Determinants of Dollarization of Savings in the Turkish Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methodology

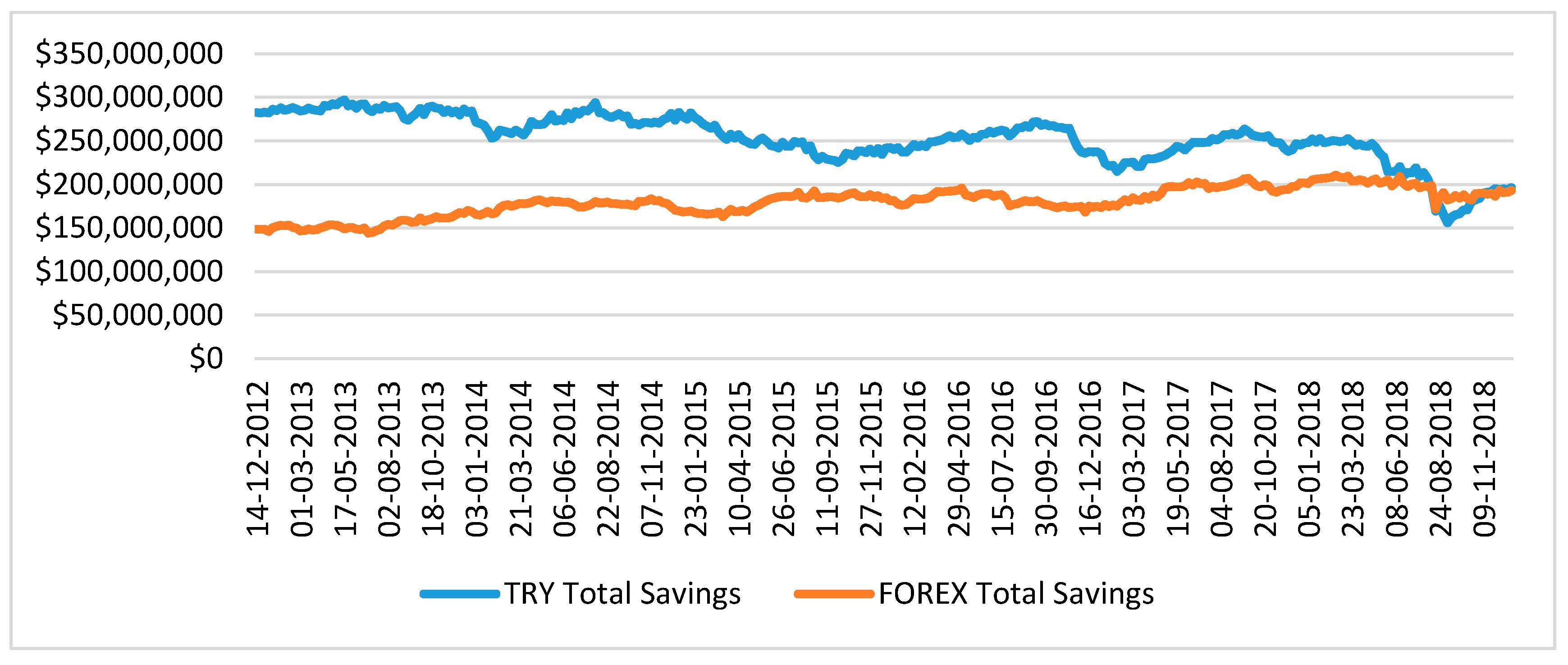

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Research Methodology

3.2.1. Methodology of Cointegration Analysis

3.2.2. Methodology of the Vector Error Correction Model

4. Research Results

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Işik, S. Dollarization and Bank Performance. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Middle East Technical University. 2019. Available online: http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12624321/index.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Arteta, C.O. Exchange rate regimes and financial dollarization: Does flexibility reduce currency mismatches in bank intermediation? BE J. Macroecon. 2005, 5, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelried, D.; Castillo, P. Dollarization persistence and individual heterogeneity. J. Int. Money Financ. 2010, 29, 1596–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Koc, C. Turkey’s Albayrak Says Jobs Prioritized Over Fiscal Discipline. Bloomberg.Com, 5 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- GÜRGÜN, G. Estimating Effects of Uncertainty on the Turkish Economy; Akdeniz University Faculty of Economics & Administrative Sciences Faculty Journal/Akdeniz Universitesi Iktisadi ve Idari Bilimler Fakultesi Dergisi: Antalya, Turkey, 2019; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. Turkey’s Erdogan Fires Central Bank Governor. BBC News, 6 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Demiralp, S.; Selva, D. Erosion of Central Bank Independence in Turkey. Turk. Stud. 2019, 20, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglayan, M.; Oleksandr, T. Dollarization, Liquidity and Performance: Evidence from Turkish Banking, MPRA Paper No. 72812. 2016. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/72812/ (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Bannister, G.J.; Turunen, J.; Gardberg, M. Dollarization and Financial Development; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ybrayev, Z. Monetary Policy under Financial Dollarization: The Case of the Eurasian Economic Union, The Political Economy of International Finance in an Age of Inequality; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, A. Are CDS Spreads Sensitive to the Term Structure of the Yield Curve? A Sector-Wise Analysis under Various Market Conditions. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2019, 12, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A.E.; Teixeira, J.F. The Formation of New Monetary Policies: Decisions of Central Banks on the Great Recession. Economies 2014, 2, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, F.; Gruppe, M. Performance of Survey Forecasts by Professional Analysts: Did the European Debt Crisis Make It Harder or Perhaps Even Easier? Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, O. Socio-Political Unrest and Its Impact on the Turkish Economy and Investment Strategies; University of Politecnico Milano: Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.A. The Implications of ICT in Surviving a Coup d’État for a Popular Regime; Baylor University: Texas, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Çağatay, O.; Bayraklı, E. Understanding Ever-Changing Dynamics in Turkish-EU Relations during the AK Party Era (2002–2018). Mukaddime 2019, 10, 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Fouskas, V.K.; Bülent, G. Placing the USA–Turkey Standoff in Context: The USA and the Weaponization of Global Finance. J. Glob. Faultlines 2018, 5, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.W. Dollarization and trade. J. Int. Money Financ. 2005, 24, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamin, S.B.; Ericsson, N.R. Dollarization in Argentina, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, International Finance Discussion Papers, No. 460. 1993; pp. 1–56. Available online: https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/1993/460/ifdp460.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2020).

- Neanidis, K.C.; Savva, C.S. Financial dollarization: Short-run determinants in transition economies. J. Bank. Financ. 2009, 33, 1860–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, G.A. Testimony on Dollarization. Presented at the before the Subcommittee on Domestic and Monetary Policy, Committee on Banking and Financial Services, Washington, DC, USA, 22 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Levy-Yeyati, E.; Sturzenegger, F. Dollarization: A primer. In Dollarization; Levy-Yeyati, E., Sturzenegger, F., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, R. Exploring the Implications of Official Dollarization on Macroeconomic Volatility; Working Papers No. 200; Central Bank of Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2003; pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, A.; Borensztein, E. The pros and Cons of Full Dollarization; Working Paper (WP/00/50); International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2000/wp0050.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Ajide, K.; Raheem, I.; Asongu, S. Dollarization and the “unbundling” of globalization in sub-Saharan Africa. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 47, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicolo, G.; Honohan, P.; Ize, A. Dollarization of bank deposits: Causes and consequences. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1697–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikwila, M.N. Dollarization and the Zimbabwe’s Economy. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2013, 5, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, J. Cambodia’s persistent dollarization: Causes and policy options. ASEAN Econ. Bull. 2008, 25, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Berkmen, P.; Cavallo, E. Exchange rate policy and liability dollarization: What do the data reveal about causality? Rev. Int. Econ. 2010, 18, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quispe-Agnoli, M. Official Dollarization and the Banking System in Ecuador and El Salvador. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Economic Review. 2006, pp. 55–71. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4977/8ce6879644896bf67929b4d8ad99b8350bc6.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Debelle, G. Central Bank Independence: A free Lunch? Working Paper No. 96/1; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, D. Monetary policy in emerging markets: Can liability dollarization explain contractionary devaluations? J. Monet. Econ. 2004, 51, 1155–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ize, M.A. Spending Seigniorage: Do Central Banks Have a Governance Problem? Working Paper No. 06/58; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baltensperger, E.; Jordan, T.J. Seigniorage and the transfer of central bank profits to the government. Kyklos 1998, 51, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazen, A. A general measure of inflation tax revenues. Econ. Lett. 1985, 17, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukierman, A.; Edwards, S.; Tabellini, G. Seigniorage and political instability. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 82, 537–555. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, F. Unanticipated inflation and government finance: The case for an independent common central bank. CentER Discuss. Pap. 1991, 15, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, C.; Sauer, C. Dollarization in Latin America: Seigniorage costs and policy implications. The Quarterly Rev. Econ. Financ. 2005, 45, 662–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh, S.A.P.; Udeaja, E.A. Asymmetric effects of financial dollarization on nominal exchange rate volatility in Nigeria. J. Econ. Asymmetries 2019, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichengreen, B.; Hausmann, R. Other People’s Money: Debt Denomination and Financial Instability Emerging Market Economies; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eichengreen, B.; Hausmann, R. Exchange Rates and Financial Fragility; NBER Working Papers 7418; National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 329–368. [Google Scholar]

- Mecagni, M.; Corrales, S.; Dridi, J.; Garcia-Verdu, R.; Imam, P.; Matz, J. Dollarization is SSA: Experience and Lessons; IMF: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jacome, L.I.; Lonnberg, A. Implementing Official Dollarization; Working Paper (WP/10/106); International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/Implementing-Official-Dollarization-23800 (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Licandro, G.; Mello, M. Cultural and Financial Dollarization of Households in Uruguay; Paper 009; Banco Central del Uruguay: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2017; pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kokenyne, A.; Ley, J.; Veyrune, R. De-Dollarization; Working Paper No. WP/10/188; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Escribano, M. Peru: Drivers of de-Dollarisation; Working Paper No. WP/10/169; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kamin, S.B.; Ericsson, N.R. Dollarization in post-hyperinflationary Argentina. J. Int. Money Financ. 2003, 22, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdaroğlu, T. Financial Dollarization in the Turkish Economy: “The Portfolio View”. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, September 2011. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.632.9207&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Brodsky, B. Dollarization and Monetary Policy in Russia. Rev. Econ. Transit. 1997, 6, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Financial Accounts Report. Available online: http://www.tcmb.gov.tr/wps/wcm/connect/EN/TCMB+EN/Main+Menu/Publications/Reports/Financial+Accounts+Report/ (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- Inclan, C.; George, C. Tiao Use of Cumulative Sums of Squares for Retrospective Detection of Changes of Variance. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1994, 89, 913–923. [Google Scholar]

- Berglöf, E.; Thadden von, E.L. Short-Term versus Long-Term Interests: Capital Structure with Multiple Investors. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 1055–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürkaynak, R.S.; Sack, B.; Swanson, E. The Sensitivity of Long-Term Interest Rates to Economic News: Evidence and Implications for Macroeconomic Models. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, K.; Wiklund, J.; Hellerstedt, K.; Nordqvist, M. Implications of Intra-family and External Ownership Transfer of Family Firms: Short-term and Long-term Performance Differences. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2011, 5, 352–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.H. Econometric Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, W. Applied Econometric Time Series; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, P.; Thi, H. Zero Interest Rate for the US Dollar Deposit and Dollarization: The Case of Vietnam. In International Econometric Conference of Vietnam; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 792–809. [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman, P.; Solimano, A. Crisis and dollarization. In Ecuador: Stability, Growth, and Social Equity; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Çalışkan, A.; Karimova, A. Global Liquidity, Current Account Deficit, and Exchange Rate Balance Sheet Effects in Turkey. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2017, 53, 1619–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamollaoğlu, N.; Yalçin, C. Exports, Real Exchange Rates and Dollarization: Empirical Evidence from Turkish Manufacturing Firms. Empir. Econ. 2019, 1, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, K. Dollarization and De-Dollarization in Transitional Economies of Southeast Asia: An Overview, Dollarization and De-dollarization. In Transitional Economies of Southeast Asia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Licandro, G.; Mello, M. Cultural and Financial Dollarization of Households in Uruguay, Financial Decisions of Households and Financial Inclusion: Evidence for Latin America and the Caribbean; Journal of Applied Economics: London, United Kingdom, 2016; p. 349. [Google Scholar]

- Marcelin, I.; Ike, M. Financial Sector Development and Dollarization in Emerging Economies. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2016, 46, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin-Özcan, K.; Us, V. Dedollarization in Turkey after decades of dollarization: A myth or reality? Phys. A 2007, 385, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidhiprabha, B. Economic Growth, Monetary Policy, and Dollarization in CLMV Countries, Dollarization and De-dollarization in Transitional Economies of Southeast Asia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 167–196. [Google Scholar]

- Odajima, K. Dollarization in Cambodia: Behavior of Households and Enterprises in a Highly Dollarized Environment. In Dollarization and De-dollarization in Transitional Economies of Southeast Asia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 33–72. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, H. Banking and Dollarization: A Comparative Study of Cambodia, Lao PDR, and Vietnam. Dollarization and De-dollarization in Transitional Economies of Southeast Asia; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 197–237. [Google Scholar]

- Ozsoz, E.; Rengifo, E. Understanding Dollarization: Causes and Impact of Partial Dollarization on Developing and Emerging Markets; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tasseven, O. The relationship between economic development and female labor force participation rate: A panel data analysis. In Global Financial Crisis and Its Ramifications on Capital Markets; Springer: Cham, Turkey, 2017; pp. 555–568. [Google Scholar]

- Urosevic, B.; Rajkovic, I. Dollarization of Deposits in the Short and Long Run: Evidence from CESE Countries. Panoeconomicus 2016, 64, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Breakpoint | ICSS | MS-Dynamic |

|---|---|---|

| Dollarization | 15.7.2016 | 15.7.2016 |

| Try/Usd Rate | 14.9.2018 | 2018-11-16 |

| Research Question | Test Criterion | Methodology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| P | What are the significant events that affected the dollarization trend in Turkey? | Significant shifts in variance trends are expected to be observed at the break dates. | ICSS algorithm and MS-DR methods are used to analyze the breaking points. |

| 1 | Is the arbitrage due to yield differences between currencies the reason for dollarization? | A negative and persistent relation between TRY interest rates and dollarization is expected. | Using the Johansen cointegration test, at least two cointegrated vectors between variables are found, followed by the Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) to differentiate short-term and long-term relationships between the variables. |

| 2 | Are central bank policies effective? | Short-term negative effects of central bank policies on dollarization are expected to persist or at least not to revert in the long term. | |

| 3 | Do investors trust in the consistency of monetary policy? | Both interest rate and exchange rate are expected to have two-way causality with dollarization. | Granger causality test is used to determine the relationship between dollarization and exchange rate or interest rates. |

| Dollarization | Domestic (Forex Deposits/Total Deposits) |

|---|---|

| Dollarer | Exchange rate of TRY per USD |

| Interesteur | Interest rate of EUR for the given date |

| Interesttry | Interest rate of TRY for the given date |

| Interestusd | Interest rate of USD for the given date |

| ADF | KPSS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | Constant and Trend | Constant | Constant and Trend | |

| dollarization | −1.4887 (2) | −2.8959 (2) | 1.8625 (4) *** | 0.2146 (4) *** |

| ∆dollarization | −9.9068 (2) *** | −9.8879 (2) *** | 0.0772 (14) | 0.0625 (14) |

| dollarer | 0.088570 (12) | −2.748859 (12) | 2.102340 (15) *** | 0.182841 (15) ** |

| ∆dollarer | −4.255781 (16) *** | −4.280110 (16) *** | 0.082056 (8) | 0.028351 (8) |

| interesteur | −1.7753 (7) | −2.6154 (7) | 1.2058 (15) *** | 0.3729 (15) *** |

| ∆interesteur | −6.9098 (6) *** | −6.8981 (6) *** | 0.0637 (10) | 0.0515 (10) |

| İnteresttry | −0.2289 (10) | −1.8458 (10) | 1.5577 (15) *** | 0.3040 (15) *** |

| ∆interesttry | −3.9975 (10) *** | −4.5354 (10) *** | 0.1885 (10) | 0.0463 (10) |

| İnterestusd | 1.7498 (5) | −2.5096 (5) | 1.1846 (15) *** | 0.3841 (15) *** |

| ∆interestusd | −7.7180 (4) *** | −7.7094 (4) *** | 0.0777 (6) | 0.0630 (6) |

| Critical Values | 1% −3.4497 5% −2.8700 10% −2.5713 | 1% −3.9858 5% −3.4233 10% −3.1346 | 1% 0.7390 5% 0.4630 10% 0.3470 | 1% 0.2160 5% 0.1460 10% 0.1190 |

| Hypothesized | Trace | 0.05 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of CE(s) | Eigenvalue | Statistic | Critical Value | Prob. ** |

| None * | 0.155249 | 128.8402 | 69.81889 | 0.0000 |

| At most 1 * | 0.140752 | 72.65847 | 47.85613 | 0.0001 |

| At most 2 | 0.040710 | 22.14303 | 29.79707 | 0.2906 |

| At most 3 | 0.020830 | 8.302828 | 15.49471 | 0.4336 |

| At most 4 | 0.003876 | 1.293073 | 3.841466 | 0.2555 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDOLLARER | −0.089043 | 0.022624 | −3.935719 | * 0.0001 |

| INTERESTEUR | 0.036536 | 0.009290 | 3.932660 | * 0.0001 |

| INTERESTTRY | 0.006188 | 0.001253 | 4.938988 | * 0.0000 |

| INTERESTUSD | −0.053514 | 0.006601 | −8.107233 | * 0.0000 |

| C | 0.370643 | 0.018462 | 20.07565 | * 0.0000 |

| R-squared | 0.894209 | Akaike info criterion | −5.343168 | |

| F-statistic | 699.4523 | Schwarz criterion | −5.286366 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 * | Durbin–Watson stat | 0.266608 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D(LDOLLARER) | −0.112564 | 0.019399 | −5.802672 | * 0.0000 |

| D(INTERESTEUR) | 0.000524 | 0.004425 | 0.118436 | 0.9058 |

| D(INTERESTTRY) | 0.002763 | 0.001304 | 2.118291 | ** 0.0349 |

| D(INTERESTUSD) | −0.004797 | 0.002565 | −1.870718 | *** 0.0623 |

| EC(-1) | −0.085310 | 0.022280 | −3.828922 | * 0.0002 |

| C | 0.00000913 | 0.000406 | 0.224642 | 0.8224 |

| R-squared | 0.120569 | Akaike info criterion | −7.329646 | |

| F-statistic | 9.021073 | Schwarz criterion | −7.261333 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.000000 | Durbin–Watson stat | 1.944110 | |

| Dependent Variable: D (DOLLARIZATION) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Excluded | Chi-sq | Df | Prob. |

| D (LDOLLARER) | 6.8417 | 2 | ** 0.0296 |

| D (INTERESTEUR) | 5.516703 | 2 | *** 0.0634 |

| D (INTERESTTRY) | 8.318193 | 2 | ** 0.0156 |

| D (INTERESTUSD) | 1.248287 | 2 | 0.5357 |

| Dependent Variable: D (LDOLLARER) | |||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D (DOLLARIZATION) | 22.60628 | 3 | * 0.0000 |

| D (INTERESTEUR) | 5.043102 | 3 | 0.1687 |

| D (INTERESTTRY) | 16.17557 | 3 | * 0.0010 |

| D (INTERESTUSD) | 0.729735 | 3 | 0.8662 |

| Dependent Variable: D (INTERESTEUR) | |||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D (LDOLLARER) | 29.9051 | 2 | * 0.0000 |

| D (DOLLARIZATION) | 2.300444 | 2 | 0.3166 |

| D (INTERESTTRY) | 29.96001 | 2 | * 0.0000 |

| D (INTERESTUSD) | 15.72765 | 2 | * 0.0004 |

| Dependent Variable: D (INTERESTTRY) | |||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D (LDOLLARER) | 66.9005 | 2 | * 0.0012 |

| D (DOLLARIZATION) | 1.862886 | 2 | 0.3940 |

| D (INTERESTEUR) | 16.89594 | 2 | * 0.0002 |

| D (INTERESTUSD) | 19.33189 | 2 | * 0.0001 |

| Dependent Variable: D (INTERESTUSD) | |||

| Excluded | Chi-sq | df | Prob. |

| D (LDOLLARER) | 7.6532 | 2 | *** 0.0537 |

| D (DOLLARIZATION) | 0.797250 | 2 | 0.6712 |

| D (INTERESTEUR) | 7.928535 | 2 | ** 0.0190 |

| D (INTERESTTRY) | 18.30018 | 2 | * 0.0001 |

| Research Question | Test Criterion | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Is the arbitrage due to yield differences between currencies the reason for dollarization? | A negative and persistent relation between TRY interest rates and dollarization is expected. | A positive relationship between the TRY interest rate and dollarization was found in the short term, while the USD interest rate has a negative effect. |

| 2 | Are central bank policies effective? | Short-term negative effects of central bank policies on dollarization are expected to persist or at least not to revert in the long term. | The positive relationship persists in the long run, with the addition of the EUR interest rate with a negative effect on dollarization. |

| 3 | Do investors trust in the consistency of monetary policy? | Both interest rate and exchange rate are expected to have two-way causality with dollarization. | The exchange rate has two-way causality while interest rates have one-way causality. |

| (Author Date) | Country | Contradictory | Complementary |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Anh 2018) [57] | Vietnam | X | |

| (Bannister et al. 2018) [9] | Emerging Markets | X | X |

| (Caglayan and Talavera 2016) [8] | Turkey | X | X |

| (Beckerman and Solimano 2002) [58] | Ecuador | X | |

| (Çalışkan and Karimova 2017) [59] | Turkey | X | |

| (IŞIK 2019) [1] | Turkey | X | |

| (Karamollaoğlu and Yalçin 2019) [60] | Turkey | X | |

| (Kubo 2017) [61] | ASEAN | X | |

| (Licandro and Mello 2016) [62] | Latin America | X | X |

| (Marcelin and Mathur 2016) [62] | Turkey + 19 Countries | X | |

| (Marcelin and Ike 2018) [63] | Emerging Economies | X | |

| (Metin-Özcan 2017) [64] | Turkey | X | |

| (Nidhiprabha 2017) [65] | CLMV Countries | X | X |

| (Odajima 2017) [66] | ASEAN | X | |

| (Okuda 2017) [67] | Cambodia | X | |

| (Ozsoz and Rengifo 2016) [68] | Emerging Markets | X | |

| (Tasseven 2017) [69] | Turkey | X | |

| (Urosevic and Rajkovic 2016) [70] | CESE Countries | X | |

| (Ybrayev 2018) [10] | ASEAN | X | X |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bărbuță-Mișu, N.; Güleç, T.C.; Duramaz, S.; Virlanuta, F.O. Determinants of Dollarization of Savings in the Turkish Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156141

Bărbuță-Mișu N, Güleç TC, Duramaz S, Virlanuta FO. Determinants of Dollarization of Savings in the Turkish Economy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):6141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156141

Chicago/Turabian StyleBărbuță-Mișu, Nicoleta, Tuna Can Güleç, Selim Duramaz, and Florina Oana Virlanuta. 2020. "Determinants of Dollarization of Savings in the Turkish Economy" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 6141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156141

APA StyleBărbuță-Mișu, N., Güleç, T. C., Duramaz, S., & Virlanuta, F. O. (2020). Determinants of Dollarization of Savings in the Turkish Economy. Sustainability, 12(15), 6141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12156141