The Importance of Spiritual Values in the Process of Managerial Decision-Making in the Enterprise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

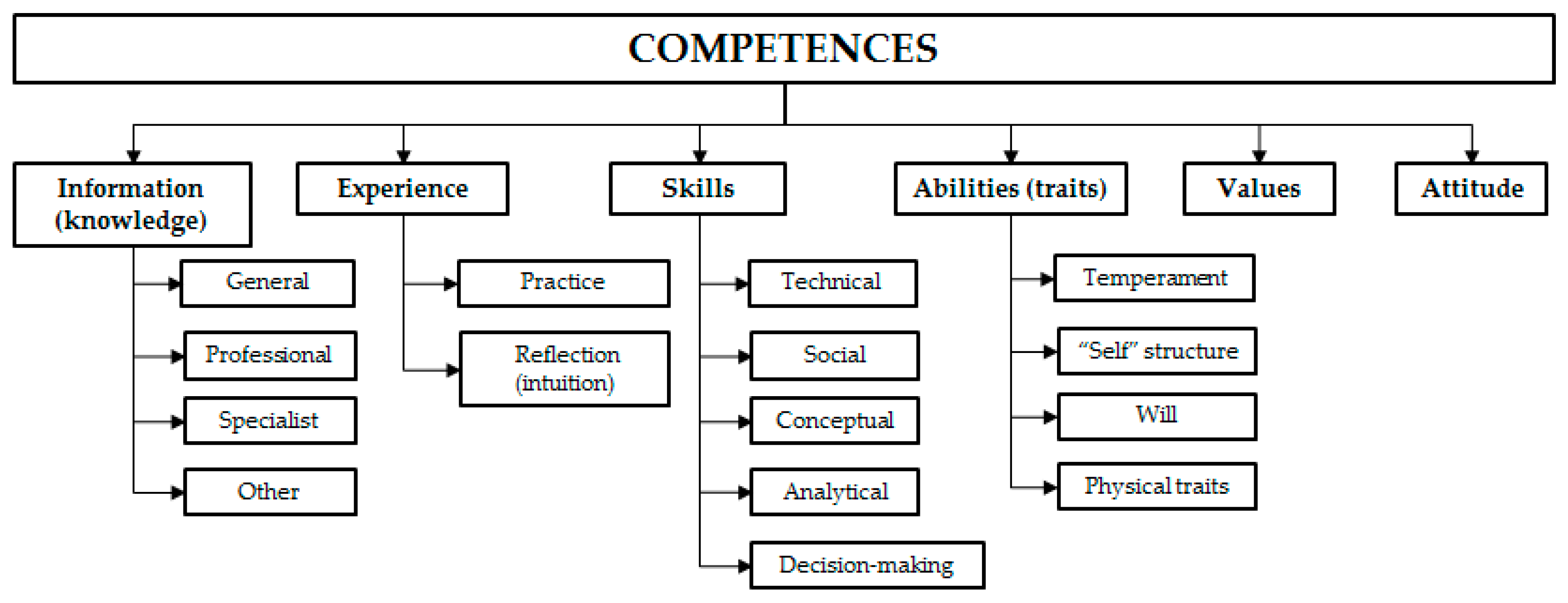

2.1. Manager and Their Competences

2.2. Christian Values Upheld by the Managers

- supernatural phenomena, articles of faith, rationally unverifiable;

- revealed truths, referring to a human and their life being of anthropological and ethical nature;

- Christian beliefs and their role in a human life, culture, and history of mankind.

- spirituality improves well-being of the employees and the quality of life,

- spirituality ensures that the employees have the sense of purpose at work,

- spirituality ensures that the employees have the sense of connection and community.

3. Materials and Methods

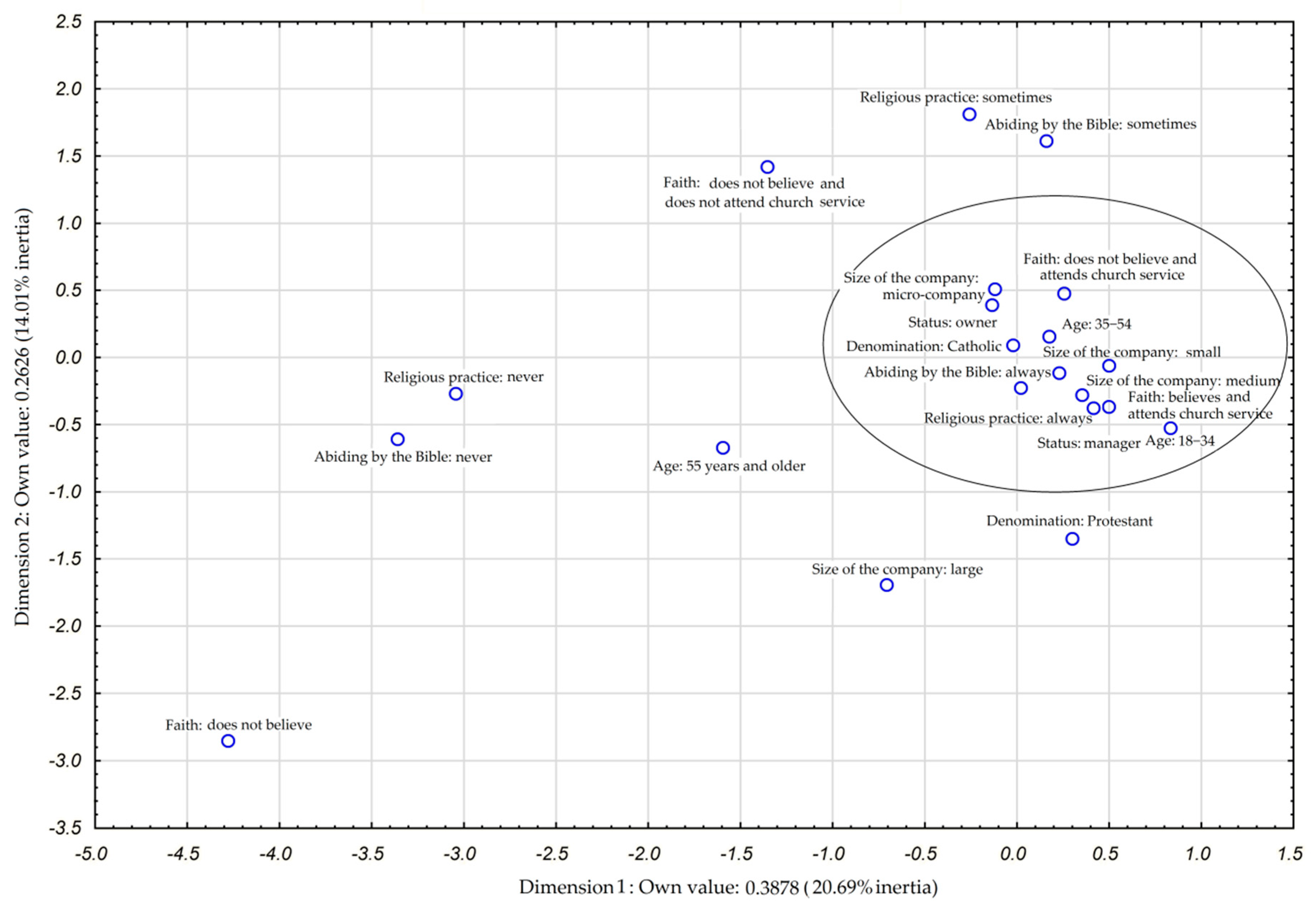

4. Results of Own Research

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griffin, R.W. Management, 11th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stoner, J.A.; Freeman, R.E. Management, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, F.W. Scientific Management; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1911. [Google Scholar]

- Załoga, W. Model kompetencji menedżera w nowoczesnej organizacji. Zesz. Nauk. UPH Siedlcach 2013, 97, 453. [Google Scholar]

- Fayol, H. General and Industrial Management; Pitman: London, UK, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H. The Nature of Managerial Work; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Kotter, J.P. The General Menagers; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, C. Does It Matter What Managers Do? Bus. Strategy Rev. 2001, 12, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urlich, D. Liderzy Zarządzania Zasobami Ludzkimi. Nowe Wyzwania. Nowe Role; Oficyna Ekonomiczna: Kraków, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, R.E. Beyond Rational Management: Mastering Paradoxes and Competing Demands of High Effectiveness; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Kieżun, W. Sprawne Zarządzanie Organizacją; SGH: Warszawa, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, R.A. Management: Basic Elements of Managing Organizations; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bendkowski, J.; Bendkowski, J. Praktyczne Zarządzanie Organizacjami. Kompetencje Menedżerskie; Wyd. Politechniki Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Avery, G.C. Understanding Leadership: Paradigms and Cases; Sage: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- New, G.E. Reflections A three-tier model of organizational competencies. J. Manag. Psychol. 1996, 11, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosal, C.Z. Psychologia Decyzji Kadrowych; Wyd. Profesjonalnej Szkoły Biznesu: Kraków, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chmiel, N. Psychologia Pracy i Organizacji; Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne: Gdańsk, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R. Competent Manager; John Wiley and Son: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham, G.; Chivers, G. The reflective (and competent) practitioner: A model of professional competence which seeks to harmonize the reflective practitioner and competence-based approaches. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1998, 22, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruffe, C. What is meant by competency? In Designing and Achieving Competency; Boam, R., Sparrow, P., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Egeman, M. Przedmowa do polskiego wydania. In Zatrudnienie i Kompetencje w Przedsiębiorstwach Procesach Zmian; Thierry, D., Sauret, C., Monod, N., Eds.; Poltext: Warszawa, Poland, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- BTEC. National Vocational Qualification at level 5 in Management, Part 2: Standards BTEC Publications. Hum. Perform. 1990, 6, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, T. The meanings of competency. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 1999, 23, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pocztowski, A. Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi. Koncepcje—Praktyki—Wyzwania; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sajkiewicz, A. Kompetencje Menedżerów w Organizacji Uczącej Się; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo, L. Global Christianity—A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Christian Population. Relig. Public Life 2011, 12, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bible. Biblia Tysiąclecia; Pallottinum: Poznań, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zwoliński, A. Wychowawca. Miesięcznik Naucz. Wychowawców Katol. 1998, 4, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Szromek, A.R. Zarządzanie Ewangeliczne; DEHON: Kraków, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sirico, R.A. Religia, Wolność, Przedsiębiorczość (Eseje Wybrane); Wydanie, I., Arwil, S.C., Eds.; The Acton Institute for the Study of Religion and Liberty: Warszawa, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sirico, R.A. The Entrepreneurial Vocation. J. Mark. Moral. 2000, 3, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelands, L.E. The Real Mystery of Positive Business: A Response from Christian Faith. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 771–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conroy, S.J.; Emerson, T.L. Business ethics and religion: Religiosity as a predictor of ethical awareness among students. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, M. Spirituality Incorporated: Including Convergent Spiritual Values in Business. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 132, 779–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porras, C.V.; Toro-Jaramillo, I.D. Spirituality and Organizations: A Proposal for a New Company Style Based on a Systematic Review of Literature. Religions 2020, 11, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J. Spirituality in management education. J. Manag. Educ. 1997, 21, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freshman, B. An exploratory analysis of definitions and applications of spirituality in the workplace. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1999, 12, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodinsky, R.W.; Giacalone, R.A.; Jurkiewicz, C.L. Workplace values and outcomes: Exploring personal, organizational, and interactive workplace spirituality. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumpikaitė-Valiūnienė, V. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences. Econ. Bus. 2014, 150, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.; Williams, P. Faith and Work: Christian Perspectives, Research and Insights into the Movement; Ewest, T., Ed.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tischler, L.; Biberman, J.; McKeage, R. Linking emotional intelligence, spirituality and workplace performance: Definitions, models and ideas for research. J. Manag. Psychol. 2002, 17, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corner, P.D. Workplace Spirituality and Business Ethics: Insights from an Eastern Spiritual Tradition. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metters, R. The Effect of Employee and Customer Religious Beliefs on Business Operating Decisions. Religions 2019, 10, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brügger, T.; Huppenbauer, M. The Study of Christians at Work. Acad. Manag. Annu. Meet. Proc. 2019, 1, 10879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, M.L.; Naughton, M.J.; VanderVeen, S. Connecting religion and work: Patterns and influences of work-faith integration. Hum. Relat. 2011, 64, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.W.; Ewest, T.; Neubert, M.J. Development of The Integration Profile (TIP) Faith and Work Integration Scale. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, B.; Schroeder, D. Management, Theology and Moral Points of View: Towards an Alternative to the Conventional Materialist-Individualist Ideal-Type of Management. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 705–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, B.; Wiebe, E. Salvation, theology and organizational practices across the centuries. Organization 2012, 19, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buszka, S.G.; Ewest, T. Integrating Christian Faith and Work: Individual, Occupational, and Organizational Influences and Strategies; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.W.; Ewest, T. A new framework for analyzing organizational workplace religion and spirituality. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2015, 12, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakas, F. Spirituality and Performance in Organizations: A Literature Review. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, A.A.; Gibbs, M. The Ten Commandments Perspective Power and Authority in Organizations. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 26, 351–361. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, M.; Conroy, M.; Blakeley, K.; de Marco, S. Having Burned the Straw Man of Christian Spiritual Leadership, what can We Learn from Jesus about Leading Ethically? J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 757–769. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.; Kotler, P. Corporate Social Responsibility Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; Hoboken Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy, B. Defining CSR: Problems and Solutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Jo, H.; Velasquez, M.G. Community Religion, Employees, and the Social License to Operate. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 775–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourish, D.; Tourish, N. Spirituality at work and its implications for leadership and followership. Leadership 2010, 5, 207–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.; Wiebe, E. Technical spirituality at work: Jacques Ellul on workplace spirituality. J. Manag. Inq. 2007, 16, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotsis, G.; Kortezi, Z. Philosophical Foundations of Workplace Spirituality: A Critical Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 78, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, G.W. The relationship between the integration of faith and work with life and job outcomes. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office of Poland. Życie Religijne w Polsce. Wyniki Badania Spójności Społecznej; GUS: Warszawa, Poland, 2018.

- Stanisz, A. Biostatystyka; Wyd. Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre, M.; Hastie, T. The Geometric Interpretation of Correspondence Analysis. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1987, 82, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Multivariete Analysis; Charles Griffin: London, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

| Conduct in Line with the Values Towards: | In General (xAv ± SD) | Groups (xAv ± SD) | p (A vs. B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | |||

| employees | 1.23 ± 0.97 | 1.29 ± 0.94 | 1.07 ± 1.07 | 0.411 |

| customers | 1.30 ± 0.78 | 1.39 ± 0.66 | 1.07 ± 1.00 | 0.293 |

| tax administration | 1.23 ± 0.84 | 1.39 ± 0.66 | 0.86 ± 1.10 | 0.094 |

| natural environment | 1.04 ± 0.81 | 1.09 ± 0.72 | 0.93 ± 1.00 | 0.760 |

| competition | 1.11 ± 0.81 | 1.12 ± 0.86 | 1.07 ± 0.73 | 0.687 |

| local community | 1.11 ± 0.91 | 1.24 ± 0.75 | 0.79 ± 1.19 | 0.235 |

| In general | 1.17 ± 0.85 | 1.25 ± 0.77 | 0.97 ± 1.02 | 0.022 |

| Promoting Christian Values by Managers Among: | In General (xAv ± SD) | Groups (xAv ± SD) | p (A vs. B) | ∆ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | ||||

| customers | 0.01 ± 1.38 | 0.12 ± 1.37 | −0.29 ± 1.44 | 0.379 | +0.41 |

| recipients and contractors | 0.29 ± 1.27 | 0.51 ± 1.16 | −0.21 ± 1.42 | 0.096 | +0.72 |

| employees | 0.52 ± 1.24 | 0.85 ± 1.05 | −0.29 ± 1.33 | 0.007 | +1.14 |

| In general | 0.27 ± 1.30 | 0.49 ± 1.19 | −0.26 ± 1.40 | 0.002 | +0.75 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szromek, A.R. The Importance of Spiritual Values in the Process of Managerial Decision-Making in the Enterprise. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135423

Szromek AR. The Importance of Spiritual Values in the Process of Managerial Decision-Making in the Enterprise. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135423

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzromek, Adam R. 2020. "The Importance of Spiritual Values in the Process of Managerial Decision-Making in the Enterprise" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135423

APA StyleSzromek, A. R. (2020). The Importance of Spiritual Values in the Process of Managerial Decision-Making in the Enterprise. Sustainability, 12(13), 5423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135423