Relational and Logistical Dimensions of Agricultural Food Recovery: Evidence from California Growers and Recovery Organizations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Logistical Challenges: Highly Specific and Variable

How do you have a marketing plan for something you don’t even know you’re going to have? And you don’t know when it’s going to appear. And how are you going to get your ten people on that assembly line, all of a sudden, when they call you that once every other year, or twice, when you get a load rejected?

The way they harvest it is like a lawnmower. They go across and it just clips and collects the spinach, and when that happens a lot of smaller spinach sprouts get their tips cut off. We said, “Well, there is so much spinach that’s still in the field after that first harvest, if you let it grow a little bit longer it will be just the size that we would use. We’ll pay the same price we would pay for our existing spinach that we buy from you now.” It was still not preferable or financially viable: The extra effort of having this sort of funky field that does things differently was a big ask for them. And they would have to do a specific run of that spinach because it has to be separated out.

We can harvest loads of tomatoes in 15 minutes. If I had to have something alongside there that was capturing the green ones; and it took me, instead of 15 minutes, 20 minutes to pick a load; I don’t think it would be worth doing it. Plus, you’d have more machinery running alongside the harvester, which adds to worker safety and lots of issues like that.

4.2. Relational Work: Learning from Success and Failure

4.2.1. Establishing Recovery Partnerships

Practical and Cultural Impediments to Building a Relationship

We have people come through from all over the world and they go, “Wow, why are you throwing this away or why are you throwing that away?” We’re like, “We wish the hell we weren’t.” And they’re going, “We’re going to figure this out.” And we go, “Okay, get back to us, yeah.”

There was a video of all the tomatoes being dumped last year – some local news report – and they had someone from a food bank complaining. Saying “What a waste, they should never throw this stuff away.” He was shaming, but you’ve got to build relationships instead of sitting there saying just “tsk, tsk, tsk.”

I have a bit of an issue with this idea of food loss. I have been in the leafy greens business forever. I have done a ton of tours. They go out there and go, “Oh my god, I can’t believe there is so much waste!” And I’m going, “Waste? What are you talking about? We just got the maximum yield here!” So, we are worlds apart. People don’t understand that the outer leaves are the old, cruddy leaves, and that what they are eating is the younger, good stuff. You wouldn’t go out into a tomato field and see all of those vines and go, “oh, what a waste!” It’s not waste. It’s what we needed to grow the vegetable!

Crafting Initial Approaches and Messages Carefully

At the beginning, it was very hard to get anybody to take us seriously because farmers are so used to being promised the world and then nothing coming back or being taken advantage of. What I found is I could not do it over the telephone or email. What I needed to do was actually go sit down with them, because the inspiration comes through. They hear that I know what I’m talking about and then if there’s enough time and personal contact we can drop deeper and deeper until they recognize that we really have something to offer them.

I was getting these appointments to speak in front of boards, and folks really expected to listen politely and pat me on the head and send me on my way. Generally, the audience is a bunch of farmers on their phones. But my pitch is, I’m not here to tell you people are hungry, or to tell you how to do your business, but I’m here to say that there is a way to donate your excess and increase your prosperity at the same time. We want to be integral to your business model. And then you watch the phones go down, and people pay attention.

Drawing on a Common Identity or History

We went around, and we passed out flyers. We went to different farms. We Googled some farmers. We actually reached a few on Facebook as well. So we tried to reach them through every avenue that we saw. Most of them we got through the farmer who is on our Board. He called them, and they told him yes. And then when I contacted them, it was kind of like, “Hey, I don’t have time for this.” It’s difficult. It is a type of a good ol’ boy network.

Focusing on Each Party’s Interests to Identify Potential Mutual Benefits

[She] talked her way past our shipping department and got me and then said, “can I just walk through?” And then she pointed and just said, “where does this go, where does this go?” When I said this goes to goats, she said, “we’ll take it.” And that started the relationship of realizing what they could take. We didn’t know how much they could take.... Now we load sometimes five or six semi-trucks a week to them of product that we were just disking into the ground.… Some [peppers] make it past the initial sort and they get that little sticker for the grocery store applied to them, and the processor won’t take those. We didn’t have a place to go with them, so they would just go into a trash bin, or to like, a swap meet. [The food bank] is like, “can we have these? It saves us time and energy.

4.2.2. Sustaining Recovery Partnerships

Communication to Facilitate Collaborative Problem-Solving

Because of our scale, we’ve been able to develop programs with farms where they’re going out and doing a second harvest for a certain grade of field packed produce or setting up lines in their operations. It’s just proving to them that there is going to be just enough demand on our side to make that investment worth it. We often work with them to help them set those processes up because there’s the upfront cost, but then once they’ve trained those pickers, they’re able to see the returns over time.

I worked on the logistics. For instance, I sold the food bank a bunch of totes. I told them, “This the way to do this. Don’t do this in cartons.” Then we worked a deal with the cooler, where they donated the cooling, because I’m a partner in a cooler. It stays there for the week, and then they can efficiently send a six-pallet truck over, pick it up, and they don’t get inundated with, “Here comes two loads of product.” You know what’s coming, and they can do it in a system.

So our number-one top donor is a local CSA farmer. He has twice-weekly pick-ups, so we go and glean whatever is left over the day after his pick-ups. So that works very well for us because it’s very predictable. He also is really communicative. If there for some reason is not a lot leftover, he will reach out and say, “Hey, there’s only one box of lettuce this week, and it might not be worth the resources that it would cost you guys to drive out here.”

Flexibility and Consistency

When you develop relationships with customers, they will help you, you know. When you’re short you don’t just cut them out. You cut everybody back some. Or if you’re long, you encourage them. “Hey, John, I really need you to take an extra pallet today,” or, you know, “let’s lower the price a little bit so you can work it out.”

They’re dealing 23 and a half hours a day with exceptions. They want a half-hour where they don’t have to deal with an exception. … You’re going to be here on Wednesday morning at nine to pick this product up, as opposed to, “Well I’ll be there on Wednesday except maybe if some volunteer doesn’t make it in,” or whatever it is.... What are ways that I can bring value to the relationship?” It doesn’t necessarily have to be money every time. It can be consistency.

I’ve gone around and around with foodservice people, and the schools, and they said, we’re happy to buy your stuff, but you have to have consistency. You have to be able to supply us 52 weeks out of the year. You have to have it prepared, cleaned, ready to go, so that our food servers can take it out of a bag, pour it out, for the kids to take. And we want it competitively priced. And I said I can’t do any of that. So, there we are, at the same stalemate for years.

When [the juicing company] take[s] the culls away from us, it simplifies their life if they have a minimum stop time. They go where they’re going to get good service. Timely. And where there’s enough volume to load their trucks. They don’t want to be running around. Through the years, we’ve been able to adapt. When he shows up, boom, boom. So, it’s not just the fruit they’re coming for, they’re also coming for the service.

I might say, “This time let’s move the trash for them, and then we’ll educate them.” If they’re a new donor we’ll educate them on what our guidelines are, invite them to take a tour of our warehouse, talk to them about it a little bit and then try again. Because that might be an opportunity for more in the future.

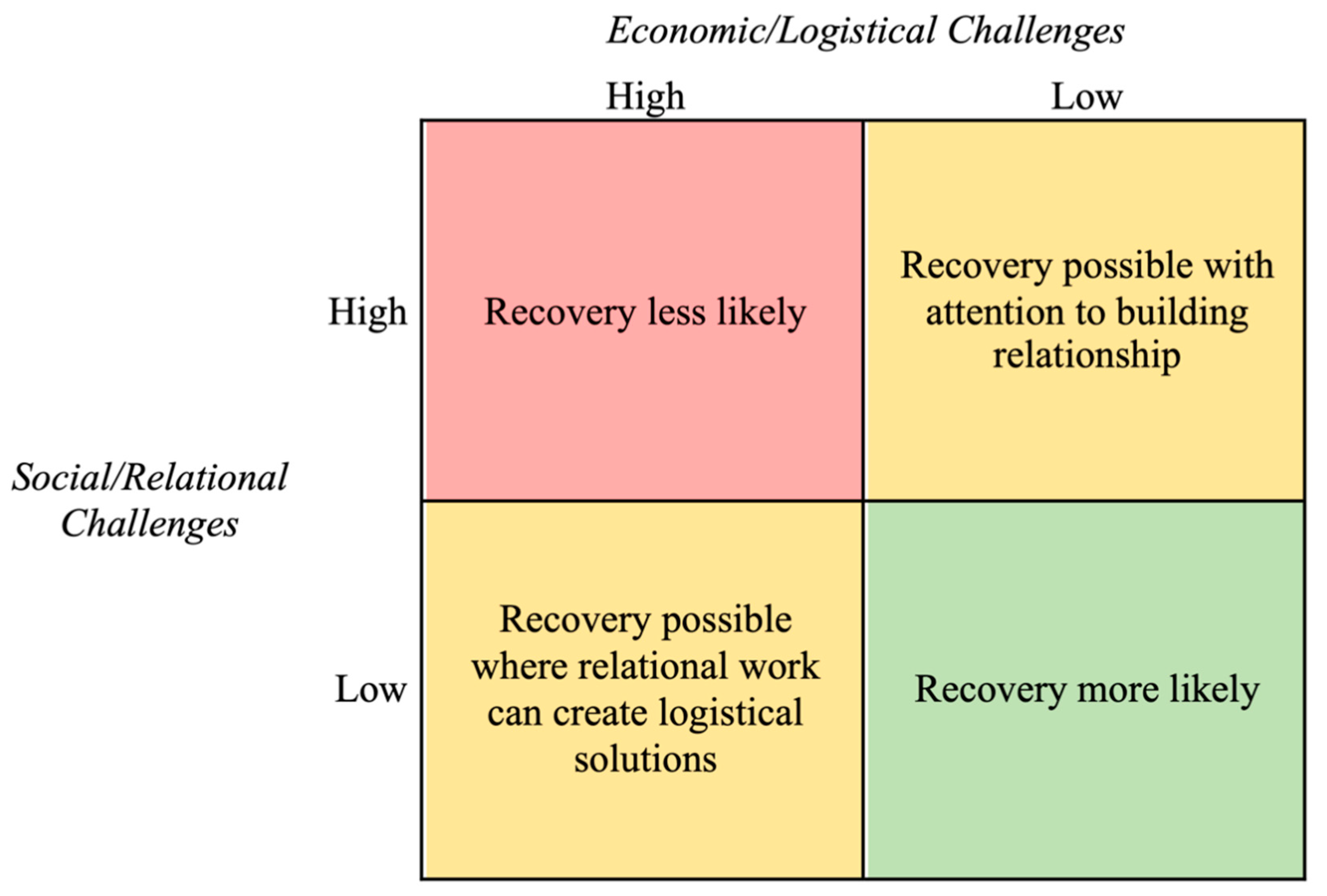

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; van Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes, and Prevention; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/mb060e/mb060e00.htm (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Johnson, L.K.; Dunning, R.D.; Bloom, J.D.; Gunter, C.C.; Boyette, M.D.; Creamer, N.G. Estimating on-farm food loss at the field level: A methodology and applied case study on a North Carolina farm. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 137, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.K.; Dunning, R.D.; Gunter, C.C.; Dara Bloom, J.; Boyette, M.D.; Creamer, N.G. Field measurement in vegetable crops indicates need for reevaluation of on-farm food loss estimates in North America. Agric. Syst. 2018, 167, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Sobal, J.; Lyson, T.A. An analysis of a community food waste stream. Agric. Hum. Values 2009, 26, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spang, E.S.; Achmon, Y.; Donis-Gonzalez, I.; Gosliner, W.A.; Jablonski-Sheffield, M.P.; Abdul Momin, M.; Moreno, L.C.; Pace, S.A.; Quested, T.E.; Winans, K.S.; et al. Food Loss and Waste: Measurement, Drivers, and Solutions. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2019, 44, 13.1–13.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcuri, S. Food poverty, food waste and the consensus frame on charitable food redistribution in Italy. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, F.; Cavicchi, A.; Brunori, G. Food waste reduction and food poverty alleviation: A system dynamics conceptual model. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Sönmez, E.; Gómez, M.I.; Fan, X. Combining two wrongs to make two rights: Mitigating food insecurity and food waste through gleaning operations. Food Policy 2017, 68, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A. Opening the black box of food waste reduction. Food Policy 2014, 46, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourad, M. Recycling, recovering and preventing “food waste”: Competing solutions for food systems sustainability in the United States and France. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 126, 461–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkenkamp, J.; Nennich, T. Beyond Beauty: The Opportunities and Challenges of Cosmetically Imperfect Produce, Report No. 2: Interview Findings with Minnesota Produce Growers; Tomorrow’s Table: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015; Available online: http://ngfn.org/resources/ngfn-database/knowledge/Beyond%20Beauty%20farm%20interview%20report%20J%20Berkenkamp%2010-21-15.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Berkenkamp, J.; Nennich, T. Beyond Beauty: The Opportunities and Challenges of Cosmetically Imperfect Produce, Report No. 1: Survey Results from Minnesota Produce Growers; Tomorrow’s Table: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015; Available online: http://ngfn.org/resources/ngfn-database/Beyond_Beauty_Grower_Survey_Results_052615.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- ReFED. A Roadmap to Reduce U.S. Food Waste By 20 Percent; Rethink Food Waste Through Economics and Data; 2016; Available online: https://www.refed.com/downloads/ReFED_Report_2016.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Berkenkamp, J.; Meehan, M. Beyond Beauty: The Opportunities and Challenges of Cosmetically Imperfect Produce, Report No. 4: Hunger Relief Report; Tomorrow’s Table: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016; Available online: http://ngfn.org/resources/ngfn-database/Beyond%20Beauty%20-%20Hunger%20Relief%20Report.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Vitiello, D.; Grisso, J.A.; Whiteside, K.L.; Fischman, R. From commodity surplus to food justice: Food banks and local agriculture in the United States. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig-Ohm, S.; Dirksmeyer, W.; Klockgether, K. Approaches to Reduce Food Losses in German Fruit and Vegetable Production. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, A.; Campbell, D.C.; Spang, E.S. Does on-farm food loss prevent waste? Insights from California produce growers. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.K.; Bloom, J.D.; Dunning, R.D.; Gunter, C.C.; Boyette, M.D.; Creamer, N.G. Farmer harvest decisions and vegetable loss in primary production. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milepost Consulting Left-Out: An Investigation of the Causes & Quantities of Crop Shrink; Natural Resources Defense Council. 2012. Available online: https://www.nrdc.org/resources/left-out-investigation-causes-quantities-crop-shrink (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Pellegrini, G.; Annosi, M.C.; Contò, F.; Fiore, M. What Are the Conflicting Tensions in an Italian Cooperative and How Do Members Manage Them? Business Goals’, Integrated Management, and Reduction of Waste within a Fruit and Vegetables Supply Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausang, C.; Hall, C.; Toma, L. Food waste and losses in primary production: Qualitative insights from horticulture. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 126, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.D.; Reay, D.S.; Bomberg, E.; Higgins, P. Avoidable food losses and associated production-phase greenhouse gas emissions arising from application of cosmetic standards to fresh fruit and vegetables in Europe and the UK. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bemmel, A.; Parizeau, K. Is it food or is it waste? The materiality and relational agency of food waste across the value chain. J. Cult. Econ. 2019, 13, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunders, D. Wasted: How America is Losing Up to 40 Percent of Its Food from Farm to Fork to Landfill; Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). 2012. Available online: https://www.nrdc:resources/wasted-how-america-losing-40-percent-its-food-farm-fork-landfill (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Eriksson, M.; Ghosh, R.; Mattsson, L.; Ismatov, A. Take-back agreements in the perspective of food waste generation at the supplier-retailer interface. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gille, Z. From risk to waste: Global food waste regimes. Sociol. Rev. 2012, 60, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.A.; Gray, L.C.; Harwood, M.J.; Osland, T.J.; Tooley, J.B.C. On-farm food loss in northern and central California: Results of field survey measurements. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 149, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Werf, P.; Gilliland, J.A. A systematic review of food losses and food waste generation in developed countries. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Waste Resour. Manag. 2017, 170, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.R.; Chen, R.J.C. Using Two Government Food Waste Recognition Programs to Understand Current Reducing Food Loss and Waste Activities in the U.S. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, A.A.; Neff, R.A. Food Rescue Intervention Evaluations: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerghi, C.; McKay, F.H.; Dunn, M. The Role of Food Banks in Addressing Food Insecurity: A Systematic Review. J. Community Health 2016, 41, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, R.A.; Kanter, R.; Vandevijvere, S. Reducing Food Loss And Waste While Improving The Public’s Health. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1821–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoisington, A.; Butkus, S.N.; Garrett, S.; Beerman, K. Field Gleaning as a Tool for Addressing Food Security at the Local Level: Case Study. J. Nutr. Educ. 2001, 33, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, E.; Lee, D.; Gómez, M.I.; Fan, X. Improving Food Bank Gleaning Operations: An Application in New York State. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 98, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, L.; Tougas, D.; Rondeau, K.; Mah, C.L. “In”-sights about food banks from a critical interpretive synthesis of the academic literature. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppendieck, J. Sweet Charity? Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement; Penguin Putnam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasuk, V.; Eakin, J.M. Food assistance through “surplus” food: Insights from an ethnographic study of food bank work. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshawsky, D.N. The devolution of urban food waste governance: Case study of food rescue in Los Angeles. Cities 2015, 49, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riches, G. Thinking and acting outside the charitable food box: Hunger and the right to food in rich societies. Dev. Pract. 2011, 21, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikka, V. Charitable food aid in Finland: From a social issue to an environmental solution. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucknum, M.; Bentzel, D. Food Banks as Local Food Champions: How Hunger Relief Agencies Invest in Local and Regional Food Systems. In Institutions as Conscious Food Consumers; Thottathil, S.E., Goger, A.M., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 285–305. ISBN 978-0-12-813617-1. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, J.L. The logics of surplus food redistribution. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 1872–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramanti, V.; Coeli, A.; Ferri, L.; Fiorentini, G.; Ricciuti, E. A Model for Analysing Non-profit Organisations in the Food Recovery, Management and Redistribution Chain. In Foodsaving in Europe: At the Crossroad of Social Innovation; Baglioni, S., Calò, F., Garrone, P., Molteni, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 99–130. ISBN 978-3-319-56555-2. [Google Scholar]

- Adamashvili, N.; Chiara, F.; Fiore, M. Food Loss and Waste, a global responsibility?! Econ. Agro-Aliment. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.C.; Ross, M.; Webb, K.L. Improving the Nutritional Quality of Emergency Food: A Study of Food Bank Organizational Culture, Capacity, and Practices. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2013, 8, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, T.Y.; Freeland-Graves, J.H. Organizations of food redistribution and rescue. Public Health 2017, 152, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breetz, H.L.; Fisher-Vanden, K.; Jacobs, H.; Schary, C. Trust and Communication: Mechanisms for Increasing Farmers’ Participation in Water Quality Trading. Land Econ. 2005, 81, 170–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliore, G.; Caracciolo, F.; Lombardi, A.; Schifani, G.; Cembalo, L. Farmers’ Participation in Civic Agriculture: The Effect of Social Embeddedness. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2014, 36, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkmann, S. The interview. In Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 576–599. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, R.S. Learning From Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dedoose (version 8.3.10). SocioCultural Research Consultants; LLC: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: http://www.dedoose.com (accessed on 21 July 2020).

- Emerson, R.M.; Fretz, R.I.; Shaw, L.L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marshman, J.; Scott, S. Gleaning in the 21st Century: Urban food recovery and community food security in Ontario, Canada. Canadian Food Studies/La Revue canadienne des études sur l’alimentation 2019, 6, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetherill, M.S.; White, K.C.; Rivera, C.; Seligman, H.K. Challenges and opportunities to increasing fruit and vegetable distribution through the US charitable feeding network: Increasing food systems recovery of edible fresh produce to build healthy food access. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2019, 14, 593–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, E.; Jacxsens, L.; Goubert, H.; Uyttendaele, M. Ensuring food safety in food donations: Case study of the Belgian donation/acceptation chain. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Growers | 35 | 70.0% |

| Respondent role | ||

| Farmer/owner | 25 | 71.4% |

| Production manager | 7 | 20.0% |

| Sales | 3 | 8.6% |

| Crop | ||

| Leafy greens | 8 | 22.9% |

| Peaches | 11 | 31.4% |

| Tomatoes | 9 | 25.7% |

| Multiple crops | 7 | 20.0% |

| Farm acreage | ||

| 0–99 acres | 5 | 15.2% |

| 100–499 acres | 2 | 6.1% |

| 500–999 acres | 4 | 12.1% |

| 1000–4999 acres | 9 | 27.3% |

| 5000+ acres | 13 | 39.4% |

| Emergency food | 8 | 16.0% |

| Respondent role | ||

| Executive director | 2 | 25.0% |

| Food sourcing/procurement | 6 | 75.0% |

| Organization type | ||

| Food bank | 6 | 75.0% |

| Food kitchen | 1 | 12.5% |

| Hunger relief | 1 | 12.5% |

| Private businesses | 7 | 14.0% |

| Respondent role | ||

| CEO/Co-founder | 4 | 57.1% |

| Food sourcing/procurement | 2 | 28.6% |

| Sustainability manager | 1 | 14.3% |

| Organization type | ||

| Grocery delivery | 3 | 42.9% |

| Produce sales/distribution | 2 | 28.6% |

| Processing | 1 | 14.3% |

| Food service | 1 | 14.3% |

| Total | 50 | 100% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meagher, K.D.; Gillman, A.; Campbell, D.C.; Spang, E.S. Relational and Logistical Dimensions of Agricultural Food Recovery: Evidence from California Growers and Recovery Organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156161

Meagher KD, Gillman A, Campbell DC, Spang ES. Relational and Logistical Dimensions of Agricultural Food Recovery: Evidence from California Growers and Recovery Organizations. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156161

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeagher, Kelsey D., Anne Gillman, David C. Campbell, and Edward S. Spang. 2020. "Relational and Logistical Dimensions of Agricultural Food Recovery: Evidence from California Growers and Recovery Organizations" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156161

APA StyleMeagher, K. D., Gillman, A., Campbell, D. C., & Spang, E. S. (2020). Relational and Logistical Dimensions of Agricultural Food Recovery: Evidence from California Growers and Recovery Organizations. Sustainability, 12(15), 6161. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156161