Abstract

Sustainability describes a means to satisfy the needs of today’s generation without causing suffering to the needs and standards of living of future generations. The concept of sustainability consists of three pillars: economic, environmental, and social. The purpose of this study is to find a link between Corporate Social Responsibility and the Environmental Management System and its impact on the economic results of the researched companies. Many companies expect to increase their profits through Corporate Social Responsibility behavior and Environmental Management System certification. Based on an analysis of data collected from 200 of the largest firms operating in various industries in the Slovak Republic, we observed the implications of these two management tools and their impacts on the economic results of these companies. To verify individual hypotheses, we use well-established methods, specifically the Pearson Chi-square test, the Mann-Whitney U test, and the Kruskal-Wallis test, along with the Statistica software. The results suggest a relationship between the incorporation of these two management tools and that incorporation of the Corporate Social Responsibility has an impact on company profit. This work contributes to the literature on sustainability, corporate social behavior, and environmental certification in firms operating in various sectors of the national economy.

1. Introduction

Many researchers and firm managers are interested in corporate sustainability management, which describes the managerial objective to achieve sustainability of the firm in the economic, environmental, and societal circumstances that can affect firm behavior [1]. One of the ways to accept these circumstances is to implement some active management tools [2], such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Environmental Management System (EMS). Companies often expect to increase their profits through CSR behavior and EMS certification, as noted by Ong at al. [3]. CSR is a management concept through which companies implement both social and environmental matters in their business operations. Proper implementation of the CSR concept can provide a variety of competitive advantages, such as extended access to capital and markets, increased sales and profits, or cost savings [4]. CSR is accepted as an indicator of the success of a company as a whole, and as a possible way to achieve sustainable development [5]. Noh [6] noted that Environmental management has shown its potential to improve firms’ financial benefits beyond CSR. Enterprises consider environmental activities as a possible way to reduce costs. These activities may affect cost reduction, improve corporate image, and provide better opportunities for exporting and strengthening a firm’s competitive advantage together with reducing its environmental effects [7]. Business firms are increasingly certifying environmental management as a business strategy to accept environmental challenges and facilitate a shift to green market competition [3]. The world’s most successful EMS standard is considered to be ISO 14001. ISO 14001 is a harmonized environmental standard that has the potential to improve firm performance. Organizations may reduce their costs and improve their production processes by implementing green strategies [8]. According to an early survey, presented by Cornoglio and Botta [9], the firms that have attained a level of ISO 14001 certification are not only more environmentally responsible but also more efficient. The purpose of environmental management is to develop, implement, manage, coordinate, and monitor corporate environmental activities. Environmental innovation and environmental performance can then emerge as an outcome of environmental management [3]. This work contributes to the literature on sustainability, corporate social behavior, and environmental certification in firms operating in various sectors of the national economy. Due to the research focus of the funding agencies and the main goals of the scientific grants supporting this research, we focus our study on Slovak companies. The principal aim of this article is to determine whether the implementation of CSR and EMS certification (ISO 14001) (either externally or mutually) influences the economic results of the researched companies. The secondary objective is to observe the incorporation of these two management tools in various sectors of the national economy.

2. Theoretical Background

Sustainability branches into three dimensions: economic, environmental, and social. Its principles are defined as social progress that respects all needs, offers effective environmental protection, and allows for the friendly use of natural resources by maintaining a high and stable level of economic growth and employment [10,11].

2.1. CSR

CSR and sustainability are characteristics that describe the social and environmental benefits and implications of business activities. Some studies reviewing common definitions of these two terms have indicated that their meanings are close and they are used similarly. However, CSR is usually defined more generally and normatively. The aim of the CSR is to change company behavior, moving it towards sustainability [12]. CSR states that it is the responsibility of the company to eliminate negative effects on society and evaluate long-term beneficial effects [13]. CSR has gained global awareness in recent years. Supporters of the CSR say that a good reputation may be beneficial for firms [14]. On the other hand, Friedman [15] stated that managers are responsible for abiding by the law and respecting general ethical principles and their goal is to maximize the firm’s profits. According to him, the government has to define property rights with no external effects and no differences in private and social costs. The CSR represents a voluntary effort of companies that exceeds the framework of legislation. This requires the intensive involvement of all of the important partners in the everyday activities of firms and institutions [16]. CSR, as a corporate activity, has been highly respected in recent years, and organizations all around the world are increasingly implementing it [17]. The implementation of CSR may be provided by acceptance of the social manners and validation of CSR. Firms may certify their CSR through the IQNet SR10 certification of the social responsibility system. It is important to invest in CSR certification, as in the absence of any mechanism, consumers may not believe firms regarding their social approach [12,18]. Freeman [19] and Jones [20] introduced the concept of strategic CSR in the context of the strategic implementation of the CSR. This concept means that firms seek to go beyond standard practices and perform activities different from the competition. Carroll [21] defined Strategic CSR as a corporate activity that balances social and societal interests. A growing number of studies show that the efficiency results of the CSR depend on how companies implement the CSR. Through the strategic implementation of the CSR, companies not only increase the value of their shareholders but also contribute to the company’s sustainability [22]. Strategic CSR fulfills the responsibilities for social care. It establishes mutually advantageous situations for both society and the stakeholder group [23]. According to Bowman and Haire [24], CSR describes the strategic activity of a company that changes the perception of society through the world outside and effects its business efficiency.

CSR Models

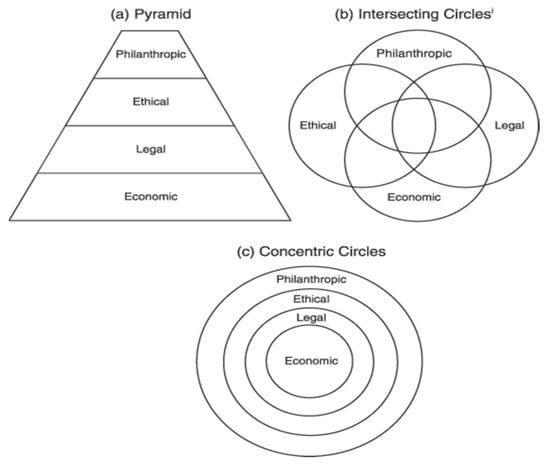

The Carrol CSR pyramid (Figure 1a) presents a simple framework that explains arguments about the social obligations of companies. Key characteristics of the Carrol CSR pyramid are the following: (i) The CSR is based on the profit principle, (ii) the subsequent reference is based on confidence that all activities are in accordance with all laws and regulations, and (iii) before the company considers its philanthropic options, it has to fulfill their ethical obligations [25]. The intersecting circles (IC) model of the CSR (Figure 1b) differs from the pyramid model in two main ways: (i) it identifies the option of relationships among CSR domains, and (ii) it disclaims the hierarchy of importance [26,27]. The concentric circle model is the same as the pyramid model as it accepts the social importance of the economy of business. Moreover, like the IC model, the concentric circle model accentuates the mutual relations between various corporate social responsibilities. The bases of these similarities, however, show significant differences in their definitions of corporate responsibilities.

Figure 1.

(a) Carroll Pyramid for Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR); (b) the intersecting circles model; (c) the concentric circle model. Source: own processing according to [21,26,28,29].

2.2. Environmental Management System

As Rajnoha et al. [30] state, the current changes in turbulent environments require new approaches to business rather than doing business as usual. As the environment worsens, many documents have been signed. These documents have been influenced by praxis and have established the foundations of environmental management. The importance of environmental performance in organizations is becoming increasingly more popular, and environmental challenges are thus becoming significant for successful organizations [31,32]. There are many types of EMSs available. [33]. The best-known standards are ISO 9000 and ISO 14000. These standards are implemented all around the world. While the ISO 9000 series deals with the issue of quality concerns, ISO 14000 solves problems concerned with environmental management [34]. Multinational and domestic companies around the world have accepted EMSs and approved them by the international standards ISO 14001. Moreover, standard European firms are also registering their EMS according to the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS), as presented by Morrow and Rondinelli [35]. These documents follow the same axiom, though different system components are required by different documents. These two systems primarily vary in formal ways. The most important differences in the extents and requirements of EMS and EMAS are shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

The most important differences in the extents and requirements of the Environmental Management System (EMS) and the Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS). Source: own processing according to [36,37].

According to Pesce et al. [38], companies implement ISO 14001 as they perceive a need for a standardized concept of protecting the environment. The basic steps made through ISO 14001 implementation are (i) environmental policy, (ii) planning, (iii) implementation and operation, (iv) checking and corrective action, and (v) management review. These procedures make ISO 14001 so universal that it may be applied in almost any organization around the world. Standard ISO 14001 is built so that it would operate within each existing management systems and improve these systems regarding the principles of good management where they are lacking. As Cheremisinoff [33] states, in this way committees of the ISO formulated an international standard for an EMS.

EMS, ISO 14001

ISO 14001 is the world’s most successful Environmental Management System (EMS) standard. [39]. It is an optional management tool for organizations that considers important environmental aspects by accepting a legal framework. It involves organizational structure, processes, procedures, and sources and results in the achievement and systematic control of organizational environmental behavior. This management system links the protection of the environment to business organizations, focusing on the achievement of both environmental and business goals [40]. ISO 14001 can allow businesses to perform better in many ways. Companies are becoming more competitive as they improve their company image and stakeholder relations [41]. According to Waxin et al. [42], by reducing resource consumption and implementing better waste management, companies certified by EMS can increase their profits. We have chosen ISO 14001 as the reference model because it includes the basic elements of any proper EMS; it is an international EMS standard, and it is being accepted more and more widely throughout the world as the EMS standard.

2.3. Social Responsibility and Environmental Management

Under the constantly evolving pressure of many stakeholders, multinational companies are invited to fulfill their social and environmental responsibilities. Asif et al. [43] define implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as the result of firms that declare an effort to respect stakeholder expectations and a sign that firms are behaving responsibly. Environmental sustainability is required mainly by external stakeholders, and firms are forced to integrate environmental management into their activities [44]. The Environmental Management System (EMS) is a management tool through which firms react to the internationalization of environmental issues and present their positive attitudes toward sustainability [45,46] Dietz et al. [47] and Orlitzky et al. [48] argue that company managers must be able to define how companies can become more socially, responsible, environmentally sustainable, and economically competitive. Even consumers increasingly consider the social and environmental aspects of their buying decisions: A large number of investors make investment decisions based on social screening services, and governments around the world are implementing stricter environmental and social policies [49]. Many scientific publications deal with CSR in terms of adopting environmentally sustainable initiatives e.g., Trendafilova et al. [50], Baughn et al. [51], and Waxin et al. [52]. In response to the global trend of environmental protection and social responsibility, more and more companies have implemented suitable management tools [53].

Thus, Hypothesis H1 is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

We assume that there exists a statistically significant relationship between incorporating CSR and incorporating EMS.

Companies often expect to increase their profits through CSR behavior and EMS certification [3]. Some studies discovered that more socially responsible firms tend to achieve a lower return on their profitability compared with the firms that practice less social responsibility [50]. According to Suganthi [54], another study found out that the implementation of environmental processes improves the relationship between CSR and company efficiency. Other studies have observed the relationship between the environmental behavior of a firm and its profit [8,31,32].

Therefore, Hypothesis H2 is proposed as follows:

Hypothesis 2.

We assume that there exists a statistically significant difference in a company’s profits between the companies that have incorporated both CSR and EMS and those that have incorporated only one of them.

Hypothesis 2a.

We assume that there exists a statistically significant difference in a company’s profits between the companies that have incorporated CSR and those that have not.

Hypothesis 2b.

We assume that there exists a statistically significant difference in a company’s profits between the companies that have incorporated EMS and those that have not.

The inclusion of environmental management tools and CSR has become a corporate, valid, and modern practice in most industries [49]. According to the investigation by KPMG [55], 95% of large global companies from different industries (e.g., minerals, gas, oil, and finance) submit business sustainability projects every year. CSR is an important part of corporate strategy in sectors with growing discrepancies between the firm profit and its social behavior. CSR may improve the firm’s social awareness [56]. Corporate activities, such as CSR and EMS, are differently important among various sectors. These activities possibly increase the value of companies to a greater extent in that materials, financial, and industrial sectors than in other ones [57]. In Slovakian corporate sustainability practices, the most active sectors are technology, telecommunications, and retail companies. These are mostly branches of foreign companies.

In addition, Hypotheses H3–H5 are proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

We assume that CSR is more often incorporated in the selected sectors of the national economy than in other sectors.

Hypothesis 4.

We assume that the EMS is more often incorporated in the selected sectors of the national economy than in other sectors.

Hypothesis 5.

We assume that in the selected sectors of the national economy, both CSR and EMS are more often certified than in other sectors.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

Slovak Republic is and will be an industrial state [58] Our research sample consists of 200 nonfinancial companies from Slovakia that operate in the machinery and equipment industry (13), electricity and energy industry (28), service and business sector (41), construction industry (10), information and communication technology (ICT) sector (11), electrical engineering industry (11), automotive industry (45), transport and storage industry (8), chemicals and plastics-/-cosmetics-/-pharmaceutical and life science industry (CP-/-C-/-PLCS) (12), food processing-/- agriculture, tobacco industry (FP-/-A-/-T) (12), cellulose and paper-/-wood industry (6), and shoe-/healthcare-/-manufacturing (S-/-HC-/-M) industry (3). Thus, we consider 12 groups of Slovakian industries and sectors. We used the purposive sampling method to select our research sample in order to study a particular group of Slovak companies. The sample size used in the present study was compiled in descending order according to the sales in the year 2018. These companies cover almost 81% of all Slovak nonfinancial companies that achieved sales of over 100 million euros, and which had a flawless balance of control of their financial statements. The largest number of companies being from the automotive industry reflects Slovakia’s focus on this type of production.

We used data on the profits of these companies in 2018 (in euros) and information on whether each company’s Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Environmental Management System (EMS) are certified—i.e., incorporated. The value “1” represents a situation where the system is certified; otherwise, we use “0”. Data concerning the information about implementation were gained from the searched companies. We obtained economic data from the FinStat database that acquires data from the Register of Financial Statements of the Slovak Republic. Concerning the type of margin, we focused on the NOPAT. FinStat [59] represents a web portal that focuses on data detecting the financial health of the Slovak companies.

In Table 2, we present descriptive statistics for the profit (loss) in the analyzed companies among the given industries, where “Min” denotes a minimum value obtained in a given industry, “Max” is a maximum value, and “Std. Dev.” represents a standard deviation. The highest variability in profit is in the shoe/healthcare/manufacturing industry; on the other hand, the lowest is in the chemicals and plastic/cosmetic/pharmaceutical and life science industry. The most profitable company belongs to the electricity and energy sector (SPP Bratislava). On the contrary, Plastic Omnium, a company from the automotive industry, recorded the highest loss. The best results are shown by companies from the electricity and energy industry, ICT industry, automotive industry, and cellulose and paper/wood industry.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of profit in 2018 (in euros).

Table 3 gives information about the number of companies in our sample, with CSR and EMS certification. Up to 78% of the 41 companies from the service and business sector have implemented CSR; 80.5% of these companies have EMS, and both systems are found in 68.3%. In our sample, the second largest number of companies is from the automotive industry, only 37.8% of which use CSR: 28.9% of companies have certified EMS, and only 13.3% analyzed companies from the automotive industry include both systems.

Table 3.

Number of companies with certified CSR and EMS.

3.2. Methods

To verify each individual hypothesis, we used well-established methods, specifically the Pearson Chi-square test (Hypotheses 1,3–5), to see whether observed frequencies at each level of one categorical variable are similar to or different from the frequencies we expected at each level of the categorical variable [60], the Mann–Whitney U test (Hypotheses 2, 2a, 2b), to see whether two independent samples were drawn from the same population (or from populations with the same distributions) [61], and the Kruskal–Wallis test (Hypotheses 3–5), to see whether medians of more than two populations are different as well as the Statistica software. Moreover, we computed Dunn’s test for stochastic dominance, which that reports the results among multiple pairwise comparisons after a Kruskal-Wallis test for stochastic dominance among k groups in the software R, using the package dunn.test [62].

The Chi-square test computes whether two variables are independent or not. The test statistics are given by the following well-known formula [56]:

where Oi,j denotes the observed counts, Ei,j are expected counts that are computed as Ei,j = nicj/n, and cj are the column counts, i.e., the total number of observations in the jth class given by

The Mann–Whitney U test is a nonparametric equivalent of the independent samples t-test that we use because our variables do not have a normal distribution (verified using a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). U test statistics employ the smaller value of U1 and U2 that are computed as [63,64]

where n1(2) is the sample size from the sample set 1(2), and R1(2) is the sum of the ranks in the sample set 1(2).

The Kruskal–Wallis test compares the median of more than two populations to determine whether they are different [65]. This is a nonparametric alternative to one-way between-subjects ANOVA, in order to compute Kruskal–Wallis H test statistics, we use the formula given by [66]

where N is the number of values from all combined samples, Ri is the sum of the ranks from a particular sample, and ni is the number of values from the corresponding rank-sum.

Dunn’s [67] post hoc pairwise multiple comparisons are appropriate to follow the rejection of a Kruskal–Wallis test, using z-statistics for the groups, A and B, given by

where the input to the test is the per-group average rank , and the standard error is calculated as follows: , is the total sample size of the k groups, r is the number of tied ranks across all k groups, and τs is the number of observations across all k groups with the sth tied rank.

In the resulting Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12 and Table 13, *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Table 4.

Cross tabulation and Chi-square test (results of Hypothesis 1).

Table 5.

Mann–Whitney U test (results of Hypothesis 2).

Table 6.

Mann–Whitney U test (results of Hypothesis 2a).

Table 7.

Mann–Whitney U test (results of Hypothesis 2b).

Table 8.

Kruskal–Wallis test (results of Hypothesis 3).

Table 9.

Cross Tabulation and Chi-square test (results of hypothesis 3).

Table 10.

Kruskal–Wallis test (results of Hypothesis 4).

Table 11.

Cross Tabulation and Chi-square test (results of Hypothesis 4).

Table 12.

Kruskal–Wallis test (results of Hypothesis 5).

Table 13.

Cross Tabulation and Chi-square test (results of Hypothesis 5).

4. Results

According to Hypothesis 1, we assume that if a company has incorporated CSR, it also has EMS. To verify Hypothesis 1, we used a Chi-square test. Table 4 presents the results of this test via Cross Tabulation, specifically the absolute observed counts, and relative observed counts in brackets (in %). The results show that there exists a statistically significant relationship between incorporating CSR and incorporating EMS. In total, 61 (30.5%) companies have both CSR and EMS, 40 companies have only CSR, 28 has only EMS, and up to 71 (35.5%) companies include none of these systems in their organization. We can thus confirm Hypothesis 1.

In Hypothesis 2, we assumed that companies certified in both CSR and EMS will have higher profit than those that have only one of them. Therefore, the research sample consisted of only 129 companies because there is a requirement to have at least one certificate. As our dependent variable (profit) does not have a normal distribution (verified by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), we used a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. Table 5 presents the results, based on which we reject Hypothesis 2. There are no statistically significant differences in the company profits between the companies that have incorporated both CSR and EMS and those that have incorporated only one of them. The mean profit of companies that use both of these certificates is 7,829,120 euros; the mean profit of companies that use only one of them is 16,245,919 euros.

The partial Hypothesis 2a assumes that there exists a statistically significant difference in the profit between the companies that have incorporated CSR and those that have not. Next, we use the full research sample consisting of 200 companies, and to test the given hypothesis, we used the Mann–Whitney U test. The results (Table 6) confirm the statistically significant differences between the analyzed groups (Hypothesis 2a), but, interestingly, the companies with CSR achieved lower profits (the mean is 8,752,008 euros) than those without CSR (the mean is 27,552,822 euros).

The same analysis was performed within partial Hypothesis 2b, as we wanted to confirm the assumption that there exists a statistically significant difference in the profits between the companies that have incorporated EMS and those that have not. In this case, we reject Hypothesis 2b (see Table 7), as the use of EMS in a company does not influence the amount of profit.

As our research sample consists of companies from 12 various groups of industries (sectors) in the Slovak Republic, we assume that those in the selected sectors are CSR certified more often than those in the other sectors. From a statistical point of view, the alternative hypothesis of the Kruskal–Wallis test assumes that at least one population median of one group is different from the population median of at least one other group. The results (Table 8) confirm Hypothesis 3.

By using multiple comparisons of the mean ranks for all groups, we determined that there is a difference between the automotive industry and the service and business sector, i.e., the industries comprising 43% of our total sample of companies. This is confirmed by the results of the Dunn’s test, where the z-statistic for the pairwise comparisons between the mentioned two sectors is −3.7214 and the p-value is 0.0065. In the following Table 9, we show that the variables of industry (automotive /service and business) and incorporation of CSR are dependent. Cross tabulation shows that when considering the 41 companies from the service and business sector, 32 of them (78.05%) have incorporated CSR. On the other hand, in the automotive industry, more companies (28) have not incorporated CSR (62.22% of all 45 companies operate in the automotive industry).

Similarly, we verified Hypothesis 4, which assumes that some sectors are CSR certified more often than others. The Kruskal–Wallis test confirms this hypothesis (Table 10), while the multiple comparisons of the mean rank for all groups show that the main difference is again between the automotive industry and the service and business sector. Dunn’s test z-statistic for this pair of sectors is—4.7971 and the p-value is 0.0001. Cross tabulation (Table 11) records very similar results to those in Hypothesis 3. In total, 80.49% of companies from the service and business sector have incorporated EMS, but only 28.89% in the automotive industry has done the same.

Finally, using Hypothesis 5, we aimed to determine whether some sectors are both CSR and EMS certified more often than other sectors. The Kruskal–Wallis test (Table 12) shows, that by incorporating CSR and EMS concurrently, at least one population median of one industry is different from the population median of at least one other industry. Also, in this case, multiple comparisons of the mean rank for all groups show that this difference is between the automotive industry and the service and business sector. Specifically, the z-statistic for the pairwise comparisons between mentioned two sectors of the Dunn’s test is −5.5152 and the p-value is 0.0000.

Subsequently, we sought to confirm the presence of a statistically significant relationship between the type of industry (automotive/service and business) and the incorporation of CSR and EMS concurrently. The chi-square test (Table 13) confirms this assumption, and both systems are implemented in the service and business sector rather than in the automotive industry (68.29% from all service and business companies, and only 13.33% of all companies from the automotive industry).

Thus, incorporating CSR and EMS concurrently, and incorporating only EMS do not influence the volume of profits of a company. When a company incorporates only CSR, its profits are lower than when the company CSR does not use CSR. Moreover, we have shown that companies from the service and business sector include certified CSR, EMS, or both more often than companies from the automotive industry. Therefore, we confirm Hypotheses 1, 2a, 3–5.

5. Discussion

Sustainability ensures that companies do not primarily make short-term decisions but instead think in a longer timeframe and consider more factors than just the profit or loss involved. According to Štefko [68] long-term sustainability results from a company’s competitive position. Firms should set goals for sustainability and then aim to achieve them. Sustainability is becoming increasingly important for all companies in all industries. To achieve their sustainability goals, companies use different management tools, one of which is CSR incorporation. In 2002, global research on managers defined CSR as an important business issue that will become more important in the future [69]. According to another study (2013), CSR initiatives impact the total corporate efficiency more strongly through strategic CSR incorporation [70], and positive implementation of the CSR positively affects a company’s profits [71,72]. Based on this research [73], companies in the Slovak Republic are aware of the importance of their social responsibility. The most important motive for the fulfilment of CSR activities is a company’s own profit. CSR is more commonly implemented in developing and developed economies [74]. While the original focus of CSR was social, recent developments also incorporate environmental responsibility. Studies have proven that cooperation between these two domains can lead to higher efficiency in general management [68]. “Environmental CSR” has become an integral part of CSR and is a very important part of business culture [75]. The Polish Department of Standardized Management Systems conducted research between 1997 and 2004 on Polish companies certified according to ISO 14001. This system has identified two groups of benefits: internal ones and external ones [35]. Internal benefits include the following: reduction in costs and increased profitability. External benefits are related to an improved image and activities directed towards the external environment related to competitiveness. Through the years various benefits of EMS certification both for companies and for the environment have been examined. These benefits have resulted in the specification of multiple positive benefits or outcomes following ISO 14001 certification. On the contrary, other studies concluded that the certification process did not result in any significant changes in organizational performance or practices [76,77]. The French Standardization Association (AFNOR) introduced a study researched by the Paris Dauphine University entitled “Performance des organizations”. This study proves that environmental practices such as ISO 14001 EMS significantly influence a business’s economic performance [78]. The impacts of self-regulation and other CSR company practices on environmental practices are important but not fully understood—especially in transitional and developing countries [79]. In developing countries, “companies increasingly use management certification to overcome reputation problems and enter international markets” [80]. According to a study presented in 2011, managers of Western European companies are more inclined to engage in the implementation of environmental governance structures or processes [48,81]. Research produced by Slovak firms confirmed that certification in Standard ISO 140001 makes such companies more competitive in the market, both globally and locally [82]. Implementation of the environmental managerial systems in the conditions of the Slovak republic is often influenced by relationships with other organizations and business partners. Businesses that are the suppliers of foreign companies are often forced to implement a quality system, as well as an environmental managerial system [83].

There are also other positive effects resulting from the incorporation of social aspects and environmental awareness into corporate management [42,84]. Overall, 91–% of companies gained profits from their improved image and more intensive business relations through ISO 14001 certification [77,85,86,87]. Other effects are concerned with managers involvement, their roles and competencies [35,88,89,90], and human resources development through trainings and the dissemination of knowledge [77,91], as a very important issue in organizational theory and practice is obtaining the appropriate knowledge and sharing it within the company [92]. Further studies in this research field may investigate the impact of incorporating modern management tools, such as CSR and EMS, into human resources management.

6. Conclusions

Sustainability protects the environment and human and ecological health by driving innovation [3]. Organizational sustainability is defined as the cooperation between ecological tolerance, human resources development, and economic profitability [2]. The literature considers Environmental Management Systems (EMSs) such as ISO 14001, and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) to be factors that support organizational changes towards more sustainable production [93]. Recently, global trends have shown that most economically developed industries respect both environmental protection and social welfare as well as the economic value creation. Companies concentrate on an improvement of human life and welfare, as well as the effective use of the ecological resources, through the use of the financial resources needed to maintain the environmental protection and social welfare activities of the corporations [94]. These trends also detect new activities concerned with environmental and social responsibility [95,96].

The principal aim of this article was to determine whether the implementation of the CSR and certifying EMS (ISO 14001) (either externally or mutually) influence the economic results of the searched companies. The secondary objective was to observe the incorporation of these two management tools in various sectors of the national economy. Based on our aim, in this paper, we set five hypotheses. To verify the individual hypothesis, we used well-established methods, specifically a Pearson Chi-square test (Hypotheses 1,3–5), a Mann–Whitney U test (Hypothesis 2,2a,b), and a Kruskal–Wallis test (Hypotheses 3–5), alongside the Statistica software.

According to Hypothesis 1, we assumed that if a company incorporates CSR, it also features EMS. The results show that there exists a statistically significant relationship between incorporating CSR and incorporating EMS. Thus, we can confirm Hypothesis 1.

Many presented studies declare that implementation of management tools, such as CSR and EMS significantly influence companies’ economic behavior [3,78,79,94]. According to Hypothesis 2, we assumed that companies with both CSR and EMS will have higher profits than those that have only one of them. Table 5 presents the results, based on which we reject Hypothesis 2. There are no statistically significant differences in the profit between the companies that have incorporated both CSR and EMS, and those that have incorporated only one of them. The partial Hypothesis 2a assumes that there exists a statistically significant difference in the profits between the companies that have incorporated CSR and those that have not. The results (Table 6) confirm the presence of statistically significant differences between the analyzed groups. However, companies with CSR achieved lower profits than those without CSR. The same analysis was performed to test partial Hypothesis 2b, as we sought to confirm the assumption that there exists a statistically significant difference in the profits between the companies that have incorporated EMS and those that have not. In this case, we reject Hypothesis 2b (see Table 7). Therefore, the integration of EMS in a company does not influence the amount of profit.

As our research sample consists of companies from 12 various groups of industries (sectors) in the Slovak Republic, we assume that CSR is certified more often in the selected sectors than in other sectors. The results (Table 8) confirm Hypothesis 3. By using multiple comparisons of the mean rank for all groups, we determined that there is a difference between the automotive industry and the service and business sector (i.e., the industries), from which 43% of our total sample of companies is taken. In Table 9, we show that the variables of industry (automotive /service and business) and CSR incorporation are dependent.

Similarly, we verify Hypothesis 4, which assumes that some sectors are CSR certified more often than other sectors. The Kruskal–Wallis test confirms this Hypothesis (Table 10), while multiple comparisons of the mean rank for all groups show that the main difference is again between the automotive industry and the service and business sector.

Finally, testing Hypothesis 5, we aimed to determine whether some sectors are both CSR and EMS certified more often than other sectors. Table 12 shows, that, according to the incorporation of CSR and EMS concurrently, at least one population median of one industry is different from the population median of at least one other industry. Likewise, multiple comparisons of the mean rank for all groups show that main difference is between the automotive industry and the service and business sector.

Subsequently, we aimed to confirm the presence of a statistically significant relationship between the type of industry (automotive / service and business) and incorporating CSR and EMS concurrently. Table 13 confirms this assumption. Both systems are implemented in the service and business sector rather than in the automotive industry. In Slovakian corporate sustainability practices, the most active sectors are technology, telecommunications, and retail companies. These are mostly branches of foreign companies.

This work contributes to the literature on sustainability, corporate social behavior and environmental certification in firms operating in various sectors of the national economy.

However, this work also has its limitations. The research involves nonfinancial companies, and selected management tools, such as CSR behavior and EMS implementation. Accordingly, future studies may also examine financial companies and take into account other management tools for improving the social and environmental consciousness of companies which may lead to their sustainable development. One way of deepening the researched topic is observing the topic of total management quality, its linkage with CSR and EMS, and their common impact on company profit. Other way of improving the informative value of this research is to expand the territorial research scope of this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D. and R.K.; methodology, P.V.; software, P.V.; validation, P.V.; formal analysis, P.V.; investigation, P.V.; resources, M.D. and M.M.; data curation, P.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D., M.M. and R.K.; writing—review and editing, M.D. and R.K.; visualization, M.D. and P.V.; supervision, R.K.; project administration, M.D. and R.K.; funding acquisition, R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research, and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences, grant numbers VEGA 1/0578/18 and VEGA 1/0082/19; by the Cultural and Educational Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic, grant numbers KEGA 011PU-4/2019 and KEGA 024PU-4/2020.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the journal editor and anonymous reviewers for their guidance and constructive suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kim, J.; Kim, J. Corporate Sustainability Management and Its Market Benefits. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herghiligiu, I.V.; Robu, I.B.; Pislaru, M.; Vilcu, A.; Asandului, A.L.; Avasilcai, S.; Balan, C. Sustainable Environmenatl Management System Integration and Business Performance: A Balance Assesment Approach Using Fuzzy Logic. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, T.S.; Lee, A.S.; Teh, B.H.; Magsi, H.B. Environmental Innovation, Environmental Performance and Financial Performance: Evidence from Malaysian Environmental Proactive Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Available online: https://www.unido.org/our-focus/advancing-economic-competitiveness/competitive-trade-capacities-and-corporate-responsibility/corporate-social-responsibility-market-integration/what-csr (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Slavić, A.; Berber, N. The Role of HRM in CSR and Sustainable Development: Findings from V4 and Serbia. In Corporate Social Responsibility and Human Resources Management, Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Nitra, Slovakia, 4–5 June 2015; Ubrežiová, I., Lančarič, D., Košičiarová, I., Eds.; SPU: Nitra, Slovakia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, Y. The Effects of Corporate Green Efforts for Sustainability: An Event Study Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgemci, T.; Doganalp, B.; Cagliyan, V. Eco-productivity as the sustainable competitive advantage source: An analysis of recent application from Turkish enterprises. In International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM), Proceedings of the 10th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2010, Albena, Bulgaria, 20–26 June 2010; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 537–544. [Google Scholar]

- Florida, R.; Davison, D. Gaining from green management. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornoglio, C.; Botta, S. The use of indicators and the role of Environmental Management Systems for environmental performances improvement: A survey on ISO 14001 certified companies in the automotive sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.; Yakovleva, N. Corporate social responsibility in the mining industry: Exploring trends in social and environmental disclosure. J. Clean. Prod. 2006, 14, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Partnerships from cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st-century business. Environ. Qual. Manag. 1998, 8, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.B.; Hail, L.; Leuz, C. Adoption of CSR and Sustainability Reporting Standards: Economic Analysis and Review; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komodromos, M.; Melanthiou, Y. Corporate Reputation through Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Insights from Service Industry Companies. J. Promot. Manag. 2014, 20, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. In Corporate Ethics and Corporate Governance; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Labour. Social Affairs and Family of the Slovak Republic. Available online: https://www.employment.gov.sk/sk/ministerstvo/spolocenska-zodpovednost/ (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Amor-Esteban, V.; Galindo-Villardón, M.P.; David, F. Study of the Importance of National Identity in the Development of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices: A Multivariate Vision. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguedas, C.; Blanco, E. On Fraud and Certification of Corporate Social Responsibility. Working Papers in Economics and Statistics 2014–2018. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/101083 (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Freeman, R. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman/Ballinger: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental stakeholder theory: A synthesis of ethics and economics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 404–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Ethical Challenges for Business in the New Millennium: Corporate Social Responsibility and Models of Management Morality. Bus. Ethics Q. 2000, 10, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.H.; Liang, W.C. Exploring the Determinants of Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: An Empirical Examination. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, G.P. The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 595–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, E.H.; Haire, M. A strategic posture toward corporate social responsibility. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1975, 18, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brin, P.; Nehme, M.N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Analysis of Theories and Models. EUREKA Soc. Humanit. 2019, 5, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geva, A. Three models of corporate social responsibility: Interrelationships between theory, research, and practice. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2008, 113, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.; Bergmans, F. Learning about Corporate Social Responsibility: The Dutch Experience; IOS press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, M. Innovations in Corporate Social Responsibility from Global Business Leaders at Panasonic, Thomson Reuters and Nanyang Business School. Am. J. Econ. Bus. Adm. 2010, 2, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajnoha, R.; Lesnikova, P.; Stefko, R.; Schmidtova, J.; Formanek, I. Transformation in strategic business planning in the context of sustainability and business goals setting. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2019, 18, 44–66. [Google Scholar]

- European Comission. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/emas/about/index_en.htm (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Fazekašová, D.; Fazekaš, J.; Chovancová, J.; Rovňák, M.; Torma, S.; Vavrek, R. Prírodné Zdroje a ich Využitie v Podmienkach Udržateľného Rozvoj; Bookman: Prešov, Slovakia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chereminisoff, N.P.; Bendavid-Val, A. Green Profits: The Manager’s Handbook for ISO 14001 and Pollution Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralikrishna, I.V.; Manickam, V. Environmental Management: Science and Engineering for Industry; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 177–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, D.; Rondinelli, D. Adopting Corporate Environmental Management Systems: Motivations and Results of ISO 14001and EMAS Certification. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Magazine. Available online: http://www.enviromagazin.sk/enviromc1_3/systemy14.html (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Sakal, P. Environmental Business Strategy; Slovak University of Technology: Trnava, Slovakia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pesce, M.; Shi, C.; Critto, A.; Wang, X.; Marcomini, A. SWOT Analysis of the Application of International Standard ISO 14001 in the Chinese Context. A Case Study of Guangdong Province. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplicka, K.; Culkova, K.; Antosova, M. Advantages and disadvantages of Environmental Management System and emas for mining corporations. In SGEM2013 Conference Proceedings, Proceedings of the 13th SGEM GeoConference on Ecology, Economics, Education and Legislation, Albena, Bulgaria, 16–22 June 2013; STEF92: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Slovak Environmental Agency. Available online: http://www.sazp.sk/public/index/go.php?id=1723 (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pontrandolfo, P. Being ‘Green and Competitive’: The Impact of Environmental Actions and Collaborations on Firm Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxin, M.F.; Knuteson, S.L.; Bartholomew, A. Outcomes and Key Factors of Success for ISO 14001 Certification: Evidence from an Emerging Arab Gulf Country. Sustainability 2020, 12, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Searcy, C.; Zutshi, A.; Fisscher, O.A. An integrated management systems approach to corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 56, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Toffel, M.W. Stakeholders and Environmental Management Practices: An Institutional Framework. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2004, 12, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R.; Langer, M.E.; Konrad, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, Stakeholders and Sustainable Development I: A Theoretical Exploration of Business—Society Relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.; Rondinelli, D. Proactive corporate management: Environmental new industrial revolution. Acad. Manag. Exec. 1998, 12, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, S.; Stern, N. Why economic analysis supports strong action on climate change: A response to the Stern Review’s critics. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2008, 2, 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlitzky, M.; Siegel, D.S.; Waldman, D.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Sustainability. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSegni, D.M.; Huly, M.; Akron, S. Corporate social responsibility, environmental leadership and financial performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafilova, S.; Babiak, K.; Heinze, K. Corporate social responsibility and environmental sustainability: Why professional sport is greening the playing field. Sport Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 298–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baughn, C.C.; Bodie, N.L.; McIntosh, J.C. Corporate social and environmental responsibility in Asian countries and other geographical regions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2007, 14, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Khalili, N.R.; Cheng, W. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in China: Trends, Context, and Impact on Company Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.L.; Ho, J.A.; Sambasivan, M. Impact of Corporate Political Activity on the Relationship Between Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance: A Dynamic Panel Data Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, L. Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (KPMG). The KPMG Survey of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting; KPMG: London, UK, 2011; Available online: https://www.kpmg.de/docs/Survey-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2011.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Daszynska-Zygadlo, K.; Slonski, T.; Zawadzki, B. The market value of CSR performance across sectors. Eng. Econ. 2016, 27, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, G.M. Corporate Social Responsibility—An Economic and Financial Framework. Geneva Pap. Risk Insur.-Issues Pract. 2004, 30, 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenčová, S. Aplikácia Pokročilých Metód vo Finančno-Ekonomickej Analýze Elektrotechnického Odvetvia Slovenskej Republiky; VŠB-TU: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FinStat. Available online: https://finstat.sk/databaza-financnych-udajov (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Privitera, G.J. Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- De Sá, J.P.M. Applied Statistics: Using SPSS, STATISTICA, and MATLAB; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dinno, A. Dunn’s Test. of Multiple Comparisons Using Rank Sums. 2017. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dunn.test/dunn.test.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Martínez-Murcia, F.J.; Górriz, J.M.; Ramirez, J.; Puntonet, C.G.; Salas-Gonzalez, D. Computer Aided Diagnosis Toll for Alzheimer´s Disease based on Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon U-Test. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 9676–9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Košíková, M.; Loumová, V.; Kovaľová, J.; Vašaničová, P.; Bondarenko, V.M. A Cross-Culture Study of Academic Procrastination and Using Effective Time Management. Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, D. Intermediate Statistics for Dummies; Wiley Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Corder, G.W.; Foreman, D.I. Nonparametric Statistics for Non-Statisticians; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, O.J. Multiple Comparisons among Means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1961, 56, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štefko, R. Personálna Práca v Hyperkonkurenčnom Prostredí a Personálny Marketing; R.S. Royal Service: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel, I. Corporate social responsibility and corporate sustainability: Separate pasts, common futures. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Boesso, G.; Kumar, K. Examining the Link between Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility and Company Performance: An Analysis of the Best Corporate Citizens. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planer-Friedrich, L.; Sahm, M. Strategic corporate social responsibility, imperfect competition, and market concentration. J. Econ. 2020, 129, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, L.; Buccella, D. Pareto-Superiority of Corporate Social Responsibility in Unionised Industries. Arthaniti J. Econ. Theory Pr. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubreziova, I.; Stankovič, L.; Mihalčová, B.; Ubrežiová, A. Perception of Corporate Social Responsibility in companies of Eastern Slovakia region in 2009 and 2010. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2013, 61, 2903–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.N. Making sense of the black box: An empirical analysis investigating strategic cognition of CSR strategists in a transitional market. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 916–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, C.M.G.; Aguiar, A.D.O.E. ISO 14001 and international trade. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2019, 10, 022–040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Tene, C.V.T. Adoption and Outcomes of ISO 14001: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaute-Samanni, L.; Grevêche, M.P. Au Coeur de l’ISO 14001:2015: Le Système de Management Environnemental au Centre de la Stratégie; AFNOR: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mijatovic, I.; Maricic, M.; Horvat, A. The Factors Affecting the Environmental Practises of Companies: The Case of Serbia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, K.; Mangelsdorf, A.; Pohlisch, J. The Effects of Cooperation in Accreditation on International Trade: Empirical Evidence on ISO 9000 Certifications. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 798, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, C.; Rahman, N.; Rubow, E. Green Governance: Boards of Directors’ Composition and Environmental Corporate Social Responsibility. Bus. Soc. 2011, 50, 189–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre of Society, Economy and Ecology. Available online: http://www.ekologika.sk/environmentalne-manazerstvo.html (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Dubravská, M.; Kotulič, R. Benefits of Environmental Management Systems Implementation in the conditions of the Slovak Republic. In International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConferences (SGEM), Proceedings of the 14th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM 2014, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Musová, Z. Responsible behavior of businesses and its impact on consumer behavior. Acta Oeconomica Univ. Selye 2015, 4, 138–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sambasivan, M.; Fei, N.Y. Evaluation of critical success factors of implementation of ISO 14001 using analytic hierarchy process AHP: A case study from Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1424–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, A.M. ISO 14000 Environmental Management System in construction: An examination of its application in Turkey. Total Qual. Manag. 2009, 20, 713–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poksinska, B.; Dahlgaard, J.J.; Eklund, J.A. Implementing ISO 14000 in Sweden: Motives, benefits and comparisons with ISO 9000. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2003, 20, 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, S.; Naveh, E. Standardization and discretion: Does the environmental standard ISO 14001 lead to performance benefits? IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 53, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.A.; Hens, L. Environmental performance of the cement industry in Vietnam: The influence of ISO 14001 certification. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 96, 362–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondinelli, D.; Vastag, G. Panacea, common sense, or just a label? The value of ISO 14001 environmental management systems. Eur. Manag. J. 2000, 18, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M. Organizational consequences of implementing an ISO 14001 Environmental Management System an empirical analysis. Organ. Environ. 2007, 20, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencsik, A.; Juhász, T.; Mura, L.; Csanádi, Á. Formal and Informal Knowledge Sharing in Organisations from Slovakia and Hungary. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2019, 7, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labella, R.C.; Fort, F.; Parras-Rosa, M. Motives, Barriers and Expected Benefits of ISO 14001 in the Agri-food sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.W. Corporate social responsibility in China: Window dressing or structural change. Berkeley J. Int. Law 2010, 28, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental projecting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Projecting Initiative (GRI). Sustainability Projecting Guidelines; GRI: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).