Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

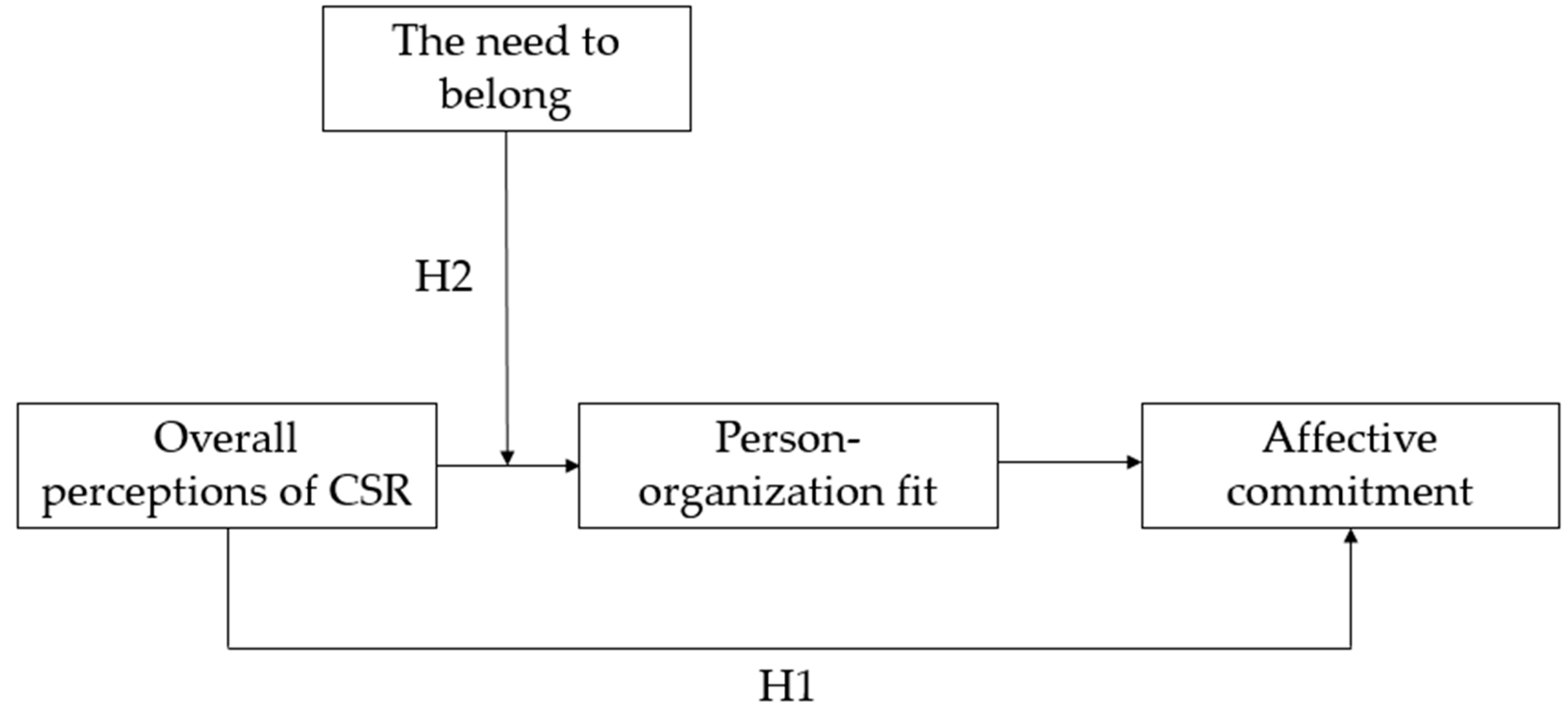

2.1. PO Fit as a Mediator of the Employees’ Perception of CSR and Organizational Commitment Relationship

2.2. The Moderating Role of the Need to Belong

3. Method and Results

3.1. Study 1

3.1.1. Sample and Procedure

3.1.2. Measures

3.1.3. Statistical Analyses

3.1.4. Results

- Perception of CSR has a positive effect on PO fit (b = 0.61, SE = 0.05).

- PO fit has a positive effect on affective commitment (b = 0.23, SE = 0.08).

- The indirect effect of overall CSR is 0.14 (p < 0.01; CI 95% [0.05 0.24]).

3.2. Study 2

3.2.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2.2. Measures

3.2.3. Statistical Analyses

3.2.4. Results

- Perception of CSR has a positive effect on PO fit (b = 0.68, SD = 0.06).

- PO fit has a positive effect on affective engagement (b = 0.50, SD = 0.09).

- The indirect effect of overall perception of CSR on affective commitment is 0.34 (SD = 0.07; CI 95% [0.34; 0.48]).

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limits and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee Min-Dong, P. A review of the theories of corporate social responsibility: Its evolutionary path and the road ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Frynas, G.; Stephens, S. Political corporate social responsibility: Reviewing theories and setting new agendas. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 483–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Marique, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Swaen, V. Understanding employees’ responses to corporate social responsibility: Mediating roles of overall justice and organizational identification. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A. Corporate social responsibility and organizational psychology: An integrative review. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Willness, C.; Glavas, A. When corporate social responsibility (CSR) meets organizational psychology: New frontiers in micro-CSR research, and fulfilling a quid pro quo through multilevel insights. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockerts, K.; Moir, L. Communicating corporate responsibility to investors: The changing role of the investor relations function. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 52, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaen, V.; Chumpitaz, R. Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2008, 23, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.M.; Park, S.Y.; Rapert, M.; Newman, C. Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1558–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Stone, B.; Heiner, K. Exploring the relationship between corporate social performance and employer attractiveness. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 292–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, D.; Turban, D. Corporate social performance as a competitive advantage in attracting a quality workforce. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.; Shao, R.; Thornton, M.; Skarlicki, D. Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Pers. Psychol. 2013, 66, 895–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.; Dunford, B.; Boss, A.; Boss, W.; Angermeier, I. Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Gilat, G.; Waldman, D. The role of perceived organizational performance in organizational identification, adjustment and job performance. J. Manag. Stud. 2007, 44, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Piderit, S.K. How does doing good matter? Effects of corporate citizenship on employees. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2009, 36, 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, D. The relationship between perceptions of corporate citizenship and organizational commitment. Bus. Soc. 2004, 43, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. How corporate social responsibility influences organizational commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A.; Rayton, B. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2007, 18, 1701–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, K.; Hattrup, K.; Spiess, S.O.; Lin-Hi, N. The effects of corporate social responsibility on employees’ affective commitment: A cross-cultural investigation. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 97, 1186–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Jiuhua Zhu, C. Effects of socially responsible human resource management on employee organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 22, 3020–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.; Herscovitch, L. Commitment in the workplace: Toward a general model. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2001, 11, 299–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Paunonen, S.V.; Gellatly, I.R.; Jackson, D.N. Organizational commitment and job performance: It’s the nature of commitment that counts. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism program. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 857–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugré, C. Managing Fairness in Organizations; Quorum Books: Westport, CT, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.; Shabana, K. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D. Corporate social performance revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.; Smith, N. Relationships: The real challenge of corporate global citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2000, 105, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Ganapathi, J.; Aguilera, R.V.; Williams, C.A. Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. J. Organ. Behav. 2006, 27, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Akremi, A.; Gond, J.P.; Swaen, V.; De Roeck, K.; Igalens, J. How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. J. Manag. 2015, 44, 619–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S.; Judge, T. Organizational Behavior; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, Essex, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, M.; Mayer, D.M.; Tost, L.P.; Wellman, N. When corporate social responsibility motivates employee citizenship behavior: The sensitizing role of task significance. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2018, 144, 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D. An employee-centered model of organizational justice and social responsibility. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 1, 72–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gond, J.P.; El Akremi, A.; Swaen, V.; Nishat, B. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, C.; Skitka, L. Corporate social responsibility as a source of employee satisfaction. Res. Organ. Behav. 2012, 32, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.P.; Lyau, N.M.; Tsai, Y.H.; Chen, W.Y.; Chiu, C.K. Modeling corporate citizenship and its relationship with organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachos, P.; Panagopoulos, N.; Rapp, A. Employee judgments of and behaviors toward corporate social responsibility: A multi study investigation of direct, cascading, and moderating effects. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 990–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.; Esteban, R. Corporate social responsibility and employee commitment. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.S.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.; Porter, L.; Steers, R. Employee-organization linkage. In The Psychology of Commitment Absenteeism and Turnover; Academic Press: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, J.; Allen, N. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.; Meyer, J. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. J. Vocat. Behav. 1996, 49, 252–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. Commitment in the Workplace: Theory, Research, and Application; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Riketta, M. Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2002, 23, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. Organizational socialization tactics: A longitudinal analysis of links to newcomers’ commitment and role orientation. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 847–858. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, O.; Payaud, M.; Merunka, D.; Valette-Florence, P. The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C.; Hult, G.T.M. Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, A.; Ribeiro, N.; Cunha, M.P. Perceptions of organizational virtuousness and happiness as predictors of organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stites, J.P.; Michael, J.H. Organizational commitment in manufacturing employees: Relationships with corporate social performance. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.T.; Kim, N.M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R. Fairness as moral virtue. In Managerial Ethics; Schminke, M., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1998; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Folger, R. Fairness as deonance. In Theoretical and Cultural Perspectives on Organizational Justice; Gilliland, S., Steiner, D., Skarlicki, D., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Greenwich, CT, USA, 2001; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Beugre, C.D. Development and validation of a deontic justice scale. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2163–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Greenberg, J. Doing justice to organizational justice. In Theoretical and Cultural Perspectives on Organizational Justice; Erlbaum Associates: Mahwa, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 217–242. [Google Scholar]

- Cropanzano, R.; Byrne, Z.S.; Bobocel, D.R.; Rupp, D.E. Moral virtues, fairness heuristics, social entities, and other denizens of organizational justice. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 164–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouraoui, K.; Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M.; Russo, M. Corporate social responsibility and employees’ affective commitment: A multiple mediation model. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.J.; Woehr, D.J. A quantitative review of the relationship between person-organization fit and behavioral outcomes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcshane, L.; Cunningham, P. To thine own self be true? Employees’ judgments of the authenticity of their organization’s corporate social responsibility program. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, J.W.; Cyr, L.A. An integrative analysis of person-organization fit theories. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2004, 12, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 459–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly III, C.A.; Chatman, J.; Caldwell, D.F. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 487–516. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Meglino, B.M.; Ravlin, E.C.; Adkins, C.L. The measurement of work value congruence: A field study comparison. J. Manag. 1992, 18, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatman, J.A. Improving interactional organizational research: A model of person-organization fit. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 333–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meglino, B.M.; Ravlin, E.C.; Adkins, C.L. A work values approach to corporate culture: A field test of the value congruence process and its relationship to individual outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 1989, 74, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Interviewers’ perceptions of person-organization fit and organizational selection decisions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 546–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westerman, J.W.; Vanka, S. A cross-cultural empirical analysis of person-organization fit measures as predictors of student performance in business education: Comparing students in the United States and India. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2005, 4, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folger, R.; Cropanzano, R. Fairness theory: Justice as accountability. Adv. Organ. Justice 2001, 1, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R.; Kelly, K.M.; Cottrell, C.A.; Schreindorfer, L.S. Construct validity of the need to belong scale: Mapping the nomological network. J. Personal. Assess. 2013, 95, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, J.; Park, B. A model of the ingroup as a social resource. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 9, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.; Tice, D. Anxiety and social exclusion. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1990, 9, 165–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthes, J.; Hayes, A.F.; Rojas, H.; Shen, F.; Min, S.J.; Dylko, I.B. Exemplifying a dispositional approach to cross-cultural spiral of silence research: Fear of social isolation and the inclination to self-censor. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2012, 24, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Sommer, K. Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1997, 23, 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, S.; Derfler-Rozin, R.; Pitesa, M.; Mitchell, M.S.; Pillutla, M.M. Unethical for the sake of the group: Risk of social exclusion and pro-group unethical behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitman, R. The Architect of Genocide: Himmler and the Final Solution; Brandeis University Press: Hanover, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Lathlean, J. ‘Don’t rock the boat’: Nursing students’ experiences of conformity and compliance. Nurse Educ. Today 2009, 29, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, K.R.; Wheeler, S.C.; Smeesters, D. Significant other primes and behavior: Motivation to respond to social cues moderates pursuit of prime-induced goals. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 33, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R. Belonging motivation. In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior; Leary, M.R., Hoyle, R.H., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 400–409. [Google Scholar]

- Rios, K.; Chen, Z. Experimental evidence for minorities’ hesitancy in reporting their opinions: The roles of optimal distinctiveness needs and normative influence. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvallo, M.; Pelham, B.W. When fiends become friends: The need to belong and perceptions of personal and group discrimination. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 90, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.R. Affiliation, acceptance, and belonging: The pursuit of interpersonal connection. In Handbook of Social Psychology; Fiske, S.T., Gilbert, D.T., Lindzay, G., Eds.; Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 864–898. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Swencionis, J.K.; O’Connor, R.C.; Cunningham, W.A. Motivated social memory: Belonging needs moderate the own-group bias in face recognition. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cremer, D.; Blader, S.L. Why do people care about procedural fairness? The importance of belongingness in responding and attending to procedures. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-cultural research methods. In Environment and Culture; Altman, I., Rapoport, A., Wohlwill, J.F., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; pp. 47–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; Judge, T.A. Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1996, 67, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3. In Boenningstedt: SmartPLS GmbH; University of Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: New York NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.; Mallory, D. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J. People and Profits? The Search for a Link between a Company’s Social and Financial Performance; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine, S.; Fleischman, G. Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 77, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of relations between person-organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Number of Participants | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 80 | 44.19 |

| Female | 101 | 55.81 |

| Age | ||

| <26 years | 5 | 3.10 |

| 26–35 | 70 | 43.47 |

| 36–45 | 59 | 36.64 |

| 46–55 | 24 | 14.90 |

| 56+ | 3 | 1.86 |

| Level of education | ||

| Middle school | 1 | 0.55 |

| High school | 0 | 0 |

| University (2 years) | 0 | 0 |

| University (3 or 4 years) | 6 | 3.33 |

| University (5 years or more) | 173 | 96.11 |

| Tenure | ||

| Less than 1 year | 12 | 6.66 |

| between 1 and 3 years | 37 | 20.55 |

| between 3 and 10 years | 87 | 48.33 |

| More than 10 years | 44 | 24.44 |

| Variables | Cronbach (α) | Mean | CR | Variance | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CSR | 0.946 | 3.33 | 0.95 | 1.26 | 1 | |

| (2) Affective commitment | 0.862 | 4.96 | 0.89 | 1.30 | 0.536 ** | 1 |

| (3) Person-organization fit | 0.937 | 3.70 | 0.96 | 1.59 | 0.606 ** | 0.443 ** |

| Effect | b | SD | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of overall perception of CSR on PO fit | 0.61 ** | 0.05 | [0.6162 0.9118] |

| Effect of PO fit on affective commitment | 0.23 ** | 0.08 | [0.0265 0.2809] |

| Effect of perception of CSR on affective commitment | 0.40 ** | 0.07 | [0.2786 0.5992] |

| Variables | Cronbach (α) | CR | Mean | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) CSR | 0.92 | 0.93 | 4.87 | 0.95 | 1 | ||

| (2) Affective commitment | 0.87 | 0.90 | 4.35 | 1.34 | 0.61 ** | 1 | |

| (3) Person-organization fit | 0.89 | 0.91 | 4.26 | 1.25 | 0.71 ** | 0.67 ** | 1 |

| (4) The need to belong | 0.77 | 0.79 | 4.11 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Effect | b | SD | CI 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of overall perception of CSR on PO fit | 0.68 ** | 0.06 | [0.54; 0.75] |

| Effect of PO fit it on affective commitment | 0.50 ** | 0.09 | [0.32; 0.69] |

| Effect of overall perception of CSR on affective commitment | 0.27 ** | 0.06 | [0.07; 0.46] |

| Effect of need to belong on PO fit | 0.05 | 0.03 | [−0.1; 0.15] |

| Effect of the interaction of perception of CSR and need to belong on PO fit | −0.15 * | 0.06 | [−0.29; −0.07] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouraoui, K.; Bensemmane, S.; Ohana, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145833

Bouraoui K, Bensemmane S, Ohana M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Study. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145833

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouraoui, Khadija, Sonia Bensemmane, and Marc Ohana. 2020. "Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Study" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145833

APA StyleBouraoui, K., Bensemmane, S., & Ohana, M. (2020). Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Affective Commitment: A Moderated Mediation Study. Sustainability, 12(14), 5833. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145833