1. Introduction

In spite of the considerable investments into the regional development in the Slovak Republic, the regional disparities have continuously increased since 1990s, and belong to the largest among the OECD countries [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Since the establishment of the Slovak Republic in 1993, the elimination of negative regional differences was declared as the key challenge by national governments; however, economic and social development of peripheral regions in the south-eastern and eastern part of the country is considerably slower than in the west, especially in comparison with the metropolitan region of Bratislava as the capital city.

Due to implementing different sectoral policies and programs aimed at improving the situation and strengthening regional economies, the development in the peripheral regions has been restarted; however, the efficiency of the proposed solutions was diminished by the lack of coordination and wider integration of sectoral policies under the umbrella of the national regional policy. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the government policy was focused on searching for strategic foreign investments and channelizing them to peripheral regions. This strategy was only partially successful as the majority of investors preferred well-connected and centrally located regions instead of the peripheral ones. In addition to this, these investments were shown to be a rather temporary solution due to their short-term character since the investors moved their factories to the countries with cheaper labor after several years. Another feature of the Slovak economy is the specialization in automobile manufacturing. It means 250,000 people are directly and indirectly employed by the automotive industry, which accounts for a 44% share of Slovakia’s total industrial production, with forecasts of 249 produced cars per 1000 inhabitants by 2020 [

5]. The global economic crisis at the end of 2000s caused diminishing of foreign investments which was reflected in slowing of the economy, especially in these regions.

This paper is focused on analyzing the regional development policies since 2015, when the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. on the support of lagging districts was enacted and a new approach aimed at strengthening the condition of the economies in these districts was introduced. In 2015, a new law on the support of lagging districts in Slovakia was introduced, which formulated a new framework that shifted the paradigm to how the development of these regions should be fostered. Within the Slovak administration structure, a regional level is represented by eight self-governing regions defined at the level of statistical unit Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) 3. These eight regions consist of 86 districts at the supra-municipal level corresponding to the Local Administrative Unit (LAU1). They are not recognized at the level of territorial government, but the practice of regional development has shown their importance as a part of hierarchic territorial multilevel polycentric governance structure addressing the diversity of self-governing regions by way of adequate place- and evidence-based strategies and actions.

This paper studies the applied strategies as tools framed by the new paradigm in the law on the support of lagging districts. The research question is to what extent do these tools, defined by this new law, represent the paradigm shift? The paper examines the nature of the applied strategies and plans and discusses their implementation results as of 2015.

After more than 4 years since the first action plan’s implementation, the first results can be evaluated and reviewed, and furthermore, the positive experience from this innovative approach can be implemented into the regional development policies across all levels. The evaluation of its effectiveness is based on the available unemployment data, increased number of newly-created jobs, labor productivity data by OECD, and qualitative data collected within the VEGA project supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Republic, within which the collection of qualitative data in the form of interviews with experts and key stakeholders was performed.

The first part of the paper reviews the regional development policies in Slovakia. The second part describes and analyzes the legislature related to regional development in Slovakia, framing new approaches introduced by Act no. 336/2015 Coll. The third part discusses the legal environment regarding the regional development in Slovakia. The fourth part presents the research methodology, the fifth part discusses the principles on which the action plans for lagging districts were built and the new tools for supporting regional development that this approach brings. In the sixth part we present and assess the effects of the newly introduced tools supporting, as parts of the action plans, the development of lagging districts in Slovakia. Lastly, we discuss the results and challenges of implementing these tools since 2015 and the perspectives for future development.

2. Regional Development and Cohesion Policy in Slovakia

The economy of the Slovak Republic underwent a multidimensional transformation with crucial change from centrally-planned to market-oriented economy after 1990s [

6]. Slovak regions experiencing these transformation processes were differently affected as their starting positions regarding the economic structure, location and infrastructure as the bases for their ability to respond to the new trends were rather different [

7]. Interregional disparities linked to natural preconditions and historic development have been deepened by ongoing structural changes in the economy, transition towards an open market mechanism in combination with the underdeveloped transport and technical infrastructures and lack of proper regional development policies [

6].

After more than two decades of top-down regional development policies, with the government pouring money into the regions and directing investments eastwards, the regional disparities were larger and it was clear that these policies did not deliver the expected impacts. It was essential that a dramatic shift occurred, not only based on re-directed funding, but also on creating low-added-value workplaces. It was recognized that social and economic development that capitalized on local and regional territorial capital, including the increase in availability of work opportunities based on specific available local human workforce would be necessary. This presupposes the turn from top-down to bottom-up approach in order to foster identification and efficient use of territorial capital of the regions in accordance with the OECD recommendations [

1].

Upon this premise, the Parliament of the Slovak Republic passed the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. on the support of lagging districts in 2015, aimed at improving the status quo of lagging districts in Slovakia. The law was based on the support of targeted activities sustaining the creation of new jobs and it was based on a premise to create conditions so that the development of these regions could be facilitated bottom-up [

8]. These activities should be coordinated in accordance with the action plans targeted at lessening the regional disparities by creating specific action-oriented plans [

9] launching the bottom-up development of these districts. These action plans were prepared by local stakeholders in cooperation with a group of experts representing different disciplines. This Act is an expression of specific pragmatic policy aiming at initializing the regional development, although, to a large extend, introducing this Act was not a systematic step as it does exist in parallel with the law on regional development.

Until today, 20 action plans have been prepared under the designation of ‘lagging district’ in accordance with the Act no. 335/2015. These include 12 pilot action plans prepared and approved by the government until 2016 which used the funding schemes based on the national funding and EU structural funds.

Cohesion Policy in Slovakia

Slovakia has been a member of the European Union since 2004 and even before the accession to the EU, it was eligible for pre-accession funding (e.g., PHARE projects). Before 2004, the country’s economy was based on foreign direct investment (FDI) and the adoption of existing technology [

3]. The objective of the EU Cohesion policy was to decrease the gap in productivity and welfare and to foster growth in a way that also supports territorial cohesion between regions [

10]. There are, however, several studies supporting the claim that the cohesion policy in Central and Eastern Europe did not improve the territorial cohesion and sometimes led to more persistent regional disparities [

11,

12]. According to many studies, the EU Cohesion policy is helping to converge the Central and Eastern European countries [

13,

14,

15], but this is mostly taking place on a cross-country level and, at the same time, the regional disparities within the countries are becoming greater. Michalek and Madajova [

16] add that the division of financial support did not fully follow the real needs of the problematic regions and often ignored significant internal differentiation and concentration within these regions. This situation resulted in deepened and aggravated disparities at the level of local administrative unit (LAU) 1 (NUTS 4 administrative districts).

All lagging regions are located in the eastern part of Slovakia. Many of these areas are rich in natural resources and in the past there used to be various factories and state-led businesses capitalizing on these natural and human resources (frequently as a result of post-WWII industrialization). However, the Velvet revolution in 1989 led to economic transformation of these regions from the state-led to market economy and liberalization. In many of these areas it was unregulated and led to privatization and ineffective management decisions, often supported by the state. Additionally, these areas today have a high share of the unqualified population (including the Roma population). Natural resources are often exploited inefficiently (e.g., raw materials such as wood and minerals being extracted and sold abroad where it is processed into products with higher added value). Moreover, large parts of these regions are agricultural and forest areas which often become attractive for acquiring EU subsidies, limiting the willingness of owners to capitalize on them by striving for economy with a higher added value.

Slovakia, like other Central European countries, is heavily dependent on cohesion policy interventions [

17]. The country is characterized by large territorial disparities (among the highest in the EU) in economic and social terms [

1,

3,

16,

18]. FDI in the past was mainly located in the western part of the country (Bratislava received 70% of the FDI between 1990 and 2013). This led to large core-periphery division reinforced in Slovakia in terms of private and public research and innovation and institutional capacities – Bratislava’s GDP is 2.4 times higher than the average of Slovakia and it is generating 53% of national research capacities [

3]. According to the study by Darvas et al. [

19], the best performing NUTS-2 region in Slovakia in terms of unexplained economic growth is the region of Bratislava and the worst performer is the region of Eastern Slovakia. Additionally, the cohesion policy in Slovakia is overseen very closely by the national government. This often places an unnecessary burden on sub-national administrations and beneficiaries, as a result of the heavily centralized approach in formulating and implementing the cohesion policy.

Schulz [

3] summarizes the economy of peripheral regions as suffering from poor public (higher education institutions etc.) and private (lacking critical mass of enterprises) research and innovation infrastructure and the fact that peripheral institutions severely lack capacities and are playing a minor role in formulation of development strategies. Other setbacks in these regions include the lack of expert and institutional capacities, poor absorption capacity of potential recipients and complicated project administration [

16]. This lack of softer investments in the cohesion policy priorities, with its increased focus on innovation policy, led Loewen and Schulz [

17] to proposing a separation of innovation and cohesion policies so that the cohesion policy could remain focused on the traditional domains such as infrastructure and social investments in underdeveloped regions, and therefore reflect the needs of Central European countries and its peripheral regions more accurately.

3. Regional Development Related Legislature

In this section, we review the legislature dealing with the regional development in Slovakia. The Act no. 539/2008 Coll. on supporting the regional development in the Slovak Republic as amended [

20] is compared with the second legal act, which is the Act no. 336 on the support of lagging districts [

21]. This Act is a new tool, which forms the basis of the shift in the regional policy from sectoral to integrative approaches. We highlight the differences in these legal acts and underline the proposed paradigm shift.

3.1. The Act No. 539/2008 Coll. As Amended

Regional development policies have been regulated since 2008 by the Act no. 539/2008 Coll. On supporting the regional development as amended. It is the basic legal act defining the objectives and preconditions for regional development and the structure of legal bodies on the national, regional and local level coordinating the regional development. This act describes regional development as a set of social, economic, cultural and environmental processes and relations taking place within the region and contributing to the increase in its competitiveness, sustainable growth, social and territorial development, and to the balance in the differences among the regions (§2). In accordance with this Act, the objective of the regional policy is to remove or decrease the undesired differences in the level of regional development, to increase the economic performance and competitiveness of the regions and development of innovations while ensuring sustainable development, and to increase the employment rate and quality of life of people in the regions (§3).

The funding of the regional policy includes resources from the national budget (including the funding from the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic for Investments and Informatization), resources of regional and municipal self-governments and other funding from natural and legal persons, corporate bodies and international organizations. EU Structural funds are defined as additional sources of funding (§4). The key documents of regional development management include the National Strategy of the Regional Development, the Development Programs of Social and Economic Development of Regions, the Programs of Social and Economic Development of Municipalities, and the Common Programs of Social and Economic Development of Municipalities (in case several municipalities prepare one common development program) (§5). The Act additionally defines the basic structure of the above listed programming documents.

This Act does not differentiate between the types of regions, i.e., the tools are the same for the dynamically developing regions, central and peripheral regions, lagging or developed regions. It creates the basic framework for regional policies without taking regional specifics and requirements into the consideration. This fact was the motivation to elaborate a new law specifically addressing these differences. Additionally, in accordance with this law, local economic advocates are not advocates relevant to the regional development and territorial strategies.

3.2. The Act No. 336/2015 Coll. As Amended

In this context, the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. On the Support of the Lagging Districts as amended was enacted. This act was also created in response to the emergence of anti-system and anti-democratic political parties and their rising popularity among the population, particularly in lagging districts, supporting these insurgent groups as a form of protest and appeal to the politicians. An urgent need to react to this situation promptly was the motivation to adopt the law.

We need to underline that this act represents a non-systematic measure being created in duplicity to the valid legal norm. It was a pragmatic step taken by the national government as the whole process of formulating a new set of laws changing the system of the state support for regional development would take a long time (months to years) and the demand for a strengthened and more effective approach to regional policy was very high. It was prepared very quickly under the competence of the Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic, although the legally competent body for regional development was the Ministry of Transport, Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic.

The Act defines the term ‘lagging district’ on the basis of the unemployment rate (the unemployment rate of the district must be more than 1.5 times higher than the national average during at least 9 out of past 12 months (§3)). This criterion is rather simplifying the multifactorial assessment of the level of development of a district which includes economic, social, cultural, environmental and other aspects; however, this was a pragmatic measure as the unemployment is easy to calculate. It is objectively measurable and linked to the legal administrative units at the level of LAU1. It also follows the key objective of the support based on this Act—to increase the availability of jobs and support the endogenous bottom-up driven regional development.

The priority of this branch of policy for the national government was accentuated by a shift of competences to the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic for Investments and Informatization. Before this shift of competences, the government created the office of government plenipotentiary for lagging districts with a team of experts who supported the action plan implementations in close cooperation with the national government and the ministries on one hand, and, crucial local stakeholders from the public, private and NGO sectors on the other hand.

The Act no. 336/2015 Coll. Defines new tools and their basic content without going into details, while reflecting the need for flexibility and mirroring the specific situation in particular districts. The implementation was the absolutely crucial part when determining their aim by defining their basic philosophy, focus and the basic underlying principles. The tools specified by the Act are not only new, but can be appointed as innovative, introducing the elements of polycentric multilevel governance into the practice of regional development management as defined by E. and V. Ostrom, who view polycentric governance as having three preconditions: (1) multiplicity of decision-making centers; (2) the overall framework provides overarching system of rules, and (3) spontaneous social order as the outcome of evolutionary competition between ideas and methods [

22]. Within the EU, such a system in practice has been termed as multilevel governance. Not only has the system started to be multi-level with different decision-making centers at different levels [

23], it is also characterized by an increasing tendency to invite executors outside the hierarchical administrative arrangement [

24]. The principles behind the support of lagging districts described in this paper are implementing the characteristics of multilevel polycentric governance into practice by fostering open governance, creating conditions for bottom-up processes and promoting self-organization of management system in the regions.

There are many definitions of multilevel governance, but what the majority of them have in common is the fact that they describes processes or re-allocation of authority out of central states [

25], i.e., advocates for better coordination between the hierarchical, top-down levels and the sectoral, problem-oriented jurisdictions. This is done in order to foster transparent, open and inclusive policy making processes, promote participation and partnership, foster policy efficiency, policy coherence and promote budget synergies, as well as respect subsidiarity and proportionality in policy making and ensure maximum fundamental rights protection across all levels of governance [

26]. Multilevel governance is characterized by flexibility and adaptability [

27], self-organization, spontaneous development and experimentation [

22], as well as dealing with fuzziness—managing increased mobility of citizens and their territorial belonging [

28].

4. Methodology

In December 2015, the new law on the support of lagging districts came into force. One of its effects was the creation of an expert group to offer technical assistance with preparation and implementation of the action plans. One of the authors of this paper had been a part of this expert group and was directly involved in preparation of the law and the action plans for lagging districts. In February 2016, the first action plan was accepted by the national government and within the next 6 months, 11 other pilot action plans were accepted as well. In 2018, the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Republic approved a research project called ‘Institutional environment as a vehicle of development policies in least developed districts‘. The project’s objective was through innovative combination of conventional and alternative analytical methods and an interdisciplinary approach to solve the absence of inter-sectoral and inter-level coordination and subordination, and the consequent absence of synergy of regional development policy and tools. This is achieved by focusing on the newly formed institutional configuration in terms of Act no. 336/2015 Coll. on the support of lagging districts as a unique opportunity and a certain form of a "laboratory" for analysis of the dynamics of institutional framework evolution in the background of the policy implementation process.

Within this project, the steps were as follows: (1) identify key advocates in institutional environment within different hierarchical levels and thematic areas in the process of formulating and implementing regional and local development policies and strategies; (2) identify the horizontal and vertical relations between each of the advocates within all relevant dimensions (flows of information, financial and material flows, cooperating in formulation and implementation of strategies and specific activities, informal relationships, etc.) as well as to identify the dynamics of the evolution of these networks in time; (3) identify the interdependence and synergy of individual relations; (4) identify the ‘bottlenecks‘ in the functioning of institutional networks in the implementation of regional and local development policies and the "critical paths" of individual flows within the institutional network; (5) identify the factors of emergence of bottlenecks and barriers in the functioning of institutional networks; (6) identify the existence, nature, volume and impact of transaction costs in an institutional environment; and (7) deliver the recommendations to prevent the emergence or eventual elimination of problems and barriers in the functioning of the institutional environment and to ensure its more effective action in terms of achieving unbiased objectives of relevant policies.

Additionally, within the scope of this paper, we identified and compared the trends in the development of selected indicators (data for unemployment, labor productivity and other available indicators from the Employment Institute of the Slovak Republic) on a defined time series. Based on the comparison of the values of selected indicators at a predefined time series and at different levels (local, district, regional, state), trends in the development of these indicators at individual levels were identified. With regard to the spatial local specificity of the implemented measures, deviations in the development trends of time series of monitored indicators were monitored to identify the effects of these measures and their impacts on selected indicators in the monitored time. A great limitation of the research was the absence of relevant data at NUTS-4 (LAU1) level since the majority of the data are collected at national and/or regional (NUTS-3) level. Another limitation is a general lack of data collected by relevant public authorities and their availability.

5. Principles of Support for Lagging Districts

The action plans as projection documents approved by the national government focus on removing socio-economic backwardness and reducing high unemployment rates in lagging districts. Their aim is to channel the support for integrated strategic projects rather than to support isolated activities. The objective remains to create sustainable employment via sustainable jobs creation and target-oriented support of economic development in the districts. Therefore, the action plan is a key management tool and not a goal on its own; it is a means to improve the quality of life by integrated action focusing on the strengths within each particular district and a potential efficient use to initiate their growth. The action plans are open documents, the performance of which is annually evaluated. They are adapted according to the specific needs of each region.

The basic structure of the action plans for lagging districts is given by the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. The act, however, does not define any principles which these plans are based upon. The expert group as the established body of experts, which was supporting the local executors in preparation of the action plans, formulated these principles as working guidelines. One of the authors of this paper was a member of the expert group. The principles below and the tools that this new approach to the development of lagging districts deliver are based on this experience, on the annual evaluation prepared by the Governmental Office of the Slovak Republic and by the research conducted by the academic sector titled ‘Institutional environment as a vehicle of development policies in least developed regions’ granted by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Republic.

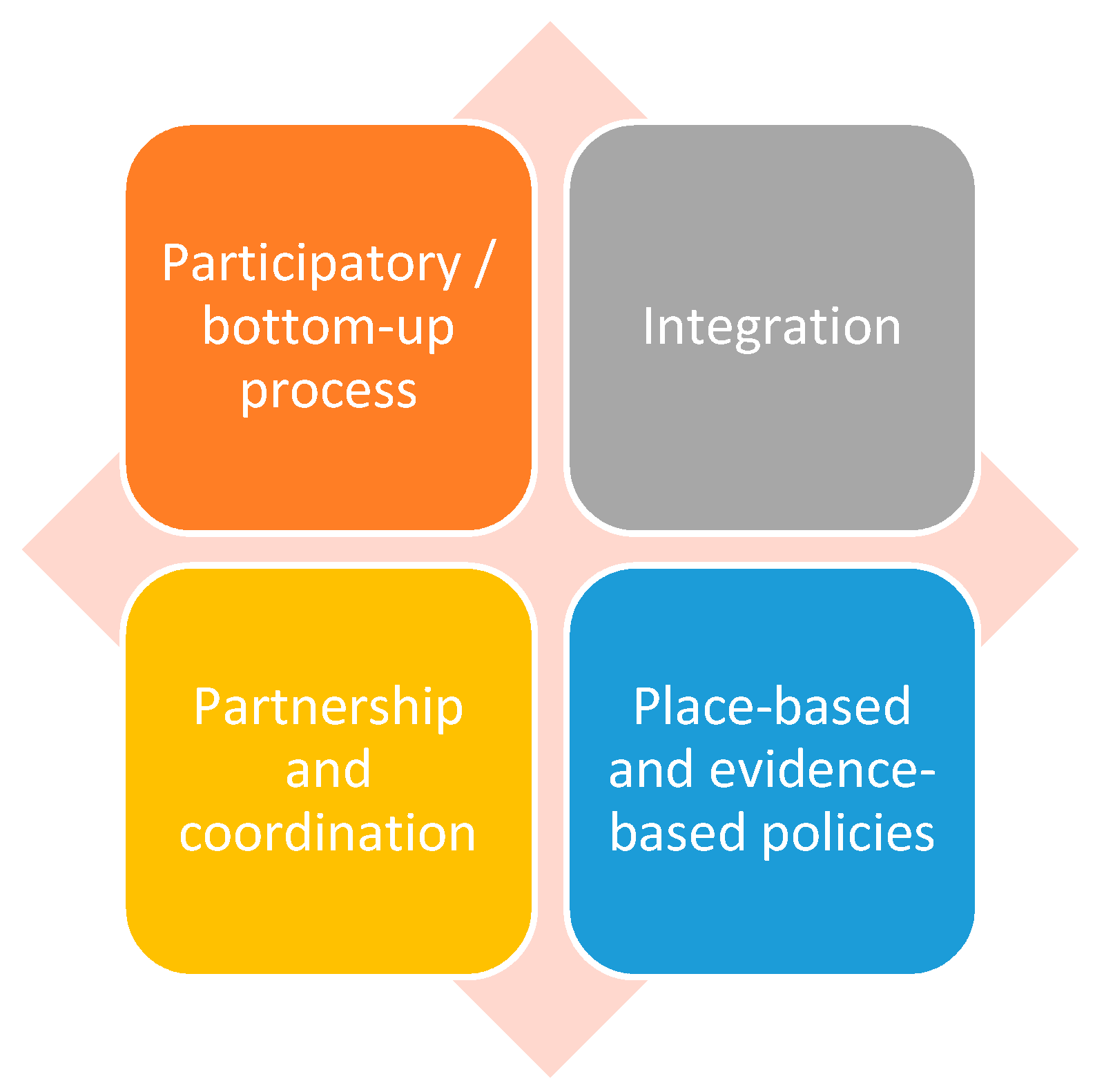

The action plans were prepared by local actors under the support of the group of experts from various branches of regional and local policy, including representatives of academia, public sector and professional organizations. This expert group defined the principles which the action plans were built on. These include participation, integration, partnership and coordination, and place-based and evidence-based policies (

Figure 1).

5.1. Principle of Participation/Bottom-Up Approach

Firstly, the whole process was aimed to be conducted in a participatory way from the very beginning, i.e., in the bottom-up way, and the role of state administration and experts was clearly defined. On the one hand, their input was their professional technical knowledge, offering practical knowledge and initiating the cooperation structures to launch the development of districts based on the potentials and local territorial capital. On the other hand, they were mediating the process of creating a participative definition of the action plans. The mediation process took place between different local stakeholders, local and regional authorities, entrepreneurs, schools, state administration representatives, NGOs, citizens and other parties in order to properly address the needs and use efficiently the potential of the districts and ensure involvement of all partners in their implementation and the sustainability of the effects of action plans. For the first time as well, the Act no. 335/2015 includes local economic executors as part of the regional development process and methods of strategy preparation and implementation.

5.2. Principle of Integration

Secondly, the key principle of integration was manifested in developing a comprehensive strategic document, although the central aim of the action plans was to create working places and lower the unemployment rate. The implementation of the integration principle was supported by organizational changes as well—by shifting the responsibilities from sectoral ministry (the Ministry of Transport, Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic) to the Prime Minister Office, later on to the Deputy Prime Minister Office. This should eliminate the long-lasting problems resulting from the lack of coordination among sectoral ministries responsible for particular aspects of regional development, which were not in unison, resulting in a lot of miscommunication and time delays. Therefore, one of the key objectives of the action plans was a strengthened cross-sectoral cooperation. Since 2016, the regional development has become a competence of the Prime Minister’s Office, whose objective was to use the higher authority in coordination with sectoral ministries and regional policies, including the policies for the development of lagging districts in Slovakia, including funding of these policies and action plans.

Another highly relevant aspect of the lack of integration was manifested by insufficient integration of key advocates from both public and private sectors into the processes of regional development. The processes of regional development were mostly regarded as a pure matter of the state (public sector), i.e., separate from other advocates (private advocates, NGOs, citizens). In reality, the regional development is a highly complex issue requiring an integrated approach, where all relevant actors play their role and are responsible for it. It is not only about the state support and strategic documents prepared by legal bodies of the state, but an interplay of the key relevant actors for successful regional development. In the same vein, sectoral types of approach dominated, which meant single viewpoints by sectors (ministries) were overshadowing the complex nature of the issue. The problem with the sectoral approach is a lack of integration leading to a lack of synergies and inefficiency in the processes.

5.3. Principle of Partnership, Vertical and Horizontal Cooperation

Thirdly, the principle of partnership and coordination was manifested in the institutionalization of the cooperation structures absent in the districts. The crucial problem of public governance bodies in the districts was the lack of awareness of their role in the regional economy and from the past continuing paradigm that the state should look for all strategic investments and ensure funding of the development. The local governments were unaware of their tasks; however, more profoundly of their position and significance in the national economy. This led to the ‘waiting strategy’ where the local government was waiting for investments to come, infrastructure to be built and maintained etc. This crucial shift in the approach and mindset of the local government is the key in the principle of partnership, where local advocates have got a place at the decision-making table and are viewed as relevant stakeholders in the local and regional development together with the state, private actors, NGOs etc.

The role of key economic players was revealed as they are the key drivers for the economic development in cooperation with the public sector. The principle of partnership is demonstrated in the way that cooperative structures are created between the public and private sector—regional boards (see below in

Section 5). These sectors used to cooperate scarcely and were both working in silos. The aim of the regional boards as cooperation structures is to create a forum where the problems and solutions are discussed and negotiated and the role of each partner in the regional development is negotiated and agreed on.

Vertical cooperation was the task of the expert group to mediate with the national government, help local stakeholders to create and implement projects for local and regional development, as well as help the local advocates to provide arguments for the proposed activities in the action plans. The action plans as a tool need to respect the strategic documents at all levels (local, regional, national and supranational level), and this coordination needs to be followed in accordance with the legislature.

5.4. Place-Based and Evidence-Based Strategies and Approaches

Lastly, the policies were prepared on a place-based and evidence-based principle, i.e., utilizing the local potential and the local territorial capital in order to ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of the proposed measures. The action plans were prepared by the local stakeholders with some support from the expert group. During the preparation of the action plans, the members of the expert group helped to analyze the local capabilities and limitations, crucial stakeholders, positive examples of activities, and identify relevant transferable knowledge, principal stakeholders and their capacity for cooperation. Their expertise was completed by the role of mediators, increasing the efficiency of the action plan development processes, including the definition of pilot actions, while demonstrating the benefits of cooperation between the public and private sectors. The inputs of the expert group as persons from the outside facilitated discussions about solutions, and their knowledge provided a contribution to the pilot projects. An important aspect allowing this was the societal authority of the experts representing independent and broadly accepted expertise from the business sector, planning, civil society, as well as communal politics.

Another cross-cutting issue was the lack of capacities for regional development management on NUTS3 level and NUTS5 level and a clear need for a more efficient management approach and methods on an intermediate-level. The decision was taken in order to prepare the action plans and to develop related activities at the LAU1 level (in Slovakia only a statistical level and not officially recognized level of administrative units in relation to Act no. 416/2001 on transfer of some competences from the state administration to local and regional bodies [

29]). This meant the need to use informal instruments as the formal ones did not exist at this level.

6. Innovative Tools for the Support of Lagging Districts

The Act no. 336/2015 Coll. defines a set of tools aimed at removing the backwardness and improving the quality of life in the districts eligible for support according to the specific criteria—the unemployment rate of the district must be more than 1.5 times higher than the national average during at least 9 out of past 12 months (§3 of the Act no. 336/2015). There are six of these tools and these, together with some experience from their implementation, can be described as follows:

6.1. Action Plans

Description: The action plan is a document approved by the national government aimed at removing the lagging behind of a designated district in the economic and social performance (§4 of the Act No. 336/2015). The plan must be in accordance with the superior planning documentation and integrate the existing sectoral programs. The action plan consists of a set of proposed measures to remove the barriers in the development of each district on the basis of sound analysis of the district’s needs and potentials. The strategy is prepared for a five-year period and the measures are planned on an annual basis (akin to a roadmap). The annual priorities include a list of activities in the district to be implemented for each respective year and a list of projects financed or co-financed from different sources, especially “regional contribution” (see below).

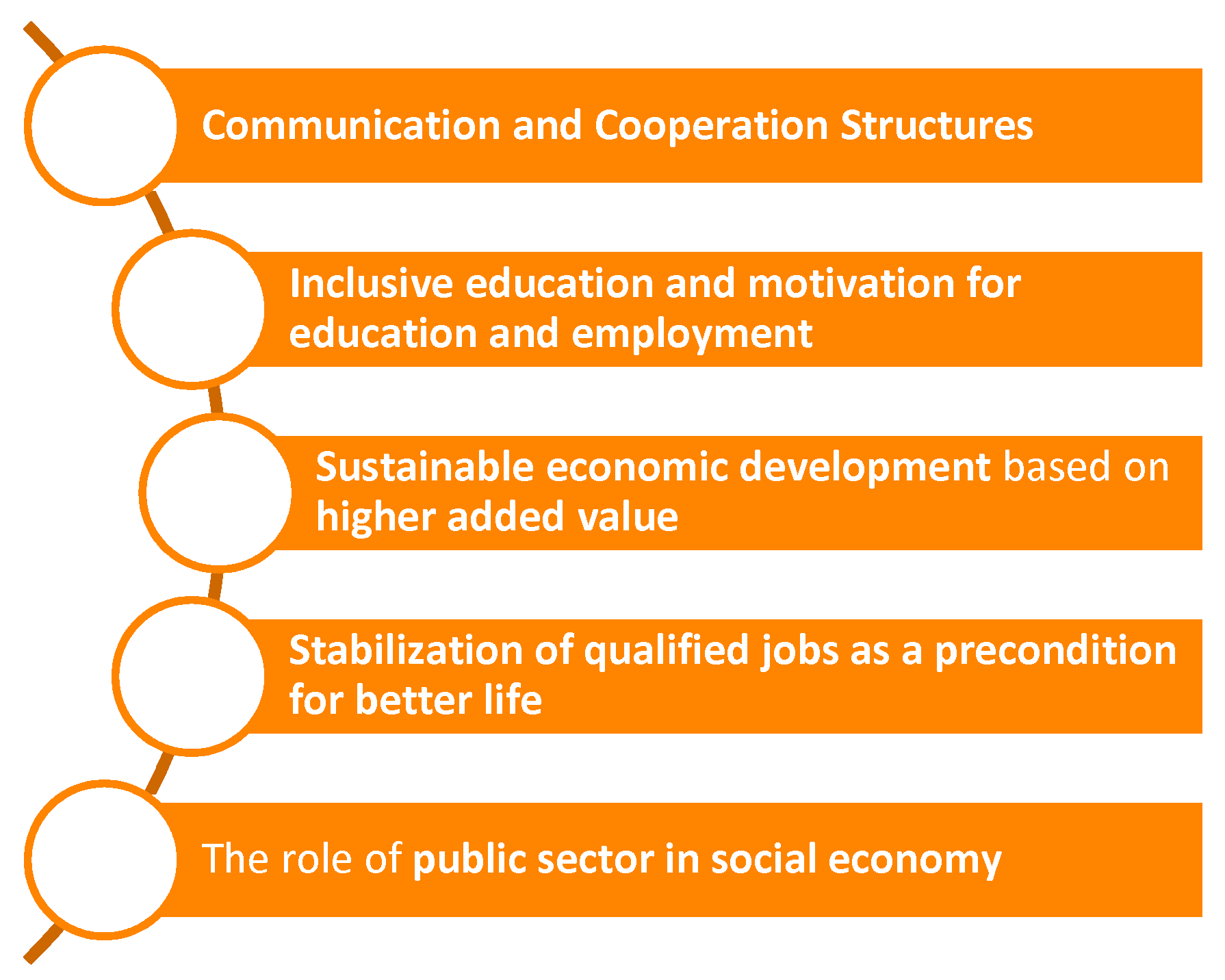

The action plans had been built (as proposed by the experts) on five pillars (

Figure 2) in order to achieve their objective to improve the quality of life through primarily focusing on creation of sustainable jobs. These pillars offer a framework for key topics to be included in the action plans to reach the greatest target group, ranging from small children (the principle of inclusive education) up to adults of working age, striving to make a good living for their families (the principle of stabilization of qualified jobs).

The first pillar is building communication and cooperation structures as a precondition for a successful framework for cooperation. It is based on the principle of participatory process and a partnership principle where the plans are co-created by the communities, the local politicians, NGOs and the experts from inside and outside of the districts [

30]. The plans need to be prepared as a consensus among the key stakeholders where each contributes with their knowledge, expectations and willingness to be a part of the process of plan making and plan implementation [

31]. Furthermore, necessarily, these cooperation structures are supposed to remain in the district for the implementation as well.

Inclusive education was defined as the second pillar considering the low level of school attendance and low number of graduates. Education is the basic precondition for sustainable employment and employment in sectors with high added value. Inclusive education signifies both persons with disabilities as well as people from minority groups whose level of education and school attendance is frequently low in these districts. It is an instrument for improving the quality of labor force and consequently quality of life for whole families. It was important to create incentives for individuals to ensure school attendance and finishing the basic level of education not by repressive means (e.g., conditioning child support based on school attendance), but to positively incentivize this by local examples that are well-known.

Thirdly, sustainable economic development must be based on employment grounded in the high added value of products which are directly linked to higher salaries and working conditions. This is opposed to seasonal and temporary (as well as illegal/black) jobs, the occurrence of which is uncertain and unregulated by the state. Additionally, these jobs need to be efficiently capitalizing on the territorial capital (natural, social, economic) as the basis for creation of new jobs. It is vital to use the economic multiplier effect in the territory in order to create high added value products (as opposed to exporting raw materials to be manufactured elsewhere) and then to export these nationally and internationally.

Another question that has arisen during the process of working in the lagging districts was the stabilization of qualified jobs and enterprises by providing access to enhanced conditions for life and economic activities. The workers need to understand that being economically active brings them a lot of benefits and these benefits surpass the benefits of being jobless and relying on state social support. In this way, sustainable employment can be achieved when workers are proud to be employed and want to improve their life by advancing in their jobs.

Lastly and perhaps, from the viewpoint of the public sector most crucially, there was a need to re-introduce the role of the public sector in social economy. This concept became foreign for various reasons and was infrequently mentioned as the processes of neoliberalization in the national economy leading to a point where free market was believed to resolve all issues with limited state intervention. It led to a situation where the public sector became obsolete and lost the means, motivation and confidence in its role within the districts and their development. The fundamental part of the action plan and the plan-making process was to include the public sector workers and activate it since they as local actors are familiar with the local conditions, potentials and problems, have extensive experience in these districts, and, in the end, the public sector is responsible for managing the local economy.

Implementation: Although the structure of the action plan has not been prescribed, all lagging districts followed the framework of five pillars as shown in

Figure 2. The action plans are understood as the main tools for coordination of varying measures, actions and open documents, the yearly update of which allows stakeholders to react flexibly to changing framework preconditions and reflect on progress and failures in their implementation process. The main problem in the implementation of the action plans are the administrative barriers for financial support for particular actions/projects, as well as continual sectorial organization and lack of flexibility of operational programs of the EU structural funds not allowing for properly addressed interventions for the improvement of situation in lagging districts.

Benefits/evaluation: The action plan as a tool brought two main benefits. The participatory process of their development created the base for integration of the whole scale of stakeholders into the regional development and creation of the informal cooperation structures at the level of LAU1. It opened the way for coordination of majority of activities relevant for regional development independently from their driving force and safeguard the complementarity with the interventions focused on catalyzing and supporting the regional development.

6.2. The Council for the Development of Lagging Districts (the Council)

Description: The Council is an advisory body of the Slovak government for matters related to the support of lagging districts. It is a formal institution which consists of the Director of the Council, the Vice-director and its members. The Director of the Council is the Deputy Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic for Investments and Informatization and the Vice-director is the head of the Government Office of the Slovak Republic. The members of the Council are representatives of ministries of the Slovak government and heads of the municipal offices.

The role of the Council is to support coordination, consultation and professional tasks related to the support of lagging districts, to propose systematic measures for improving the effectiveness of the support of the lagging districts provided for the Slovak government, to discuss the proposal of the action plan and the proposal of annual priorities and adopting positions to them, and to participate in the monitoring and coordination of the action plan and the annual priorities. The Council additionally establishes regional boards for each of the lagging districts.

Implementation: The Council was the driving force behind the initiative to support the development of the lagging districts since its beginning when the Office of Plenipotentiary of the Slovak Republic was established. It was a formal instrument serving as a platform between the level of the lagging districts and the Slovak government.

Benefits/evaluation: This instrument did not fulfil all its expectations as the representatives of the sectoral ministries do not have the decision-making power. Further, this instrument was not intensively operating in the sectoral issues of the districts especially in relation to directing the flows of the EU structural funds.

6.3. Regional Board

Description: Regional boards are informal instruments created and enabled by the Council for the Development of Lagging Districts. They create the only platform at the LAU1 level which is supposed to bring the key actors together. The regional board is preparing the action plans in close cooperation with the expert group; it nominates the members to the Council, prepares the list of annual priorities and monitors the implementation of the action plans. The regional board also creates the project centers as its logistic support. The project centers are implementing the action plans by supporting the preparation and implementation of the projects from the action plan.

Implementation: As the structure of the instrument of the regional boards is not defined by law, their operation and organization vary. In some regional boards the head is the mayor of the district town, head of the municipal office or an NGO.

Benefits/evaluation: Regional boards for the first time provide coordination at the district level and they foster the bottom-up approach to policy making at the regional and local level. They offer a communication platform at the district level, bringing together relevant advocates in the territory.

6.4. Regional Contribution

Description: Regional contribution is a financial contribution from the state budget approved by the national government passing the action plan. The executive office mediating the financial flows is the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office in accordance with the action plan and annual priorities (§8 of the Act no. 336/2015 Coll.). The Act further defines the conditions for eligibility for the subject to obtain money from the regional contribution.

Implementation: By approving the action plans, the Government of the Slovak Republic allocates the framework of a yearly financial contribution beginning with the action plan implementation. Each year, in accordance with the state budget and state of implementation of action plan, an executive financial plan for each particular lagging district is approved. Each financial allocation is bound to a defined number of newly created working places.

Benefits/evaluation: Regional contribution should be complementary to the resources allocated from structural funds for particular projects included in the action plans and supporting the creation of work places and lowering the unemployment. Majority of the projects supported by the regional contribution has only indirectly been connected with the creation of work places and are much more focused on improvement of living preconditions in designated lagging districts. Due the administrative barriers and continual centralization of financial management at the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office with limited capacities, only a small part of the allocated financial resources reached the designated areas within the planned time. The problems with the regional contribution flows revealed that the financial support has not been decisive in terms of how successful the implementation of the law has been in the support of lagging districts. Much more important was the signal sent by the government by implementing a strategic approach involving the activation of local stakeholders and development of their own coordination structures as the partners in the dialog with the state government and all stakeholders in the districts.

6.5. Office of the Plenipotentiary of Government of the Slovak Republic for Support of the Lagging Districts

Description: The Office of the Plenipotentiary of Government of the Slovak Republic for supporting the least developed districts should be understood as one of the first measures of the new approach to development of the least developed districts, bringing the agenda from sectoral ministries to the office of the Slovak government. The plenipotentiary has had executive, decision-making, coordination and monitoring power over the agenda of support for the designated districts. Among other competencies, the Office of the Plenipotentiary created an expert group consisting of professionals assisting the district when preparing the actions and during their implementation.

Implementation: The plenipotentiary was appointed by the Government in 2015 and created a small team efficiently starting the implementation of the new Act. Due to the lack of management capacities in the Regional Development Section of the Ministry of Transport, Construction and Regional Development of the Slovak Republic, the team of plenipotentiary had to cover a broader spectrum of conceptual and executive activities related to regional development. This was one of the reasons for the shift of responsibilities in the field of regional development from the Ministry to the Governmental Office. The authority and competences of the position of plenipotentiary did not correspond with the need for stronger inter-sectoral coordination and coordination with the management of structural funds. As a result, after 3 years of the coordination of the support for lagging districts, it was integrated with the coordination of structural funds and investment under the umbrella of the Deputy Prime Minister’s Office. By way of this integration, the office of the plenipotentiary was cancelled.

Benefits/evaluation: Establishing the Office of the Plenipotentiary signalized that the regional development had become a priority for the Slovak government and it was aimed at simplifying the technical and financial support for specific districts. Besides supporting the districts through preparation of the action plans, the expert group was helping the lagging districts to initiate their endogenous development and set up the governance arrangements more efficiently and in a more participative way. The practice showed the necessity for stronger competences of a coordinating body than the position of the plenipotentiary and their office had provided, and later even demonstrated the need for organizational and institutional changes in response to the request for more strategic and integrative approaches.

6.6. Expert Group

Description: The expert group was established under the Office of the Plenipotentiary as a technical help with preparation and implementation of the action plans for the lagging districts. It consists of professionals with experience, authority and results in regional development. The selection of experts was reflecting the needs of a specific district in coordination, planning and project preparation; in the preparation of business activities, including agriculture, energy and social economy actors; in education, from day-to-day activities to obtaining professional certificates for the unemployed (who did not complete the primary or secondary education); integrating socially deprived citizens without work experience; management, monitoring and control. The expert group was organizing and guiding the work of the regional board. While searching for practical solutions it was preparing proposals to reduce the unemployment rate. It was ensuring the transfer of experience, ideas and knowledge in order to support the creation of an effective action plan. It was coordinating the communication with central state administration and their cooperation with the regional boards in the creation of the action plans, their negotiation and preparation for approval in the Government of the Slovak Republic.

Implementation: The expert group included representatives of communal politics, civil society, business in industry and agriculture, culture and minorities, tourism, academia, environment, civil society, and infrastructure engineering. They prepared and supported the implementation of the law from the strategic conceptual viewpoint, mediation and creation of cooperative structures in the lagging districts, development of action plans as well as preparation and implementation of particular projects and actions. After shifting the competences from the position of plenipotentiary to the Deputy Prime Minister, the role of group of experts was overtaken by the employees of his office.

Benefits/evaluation: The expert group played a crucial role in the implementation of the law as for the support of lagging districts. The trust and authority that the group developed in the contact with the stakeholders in lagging districts was a turning point for their active involvement in joint planning and implementing activities. This group worked with the highest efficiency, in one year supporting the development of 12 action plans and preparation and implementation of more than 100 projects.

7. Results—Experience from the Lagging Districts

The following part evaluates the progress in the 12 lagging regions designated for special support in accordance with the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. We are looking at the change in the unemployment rate, the number of created jobs and the labor productivity data. A big issue remains the lack of available data, in particular at the NUTS 4 (LAU 1) level and the lack of tracking additional data which could help evaluate the policy impacts.

7.1. Unemployment Rate and Created Jobs

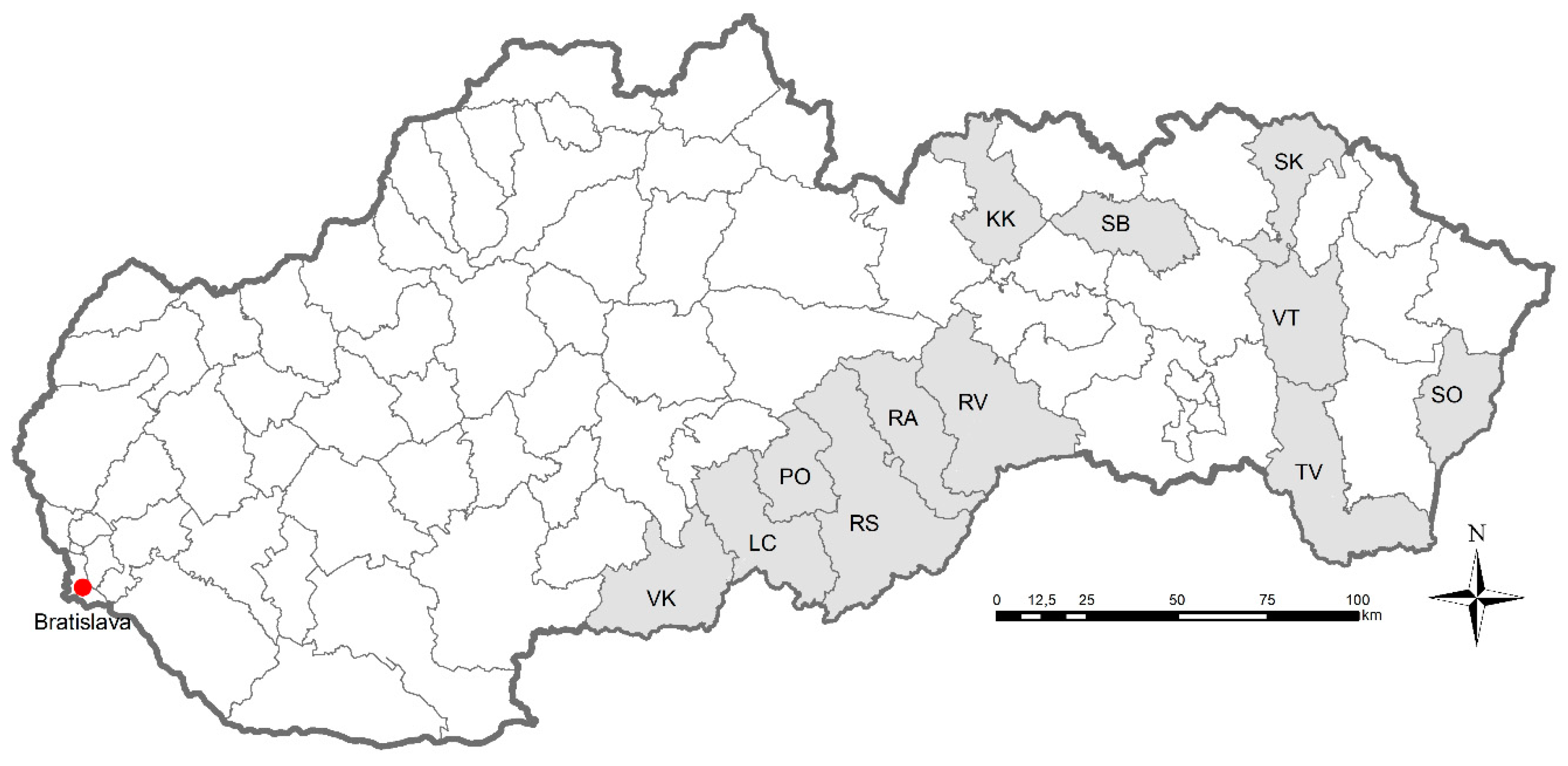

In 2015 the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. was enacted and came into force. Overall, 12 pilot lagging districts had been selected as a subject of this Act and were eligible for special support from the national government (

Figure 3). The districts were selected according to their percentage of unemployment and the unemployment level was in excess of 25% on average.

For several months the expert group, appointed by the Plenipotentiary of the National Government of the Slovak Republic, had been preparing the actions plans for these districts, aiming at improving the conditions for creation of sustainable jobs (i.e., jobs which remain after the subsidies expire, as opposed to subsidized jobs, which are eliminated after the support expires). These plans were gradually accepted by the national government and put into force until the end of 2016.

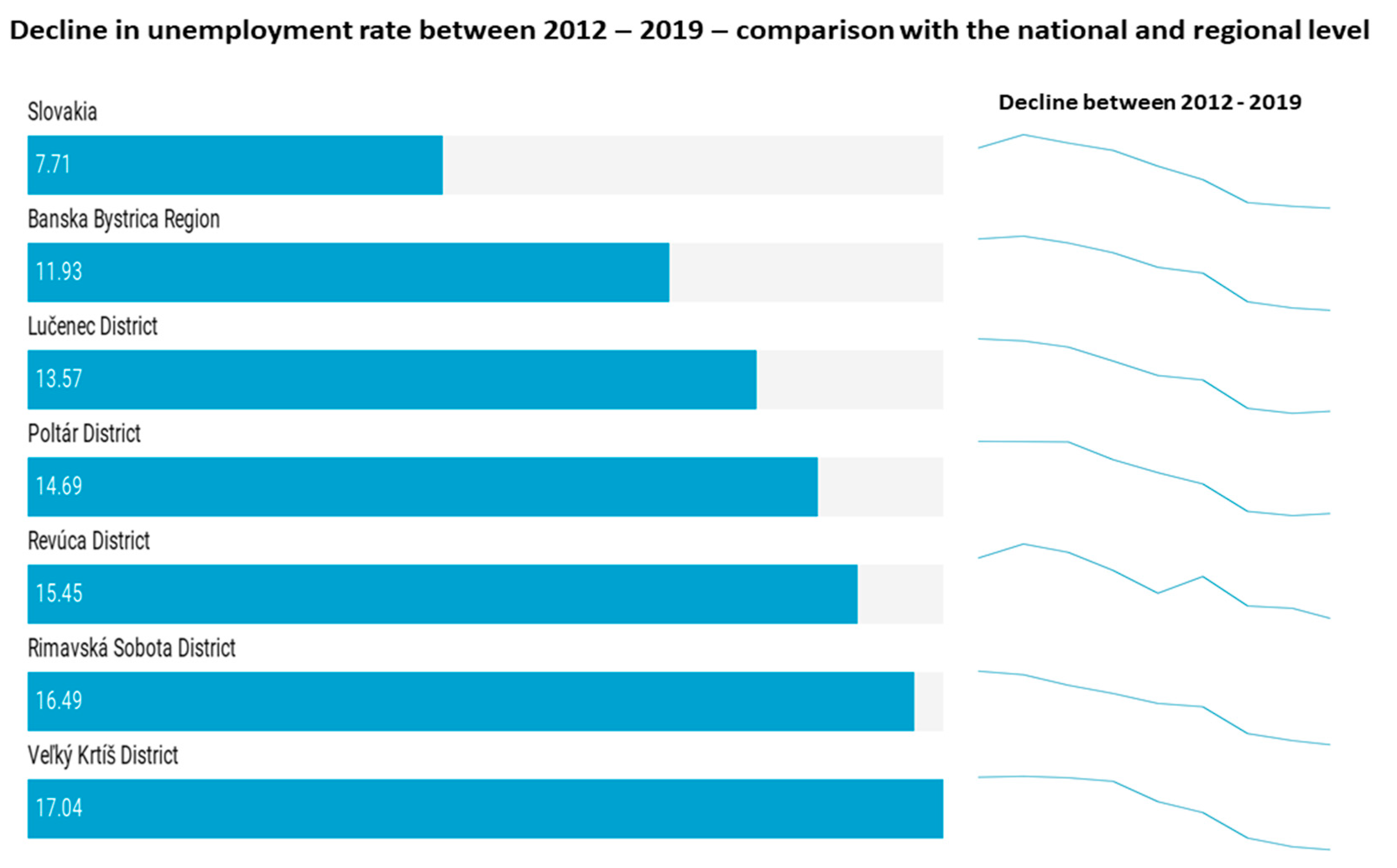

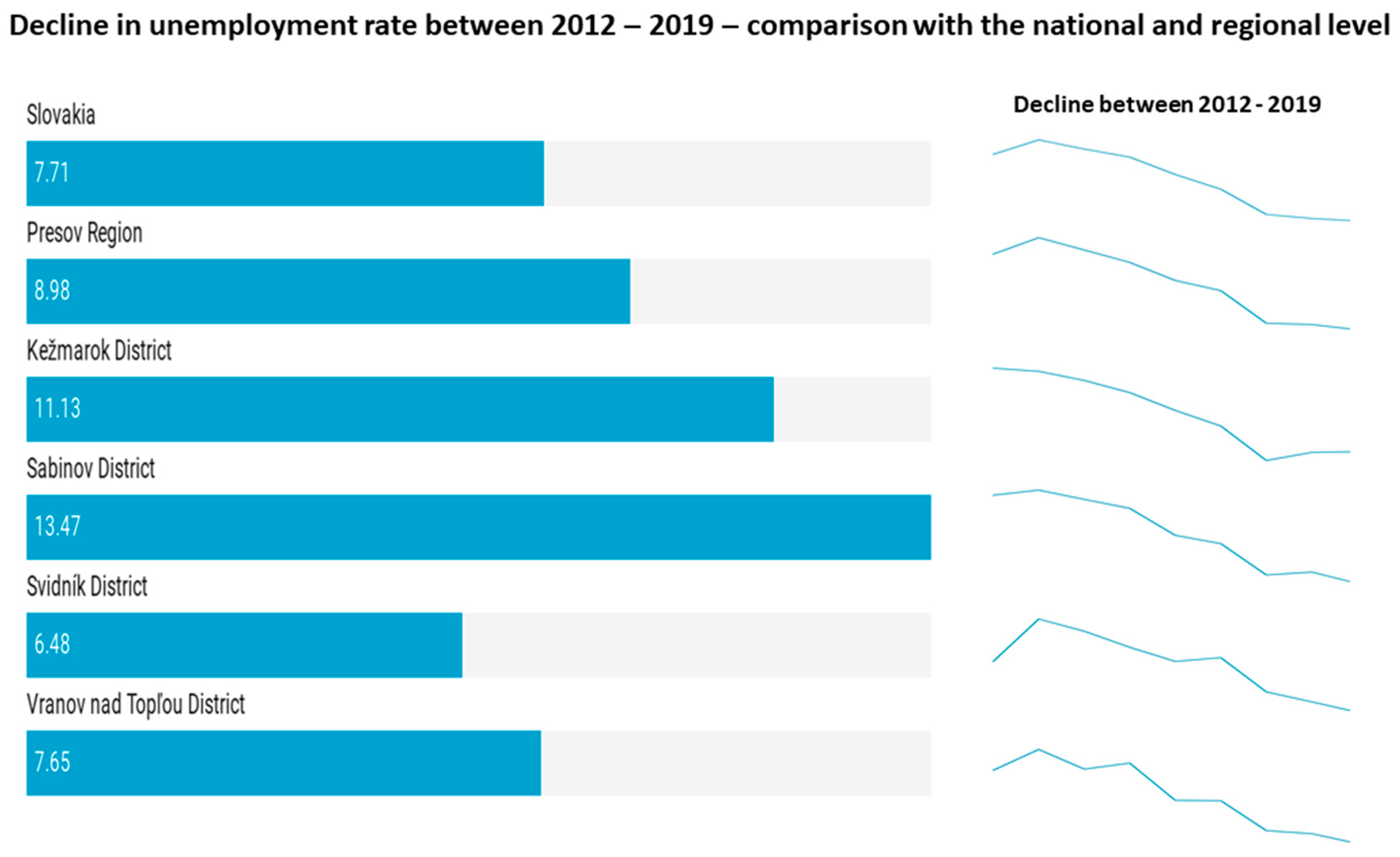

The

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 demonstrate the decrease in the percentage of unemployment rate between January 2012 and December 2019 in 12 lagging districts, which were eligible since 2015 for the special support. The comparison with the unemployment rate at the national and regional (NUTS3) level is disclosed to represent that the decline in the unemployment in the designated regions is larger and steeper than the national average or their respective regional average unemployment rates.

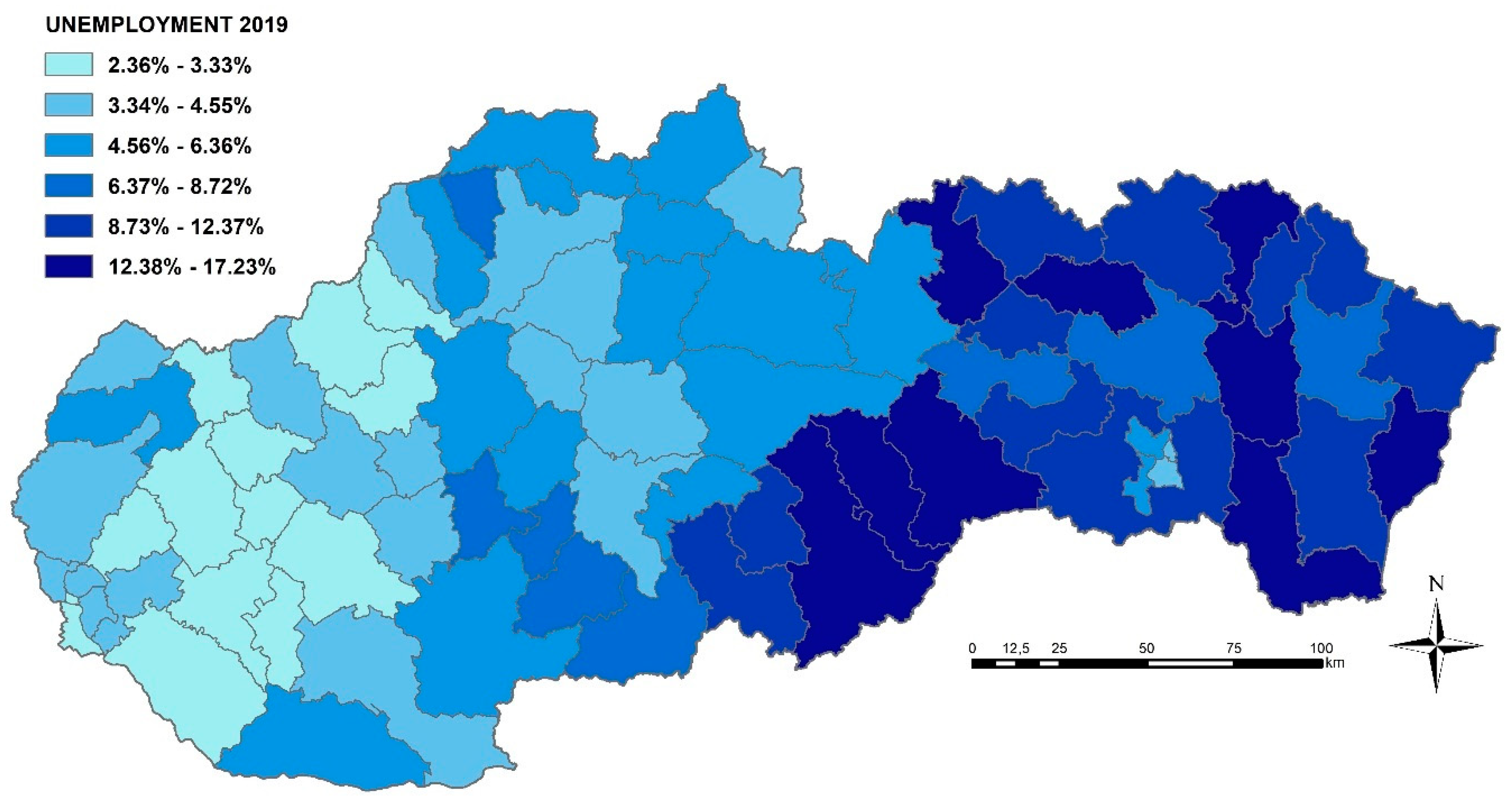

Figure 7 represents a decline in the unemployment rate at the district level in the whole of Slovakia (the darker the color, the greater the decline is in the unemployment rate).

Table 1 sums up the available data on the 12 lagging regions and their comparison with Slovakia. We can see that the number of citizens in these districts remains stable and the number of unemployed persons decreases gradually, similarly to the number of beneficiaries of unemployment support subsidies. The level of long-term unemployment rate decreases as well, although it still remains high when compared with the national average.

It is clearly visible that the decrease in the unemployment rate was the greatest in these districts. When compared to the change in the unemployment rate in other districts and when compared to the regional level, the districts eligible for increased state support and using other aforementioned support planning tools were more successful and demonstrated a larger decrease in the unemployment rate, which is indirectly linked to the increase in quality of life and economic and social well-being of the citizens. Other districts in Slovakia did not implement most of the tools described in

Section 5 (they did not implement a strategy at LAU 1 level; did not create these place-based and evidence-based policies; the absorption of the financial support was not as high as in the lagging districts; the management structure was more formal, top-down oriented; the progress can also be perceived in the attitude of the advocates among them towards the national government) and when we compare the development of their unemployment rate, it was progressing less steeply.

7.2. Labour Productivity Growth

The labor productivity rate in Slovakia has increased between 2009 and 2016 and OECD characterizes this growth as relatively strong [

34]. These data are not available on the NUTS 4 (LAU 1), but OECD [

34] also argue that the productivity growth between the regions of the Slovak Republic does not vary much in OECD comparison, and thus we argue that the growth in productivity also occurred in the lagging districts. This productivity growth is sometimes also called the Slovak miracle by the OECD experts. The growth in productivity in manufacturing (measured according to the GDP per hour, percentage change at annual rate) over the period of 2014-2018 was the second highest in Slovakia (after Ireland) [

35].

8. Discussion

8.1. Challenges of the Action Plans

During the first years of the preparation and implementation of the action plans, several challenges were identified. The initial challenge was the negative first perception by the locals, both local politicians as well as the local people. Their experience from the past taught them to be cautious of the activities brought from the capital city. This experience was not unique as several times in the past they remained disappointed by the lack of results after enormous promises. This led to the second challenge of lacking the will to collaborate, in particular in the beginning of the initiative. Oftentimes, in the local perception, they were supposed to wait for the stimuli from outside of the district, such as hoping for investments to come to improve their lives. Overcoming this passive attitude was crucial as well as fostering the feeling of their role and importance in the regional economics.

Thirdly, the suggested financial coverage still remains an issue from at least two viewpoints. At first, the allocated funding is supposed to be covered from the European Structural and Investment Funds and this source of funding is uncertain until the money is approved for a particular project. This type of funding covers the vast majority of allocated finances. Furthermore, the implementation is project-based and the projects are following in a particular order. The problem occurs when one project in the whole chain is not approved and the sequence of projects with a specific objective is interrupted.

The action plans still remain as a non-system solution which is destined to be short-term and is supposed to become a part of a whole new legal act managing the regional development in Slovakia. Currently, there is a duality of legal acts dealing with regional development when two acts are active in parallel. Consequently, this advances the issue with coordination and administration capacities both vertically (local up to national level coordination) and horizontally (among the branches of public policy at one level).

Several bottlenecks remain in the implementation of the action plans. At the local level, it is the need to make a provision for the local institutional specifics of the given district and insufficient local capacities, which can be seen in long delays in the decision-making processes. The representatives at the national level are then faced with a need to decide whether to wait or to intervene and at the same time limit the power of the local actors. All of these deficiencies are contradictory to the main objective of the action plans in such a way that they lead to frustration and lack of trust for further implementation of the action plans [

8].

8.2. Perspective for the Future

The experience over the past 5 years from lagging districts of Slovakia provides evidence that this approach of creating very specific, evidence-based, territorial capital-based action plans, produced in an open and participatory way, are potentially positive tools for advancing regional development, not only in lagging districts, but transferred to the national policies for development of regions.

The acquired knowledge creates the basis for the preparation of the new national strategy of the regional development which will be eligible for the whole territory of Slovakia. The experts working in the field in recent years are involved in preparation of the document and it will become the strategy implemented within Agenda 2030. Within 2020, this strategy is expected to be finalized and enacted by the national government. The strategy is dealing with all districts including the economically advanced districts as this approach has a capability to foster the growth of all types of districts.

The issue of law duality related to the regional development is to be determined by preparing a new law on regional development which would merge the two existing acts and related legislature in order to be more appropriate and useful for regional and local stakeholders and streamline the complicated process of applying for funding and plan preparation.

One of the most significant results from this experience is the fact that funding the regions, while the clear strategy and involvement of all stakeholders in the districts is absent, is an inefficient misconception and delivers little result. The theme of regional development is highly complex with many factors and variables involved, and an easy solution to increase the funding is a misguiding and overly simplistic view. What is needed is a territorial capital-based inclusive strategy exposing the regional potential and then carefully and holistically designed projects to capitalize on this potential. Thus the life in the districts can be regenerated by creating various indirect effects besides a decrease in unemployment rate.

The experience also revealed the issues to be resolved, i.e., the key problems to be tackled. One of them is a lack of coordination in competencies on and among the various levels of the administrative system, leading to inefficiencies, delays and misunderstandings. This cannot be solved overnight by a quick fix; however, a focused effort of all involved actors is crucial.

9. Conclusions

The introduction of new support instruments for lagging districts framed by the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. was shaping the program aimed at restarting the economy and increasing the employment rate in the districts. From this point of view, it delivered a success story since when we compare the decrease in the level of unemployment rate in these districts, it was greater than other regions. We assign this decrease to the better framework conditions. Additionally, there had been many side effects and activities which led to decreasing the unemployment rate and other secondary effects in the long-term horizon. This, for example, includes stabilizing the labor force or improving the quality of life. However, these effects can only be genuinely measured in a longer time frame, while in the short run, the unemployment rate is one of the objective measures available. From this standpoint, even if the results vary, compared to the adjacent regions with similar conditions and not having the tools implemented that this new approach has brought, they can be regarded as the best practice examples since these action plans and other tools re-started the development of these regions and fostered the bottom-up approach capitalizing on their territorial capital.

The study describes the implementation of multilevel polycentric governance model and its benefits in balancing the disparities among the regions. It shows how it can be implemented by supporting better place-based and evidence-based policies and how the state can effectively intervene by creating improved framework conditions for the bottom-up development rather than on the principles based on the national operational programs of the EU Cohesion policy.

Even though it may be viewed as a non-systematic step introducing parallel instruments into the regional policy defined by the law on supporting regional development and the National Regional Development Strategy, this policy was a proper and flexible reaction to the need for the practice. The space it has created for local and regional stakeholders, flexible approaches, new instruments, interplay between local and regional governance structures, and the state government mounted into the relevant improvement of the situation in lagging districts and creation of new work opportunities. It opened the possibility for experimental approaches leading to innovative approaches and best practice examples, and clearly shows the necessity to define the national regional development policy in a new progressive way. The experience from the development and implementation of the action plans in the lagging districts revealed the barriers and problems, and at the same time possible solutions for their decrease and elimination. One of main lessons learned has been the implementation of the informal instruments and introduction of the supra-local level for the place and evidence-based regional development strategies (LAU1) as the local (LAU2) and regional (NUTS3) self-governing levels are not suitable for an efficient response to current regional development challenges. Creation of the coordination structures and participative elaboration and implementation of strategic development documents at the level of districts allowed the development and efficient implementation of much more target-oriented place-based strategies, activated local territorial potential and achieved synergistic effects between local actions and initiatives across different stakeholders groups. At the same time, it allows stakeholders to efficiently face the problem of lacking capacities at the local level, predominantly represented by small municipalities with less than 1000 inhabitants. Implementation of the Act no. 336/2015 Coll. opened the way towards new innovative approaches framed by the proposal of Vision and Strategy of the Development of Slovak Republic, which is the main implementation document of Agenda 2030 in Slovakia.