A Study on the Sustainable Development of NPOs with Blockchain Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Existing Research

2.1. NPO’s Transparency and Governance Structure

2.2. Blockchain and Transparency/Governance

2.3. Blockchain Utilization for Building Sound Governance

3. Research Method

4. Case Study

4.1. BitGive

4.2. AidChain

4.3. Plans to Introduce Smart Contracts of UNICEF

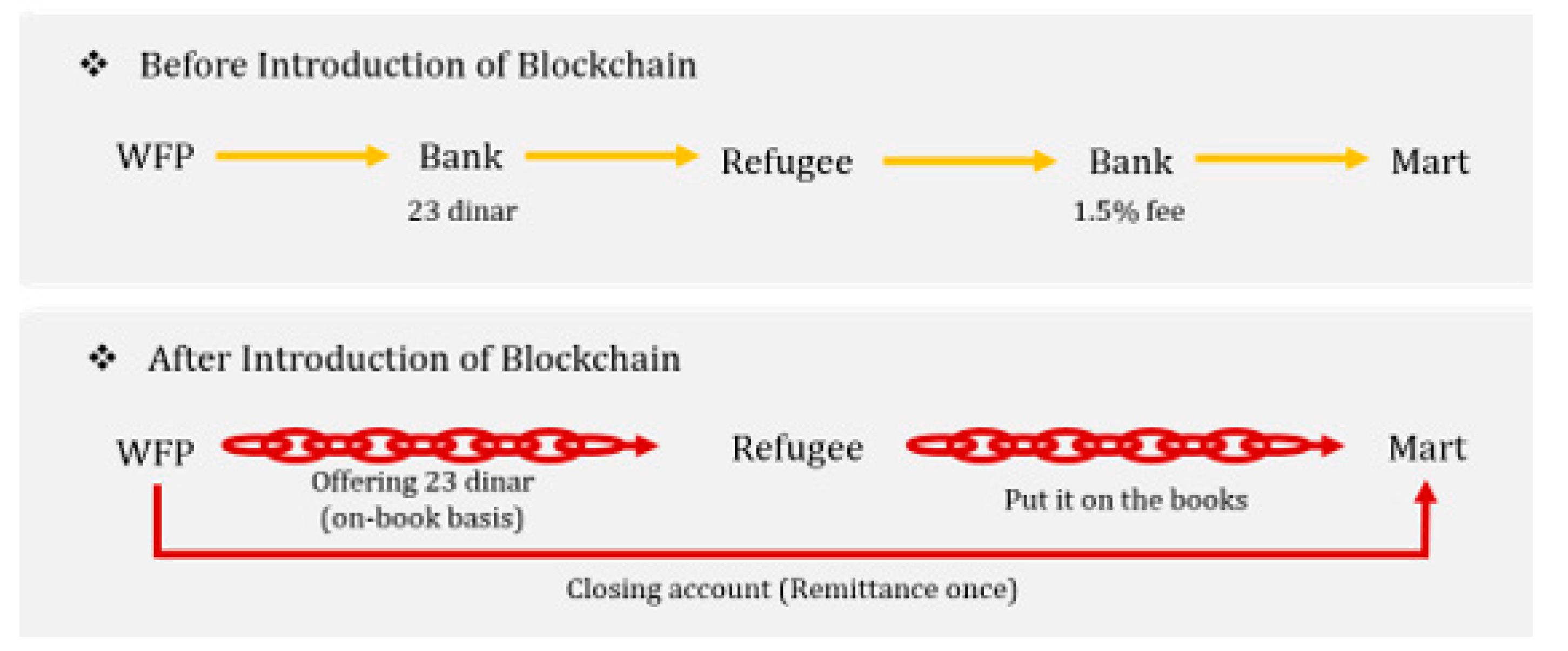

4.4. Building Blocks Project of the UN World Food Programme (WFP)

5. Discussion

5.1. Current Practice vs. Blockchain Applied Practice

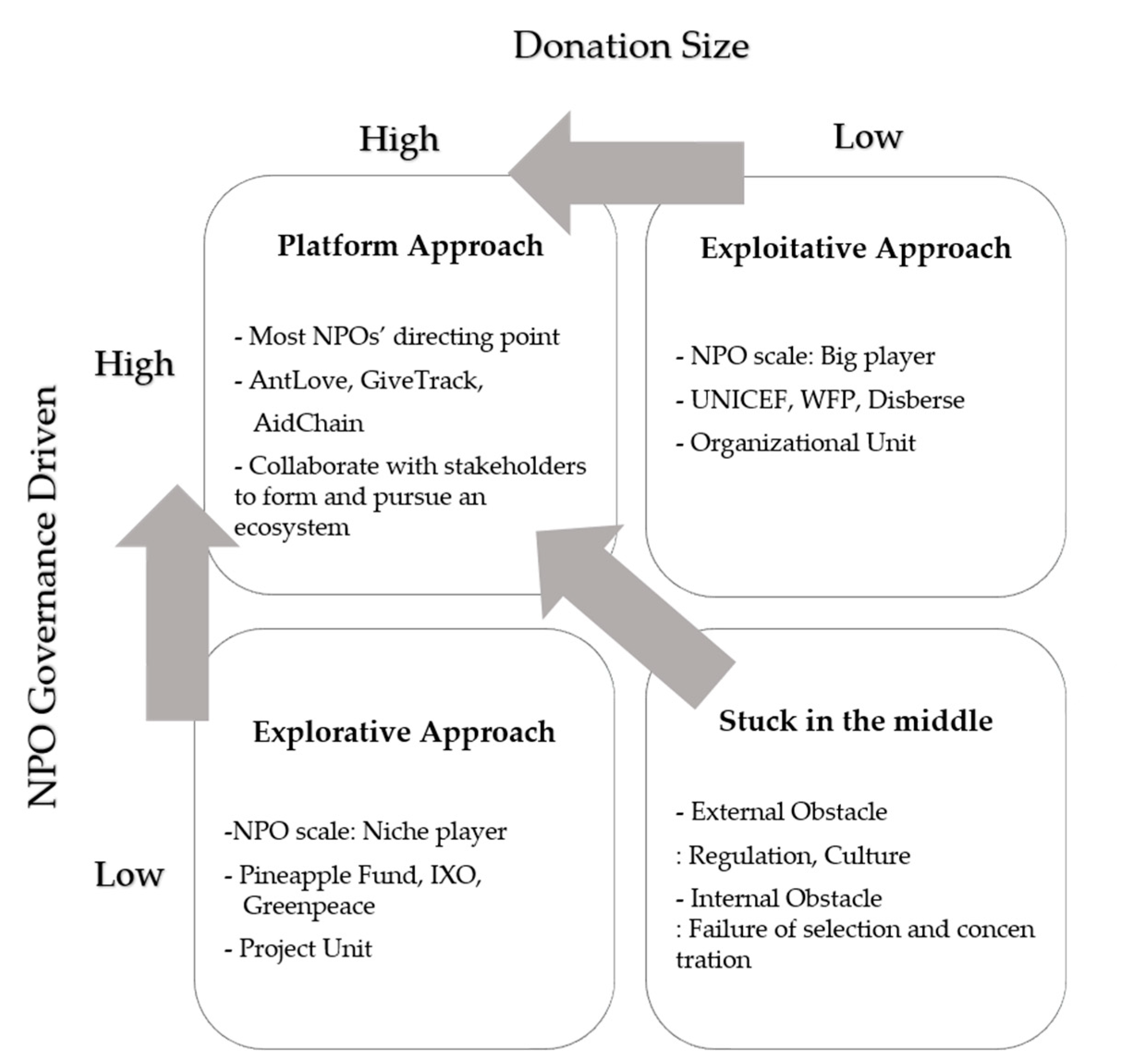

5.2. NPO’s Strategic Approach

5.2.1. Stuck in the Middle Stage

Low Contribution/Low Operational Efficiency

5.2.2. Exploitative Approach

Seeking Higher Operational Efficiency

5.2.3. Explorative Approach

Pursuit of Greater Contributions

5.2.4. Platform Approach

Expanding Donations and Seeking Operational Efficiency

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iwu, C.G.; Kapondoro, L.; Twum-Darko, M.; Tengeh, R. Determinants of sustainability and organisational effectiveness in non-profit organisations. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9560–9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyndman, N.; McDonnell, P. Governance and charities: An exploration of key themes and the development of a research agenda. Financ. Account. Manag. 2009, 25, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masruki, R.; Shafii, Z. The development of waqf accounting in enhancing accountability. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2013, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S. Opening up: Demystifying funder transparency. In GrantCraft: Practical Wisdom for Funders; The Foundation Center, European Foundation Centre: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: http://grantcraft.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/12/transparency.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2018).

- Yeo, A.C.; Chong, C.Y.; Carter, S. Governance practices and disclosure by not-for-profit organizations: Effect on the individual donating decision. In Empowering 21st Century Learners through Holistic and Enterprising Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 243–254. [Google Scholar]

- Atan, R.; Zainon, S.; Wah, Y.B. The extent of charitable organisations’ disclosures of information and its relationship with donations. Manag. Account. Rev. 2012, 11, 15–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, A.; Weisband, E. Global accountabilities. Camb. Camb. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A.; Gabaix, X. Executive compensation: A modern primer. J. Econ. Lit. 2016, 54, 1232–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, R. The role of NGO self-regulation in increasing stakeholder accountability; One World Trust: London, UK, 2005; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System 2008. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2019).

- Windley, P. How blockchain makes self-sovereign identities possible. Computerworld 2018. Available online: https://www.computerworld.com/article/3244128/how-blockchain-makes-self-sovereign-identities-possible.html (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Perlman, L. Distributed ledger technologies and financial inclusion. In International Telecommunications Union; 2017. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/focusgroups/dfs/Documents/201703/ITU_FGDFS_Report-on-DLT-and-Financial-Inclusion.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Nor, R.M.; Rahman, M.H.; Rahman, T.; Abdullah, A. Blockchain sadaqa mechanism for disaster aid crowd funding. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computing and Informatics: Embracing Eco-Friendly Computing, Kuala Lumpur; University Utara: Kedah, Malaysia, 2017; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.W.; Panayi, E. Understanding modern banking ledgers through blockchain technologies: Future of transaction processing and smart contracts on the internet of money. In Banking beyond Banks and Money; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 239–278. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, R. Blockchain and Financial Inclusion. Chamber of Digital Commerce and Georgetown University. 2017. Available online: https://digitalchamber.org/assets/blockchain-and-financial-inclusion.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Zambrano, R.; Seward, R.K.; Sayo, P. Unpacking the Disruptive Potential of Blockchain Technology for Human Development, International Development Research Centre: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. Available online: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/56662/IDL-56662.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Hsieh, D. IDHub Whitepaper v0. 5; 2018. Available online: www.idhub.network/IDHub_whitepaper_v0.5.0_en.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- Werbach, K. The Blockchain and the New Architecture of Trust; Mit Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Galen, D.; Brand, N.; Boucherle, L.; Davis, R.; do, N.; El-Baz, B.; Kimura, I.; Wharton, K.; Lee, J. Blockchain for social impact: Moving beyond the hype. Center for Social Innovation, RippleWorks. 2018. Available online: https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/sites/gsb/files/publication-pdf/study-blockchain-impact-moving-beyond-hype_0.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Yermack, D. Corporate governance and blockchains. Rev. Financ. 2017, 21, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, P. What if blockchain technology revolutionised voting. In Unpublished manuscript, European Parliament; 2016. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2016/581918/EPRS_ATA(2016)581918_EN.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Lee, J.; Seo, A.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, J. Blockchain-Based One-Off Address System to Guarantee Transparency and Privacy for a Sustainable Donation Environment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haahr, M. Hack the Future of Development Aid; Sustainia, 2017. Available online: https://um.dk/~/media/um/english-site/documents/danida/goals/techvelopment/hack%20the%20future%20december%202017v2.pdf?la=en (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Reiten, A.; D’Silva, A.; Chen, F.; Birkeland, K. MicroChain: Transparent Philanthropic Microlending; 2016. Available online: https://courses.csail.mit.edu/6.857/2016/files/16.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2018).

- Buterin, V. A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform. White Pap. 2014, 3.37. Available online: https://cryptorating.eu/whitepapers/Ethereum/Ethereum_white_paper.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2018).

- Jayasinghe, D.; Cobourne, S.; Markantonakis, K.; Akram, R.N.; Mayes, K. Philanthropy on the Blockchain. In Proceedings of the IFIP International Conference on Information Security Theory and Practice; Springer: New York, NY, USA; pp. 25–38.

- Poorterman, A. Start Network in new partnership with Disberse to test revolutionary technology. StartNetwork. com (July 11, 2017). Available online: https://startnetwork.org/news-and-blogs/blockchain-experiment-humanitarian-aid (accessed on 11 May 2018).

- Davies, R. Giving unchained: Philanthropy and the blockchain. 2015. Charities Aid Foundation. 2015. Available online: https://www.cafonline.org/docs/default-source/about-us-publications/givingunchained-philanthropy-and-the-blockchain.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Scott, B. How Can Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Technology Play a Role in Building Social and Solidarity Finance? United Nations Research Institute of Social Development: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.unrisd.org/brett-scott (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- Macheel, T. BitGive Becomes First IRS Tax Exempt Bitcoin Charity. Coindesk 2014. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/bitgive-becomes-first-irs-tax-exempt-bitcoin-charity (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Grad, J. How Blockchain Tech Can Help Solve Problems in Charity. In Finance Magnates; 2016; Volume 2018. Available online: https://www.financemagnates.com/cryptocurrency/bloggers/blockchain-tech-can-help-solve-problems-charity/ (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Pittman, A. The Evolution of Giving: Considerations for Regulation of Cryptocurrency Donation Deductions. Duke L. Tech. Rev. 2016, 14, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.; Lokam, S.; Jain, A.; Sivathanu, M.; Singanamalla, S. Vishrambh: Trusted philanthropy with end-to-end transparency. In HCI for Blockchain, Proceedings of the A CHI 2018 workshop on Studying, Critiquing, Designing and Envisioning Distributed Ledger Technologies, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–22 April 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gersick, C.J. Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 31, 9–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, A.M. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Validity and generalization in future case study evaluations. Evaluation 2013, 19, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnell, V.E. The uses of theory, concepts and comparison in historical sociology. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 1980, 22, 156–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragin, C.; Zaret, D. Theory and method in comparative research: Two strategies. Soc. Forces 1983, 61, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keirns, G. Alibaba Affiliate to Expand Blockchain Charity Project. Coindesk 2017. Available online: https://www.coindesk.com/alibaba-expand-blockchain-charity-project (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Kshetri, N. Will blockchain emerge as a tool to break the poverty chain in the Global South? Third World Q. 2017, 38, 1710–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.; Meyer, A.; Owens, J. Using blockchain for transparent beneficial ownership registers. Int’l Tax Rev. 2017, 28, 47. [Google Scholar]

- BitGive Foundation. Available online: https://www.bitgivefoundation.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Saleh, H.; Avdoshin, S.; Dzhonov, A. Platform for Tracking Donations of Charitable Foundations Based on Blockchain Technology. In Proceedings of the 2019 Actual Problems of Systems and Software Engineering (APSSE), Moscow, Russia, 12–14 November 2019; pp. 182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, R.N.; Mayes, K. Philanthropy on the Blockchain. In Proceedings of the Information Security Theory and Practice: 11th IFIP WG 11.2 International Conference, WISTP 2017, Heraklion, Greece, 28–29 September 2017; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- AIDCHAIN. Available online: https://www.aidchain.co/ (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Mohsin, M.I.A.; Muneeza, A. Integrating waqf crowdfunding into the blockchain. In Fintech in Islamic Finance: Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, K. Blockchain for Development–Hope or Hype? In Institute of Development Studies; 2017. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/12945/RRB17.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- Pineapple Fund. Available online: https://pineapplefund.org/ (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Fabian, C. Un-chained: Experiments and Learnings in Crypto at UNICEF. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2018, 12, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodgson, M.; Gann, D. Controversies and Future Challenges. In Philanthropy, Innovation and Entrepreneurship; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Craighill, C. Greenpeace Now Accepting Bitcoin Donations. Available online: https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/greenpeace-now-accepting-bitcoin-donations/ (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Richards, M. Disruptive Innovations: Blockchain and Spinoffs’. In Advances in the Technology of Managing People: Contemporary Issues in Business (The Changing Context of Managing People); Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Howson, P. Building trust and equity in marine conservation and fisheries supply chain management with blockchain. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IXO Foundation. Available online: http://ixo.foundation/ (accessed on 9 October 2019).

- Zhang, X.; Aranguiz, M.; Xu, D.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X. Utilizing blockchain for better enforcement of green finance law and regulations. In Transforming Climate Finance and Green Investment with Blockchains; Academic Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 2018; pp. 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Unicef Office of Innovation. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innovation/blockchain (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Lubin, J.; Anderson, M.; Thomason, B. Blockchain for Global Development. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2018, 12, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouda, Q. UNICEF Ventures: Exploring Smart Contracts. UNICEF Innovation: 2017. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innovation/blockchain/ventures-exploring-smart-ethereum-contracts (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Association, G. Blockchain for Development: Emerging Opportunities for Mobile, Identity and Aid. 2017. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Blockchain-for-Development.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Disberse. Available online: Disberse.com (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Rugeviciute, A.; Mehrpouya, A. Blockchain, a panacea for development accountability? A study of the barriers and enablers for Blockchain’s adoption by development aid organizations. Front. Blockchain 2019, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsberg, B. Blockchain technology and the governance of foreign aid. J. Inst. Econ. 2019, 15, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Food Programme. Building Blocks. Available online: https://innovation.wfp.org/project/building-blocks (accessed on 2 August 2019).

- Zambrano, R.; Young, A.; Velhurst, S. Connecting Refugees to Aid through Blockchain Enabled Id Management: World Food Programme’s Building Blocks; GovLab October, 2018. Available online: https://blockchan.ge/blockchange-resource-provision.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2019).

- Bajpai, P. How Blockchain Can Help Humanitarian Causes. Nasdaq: 2017. Available online: http://www.nasdaq.com/article/how-blockchain-can-help-humanitarian-causes-cm879186 (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Cohen, H. Building Blocks: The Future of Cash Disbursements at the World Food Programme @ TechNovation; United Nations OICT, 2017. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/c/UnitedNationsOICT/channels (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Blockchain Could Transform Identification and Aid Processes for Refugees. International Development Forum: 2018. Available online: http://www.aidforum.org/Topics/disaster-relief/blockchain-could-transform-identification-processes-for-refugees (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Juskalian, R. Inside the Jordan Refugee Camp That Runs on Blockchain; MIT Technology Review: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kenna, S. How Blockchain Technology Is Helping Syrian Refugees. Huffington Post 05 Nov 2017, 2017. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com.au/2017/11/05/how-blockchain-technology-is-helping-syrian-refugees_a_23267543/ (accessed on 11 August 2019).

- Blockchain against Hunger: Harnessing Technology In Support Of Syrian Refugees. WFP Innovaton: 2017. Available online: http://innovation.wfp.org/blog/blockchain-against-hunger-harnessing-technology-support-syrian-refugees (accessed on 2 August 2019).

- Kshetri, N. Can Blockchain Technology Help Poor People around the World?; The Conversation, 2017. Available online: https://theconversation.com/can-blockchain-technology-help-poor-people-around-the-world-76059 (accessed on 10 May 2018).

- Hsu, C.-S.; Tu, S.-F.; Huang, Z.-J. Design of an E-Voucher System for Supporting Social Welfare Using Blockchain Technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NGO Reference Model. Available online: https://www.ngoreferencemodel.org/ (accessed on 12 July 2020).

| Goal | Method | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Increase donation | Development of a donation platform | Share real-time data on donations and their use, thereby increasing transparency and ease of use. |

| Adoption of cryptocurrency | Convenience, anonymity, and low fees for transfers and donations. | |

| Expansion of social contribution | Add value to NPOs using blockchains (transforming intangible value, such as volunteer work, into tangible value, and operating annuity for self-help of donor recipients). | |

| Utilization in business operation | Operational efficiency, transparency | Real-time information sharing using distributed ledgers for fund movement, operation, and business management. Smart contracts are automatically executed when conditions are met to prevent intervention and manipulation by brokers. |

| Economic efficiency of operation | Decrease financial commission, labor costs, and time spent by not using existing financial networks. |

| Classification | Case Name | Characteristics | Progress and Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Donation platform development | Alibaba | Alipay app allows donors to check where NPOs need support in real time and make donations. All processes are logged and shared through a blockchain. | Launched the system in 2016 and applied blockchain technology in 2017 to Ant Love. More than 400 million Alipay users can access charity platform. |

| (Ant Love) [40,41,42] | |||

| Donation platform development/donation through cryptocurrency | BitGive (GiveTrack) [26,43,44,45] | Allows one to choose from a list of villages on the platform that one would like to help by sending bitcoin to bitcoin addresses owned by GiveTrack. Real-time visibility into project status. | Considered the first system of donating money through Cryptocurrency in the US. |

| Donation platform development/donation through cryptocurrency | AidChain [46,47,48] | A donation platform based on the Ethereum blockchain that enables charities, donors, and recipients to track the process of donation and the use of donations through the Transparency Engine application. | Developing a payment portal, AidPay, that can transform cryptocurrency into its own donor coin, AidCoin. |

| Donation through cryptocurrency | Pineapple fund [49,50,51] | All participants, as well as the founder of the fund, can donate through cryptocurrency to ensure individual anonymity. | Donated US$55 million worth of Bitcoin to 60 charities. Ended 11 May 2018. |

| Donation through cryptocurrency | Greenpeace [52,53,54] | Partnering with the Bitcoin payment company Bitpay to receive Bitcoin donations and 100% of donations without fees. | Greenpeace operates on private donations for non-profit purposes, rather than accepting donations from businesses or the government. Collects steady bitcoin donations in a transparent manner. |

| Compensation and donation for social contribution activities | IXO Foundation [55,56] | Tokenized the social impact of philanthropy—once confirmed, tokens are given, which can be used for future donations. | Records children’s participation in education in South Africa and issues a token. In addition, the platform is used for various philanthropic activities in developing countries. |

| Classification | Case Name | Characteristics | Progress and Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased operational transparency/convenience | United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) smart contract [50,57,58,59] | Using smart contracts, deals are programmed to be executed automatically when conditions are met. Transactions through blockchain provide transparency. | Investment, technology development to implement smart contracts through UNICEF Ventures. Transparency is greatly enhanced by all information, activities, and the disclosure of transactions. |

| Increased operational transparency/convenience/reduced operating costs | Disberse [60,61,62,63] | A fund management platform using a blockchain, which drives efficient and transparent flow and delivery aid. Each stakeholder can track funds from donors to beneficiaries. | Reduces the commission of contributions remitted for education projects in Swaziland by 2.5%. Support three students for an annual tuition with the saved fee. |

| Reduced operating costs | United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] | Utilizes Ethereum blockchain technology for refugee aid. Significantly reduces financial fees, labor costs, and time spent. | In May 2017, it delivered food e-coupons worth US$1.4 million to about 10,000 Syrian refugees in Jordan. E-coupon transactions were recorded in the blockchain. |

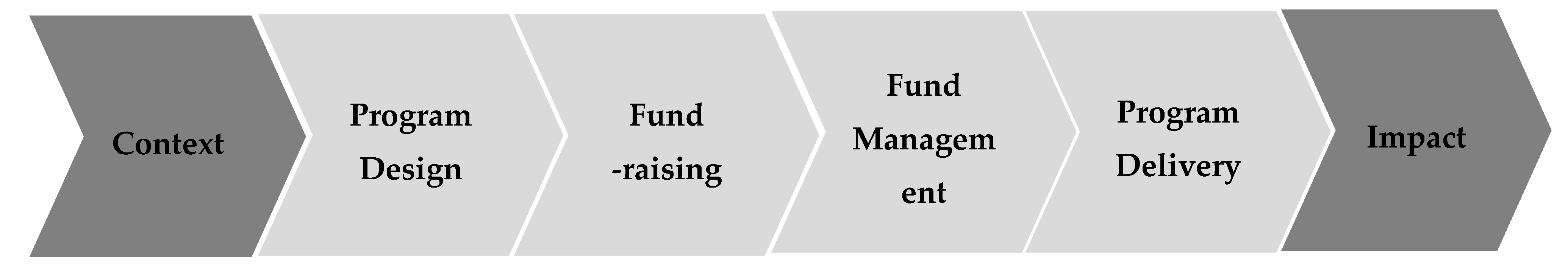

| Category | Program Design | Fundraising | Fund Management | Program Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major Activities | -Develop implementation plan. -Capacity assessment. | -Fundraising activity. -Donor-led program design. | -Understand donor and funding requirement. -Donor reporting. | -Logistics -Provide information and communicate with stakeholders. |

| Current Practice | -Relying on local human resources. -Process design is different depending on beneficiaries’ regional conditions. -Plan to track program implementation and manage related data. | -Approach local direct donation program or corporate donation. -Increase interest with advertisement or promotion. | -Manually monitor and gather partial information from each step. -Quarterly or annually prepare report and deliver information via email, mail or homepage posting. | -In case of global project, implementation is done by local team via many intermediaries. -Gather data spreading out the whole process. -Report quarterly or annually with limited data. |

| Limitation | -Manual design process. -Program design limitation in the poor infrastructure region. -Limitation or delay in tracking program performance. | -Inconvenience of donors due to limited donation method. -Incentive of donation is only goodwill. -Increase promotion cost. | -Manual management of restricted or unrestricted funds of the program causing delay in monitoring. -Delayed reporting with limited information. | -Operational limitation with high cost due to financial intermediaries. -Manual collection of partial data incurring high cost and low efficiency.-Delayed reporting with limited information. |

| Applying Blockchain | -Less manual with smart contract. -Reduces the process with intermediaries. -Real-time reporting process. | -Increases convenience through crypto token helps expand donor groups. -Increases interest by incentivizing the usage of token. -Tracks project status from donation to receiving of benefits. | -Tracks and monitors donations and the utilization of funds on a real-time basis. -Automatic fund management through smart contract. -Real-time information sharing with stakeholders. | -Build up digitalized blockchain infrastructure for fund and data management. -Collection of dispersed data. -Real-time information sharing with stakeholders. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shin, E.-J.; Kang, H.-G.; Bae, K. A Study on the Sustainable Development of NPOs with Blockchain Technology. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156158

Shin E-J, Kang H-G, Bae K. A Study on the Sustainable Development of NPOs with Blockchain Technology. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156158

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Eun-Jung, Hyoung-Goo Kang, and Kyounghun Bae. 2020. "A Study on the Sustainable Development of NPOs with Blockchain Technology" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156158

APA StyleShin, E.-J., Kang, H.-G., & Bae, K. (2020). A Study on the Sustainable Development of NPOs with Blockchain Technology. Sustainability, 12(15), 6158. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156158