Commuting and the Motherhood Wage Gap: Evidence from Germany

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Transition to Parenthood and Commuting Behavior

2.2. Reduction in Commuting Distance and the Motherhood Wage Gap

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Approach

4. Results

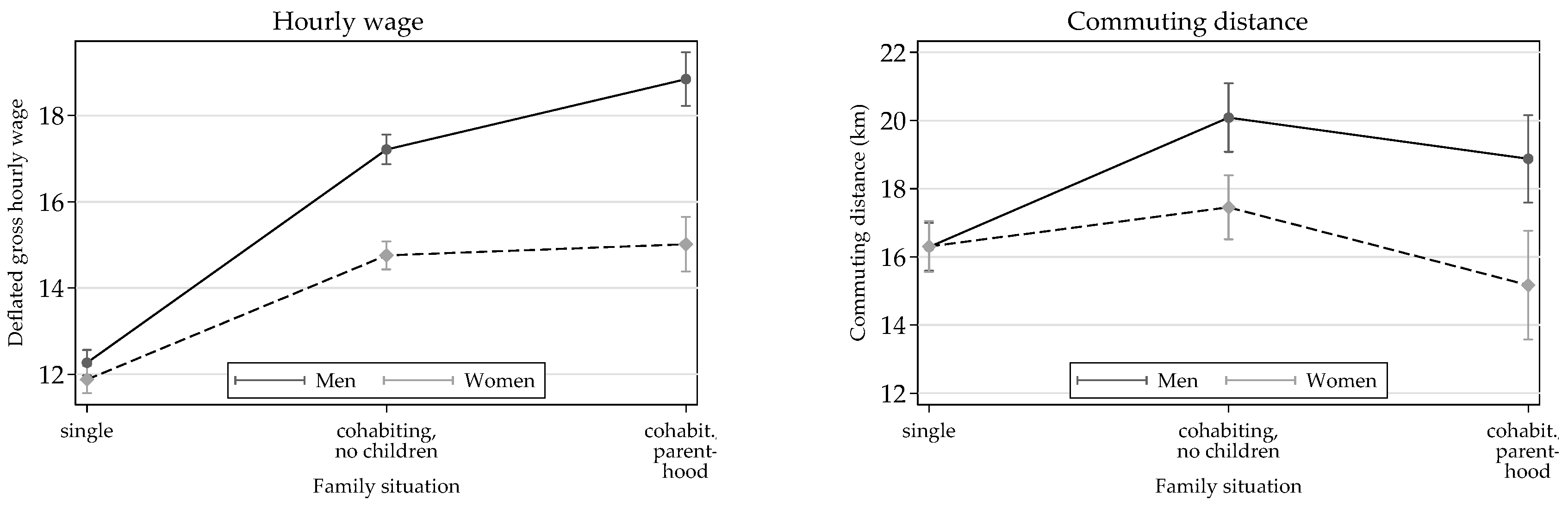

4.1. Descriptive Findings

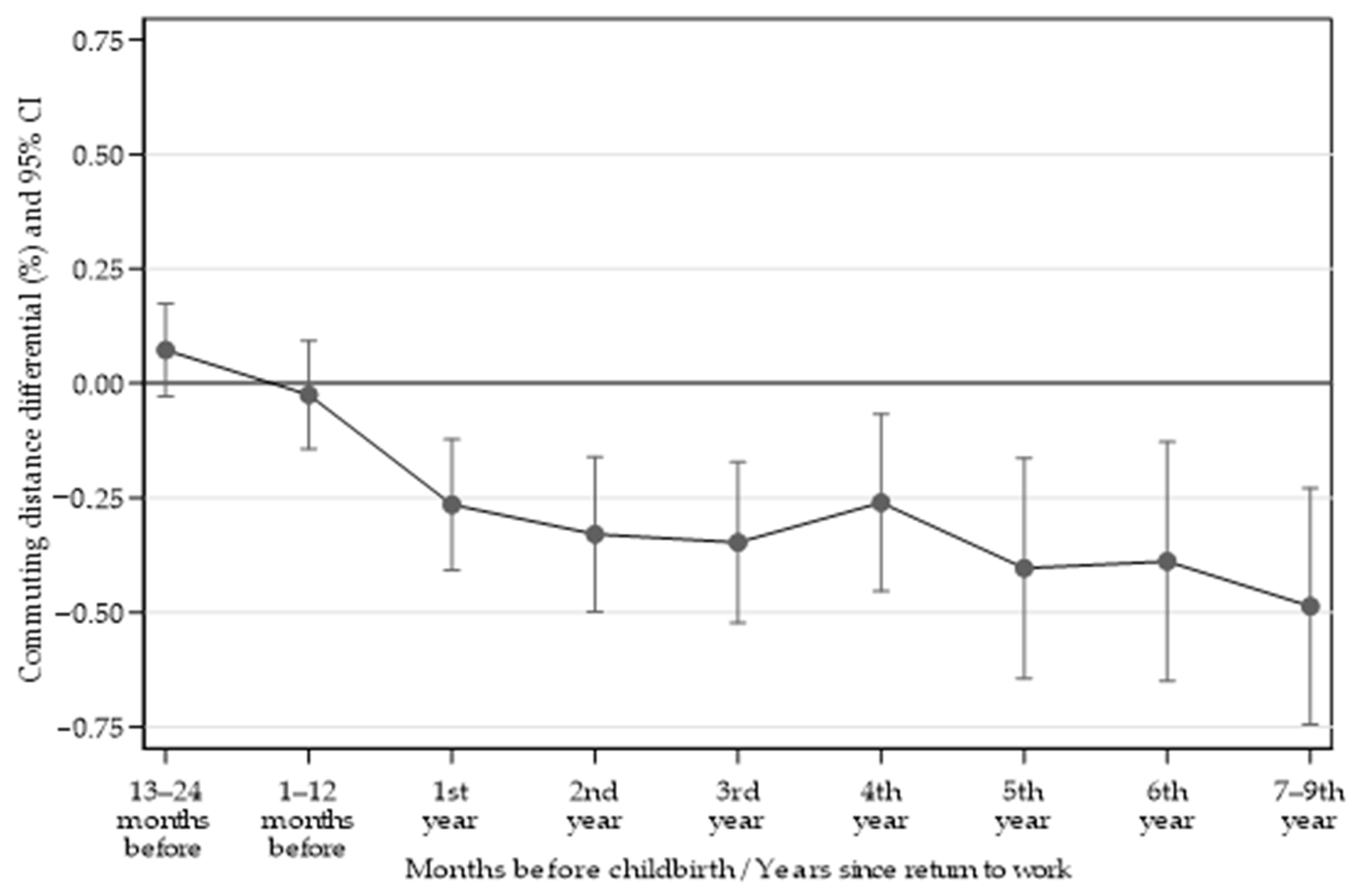

4.2. Transition to Parenthood and Commuting Distance of Women and Men

4.3. Transition to Parenthood, Commuting Distance Adjustments and the Wage Penalty for Motherhood

4.4. Tracing the Mechanisms behind the Wage Penalty for Mothers Who Reduce Their Commuting

4.5. Robustness Checks

5. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Transition to parenthood | 0.087 *** |

| Age | 0.201 *** |

| Age squared | −0.002 *** |

| GDP growth | −0.001 |

| Living in East Germany | −0.167 *** |

| Living in a rural region | −0.040 |

| Partnership status (ref. = single) | |

| Cohabiting | 0.053 *** |

| Married | 0.030 + |

| Distance reduction after childbirth via moving a | 0.066 |

| Distance reduction after childbirth via job change a | −0.214 ** |

| Distance reduction after childbirth, whereby both events (moving and job change) may have contributed to this change a | −0.123 |

| Distance reduction after childbirth, but neither a move nor a job change is connected to it in the data a | −0.061 |

| Within-R squared | 0.220 |

| Observations | 18,726 |

| Persons | 3294 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transition to parenthood | −0.113 *** | −0.110 *** | −0.064 *** | −0.087 *** |

| Age | 0.200 *** | 0.200 *** | 0.189 *** | 0.201 *** |

| Age squared | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** |

| GDP growth | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| Living in East Germany | −0.163 ** | −0.164 *** | −0.161 ** | −0.164 *** |

| Living in a rural region | −0.041 | −0.042 | −0.044 | −0.039 |

| Partnership status (ref. = single) | ||||

| Cohabiting | 0.054 *** | 0.053 *** | 0.048 *** | 0.053 *** |

| Married | 0.032 * | 0.030 + | 0.024 | 0.030 + |

| Commuting distance (log) | 0.009 + | |||

| Increasing commuting distancebefore parenthood a | 0.063 *** | |||

| Reducing commuting distancebefore parenthood a | 0.034 * | |||

| Increasing commuting distanceafter childbirth a | −0.038 | |||

| Reducing commuting distanceafter childbirth a | −0.092 ** | −0.097 ** | ||

| Within-R squared | 0.217 | 0.218 | 0.221 | 0.218 |

| Observations | 18,726 | |||

| Persons | 3294 | |||

References

- Blau, F.D.; Kahn, L.M. Women’s Work and Wages. In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics; Macmillan, P., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, F.D.; Kahn, L.M. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations. J. Econ. Lit. 2017, 55, 789–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Federal Statistical Office. Gender Pay Gap 2019: Frauen verdienten 20% weniger als Männer. Verdienstunterschied bei 4,44 Euro brutto pro Stunde. Press release No. 097 of 16 March 2020. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2020/03/PD20_097_621.html (accessed on 26 March 2020).

- Gartner, H.; Hinz, T. Geschlechtsspezifische Lohnungleichheit in Betrieben, Berufen und Jobzellen (1993–2006). Berl. J. Soziologie 2009, 19, 557–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, V.; Groß, M. The just gender pay gap in Germany revisited: The male breadwinner model and regional differences in gender-specific role ascriptions. Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 2020, 65, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldfogel, J. Understanding the ‘Family Gap’ in Pay for Women with Children. J. Econ. Perspect. 1998, 12, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polachek, S.W. How the Life-Cycle Human Capital Model Explains Why the Gender Wage Gap Narrowed. In The Declining Significance of Gender? Blau, F.D., Brinton, M.C., Grusky, D.B., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 102–124. [Google Scholar]

- Budig, M.J.; England, P. The Wage Penalty for Motherhood. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2001, 66, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangl, M.; Ziefle, A. Motherhood, Labor Force Behavior, and Women’s Careers: An Empirical Assessment of the Wage Penalty for Motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Demography 2009, 46, 341–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühhirt, M.; Ludwig, V. Domestic Work and the Wage Penalty for Motherhood in West Germany. J. Marriage Fam. 2012, 74, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejrnæs, M.; Kunze, A. Work and Wage Dynamics around Childbirth. Scand. J. Econ. 2013, 115, 856–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühhirt, M. Childbirth and the Long-Term Division of Labour within Couples: How do Substitution, Bargaining Power, and Norms affect Parents’ Time Allocation in West Germany? Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 28, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechant, A.; Rost, H.; Schulz, F. Die Veränderung der Hausarbeitsteilung in Paarbeziehungen. Ein Überblick über die Längsschnittforschung und neue empirische Befunde auf Basis der pairfam-Daten. ZfF–Z. Für Fam./J. Fam. Res. 2014, 26, 144–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solera, C.; Mencarini, L. The gender division of housework after the first child: A comparison among Bulgaria, France and the Netherlands. Community Work. Fam. 2018, 21, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felfe, C. The motherhood wage gap: What about job amenities? Labour Econ. 2012, 19, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, D.; Ponthieux, A.P. Child-related Career Interruptions and the Gender Wage Gap in France. Ann. Econ. Stat. 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmond, P.; McGuinness, S. The Gender Wage Gap in Europe: Job Preferences, Gender Convergence and Distributional Effects. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2018, 81, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, J.F.; Chiu, L.-C. The Wage Effects of Residential Location and Commuting Constraints on Employed Married Women. Urban Stud. 1990, 27, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semyonov, M.; Lewin-Epstein, N. Suburban Labor Markets, Urban Labor Markets, and Gender Inequality in Earnings. Sociol. Q. 1991, 32, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, F.M.; Bronson, D.R. The Journey to Work and Gender Inequality in Earnings: A Cross-Validation Study for the United States. Sociol. Q. 1996, 37, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.W. The commute to work and the gender wage differential. International analyses. In Wages and Employment: Economics, Structure and Gender Differences; Mukhergee, A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Auspurg, K.; Schönholzer, T. An Heim und Herd gebunden?/Tied to Home and Children? Z. für Soziol. 2013, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, F. Commuting Patterns, the Spatial Distribution of Jobs and the Gender Pay Gap in the U.S. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Barbanchon, T.; Rathelot, R.; Roulet, A. Gender Differences in Job Search: Trading off Commute against Wage. SSRN. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3467750 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Nafilyan, V. Gender Differences in Commute Time and Pay: A Study into the Gender Gap for Pay and Commuting Time, Using Data from the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings; Office for National Statistics: London, UK, 2019. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/genderdifferencesincommutetimeandpay/2019-09-04 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Fan, Y. Household structure and gender differences in travel time: Spouse/partner presence, parenthood, and breadwinner status. Transportation 2015, 44, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Nadal, J.I.; Molina, J.A. Commuting Time and Household Responsibilities: Evidence Using Propensity Score Matching. J. Reg. Sci. 2016, 56, 332–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüger, H.; Feldhaus, M.; Becker, K.S.; Schlegel, M. Zirkuläre berufsbezogene Mobilität in Deutschland. Vergleichende Analysen mit zwei repräsentativen Surveys zu Formen, Verbreitung und Relevanz im Kontext der Partnerschafts- und Familienentwicklung. Comp. Popul. Stud. 2011, 36, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiḷ, G. Job Mobility and Family Life. In Mobile Living Across Europe II: Causes and Consequences of Job-Related Spatial Mobility in Cross-National Comparison; Schneider, N.F., Collet, B., Eds.; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 2010; pp. 215–236. [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid, R.; Chen, T. Commuting times—The role of gender, children and part-time work. Res. Transp. Econ. 2012, 34, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ommeren, J.; Rietveld, P.; Nijkamp, P. Commuting: In Search of Jobs and Residences. J. Urban Econ. 1997, 42, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ommeren, J.; Fosgerau, M. Workers’ marginal costs of commuting. J. Urban Econ. 2009, 65, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüger, H.; Pfaff, S.; Weishaar, H.; Wiernik, B.M. Does perceived stress mediate the relationship between commuting and health-related quality of life? Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2017, 50, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, K.A. Urban Transportation Economics; Harwood: Chur, Switzerland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg, G.J.; Gorter, C. Job Search and Commuting Time. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 1997, 15, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouwendal, J. Spatial job search and commuting distances. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 1999, 29, 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouwendal, J.; Nijkamp, P. Living in Two Worlds: A Review of Home-to-Work Decisions. Growth Chang. 2004, 35, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, L.C. Gender, Time and Inequality: Trends in Women’s and Men’s Paid Work, Unpaid Work and Free Time. Soc. Forces 2005, 84, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skopek, J.; Leopold, T. Explaining Gender Convergence in Housework Time: Evidence from a Cohort-Sequence Design. Soc. Forces 2018, 98, 578–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J.; Stanfors, M. It’s About Time! Gender, Parenthood, and Household Divisions of Labor under Different Welfare Regimes. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 35, 1066–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, M. Gender, the Home-Work Link, and Space-Time Patterns of Nonemployment Activities. Econ. Geogr. 1999, 75, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lersch, P.; Kleiner, S. Coresidential Union Entry and Changes in Commuting Times of Women and Men. J. Fam. Issues 2016, 39, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston-Anumonwo, I. The Influence of Household Type on Gender Differences in Work Trip Distance. Prof. Geogr. 1992, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, T.; Niemeier, D. Travel to work and household responsibility: New evidence. Transportation 1997, 24, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.; Johnston, I. Gender differences in work-trip length: Explanations and implications. Urban Geogr. 1985, 6, 193–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.R.; Joyce, M.S. The Effects of Race and Family Structure on Women’s Spatial Relationship to the Labor Market. Sociol. Inq. 2004, 74, 411–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.J. Sex differences in urban commuting patterns. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 368–372. [Google Scholar]

- Singell, L.D.; Lillydahl, J.H. An Empirical Analysis of the Commute to Work Patterns of Males and Females in Two-Earner Households. Urban Stud. 1986, 23, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagnani, J. Women’s commuting patterns in the Paris region. Tijdschr. voor Econ. en Soc. Geogr. 1983, 74, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; McDonald, J.F. Determinants of Commuting Time and Distance for Seoul Residents: The Impact of Family Status on the Commuting of Women. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 1283–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N.F.; Ruppenthal, S.; Lück, D.; Rüger, H.; Dauber, A. Germany – A Country of Locally Attached but Highly Mobile People. In Mobile Living Across Europe I: Relevance and Diversity of Job-Related Spatial Mobility in Six European Countries; Schneider, N.F., Meil, G., Eds.; Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen-Opladen, 2008; pp. 105–148. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, M.; Nisic, N. Regionale Bindung, räumliche Mobilität und Arbeitsmarkt—Analysen für die Schweiz und Deutschland. Schweiz. Z. Soziologie 2007, 33, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Skora, T. Pendelmobilität und Familiengründung. Zum Zusammenhang von berufsbedingtem Pendeln und dem Übergang zum ersten Kind; Barbara Budrich: Opladen, Germany; Berlin, Germany; Toronto, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mincer, J.; Ofek, H. Interrupted Work Careers: Depreciation and Restoration of Human Capital. J. Hum. Resour. 1982, 17, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukrowska-Torzewska, E.; Matysiak, A. The motherhood wage penalty: A meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Res. 2020, 88–89, 102416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, T.J.; Kiefer, N.M. The empirical status of job search theory. Labour Econ. 1993, 1, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, A. Job Search Theory; Handbook of Regional Science; Fischer, M.M., Nijkamp, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar]

- Van Ham, M. Workplace mobility and occupational achievement. Int. J. Popul. Geogr. 2001, 7, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büchel, F.; Battu, H. The Theory of Differential Overqualification: Does it Work? Scott. J. Politi. Econ. 2003, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R.H. Why Women Earn Less: The Theory and Estimation of Differential Overqualification. Am. Econ. Rev. 1978, 68, 360–373. [Google Scholar]

- Ofek, H.; Merrill, Y. Labor immobility and the formation of gender wage gaps in local markets. Econ. Inq. 1997, 35, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmer, F.; Möller, J. Interrelations between the urban wage premium and firm-size wage differentials: A microdata cohort analysis for Germany. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2009, 45, 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, C.H.; Van Ham, M. Migration histories and occupational achievement. Popul. Space Place 2005, 11, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viry, G.; Rüger, H.; Skora, T. Migration and Long-Distance Commuting Histories and Their Links to Career Achievement in Germany: A Sequence Analysis. Sociol. Res. Online 2014, 19, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, A. The real thin theory: Monopsony in modern labour markets. Labour Econ. 2003, 10, 105–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisic, N. Smaller Differences in Bigger Cities? Assessing the Regional Dimension of the Gender Wage Gap. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 33, 292–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebel, J.; Grabka, M.M.; Liebig, S.; Kroh, M.; Richter, D.; Schröder, C.; Schupp, J. The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Jahrbücher Natl. Stat. 2019, 239, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüderl, J.; Ludwig, V. Fixed-Effects Panel Regression. In The Sage Handbook of Regression Analysis and Causal Inference; Best, H., Wolf, C., Eds.; Sage Reference: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 327–358. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, R.J.; Innes, J.T. Interpreting semilogarithmic regression coefficients in labor research. J. Labor Res. 1989, 10, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, R.J. Flexible Working Hours, Family Responsibilities, and Female Self-Employment. Am. J. Econ. Sociol. 1999, 58, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budig, M.J. Gender, Self-Employment, and Earnings: The Interlocking Structures of Family and Professional Status. Gend. Soc. 2006, 20, 725–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P.D. Fixed Effects Regression Models; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, C. The Marriage Earnings Premium as a Distributed Fixed Effect. J. Hum. Resour. 2006, 41, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüger, H.; Viry, G. Work-related Travel over the Life Course and Its Link to Fertility: A Comparison between Four European Countries. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 33, 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mothers | Childless Women | Fathers | Childless Men | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Commuting distance in km | 14.56 | 16.09 | 16.88 | 18.67 | 18.74 | 18.49 | 17.82 | 19.73 |

| Deflated hourly wages in Euro a | 14.73 | 6.96 | 13.32 | 6.78 | ||||

| Reduction of commuting distance after childbirth a | 0.29 | |||||||

| Human capital a | ||||||||

| Work experience full-time and part-time (years) | 20.39 | 10.43 | 17.70 | 15.09 | ||||

| Firm tenure (years) | 6.80 | 5.75 | 5.93 | 6.23 | ||||

| Qualification (mis-)match a | ||||||||

| poor job match | 0.22 | 0.23 | ||||||

| Job characteristics a | ||||||||

| Firm with 1–4 employees | 0.10 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Firm with 5–19 employees | 0.21 | 0.20 | ||||||

| Firm with 20–99 employees | 0.20 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Firm with 100–199 employees | 0.09 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Firm with 200–1999 employees | 0.19 | 0.21 | ||||||

| Firm with 2000 or more employees | 0.22 | 0.23 | ||||||

| Self-employment | 0.04 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Single (not living with a partner) | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.04 | 0.60 | ||||

| Cohabiting | 0.24 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.22 | ||||

| Married | 0.63 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.19 | ||||

| Living in Eastern Germany | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.20 | ||||

| Living in a rural region | 0.39 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.31 | ||||

| Age | 34.61 | 5.25 | 31.09 | 8.12 | 35.79 | 5.60 | 31.83 | 8.22 |

| n Observations | 1649 | 17,077 | 2792 | 19,593 | ||||

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Transition to parenthood | −0.327 *** | −0.026 |

| Age | 0.036 + | 0.032 + |

| Age squared | −0.001 + | −0.000 + |

| GDP growth | 0.001 | −0.000 |

| Living in East Germany | 0.127 | −0.181 |

| Living in a rural region | 0.170 | 0.215 |

| Partnership status (ref. = single) | ||

| Cohabiting | 0.110 ** | 0.130 ** |

| Married | 0.168 ** | 0.111 * |

| Within-R squared | 0.010 | 0.004 |

| Observations | 18,726 | 22,385 |

| Persons | 3294 | 3889 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Transition to parenthood | −0.113 *** | −0.087 *** |

| Age | 0.200 *** | 0.201 *** |

| Age squared | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** |

| GDP growth | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| Living in East Germany | −0.163 ** | −0.164 *** |

| Living in a rural region | −0.041 | −0.039 |

| Partnership status (ref. = single) | ||

| Cohabiting | 0.054 *** | 0.053 *** |

| Married | 0.032 * | 0.030 + |

| Reducing commuting distanceafter childbirth a | −0.097 ** | |

| Within-R squared | 0.217 | 0.218 |

| Observations | 18,726 | |

| Persons | 3294 | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No job change after childbirth | −0.092 *** | −0.029 | −0.038 + | −0.037 + | −0.037 + | −0.037 + |

| Job change with reduction of commuting after childbirth a | −0.223 ** | −0.196 ** | −0.155 * | −0.104 | −0.091 | −0.021 |

| Job change without reduction of commuting after childbirth | −0.037 | −0.009 | 0.032 | 0.041 | 0.047 | 0.088 + |

| Controls and explanatory variables | ||||||

| Control variables | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Human capital variables | ||||||

| Labor force experience | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Firm tenure | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Qualification (mis-)match | ||||||

| Changes to poor job matches | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Job characteristics | ||||||

| Changes into self-employment | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Changes to smaller companies | No | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Within-R squared | ||||||

| Observations | 18,726 | |||||

| Persons | 3294 | |||||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Skora, T.; Rüger, H.; Stawarz, N. Commuting and the Motherhood Wage Gap: Evidence from Germany. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145692

Skora T, Rüger H, Stawarz N. Commuting and the Motherhood Wage Gap: Evidence from Germany. Sustainability. 2020; 12(14):5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145692

Chicago/Turabian StyleSkora, Thomas, Heiko Rüger, and Nico Stawarz. 2020. "Commuting and the Motherhood Wage Gap: Evidence from Germany" Sustainability 12, no. 14: 5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145692

APA StyleSkora, T., Rüger, H., & Stawarz, N. (2020). Commuting and the Motherhood Wage Gap: Evidence from Germany. Sustainability, 12(14), 5692. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145692