Abstract

Food waste (FW) has been linked with nutrient intake, menu performance, food acceptability, costs and environmental impacts. This study aims to evaluate the FW in the wards of a Portuguese public hospital. The evaluation of the FW of lunch meals was performed during 21 days, to all new hospitalized patients (n = 105) admitted in four hospital wards (Medicine (Med), Paediatrics (Ped), Oncology (Onc) and Orthopaedics (Ort)). For each patient, the type of diet and FW were evaluated during the length of hospital stay (covering 321 meals). The FW of the dish was calculated by the physical method by weighing and the soup by the method of visual estimation, evaluating before and after distribution. The patients have a mean 3.1 ± 2.2 day length of hospital stay. In relation to the FW of the dish per ward, that in the Ped ward it was 72.6%, Med 47.5%, Onc 46.9% and Ort 58.4% (ρ = 0.027). The FW for Ped soup was 67.1%, Med 30.9%, Onc 29.4% and Ort 35.2% (ρ = 0.018). The FW values are high, especially in the paediatric ward. The institutions are unaware of the FW produced and given the magnitude of the problem it is necessary to implement effective measures.

1. Introduction

The hospital’s food service is a fundamental issue in patient care, being crucial in their recovery [1]. From the food preparation to the distribution, the hospital’s food service must always provide safe food and within the defined standards about nutritional quality and adequacy, palatability and temperature [2]. Therefore, meals served during the length of hospital stay are an extremely important condition for hospital treatment and for patient recovery [3,4]. The provision of adequate diets to the patient should be the responsibility of the food and nutrition service of each hospital, and the hospital diet must guarantee the adequate supply of nutrients to the hospitalized patient, allowing it to preserve and/or recover its nutritional status through its co-therapeutic role in chronic and acute diseases [5].

Food waste (FW) has become an object of discussion of the hospital food service [6,7,8], since it is seen as the cause of many negative effects, including health, economic, social and environmental issues [9].

According to Williams and Walton [10], FW is two to three times greater in hospitals than in other areas of food services. This study suggested some factors with impact on FW, such as the clinical condition of the patients, the number of portions and the available alternatives, the ward, the difficulty in accessing food, the type of menus, the meal production system and the quality of the food.

In Italy, one study estimated that about 41.6% of food served to patients admitted to three hospitals was wasted [11]. The preventive measures suggested to hospitals to combat FW were to establish an individualized meal food service, to simplify and flexibilize the meal production process based on specific nutritional needs, preferences and choices of the patient and to improve the food service based on consumer satisfaction surveys.

In 2015, one characterization of FW (food served, but not consumed) in an intensive care hospital in Portugal was performed and was estimated that on average, each patient wasted around 35% of food per day (with an associated cost of € 3.9 and an emission cost of 1.8 kg of CO2 (equivalent)). All these tons of food (around 8.7 thousand tons per year across the country) turned into waste are equivalent to economic losses and environmental impacts. Most hospital institutions are unaware of how much FW they generate, and the associated costs [12].

Simzari et al. [13] studied the relationship between hospital malnutrition and FW and concluded that hospital malnutrition is highly prevalent simultaneously with a high rate of FW and nutritional risk, suggesting that high wastage rates were associated with inadequate energy and protein intakes, which may help to explain patient weight loss during a hospital stay.

It has been noted that an increased number of patients admitted to hospitals are malnourished, and that this clinical situation can be worsened if remained untreated during the hospital stay, which can result in increased morbidity, prolonged hospital stay, and poor survival [13,14,15].

The prescription of diets adapted to the nutritional needs of patients, with adequate food and consistency, and pleasant to the taste, is a strategy to combat malnutrition in the hospital [16]. Indeed, hospital meals with a good quality and well adapted to nutritional support is a complementary part of the therapeutic aid in a hospital. This includes the planning of menus and the improving of the presentation of meals as strategies for a better acceptance of diets by patients, as well as a consequent reduction in food waste (FW) [17].

To that end, the aim of our study was to estimate and evaluate the FW generated by patients from four wards during the length of hospital stay in a Portuguese public hospital from the north of the country.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Meals Production

The present study was carried out in a Portuguese public hospital, from the north of the country, where over 21 days the FW of meals served at lunch was evaluated for all new patients admitted in the paediatric, medicine, oncology and orthopaedic wards. We analysed 105 hospitalized patients, covering a total of 321 meals. Meals were produced according to the cook-chill system and served hot.

The type of diet consumed was also evaluated: standard paediatric, standard adult, light, soft texture and cream texture.

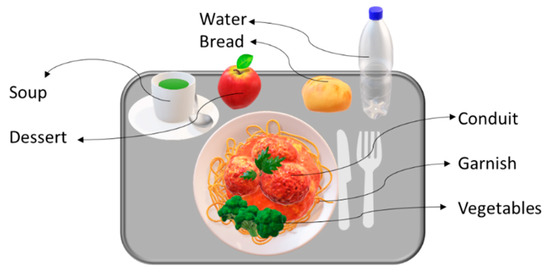

Patients admitted to the hospital received a lunch meal consisting of the following items: soup, dish, bread, dessert and water, in which the dish consists of the three components: conduit, garnish and vegetables [18] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Constitution of the lunch meal and components of the dish item.

The components present in a meal dish provide different sources of nutrients; that is, the conduit is the main source of protein (meat, fish and eggs group and/or legume group, when applicable), the garnish is the main source of supply of carbohydrates (group of cereals and derivatives, tubers and/or group of legumes, when applicable), and finally vegetables are the main source of dietary fibre and micronutrients (group of vegetables) [18].

Some meals under study are compound meals, that is, the three components (conduit, garnish and vegetables) are mixed together on the plate (for example: meat lasagne, duck rice, Portuguese bean stew). We counted 112 compound meals for adult patients and 11 compound meals for paediatric patients (from 321 meals).

The diets are distinguishable by the type of confection and composition, according to the hospital diet manual [19]:

- (a)

- the standard paediatric diet, consisting of a complete and balanced diet for children of paediatric age, in which lunch consists of a diet of soft consistency;

- (b)

- the standard adult diet, which is a complete and balanced diet designed according to the principles of healthy eating and applies to patients who do not need specific dietary changes;

- (c)

- the light diet, which is a therapeutic diet with fat restriction, applicable to adults whose clinical diagnosis requires facilitated digestion;

- (d)

- the soft texture diet, which is a therapeutic diet with a modified texture, based on easily chewable foods, intended for patients with chewing problems without the need of creamy foods;

- (e)

- the creamy texture diet, consisting of a modified texture therapeutic diet, based on homogeneous cream consistency foods, intended for patients with severe chewing and/or swallowing problems or risk of aspiration pneumonia, due to dysphagia for liquids or heterogeneous food.

In our study, was evaluated the FW of hospitalized patients who consumed the above-mentioned diets. All patients with parenteral nutrition, tube feeding and liquid diets and supplements were excluded from the evaluation of this study.

2.2. Food Waste

The FW of the dish was calculated by the physical method of weighing the meal plate carrying out the assessment before and after the distribution of the trays, following the procedures of the European Commission Standard methodology approved in 2019 [20]. For the soup, the visual estimation method was used, using a percentage scale after the distribution of the trays. FW was assessed on every working day.

The weight of the food was measured in grams by a portable high precision electronic kitchen scale (Jata 722P, Portugal) with a capacity of 5 kg and precision of 0.1 g. Measurements were taken in two stages each day, that is, the amount of food served and the amount of food scraps in order to obtain FW, using the following formula:

FW (%) = Food Scraps/Food Served ∗ 100

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The analyses were carried out using the statistical software IBM SPSS STATISTICS Version 20. The statistical analysis involved measures of descriptive statistics (absolute and relative frequencies, means and respective standard deviations).

To compare means of two independent samples, non-parametric tests were used, that is, the Mann-Whitney test and the Kruskcal-Wallis test. The degree of association between variables was calculated using Spearman’s correlation coefficient (ρ). The null hypothesis was rejected when the critical significance level was less than 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

The present study included 105 patients, 15 from paediatric wards (mean age 7; 60% male), 23 from medicine (average age 75; 57% male), 27 from oncology (mean age 67; 63% male) and 40 from orthopaedics (mean age 70; 45% male) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants.

The average number of days of hospitalization per adult participant was 3 days and 1 day in children of paediatric age, having analysed 321 meals over that period (20 standard paediatric, 150 standard adult, 64 light, 50 soft texture and 36 cream texture).

3.2. Assessment of Food Waste

During the evaluation period, patients were served 112.72 kg of food at the lunch meal (in 321 meals). On average the FW of the dish was 56.4%. The hospital serves an average of 350 meals daily, so our study allowed us to estimate that 75.58 kg of the food served at lunch in this public hospital was wasted per day.

The average percentage of FW during lunch on the plate and in the soup for adults (n = 90) was 52.2 ± 27.6% and 32.4 ± 9.2%, respectively. It was also found that, in adults, the plate waste was positively associated with the soup waste (ρ = 0.242, p = 0.022). In the case of children patients (n = 15), FW was 72.6 ± 41.5% in the dish and 67.1 ± 41.8% in the soup.

The Table 2, shows the FW of the dish per ward. It can be noted that FW in paediatric ward was 72.6%, in medicine 47.5%, oncology 46.9% and orthopaedics 58.4% (ρ = 0.027), and a higher FW was observed in the dish made for female users (61.4% vs. 49.8%; ρ = 0.043). Regarding soup, the FW in the paediatric ward was 67.1%, medicine 30.9%, oncology 29.4% and orthopaedic 35.2% (ρ = 0.018).

Table 2.

Food waste (FW) by hospital ward, type of diet and patient gender.

There was no correlation between the type of diet and the FW of the dish (ρ = 0.107; ρ = 0.275) and of the soup (ρ = 0.190; ρ = 0.053). However, the FW was significantly higher for the standard paediatric diet, both in the dish (72.6%) and in the soup (67.1%), and lower in the light diet (39.8% in the dish and 14.9% in the soup). The higher percentage of FW in the main dish in the adults’ wards was observed for the soft texture diet (65.1%) (Table 2).

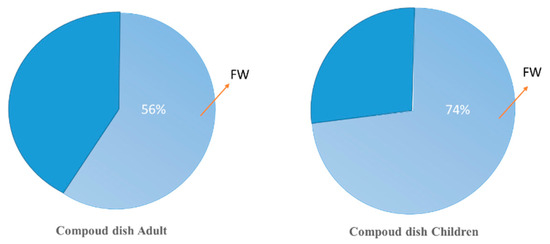

With regard to the components that make up the lunch meal dish, regarding the compound meals (n = 123), in adult and paediatric patients, a FW of 55.8% and 74.2%, respectively, was detected (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Food waste from compound meals.

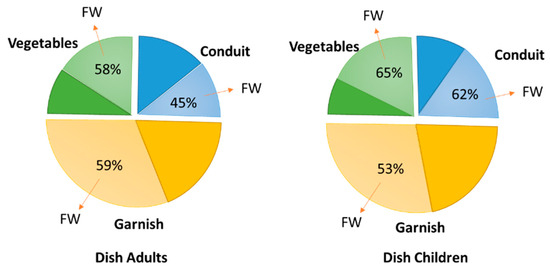

With regard to the meals with separated components (n = 198), it was found that both components had high and close values of FW; in adult patients, the garnish had the highest value of FW, around 58.6%, followed by vegetables with a relatively close value of 57.6% and finally the least wasted component, the conduit, with 45.2%. For patients of paediatric age, the most wasted component was vegetables with 65.4% of waste, and the least wasted was the garnish with 53.3% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Food waste (%) of each component of the dish.

It should be noted that out of the 90 adult patients in study, 8 patients wasted the entire meal dish, while 5 patients wasted all the soup, 13 patients all the garnish, 8 patients all the conduit and 10 patients left all the vegetables on the plate (FW = 100%).

Analysing the data on the assessment of FW over the days of hospitalization, it appears that the percentage of FW throughout this study always showed high values and fluctuations, emphasizing that the highest percentage of FW was observed on the day of hospital admission, which may be due to the patient’s clinical condition leading to hospitalization. In our study, the FW tends to decrease over the days of hospitalization (ρ = −0.215, p = 0.042).

4. Discussion

One of the concerns in managing a food service should be FW, as it is considered a quality parameter [21,22,23]. This issue is extremely important as it has a great impact on all hospitals and its solution requires a holistic approach.

The FW of the main dish in adults of our study (FW = 52.2%) was very similar to the FW found by Dias-Ferreira et al. (2015) [12] in another Portuguese hospital (FW was 52%). However, the FW that was found in our study in relation to soup was higher (FW = 32.4% vs. 12%).

If the values used by Dias-Ferreira et al. [12] to estimate the economic and environmental impact of the FW were used the present study, the FW would have had an impact of € 0.88 per patient and 0.41 kg of CO2. Although these results have great limitations, they allow us to have an idea of the magnitude of its impacts, even more when it is estimated that FW is greater in hospitals than in other food services [10].

Other previous studies have evaluated FW in catering units at hospital environment. Botelho et al. [24], using the weighing method, obtained values of 30.3% for the main dish and 12.6% for the FW soup. Mouta [25] obtained an average value of 31.2% in the lunch meal, and the component of the most wasted meal was soup, contrarily to the results observed in our study. In both cases, there was a value lower than the value obtained in the present study. These differences can be explained by several factors that affect FW such as the wards analysed, the meal production systems, the menus, the seasonality, the managements of food service and the methodology of FW analysis.

In the study of Dias-Ferreira et al. [12] some analogies were found with our study, when assessing the comparison of FW, including differences between the wards, with some generating more waste than others. In fact, our study also showed differences of waste generated by wards as paediatrics had a very high value compared to other wards. In one study from Brazil, it was found that the amount of hospital FW varied between 36% and 61% from the total waste per patient per day, dependent on the ward. The wards that generated more FW obtained values in the order of 1.55 kg of total waste, from which 0.95 kg was FW [26]. Compared to the wards evaluated in our study, the above-mentioned study had higher FW for all wards, presenting a range of FW between 46.7% and 72.6% for the dish and 29.4% and 67.1% for the soup.

It should be noted that in the hospital of this study the paediatric diet have a weekly repeated menu in order to be more appealing to children, but given the high percentage of FW, new approaches could be explored. Our results of FW in paediatric wards were much higher than the results found by Silva et al. [27] in paediatric wards in another public Portuguese hospital, which had a sample of 22 children, and estimated a FW of 40% of the three main meals.

The high percentage of FW found in the main dish of the soft diet can be explained by the fact that patients are more debilitated and many of them need help to feed themselves, so this individualized approach requires more human and economic resources. Mouta [25] also mentions that the soft diet was the one that had the highest percentage of FW and that the patients who needed help in taking meals and did not have their normal appetite were those who wasted more.

We also found that the FW produced by female patients was higher. These results were in line with the results that were obtained by Schiavone et al., 2019 [11], who reported that women wasted more food than men during hospitalization (59.1% vs. 38.2%). The study of FW according to gender was considered important because the requirements for certain nutrients differ for men and women, so some authors consider that this analysis should be realized [28].

According to the components of the dish, we found that for adults the garnish is the most wasted and that for children it is the vegetables. In the study of Schiavone et al. [11], the most wasted component was the vegetables (55.0%) and the least wasted was the garnish (38.5%). While in paediatric patients in other study [27], the most wasted component was vegetables almost entirely (90.7%) and the most consumed was the conduit (78.5%). These values are extremely high, as it is known that the intake of fruits and vegetables in school-aged children is below that recommended by the WHO (≥400 g) [29], so the adoption of strategies like offering selective menus can be used to reduce vegetables waste at paediatric ages [30].

Meal production system can also have impact on FW. One previous study estimated the differences between the plate regeneration system and the bulk regeneration system, and verified that in the plate system FW was relatively higher (65%) than the bulk system (17%). In our study, the meal production system was plate regeneration and it can be concluded that the FW detected was lower than that quantified in the previous study [31], however was higher than another study with hospital cook-freeze production system [32].

Simzari et al. [13] found that the high percentage of hospital FW is strongly interconnected with hospital malnutrition, determining that during the hospital stay weight reduction occurred in 53.3% of individuals. It is well understand since hospital meals are carefully planned so that the patients obtain all their nutritional needs from the food served, so when food is wasted it means that patients are not getting enough energy and nutrients [31].

The prevalence of malnutrition in the Portuguese internal medicine ward population was estimated by a cross-sectional multicentre study in 24 Portuguese Hospitals in 2017, and it was estimated that 56% of the patients had suspected/moderate malnutrition and 17% were severely malnourished [33]. According to Marinho et al. [34] the prevalence of hospital malnutrition is high in wards such as internal medicine, surgery, neurology, oncology and gastroenterology, among others, having a high impact on society and in the economy, estimating its direct and indirect impact at European level by around 170 billion euros.

Our study has as strengths the fact that it uses a direct methodology to estimate FW, giving great accuracy to the results, and is one of the few studies about FW on Portuguese hospitals. However, it also has some limitations, such as the fact that it does not assess the reasons patients decided to leave food on the plate, does not evaluate FW of bread and dessert and does not assess FW in other Portuguese hospitals to compare results including different meal production systems. These limitations represent important points for future research.

5. Conclusions

The data obtained in this study draws attention once again to the fact that FW is a problem that needs to be urgently debated in order to apply preventive measures as a rule to proceed with its reduction, as it causes damage at the social, economic and environmental levels. This subject needs more attention by researchers, especially at a clinical level.

The percentage of FW detected in this hospital in the north of Portugal was high, about 56.4% on the plate and 37.3% in the soup, with significant differences between wards and gender of patients. The development of effective measures to monitor and control FW were imperative and the knowledge of FW characterization can bring important clues to the design of intervention strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and C.G.; methodology, A.G., C.S. and C.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G. and C.G; writing—review and editing, C.S. and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The CECAV is supported by FCT/UIDB/CVT/00772/2020. The CIAFEL is supported by FCT/UIDB/00617/2020. The CITAB is supported by FCT/UIDB/04033/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jonkers, C.F.; Prins, F.; Van Kempen, A.; Tepaske, R.; Sauerwein, H.P. Towards implementation of optimum nutrition and better clinical nutrition support. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 20, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.M.; Bristow, A. Managing Nutrition in Hospital: A Recipe for Quality; Nuffield Trust: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Greathouse, K.R.; Gregoire, M.B. Variables related to selection of conventional, cook-chill, and cook-freeze systems. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1988, 88, 476–478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hickson, M.; Fearnley, L.; Thomas, J.; Evans, S. Does a new steam meal catering system meet patient requirements in hospital? J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 20, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, J.P.; Keller, H.; Teterina, A.; Jeejeebhoy, K.N.; Laporte, M.; Duerksen, D.R.; Gramlich, L.; Payette, H.; Bernier, P.; Davidson, B.; et al. Factors associated with nutritional decline in hospitalised medical and surgical patients admitted for 7 d or more: A prospective cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 1612–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almdal, T.; Viggers, L.; Beck, A.M.; Jensen, K. Food production and wastage in relation to nutritional intake in a general district hospital--wastage is not reduced by training the staff. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 22, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, A.D.; Beigg, C.L.; Macdonald, I.A.; Allison, S.P. High food wastage and low nutritional intakes in hospital patients. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 19, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.S.; Nash, A.H. The nutritional implications of food wastage in hospital food service management. Nutr. Food Sci. 1999, 99, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherhaufer, S.; Moates, G.; Hartikainen, H.; Waldron, K.; Obersteiner, G. Environmental impacts of food waste in Europe. Waste Manag. 2018, 77, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.; Walton, K. Plate waste in hospitals and strategies for change. Eur. e-J. Clin. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 6, e235–e241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, S.; Pelullo, C.P.; Attena, F. Patient Evaluation of Food Waste in Three Hospitals in Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Ferreira, C.; Santos, T.; Oliveira, V. Hospital food waste and environmental and economic indicators —A Portuguese case study. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simzari, K.; Vahabzadeh, D.; Nouri Saeidlou, S.; Khoshbin, S.; Bektas, Y. Food intake, plate waste and its association with malnutrition in hospitalized patients. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marinho, R.; Pessoa, A.; Lopes, M.; Rosinhas, J.; Pinho, J.; Silveira, J.; Amado, A.; Silva, S.; Oliveira, B.; Marinho, A.; et al. High prevalence of malnutrition in Internal Medicine wards—A multicentre ANUMEDI study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 76, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidelix, M.S.P.; de França Santana, A.F.; Gomes, J.R. Prevalência de desnutrição hospitalar em idosos. Rev. Assoc. Bras. Nutr. 2013, 5, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Diário da República, Order No. 5479/2017 of the Assistant Secretary of State and Health. Available online: https://dre.pt/application/conteudo/107550454 (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Antunes, M.T.; Dal Bosco, S.M. Gestão em Unidades de Alimentação e Nutrição da Teoria à Prática; Editora Appris: Curitiba, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.; Ávila, H.; Oliveira, B.; Franchini, B. Capitações de Géneros Alimentícios Para Refeições em Meio Escolar: Fundamentos, Consensos e Reflexões; Associação Portuguesa de Nutrição: Porto, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, A.; Pedrosa, C.; Ferro, G.; Real, H.; Fonseca, I.; Alves, P.; Lourenço, S.; Brandão, S.; Themudo, T. Linhas Orientadoras Para a Construção de um Manual de Dietas; Associação Portuguesa de Nutrição: Porto, Portugal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission; Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety. Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019 supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards a common methodology and minimum quality requirements for the uniform measurement of levels of food waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L248, 77–85, IMMC: C(2019)3211/1017440. [Google Scholar]

- Bradacz, D.-C. Modelo de Gestão da Qualidade Para o Controle de Despedício de Alimentos em Unidades de Alimentação e Nutrição; Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Abreu, E.S.; Spinelli, M.G.N.; de Souza Pinto, A.M. Gestão de unidades de alimentação e nutrição: Um modo de fazer; Editora Metha: São Paulo, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nonino-Borges, C.B.; Rabito, E.I.; Silva, K.D.; Ferraz, C.A.; Chiarello, P.G.; Santos, J.S.; Marchini, J.S. Desperdício de alimentos intra-hospitalar. Rev. Nutr. 2006, 19, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botelho, G.; Alegre, M.; Campos, M.J.; Rocha, A. Caracterização do desperdício alimentar numa unidade de alimentação coletiva em ambiente hospitalar. Aliment. Hum. 2014, 20, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mouta, A.C.M. Avaliação do desperdício alimentar de um serviço de alimentação e seus determinantes numa unidade hospitalar. Master’s Thesis, Portuguese Catholic University, School of Biotechnology, Porto, Portugal, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mattoso, V.D.; Schalch, V. Hospital waste management in Brazil: A case study. Waste Manag. Res. 2001, 19, 567–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asseiceira, I.; Mexia, S.; Patrício, Z.; Nunes, P.A.; Lopes, A.I. Avaliação da Ingestão Alimentar de Crianças e Jovens Internados no Departamento de Pediatria. Newsl. TDT 2013. Available online: http://www.chln.pt/media/k2/attachments/newstdt/News_TDT_12.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Nichols, P.J.; Porter, C.; Hammond, L.; Arjmandi, B.H. Food Intake may be Determined by Plate Waste in a Retirement Living Center. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1142–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yngve, A.; Wolf, A.; Poortvliet, E.; Elmadfa, I.; Brug, J.; Ehrenblad, B.; Franchini, B.; Haraldsdóttir, J.; Krølner, R.; Maes, L.; et al. Fruit and vegetable intake in a sample of 11-year-old children in 9 European countries: The Pro Children Cross-sectional Survey. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2005, 49, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holdt, C.S.; Sitter, K.; Gates, G.E. Comparison of plate waste estimation measures in a pediatric hospital. Foodserv. Res. Int. 1993, 7, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marson, H.; McErlain, L.; Ainsworth, P. The implications of food wastage on a renal ward. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frakes, E.M.; Arjmandi, B.H.; Halling, J.F. Plate waste in a hospital cook-freeze production system. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1986, 86, 941–942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marinho, R.; Lopes, M.; Pessoa, A.; Rosinhas, J.; Pinho, J.; Silveira, J.; Amado, A.; Silva, S.; Oliveira, B.; Marinho, A. Malnutrition in Portuguese internal medicine wards: Multi-center prevalence study. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 37, S239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, A.; Lopes, A.; Sousa, G.; Antunes, H.; Fonseca, J.; Mendes, L.; Carvalho, M.D.; Veríssimo, M.T.; Carvalho, N.; Alves, P.; et al. A Malnutrição Associada à Doença e as suas Repercussões em Portugal. Med. Int. 2019, 26, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).