Touching Down in Cities: Territorial Planning Instruments as Vehicles for the Implementation of SDG Strategies in Cities of the Global South

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Planning Instruments as Vehicles for the Implementation of SDGs

2. Materials and Methods

3. Territorial Planning Instruments in Local Legislation

“In 2030, Medellin will have a well-balanced territorial system for human beings: culturally rich and diverse, and ecologically, spatially and functionally integrated to the national, regional and metropolitan Public and Collective System. This will contribute to the consolidation of a region of cities, where social and collective rights are wholly exercised, landscapes and geographies are valued, and competitiveness and rural development are promoted. All this in order to leave future generations a territory that is socially inclusive, globally connected and environmentally sustainable, with economic development strategies that fit regional and metropolitan contexts”.[36] (p. 6)

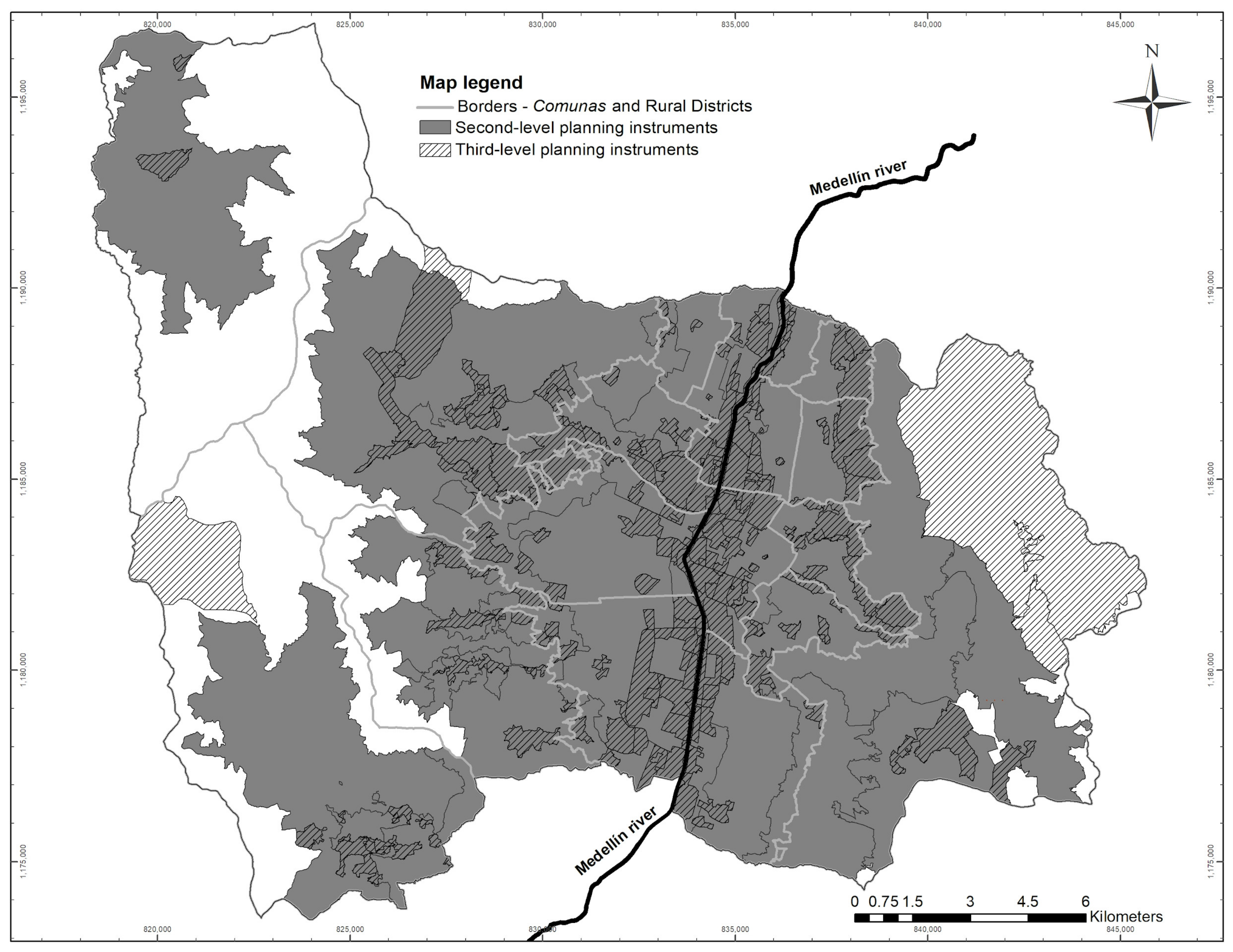

3.1. Second-Level Planning Instruments

- The riverbanks, which represent the greatest urban transformation potential, considering that they currently host industrial facilities, and have thus low residential occupancy and inefficient use of valuable urban land.

- The basins of two important creeks that flow into the Medellin river (Santa Elena from the east, La Iguaná from the west) and encompass a portion of the hillsides (both on urban and rural land). These require planning interventions, mainly due to the growth of informal settlements in those directions.

- Finally, the limits between urban and rural land, which require interventions to plan and orient the city’s growth and expansion.

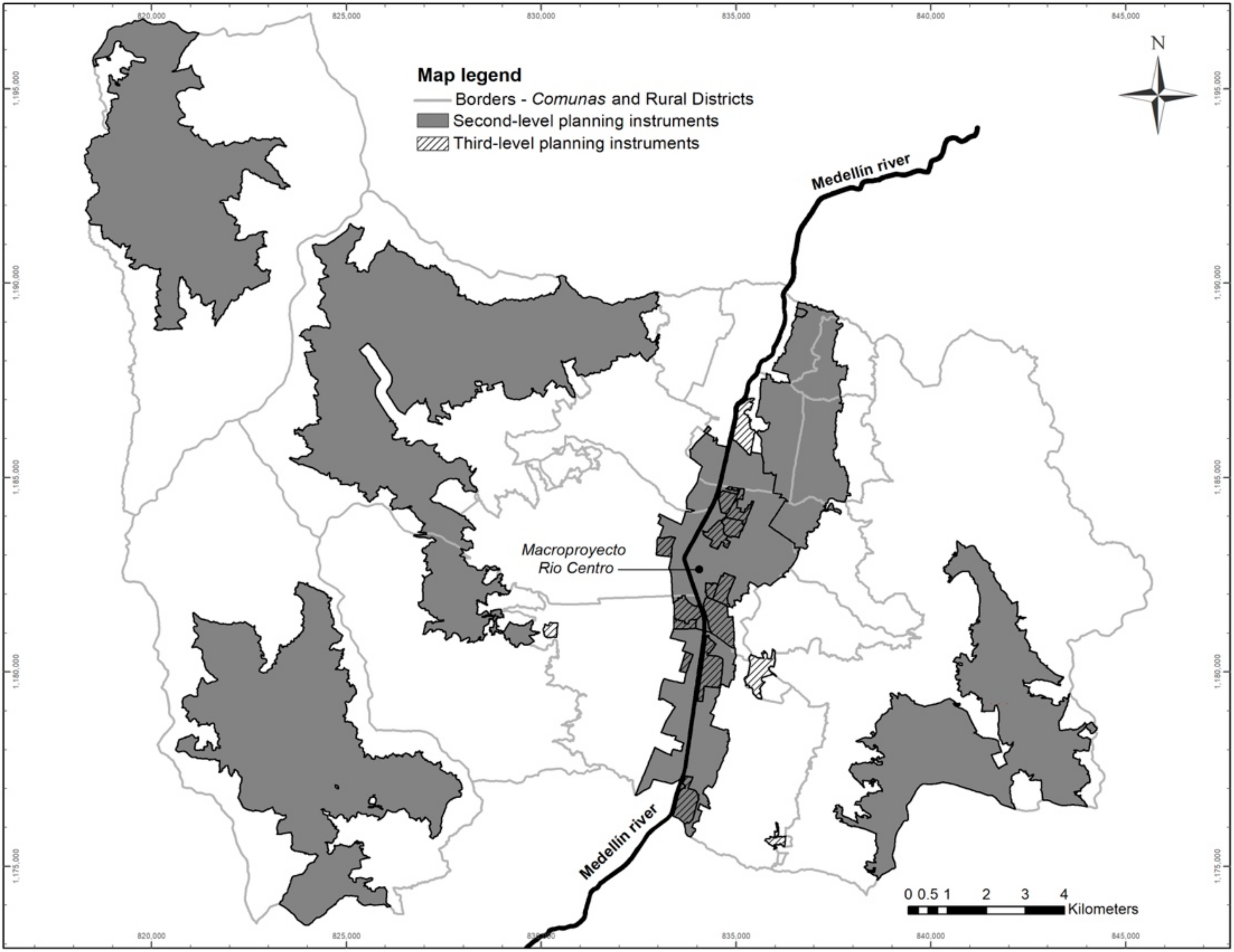

3.2. Third-Level Instruments

- Planes Parciales (PP), which are applied to areas that need to be renewed in their entirety, due to physical and social deterioration. They also apply to what is termed expansion land, i.e., areas towards which the city is expected to grow.

- Urbanistic Legalization and Regularization Plans (PLRU), which are instruments that allow interventions in areas that require comprehensive improvements, due to the presence of informal settlements that lack adequate infrastructure to guarantee decent living conditions for their inhabitants.

- Planes Maestros (PM), which are instruments oriented towards consolidating the ordering of areas with high concentrations of public amenities, public spaces, and environmentally-important sites.

- Rural Planning Units (UPR), which encompass rural areas with complex historical development that require articulated interventions in order to guarantee territorial planning in the middle and long run.

- Special Management Plans for the Protection of Heritage (PEMP), which are planning instruments that address areas that require the conservation of infrastructure classified as heritage.

3.3. The Adoption Process

3.4. Other Relevant Territorial Development Instruments for the Concretion of SDGs

4. Results

4.1. National and Local Strategies for the Implementation of SDGs

“even if SDGs pursue global objectives, their achievement depends on the ability to materialize them in cities, regions and municipalities. It is at this scale that goals and targets, and implementation means must be defined, as well as the use of indicators to define baselines and monitor their progress”.[39] (p. 43)

4.2. Municipal Development Plans (MDPs)

“[…] is not an issue that can be addressed in one way, it is [diverse] and complex. It is necessary to recover [people’s] confidence in local participation mechanisms, institutionalize processes and rules in the search of a stable peace that makes it possible to overcome the use of violence as a means to solve conflicts, promote social dialogue and sustainable economic and social development alternatives”.(p. 164) [41]

- Economic reactivation and the software valley—SDGs #8, #9, and #10.

- Educational and cultural transformation—SDGs #1, #2, and #4.

- Medellín me cuida (health and human rights)—SDGs #1, #2, #3, #5, #10, and #16.

- Ecocity—SDGs #6, #7, #11, #12, #13, and #15.

- Governance and governability—SDG #17.

4.3. Local Development Plans (LDPs)

4.4. Second and Third-Level Territorial Planning Instruments

5. Discussion

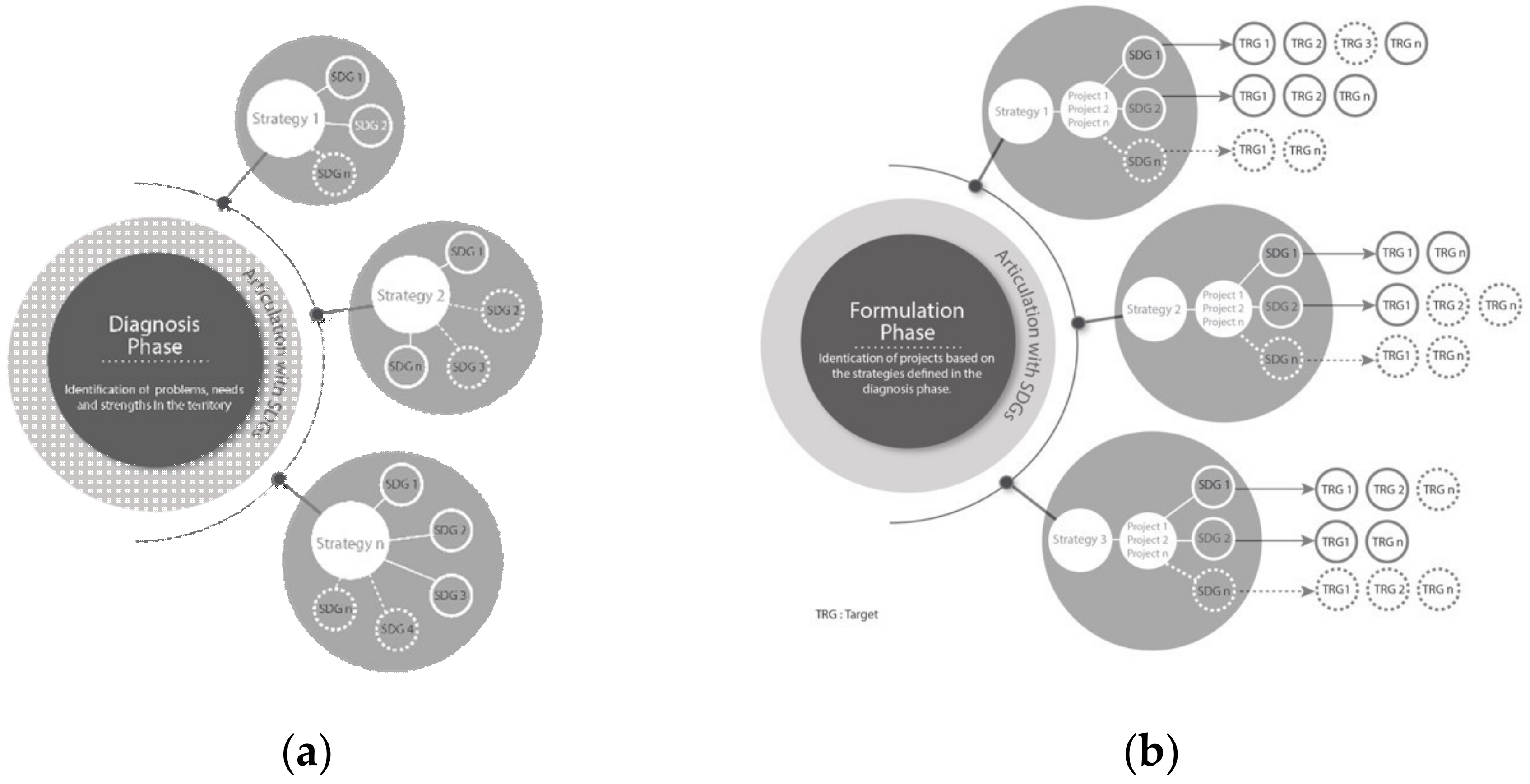

- The diagnosis phase—Based on the identification of needs, strengths, and problems of different types (e.g. related to housing, utilities, public space, mobility, and the environment), the resulting study (called Diagnosis Technical Support Document) must define strategies to address them. These strategies are today not explicitly linked to sustainable development agendas, as it was shown in the results. For future studies, the elaborating team can explicitly identify which SDGs are impacted by each strategy and how.

- The formulation phase—This process’s deliverable is a Formulation Technical Support Document, which, in turn, leads to the issuing of an administrative act (e.g., a decree, an agreement, or a resolution). Based on the strategies discussed during the diagnosis phase, the formulation team can define specific projects for each one of them. Up to this point, strategies will already be linked to SDGs. The team can continue further and identify the project’s contribution to the level of targets. Such contribution can be direct or indirect, and the team must justify this relation. This analysis is highly important: infrastructure alone, according to [24], has a direct or indirect influence on 72% of SDG targets. The team has to base its analysis on Medellin Agenda 2030, which already identified which targets apply to the city’s context.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnett, C.; Parnell, S. Ideas, implementation and indicators: Epistemologies of the post-2015 urban agenda. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, P.; Gustafsson, S. Moving from high-level words to local action—Governance for urban sustainability in municipalities. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Dugand, S. The evolution of sweden’s urban sustainability marketing tool: A comparative study of two major international events. J. Urban. Technol. 2016, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuleman, L.; Niestroy, I. Common but differentiated governance: A metagovernance approach to make the SDGs work. Sustainability 2015, 7, 12295–12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, C.; Garcia-Martin, M.; Raymond, C.M.; Shaw, B.J.; Plieninger, T. The potential for integrated landscape management to fulfil Europe’s commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2018, 177, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Dugand, S.; Hjelm, O.; Baas, L.; Ríos, R.A. Lessons from the spread of bus rapid transit in Latin America. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansard, J.S.; Pattberg, P.; Widerberg, O. Cities to the rescue? Assessing the performance of transnational municipal networks in global climate governance. Int Environ Agreem P 2016, 17, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D.; Shiroyama, H. The challenge of sustainable urban development and transforming cities. In Governance of Urban Sustainability Transitions. European and Asian Experiences; Loorbach, D., Wittmayer, J.M., Shiroyama, H., Fujino, J., Mizuguchi, S., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, S. Defining a global urban development agenda. World Dev. 2016, 78, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D.; Hosseini, M.; Kennedy, C.; Behdadi, A. An urban approach to planetary boundaries. Ambio 2016, 45, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2016. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- United Nations (UN). New Urban Agenda. 2017. Available online: http://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Klopp, J.M.; Petretta, D.L. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities 2017, 63, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metternicht, G. Land Use and Spatial Planning – Enabling Sustainable Management of Land Resources; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.C.L.; Smart, J.C.R.; Davey, P. Can learned experiences accelerate the implementation of sustainable development goal 11? A framework to evaluate the contributions of local sustainable initiatives to delivery SDG 11 in Brazilian municipalities. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, A.; Brebbia, C.A. Localising global goals in Australia’s global city: Sydney. WIT Trans. Ecol. Envir. 2017, 226, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, P.; Dávila, J.D. Mobility innovation at the urban margins—Medellín’s Metrocables. City 2011, 15, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tomás Medina, C. Urban regeneration of Medellín. An example of sustainability. UPLanD 2018, 3, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, I.D.; Ortiz, C. Medellín in the headlines: The role of the media in the dissemination of urban models. Cities 2020, 96, 102431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stienen, A. Urban technology, conflict education, and disputed space. J. Urban. Technol. 2009, 16, 109–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, F.; Cruz, T. Global justice at the municipal scale: The case of Medellín, Colombia. In Institutional Cosmopolitanism; Cabrera, L., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 189–215. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial Planning. 2015. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/IG-UTP_English.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Medellín Cómo Vamos. Servicios Públicos en Medellín [Public Utilities in Medellín]. 2018. Available online: https://www.medellincomovamos.org/servicios-publicos-en-medellin (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Adshead, D.; Thacker, S.; Fuldauer, L.I.; Hall, J.W. Delivering on the sustainable development goals through long-term infrastructure planning. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Ferrari, S.; Smith, H.C.; Coupe, F.; Rivera, H. City profile: Medellin. Cities 2018, 74, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotomayor, L.; Information, R. Equitable planning through territories of exception: The contours of Medellin’s urban development projects. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2015, 37, 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M.; Morenoff, J.D.; Hansen, B.B.; Hicks, K.J.T.; Duque, L.F.; Restrepo, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V. Reducing violence by transforming neighborhoods: A natural experiment in Medellin, Colombia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2012, 175, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culwick, C.; Washbourne, C.L.; Anderson, P.M.; Cartwright, A.; Patel, Z.; Smit, W. CityLab reflections and evolutions: Nurturing knowledge and learning for urban sustainability through co-production experimentation. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPAL. Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible [Sustainable Development Goals]. Available online: https://observatorioplanificacion.cepal.org/es/sdgs (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Franz, T. Urban governance and economic development in Medellín: An “urban miracle”? Lat. Am. Perspect. 2017, 44, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, A. In Medellin, Cable Cars Transformed Slums—In Rio, They Made Them Worse. 2018. Available online: https://apolitical.co/en/solution_article/medellin-cable-cars-transformed-slums-rio-made-worse (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- UCLG. The Localization of the Global Agendas. How Local Action is Transforming Territories and Communities. Fifth Global Report on Decentralization and Local Democracy; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research—Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Congreso de la República de Colombia. Ley 388. 1997. Available online: http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley_0388_1997.html (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Concejo de Medellín. Acuerdo Nº 48. 2014. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/irj/go/km/docs/pccdesign/SubportaldelCiudadano_2/PlandeDesarrollo_0_17/ProgramasyProyectos/Shared%20Content/Documentos/2014/POT/ACUERDO%20POT-19-12-2014.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- TRENDS. Localizing the SDGs in Colombian cities through the Cómo Vamos City Network. 2019. Available online: https://www.sdsntrends.org/research/2019/4/15/local-data-action-colombia (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Observatorio de Políticas Públicas del Concejo de Medellín (OPPCM). Planes de Desarrollo Local y su relación con el Sistema Municipal de Planeación [Local Development Plans and their relation with the Municipal Planning System]. 2017. Available online: http://www.eafit.edu.co/centros/analisis-politico/publicaciones/observatorio/Documents/investigacion-planes-de-desarrollo-local.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación (DNP). Documento CONPES 3918 – Estrategia para la implementación de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS) en Colombia [Strategy for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in Colombia]. 2018. Available online: https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Conpes/Econ%C3%B3micos/3918.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Departamento Administrativo de Planeación del Municipio de Medellín (DAP). Documento COMPES Nº 1—Definición de Metas y Estrategias Para el Seguimiento Y Evaluación de la Agenda de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible -ODS- 2030 de Medellín [Definition of Targets and Strategies for The Follow-Up And Evaluation of Medellin’s Sustainable Development Goals -SDG- Agenda 2030]; Departamento Administrativo de Planeación: Medellín, Colombia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Concejo de Medellín. Acuerdo Nº 003. 2016. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/normograma/docs/a_conmed_0003_2016.htm (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- UNDP; GTF; UCLG; UN-Habitat; Diputació Barcelona. Learning Module 2: Territorial Planning to Achieve the SDGs. 2019. Available online: https://www.uclg.org/sites/default/files/module_2_territorial_planning.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Concejo de Medellín. Proyecto de acuerdo Plan de Desarrollo Medellín Futuro 2020–2023 [Agreement Project Development Plan Medellin Futuro 2020–2023]. 2020. Available online: http://www.concejodemedellin.gov.co/es/plan-de-desarrollo-2020-2023?language_content_entity=es (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Quintero, D. Anteproyecto plan de desarrollo Medellín Futuro 2020-2023 [Draft Development Plan Medellin Futuro 2020–2023]. 2020. Available online: http://www.concejodemedellin.gov.co/es/plan-de-desarrollo-2020-2023?language_content_entity=es (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Alcaldía de Medellín. Plan de Desarrollo Local—Actualización. Comuna 3 Manrique [Local Development Plan—Update. Comuna 3 Manrique]. 2019. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/nuestrodesarrollow/actualizacion-de-los-planes-de-desarrollo-local/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- Alcaldía de Medellín. Plan de Desarrollo Local—Actualización. Comuna 13 San Javier [Local Development Plan—Update. Comuna 13 San Javier]. 2019. Available online: https://www.medellin.gov.co/nuestrodesarrollow/actualizacion-de-los-planes-de-desarrollo-local/ (accessed on 18 August 2020).

- ONU-Habitat; INFONAVIT. Vivienda y ODS en México [Housing and SDGs in Mexico]. 2018. Available online: http://70.35.196.242/onuhabitatmexico/VIVIENDA_Y_ODS.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2020).

| Level | Name | Area/Geography | Discusses SDGs | Findings | Discusses Sustainable Development | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | Municipal Development Plan (2016-2019) | City | - | Yes | SDGs are highlighted as an important input for the plan. SDG symbols are used in connection to strategic lines (with the exception of 2, 10 and 14), but only SDGs 2, 5 and 11 are mentioned in the text (although there is no important discussion about their relevance). There is no connection to second or third-level planning instruments. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development and discussion of second and third-level planning instruments such as Macroproyectos, Planes Parciales, Planes Maestros, PLRU, UPR and PEMPP. |

| N/A | Municipal Development Plan (2020-2023) | City | - | Yes | All SDGs identified by Agenda Medellin 2030 are discussed in the document in connection to the plan’s strategic lines. Rural Farming Districts (second level) is discussed for the achievement of SDG 2. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development and some discussions about second and third-level planning instruments. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 3 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. Mentions workshop to identify the LDP’s contribution to SDGs, but no information about its results. Agenda 2030 used as a reference. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. No discussion of second and third-level planning instruments. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 8 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. No discussion of second and third-level planning instruments. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 9 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. Mentions a workshop to identify the LDP’s contribution to SDGs, but no information about its results. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. No discussion of second and third-level planning instruments. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 12 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. Mentions a workshop to identify the LDP’s contribution to SDGs, but no information about its results. Agenda 2030 used as a reference. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. No discussion of second and third-level planning instruments. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 13 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. Highlights the need to articulate LDP to the master plan and international agendas such as the SDG’s. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. No discussion of second and third-level planning instruments. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 16 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. Discussion of the impact of one third-level instrument (i.e., Plan Parcial) on public space and ammenities. |

| N/A | Local Development Plan | Comuna 90 | - | Yes | Standard introduction mentioning SDGs. Mentions a workshop to identify the LDP’s contribution to SDGs, but no information about its results. Agenda 2030 used as a reference. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable development. No discussion of second and third-level planning instruments. |

| Second | Rural District | All five Rural Districts | Formulation | Yes | Mentions alignment with rural development, ending poverty and reducing inequalities. Also, the adoption of an index said to be "directly related" to SDGs. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable rural development, such as "sustainable agriculture," "sustainable practices," "sustainable production," "sustainable use," "sustainable territory," "sustainable management," "sustainable life projects for the youth" and "sustainable tourism." |

| Resolution | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Wide use of expressions related to sustainable rural development. | |||

| DTS1 | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Some use of expressions related to sustainable rural development. | |||

| DTS2 | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Some use of expressions related to sustainable rural development. | |||

| DTS3 | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Some use of expressions related to sustainable rural development. | |||

| Macroproyecto | Río Centro | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | |

| PUIAL | Northeast | Formulation | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |

| Resolution | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | |||

| Third | Plan Maestro | Cerro Nutibara | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. |

| Zoo | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | ||

| UdeM | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | ||

| Plan Parcial | Moravia | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |

| DTS Diagnosis | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | |||

| DTS Formulation | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Some use of expressions related to sustainable territorial development. | |||

| La Cumbre | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | ||

| DTS | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |||

| Villa Carlota | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | ||

| DTS | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |||

| Santa María de los Ángeles | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | ||

| DTS | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |||

| Naranjal 1 | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | ||

| DTS | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |||

| Naranjal 2 | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | ||

| Asomadera | Decree | No | No mention of SDGs. | No | No mention of sustainable development. | ||

| DTS | No | No mention of SDGs. | Yes | Loose mention of sustainable development. | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mejía-Dugand, S.; Pizano-Castillo, M. Touching Down in Cities: Territorial Planning Instruments as Vehicles for the Implementation of SDG Strategies in Cities of the Global South. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176778

Mejía-Dugand S, Pizano-Castillo M. Touching Down in Cities: Territorial Planning Instruments as Vehicles for the Implementation of SDG Strategies in Cities of the Global South. Sustainability. 2020; 12(17):6778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176778

Chicago/Turabian StyleMejía-Dugand, Santiago, and Marcela Pizano-Castillo. 2020. "Touching Down in Cities: Territorial Planning Instruments as Vehicles for the Implementation of SDG Strategies in Cities of the Global South" Sustainability 12, no. 17: 6778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176778

APA StyleMejía-Dugand, S., & Pizano-Castillo, M. (2020). Touching Down in Cities: Territorial Planning Instruments as Vehicles for the Implementation of SDG Strategies in Cities of the Global South. Sustainability, 12(17), 6778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12176778