Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking in the Chinese Organizational Context: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Double-Edged Sword Effect on Employees’ Sustainable Organizational Identification

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study 1: Concepts and Dimensions of MPSRB

2.1. Definition of MPSRB

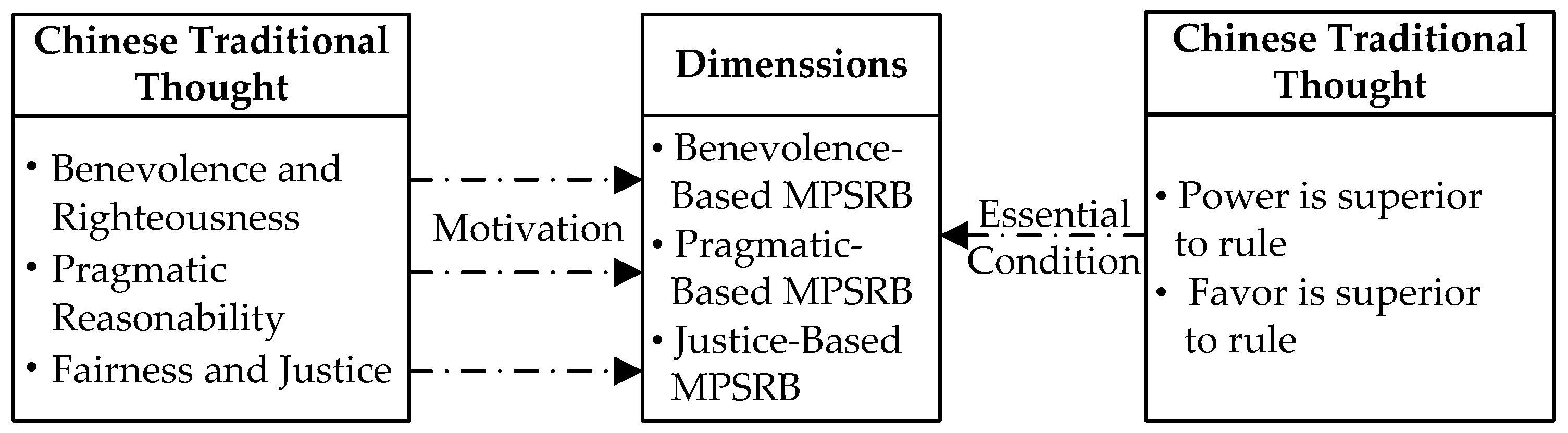

2.2. Traditional Chinese Cultural Background-Based and Dimensional Division of MPSRB

2.2.1. The Relationship between Power, Favor and Rule

Power Is Superior to Rule

Favor Is Superior to Rule

2.2.2. Benevolence, Pragmatic, and Justice in Confucianism

Benevolence and Righteousness

Pragmatic Reasonability

Fairness and Justice

2.2.3. Dimensions of MPSRB

3. Study 2 Scale Development of MPSRB

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Procedural

3.1.2. Data Collection and Samples

3.1.3. Measurement

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Results of the Interview

Screening

Classification

Item Refinement

3.2.2. Results of the Pre-Questionnaire Survey

Item Analysis

Reliability Analysis

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

3.2.3. Results of the Formal Questionnaire Survey

EFA and Reliability Analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4. Study 3: The Double-Edged Sword Effect of MPSRB

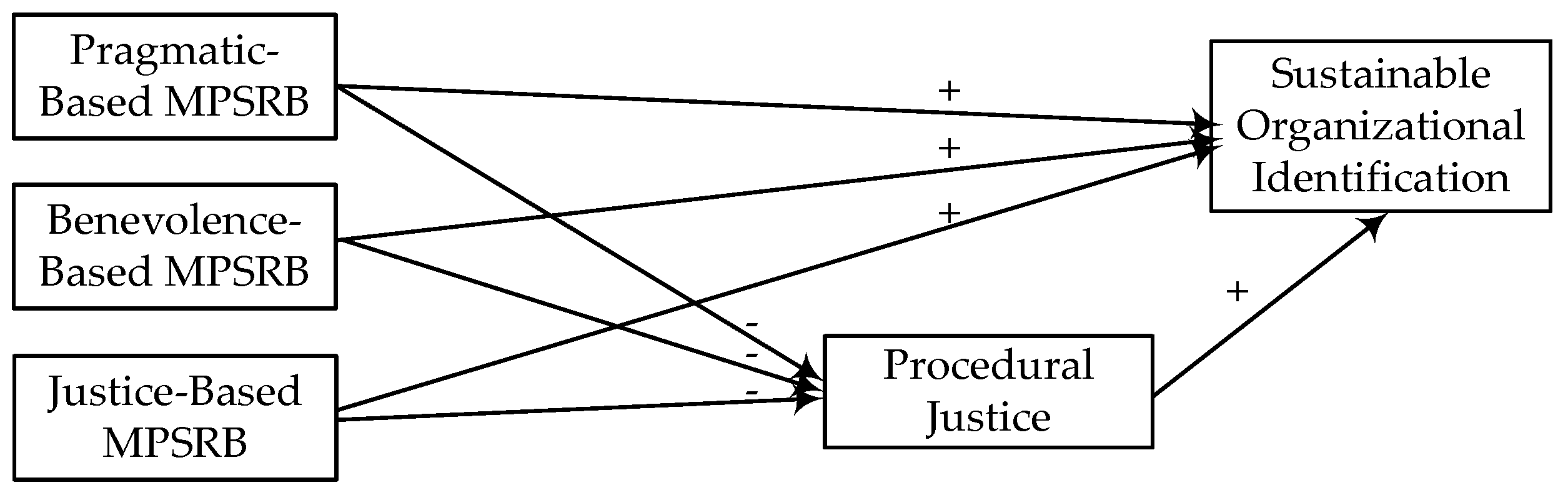

4.1. Theoretical Hypothesis

4.1.1. Bright Side of MPSRB: Its Positive Direct Effect on Sustainable Organizational Identification

4.1.2. Dark Side of MPSRB: Its Negative Indirect Effect on Sustainable Organizational Identification

4.2. Methodology

4.2.1. Data Collection and Samples

4.2.2. Measurement

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.3.2. Hypothesis Testing

Direct Effect

Mediating Effects

Total Effect

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Implications

(2) Valuing Pro-Sociality over Rule Compliance

(3) Compensating the Perception of Procedural Justice

5.3. Limitation and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Veiga, J.F.; Golden, T.D.; Dechant, K. Why managers bend company rules. Acad. Manag. Persp. 2004, 18, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P.C.; Davis, C.A.; Hancock, J.I.; Vardaman, J.M. When rule makers become rule breakers: Employee level outcomes of managerial pro-social rule breaking. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2010, 22, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, R.; Ling, W.Q. A review of the literature of pro-social rule breaking in organization and future prospects. Foreign. Econo. Manag. 2013, 33, 43–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.G.; Wang, Z.H. Influence mechanism of managerial pro-social rule breaking on employee behavior from the perspective of opposition between favor and reason: A cross-levels and longitudinal study. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 191–203. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Doing the job well: An investigation of pro-social rule breaking. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J.J.; Chau, S.L.; Mayer, D.M.; Gregory, J.B. Breaking rules for the right reasons? An investigation of pro-social rule breaking. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, J.M.; Gondo, M.B.; Allen, D.G. Ethical climate and pro-social rule breaking in the workplace. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J.J.; Gutworth, M.B. Loyal rebels? A test of the normative conflict model of constructive deviance. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Tian, X.M.; Liu, S.S. Does benevolent leadership increase employee pro-social rule breaking? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2015, 47, 637–652. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Ouyang, K.; Herst, D.; Farndale, E. Ethical leadership and employee pro-social rule-breaking behavior in China. Asian. Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Caldwell, J.; Ford, R.C.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Gresock, A.R. Should I serve my customer or my supervisor? A relational perspective on pro-social rule breaking. In Proceedings of the 67th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3–8 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S. Counter-Productive Work Behavior and Pro-Social Rule Breaking Behavior: Based on Compensatory Ethics View. Econ. Manag. 2015, 37, 75–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Borry, E.L.; Henderson, A.C. Patients, protocols, and prosocial behavior: Rule breaking in Frontline Health Care. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.R.; Upchurch, R.S.; Dickson, D. Restaurant Industry Perspectives on Pro-social Rule Breaking: Intent versus Action. Hosp. Rev. 2014, 31, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kahari, W.I.; Mildred, K.; Micheal, N. The contribution of work characteristics and risk propensity in explaining pro-social rule breaking among teachers in Wakiso District, Uganda. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, X.G.; Li, J.Z. Dual effects of managerial pro-social rule breaking on employee behavior in the Chinese context. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2015, 51, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H. The Trickle-Down Effect of Leaders’ Pro-social Rule Breaking: Joint Moderating Role of Empowering Leadership and Courage. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenkert, G.G. Innovation, rule breaking and the ethics of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHart-Davis, L. The unbureaucratic personality. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, J. Unbureaucratic Behavior among Street-Level Bureaucrats: The Case of the German State Police. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2017, 37, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, W.; Recker, J.; Kummer, T.F.; Kohlborn, T.; Viaene, S. Constructive deviance as a driver for performance in retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela-Huotari, K.; Edvardsson, B.; Jonas, J.M.; Sörhammar, D.; Witell, L. Innovation in service ecosystems—Breaking, making, and maintaining institutionalized rules of resource integration. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2964–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, N.; Jamshed, S.; Mustamil, N.M. Striving to restrain employee turnover intention through ethical leadership and pro-social rule breaking. Int. Online J. Educ. Leadersh. 2018, 2, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shum, C.; Ghosh, A.; Gatling, A. Prosocial rule-breaking to help coworker: Nature, causes, and effect on service performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D.; Li, N. Sustainable Influence of Manager’s Pro-Social Rule-Breaking Behaviors on Employees’ Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.S. White-collar crime: A review of recent developments and promising directions for future research. Annual. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 39, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 79–85, (In Chinese). ISBN 978-7-01-014714-7. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Liang, J.; Chou, L.F.; Cheng, B.S. Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: Research progress and future research directions. In Business Leadership in China: Philosophies, Theories, and Practices; Chen, C.C., Lee, Y.T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 171–205. ISBN 978-0521705431. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Hackett, R.D.; Liang, J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H. History of Ancient Chinese Thought; SDX Joint Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 281–284, (In Chinese). ISBN 978-7-108-05875-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.K. Face and favor: The Chinese power game. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.K. Self-practice and change of values in Chinese society. In Chinese Values; Yang, K.S., Ed.; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 101–145. ISBN 978-7-300-16548-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.W. Chinese people’s “big justice view” and its social operation mode. Open Times. 2010, 12, 84–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.S.; Chou, L.F.; Farh, J.L. Paternalistic Leadership Scale: The construction and measurement of ternary model. Indigen. Psychol. Res. 2000, 14, 3–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.L. Questionnaire Statistical Analysis Practice—SPSS Operation and Application; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010; ISBN 978-7-5624-5088-7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: A comment. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reade, C. Antecedents of organizational identification in multinational corporations: Fostering psychological attachment to the local subsidiary and the global organization. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 12, 1269–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S.; Diab, H.; Alhyari, S.; Sweis, R.J. Does ethical leadership reduce turnover intention? The mediating effects of psychological empowerment and organizational identification. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Peng, A.C.; Hannah, S.T. Developing trust with peers and leaders: Impacts on organizational identification and performance during entry. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1148–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Lind, E.A. A relational model of authority in groups. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 115–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Hannah, S.T.; Gok, K.; Arslan, A.; Capar, N. The moderated influence of ethical leadership, via meaningful work, on followers’ engagement, organizational identification, and envy. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017, 145, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Mayer, D.M.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Workman, K.; Christensen, A.L. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 115, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, A.A.; Demsetz, H. Production, information costs, and economic organization. Am. Econ. Rev. 1972, 62, 777–795. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Van den Bos, K. When fairness works: Toward a general theory of uncertainty management. Res. Organ. Behav. 2002, 24, 181–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. The Psychology of Procedural Justice: A Test of the Group-value Model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, G.S. What should be done with Equity Theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research; Gergen, K.J., Greenberg, M.S., Willis, R.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 27–55. ISBN 978-1-4613-3089-9. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, R.J. Entrepreneurs as Sophisticated Iconoclasts: Rational Rule-Breaking in an Experimental Game. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucus, M.S.; Norton, W.I.; Baucus, D.A.; Human, S.E. Fostering creativity and innovation without encouraging unethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenen, G.; Melkonian, T. Fairness and commitment to change in M&As: The mediating role of organizational identification. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Li, C.; Wu, K.; Long, L. Procedural justice and voice: A group engagement model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, S.L.; Tyler, T.R. Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extra-role behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erat, S.; Kitapçı, H.; Akçin, K. Managerial Perception and Organizational Identity: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, B.P.; Moorman, R.H. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 527–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-60918-230-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T. Doing good is not enough, you should have been authentic: Organizational identification, authentic leadership and CSR. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Value | Interview | Preliminary Survey | Formal Survey | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | Frequency | Ratio | ||

| Gender | Male | 20 | 52.6 | 80 | 39.8 | 144 | 47.1 |

| Female | 18 | 47.4 | 121 | 60.2 | 162 | 52.9 | |

| Age | 25 or below | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 2.5 | 17 | 5.6 |

| 26–35 | 31 | 81.6 | 148 | 73.6 | 211 | 69.0 | |

| 36–45 | 7 | 18.4 | 42 | 20.9 | 65 | 21.2 | |

| 46 or above | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 3.0 | 13 | 4.2 | |

| Education | Junior college or below | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 5.0 | 4 | 1.3 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 27 | 71.1 | 156 | 77.6 | 279 | 91.2 | |

| Master’s degree or above | 11 | 28.9 | 35 | 17.4 | 23 | 7.5 | |

| Hierarchy | Ordinary employees | 22 | 57.9 | 72 | 35.8 | 168 | 54.9 |

| Junior manager | 11 | 28.9 | 71 | 35.3 | 65 | 21.2 | |

| Middle management | 5 | 13.2 | 55 | 27.4 | 63 | 20.6 | |

| Top management | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.5 | 10 | 3.3 | |

| Items | Factor Loading | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preliminary Survey | Formal Survey | |||||

| He (she) bends the rules to help his subordinates overcome difficulties in life. | 0.819 | 0.792 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to favor older workers or women. | 0.847 | 0.806 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to improve the welfare of his subordinates in financial difficulties. | 0.632 | 0.800 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to help his subordinates overcome their work problems. | 0.714 | 0.766 | ||||

| He (she) bends the decision-making procedure to improve work efficiency. | 0.830 | 0.741 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to better serve customers. | 0.651 | 0.795 | ||||

| He (she) bends organizational rules to simplify workflow. | 0.637 | 0.808 | ||||

| He (she) does not strictly follow the rules that inconvenience his work. | 0.643 | 0.788 | ||||

| He (she) bypasses some steps of a workflow to work more efficiently | 0.672 | 0.765 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to ensure that his subordinates get what they deserve. | 0.685 | 0.776 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to make decisions that he thought fair. | 0.757 | 0.823 | ||||

| He (she) bends the rules to make decisions that made most of his subordinates feel fair. | 0.669 | 0.861 | ||||

| Dimensions | Factor Loading | Standard Error | T Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benevolence-based | 0.801 | 0.054 | 15.998 *** |

| AVE = 0.595 | 0.793 | 0.054 | 15.745 *** |

| CR = 0.839 | 0.774 | 0.057 | 15.208 *** |

| 0.715 | 0.052 | 13.631 *** | |

| Pragmatic-based | 0.742 | 0.053 | 14.469 *** |

| AVE = 0.584 | 0.761 | 0.059 | 14.995 *** |

| CR = 0.852 | 0.807 | 0.058 | 16.302 *** |

| 0.717 | 0.056 | 13.811 *** | |

| 0.791 | 0.055 | 15.851 *** | |

| Justice-based | 0.788 | 0.052 | 15.578 *** |

| AVE = 0.665 | 0.801 | 0.05 | 15.909 *** |

| CR = 0.844 | 0.855 | 0.055 | 17.466 *** |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Benevolence-based MPSRB | (0.771) | ||||

| 2 Pragmatic-based MPSRB | 0.533 *** | (0.764) | |||

| 3 Justice-based MPSRB | 0.607 *** | 0.532 *** | (0.815) | ||

| 4 Benevolent Leadership | 0.371 *** | 0.333 *** | 0.396 *** | (0.867) | |

| 5 Moral Leadership | 0.552 *** | 0.382 *** | 0.480 *** | 0.371 *** | (0.848) |

| Variable | MEAN | S.D. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Gender | 1.497 | 0.501 | 1 | |||||||

| 2 Age | 2.334 | 0.724 | −0.183 *** | 1 | ||||||

| 3 Education | 2.816 | 0.597 | 0.122 * | −0.181 *** | 1 | |||||

| 4 Hierarchy | 1.842 | 0.893 | −0.084 | 0.253 *** | −0.208 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5 MPSRB_P | 3.109 | 0.887 | −0.005 | 0.083 | −0.117 * | 0.044 | 1 | |||

| 6 MPSRB_B | 2.903 | 0.904 | 0.016 | 0.135 ** | −0.232 *** | −0.051 | 0.489 *** | 1 | ||

| 7 MPSRB_J | 2.825 | 0.976 | 0.006 | 0.144 ** | −0.228 *** | −0.018 | 0.522 *** | 0.583 *** | 1 | |

| 8 PJP | 2.205 | 1.105 | 0.049 | −0.089 | 0.143 * | −0.015 | −0.482 *** | −0.484 *** | −0.504 *** | 1 |

| 9 SOIDP | 2.693 | 1.184 | 0.030 | 0.047 | 0.005 | −0.044 | 0.239 *** | 0.261 *** | 0.241 *** | 0.017 |

| PJP | SOIDP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Controls | |||||

| Gender | 0.051 | 0.120 | 0.090 | 0.050 | 0.019 |

| Age | −0.105 | 0.018 | 0.112 | 0.042 | 0.038 |

| Education | 0.250 * | −0.004 | 0.000 | 0.146 | 0.147 |

| Hierarchy | 0.040 | −0.024 | −0.077 | −0.038 | −0.032 |

| Independent | |||||

| MPSRB_P | −0.302 *** | 0.158 * | 0.236 ** | ||

| MPSRB_B | −0.274 *** | 0.204 * | 0.275 ** | ||

| MPSRB_J | −0.282 *** | 0.122 | 0.195 * | ||

| Mediator | |||||

| PJP | 0.259 *** | ||||

| △R2 | 0.026 | 0.326 | 0.007 | 0.090 | 0.038 |

| △F | 2.518 * | 62.452 *** | 0.652 | 12.320 *** | 16.142 *** |

| Estimate | S.E. | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPSRB_P→SOIDP | 0.203 | 0.100 | 2.556 | 0.011 |

| MPSRB_B→SOIDP | 0.232 | 0.126 | 2.660 | 0.008 |

| MPSRB_J→SOIDP | 0.161 | 0.099 | 1.825 | 0.068 |

| Effect | Bootstrapping Test | Sobel Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Value | p-Value | |||

| MPSRB_P→PJP→SOIDP | −0.0780 | [−0.1460, −0.0317] | −3.0281 | 0.0025 |

| MPSRB_B→PJP→SOIDP | −0.0709 | [−0.1414, −0.0248] | −2.8387 | 0.0045 |

| MPSRB_J→PJP→SOIDP | −0.0730 | [−0.1337, −0.0309] | −2.9634 | 0.0030 |

| BC Method | PC Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval | TTS | Interval | TTS | |

| MPSRB_P→PJP→SOIDP | [−0.159, −0.030] | 0.001 | [−0.148, −0.024] | 0.002 |

| MPSRB_B→PJP→SOIDP | [−0.155, −0.019] | 0.004 | [−0.145, −0.015] | 0.008 |

| MPSRB_J→PJP→SOIDP | [−0.148, −0.023] | 0.003 | [−0.141, −0.019] | 0.006 |

| Path | BC Method | PC Method | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval | TTS | Interval | TTS | |

| MPSRB_P→SOIDP | [−0.046, 0.280] | 0.154 | [−0.038, 0.286] | 0.133 |

| MPSRB_B→SOIDP | [−0.022, 0.342] | 0.087 | [−0.022, 0.348] | 0.085 |

| MPSRB_J→SOIDP | [−0.097, 0.278] | 0.347 | [−0.102, 0.271] | 0.376 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, G.; Choi, Y. Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking in the Chinese Organizational Context: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Double-Edged Sword Effect on Employees’ Sustainable Organizational Identification. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6786. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176786

Lv Y, Liu X, Li G, Choi Y. Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking in the Chinese Organizational Context: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Double-Edged Sword Effect on Employees’ Sustainable Organizational Identification. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6786. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176786

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Yanyan, Xiaoguang Liu, Guomin Li, and Yongrok Choi. 2020. "Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking in the Chinese Organizational Context: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Double-Edged Sword Effect on Employees’ Sustainable Organizational Identification" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6786. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176786

APA StyleLv, Y., Liu, X., Li, G., & Choi, Y. (2020). Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking in the Chinese Organizational Context: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Double-Edged Sword Effect on Employees’ Sustainable Organizational Identification. Sustainability, 12(17), 6786. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176786