“That is Not What I Live For”: How Lower-Level Green Employees Cope with Identity Tensions at Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Green Identity Work

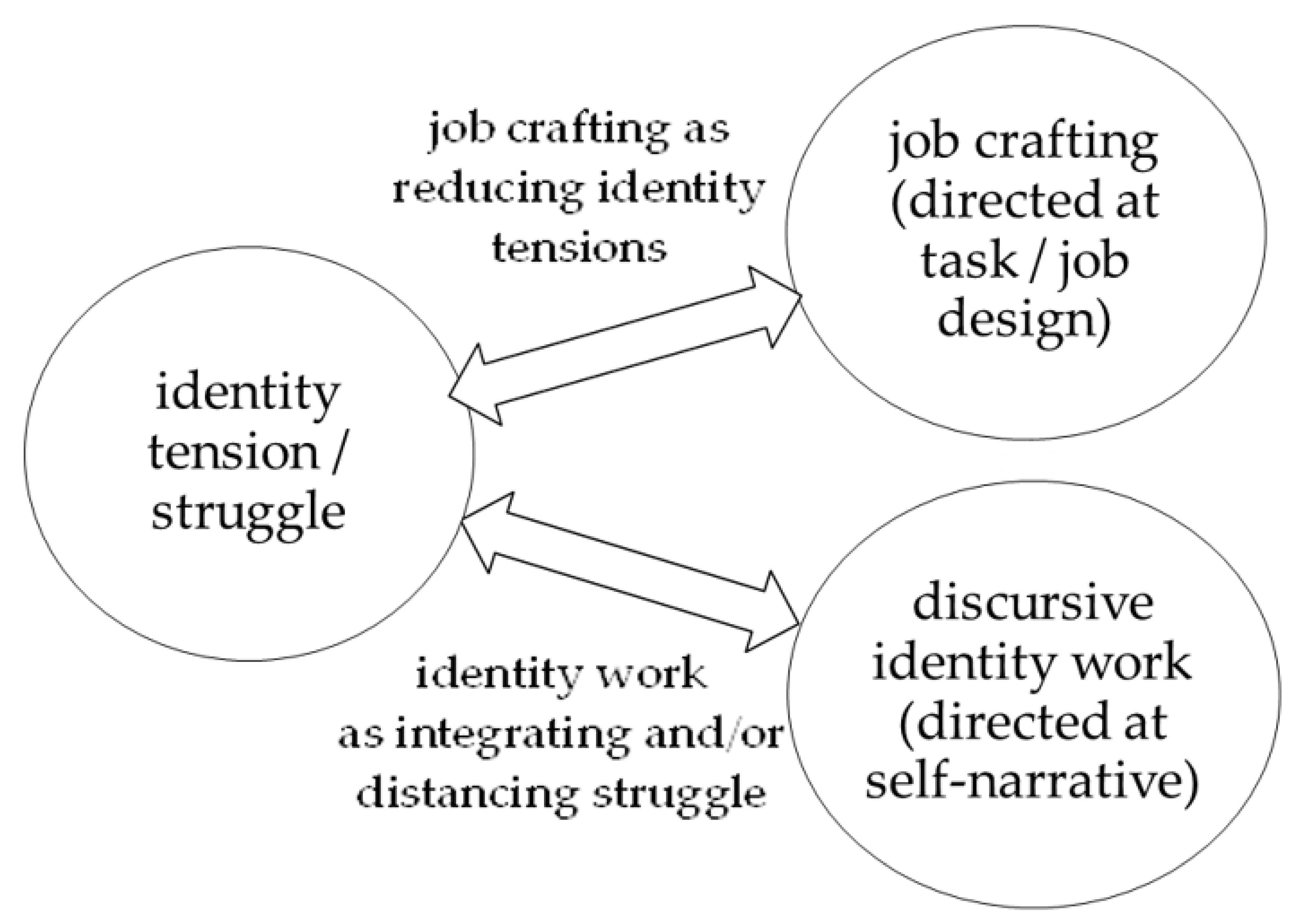

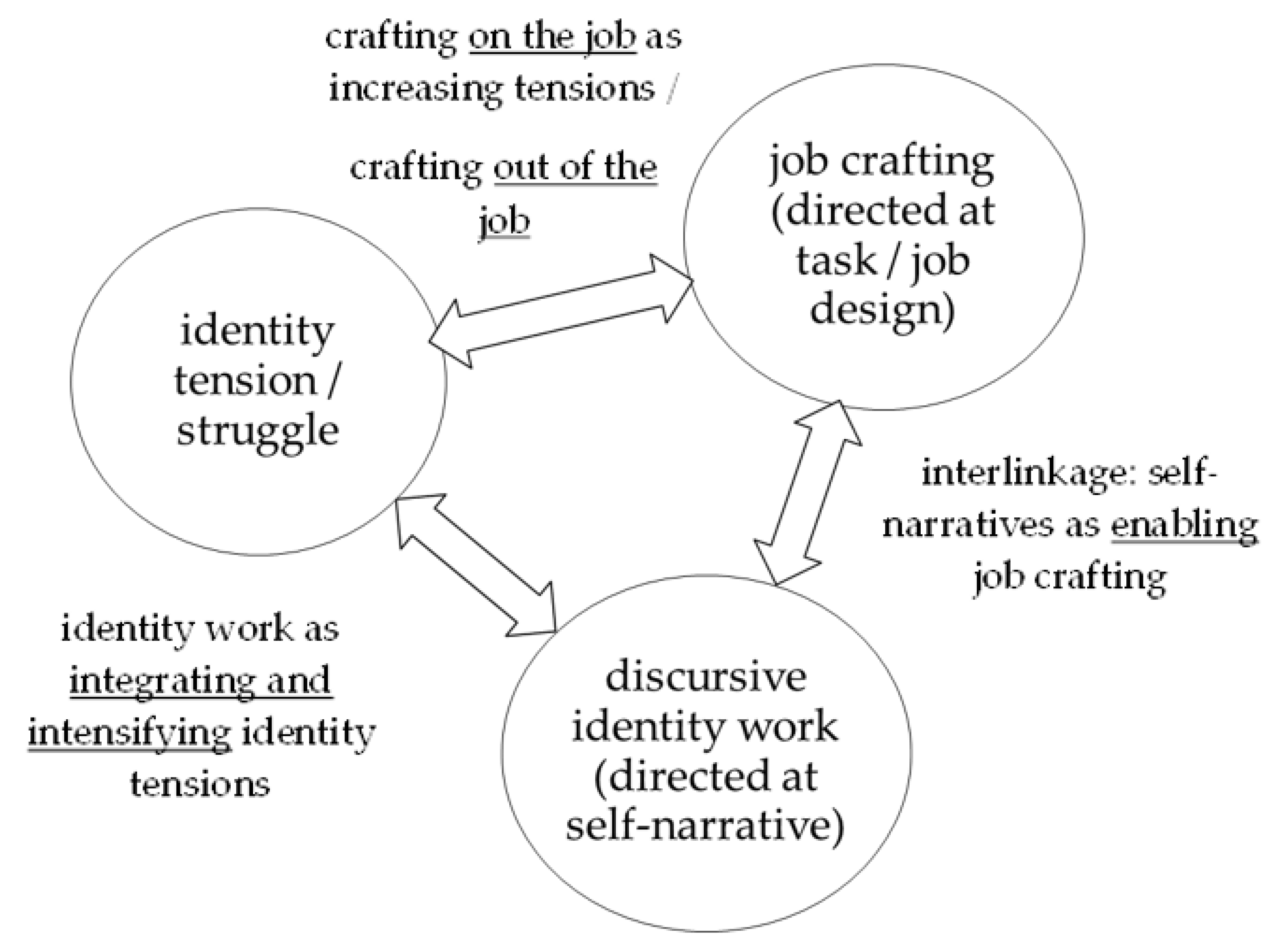

2.2. Job Crafting as Identity Work

2.3. Resources Facilitating Identity Work and Job Crafting

3. Studying Green Employees’ Identity Work: Methodology

4. Findings: Green Identities at Work

4.1. Perceived Misalignment: “That Is Not What I Live For”

“When I am engaged [for my green projects] now, and spend time to get access to different fields, that wouldn’t get me anywhere, except that I get a roasting, because I don’t fulfill my working objectives.”(Sara)

“Our main customers are food processing companies, mainly meat and fish processing. (…) And that naturally does not go well with my way of thinking. And part of that is disgusting. And so I ask myself sometimes if I am in the right place. (…) Because that goes against the grain. Because that is not what I live for.”(Susan)

4.2. Identity Work Strategies

4.2.1. Exposing

4.2.2. Enduring

“And I think other colleagues are shaking their heads and think: What is going on with her? […]. With one colleague I had a heated discussion about coffee capsules. They are a red rag to me […]. I find it absolutely an incredible environmental sin […]. Well, that [discussion] stayed unsolved: He continues to buy coffee capsules and I continue to buy my fair-trade coffee.”(Sara)

“I have always written [it] into the briefings for our top management […] What do you do with the old [mobile phone] devices? These questions are asked again. And I have asked again, again, and again, like a mantra. Rolled it out, again and again. And I believe you can change something with that after all. It is truly grueling, but it does work, I believe, quite well.”(Sean)

4.2.3. Dodging

“And, so there are really only very few electricity suppliers that [offer] sustainable green energy. […] And then I thought, well now, come on?! […] It will be done now. And I also won’t talk about it. I’m just doing it. I can sign the contracts and no one really knows actually. I will just do it.”

4.2.4. Dissolving

“Well, I mean: One is in a conflict. On the one hand, there is something to it, when you earn your living, I’d say, in a job that you don’t put so much of yourself into. Yes, but then in your free time […], you can unfold your own activities, where you have a certain degree of control.”(Lucy)

4.3. Resources Enabling Green Identity Work Strategies

4.3.1. Constructing the Organization as a Lever for Change

“Well […] some say then: You work for [company X]? Yes? And sustainability? Mhm! Then I always say: Yes, sure, that’s exactly where you can move something. I don’t have to be in a citizens’ movement, (…) I have to sit in the headquarters.”(Megan)

4.3.2. Perceiving Oneself as a “Lone Fighter”

“And in the end, you somehow have to reflect on it, and then—some people might think: That is arrogant—but you have to have, somehow, enough self-esteem to say to yourself: ‘No, the way I am is completely alright.’ And you don’t have to conform. And why should I conform? (…) I don’t accept that I have to change my personality just to seem well adjusted (…). I just don’t want to become like my colleagues.”(Nell)

4.3.3. Building Supportive Networks

“[…] before there was this connection to Kate and Lisa, I had been thinking intermittently: ‘No, no, after the probation period, I’ll be gone.’ […] Because: You get crazy. When you have such a position of a lone fighter, and you don’t know, somehow, ‘Whom can I tell what’, and there is no exchange, and you feel somehow completely lost, right?”(Megan)

5. Discussion

5.1. Contribution

5.2. Limitations and Directions for Further Research

5.3. Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Name * | Employee Position at Time of Interview, Industry/Sector | Green Activism in Private/Public Sphere | Green Initiatives at Work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carolin | Sales and marketing employee, manufacturing industry | Ecological lifestyle | Initiated change of packaging material |

| Cedric | Team leader, banking industry | Ecological lifestyle, apiculturist | Initiated the installation of a small wind turbine on the company’s premises, initiated sustainability reporting; established a beehive on corporate premises |

| Elizabeth | Production worker, manufacturing industry | Ecological lifestyle | Resisted and revised ecologically harmful practices at work |

| Keith | Business economist, power and energy industry | Greenpeace activist | Established that corporate solar parks obtain the required energy from a green electricity supplier; launched initiatives to improve the energy consumption of the transport fleet; implemented a company-specific local transport pass |

| Lucy | Sociologist, public sector | Initiated solar energy networks and cooperatives; ecological lifestyle | Lobbies for renewable energy and energy efficiency |

| Megan | Team leader, extractive industry | Ecological lifestyle, gave up her car; engages in NGOs against racism/concerning global migration | Developed and promoted several green ideas; engages substantially in the organizational transformation towards sustainability, e.g., by provoking an internal discussion of corporate sustainability risks |

| Nell | Team leader, extractive industry | Ecological lifestyle | Submitted a proposal to use more electric vehicles in the vehicle fleet of the company; initiated a competition to promote cycling to work; established an informal circle on environmental issues with colleagues |

| Jerry | Product manager, chemical manufacturing industry | Climate change activist; engages in ecological gardening | Engaged in discussion for renewable energy in the workplace |

| Patrick | Clerk sales and distribution, power and energy industry [founded a green energy start-up after the period of interviewing] | Longtime anti-nuclear activist | Engaged in aligning the conventional business model to the German energy transition |

| Rachel | Geographer, geographic services | Active in an ecological association, lives in ‘green’ co-housing project | Lobbied for usage of trains rather than flights for business travel; initiated switch to fair-trade coffee; reduces her working time for private green engagement |

| Rebecca | Clerk, financial industry | Active in an NGO for Africa; ecological lifestyle | Collected garbage at work to recycle at home; initiated paper-less office |

| Richard | Project manager, engineering industry | Ecological lifestyle, fair-trade activist | Sold fair-trade chocolate at work and donates proceeds to street children; tried to achieve that official supplier switches to fair-trade coffee and chocolate; openly rejected a management position on corporate nuclear projects; rides a bicycle (with an anti-nuclear-power sticker) to work |

| Sandra | Corporate development clerk, insurance industry | Ecological lifestyle | Engaged colleagues in discussion about meat/veganism |

| Sara | Employee process management and IT, chemical industry [applied for a job in the sustainability department] | Animal protection activist; engaged in pedagogical projects for eco-foresting | Requested to the CSR department to compensate the CO2 emissions of her flights; launched discussions about genetic engineering, animal testing, and future sustainability strategies in her company; applied for a job in the sustainability department |

| Scott | Technical service team leader, telecommunication industry [left the company after the period of interviewing to start an e-bike shop] | Chairman of a local lobbyist group for bicyclists; helps out in an eco-café and e-bike shop | Tried to established an employee cooperative for renewable energy; initiative for ecological modernization of the company’s car pool (natural gas cars, electric vehicles); established photovoltaic systems on the roof of company buildings in shared ownership with nine colleagues |

| Sean | Clerk, transformation management, telecommunication industry | Leads a sustainability group in political foundation for talented students | Tried to implement a business concept to reduce electronic waste and to extend the durability of electronic products |

| Susan | Accountant, manufacturing industry | Greenpeace activist | Initiated the change to a green energy supplier at her company without corporate approval; frequently challenges resource-wasteful behavior; sought to establish a photovoltaic system on company premises; initiated usage of recycled paper and ecological detergents; compensates her CO2 emissions of each business flight against corporate policy |

| Taylor | Clerk, forest management, public sector | Founded and leads several cooperatives and associations for renewable energy | Initiated an energy-saving program among colleagues |

| Thomas | Clerk, retail industry | Leads a local ecological group | Developed and launched a game for saving energy at work |

| William | Controller, automotive industry [self-employed advisor on renewable energy after the interview period] | Leads a national association for renewable energies; has founded renewable energy cooperatives | Tried to initiate the establishment of a photovoltaic system on the company premises |

References

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the s back in the corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocirlan, C.E. Environmental workplace behaviors definition matters. Organ. Environ. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, E.; Tosti-Kharas, J.; King, C.E. Empowering employee sustainability: Perceived organizational support toward the environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 128, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girschik, V.; Svystunova, L.; Lysova, E. Internal Activists as Transformers of Csr: A Typology and Research Agenda; EGOS: Tallinn, Estonia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Paillé, P.; Raineri, N. Linking perceived corporate environmental policies and employees eco-initiatives: The influence of perceived organizational support and psychological contract breach. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, A.; Blazejewski, S.; Dittmer, F. The more, the merrier: Why and how employee-driven eco-innovation enhances environmental and competitive advantage. Sustainability 2016, 8, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.H.; Peters, G.J.Y.; Kok, G. A review of determinants of and interventions for pro-environmental behaviors in organizations. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2933–2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; De Young, R.; Marans, R.W. Factors influencing individual recycling behavior in office settings a study of office workers in taiwan. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 380–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, T.; Barr, S.; Gilg, A. A tale of two locational settings: Is there a link between pro-environmental behaviour at work and at home? Local Environ. 2007, 12, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S. Green identity, green living? The role of pro-environmental self-identity in determining consistency across diverse pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Werff, E.; Steg, L.; Keizer, K. The value of environmental self-identity: The relationship between biospheric values, environmental self-identity and environmental preferences, intentions and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D.; Grant, D. “Hippies on the third floor”: Climate change, narrative identity and the micro-politics of corporate environmentalism. Organ. Stud. 2012, 33, 1451–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, H.; Russell, S.V.; Fielding, K. Corporate environmentalism and top management identity negotiation. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2012, 25, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, S.; Marshall, J.; Easterby-Smith, M. Living with contradictions: The dynamics of senior managers’ identity tensions in relation to sustainability. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 328–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, L.; Guerci, M. ‘Activists in a suit’: Paradoxes and metaphors in sustainability managers’ identity work. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 148, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kira, M.; Balkin, D.B. Interactions between work and identities: Thriving, withering, or redefining the self? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2014, 24, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; LoBuglio, N.; Dutton, J.E.; Berg, J.M. Job crafting and cultivating positive meaning and identity in work. In Advances in Positive Organizational Psychology; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2013; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- Meister, A.; Jehn, K.A.; Thatcher, S.M. Feeling misidentified: The consequences of internal identity asymmetries for individuals at work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2014, 39, 488–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, N.P.; Ramarajan, L. Checking your identities at the door? Positive relationships between nonwork and work identities. In Exploring Positive Identities and Organizations. Building a Theoretical and Research Foundation; Roberts, L.M., Dutton, J.E., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvaja, M. Tensions and striving for coherence in an academic’s professional identity work. Teach. High. Educ. 2018, 23, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveningsson, S.; Alvesson, M. Managing managerial identities: Organizational fragmentation, discourse and identity struggle. Hum. Relat. 2003, 56, 1163–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.D. Identities and identity work in organizations. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H.; Barbulescu, R. Identity as narrative: Prevalence, effectiveness, and consequences of narrative identity work in macro work role transitions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, C.A.; Brown, A.D.; Hailey, V.H. Working identities? Antagonistic discursive resources and managerial identity. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 323–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.J. Managing identity: Identity work, personal predicaments and structural circumstances. Organization 2008, 15, 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.J. Narrative, life story and manager identity: A case study in autobiographical identity work. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M. Self-doubters, strugglers, storytellers, surfers and others: Images of self-identities in organization studies. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, S.M. Ideal selves as resources for the situated practice of identity. Manag. Commun. Q. 2010, 24, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beech, N.; MacIntosh, R.; McInnes, P. Identity work: Processes and dynamics of identity formations. Int. J. Public Adm. 2008, 31, 957–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlile, P.R. Artifacts and Knowledge Negotiation across Domains; Rafaeli, A., Pratt, M.G., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Golden-Biddle, K.; Reay, T.; Denis, J.L.; Hébert, Y.; Lamothe, L.; Gervais, J. Identity struggles in merging organizations: Renegotiating the sameness-difference dialectic. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2012, 48, 135–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Rockmann, K.W.; Kaufmann, J.B. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, Z.; Vecchi, B. Identity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, A. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age; Stanford university press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.G.; Corley, K.G. Managing multiple organizational identities: On identity ambiguity, identity conflict, and members’ reactions. In Identity and the Modern Organization; Bartel, C.A., Blader, S., Wrzesniewski, A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, N.; Ybema, S. Marketing identities: Shifting circles of identification in inter-organizational relationships. Organ. Stud. 2010, 31, 279–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyberg, D.; Sveningsson, S. Paradoxes of authentic leadership: Leader identity struggles. Leadership 2014, 10, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. On being green and being enterprising: Narrative and the ecopreneurial self. Organization 2013, 20, 794–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Robertson, M. Money matters: Teflonic identity manoeuvring in the investment banking sector. Organ. Stud. 2016, 37, 7–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E. Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Grant, A.M.; Johnson, V. When callings are calling: Crafting work and leisure in pursuit of unanswered occupational callings. Organ. Sci. 2010, 21, 973–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabram, K.; Maitlis, S. Negotiating the challenges of a calling: Emotion and enacted sensemaking in animal shelter work. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 584–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M.; Bakker, A.B.; Derks, D. Development and validation of the job crafting scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Roberts, L.M.; Bednar, J. Pathways for positive identity construction at work: Four types of positive identity and the building of social resources. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2010, 35, 265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Kornberger, M.; Brown, A.D. Ethics’ as a discursive resource for identity work. Hum. Relat. 2007, 60, 497–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt, E.N. Exploring environmental identity and behavioral change in an environmental science course. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2013, 8, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsi, M.; Andriopoulos, C.; Lewis, M.W.; Ingram, A.E. Managing creatives: Paradoxical approaches to identity regulation. Hum. Relat. 2010, 63, 781–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Lee Ashcraft, K.; Thomas, R. Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organization 2008, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucius-Hoene, G.; Deppermann, A. Rekonstruktion Narrativer Identität. Ein Arbeitsbuch zur Analyse Narrativer Interviews; Leske+Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gioia, D.A.; Corley, K.G.; Hamilton, A.L. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, C.; Weseler, D.; Kostova, P. When and why do individuals craft their jobs? The role of individual motivation and work characteristics for job crafting. Hum. Relat. 2016, 69, 1287–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J. Crafting a balance between work and home. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1539–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, J. Qualitative Interviewforschung, 2nd ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, A.; Unwin, L. Job crafting and identity in low-grade work: How hospital porters redefine the value of their work and expertise. Vocat. Learn. 2017, 10, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Funktionen und Folgen Formaler Organisation; HeinOnline: Buffalo, NY, USA, 1964; Volume 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman, A.O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1970; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Tams, S.; Marshall, J. Responsible careers: Systemic reflexivity in shifting landscapes. Hum. Relat. 2011, 64, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in corporate sustainability: Towards an integrative framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramarajan, L.; Reid, E. Shattering the myth of separate worlds: Negotiating nonwork identities at work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipp, T.; Demerouti, E. Which employees craft their jobs and how? Basic dimensions of personality and employees’ job crafting behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 631–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrou, P.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1766–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, P.M.; Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. Better? Job Crafting for Sustainable Employees and Organizations. Intr. Work Organ. Psych. Inter. Perspect. 2017, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

| Actors in Focus | Identity Work Strategies/Positions | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainability managers | Self-narratives and discourses resisting and/or enabling green identities, e.g., green change agent, rational manager, committed activist | Wright, Nyberg, and Grant [13]; Cherrier, Russel, and Fielding [40] |

| Metaphors help to make sense of green identity tensions | Carollo and Guerci [16] | |

| Top managers | Deflect and distance green identity tensions through rationalization and legitimization | Allen, Marshall, and Easterby-Smith [15]; Alvesson and Robertson [41] |

| Identity Work Strategy | First Order Categories | Exemplary Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Exposing | display green attitudes | “Back when I started to work for [my company], I did support for a lot of nuclear power plants, had no problem with that at all. And that became a problem for me. (…) Meanwhile I have no inhibitions at all anymore from carrying a “Nuclear Power—no thanks!” sticker on my bike. (…). Well, but we do support for nuclear power plants and that gradually did become more and more of a problem for me.” (Richard) |

| actively resist | “At that time, I asked [my supervisor], Mr. […], what should I do with the sulfuric acid? [He said]: ‘Put it in the refuse container outside’. And I said: ‘No, I won’t do that, even if you would dismiss me […]. At that time I started to make war with him.” (Elisabeth) | |

| Enduring | accept non-resolution | “And I think other colleagues are shaking their heads and think: What is going on with her? (…). With one colleague I had a heated discussion about coffee capsules. They are a red rag to me (…). I find it absolutely (…) an incredible environmental sin (…): Well that [discussion] stayed unsolved: He continues to buy coffee capsules and I continue to buy my fair-trade coffee.” (Sara) |

| postpone | “And you have to have such a, how would you say, resilience. So again and again, okay, that doesn’t work/can’t be done/is impossible, a pity, let’s do something new. That doesn’t work either. (…) No? And then it goes on and on like this and after the hundredth time.” (Megan) | |

| Do not let up | “I will try this again and again. Because it is my personal conviction. And as long as I can influence this, I will also do that.” (Sara) | |

| Dodging | hidden green action | “So I went a little beyond my competences now. […] But by complying with the [company] rules, it doesn’t work, if you stick to all formalities, nothing ever gets done. […] If you really comply with all of how it is written, that’s actually worth nothing.” (Scott) |

| building niches | “I have told some colleagues about the things I am doing in this [project] in [foreign country]. Some colleagues are now regularly donating money for the project. I have set up a standing order for them. […] I also have a few fair-trade chocolate bars at my workplace that everyone can buy. And the money that remains goes to the project in [foreign country]. From time to time, I also talk about how coffee or chocolate is produced.” (Richard) | |

| Dissolving | changing roles or employers | “And then that was a new energy supplier on a greenfield site. And then, there, I had the freedom to do everything in a way like I’ve had in my mind for a long time. That you’d do it the right way. There was no moron who would dictate something to me.” (Patrick) |

| Starting up green | “That was in 20XX, when I stopped working for [Company X], went into early retirement, and, after that, since then, I am on the road as an independent consultant and try to counsel solar-energy or wind-energy companies. (…) and I made a profession out of my calling, yes.” (William) | |

| shift engagement | “I’ve reduced my working hours a bit, because I think, that is my strategy […]. Well, so I’ve made my peace with it and work is for […], yes, to earn money. But, yes, I believe I’ve shifted a lot of my engagement towards my private life. Yes, it’s like two worlds, right? The one is for business, and how I live my private life is just very different.“ (Rachel) |

| Resources for Identity Work | organization as green lever | “Well, I say, privately, when I place myself on the streets and hold up a poster: ‘Don’t waste mobiles!’, they would say: ‘What does he want from me?’ But assuming I do [my initiatives at work] another five years and that has some influence, […] that those are billions, where you could save billions of dollars, where you could basically save waste with that. And that is, with such a huge corporation, an enormous lever, if it works.” (Sean) |

| lone fighter | “Who is committed, exposes oneself. And therefore takes a risk. That can offer chances to find recognition as a pioneer, as an expert, as an innovator—maybe to be able to actually achieve something—but there are also risks. Some may consider you a wise guy, an exotic, or a disturber.” (Taylor) | |

| network of the few | “[It is] mainly about hanging on and taking along those, of course, who are interested or, let’s say, those where you notice, they are interested in supporting it, too, and that they also do something. That was very important.“ (Scott) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Blazejewski, S.; Dittmer, F.; Buhl, A.; Barth, A.S.; Herbes, C. “That is Not What I Live For”: How Lower-Level Green Employees Cope with Identity Tensions at Work. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145778

Blazejewski S, Dittmer F, Buhl A, Barth AS, Herbes C. “That is Not What I Live For”: How Lower-Level Green Employees Cope with Identity Tensions at Work. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145778

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlazejewski, Susanne, Franziska Dittmer, Anke Buhl, Andrea Simone Barth, and Carsten Herbes. 2020. "“That is Not What I Live For”: How Lower-Level Green Employees Cope with Identity Tensions at Work" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145778

APA StyleBlazejewski, S., Dittmer, F., Buhl, A., Barth, A. S., & Herbes, C. (2020). “That is Not What I Live For”: How Lower-Level Green Employees Cope with Identity Tensions at Work. Sustainability, 12(14), 5778. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145778