Abstract

Social innovations have been the subject of much academic discussion in recent years and have been approached from multiple scientific perspectives. This work sets out to determine whether innovations carried out by Andalusian olive oil cooperatives can be described in terms of social innovation and if they could run a main role as rural development actors preserving the competitive capacity of farmers and the living conditions in rural Andalusia. Through an analysis of the available literature, the use of municipal statistical data and the conducting of in-depth interviews, we show how cooperatives have been proposed as a solution to the problems that international competition poses for the production activity of olives and olive oil. At present, the most innovative cooperatives are undergoing a slow process of incorporating innovations, above all organisational and management ones, which reach beyond the entities themselves, given the social character that they have in the region, where they are considered a public good. Despite the problems that olive oil cooperatives have historically had in competing in the market, they can contribute to maintaining the population in the rural environment and improving the quality of life in the region, justifying the need for government support.

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Innovation in Rural Areas

Social innovation is a relatively recent concept that is widely used in the social sciences, such as economics, geography, sociology or politics. As innovation, the concept implies new initiatives, changes, approaches or proposals dealing with social challenges. The OECD says that “social innovation seeks new answers to social problems by identifying and delivering new services that improve the quality of life of individuals and communities, new competencies, new jobs, and new forms of participation, as diverse elements that each contribute to improving the position of individuals in the workforce,” [1]. Being social, the idea of social innovation is always related to collective action that seeks to change the relationship between agents, institutions, and society, giving rise to new institutions and new social systems [2].

New institutional economics has focused its attention on institutions—formal and informal social rules—and on actors to explain how agreements are reached and to understand the performance of economic development in societies over time [3]. Seen through this lens, social innovation is not such a new concept. Long-term structural changes in institutions—and other minor socioeconomic changes during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries [4]—came about through democratic revolutions in the past, although, nowadays, it is being used as an important tool to emphasise the necessary efforts local communities are making to face the challenges posed by globalisation [5].

In line with the work of Ayob et al. [6], we frame our research following the path paved by earlier researchers. Henderson [7] defines social innovation as a new form of relationship among different social groups locally settled, leading to social changes derived from the pressures on elites to assume new propositions. Sabel [8] highlights the new forms of social relationships among business, civil society, and local authorities. Mumford [9] focuses his attention on the implementation of new ideas in order to reach common objectives. Phils et al. [10] introduce synergy into the concept. Finally, Mulgan [11] defines social innovation as innovative activities encouraged by the goal of achieving social needs developed and spread by organisations whose main objectives are primarily social.

In accordance with the above, the study of how co-operatives introduce new responses to societal challenges in rural areas is at the core of the field of social innovations, as these organisations always deal with the empowerment of citizens, are bottom-up initiatives and propose more democratic governance [12]. Nowadays, rural areas and innovation are still strange bedfellows if we consider innovation in a technological way, very often related to close contacts between technological centres, universities, and large corporations well integrated into international value chains. However, there is no reason that a different approach cannot be taken with the concept of innovation.

Rural areas have been developing innovations for decades, with less interaction between agents, but strategic in terms of productive activities in order to adapt their competitive advantages to the new requirements of the markets. These processes of innovation have often been labelled “slow innovations” [13]; they were local initiatives responding to the restructuration challenges of traditional and agrifood industries in peripheral and core regions during the 1980s. Indeed, innovations in rural areas have mostly been related to concepts such as open innovation, due to the special characteristics of their implications on local societies and the inclusion of local governments to stimulate the process of local development [14].

In this process of empowerment, co-operatives take on the role of institutional entrepreneurs [15], leading collective action in support of local economic development, since their organisational characteristics are one of the main pillars of the development potential in rural spaces [16]. For some regions and activities, such as that of olive oil in some villages of Andalusia, co-operatives behave as organizations boosting not only economic results, but also especially acting as social cohesion instruments [17]. Hence, the actions taken by co-operatives are collective goods in the sense that they benefit the rural society as a whole, due to their multiplier effect on farmers and other local activities. In these sense, we can label co-operatives as commons [18] because of their cohesion capacity in rural areas where no others economic organizations exist.

1.2. The Territorial Context

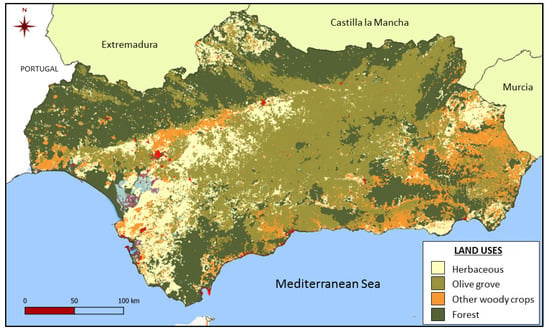

Andalusia is an exceptional case of agricultural specialisation, where 16,947 km2 of its land is dedicated to olive groves, i.e., 19.34% of its territory [19] and producing, in seasons such as 2018/2019, up to 46% of all the olive oil produced worldwide. Specifically, for this year, it produced 1.37 million tonnes out of a total of 2.96 million tonnes [20]. As can be seen in Figure 1, a monoculture has developed, which is located especially in the valley of the River Guadalquivir. The growth of the economy tied to this activity is crucial for the region, to the extent that specific legislation has been enacted. In the explanatory statement confirms that the olive producing activity “constitutes the main activity of more than three hundred Andalusian towns in which more than two hundred and fifty thousand families of olive growers live, and provides more than twenty-two million days of work per year” [21].

Figure 1.

Andalusian olive groves in the context of agricultural land use (2018). Source: Land use and land cover in Andalusia. http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/medioambiente/site/rediam.

The majority of the olive crop is used to produce oil. Most of olive groves are organised around small family farms with traditional plantations, and are characterised by the widespread phenomenon of part-time agriculture and the attachment of their owners to the land. Highly dependent on subsidies to ensure their economic viability, due to the fact that costs has been higher than the market prices during the last years [22], a large proportion of Andalusian olive growers are organised into cooperatives. Most of these take defensive manoeuvres against the vagaries of the market, but their large numbers and lack of interconnection render them rather toothless when it comes to influencing prices [23].

Co-operatives have long been reacting, to a greater or lesser extent, to the new challenges they face. Thus, it is possible to find different strategies that have emerged, either in the search for technical solutions in order to lower costs and boost harvests, or in the incorporation of qualification and diversification processes [24]. In order to deal with globalisation challenges, co-operatives have to meet the requirements of international competition. Due to their absolute implication in the daily rural life, they might constitute a key element for social cohesion and rural development.

As shown in Table 1, Spain’s accession to the European Common Market (1986) began a stage of surface area expansion (and productive intensification) of the Andalusian olive grove. The stimuli of the agricultural policy of those times were especially responded to in the provinces of Jaen, Granada, and Cordoba, where so-called intensive olive groves were developed, with plantation designs aimed at mechanising the harvesting techniques and in which irrigation became a distinctive feature of a crop that had previously been considered dry farming and designated to occupy the least fertile land. The end of the protectionist and productivist model of this common policy, from 1999 onwards, signified, among other things, the withdrawal of subsidies for new plantations and the progressive conversion of this assistance into payments decoupled from production.

Table 1.

Growth of the surface area planted with olive groves (ha) in the Andalusian provinces, from 1960–2018.

One of the responses of big farmers in Europe, and then worldwide, to this new playing field was the development of super-intensive plantations, characterised by the introduction of hundreds of trees per unit of area, as well as the adoption of straddle harvesters. The aim was to increase harvests and reduce production costs in order to make farms profitable in the absence of agricultural subsidies. This strategy has been carried out mainly in the areas with the most fertile land in the lower Guadalquivir, especially in the province of Seville, which has contributed to reduce cost, obtaining a profitable margin even in the international panorama of low prices (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Costs of production (€/kg olive oil).

However, while cooperativism forms an essential part of the organisational strategy in those areas where the oldest olive groves predominate and where the intensive olive grove emerged in the heat of the CAP in the final decades of the 20th century, these more recent advances characterised by the super-intensive plantations are far removed from the cooperative business models. On the contrary, they match the agribusiness model with similar characteristics to those that have appeared in other areas of recent olive grove expansion, with the Portuguese Alentejo region being one notable example [25]. That is the most important challenge that traditional farmers grouped into co-operatives must face [26].

The trend observed in recent years only confirms this expansion and, along with it, the coexistence of two contrasting models. In fact, while olive groves with less than 100 trees per hectare are decreasing in number, those with more than 1000 trees are only expanding, either replacing other crops or traditional olive groves. However, the overall surface area of the higher density olive groves is still limited and is concentrated in the most western part of the region (Table 3).

Table 3.

Olive grove area (ha) by province and planting framework (trees per hectare) in 2018.

1.3. The Objective of the Work

Much has been written about olive oil co-operatives in relation to their capacity for stimulating rural development [27,28,29], but, as far as we know, there is a gap in the literature about the influence of innovation processes in olive oil co-operatives as instruments for social innovation in rural areas.

Therefore, the aim of this paper is, first, to identify the innovations Andalusian olive oil co-operatives have implemented and, second, find out if these innovations could become social innovation processes stimulating socioeconomic local development in the coming years.

In order to meet these goals, emerging processes of innovation have been detected in Andalusian co-operatives of olive growers. Then, the paper attempts to answer the following question: Could these experiences be identified as social innovation processes? Then, as a consequence, are co-operatives elements of social cohesion and rural development in the region?

Effective co-operative practices would facilitate their spread to those areas where doubt still lingers about the advisability of adopting them, a situation that could be reversed with support provided by public policies. Our hypothesis is that there are already sufficient examples of social innovation to promote the renewal and improvement of the cooperative movement in relation to the challenges posed by globalisation and, in particular, the competition from new producers worldwide based on capitalist economic models without territorial anchorage.

In short, the research question that we ask ourselves is whether cooperativism, through processes of social innovation, can continue being one of the fundamental elements for the development of rural regions in Andalusia. In what follows, this work presents the materials and methods used for the research, the results found, and their analysis, ending with some conclusions on the research carried out.

2. Materials and Methods

The research was designed for the purpose of analysing innovations implemented in different parts of the region by co-operative enterprises of various sizes, dynamics, and structure. Given that there is no public information available on the municipal distribution of the production volume of olive-growing co-operatives, an express request for information was made to the State Transparency website (https://transparencia.gob.es/), which provided the information requested on the weight and local distribution of olive-growing co-operatives in Andalusia.

From the cartographic expression of the available quantitative data, it has been possible to analyse both the spatial distribution of the co-operatives in the lands of the Andalusian community and their importance in terms of production volumes. The work has been completed with a historical review of the evolution of co-operatives, based on the available literature.

A qualitative research design was created to investigate the process of incorporating innovation utilizing an interpretivist framework [30], which allows exploration of subjective values that individuals create to form their own reality interacting with others [31]. Qualitative research is a systematic and subjective approach to highlight and explain daily life experiences and to give them meaning [32]. Conceptually, individuals perceive the world differently because of their own experiences and perceptions in different contexts [33].

In-depth semi-structured interviews with the heads of co-operatives permitted exploration of the involved process of innovations. Interviewees’ recruitment was conducted using web pages, mass media advertising, technical magazines in the olive oil field, the information accumulated in previous research [24,26,34] as well as informal and non-codified information spread out in the professional environment of olive oil in Andalusia. Ten people were identified and face-to-face interviewed. Although a research limitation is the small size of the sample, the decision about when to stop conducting more interviews was made once responses became redundant, i.e., when they seemed have reached the point of saturation [35]. This number has been sufficient given the homogeneous nature of the cultural, institutional and economic environment in which the research has been carried out.

The interviewees were asked to present a strategic vision of their organisation and to describe in detail the most notable innovative initiatives being pursued, including a description of them, the motivations behind the introduction of the changes, the goals achieved, the resistance encountered, the most important lessons learned so far from the process, and the potential the initiatives offer for other cooperatives to incorporate them. Finally, the interviewees were encouraged to indicate what other types of initiatives their cooperatives could implement to strengthen their ties to the region in which they operate.

The fieldwork was carried out in the second half of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020, including visits and direct contact as well as telephone conversations for contrasting possible misleading data. The notes taken during the interviews, as well as the transcriptions of the conversations, were grouped thematically, guaranteeing the anonymity of the data. The use of content analysis allowed us to analyse and contrast them with theoretical arguments and empirical evidence, as is usually done in qualitative studies [36,37,38]. Mayring [39] defines this as a text analysis method empirically and methodologically controlled within the context of communication. Following content analytical rules and step-by-step models, without rash quantification, and the use of a deductive approach permitted data were processed to identify different categories [40].

The method used for identify social innovations leaded by co-operatives has been testing the managerial, technical or organizational innovations identified and, afterward, explore if they have provoked a change in rural society on habits, routines, ways of thinking, ideas or myths. In short, the research contrasts the innovations incorporated in olive oil co-operatives with the institutional change in the rural milieu.

3. Results

3.1. General Context

In terms of a bottom-up strategy, the first experiences of agricultural cooperativism had to do with real processes of social innovation. The origin of the olive oil cooperative movement can be traced back to the 1920s. Notwithstanding that, it was not an initiative that arose from a social movement, but from the desire of the large olive growers to defend the price of their product against the pressure of national and international intermediaries [41]. The first co-operative was created in 1929, under the name Unión de Olivicultores de Jaén. It was given a top-down organisational structure by the state government, within the initial approach being territorial groupings at various levels, thereby allowing the supply of Spanish olive oil to be concentrated, in an attempt to improve margins and reduce the costs of the marketing process [42]. This initiative failed in the 1930s due to mismanagement, the poor handling of the international crisis, and because of difficulties in accessing markets by some actors who had no experience or capacity to carry out the mission they had been entrusted with [43]. In the 1960s, the idea of co-operative territorial unions in Spain was revived with the same top-down approach, but ended up failing in the 1980s under accusations of mismanagement and corruption [41]. With the outbreak of the civil war in Spain, agricultural collectivisation processes were carried out in the province of Jaen, which represented the first steps of social-based cooperativism in the cultivation of olives [41]. Once the war was over, these experiences were abandoned, but in the following years, from a radically different perspective, farmers organised themselves into cooperatives to avoid the pressure that oil manufacturers exerted on the price of olives. Thus, they began to create their own oil mills to process the fruit under a cooperative system [44], which led farmers to manage the next link in the production chain, becoming olive oil producers, and to a form of empowerment they had heretofore lacked [45]. Since the second half of the 20th century, olive oil cooperatives have been the basis of the local economy in most small and medium-sized municipalities in the interior of Andalusia [46].

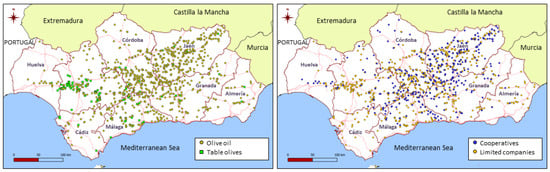

The cooperative model created from a bottom-up perspective has proved to be very useful to maintain and boost the income of olive growers in Andalusia. From its beginnings in the middle of the last century to the first years of the 21st century, advances in the cooperative process have been carried out to meet the challenges of globalisation. The result has been a more concentrated supply of olive oil, to increase the role of co-operatives in the global value chain, giving rise to the constitution of second-tier entities [47]. Good examples are the cases of DCOOP, JAENCOOP or OLEOESTEPA, whose turnover is more than 40% of the total co-operative mills. Today, olive oil co-operatives are more than 85% of the total agrarian co-operatives in Andalusia (see Table 4), leading the most important activity for most of rural towns in the region (Figure 2), with a turnover of more than € 3900 million in 2018.

Table 4.

Comparison between agrarian co-operatives and olive oil co-operatives in Andalusia (2020).

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of olive oil mills and olive packaging plants and their classification according to their business model (2020). Source: Andalusian Register of Agrifood Industries (GRIA) http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/gria/.

Grouping the oil mills and the plants for curing and packaging table olives together (Figure 2), there are 1315 industrial entities, of which 499 can be said to either follow cooperative models (457) or be involved in joint ownership arrangements or agrarian processing societies (42). Although the capitalist models are more numerous (816), their average size is much smaller, as shown by the fact that the cooperatives process 70% of the oil; moreover, cooperatives are the main players in the provinces where the most traditional olive groves predominate, as is paradigmatically the case in Jaen (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of olive oil production by province and by type of business model in Andalusia during the 2018/2019 agricultural season.

Table 6 shows average data of co-operatives participating in the research in relation to average data of olive oil co-operatives in Andalusia.

Table 6.

Characterisation of co-operatives selected and Andalusian ones. Average data.

Selected innovative co-operatives show some characteristics that distinguish them from the others. Firstly, the number of members is quite higher than the average of Andalusian co-operatives. Secondly, the members, in average, are small farmers. They have less than half of the hectare of Andalusian farmers do. Thirdly, despite the farmers’ average age is similar, those below their forties are rather more numerous. Fourthly, women members are slightly more. Fifthly, while almost two thirds of Andalusian olive growers have a main activity out of agriculture, in the selected co-operatives the figure is higher, more than three quarter.

Being small farmers and with other main activity, co-operatives offers them the possibility to render a part-time agriculture under efficiency criteria. Being entities with a high number of members, give innovation initiatives opportunities to raise. Besides, being young farmers, the innovation initiatives are easier to render. Finally, a high proportion of women could affect the intention of changing more than in other co-operatives.

3.2. Pervasive Problems

Notwithstanding that, despite the fact that the aforementioned characteristics concede advantages for innovation to emerge, co-operatives in the rural Andalusian territory share some myths about working in fields hampering the innovation processes. Thus, among the difficulties that the interviewees foresee in the medium term for the future, one of the most worrisome is the lack of generational change when it comes to taking over the reins of the agricultural operations and the management of the cooperatives themselves. This was expressed by the manager of one of the co-operatives in one of the interviews conducted:

- “I don’t see a governing board in the future. There are no young people who might be interested in taking over.”

In this regard, the children or grandchildren of the founders of these social economy enterprises respond to a very different mentality and time. If the older members accepted the long waiting periods between the delivery of the product and receiving payment, the younger ones do not do so willingly. Moreover, since for many of them agriculture is no longer their main source of income, they are losing their emotional and economic ties to the cooperative. Thus, it is becoming common for members to leave the co-operative or, flouting the rules of the co-operative, sell part of their harvest to industrial producers who pay for it when it is purchased or later at the seller’s convenience.

It should be borne in mind that it was, precisely, the pressure exerted by the mill-owners on olive prices that gave rise to the creation of the olive oil co-operatives in the thirties of the last century, which we have qualified as a process of social innovation. If the non-co-operatives mill-owners have now adapted better to the context and are able to respond more quickly to the needs of the olive growers, the situation could see itself reversed in the long term, and this is one of the great threats facing the cooperative model.

Another common problem, and in spite of the cases of concentration, is business atomization and the small size of the business units in olive co-operatives. This is especially problematic taking into account that a large part of the business is international in nature and that the technical and organisational capacities for export require defined professional specialisation if the business opportunities are to be taken advantage of.

The internal problems faced by these organisations are numerous and recurrent. There is a lack of transparency and internal communication, some resistances and suspicions that the most dynamic technicians have to face in a panorama dominated by a lack of professionalisation. Several of the interviewees have drawn attention to decision-making by the owners of the business without providing the slightest business culture, as well as the slowness or immobility in making decisions.

3.3. Innovations

As it is well known, rural societies are reluctant to change. Then, the processes of innovation are slow, due to the initial reticence of farmers to introduce new ways of managing, investing on new activities or marketing their products. However, currently, this reticent position is starting to turn into a more proactive one. Using a strategy of wait-and-see, some co-operatives are incorporating innovations that have already demonstrated successful results. This process is typical in environments where slow innovation prevails, stimulating social responses to the dynamic markets where co-operatives are now competing in order to meet their challenges.

Table 7 groups the main innovations carried out by the co-operatives interviewed into four models and three categories of innovations: management, technical and market, and their effects on traditional farming. Furthermore, it classifies the intensity of resistance and the impact the implemented actions are having on rural society. Finally, it presents the capacity of these changes to stimulate social innovation.

Table 7.

Main innovations, impacts, resistances, effects, and potential for social innovations in olive oil co-operatives.

Model 1 is for entities incorporating management and technical changes that have not found stiff resistance from the rural society. Model 2 and 4 presents the management and technical changes that have had to overcome a profound opposition before to be implemented. Finally, model 3 is for innovations well accepted by rural society as a whole, incorporating changes in all of the spheres of innovation but not affecting traditional ways of farming.

Over the last 40 years, the most important issue that have contributed to change rural society has been, undoubtedly, the quest for quality, in order to put in the market a differentiated product. There has been a longstanding desire to improve the commercialisation and control of more links in the olive oil value chain. The consensus has always been that it is impossible to improve the commercialisation without first maximising the quality of the product. Thus, the improvement in quality is one of the mantras that has driven the olive growing activity in Andalusia since the final decades of the 20th century—which has led to the appearance of some territorial brands. To achieving this goal, the cooperatives have carried out technical innovation processes, investing large sums of money in the modernisation of the industrial facilities and in the organisation of the oil mills during the harvesting season. In this way, the quality of the product has improved and the earnings of the cooperatives have grown.

In order to reward those members who make the greatest effort to obtain a higher quality product, model 3 co-operatives have been taking measures such as remunerating the producer for the olives from the tree or from the ground in different ways or, more recently, using a thorough classification in order to reflect the differences in the product delivered by each of the harvesters. An example of this is Picualia, where they use a global quality index, although from an organisational point of view, the entity that stands out the most is San Sebastian, the co-operative of Benalúa de las Villas (Granada) [48]. There, the olives received must be inspected twice before being processed. At the entrance of the mill, the first inspector, called veedor, takes note of the quality parameter of the product, using an electronic device to link the product reception to the number plate of the vehicle. Once the data has been charged in the electronic platform, the system indicates what delivery point the farmer must download the olives in. Furthermore, before the olives are put into the mill, a second inspector makes a security check.

The manager expressed the following:

- “Think about it, why all the farmers must earn the same money if some of them bring the olives plenty of mud and others bring the fruit completely clean?”

- “The differences in price between the worst and the best olives can range, depend on the season, from 20 to 80 cents per kilo.”

These innovations have been welcomed for the farmers, but they have not implicated a change in social behaviour, apart from stimulating an increase in the quality of olive oil.

Model 4 co-operatives have introduced changes related to obtaining an early-harvest olive oil, which is valued in the market much more. It has resulted in an innovation in the conception of agricultural work, which has been transferred to the entire rural society. This new idea has led to the generalisation of the practice of obtaining batches of the highest quality oil to be bottled and marketed directly at the oil mill to be sold on the national and international market, an action that has been reinforced by the awarding of prizes in national and international competitions. In this case, the incorporation of a new way of harvesting have challenged the traditional conception of rural society about efficiency, costs and market, leading co-operatives to create different “mini-seasons” in mills. After years of a stiff opposition—some farmers considered early harvesting as a madness [34]—now this action has been standardized, changing the dynamic of rural society for obtaining an extremely high quality olive oil, and making emerge a shared feeling of pride [49]. The social trust that has been triggered with this process allowed to unleash a potential of receptiveness to innovations in different aspects such as new services.

Under a strategy of differentiation, model 2 co-operatives have opted for obtaining organic olive oil. Such decision has implied fundamental changes in some villages. In cases like this, the introduction of innovations can create conflicts. The case of SCA Sierra de Génave is a good example, the conflict arose when a group of young farmers proposed to the general assembly that the co-operative should support their farmers in the transition to organic farming. Local tensions were increasing, because the more traditional farmers were reluctant to incorporate such change. After a period of discussion, the most innovative farmers splitting down the co-operative to create the first organic olive oil in the territory. Now, a social process of change is inspiring young farmers to turn their traditional activity into a more sustainable one contributing to achieving global goals.

Traditionally, in addition to concentrating supply and milling the fruit to obtain the oil, cooperatives have provided other services to their members. These range from the opening of fuel stations for the exclusive use of the members at reduced prices, the existence of consumer cooperative shops that supply inputs in order to reduce costs, to the offering of financial services—as in the case of credit unions. These first services (fuel, consumer stores, and credit unions) brought about important innovations in the rural areas of Andalusia during the second half of the 20th century. However, today, they can be considered as having been widely adopted and are well embedded in local societies. This is the case of model 1 co-operatives, but now, once new ways of meeting the challenges of the market are being applied, new innovation in services are appearing. The most important are the performance of farming tasks through shared management, and even the restructuring or reconversion of the cultivated lands with the advice and support of the cooperative (model 4).

Shared management and restructuring processes are particularly innovative today. Both are part of the response of Andalusian cooperativism to the challenges of the globalisation of cultivation [23]. The solutions that they offer aim to tackle the structural problems of land ownership distribution, such as smallholdings, the fragmentation of plots and the dispersion of ownership, as well as the lack of generational turnover in the countryside.

One of the best examples for co-operatives using shared management of tasks is SCA San Roque of Arjonilla in the province of Jaen. It is made up of 1125 members, whose combined lands total about 5000 hectares, having an average production of about 20 million kg of olives per season. Members are elderly farmers, aged 60 or more, and they have an average farm size of five hectares. The governing council of the cooperative noted that for a time some farmers were abandoning the activity temporarily or definitively, because its cost exceeded their total income including subsidies. Faced with this situation, the cooperative has facilitated the grouping of neighbouring landowners, a formula that allows for cost savings [50] and the transformation of unpaid work into skilled employment in the locality [51]. This action opens up opportunities for young people to get into farm activity and keeping the land cultivated. The consequences of activating this action could be one of the main pillars for fighting against depopulation in rural areas and maintaining the rural landscape.

In the case of farm management for the transition towards crop restructuring, the same cooperative has carried out a pioneering experiment, which has consisted in restructuring 43 hectares into intensive (41 hectares) and super-intensive (two hectares) olive groves. The main innovation in this regard is not so much the implementation of the process, which is a technical matter, but to incorporate a new system of farming. The manager and the governing council have had to overcome the difficulties the rural community arose to adopt new institutions. Most of them consisted in convincing a very traditional community of the need to improve production efficiency in a context of growing competitive pressure. Despite the difficulties of implementation, this experience has been possible thanks to a specific action of the Rural Development Programme of Andalucía, through an experience of working together with other stakeholder within the territory, such as regional government, local actors and universities grouped under a regional project of rural innovation and development.

Innovations in management have introduced changes in the relationship between the co-operatives and the rural society as a whole. From the perspective of the social responsibility of the co-operative entity towards the region, beyond the support to social and cultural entities or the adoption of gender equality policies, scholarships are offered to the children of members, dual professional training opportunities are made available to members and support is given towards research initiatives, since some co-operatives have been integrated into R+D+i projects with public entities and universities. In the environmental field, actions are carried out to close the ecological cycle of the activity—such as the generation of energy from pruned branches— or the development of olive oil tourism and environmental education activities.

The relevance of the innovation process as a catalyst lies with the managers of the cooperatives who, through their leadership, behave as real policy entrepreneurs [52], and some cooperative presidents, who are looking at promoting new social innovation initiatives that go beyond the productive life of their members. An example is the idea about the planning of nursing homes, which, although still under discussion, is very interesting as it illustrates the social innovation processes that could be generated in such a traditional area as rural Andalusia.

4. Discussion

The research carried out has shown that social innovations are not a novelty in the Andalusian rural environment, not even in terms of cooperativism. Even the objectives that were set 100 years ago are still valid. The interviews conducted have also revealed the difficulties faced by the cooperative model in an increasingly interconnected and professionalised competitive framework. However, it is important to note that a rediscovery of the social economy as a source of social innovation processes is taking place in the academic discussion [53].

In reality, despite the progress made, management problems remain and the demands on the support for public aid continue unabated. This activity finds it difficult to see itself competing in the international market, having become accustomed to operating under the protective umbrella of the State, within the framework of the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy.

This traditional conception of the productive activity is still deeply rooted in cooperativism. Once this became the business model in rural Andalusia, and the farmers stopped being olive sellers and became olive oil sellers, the idea took hold among farmers that their work ends with the delivery of the product to the oil mill, believing that the cooperative is the market and not a means to reach it [54]. This has led some of the most innovative farmers with sufficient production capacity to consider leaving the cooperative to start an independent business.

In this regard, we can highlight that when initiatives for change are carried out from a bottom-up perspective, they are more likely to take hold than when they emerge from a top–down approach. The processes of social innovation that have generated the greatest impact in the rural area of Andalusia confirm this, such as the early-harvesting and the new practices in farming searching for improving the quality of the final product, since they are supported by the pre-existing social networks in the region fundamentally anchored in the territory by the co-operatives [55]. This assertion is also in agreement with the results of other international studies that focus on the success of social innovation processes when they are carried out from a bottom-up perspective [56].

The reasons for this are based on the fact that the strategic change initiatives carried out in the region must be in line with its institutional framework. Accordingly, informal institutions are key when it comes to shaping a positive outcome from the changes implemented so that they become real processes of social innovation that last over time and contribute to improving the quality of life of citizens in rural areas. In fact, cooperatives have become institutional entrepreneurs [15]. Being labelled by local society as “commons”, as opposed to the other mills, which are described as “private”, co-operatives become crucial factors for collective action [57]. The efficiency of community co-governance, the shared feeling of the creation of value [58] and the reduction of costs in the generation of social networks [59] contribute to the emergence of increased earnings in the region.

This territorial conception of cooperatives makes them a social reference inseparable from the rest of rural society, which means that any innovation carried out in them could be seen as a social innovation. From this perspective, the cooperative becomes an agent of territorial transformation [60], due to the impact any action taken by them has in rural society life. In this context, participatory governance makes them agents that allow for a more inclusive political process, integrating the needs of groups that were more marginalised in the past, and which by becoming empowered now manage to better address their previously unsatisfied needs [5].

However, beyond the large number, size, industrial capacity or great potential that cooperatives have for rural development [27,28,29], dynamism and innovation are not exactly the most distinctive characteristics of these social economy enterprises in the rural sphere [61].

As the results have showed, only a very reduced part of innovations rendered in olive oil co-operatives could be considered as social innovations, and even in these cases, they are only starting to be developed. These are the processes facing more resistance to change probably because they are related to inherited routines of farming.

Then, for social innovation processes to appear, the position of leading innovators is crucial, given that through the demonstration effect they have managed to consolidate and spread the proposed institutional changes throughout the region. The processes of social innovation also require sufficient institutional flexibility to permit the incorporation of new rules that guarantee property rights and the participation of new actors in the market. In harmony with local culture, the so-called processes of slow innovation could allow the adaptation of changes within the institutional structure of the territory, without producing serious social disruptions, which could support the incipient processes of social innovations to consolidate. In this regard, given the fact that social innovation processes have inherently political dimensions [6], with the participation of different public and private bodies, there are only a few examples that could be considered candidates for social innovations to emerge.

Notwithstanding that, the conducted research has identified the participation of different actors in the process of innovation carried out by Andalusian co-operatives. This fact could lay the foundation stone of social innovation processes, since they can be characterised within the concept of open innovations, in the sense that they have appeared not internally in the co-operative, but in collaboration with the local society. In these processes, co-operatives make a function of territorial coordinator of the mechanisms of collective intelligence through their participation in responding to the needs of rural society.

In a region such as rural Andalusia, where incipient signs of depopulation are appearing, social innovations tied to traditional agricultural activities could be a key element in preventing the growth of this trend and contributing to the improvement of the living conditions of rural inhabitants through an increase in the competitive capacities of endogenous development activities. To this end, the literature on social innovations has proved that there are opportunities for change when considering the six dimensions required by empowerment processes: relatedness, autonomy, competence, impact, meaning, and resilience [62,63]. In this regard, some innovations that are emerging in the olive oil co-operatives interviewed could meet them if they have time to develop the necessary impact and, afterwards, spreading in the rural society.

Social innovations take many forms, appearing as new institutions, social movements, new practices or different collaborative structures [2]. It is in this last category that we can place the most recent innovation processes carried out by olive oil cooperatives in Andalusia, as they are directed towards improving efficiency in the management of agricultural work, which will result in cost reductions. This is a key element for the survival of the traditional activity in the region, since the average profit margin for small and medium-sized farmers has fallen in recent years, with losses in the last two harvests.

The incorporation of new technologies for agricultural management, the obtainment of higher quality products and the improvement in efficiency in the management of the value chain are objectives that the most innovative managers of cooperatives are trying to incorporate into the productive activity. In any case, the success of these goals depends on training processes being maintained and strengthened among the youngest farmers, whose numbers are lacking due to the allure of urban activities compared to life in the rural environment.

5. Conclusions

The importance of cooperativism lies in the fact that individual farmers, except for the very large ones, are not able to build up the value of their products or defend them against large-scale distribution networks, nor can they join the new wave of technological change in the digital revolution that the whole food chain is experiencing [64]. Therefore, cooperatives are the appropriate instruments for working in the market, but they need to incorporate technological, organizational, and social innovations that allow them to compete with other regions while maintaining the standard of living of the societies where they carry out their activity.

It is clear that if the maintenance and expansion of the olive-growing activity in Andalusia is to be achieved, it will require sufficiently strong processes of social innovation to resist the magnetic pull that cities exert on rural areas, which siphon off the very people that have the capacity to incorporate management, production and marketing innovations in the olive-growing activity. In this way, Andalusian rural society can contribute to a reduction in the social and regional inequalities that are beginning to entrench themselves in Europe. In this regard, cooperatives and their social innovations could contribute to anchoring the population to the land [65]. Not in vain, traditional agriculture has a human dimension, it is the backbone of the territory, it is anchored in rural towns, and it is more environmentally sustainable than capital-intensive agriculture.

The processes of social innovation that are beginning to emerge in Andalusian olive oil cooperatives can contribute to making collective organisation competitive in an open market economy, within the global production chains, which would signify an enormous capacity for transformation from the bases of rural Andalusian society [66].

Co-operatives are elements of resilience that provide cushioning for members during critical situations. Clearly, one of the main objectives of the co-operatives is to shield small farmers, which means that they act as a type of guarantee for the local economy. Thus, the operation of the cooperative is not designed to take risks, reducing the fatal consequences of high exposure in times of crisis [34], but at the same time, they are inflexible structures that perform far below their true potential.

Is in this primary role of protecting the local economy where co-operatives are key elements within the processes of social innovation. They are necessary to stimulate the changes that will make rural societies able to compete in the market and turn them into territories that can effectively meet the objectives of sustainable development as decreed by the United Nations.

The countries of the European Union have understood that the promotion and encouragement of co-operatives is important for regional development in its three aspects—economic, social, and environmental—to which the processes of empowerment and social innovation that they foster in rural areas make a decisive contribution [67].

This paper has shown that olive oil co-operatives have the opportunity to boost social innovation processes in Andalusian rural society. Innovative actions like the paper presents could allow local farmers to adapt to the market and contribute to the improvement of their living conditions, thereby maintaining the rural environment with productive and social activity and helping to curb the expansion of the processes of depopulation within those regions with the greatest agricultural presence. In order to make better use of the synergies of these initiatives, it would be smart to develop public policies to support them, so that the processes of social innovation through cooperativism ensure their success and consolidation. All this will also contribute to the reduction of social and territorial inequalities in Europe.

This research is a tentative approach to the comprehension of the social innovation processes in the Andalusian rural society. In this regard, the paper presents some limitations about the consolidation of these processes, which are now only starting to emerge. In the future, investigations are needed to corroborate the success of the initiatives and the implications for rural development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.S-M., J.C.R.-C., and V.J.G.-S.; methodology, J.D.S.-M., J.C.R.-C., and A.G.-A.; software, A.G.-A.; validation, A.G.-A.; investigation, J.D.S.-M., J.C.R.-C., A.G.-A., and V.J.G.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.S.-M. and J.C.R.-C.; writing—review and editing, J.D.S.-M. and J.C.R.-C.; funding acquisition, J.D.S.-M. and J.C.R.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the University of Jaen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Noya, A. The Essential Perspectives of Innovation: The OECD LEED Forum on Social Innovations. In Fostering Innovation to Address Social Challenges; OECD, Ed.; OECD: Paris, France, 2011; pp. 18–24. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/sti/inno/47861327.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Cajaiba-Santana, G. Social innovation: Moving the field forward. A conceptual framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2014, 82, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Economic performance through time. Am. Econ. Rev. 1994, 84, 359–368. [Google Scholar]

- Eichler, G.M.; Schawarz, E.J. What Sustainable Development Goals Do Social Innovations Address? A Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Social Innovation Literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.; Morgan, K.; Richardson, R. Social innovation in question: The theoretical and practical implications of a contested concept. Environ. Plan. C: Politics Space 2018, 36, 496–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayob, N.; Teasdale, S.; Fagan, K. How Social Innovation “Came to Be”: Tracing the Evolution of a Contested Concept. J. Soc. Policy 2016, 45, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, H. Social innovation and citizen movements. Futures 1993, 25, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabel, C. Ireland. Local Partnertships and Social Innovation; OECD: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mumford, M.D. Social Innovation: Ten Cases from Benjamin Franklin. Creativity Res. J. 2002, 14, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phils, J.A.; Deiglmeier, K.; Miller, F.T. Rediscovering Social Innovation. Stanf. Soc. Innov. Rev. 2008, 6, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; Nussbaumer, J. The social region: Beyond the Territorial Dynamics of the Learning Economy. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2005, 12, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H. Slow innovation in Europe’s peripheral regions: Innovation beyond acceleration. Schlüsselakteure Reg. Welche Perspekt. Bietet Entrep. Ländliche Räume 2020, 51, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Barquero, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. Local development in a global world: Challenges and opportunities. Reg. Sci. Policy and Pract. 2019, 11, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leick, B. Institutional entrepreneurs as change agents in rural-peripheral regions? ISR-Forsch. 2020, 49, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mozas, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. La Economía Social: Agente de cambio estructural en el ámbito rural. Rev. Desarro. Rural Coop. Agrar. 2000, 4, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mooney, P.H. Democratizing rural economy: Institutional friction, sustainable struggle and the cooperative movement. Rural. Sociol. 2004, 69, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Agencia de Gestión Agraria y Pesquera de Andalucía. Densidad de Plantación de Olivar. ESYRCE (serie 2015–2018); Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Olive Oil Council. Olive Oils Production. 2019. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NEWSLETTER_144_ENGLISH.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Junta de Andalucía. Ley del Olivar de Andalucía; Official Bulletin from the Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penco Valenzuela, J.M. Aproximación a los Costes del Cultivo del Olivo; AEMO: Córdoba, Spain, 2020; Available online: https://www.aemo.es/blog/noticias-aemo-1/post/aemo-actualiza-a-2020-su-estudio-de-costes-del-cultivo-del-olivo-183 (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- García Azcárate, T.; Langreo Navarro, A. Cooperativismo Agrario, Grande o Pequeño? Alternativas Económicas 2018. May, El Diario.es. Available online: https://www.eldiario.es/alternativaseconomicas/Cooperativismoagrariograndepequeno_6_776282385.htmh (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Rodríguez Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez Martínez, J.D.; Garrido Almonacid, A. Strategic responses of the European olive-growing territories to the challenge of globalization. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2261–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Martínez, J.; Gallego Simón, V. Olivares de alta densidad alentejanos y olivares tradicionales andaluces: Un análisis comparado. In Respuestas de la Geografía Ibérica a la Crisis Actual; Royé, D., Aldrey Vázquez, J.A., Pazos Otón, M., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.-J., Díaz, M.V., Eds.; Meubook: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2012; pp. 1509–1518. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Gallego Simón, V.J. Olive crops and rural development: Capital, knowledge and tradition. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso Logroño, P.; Bautista Puig, N. La significación de las cooperativas agrarias en desarrollo del medio rural: El caso de Guissona. In Proceedings of the Coloquio Ibérico de Geografía, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 24–26 October 2012; pp. 1334–1344. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322357515_La_significacion_de_las_cooperativas_agrarias_en_el_desarrollo_del_medio_rural_el_caso_de_Guissona (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Montero Aparicio, A. La Economía social y su Participación en el Desarrollo Rural; Fundación Alternativas: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Puentes Poyatos, R.; Velasco Gámez, M.M. Importancia de las sociedades cooperativas como medio para contribuir al desarrollo económico, social y medioambiental, de forma sostenible y responsable. Revesco 2009, 99, 104–129. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carson, D.; Gilmore, A.; Perry, C.; Gronhaug, K. Qualitative Marketing Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, N.; Grove, S.K. The Practice of Nursing Research: Appraisal, Synthesis and Generation of Evidence; Elsevier: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.H. Qualitative research method—phenomenology. Asian Soc. Sci. 2014, 10, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez Martínez, J.D.; Gallego Simón, V.J. The upgrading strategy of olive oil producers in Southern Spain: Origin, development and constraints. Rural. Soc. 2017, 26, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory. Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine Transaction: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Berelson, B. Content analysis in Communication Research; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Pool, J. Trends in Content Analysis; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, Champaign, IL, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, J. Qualitative Research Design. An Interactive Approach; Sage: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 2020, 1. Available online: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0002204 (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken; Deutscher Studien Verlar: Weinheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido González, L. Olivar y Cultura del Aceite en la Historia de Jaén; Instituto de Estudios Giennenses: Jaén, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gascón y Mirámón, A. Venta de los Aceites Españoles; Universidad de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 2013; Facsimile Edition of the Originals Printed in 1928 and 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Armenteros, S. Los olivicultores andaluces ante la comercialización. El caso de la “Cooperativa Nacional de Productores de Aceite de Oliva Puro” (1925–1932). Rev. Estud. Reg. 2007, 79, 73–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Armenteros, S. El Crecimiento Económico en una Región Atrasada, Jaén, 1850-1930; Diputación Provincial de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas Moral, A. Organización y Gestión de las Almazaras Cooperativas: Un Estudio Empírico; Consejería de Trabajo e Industria de la Junta de Andalucía: Seville, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Cohard, J.C. Desarrollo Endógeno en la Región Urbana de Jaén. Análisis Competitivo y Dinámico de los Sistemas Productivos Locales; Diputación Provincial de Jaén: Jaén, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas Moral, A.; Guzmán Vico, A. La evolución del cooperativismo oleícola. Integración y cooperación. In Economía y comercialización de los aceites de oliva. In Factores y Perspectivas para el Liderazgo Español del Mercado Global; Gómez-Limón, J.A., Parras Rosa, M., Eds.; Cajamar Caja Rural: Almería, Spain, 2018; pp. 107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas Moral, A.; Parras Rosa, M. Liquidando la Aceituna en Función de su Calidad: Estudio de Caso de la Sociedad Cooperativa San Sebastián Conde de Benalúa; Instituto de Estudios Giennenses: Jaén, Spain, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Farré Ribes, M.; Lozano Cabedo, C.; Aguilar Criado, E. La ‘nueva cultura del aceite’ como eje de transformación en los territorios olivareros andaluces. Rev. Antropol. Iberoam. 2020, 15, 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, S.; Perujo-Villanueva, M.; Ruz-Carmona, A. Is bigger better? Evidence from olive-grove farms in Andalusia. Acta Hortic 2018, 1199, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, S.; Sánchez Martínez, J.D.; Perujo Villanueva, M. The trade-offs between economic efficiency and job creation in olive grove smallholding. Land Use Policy 2020, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, J.W. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies; Little, Brown & Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B.; Moulaert, F.; Hulgard, L.; Handouch, A. Social innovation research: A new stage in innovation analysis? In The International Handbook on Social Innovation; Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., Hamdouch, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; pp. 110–130. [Google Scholar]

- Parras Rosa, M. El papel del cooperativismo agroalimentario como dinamizador de los espacios rurales. In Proceedings of the III Congress of Cátedra Blas Infante, Andújar, Jaén, Spain, 11 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez Barquero, A. Reflexiones teóricas sobre la relación entre desarrollo endógeno y economía social. Rev. Iberoam. Econ. Solidar. Innovación Socioecológica 2018, 1, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Repo, P.; Matschoss, K. Social Innovation for Sustainability Challenges. Sustainability 2020, 12, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Constituting social capital and collective action. J. Theor. Politics 1994, 6, 527–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, R.M. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bijman, J.; Muradian, R.; Cechin, A. Agricultural cooperatives and value chain coordination. In Value Chains, Social Inclusion and Economic Development: Contrasting Theories and Realities; Helmsing, A.H.J.B., Vellema, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 82–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Lim, U. Social Enterprise as a Catalyst for Sustainable Local and Regional Development. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Rebelo, J.; Leal, C.T.; Teixeira, A. Management and financial performance of agricultural cooperatives: A case of Portuguese olive oil cooperatives. Revesco 2017, 123, 225–249. [Google Scholar]

- Haxeltine, A.; Pel, B.; Wittmayer, J.; Dumitru, A.; Kemp, R.; Avelino, F. Building a middle-range theory of transformative social innovation: Theoretical pitfalls and methodological responses. Eur. Public Soc. Innov. Rev. 2017, 2, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, F.; Dumitru, A.; Cipolla, C.; Kunze, I.; Wittmayer, J. Translocal empowerment in transformative social innovation networks. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 955–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, M.; Kirova, M.; Soma, K.; Bogaardt, M.-J.; Poppe, K.; Thurston, C.; Monfort Belles, C.; Wolfert, S.; Beers, G.; Urdu, D. Research for AGRI Committee—Impacts of the Digital Economy on the Food-Chain and the CAP; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2019/629192/IPOL_STU(2019)629192_EN.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2020).

- Valiente Palma, L. Podría estar contribuyendo el cooperativismo a fijar la población en el territorio de Andalucía? Ciriec-España 2019, 97, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.; Partidário, M. Mind the Gap: The Potential Transformative Capacity of Social Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R. Public Policies and Social Economy in Spain and Europe. Ciriec-España 2008, 62, 35–60. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).