Abstract

Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking (MPSRB) is a prevalent leadership behavior in China, characterized by conflict between favor and rule. Despite emerging interest in this behavior, two theoretical questions remain unsolved. First, its definition, dimensions, and measurement in the Chinese context are still lacking or improper; second, its double-edged sword effect on employees’ attitude is rarely empirically examined. This paper conducts three studies to solve these questions. In study 1, based on an analysis of the Chinese traditional culture, three dimensions of MPSRB (i.e., benevolence-based, pragmatic-based, and justice-based) were identified. In study 2, a scale of MPSRB containing 12 items was developed through an interview, preliminary, and formal questionnaire survey. In study 3, employees’ sustainable organizational identification perception (SOIDP) was studied as the dependent variable, to analyze and verify the double-edged sword effect of MPSRB by hierarchical regression and structural equation modeling (SEM) methods on the data gathered through the three stages from 380 employees. The results show that the three dimensions of MPSRB have a direct positive impact on employees’ SOIDP and, simultaneously, they have an indirect negative impact through the mediating role of procedural justice perception.

1. Introduction

Managers at all levels of an organization are often faced with a moral dilemma where rules conflict with human sentiment. For example, if an employee has been working overtime all weekend to deal with an urgent and difficult issue for the company, but there is no clear policy in place to compensate him (her) with time or money, should the supervisor bend the rules to give him (her) a few days off or an extra monetary incentive, or just simply say “thank you”? According to a survey of CEOs, more than 70% of managers in such situations tend to choose breaking the rules to achieve practical pro-social goals [1]. This phenomenon is academically known as Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking (MPSRB) [2], which is more prevalent in the Chinese context.

Effective managerial behavior contributes to employees’ sustainable perception and attitude in the workplace, which further leads to organizations’ sustainable competitiveness, performance, and development. However, as a kind of managerial behavior, the consequence of MPSRB is controversial in theory. From the perspective of particularism, MPSRB show such qualities as managers’ virtue, goodwill, and responsibility, and provide valuable “resources” to employees, leading to sustainable positive attitudes among employees [3]. However, from the perspective of universalism, even motivated by altruism, MPSRB will undermine the authority and credibility of the institution’s system, increase the possibility of leaders’ opportunistic behaviors and exploitation of their subordinates in future transactions, and lead to unsustainable attitudes among employees [2]. It is clear that MPSRB is not only the product of managers’ moral dilemmas, but also the contradictory combination of human sentiment and reason. “Pro-social” reflects the basic emotional need, while “rule breaking” reflects the abandonment of reason. Moreover, their influence on employees’ attitudes is also complex, and there may be a double-edged sword effect [4].

Previous studies about prosocial rule breaking primarily focused on the employee level. Morrison [5] was the first to explicitly introduce this construct, and he defined it as “employees intentionally violates a formal organizational policy, regulation, or prohibition with the primary intention of promoting the welfare of the organization or one of its stakeholders”. He points out that this kind of behavior is mainly driven by three motivations, namely to improve work efficiency, help colleagues and help customers, and he developed a six-item scale. However, this is only a response scale in a specific scenario experiment. If other scholars want to use this scale, they must replicate the experimental scenario or revise the scale. Dahling et al. [6] developed a 13-item general prosocial rule breaking scale based on the three-dimensional structure of Morrison [5], which has been widely used, and promoted the empirical study of the antecedent factors of prosocial rule breaking among employees.

In general, these studies focus on four themes: first, personal factors, such as risk-taking propensity, conscientiousness, organizational identity, and core self-evaluation [6,7,8]; second, leadership factors, such as benevolent leadership, and moral leadership [7,9,10]; third, organizational factors, such as organizational fairness, counterproductivity norms, and bureaucracy [11,12,13]; fourth, job characteristics, such as job meaning, autonomy, job demand, and work systems [14,15]. Although most of these studies focus on the employee level, the findings of individual, organizational, and job characteristics factors also apply to the manager level.

Employees’ prosocial rule breaking should be generally studied as the dependent variable, while MPSRB should be studied as independent variables to explore its impact on employees’ sustainable attitudes and behavior. Apart from obvious differences in their theoretical constructions, their causes and manifestations are also distinct. Therefore, it is necessary to redefine MPSRB and develop a new scale.

Some exploratory studies have explored the causes and manifestations of MPSRB. For example, Veiga et al. [1] carried out interview research on CEOs and found that MPSRB occurred mostly for three reasons, namely improving performance, because rules were wrong, and social embedding. Liu and Li [16] summarized three main manifestations of MPSRB in the Chinese context based on interviews. At present, most studies on the consequences of MPSRB only focus on its positive side. For example, through the social learning process, a trickle-down effect will occur, leading to employees’ prosocial rule breaking, which is moderated by leadership empowerment and employees’ courage [17]. Moreover, similar behaviors, such as “positive deviant leadership”, “positive political behavior”, “non-bureaucratic personality”, and “non-bureaucratic behavior” were found to alleviate the conflict between rigid rules and flexible organizational goals, and contribute to organizational procedure improvement, change, project duration and success, creative destruction and sustainable performance, etc. [18,19,20,21,22].

However, some studies have found the opposite, pointing out that the MPSRB will not only damage the interests of other group members [6], but also undermine the institution’s system of organization and negatively influence employee attitudes, such as procedural justice, psychological contract, and attribution to leadership [2], which indirectly lead to negative working behaviors among employees and turnover intention [2,23] and decrease service performance [24]. Hence, MPSRB is possibly a double-edged sword for organizations, exerting positive and negative effects on employees’ sustainable attitude and behavior simultaneously, thereby attracting further studies to explore their respective theoretical mechanisms. The two opposite mechanisms are moderated by the employee’s values and psychological maturity, and the organization’s management practices [4,16,25], and under the different conditions of these moderation factors, positive and negative effects compete with each other and tradeoffs [4,16,25].

Although some progress has been made in the research on MPSRB, in general, it is still lacking. The research is still in the exploratory stage and the theoretical framework is not perfect due to two deficiencies. Firstly, the concept definition, dimension dividing, and measurement are based on the study of Dahling et al. [6] at the employee level, which cannot fully reflect all the characteristics of the manager level and, particularly, the analysis in the Chinese organizational context is also lacking, which limits the validity of previous conclusions. Secondly, empirical evidence of the double-edged sword effect is scarce except in the research of Li et al. [25], making the breadth and the existence of this effect unproven and insufficient.

To bridge the above theoretical gaps, three studies were conducted subsequently, and their contents and logical links are as follows: study 1 was conducted to conceptualize the construction of the MPSRB, and identify its sub-dimensions based on the analysis of traditional Chinese culture, as this provides a theoretical basis for the two subsequent studies. Study 2 was conducted to develop the scale for MPSRB following the standard scale development procedures, and to test its reliability and construct validity, which provided a measurement for the last study. Lastly, study 3 was conducted as a specific application of the scale and as a test for its predictive validity.

2. Study 1: Concepts and Dimensions of MPSRB

2.1. Definition of MPSRB

Morrison [5] first defined the prosocial rule-breaking behavior of employees and further explained its three main characteristics. First, this behavior is motivated by altruistic motivation, for the benefit of stakeholders, such as customers, colleagues, shareholders, teams, and the whole organization. Although sometimes it may produce self-interested results, these are only side effects rather than the purpose. Second, this behavior violates the formal rules that are formulated from top to bottom, institutionalized, and controlled by the bureaucratic hierarchy, rather than the informal rules derived from tradition, custom, or ethics. Thus, it is distinguished from constructive or positive deviant behaviors and is only one type of them. Finally, the act is intentional and active, rather than accidental, unintentional, or compelling, thus reflecting the quality of the subject’s responsibility.

Byrant et al. [2] were the first to explicitly focus on the prosocial rule breaking at the manager level. Their concept definition followed the train of Morrison [5], transformed the behavior subject from employee to manager, and inherited Morrison’s three characteristics. This definition is clear, specific, and operable. However, in a previous exploratory interview [16], it was still found that the denotation of this definition may be too broad. However, some types of behaviors conforming to this definition do not match the requirement of our research and may interfere with some assumed causality. Cropanzano et al. [26] pointed out that if a construct related to employee behavior was not subdivided from the views of motivation, intensity, severity, and object, it would lead to an overlap between variables and the instability of the causality relationship. Therefore, in addition to the above three characteristics, it is necessary to further refine the denotation of the construct in terms of object and severity.

First, the policies and institutions violated by managers should be made within the organization and should not involve judicial issues. The organizations’ daily operations need to abide by the rules, including external mandatory laws and regulations concerning labor relations, state-owned asset management, and environmental protection, and so on. However, the violation of those rules would raise serious legal issues related to white-collar crime or organizational corruption, which will lead to a wider and more profound influence [27]. Nevertheless, such issues do not fall within the scope of our research.

Second, the rules violated by managers should only involve the internal management of the organization, such as personnel, salary, production, and customer service, which are more easily perceived by employees, have a higher correlation with employees’ interests and have a more direct impact on employees’ behaviors. It should not include rules relating to external business operations, such as mergers and acquisitions, competition, and alliances.

Finally, MPSRB should not lead to serious negative consequences, such as resulting in a huge loss to the organization, endangering personal position and reputation, or hurting other people. They are just extreme events, which rarely happen, and are not prevalent for organizations [1]. The effect of this kind of managerial behavior on employees is more likely to be one-sided and negative, so it should be distinguished from prosocial rule breaking with less severe consequences.

Therefore, integrating the definition of Morrison [5] and the above analysis, this article will redefine MPSRB as designed “to improve the welfare of the organization or other stakeholders, managers at all levels of the organization intentionally violate the formal policies, regulations, and prohibitions formulated within the organization, concerning internal management issues, and without serious consequence”.

2.2. Traditional Chinese Cultural Background-Based and Dimensional Division of MPSRB

In Chinese organizations, the prevalence of MPSRB can be traced back to China’s distinct traditional social structure and cultural background.

2.2.1. The Relationship between Power, Favor and Rule

Power Is Superior to Rule

In the agricultural society of ancient China, because of the immobility of plow lands and the necessity of cooperation, the production and living pattern of family members dwelling together was formed, in which the family elders had natural powers. This pattern was further extended to a social structure of “family→clanstate→nation”, in which a hierarchical society based on the authority of the elders is naturally formed, and a comprehensive ruling order is formed after integrating the factors of education, politics, and culture [28]. This order emphasizes the five cardinal relationships, respecting the elder, the distinction between the noble and humble, and the distinction between the superior and inferior. In such a society, the elder, noble, and superiors have the arbitrary power to unconditionally control resources and issue orders. Indeed, there are rules in this order, including rules of etiquette, but they are only made to ensure the implementation of arbitrary power and hierarchical order, instead of forming rules through negotiations and votes of different classes, as in Western civilization [28]. Therefore, in traditional Chinese society, power is superior to rules; in fact, rules are just the byproduct and safeguard of arbitrary power, but cannot restrain power.

Although modern China is no longer a patriarchal society, the social–psychological characteristics of “awe and obedience to the authority of the superior” persist deeply. In organizational management practice, there is a large power distance between the leader and the subordinate. The leader holds the power from his status, legal principle, or personal authority, and adopts dictatorial, authoritarian, controlling, and strict leadership [29], whereas the subordinate shows the traditional tendency of submission to authority, filial piety, conservatism, endurance, and fatalism [30]. Hence, managers’ power dominates over rules in organizations.

Favor Is Superior to Rule

In ancient Chinese society, etiquette was a system of customary laws, which was theoretically deepened by Confucius, who interpreted rites with benevolence and ascribed them to and associated them with the basic human psychological needs, sentiments, instinct, and desires [31]. Furthermore, based on basic humanity and sentiments such as family affection, the mind of cannot bear to see the sufferings of others, and putting oneself in others’ way, another basis of etiquette is deduced—the establishment of a humanitarian interpersonal relationship within the family and among members of society—which not only emphasizes the hierarchical order, but also kindheartedness [31]. The phrases of renqing and guanxi, which are frequently talked about by the Chinese, are the derivative products, external forms, and secular representations of this humanitarian interpersonal relationship. Thus, rules were derived from favor or human sentiments. Chinese people should trade off favor and rule when dealing with such issues. When necessary, even rules can make concessions to favor [32].

In China’s ancient rural society, characterized by agricultural civilization, people attached to and stuck to the plow land, and the population mobility was weak. Most people lived in a small acquaintance society under the framework of villages and clans all their lives. In such a society, there is no need for universalistic contracts, rules, or even texts. People understand each other and communicate frequently, and they trust because of familiarity. In solving the problems of interpersonal interaction, it is more effective to rely on the particularistic favor, rather than on rules [28].

This idea of “favor is superior to rule” has continued in the organizational management practices of contemporary China, which often makes managers choose to sacrifice rules when rules deviate from the generally accepted human nature.

2.2.2. Benevolence, Pragmatic, and Justice in Confucianism

In traditional Chinese ideology and culture, although the status of rules is lower than power and favor, the violation of rules is costly and may bring adverse consequences to individuals and organizations. Why do managers altruistically break the rules? The context surrounding benevolence, pragmatism, and justice in traditional Chinese culture can explain the underlying motivation.

Benevolence and Righteousness

Benevolence and righteousness are the core elements of China’s Confucian moral system. Benevolence means to have a heart of love and compassion for others, while righteousness means to treat others properly and suitably. The early theory of benevolence and righteousness focused on blood relationships. Later, it gradually extended its application to other people around family members, requiring kindness and morality toward other friends, colleagues, and even strangers. Based on this, a set of norms and requirements for behavior and conduct has been developed.

Confucius ascribed the basis of benevolence and righteousness to human nature’s innate need, which made benevolence and righteousness have natural rationality. Since the Qin and Han dynasties, Confucians have combined this thought with the theory of “Yin and Yang and the Five Elements”, and take it as an ethical ontology, known as the Way of Heaven, the Principle of Heaven, the Born Nature, and the Virtue Nature, which must be obeyed unquestionably [31].

In applying such ethical norms to the organizational situations, managers must treat their subordinates with kindness [29]. When subordinates encounter difficulties or make excusable mistakes, managers usually choose to sacrifice rules to help or protect their subordinates. This behavioral orientation stems from three mechanisms: first, in the general cases without serious consequences, managers tend to actively comply with the ethical norm; secondly, according to the “role theory”, to reduce the social pressure, managers choose to passively accept the role expectation of “being benevolent than a heartless leader” constructed by society. Finally, from the perspective of social interaction, managers hope to establish a “heart for heart” relational community with subordinates through their benevolent behavior [32].

Pragmatic Reasonability

In China’s traditional society, the economy was characterized by smallholder production, and Confucian scholars particularly emphasized the daily practical household affairs. As a result, ancient intellectuals and craftsmen focus most of their attention on practical matters, such as family ethics, agriculture, the improvement of people’s livelihoods, and so on. This means that the dominant philosophical thought remains at the level of empiricism for a long time, forming a particular cultural orientation named “pragmatic reasonability”, which was characterized by emphasizing practical utility rather than abstract thinking [31].

Within this ideology, a complete system of concepts and abstract symbols cannot be developed, so there is no universal standard of rationality, and the judgment of things is quite flexible. Static and mechanical rules often do not apply to a variety of situations. The criterion for judging whether and how a thing should be done is its ultimate actual utility achieved [31], which is often referred to as “no matter the cat is black or white as long as it catches mice”. Therefore, Chinese values are highly utilitarian, objective, and practical. The highest goal of Chinese people is to synthesize the three secular values of life, wealth, and career [33].

In modern Chinese enterprises, the highest self-actualization need for people in the workplace is the pursuit of organizational goals and further personal achievement [33]. When rigid rules are cumbersome, inefficient, and hindered the practical purpose, people will be pragmatic and flexible. They will break the rules when necessary for better utility at a specific time, place, and situation, rather than obey the rules mechanically and unconditionally, which is consistent with the value orientation of pragmatic reasonability.

Fairness and Justice

The traditional Chinese culture has long focused on fairness and justice, which are considered to be ensured by establishing rules and laws. However, since the traditional view of order is aesthetic rather than logical, and follows particularism rather than universalism, it leads to the formation of a specific view of fairness and justice. When it comes to issues such as resource allocation and conflict resolution, the judgment criteria of fairness and justice are more dependent on the particularity, diversity, and contextuality of events [34].

This standard of fairness and justice, which emphasizes “too much of a good thing but not enough of a right” is flexible, but lacks an external, absolute, and objective order. It can only appeal to the ontology of the Confucian philosophical system—the Tao of Heaven, which is seen as the objective law that governs all things. However, in the Confucian cosmology based on the heaven–human induction, the Tao of Heaven is anthropomorphized and then emotional, which finally makes the criterion of fairness and justice the human emotion or motivation [31]. In other words, when most people emotionally feel that something is just and morally acceptable, there is no doubt that it is just.

Within such a standard, substantive justice is more important than procedural justice, and the principle of valuing results over processes and substance over procedures is upheld [31]. Just arbitrament can only rely on the personal morality and motivation of the adjudicators. The Chinese people have always been fond of “good man politics”, “Justice Bao”, and “imperial envoy”, which reflect this ideological tradition.

In Chinese enterprises, when solving internal conflicts and distribution issues related to salary, training, promotion, and so on, the imperfection and insufficiency of formal rules often result in dilemmatic situations, in which compliance with rules may lead to unfair results, thereby confusing managers with respect to outcome fairness and procedural fairness. According to the fairness orientation in Chinese traditional culture, managers often abandon procedural fairness for outcome fairness, thus violating the rules. As outcome fairness follows human nature, morality, and public opinion, it is worthwhile.

2.2.3. Dimensions of MPSRB

The above discussion on the relationship between power, favor, and rule can explain the question of “why rules can be violated” in China, which is an essential condition for MPSRB. On the other hand, the discussion about benevolence, pragmatism, and justice can explain the question of “why should the manager violate the rules” from the perspective of motivation. Driven by different motivations, MPSRB may differ in its manifestations, beneficiaries, and employees’ perceptions. Therefore, this paper attempts to explain the dimensions of MPSRB from the view of motivation, based on Chinese traditional ideology and culture.

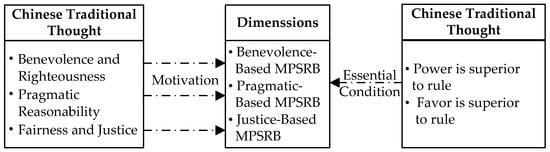

Specifically, for the consideration of benevolence and righteousness, managers will exhibit benevolence-based MPSRB, motivated by compassion and care for subordinates. For the consideration of pragmatic reasonability, managers will exhibit pragmatic-based MPSRB, motivated by improving work efficiency and organizational performance. For the consideration of fairness and justice, managers will exhibit justice-based MPSRB, motivated by ensuring outcome fairness in conflict resolution and resource allocation, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dimension structure of Managerial Pro-Social Rule Breaking (MPSRB).

3. Study 2 Scale Development of MPSRB

To better measure MPSRB, this study will develop a scale of MPSRB based on the previously mentioned concept definition and dimension structure, following the scale development procedure proposed by Churchill [35]. Its reliability, convergent validity, and discriminative validity were verified through sequential interviews, pre-surveys, and formal surveys.

3.1. Methodology

3.1.1. Procedural

Firstly, given the inability to obtain enough items from the previous literature, this study will conduct an in-depth interview to form the initial scale by induction. We collected as many typical cases of MPSRB as possible through interviews and then screened, classified, and refined these cases to form an initial scale.

Secondly, a preliminary questionnaire survey was conducted on the initial scale. Item analysis, reliability analysis, and exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were carried out on the survey data successively. After eliminating inappropriate items, a formal scale for MPSRB emerged.

Finally, a further formal questionnaire survey was conducted by using the previously mentioned formal scale. Reliability analysis and EFA were carried out again. The convergent validity of each subscale and their discriminant validity with each other and with moral leadership and benevolent leadership were tested through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

3.1.2. Data Collection and Samples

Participants in the three surveys were required to have a college degree or above, work experience for at least 1 year, and work in an organization with more than 30 people. The sample size of in-depth interviews was 38. The questionnaire survey was conducted by the charging service of the “questionnaire star” platform. In the preliminary survey, a total of 274 questionnaires were distributed, and 73 invalid questionnaires were eliminated based on reverse items and answer time. A total of 201 valid questionnaires were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 73.36%. In the formal survey, a total of 463 questionnaires were distributed, of which 306 were valid, with an effective recovery rate of 66.09%. The sample distribution is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample distribution.

3.1.3. Measurement

The measurement of MPSRB adopts the initial scale in the preliminary survey and the formal scale in the formal survey. The MPSRB is a kind of leadership behavior; the more frequently it occurs, the more prevalent it is. Therefore, the frequency Likert five-point scoring method was adopted. The numbers from one to five represent “always”, “often”, “sometimes”, “rarely”, and “never”, respectively. In addition, to enable the participants to make an independent judgment of each item without interference from the preceding and the following items, in the pre-survey, items were arranged in a disordered order rather than by clustering each sub-scale.

The measurement of “benevolent leadership” and “moral leadership” adopted the ternary paternalistic leadership scale developed by Cheng et al. [36], with each variable containing five items. The numbers from one to five mean “strongly agree”, “agree”, “uncertain”, “disagree”, and “strongly disagree”, respectively.

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Results of the Interview

Before the interview began, the connotation, denotation, and structure of MPSRB were introduced to the interviewees. Given that this construct points to leadership behavior, which is better reflected through the specific cases, the respondents were asked to describe as many typical cases of MPSRB as possible, based on their experiences or indirect observations. We then made recordings on the spot. A total of 113 initial cases were obtained, which were then proofread, polished, analyzed, and interpreted one by one. In addition, the items of the initial scale were generated by further screening, classification, and refinement.

Screening

Following the definition given above, the initial cases were screened to eliminate the ones that did not meet the needs of this study or deviated from this definition. For example: “managers often report and financially process a large engineering project as several small divided ones, to lower the level of project review and improve work efficiency; “In recent years, although the government has prohibited nation-owned enterprises from distributing extra benefits without permission, the leaders still do this to ensure our income”; “employees of our company have two wage cards, only one of which is used to pay personal income tax, which is beneficial for us”. These cases were eliminated for reasons involving judicial issues and external operations or inducing serious consequences. Finally, 87 valid cases were retained.

Classification

The valid cases were classified by three researchers, and the steps were as follows: (a) judging which dimension each case belonged to (the results of the three researchers were completely consistent); and (b) secondary classification within each dimension. The classification criteria were set by the three researchers, in consultation with each other. A pilot category was discussed and established for reference, which contains six examples, such as “if the family member of an employee is hospitalized and needs companionship, the leader provides special treatment in the work schedule, attendance, and payment, ”, “if an employee constantly lived in different cities and far away from his (her) spouse, the leader asked the employee to go home for a short time in the name of the business trip and reimburse some expenses”. The remaining 81 cases were classified by the three researchers separately, and then discussed and judged together for the cases without consensus. Finally, 13 categories were formed, and the three dimensions of benevolence-based, pragmatic-based, and justice-based included four, five, and four categories, respectively, and each category contained approximately five to eight cases.

Item Refinement

The cases contained within each category are summarized and refined. Focusing on one category, two descriptive sentences were created as the measurement items based on the commonness of all cases included, which have a general meaning and cover all cases. Replicating the above work for all the categories, an initial scale containing 26 items was formed, two of which were designed as reverse items. The three dimensions of benevolence-based, pragmatic-based, and justice-based contained eight, 10, and eight initial items, respectively.

3.2.2. Results of the Pre-Questionnaire Survey

Item Analysis

The purpose of item analysis is to test the contribution of each item to the whole scale and eliminate the items with smaller contributions. The process is as follows: focused on one dimension, calculating the total score of this dimension; sorting the samples according to the total score; taking the former and latter 27% as high and low score groups, respectively; conducting the independent sample t-test between the two groups, for each item [37]; deleting the item with the lowest T value and repeating the above operation until the T value of all items is above eight and achieves a significance of p < 0.001. Repeating the above operations for every dimension, a total of 16 items were retained after an item analysis. For the three dimensions of benevolence-based, pragmatic-based, and justice-based, five, six, and five items were retained, respectively.

Reliability Analysis

Cronbach’s α coefficient was used to test the internal consistency and to further purify the three subscales. The α coefficient of subscales was required to be above 0.7. If a single item does not meet one of the following requirements, then it should be eliminated: (1) the “corrected item-total correlation” (CITC) is above 0.5; (2) the “Cronbach’s α if item detailed” is lower than the α coefficient of the whole subscale; (3) the “squared multiple correlations” (SMC) is higher than 0.35 [37]. The above steps were repeated until all three conditions were met.

When the CITC of one item in each of the three subscales does not meet the requirements, the values are 0.387, 0.336, and 0.303, respectively, and they are eliminated. Within the purified subscales, the benevolence-based dimension contains four items, with α coefficient of 0.832; the pragmatic-based dimension contains five items, with α coefficient of 0.776; and the justice-based dimension contains four items, with α coefficient of 0.778.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

EFA was performed on the 13-item scale. We choose the principal component method to extract factors and choose the varimax to rotate. Only the factors whose eigenvalue was greater than one were retained. The results show that the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) value was 0.895, the Bartlett test achieved a significance of p < 0.001, and three factors were identified. One item that belonged to benevolence-based MPSRB was eliminated, whose loading coefficients on two factors are simultaneously more than 0.5. We make EFA again, and the results are as shown in the second column of Table 2, showing that the factor structure of the remaining 12 items is completely consistent with our assumptions, and can explain 65.987% of the variance.

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis of preliminary survey.

3.2.3. Results of the Formal Questionnaire Survey

EFA and Reliability Analysis

EFA was carried out on the formal scale again with formal survey data. The KMO value was 0.899, and the Bartlett test reached a significance of p < 0.001. A total of 70.891% of the variance was explained, and the factor structure of the scale was completely consistent with the pre-survey. The result are as shown in the third column of Table 2.

In addition, Cronbach’s α coefficient of all variables was analyzed, wherein the benevolence-based MPSRB was 0.853, the pragmatic-based MPSRB was 0.875, and the justice-based MPSRB was 0.854, the benevolent leadership was 0.927, and the moral leadership was 0.937.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

The first-order CFA was carried out with AMOS24.0 software, and the model fit index was as follows: χ2 = 313.521, df = 199, χ2/df = 1.575, RMR = 0.053, RMSEA = 0.043, NFI = 0.934, RFI = 0.924, IFI = 0.975, TLI = 0.971, CFI = 0.975. These indices all met the requirements, indicating a good model fit.

Following Fornell and Larcker [38], convergence validity can be evaluated by three indicators, as follows: all standardized factor loadings are greater than 0.5 and reach a significance level of p < 0.05; constituent reliability (CR) is above 0.7; average variance extraction (AVE) is above 0.5. The results of the convergence validity test are shown in Table 3. Given the research needs, only the results of three subscales of the MPSRB are reported.

Table 3.

Convergence validity test for formal scale.

The results show that the factor loadings of all items were between 0.715 and 0.855, all above 0.7, the AVE values of all three factors were greater than 0.5, and CR values were greater than 0.8, indicating that the MPSRB scale had a good convergent validity.

Following the suggestion of Fornell and Larcker [38], if the correlation coefficient between every pair factor is lower than their arithmetic square root of AVE, it indicates that the two factors have good discriminative validity. The arithmetic square root of the AVE value of each factor and the pairwise correlation coefficient are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Discriminative validity test for the formal scale.

The results show that every value on the diagonal is greater than all the correlation coefficients on the same rows and columns, indicating that there is a good discriminant validity among the three dimensions of MPSRB, benevolent leadership, and moral leadership.

4. Study 3: The Double-Edged Sword Effect of MPSRB

Sustainable organizational identification and procedural justice were widely proven to be prominent outcome variables of many types of leadership. As a result, this study aims to establish a theoretical model embracing these two constructs and MPSRB, and then verify it. The purpose of this study is to analyze the double-edged sword effect of MPSRB, and test the predictive validity of the scale developed in study 2.

4.1. Theoretical Hypothesis

Sustainable organizational identification was defined as “the perception of oneness with or belongingness to an organization, where the individual defines him or herself in terms of the organization(s) in which he or she is a member” [39]. Employees’ perception of sustainable organizational identification is conducive to their understanding and acceptance of the organizational premises, leading to pro-organizational attitudes and behaviors, such as work involvement, affective commitment, and high in-role and extra-role performance [40]. Therefore, improving employees’ sustainable organizational identification is important for organizational management. Several studies have shown that sustainable organizational identification of employees is influenced by contextual factors, such as organizational characteristics, management practices, and personal factors, such as employee values, personality, and demographics [41]. Among them, leaders’ ethical behaviors have been proven to play an important role [42]. However, as an ethically paradoxical leadership behavior, MPSRB helps the subordinates, guarantees outcome fairness, and improves organizational efficiency, which makes it ethical. On the other hand, it breaks the organizational formal rules and is therefore unethical. As a result, it is more likely to have a double-edged sword effect on sustainable organizational identification.

4.1.1. Bright Side of MPSRB: Its Positive Direct Effect on Sustainable Organizational Identification

Benevolence-based MPSRB manifests through managers being caring about the interests of their subordinates and actively helping them to overcome difficulties in work and life. It shows the leaders’ quality of goodwill, which is the strong willingness and motivation to help inferiors, thereby convincing subordinates that, in their future work, they will receive more support from their leaders [4,16]. Justice-based MPSRB manifests through managers maintaining distributive justice, in terms of performance appraisals, promotion, payment, and training opportunities, even at the cost of intentionally breaking the rules. It shows leaders’ quality of integrity, which is the adherence to the principles of outcome fairness. In the Chinese context, influenced by the traditional cultural orientation of pragmatic rationality, people particularly prefer outcome fairness to procedures, so this kind of integrity is easily recognized and accepted by employees [4,16]. Pragmatic-based MPSRB manifests through managers’ actions for work process improvement and reformation in relation to red tape. It shows leaders’ quality of ability in terms of improving work efficiency and organizational welfare, creative destruction, and breaking out of old and bad routines [4,16]. To summarize, the three dimensions of MPSRB, respectively, reflect their three traits of goodwill, integrity, and ability [4]. According to the “trait theory” of trust, these three traits contribute to the formation of employees’ leadership trust [43]. Leadership trust in an organization is a vertical, particularistic interpersonal trust, which reflects a psychological state wherein employees are willing to put themselves in a vulnerable position based on positive expectations of leadership intentions and behaviors [44]. To some extent, the leader plays the role of the organization’s spokesperson; thus, the trust in the leader can be extended to the whole organization and generate sustainable organizational identification [45].

The benevolence-based MPSRB provides subordinates with timely help, not only with indirect real resources, such as money and time for overcoming difficulties, but also with emotional and symbolic resources, such as respect, support, care, love, and tolerance [46]. Justice-based MPSRB protects the rights and interests deserved by subordinates and shows respect and approval from leaders, which demonstrates their social status and can also be regarded as symbolic resources provided by the supervisors [46]. Pragmatic-based MPSRB is helpful for employees to simplify the work process, improve work convenience, consume fewer work resources, and further improve work performance, which can be regarded as a kind of leadership support [47]. All of these taken together will have two consequences. First, these behaviors conform to the general ethical norms, making the leader an “ethical manager” in the organization. Through the interaction with subordinates, these ethical standards are established and strengthened, making the organization more attractive and desirable [48]. Second, the behaviors make employees feel that they are valuable and respected members of the organization, which has been proven to significantly enhance employees’ sustainable organizational identification [48,49].

We thus propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a (H1a).

Benevolence-based MPSRB has a direct positive impact on employees’ sustainable organizational identification.

Hypothesis 1b (H1b).

Pragmatic-based MPSRB has a direct positive impact on employees’ sustainable organizational identification.

Hypothesis 1c (H1c).

Justice-based MPSRB has a direct positive impact on employees’ sustainable organizational identification.

4.1.2. Dark Side of MPSRB: Its Negative Indirect Effect on Sustainable Organizational Identification

According to the theory of social contract and neo-institutional economics, an enterprise is an institution organized by a group of individuals in transactions, based on contracts. These contracts are generated by negotiation and stipulate the rights and obligations of all parties [50]. In practice, these contracts are embedded in the management systems of the organization and have the functions of ensuring a fair transaction, reducing transaction uncertainty, and predicting transaction behaviors. However, the violation or the inconsistency in their execution reduces the positive expectation of future transactions and thus generates negative employee attitudes.

Perceived procedural justice is an employee’s sense of the fairness of an organization’s allocation (transaction) process, which reflects their cognition about the principles, methods, and procedures of allocation [51]. A higher procedural justice perception compensates for distributive justice and serves as a heuristic cue to help employees avoid the fear of being exploited in uncertain circumstances, and then leads to more positive work behaviors [52]. However, the extent of employees’ procedural justice perception depends, to some degree, on the neutrality, trustworthiness, and accepted identity of leaders [53]. Therefore, as a kind of leadership behavior, MPSRB has an important impact on employees’ procedural justice perception.

The fairness judgment theory proposed six principles for employees to judge procedural fairness, namely consistency, being unbiased, accuracy, modifiability, representativeness, and ethics [54]. Among them, employees are most sensitive to consistency [43], which requires the organization to treat all employees indistinguishably, and that the organizational system or rules should be consistently implemented in different situations and times. Although the MPSRB is motivated by altruism, they cause some rules to be ignored or broken in certain circumstances, thus violating the consistency principle. Inconsistency in the rules’ execution will make employees perceive a lack of authority and credibility in the organizational institution.

In addition, if managers’ rule breaking is not investigated, if there is a lack of supervision, or if they receive positive feedback, they will be encouraged to rationalize the violations and show more of that in the future [55]. However, in many cases, it is difficult to judge whether managers’ rule breaking is motivated by altruism or egoism and whether it can promote the benefits of the organization or employees [56]. A sophisticated violator may harm employees’ welfare by breaking the rules under the guise of prosocial behavior or altruism [55]. Moreover, as the focal point of the organization, managers tend to be a role model for such behavior, which can be imitated by other employees through social learning and, gradually, a culture of rule breaking can be formed.

Therefore, MPSRB tends to put the organization’s formal rules in a state that may be violated at any time, thus weakening employees’ procedural justice perception. Procedural justice is an important element for employees to evaluate how they are treated by the organization and then decide what kind of work behaviors to respond to; here, the social identity mechanism plays an important role [57,58].

According to the group engagement model, employees believe that their procedural justice standard reflects the fundamental values of organizations [59]. Treating an employee fairly in the procedure will make them perceive themselves as a valuable and full-fledged member [46], and also perceive that the organization cares about their feelings of self-esteem and self-worth, which symbolically affirms their status in the organization and represents their good relationship with the organization [53]. Procedural justice can induce a sense of pride and respect [59], a sense of belonging as members of the organization, and can further increase sustainable organizational identification [60].

We thus propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a).

Benevolence-based MPSRB negatively affects sustainable organizational identification through the mediating effect of procedural justice perception.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b).

Pragmatic-based MPSRB negatively affects sustainable organizational identification through the mediating effect of procedural justice perception.

Hypothesis 2c (H2c).

Justice-based MPSRB negatively affects sustainable organizational identification through the mediating effect of procedural justice perception.

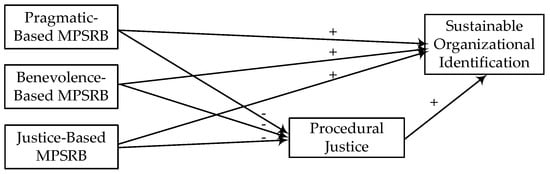

To summarize, the theoretical model is as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Double-edged sword effect of MPSRB.

4.2. Methodology

4.2.1. Data Collection and Samples

We recruit 429 employees from three manufacturing enterprises in Xi’an, China, to participate in the questionnaire survey. The data were gathered across three stages to minimize common method variance. The measurement of MPSRB was finished at the time T1, the measurement of PJP at the time T2, a month later, and the measurement of OIDP at the time T3, a month later. A total of 49 questionnaires were eliminated for reasons of turnover, incompletion, and failure in reverse items, and then 380 valid questionnaires remained, with an effective recovery rate of 88.58%; 50.3% of them were male. Those aged 25 or below, 26 to 35, 36 to 45, and 46 or above accounted for 6.6%, 61.8%, 23.2%, and 8.4%, respectively. Those with a college degree, a bachelor’s degree, and a master’s degree or above accounted for 20.2%, 73.7%, and 6.1%, respectively. The ordinary employees, junior managers, middle managers, and senior managers accounted for 45.8%, 27.4%, 23.7%, and 3.2%, respectively.

4.2.2. Measurement

MPSRB was measured by the 12-item scale developed in study 2. The Cronbach’s α coefficients of pragmatic-based MPSRB, benevolence-based MPSRB, and justice-based MPSRB were 0.863, 0.852, and 0.862, respectively. sustainable Organizational identification was measured by a scale developed by Mael and Ashforth [61], which contains six items, and with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.892. Procedural justice was measured by a scale developed by Niehoff and Moorman [62], which contains six items, and with a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.881. The last two scales adopted the Likert five-point scoring method, with numbers approximately between one and five representing “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”.

4.3. Results

4.3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

The results of descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficient analysis are shown in Table 5. The mean and standard deviation of all variables are within a reasonable range. The correlation coefficients between the three dimensions of MPSRB and sustainable organizational identification were above 0.2 and reached a significance of p < 0.001. The correlation coefficients of the three dimensions MPSRB and procedural justice were lower than −0.4 and reached a significance of p < 0.001. The hypothesis model was preliminarily verified.

Table 5.

Descriptive and correlation analysis.

4.3.2. Hypothesis Testing

Hierarchical regression and structural equation modeling (SEM) were the two most commonly used methods for hypothesis testing in the field of organizational behavior. They were different in their data requirements, statistical principles, and modeling. To enhance the credibility of the conclusions, this paper uses both methods to test our hypotheses, including direct, mediating, and total effects. The analysis of hierarchical regression used SPSS 19.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and the analysis of structural equation modeling used AMOS 24.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Direct Effect

(a) Results of the Hierarchical Regression

Hierarchical regression was conducted with procedural justice and sustainable organizational identification as dependent variables and the results are shown in Table 6. In model 5, the coefficients of benevolence-based MPSRB (β = 0.275, p < 0.01), pragmatic-based MPSRB (β = 0.236, p < 0.01), and justice-based MPSRB (β = 0.195, p < 0.05) were all positive and reached a significance of p < 0.05 at least.

Table 6.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis.

(b) Results of the Structural Equation Modeling

The structural equation modeling was conducted, and the model fit index was as follows: χ2 = 375.563, df = 242, χ2/df = 1.552, RMSEA = 0.038, NFI = 0.938, RFI = 0.929, IFI = 0.977, TLI = 0.974, CFI = 0.977. These indices all met the requirements, indicating a good model fit. The results of the standardized estimate are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Results of the standardized estimate of structural equation modeling (SEM).

Although the estimates of the effects of all three dimensions of MPSRB on sustainable organizational identification were lower than the results of hierarchical regression, they were significant. Benevolence-based MPSRB (β = 0.275) and pragmatic-based MPSRB (β = 0.236) reached a significance of p < 0.05 at least. Justice-based MPSRB was the lowest and only 0.161, but still reached a significance of p < 0.1.

Both results indicated that all three dimensions of MPSRB have a significant positive impact on employees’ sustainable organizational identification perception. Therefore, hypotheses 1a, 1b, and, 1c are supported empirically.

Mediating Effects

(a) Results of The Hierarchical Regression

In model 2 of Table 6, the coefficients of benevolence-based MPSRB (β = −0.274, p < 0.001), pragmatic-based MPSRB (β = −0.302, p < 0.001), and justice-based MPSRB (β = 0.282, p < 0.001) were all significantly negative, indicating that the three dimensions of MPSRB had significant negative impacts on employees’ procedural justice perception. Moreover, in model 5, the coefficient of procedural justice perception was 0.259 (p < 0.001), indicating that it had a significant positive impact on sustainable organizational identification perception.

To more accurately analyze the size and significance of the mediating effect, the SPSS macro PROCESS developed by Hayes [63], an instrument for mediation and moderation analysis, was used to conduct the bootstrapping and Sobel tests, and the samples were repeatedly extracted 5000 times with a confidence interval of 95%. The results are shown in Table 8. The size of the mediating effect of the path “MPSRB_P→PIP→OIDP” was −0.0780 (Z = −3.0281, p < 0.01), 95% confidence interval was [−0.1460, −0.0317], excluding zero. The size of the mediating effect of the path “MPSRB_B→PIP→OIDP” was −0.0709 (Z = −2.8387, p < 0.01), 95% confidence interval was [−0.1414, −0.0248], excluding zero. The size of the mediating effect of the path “MPSRB_J→PIP→OIDP” was −0.0730 (Z = −2.9634, p < 0.01), 95% confidence interval was [−0.1337, −0.0309], excluding zero.

Table 8.

Results of mediation effects based on hierarchical regression.

(b) Results of the Structural Equation Modeling

The bootstrapping analysis based on SEM was conducted using both the bias-corrected percentile method and percentile method, and the samples were repeatedly extracted 5000 times with a confidence interval of 95%. The results are shown in Table 9. Regardless of the bias-corrected percentile and percentile method, the 95% confidence intervals of all three mediation effects excluded zero, and their two-tailed significance values were all lower than 0.008 (p < 0.01).

Table 9.

Results of mediation effects based on SEM.

Both results indicated that employees’ procedural justice perception significantly and negatively mediated the relationship between all three dimensions of MPSRB and employees’ sustainable organizational identification perception. Therefore, hypotheses 2a, 2b, and, 2c are supported empirically.

Total Effect

The total effect is equal to the sum of the direct effect and the mediating effect. The above results show that the direct effect was positive and the mediating effect was negative. In this situation, the total effect can reflect whether the difference between the direct effect and the mediating effect is significant.

(a) Results of the Hierarchical Regression

In model 4 of Table 6, the coefficients of three dimensions of MPSRB were all positive but lower than those of model 5 (direct effects). To be specific, benevolence-based MPSRB (β = 0.204) and pragmatic-based MPSRB (β = 0.158) only reached a significance of p < 0.05, while the coefficient of the justice-based MPSRB was only 0.122 and not significant.

(b) Results of the Structural Equation Modeling

The results of total effects based on SEM are shown in Table 10. Regardless of the bias-corrected percentile and percentile method, the 95% confidence intervals of all three total effects included zero, and their two-tailed significance values all exceeded 0.085 (p > 0.05) and were not significant.

Table 10.

Results of total effects based on SEM.

The results indicate that the direct effects of the three dimensions of MPSRB were bigger than their mediating effects. However, the significances of their differences were inconsistent. Although the total effects of benevolence-based MPSRB and pragmatic-based MPSRB were significant in the results of the hierarchical regression, the three dimensions of MPSRB were not significant in the results of SEM. To be prudent, we can conclude that there were no significant differences between direct effects and mediating effects.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

(1) We extend the focus of prosocial rule breaking from the employee level to the manager level, which expands the research scope of this variable, and will promote further attention on its causes, manifestation, and consequences at the manager level. From the perspective of the kinds of rules violated and their severity, we define MPSRB more explicitly, which avoids the potential risk of overlap with other variables and the instability of its causal relationship. Based on Chinese traditional culture, we explore the construct’s structure, enhancing the applicability of this variable in explaining the indigenous phenomenon in Chinese, and deepening the research on leadership behavior.

(2) Our conclusions enrich the theoretical framework of “leadership behavior→employees’ sustainable organizational identification perception”. In addition to ethical leadership [42], transformational leadership [64], authentic leadership [65], and other types of leadership, this study on MPSRB adds a new antecedent variable to this theoretical framework. Previous studies have shown that leadership behaviors that conform to widely accepted moral norms and support employees have a significant positive influence on employee’s sustainable organizational identification. However, the effect of MPSRB is found to be different in this paper. Among the three dimensions of MPSRB, one is not significant, and the other two only achieve significance of p < 0.05. The reason lies in its dark side, which partially neutralizes the positive effect. This shows the complexity of the relationship of “leadership behavior→employees’ sustainable organizational identification” and opens a new window for future research.

(3) With sustainable organizational identification as the dependent variable, the double-edged sword effect of MPSRB is analyzed and confirmed. This conclusion integrates the previous perspectives on its positive role [17,19,20] or negative role [23,24], and has important implications for the more general theoretical question of “MPSRB→employees’ attitude/behavior”. This provides some empirical evidence for the theoretical framework proposed by Liu and Wang [14] and Liu and Li [16]. Moreover, the analysis of the negative mediating effect of procedural justice provides empirical evidence for the second mechanism in the theoretical model of Bryant et al. [2]. The antagonistic relationship between the positive and negative effects of MPSRB has been confirmed by Li et al. [25]. However, this study has confirmed the competitive relationship between the two, which has enriched the theoretical vision of the double-edged sword effect of MPSRB.

(4) The MPSRB scale developed in the Chinese context provides a reliable measurement tool for future empirical studies on the antecedents and consequences of MPSRB.

5.2. Practical Implications

(2) Valuing Pro-Sociality over Rule Compliance

Contemporary China as a society that still prefers favor over rules; therefore, the bright side of MPSRB on employees’ sustainable organizational identification is slightly greater than the dark side, and its total effect is generally positive. When a conflict between rules and favor is unavoidable, managers should be encouraged to sacrifice rules for pro-social purposes, adhering to the principle of “choosing the lesser of two evils”. However, such cases should be regarded as an exception in management practices, rather than as a set of universal ethical norms and principles. In addition, this choice should vary for types of MPSRB. Since the total effect of justice-based MPSRB on employees’ sustainable organizational identification is weaker than the other two dimensions, managers should be more cautious when confronted with the conflict between substantive fairness and rules.

(3) Compensating the Perception of Procedural Justice

Since the dark side of MPSRB occurs by reducing the sense of procedural justice, enterprises should regard procedural fairness as a key point of management. In order to neutralize the negative effects of MPSRB, measures should be taken to improve employees’ procedural justice perception. First, active communication strategies should be applied so employees can understand the reason why the leadership has deviated from standard rules, be aware of their leader’s pro-social motive, and avoid negative attribution. Second, in the processes of rulemaking and decision making, managers should consider the demands and interests of different groups of employees to make sure they are treated fairly from the beginning. Third, the processes of rulemaking and decision making should be open and transparent to employees, and their voice and participation should be encouraged using trade unions, opinion consultation, employee representative conferences, and voting.

5.3. Limitation and Future Directions

This study also has some limitations. For example, the research objective briefly focuses on “managers” and does not consider the differences of behavior between the top, middle, and junior managers. The analysis was primarily carried out in the context of mainstream Chinese culture, but differences in the subcultural context were not fully considered. Future studies may consider further detailed considerations of prosocial rule breaking by managers at different levels and in different subcultures. In addition, the newly developed measurement of MPSRB requires further empirical verification.

6. Conclusions

Firstly, this paper defined the concept and connotation of MPSRB. It is pointed out that, in addition to the three characteristics proposed by Morrison [5], namely altruistic motivation, formal rules, and voluntariness, another three characteristics were identified, namely rules that are made within the organization, those only relating to the internal management, and those with no serious consequences.

Secondly, the Chinese traditional cultural background and structure of MPSRB were analyzed. It is pointed out that the preference of favor and power over rules is the essential condition that leads to MPSRB; moreover, the cultural orientation of benevolence and righteousness, pragmatic reasonability, and fairness and justice induce different motivations for managers to exhibit such behaviors. According to this, we identify three dimensions of MPSRB, which are benevolence-based, pragmatic-based, and justice-based.

Thirdly, the MPSRB scale was developed with good reliability and validity. Through interviews, typical cases were obtained and the initial scale was formed. The initial scale was refined through a preliminary survey. The reliability and validity of the final scale were then tested by the formal survey. A 12-item MPSRB scale was formed, in which the benevolence-based, pragmatic-based, and justice-based dimensions included four, five, and three items, respectively.

Fourthly, MPSRB is a double-edged sword for employees’ sustainable organizational identification perception; in addition to its positive direct impact, there is also a negative indirect impact through the mediation of procedural justice perception.

Although this article has its basis in China, and the MPSRB scale developed in study 2 is more suitable for Chinese employees, the double-edged sword effect discussed in study 3 is universal. Its positive direct effect and the negative mediating effect of MPSRB on SOIDP exist not only in the Chinese context but also in other countries, varying only in their intensity. For example, the negative mediation effect of PIP may be stronger in the context of Western culture than in the context of Chinese culture. As a result, the conclusions of this study are transnationally valuable and meaningful.

Author Contributions

Data curation, Y.L.; formal analysis, G.L.; methodology, X.L.; project administration, Y.L.; supervision, Y.C.; writing—original draft, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 71602136, 11901422, and 71373170.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 71602136, 11901422, and 71373170). The authors express their gratitude to the team members for their help with the data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Veiga, J.F.; Golden, T.D.; Dechant, K. Why managers bend company rules. Acad. Manag. Persp. 2004, 18, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P.C.; Davis, C.A.; Hancock, J.I.; Vardaman, J.M. When rule makers become rule breakers: Employee level outcomes of managerial pro-social rule breaking. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2010, 22, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, R.; Ling, W.Q. A review of the literature of pro-social rule breaking in organization and future prospects. Foreign. Econo. Manag. 2013, 33, 43–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.G.; Wang, Z.H. Influence mechanism of managerial pro-social rule breaking on employee behavior from the perspective of opposition between favor and reason: A cross-levels and longitudinal study. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 26, 191–203. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Doing the job well: An investigation of pro-social rule breaking. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J.J.; Chau, S.L.; Mayer, D.M.; Gregory, J.B. Breaking rules for the right reasons? An investigation of pro-social rule breaking. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaman, J.M.; Gondo, M.B.; Allen, D.G. Ethical climate and pro-social rule breaking in the workplace. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahling, J.J.; Gutworth, M.B. Loyal rebels? A test of the normative conflict model of constructive deviance. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Tian, X.M.; Liu, S.S. Does benevolent leadership increase employee pro-social rule breaking? Acta Psychol. Sin. 2015, 47, 637–652. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S.; Ouyang, K.; Herst, D.; Farndale, E. Ethical leadership and employee pro-social rule-breaking behavior in China. Asian. Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Caldwell, J.; Ford, R.C.; Uhl-Bien, M.; Gresock, A.R. Should I serve my customer or my supervisor? A relational perspective on pro-social rule breaking. In Proceedings of the 67th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Management, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 3–8 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Xu, S. Counter-Productive Work Behavior and Pro-Social Rule Breaking Behavior: Based on Compensatory Ethics View. Econ. Manag. 2015, 37, 75–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Borry, E.L.; Henderson, A.C. Patients, protocols, and prosocial behavior: Rule breaking in Frontline Health Care. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2020, 50, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.R.; Upchurch, R.S.; Dickson, D. Restaurant Industry Perspectives on Pro-social Rule Breaking: Intent versus Action. Hosp. Rev. 2014, 31, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kahari, W.I.; Mildred, K.; Micheal, N. The contribution of work characteristics and risk propensity in explaining pro-social rule breaking among teachers in Wakiso District, Uganda. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, X.G.; Li, J.Z. Dual effects of managerial pro-social rule breaking on employee behavior in the Chinese context. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2015, 51, 187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Yang, H. The Trickle-Down Effect of Leaders’ Pro-social Rule Breaking: Joint Moderating Role of Empowering Leadership and Courage. Front. Psychol. 2019, 9, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenkert, G.G. Innovation, rule breaking and the ethics of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2009, 24, 448–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHart-Davis, L. The unbureaucratic personality. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmann, J. Unbureaucratic Behavior among Street-Level Bureaucrats: The Case of the German State Police. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2017, 37, 430–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, W.; Recker, J.; Kummer, T.F.; Kohlborn, T.; Viaene, S. Constructive deviance as a driver for performance in retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 30, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela-Huotari, K.; Edvardsson, B.; Jonas, J.M.; Sörhammar, D.; Witell, L. Innovation in service ecosystems—Breaking, making, and maintaining institutionalized rules of resource integration. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2964–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, N.; Jamshed, S.; Mustamil, N.M. Striving to restrain employee turnover intention through ethical leadership and pro-social rule breaking. Int. Online J. Educ. Leadersh. 2018, 2, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shum, C.; Ghosh, A.; Gatling, A. Prosocial rule-breaking to help coworker: Nature, causes, and effect on service performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 79, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, D.; Li, N. Sustainable Influence of Manager’s Pro-Social Rule-Breaking Behaviors on Employees’ Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, S.S. White-collar crime: A review of recent developments and promising directions for future research. Annual. Rev. Sociol. 2013, 39, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 79–85, (In Chinese). ISBN 978-7-01-014714-7. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Liang, J.; Chou, L.F.; Cheng, B.S. Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: Research progress and future research directions. In Business Leadership in China: Philosophies, Theories, and Practices; Chen, C.C., Lee, Y.T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 171–205. ISBN 978-0521705431. [Google Scholar]

- Farh, J.L.; Hackett, R.D.; Liang, J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 715–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H. History of Ancient Chinese Thought; SDX Joint Publishing Company: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 281–284, (In Chinese). ISBN 978-7-108-05875-1. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.K. Face and favor: The Chinese power game. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 92, 944–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.K. Self-practice and change of values in Chinese society. In Chinese Values; Yang, K.S., Ed.; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2013; pp. 101–145. ISBN 978-7-300-16548-6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, X.W. Chinese people’s “big justice view” and its social operation mode. Open Times. 2010, 12, 84–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.S.; Chou, L.F.; Farh, J.L. Paternalistic Leadership Scale: The construction and measurement of ternary model. Indigen. Psychol. Res. 2000, 14, 3–64. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M.L. Questionnaire Statistical Analysis Practice—SPSS Operation and Application; Chongqing University Press: Chongqing, China, 2010; ISBN 978-7-5624-5088-7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: A comment. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Harrison, S.H.; Corley, K.G. Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 325–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.S.; Park, T.Y.; Koo, B. Identifying organizational identification as a basis for attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 1049–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reade, C. Antecedents of organizational identification in multinational corporations: Fostering psychological attachment to the local subsidiary and the global organization. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2001, 12, 1269–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suifan, T.S.; Diab, H.; Alhyari, S.; Sweis, R.J. Does ethical leadership reduce turnover intention? The mediating effects of psychological empowerment and organizational identification. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2020, 30, 410–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.M.; Sitkin, S.B.; Burt, R.S.; Camerer, C. Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.M.; Peng, A.C.; Hannah, S.T. Developing trust with peers and leaders: Impacts on organizational identification and performance during entry. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1148–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R.; Lind, E.A. A relational model of authority in groups. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 25, 115–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, S.J.; Shore, L.M.; Liden, R.C. Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Hannah, S.T.; Gok, K.; Arslan, A.; Capar, N. The moderated influence of ethical leadership, via meaningful work, on followers’ engagement, organizational identification, and envy. J. Bus. Ethics. 2017, 145, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Mayer, D.M.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Workman, K.; Christensen, A.L. Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 115, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alchian, A.A.; Demsetz, H. Production, information costs, and economic organization. Am. Econ. Rev. 1972, 62, 777–795. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, E.A.; Van den Bos, K. When fairness works: Toward a general theory of uncertainty management. Res. Organ. Behav. 2002, 24, 181–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, T.R. The Psychology of Procedural Justice: A Test of the Group-value Model. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 830–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leventhal, G.S. What should be done with Equity Theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In Social Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research; Gergen, K.J., Greenberg, M.S., Willis, R.H., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 27–55. ISBN 978-1-4613-3089-9. [Google Scholar]

- Arend, R.J. Entrepreneurs as Sophisticated Iconoclasts: Rational Rule-Breaking in an Experimental Game. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baucus, M.S.; Norton, W.I.; Baucus, D.A.; Human, S.E. Fostering creativity and innovation without encouraging unethical behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soenen, G.; Melkonian, T. Fairness and commitment to change in M&As: The mediating role of organizational identification. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 486–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Li, C.; Wu, K.; Long, L. Procedural justice and voice: A group engagement model. J. Manag. Psychol. 2019, 34, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blader, S.L.; Tyler, T.R. Testing and extending the group engagement model: Linkages between social identity, procedural justice, economic outcomes, and extra-role behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erat, S.; Kitapçı, H.; Akçin, K. Managerial Perception and Organizational Identity: A Comparative Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mael, F.A.; Ashforth, B.E. Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. J. Organ. Behav. 1992, 13, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehoff, B.P.; Moorman, R.H. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organizational citizenship behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 1993, 36, 527–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-60918-230-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.J.; Demerouti, E.; Le Blanc, P. Transformational leadership, adaptability, and job crafting: The moderating role of organizational identification. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, T. Doing good is not enough, you should have been authentic: Organizational identification, authentic leadership and CSR. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).