Sustainability in Business Process Management as an Important Strategic Challenge in Human Resource Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Empirical Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Gender | Age | Job Category | Mean | {1} | {2} | {3} | {4} | {5} | {6} | {7} | {8} | {9} | {10} | {11} | {12} | {13} | {14} | {15} | {16} | {17} | {18} | {19} | {20} | {21} | {22} | {23} | {24} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.466 | 4.343 | 4.454 | 4.489 | 4.350 | 4.423 | 4.443 | 4.320 | 4.393 | 4.466 | 4.321 | 4.447 | 4.528 | 4.422 | 4.551 | 4.534 | 4.407 | 4.522 | 4.492 | 4.428 | 4.524 | 4.457 | 4.403 | 4.566 | ||||

| Male | <30 | Manager | {1} | 0.935 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.966 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.734 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.744 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.994 | |

| BCW | {2} | 0.935 | 0.073 | 0.119 | 1.000 | 0.319 | 0.776 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.859 | 1.000 | 0.586 | 0.114 | 0.189 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.445 | 0.000 | 0.136 | 0.046 | 0.000 | 0.961 | 0.958 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {3} | 1.000 | 0.073 | 1.000 | 0.145 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.005 | 0.962 | 1.000 | 0.006 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.242 | 0.980 | 0.999 | 0.893 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.858 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.065 | |||

| <40 | Manager | {4} | 1.000 | 0.119 | 1.000 | 0.188 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.021 | 0.866 | 1.000 | 0.022 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.972 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.954 | 0.986 | ||

| BCW | {5} | 0.966 | 1.000 | 0.145 | 0.188 | 0.525 | 0.877 | 0.997 | 1.000 | 0.918 | 1.000 | 0.729 | 0.166 | 0.370 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.702 | 0.000 | 0.210 | 0.124 | 0.000 | 0.982 | 0.991 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {6} | 1.000 | 0.319 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.525 | 1.000 | 0.028 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.031 | 1.000 | 0.968 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.656 | 1.000 | 0.050 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.037 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| <50 | Manager | {7} | 1.000 | 0.776 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.877 | 1.000 | 0.360 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.374 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.644 | 0.925 | 1.000 | 0.978 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.969 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.369 | ||

| BCW | {8} | 0.734 | 1.000 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.997 | 0.028 | 0.360 | 0.805 | 0.567 | 1.000 | 0.188 | 0.030 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.027 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.794 | 0.513 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {9} | 1.000 | 0.997 | 0.962 | 0.866 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.805 | 1.000 | 0.822 | 1.000 | 0.704 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 1.000 | 0.009 | 0.868 | 1.000 | 0.007 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| 50+ | Manager | {10} | 1.000 | 0.859 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.918 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.567 | 1.000 | 0.579 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.985 | ||

| BCW | {11} | 0.744 | 1.000 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 1.000 | 0.031 | 0.374 | 1.000 | 0.822 | 0.579 | 0.199 | 0.031 | 0.021 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.009 | 0.000 | 0.803 | 0.534 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {12} | 1.000 | 0.586 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.729 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.188 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.199 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.603 | 0.954 | 1.000 | 0.976 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.967 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.318 | |||

| Female | <30 | Manager | {13} | 1.000 | 0.114 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.166 | 0.968 | 0.998 | 0.030 | 0.704 | 1.000 | 0.031 | 0.999 | 0.964 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.867 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.830 | 1.000 | |

| BCW | {14} | 1.000 | 0.189 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.370 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.021 | 1.000 | 0.964 | 0.000 | 0.636 | 1.000 | 0.013 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {15} | 0.990 | 0.000 | 0.242 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.644 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.000 | 0.603 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |||

| <40 | Manager | {16} | 1.000 | 0.003 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.007 | 0.656 | 0.925 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.954 | 1.000 | 0.636 | 1.000 | 0.363 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.732 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.304 | 1.000 | ||

| BCW | {17} | 1.000 | 0.445 | 0.999 | 0.972 | 0.702 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.029 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.142 | 1.000 | 0.867 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.363 | 0.000 | 0.970 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {18} | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.893 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.978 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.976 | 1.000 | 0.013 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.010 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.023 | 0.995 | |||

| <50 | Manager | {19} | 1.000 | 0.136 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.210 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 0.027 | 0.868 | 1.000 | 0.029 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.970 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.953 | 0.996 | ||

| BCW | {20} | 1.000 | 0.046 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.124 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 0.980 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.732 | 1.000 | 0.010 | 0.999 | 0.007 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {21} | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.858 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.037 | 0.969 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.967 | 1.000 | 0.009 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.007 | 1.000 | 0.017 | 0.998 | |||

| 50+ | Manager | {22} | 1.000 | 0.961 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.982 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.794 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.803 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.975 | ||

| BCW | {23} | 1.000 | 0.958 | 0.996 | 0.954 | 0.991 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.513 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.534 | 1.000 | 0.830 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.304 | 1.000 | 0.023 | 0.953 | 1.000 | 0.017 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {24} | 0.994 | 0.000 | 0.065 | 0.986 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.369 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.985 | 0.000 | 0.318 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.000 | 0.998 | 0.975 | 0.000 |

| Gender | Age | Job Category | Mean | {1} | {2} | {3} | {4} | {5} | {6} | {7} | {8} | {9} | {10} | {11} | {12} | {13} | {14} | {15} | {16} | {17} | {18} | {19} | {20} | {21} | {22} | {23} | {24} |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.469 | 4.321 | 4.439 | 4.458 | 4.338 | 4.393 | 4.482 | 4.305 | 4.417 | 4.458 | 4.296 | 4.417 | 4.558 | 4.421 | 4.534 | 4.493 | 4.410 | 4.524 | 4.507 | 4.426 | 4.503 | 4.573 | 4.389 | 4.531 | ||||

| Male | <30 | Manager | {1} | 0.761 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.910 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.559 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.446 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.993 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| BCW | {2} | 0.761 | 0.053 | 0.253 | 1.000 | 0.617 | 0.044 | 1.000 | 0.309 | 0.755 | 1.000 | 0.793 | 0.007 | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.888 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {3} | 1.000 | 0.053 | 1.000 | 0.232 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.003 | 1.000 | 0.915 | 1.000 | 0.330 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.575 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.956 | 0.858 | 0.998 | 0.410 | |||

| <40 | Manager | {4} | 1.000 | 0.253 | 1.000 | 0.524 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.096 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.052 | 1.000 | 0.988 | 1.000 | 0.992 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.969 | 0.998 | 0.996 | ||

| BCW | {5} | 0.910 | 1.000 | 0.232 | 0.524 | 0.954 | 0.144 | 0.994 | 0.709 | 0.915 | 0.998 | 0.964 | 0.021 | 0.163 | 0.000 | 0.101 | 0.247 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.995 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {6} | 1.000 | 0.617 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.954 | 0.938 | 0.202 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.084 | 1.000 | 0.357 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.872 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.717 | 1.000 | 0.018 | 0.304 | 1.000 | 0.000 | |||

| <50 | Manager | {7} | 1.000 | 0.044 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.144 | 0.938 | 0.011 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.005 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.911 | 1.000 | ||

| BCW | {8} | 0.559 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.096 | 0.994 | 0.202 | 0.011 | 0.083 | 0.534 | 1.000 | 0.490 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.533 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {9} | 1.000 | 0.309 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.709 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.083 | 1.000 | 0.034 | 1.000 | 0.696 | 1.000 | 0.055 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.143 | 0.966 | 1.000 | 0.576 | 0.615 | 1.000 | 0.078 | |||

| 50+ | Manager | {10} | 1.000 | 0.755 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.915 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.534 | 1.000 | 0.412 | 1.000 | 0.990 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.969 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| BCW | {11} | 0.446 | 1.000 | 0.003 | 0.052 | 0.998 | 0.084 | 0.005 | 1.000 | 0.034 | 0.412 | 0.330 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.323 | 0.000 | |||

| WCW | {12} | 1.000 | 0.793 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.964 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.490 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.330 | 0.695 | 1.000 | 0.406 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.606 | 0.965 | 1.000 | 0.927 | 0.613 | 1.000 | 0.474 | |||

| Female | <30 | Manager | {13} | 0.999 | 0.007 | 0.915 | 0.988 | 0.021 | 0.357 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.696 | 0.990 | 0.001 | 0.695 | 0.741 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.600 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.798 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.315 | 1.000 | |

| BCW | {14} | 1.000 | 0.020 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.163 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.741 | 0.008 | 0.997 | 1.000 | 0.012 | 0.978 | 1.000 | 0.189 | 0.660 | 1.000 | 0.015 | |||

| WCW | {15} | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.330 | 0.992 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.406 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.016 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | |||

| <40 | Manager | {16} | 1.000 | 0.030 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.101 | 0.872 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.003 | 0.994 | 1.000 | 0.997 | 1.000 | 0.982 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.831 | 1.000 | ||

| BCW | {17} | 1.000 | 0.029 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.247 | 1.000 | 0.996 | 0.002 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.005 | 1.000 | 0.600 | 1.000 | 0.002 | 0.982 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 1.000 | 0.020 | 0.522 | 1.000 | 0.003 | |||

| WCW | {18} | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.575 | 0.999 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.143 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.606 | 1.000 | 0.012 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.005 | 1.000 | |||

| <50 | Manager | {19} | 1.000 | 0.014 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.051 | 0.717 | 1.000 | 0.003 | 0.966 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.965 | 1.000 | 0.978 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.926 | 1.000 | 0.989 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.661 | 1.000 | ||

| BCW | {20} | 1.000 | 0.003 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.043 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.798 | 1.000 | 0.016 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 0.008 | 0.989 | 0.172 | 0.720 | 1.000 | 0.029 | |||

| WCW | {21} | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.956 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.576 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.927 | 1.000 | 0.189 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.020 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.172 | 1.000 | 0.063 | 1.000 | |||

| 50+ | Manager | {22} | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.858 | 0.969 | 0.020 | 0.304 | 0.998 | 0.002 | 0.615 | 0.969 | 0.001 | 0.613 | 1.000 | 0.660 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.522 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.720 | 1.000 | 0.268 | 1.000 | ||

| BCW | {23} | 1.000 | 0.888 | 0.998 | 0.998 | 0.995 | 1.000 | 0.911 | 0.533 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.323 | 1.000 | 0.315 | 1.000 | 0.001 | 0.831 | 1.000 | 0.005 | 0.661 | 1.000 | 0.063 | 0.268 | 0.002 | |||

| WCW | {24} | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.410 | 0.996 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.078 | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.474 | 1.000 | 0.015 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.003 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.029 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.002 |

References

- Laužikas, M.; Miliūtė, A. Impacts of modern technologies on sustainable communication of civil service organizations. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2494–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogodina, T.V.; Muzhzhavleva, T.V.; Udaltsova, N.L. Strategic management of the competitiveness of industrial companies in an unstable economy. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohnová, L.; Papula, J.; Salajová, N. Internal factors supporting business and technological transformation in the context of industry 4.0. Bus. Theory Pract. 2019, 20, 137–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedeliaková, E.; Kuka, A.; Sulko, P.; Hranický, M. An Innovative Approach to Monitoring the Synergies of Extraordinary Events in Rail Transport. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Scientific on Conference Transport Means 2018, Trakai Resort and SPAGedimino, Trakai, Lithuania, 3–5 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bajzikova, L.; Novackova, D.; Saxunova, D. Globalization in the Case of Automobile Industry in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 30th International Business Information Management Association Conference, IBIMA 2017–Vision 2020: Sustainable Economic development, Innovation Management, and Global Growth, Madrid, Spain, 8–9 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stacho, Z.; Stachova, K. Outplacement as Part of Human Resource Management. In Proceedings of the 9th International Scientific Conference on Business Economics and Management, Izmir, Turkey, 15–16 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nyvlt, V. The Role of Managing Knowledge and Information in BIM Implementation Processes in the Czech Republic. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Building Defects, Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic, 29–30 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Štarchoň, P.; Weberová, D.; Ližbetinová, L. Clustering Czech Consumers According to their Spontaneous Awareness of Foreign Brands. In Proceedings of the 29th International Business Information Management Association Conference Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Vienna, Austria, 3–4 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, C.; De Cieri, H.; Cooper, B.; Shea, T. Strategic implications of HR role management in a dynamic environment. Pers. Rev. 2016, 45, 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbancova, H.; Vnouckova, L.; Laboutkova, S. Knowledge transfer in a knowledge-based economy. E M Ekon. A Manag. 2016, 19, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palus, H.; Parobek, J.; Dzian, M.; Simo-Svrcek, S.; Krahulcova, M. How companies in the wood supply chain perceive the forest certification. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2019, 61, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaľová, M.; Hvolková, L.; Klement, L.; Klementová, V. Innovation strategies in the Slovak enterprises. Acta Oeconomica Univ. Selye 2018, 7, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Weberová, D.; Ližbetinová, L. Consumer Attitudes Towards Brands in Relation to Price. In Proceedings of the 27th International Business Information Management Association Conference Innovation Management and Education Excellence Vision 2020 from Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Milan, Italy, 4–5 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kleprlík, J.; Talácko, V. Possibilities how to solve the insufficient number of professional drivers. Perner’s Contacts 2019, 19, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, N. SME Internationalization Strategies: Innovation to Conquer New Markets; Wiley Backwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nemec, M.; Kristak, L.; Hockicko, P.; Danihelova, Z.; Velmovska, K. Application of innovative P&E method at technical universities in Slovakia. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2017, 13, 2329–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graa, A.; Abdelhak, S. A review of branding strategy for small and medium enterprises. Acta Oeconomica Univ. Selye 2016, 5, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, H.S.; Seo, K.H.; Yoon, H.H. The importance of leader integrity on family restaurant employees’ engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors: Exploring sustainability of employees’ generational differences. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kucharčíková, A.; Mičiak, M. Human capital management in transport enterprises with the acceptance of sustainable development in the Slovak Republic. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stankevičiūté, Ž.; Savanevičiené, A. Designing sustainable HRM: The core characteristics of emerging field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szierbowski-Seibel, K. Strategic human resource management and its impact on performance—Do Chinese organizations adopt appropriate HRM policies? J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 9, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacho, Z.; Stachova, K. The Extent of Education of Employees in Organisations Operating in Slovakia. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Efficiency and Responsibility in Education, Prague, Czech Republic, 4–5 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kropivšek, J.; Jelačić, D.; Grošelj, P. Motivating employees of Slovenian and Croatian wood-industry companies in times of economic downturn. Drv. Ind. 2011, 62, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborova, E.; Markova, T. Human Capital as a Factor of Regional Development. In Proceedings of the 12th International Days of Statistics and Economics, Prague, Czech Republic, 6–8 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stachova, K.; Stacho, Z.; Blstakova, J.; Hlatká, M.; Kapustina, L.M. Motivation of employees for creativity as a form of support to manage innovation processes in transportation-logistics companies. Nase More 2018, 65, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sellero, M.C.; Sánchez-Sellero, P.; Cruz-González, M.M.; Sánchez-Sellero, F.J. Determinants of job satisfaction in the spanish wood and paper industries: A comparative study across spain. Drv. Ind. 2018, 69, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R. How to Motivate Employees; Psychology Today: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- David, A.; Anderzej, A. Organisational Behavior, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, Z.; Hollósy, V.G. The revision of Hungarian public service motivation (PSM) model. Cent. Eur. J. Labour Law Pers. Manag. 2019, 2, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kontodimopoulos, N.; Paleologou, V.; Niakas, D. Identifying important motivational factors for professionals in Greek hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009, 9, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halbesleben, J.R.B.; Bowler, W.M. Emotional exhaustion and job performance: The mediating role of motivation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, M.R.; Stewart, G.L.; Piotrowski, M. Personality and job performance: Test of the mediating effects of motivation among sales representatives. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kimengsi, J.N.; Bhusal, P.; Aryal, A.; Fernandez, M.V.B.C.; Owusu, R.; Chaudhary, A.; Nielsen, W. What (de) motivates forest users’ participation in co-management? Evidence from Nepal. Forests 2019, 10, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brady, P.Q.; King, W.R. Brass satisfaction: Identifying the personal and work-related factors associated with job satisfaction among police chiefs. Police Q. 2018, 21, 250–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, S.K.; Kazemi, A. Identifying and ranking factors affecting motivation of employees. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 2418–2423. [Google Scholar]

- Damij, N.; Levnajić, Z.; Skrt, V.R.; Suklan, J. What motivates us for work? Intricate web of factors beyond money and prestige. PLoS ONE 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Rana, M.S.; Lone, A.H.; Maqbool, S.; Naz, K.; Ali, A. Teacher’s competencies and factors affecting the performance of female teachers in Bahawalpur (Southern Punjab) Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chatzopoulou, M.; Vlachvei, A.; Monovasilis, T. Employee’s motivation and satisfaction in light of economic recession: Evidence of Grevena Prefecture-Greece. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 24, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kampkötter, P. Performance appraisals and job satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 28, 750–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelov, K.; Stoyanova, T.; Tamošiūnienė, R. Research of motivation of employees in the it sector in Bulgaria. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 7, 2556–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakotic, D.; Babic, T.B. Relationship between working conditions and job satisfaction: The case of Croatian shipbuilding company. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 206–213. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, Q.A. Impact of employees’ motivation on organizational effectiveness. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, E.; Harris, L.C. Leadership style, organizational culture and performance: Empirical evidence from UK companies. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 766–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, A.; Maulabakhsh, R. Impact of working environment on job satisfaction. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 23, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baah, K.; Amoako, G.K. Application of Frederick Herzberg’s two-factor theory in assessing and understanding employee motivation at work: A Ghanaian perspective. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, K.; Salim, H.; Loke, S.P. The key components of job satisfaction in Malaysia water utility industry. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.T. Antecedents and consequences of job satisfaction in the hotel industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monusova, G.A. Job satisfaction: International comparisons. World Econ. Int. Relat. 2008, 12, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sedliacikova, M.; Strokova, Z.; Klementova, J.; Satanova, A.; Moresova, M. Impacts of behavioral aspects on financial decision-making of owners of woodworking and furniture manufacturing and trading enterprises. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2020, 62, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jašková, D. Assessment of social developments in Slovakia in the context of human resources. Cent. Eur. J. Labour Law Pers. Manag. 2019, 2, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almobaireek, W.N.; Manolova, T.S. Entrepreneurial motivations among female university youth in Saudi Arabia. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2013, 14, S56–S75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inceoglu, I.; Segers, J.; Bartram, D. Age-related differences in work motivation. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2012, 85, 300–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnania-Kepuladze, T. Gender stereotypes and gender feature of job motivation: Differences or similarity? Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2010, 8, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, M. What men and women value at work: Implications for workplace health. Gend. Med. 2004, 1, 106–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joniakova, Z.; Blstakova, J. Age management as contemporary challenge to human resources management in Slovak companies. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 34, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zemke, R.; Raines, C.; Filipczak, B. Generations at Work; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bailyn, L. SMR forum: Patterned chaos in human resource management. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1993, 34, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Buttner, E.H. Female entrepreneurs: How far have they come? Bus. Horiz. 1993, 36, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almobaireek, W.N.; Manolova, T.S. Who wants to be and entrepreneur? Entrepreneurial intentions among Saudi university students. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 6, 4029–4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratričová, J.; Kirchmayer, Z. Barriers to work motivation of generation Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 2, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Goić, S. Employees older than 50 on Croatian labour market—Need for a new approach. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Idrees, M.D.; Hafeez, M.; Kim, J.Y. Workers’ age and the impact of psychological factors on the perception of safety at construction sites. Sustainability 2017, 9, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freund, A.M. Age-differential motivational consequences of optimization versus compensation focus in younger and older adults. Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 240–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.F.; Jacobsen, C.B.; Andersen, L.B. Managing employee motivation: Exploring the connections between managers’ enforcement actions, employee perceptions, and employee intrinsic motivation. Int. Public Manag. J. 2017, 20, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngyuyen, M.L. The impact of employees motivation on organizational effectiveness; Vaasan Ammattikorkeaukoulu: Vassa, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer, R.; Chen, G.; Pritchard, R.D. Work Motivation: Forging New Perspectives and Directions in the Post-Millenium; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, L.B.; Pallesen, T. “Not just for the money?” How financial incentives affect the number of publications at Danish Research Institutions. Int. Public Manag. J. 2008, 11, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.D.; Mujtaba, B.G.; Ruijs, A. Stress, task, and relationship orientations of Dutch: Do age, gender, education, and government work experience make a difference? Public Organ. Rev. 2014, 14, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Kozubíková, L.; Potkány, M. Education and gender-based differences in employee motivation. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2018, 19, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hitka, M. Model Analýzy Motivácie Zamestnancov Výrobných Podnikov; Technická Univerzita vo Zvolene: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stacho, Z.; Stachova, K.; Papula, J.; Papulová, Z.; Kohnová, L. Effective communication in organisations increases their competitiveness. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2019, 19, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ližbetinová, L. Clusters of Czech Consumers with Focus on Domestic Brands. In Proceedings of the 29th International Business Information Management Association Conference Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020 From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Vienna, Austria, 3–4 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sedliacikova, M.; Strokova, Z.; Drabek, J.; Mala, D. Controlling implementation: What are the benefits and barries for employees of wood processing enterprises? Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2019, 61, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, L.; Gašparíková, V. Penetration of small and medium sized food companies on foreign markets. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2010, 58, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lizbetinova, L.; Lorincova, S.; Tikhomirova, A.; Caha, Z. Motivational Preferences among Czech and Russian Men at Managerial Positions. In Proceedings of the 31th International Business Information Management Association Conference, Education Excellence and Innovation Management through Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, Milan, Italy, 25–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Loucanova, E.; Olsiakova, M.; Dzian, M. Suitability of innovative marketing communication forms in the furniture industry. Acta Fac. Xylologiae Zvolen Publica Slovaca 2018, 60, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, O.; Kozak, M.A. Designing and effective organizational employee motivation system based on abcd model for hotel establishments. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 23, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faletar, J.; Jelačić, D.; Sedliačiková, M.; Jazbec, A.; Hajdúchová, I. Motivation employees in a wood processing company before and after restructuring. BioResources 2016, 11, 2504–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Carpenter, N.C. Employees’ motivation for personal initiative: The joint influence of status and communion striving. J. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 12, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Balazova, Z.; Grazulis, V.; Lejskova, P. Differences in employee motivation in selected countries of CEE (Slovakia, Lithuania and the Czech Republic). Inz. Ekon. 2018, 5, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Lorincova, S.; Bartakova, G.P.; Lizbetinova, L.; Starchon, P.; Li, C.; Zaborova, E.; Markova, T.; Schmidtova, J. Strategic tool of human resource management for operation of SMEs in the wood-processing industry. BioResources 2018, 13, 2759–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitka, M.; Lorincová, S.; Ližbetinová, L.; Schmidtová, J. Motivation preferences of Hungarian and Slovak employees are significantly different. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2016, 25, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lizbetinova, L.; Hitka, M.; Zaborova, E.; Weberova, D. Motivational Preferences of the Czech and Russian Blue-Collar Workers. In Proceedings of the Conference of Innovation Management and Education Excellence Through Vision 2020, Milan, Italy, 25–26 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Gender | Male | Female | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <30 | <40 | <50 | 50+ | <30 | <40 | <50 | 50+ | ||

| Job category | Manager | 309 | 593 | 620 | 362 | 371 | 578 | 548 | 326 | 3707 |

| BCW | 3187 | 3522 | 2997 | 1641 | 1811 | 2132 | 2089 | 1185 | 18,564 | |

| WCW | 1125 | 1523 | 1132 | 699 | 1574 | 2402 | 2342 | 1547 | 12,344 | |

| Total | 4621 | 5638 | 4749 | 2702 | 3756 | 5112 | 4979 | 3058 | 34,615 | |

| No. | Motivation factor | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Basic salary | 4.509 |

| 2. | Good work team | 4.427 |

| 3. | Atmosphere in the workplace | 4.416 |

| 4. | Fair appraisal system | 4.410 |

| 5. | Job security | 4.398 |

| 6. | Supervisor’s approach | 4.370 |

| 7. | Fringe benefits | 4.344 |

| 8. | Communication in the workplace | 4.256 |

| 9. | Working hours | 4.199 |

| 10. | Work environment | 4.180 |

| Gender | Age | Job Category | Total | Mean | Standard Deviation | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −95.00% | −95.00% | ||||||

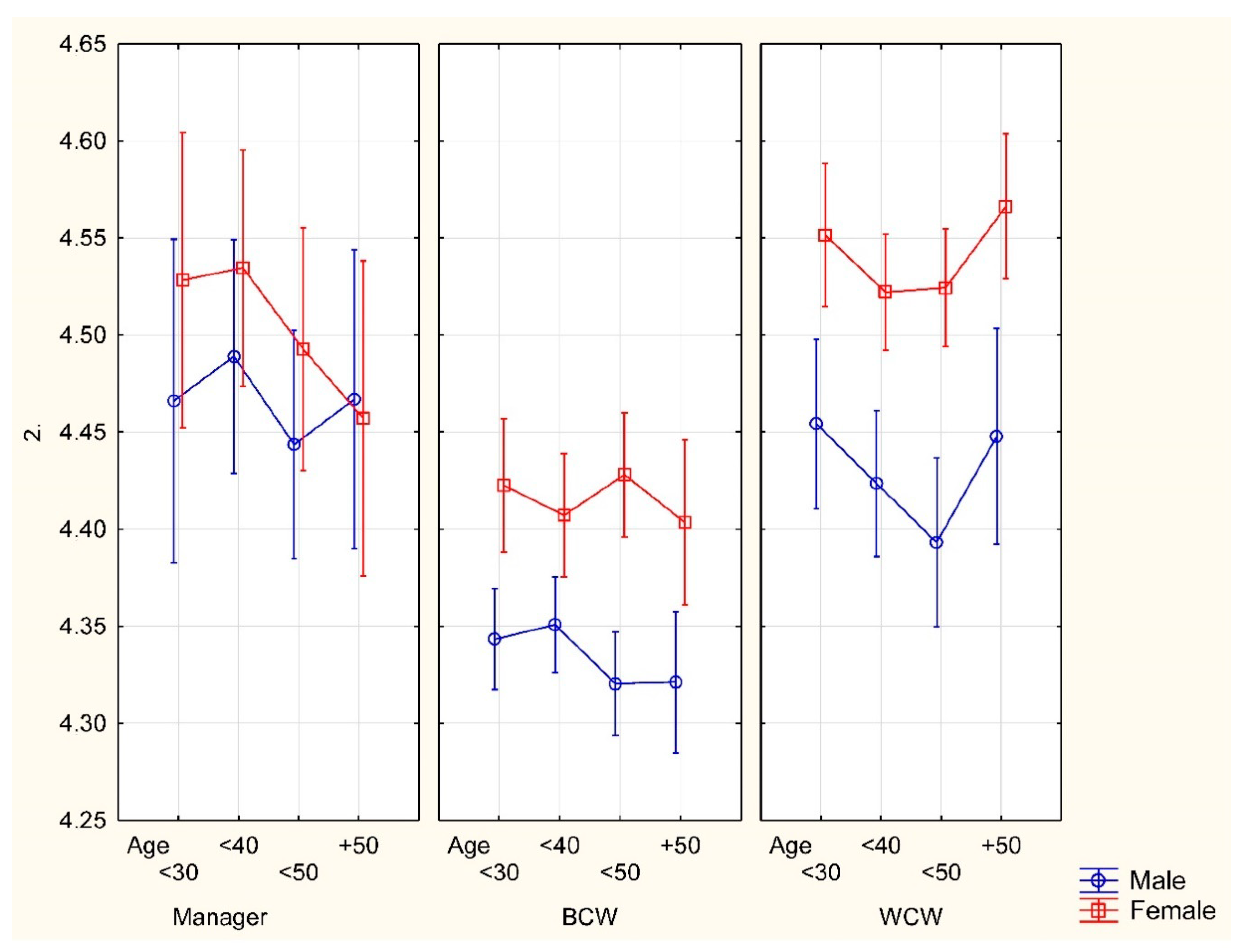

| Male | <30 | manager | 309 | 4.46601942 | 0.827477005 | 4.37339304 | 4.5586458 |

| BCW | 3187 | 4.34326953 | 0.837459302 | 4.31418341 | 4.37235565 | ||

| WCW | 1125 | 4.45422222 | 0.729946888 | 4.41152192 | 4.49692253 | ||

| <40 | manager | 593 | 4.48903879 | 0.739999489 | 4.42935712 | 4.54872046 | |

| BCW | 3522 | 4.35065304 | 0.790806213 | 4.32452705 | 4.37677903 | ||

| WCW | 1523 | 4.42350624 | 0.698147764 | 4.38841562 | 4.45859685 | ||

| <50 | manager | 620 | 4.44354839 | 0.806900964 | 4.37990951 | 4.50718726 | |

| BCW | 2997 | 4.32032032 | 0.792254833 | 4.29194472 | 4.34869592 | ||

| WCW | 1132 | 4.39310954 | 0.747566789 | 4.34951422 | 4.43670486 | ||

| 50+ | manager | 362 | 4.46685083 | 0.694462087 | 4.39507127 | 4.53863039 | |

| BCW | 1641 | 4.32114564 | 0.800821319 | 4.2823708 | 4.35992049 | ||

| WCW | 699 | 4.44778255 | 0.706948792 | 4.39528353 | 4.50028156 | ||

| Female | <30 | manager | 371 | 4.52830189 | 0.713674977 | 4.45544266 | 4.60116111 |

| BCW | 1811 | 4.42241855 | 0.790778974 | 4.38597384 | 4.45886326 | ||

| WCW | 1574 | 4.55146125 | 0.64249377 | 4.51969624 | 4.58322625 | ||

| <40 | manager | 578 | 4.53460208 | 0.686346112 | 4.47853095 | 4.5906732 | |

| BCW | 2132 | 4.40712946 | 0.766684168 | 4.37456696 | 4.43969195 | ||

| WCW | 2402 | 4.52206495 | 0.673571593 | 4.4951146 | 4.54901529 | ||

| <50 | manager | 548 | 4.49270073 | 0.719245495 | 4.43234799 | 4.55305347 | |

| BCW | 2089 | 4.42795596 | 0.736762935 | 4.39634349 | 4.45956843 | ||

| WCW | 2342 | 4.52433817 | 0.672303329 | 4.49709583 | 4.55158052 | ||

| 50+ | manager | 326 | 4.45705521 | 0.770412024 | 4.37311257 | 4.54099786 | |

| BCW | 1185 | 4.40337553 | 0.778287761 | 4.35901739 | 4.44773366 | ||

| WCW | 1547 | 4.56625727 | 0.60182916 | 4.5362438 | 4.59627075 | ||

| Effect | Degree of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Average Square | F-Test | p-Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute term | 1 | 400,110.5 | 400,110.5 | 715,981.7 | 0.000000 |

| Gender | 1 | 29.6 | 29.6 | 53.0 | 0.000000 |

| Age | 3 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.229204 |

| Job category | 2 | 93.2 | 46.6 | 83.4 | 0.000000 |

| Gender versus age | 3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.641831 |

| Gender versus job category | 2 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 3.5 | 0.030951 |

| Age versus job category | 6 | 4.5 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.235433 |

| Gender versus age versus job category | 6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.945991 |

| Error | 34,591 | 19,330.4 | |||

| Total | 34,614 | 19,544.7 |

| Gender | Age | Job Category | Total | Mean | Standard Deviation | Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −95.00% | −95.00% | ||||||

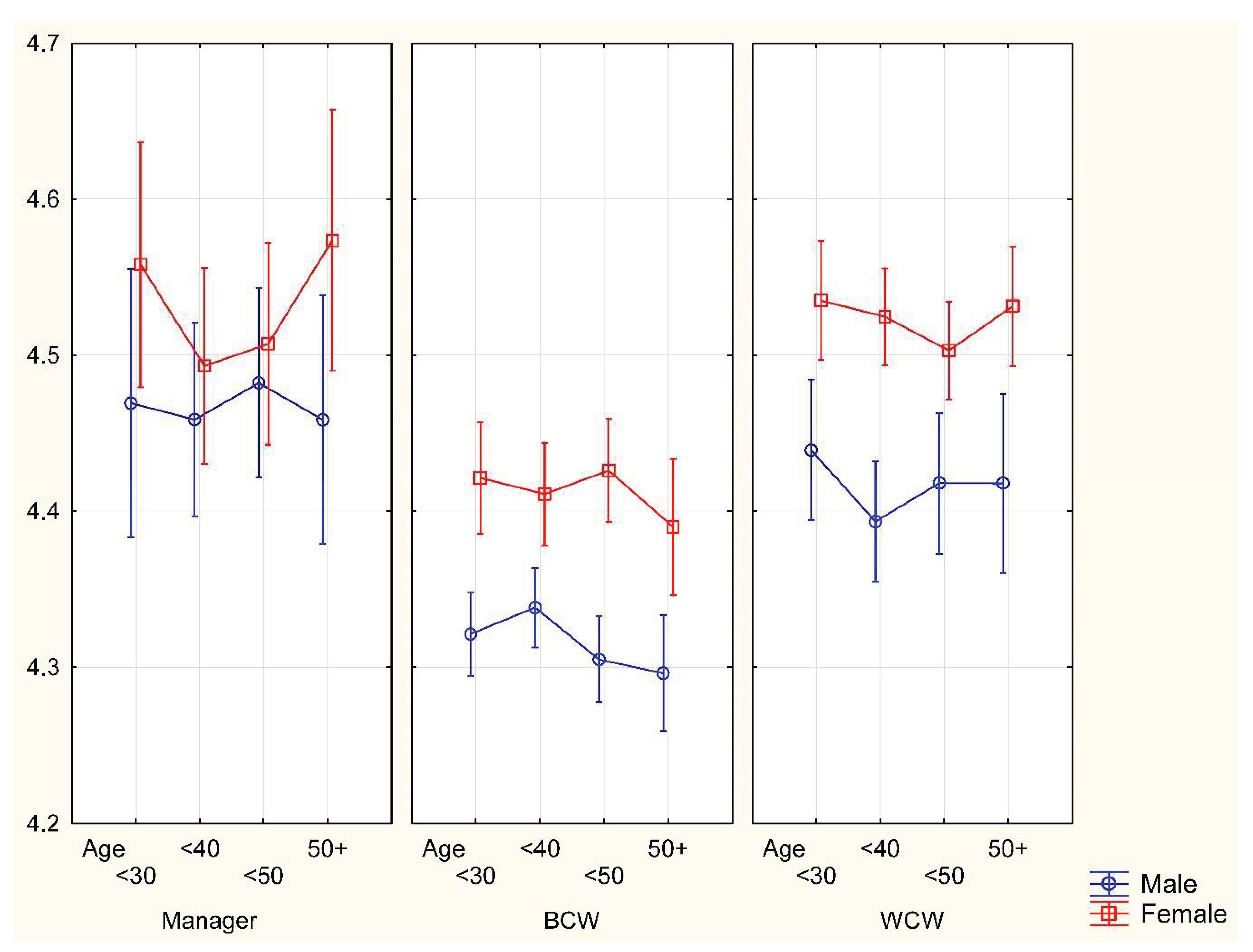

| Male | <30 | manager | 309 | 4.469256 | 0.807750 | 4.378837 | 4.559674 |

| BCW | 3187 | 4.321305 | 0.874588 | 4.290930 | 4.351681 | ||

| WCW | 1125 | 4.439111 | 0.780705 | 4.393442 | 4.484781 | ||

| <40 | manager | 593 | 4.458685 | 0.748013 | 4.398357 | 4.519013 | |

| BCW | 3522 | 4.338160 | 0.805803 | 4.311539 | 4.364782 | ||

| WCW | 1523 | 4.393303 | 0.758401 | 4.355184 | 4.431422 | ||

| <50 | manager | 620 | 4.482258 | 0.767688 | 4.421712 | 4.542804 | |

| BCW | 2997 | 4.304972 | 0.810326 | 4.275949 | 4.333994 | ||

| WCW | 1132 | 4.417845 | 0.730393 | 4.375251 | 4.460438 | ||

| 50+ | manager | 362 | 4.458564 | 0.791013 | 4.376804 | 4.540323 | |

| BCW | 1641 | 4.296161 | 0.816770 | 4.256614 | 4.335708 | ||

| WCW | 699 | 4.417740 | 0.712174 | 4.364853 | 4.470627 | ||

| Female | <30 | manager | 371 | 4.557951 | 0.700394 | 4.486448 | 4.629455 |

| BCW | 1811 | 4.421314 | 0.800393 | 4.384426 | 4.458202 | ||

| WCW | 1574 | 4.534943 | 0.677294 | 4.501457 | 4.568428 | ||

| <40 | manager | 578 | 4.493080 | 0.752203 | 4.431628 | 4.554531 | |

| BCW | 2132 | 4.410882 | 0.795361 | 4.377101 | 4.444662 | ||

| WCW | 2402 | 4.524563 | 0.673485 | 4.497616 | 4.551510 | ||

| <50 | manager | 548 | 4.507299 | 0.709006 | 4.447806 | 4.566793 | |

| BCW | 2089 | 4.426041 | 0.782600 | 4.392462 | 4.459620 | ||

| WCW | 2342 | 4.502989 | 0.701947 | 4.474545 | 4.531432 | ||

| 50+ | manager | 326 | 4.573620 | 0.687768 | 4.498682 | 4.648558 | |

| BCW | 1185 | 4.389873 | 0.843235 | 4.341814 | 4.437933 | ||

| WCW | 1547 | 4.531351 | 0.641004 | 4.499384 | 4.563318 | ||

| Effect | Degree of Freedom | Sum of Squares | Average Square | F-Test | p-Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute term | 1 | 399,467.2 | 399,467.2 | 671,113.0 | 0.000000 |

| Gender | 1 | 40.7 | 40.7 | 68.4 | 0.000000 |

| Age | 3 | 1.2 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.555673 |

| Job category | 2 | 101.0 | 50.5 | 84.9 | 0.000000 |

| Gender versus age | 3 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.748412 |

| Gender versus job category | 2 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.405118 |

| Age versus job category | 6 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.506409 |

| Gender versus age versus job category | 6 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.432415 |

| Error | 34,591 | 20,589.6 | |||

| Total | 34,614 | 20,820.4 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lorincová, S.; Čambál, M.; Miklošík, A.; Balážová, Ž.; Gyurák Babeľová, Z.; Hitka, M. Sustainability in Business Process Management as an Important Strategic Challenge in Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155941

Lorincová S, Čambál M, Miklošík A, Balážová Ž, Gyurák Babeľová Z, Hitka M. Sustainability in Business Process Management as an Important Strategic Challenge in Human Resource Management. Sustainability. 2020; 12(15):5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155941

Chicago/Turabian StyleLorincová, Silvia, Miloš Čambál, Andrej Miklošík, Žaneta Balážová, Zdenka Gyurák Babeľová, and Miloš Hitka. 2020. "Sustainability in Business Process Management as an Important Strategic Challenge in Human Resource Management" Sustainability 12, no. 15: 5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155941

APA StyleLorincová, S., Čambál, M., Miklošík, A., Balážová, Ž., Gyurák Babeľová, Z., & Hitka, M. (2020). Sustainability in Business Process Management as an Important Strategic Challenge in Human Resource Management. Sustainability, 12(15), 5941. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155941