian StyleChin, Chee Hua, May Chiun Lo, Zaidi bin Razak, Pooria Pasbakhsh, and Abang Azlan Mohamad. 2020. "Resources Confirmation for Tourism Destinations Marketing Efforts Using PLS-MGA: The Moderating Impact of Semirural and Rural Tourism Destination" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176787

APA StyleChin, C. H., Lo, M. C., Razak, Z. b., Pasbakhsh, P., & Mohamad, A. A. (2020). Resources Confirmation for Tourism Destinations Marketing Efforts Using PLS-MGA: The Moderating Impact of Semirural and Rural Tourism Destination. Sustainability, 12(17), 6787. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176787