Gendered Roles in Agrarian Transition: A Study of Lowland Rice Farming in Lao PDR

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the differences, if any, between how men and women choose to adopt new technology?

- What are the differences between men and women, if any, in strategies and attitudes to farming and related activities?

- What are the differences between men and women, if any, in the ability to generate income and engage with farming markets?

2. Gendered Economic Transition in Lao PDR

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Data

3.2. Choice of Participants and Survey Administration

3.3. Analysis of Survey Data

4. Results

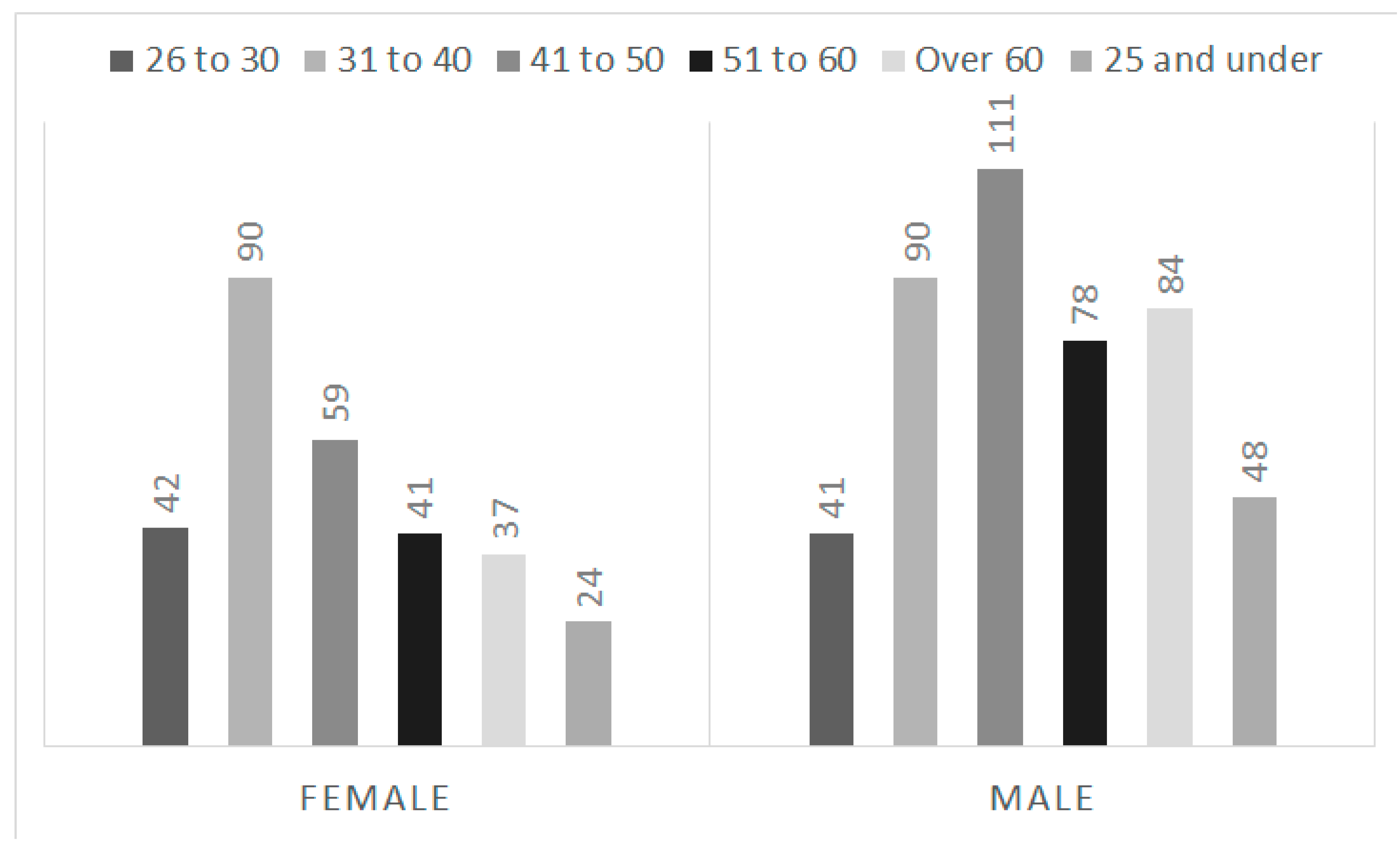

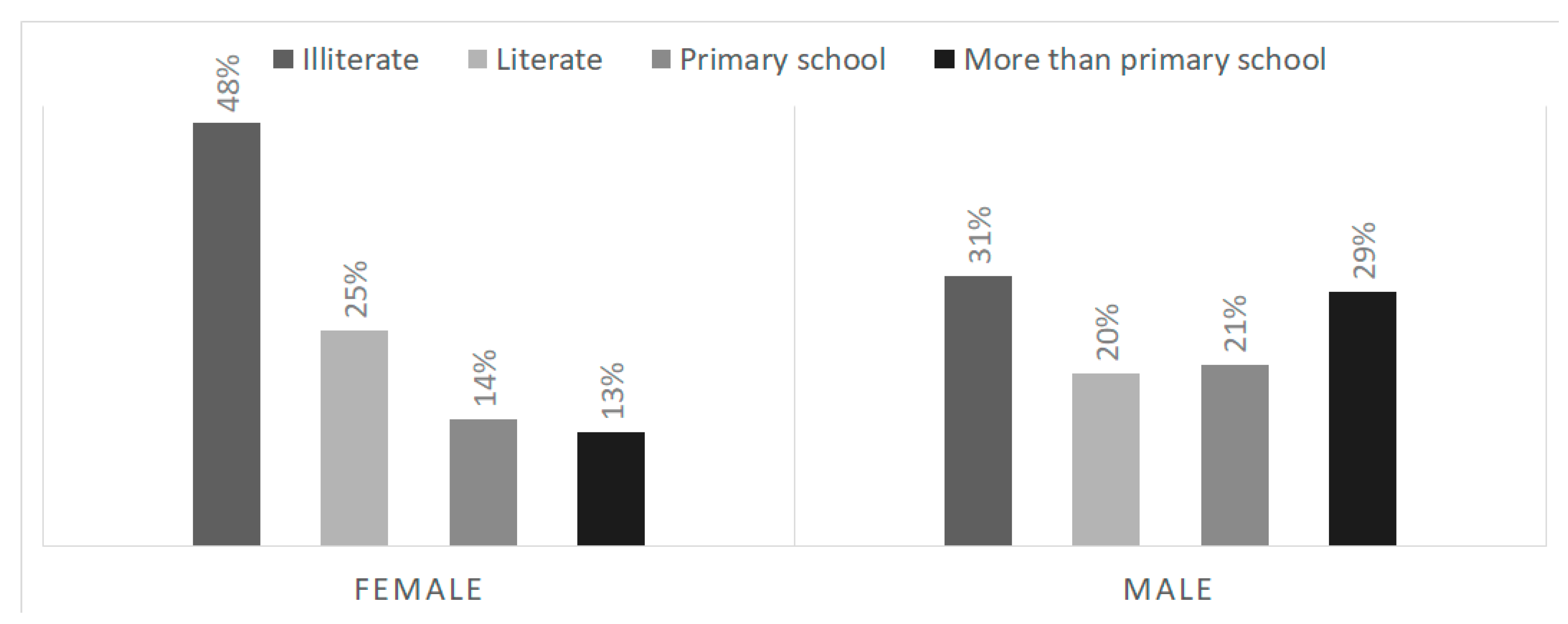

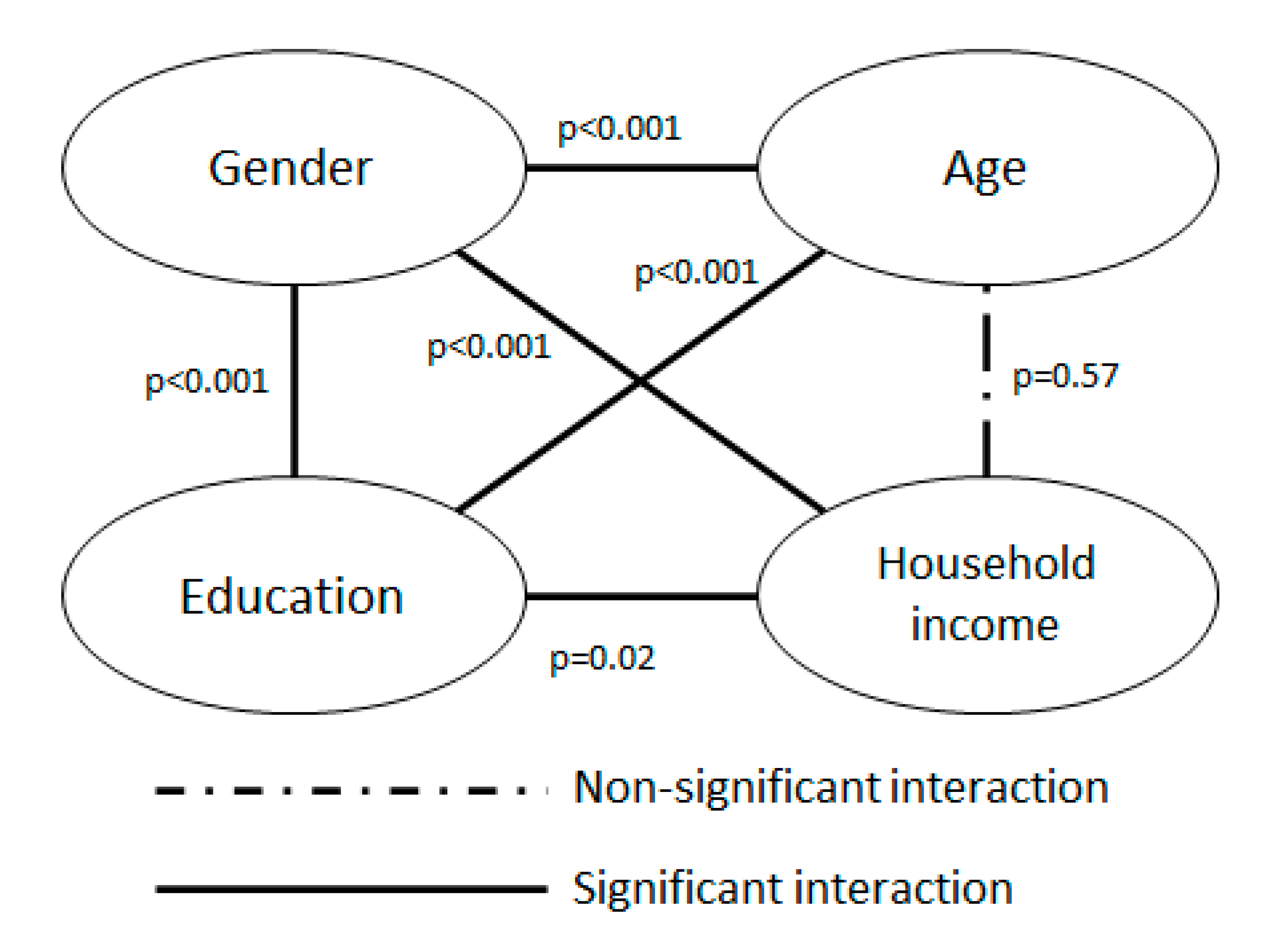

4.1. Gender-Related Differences in Age and Educational Level

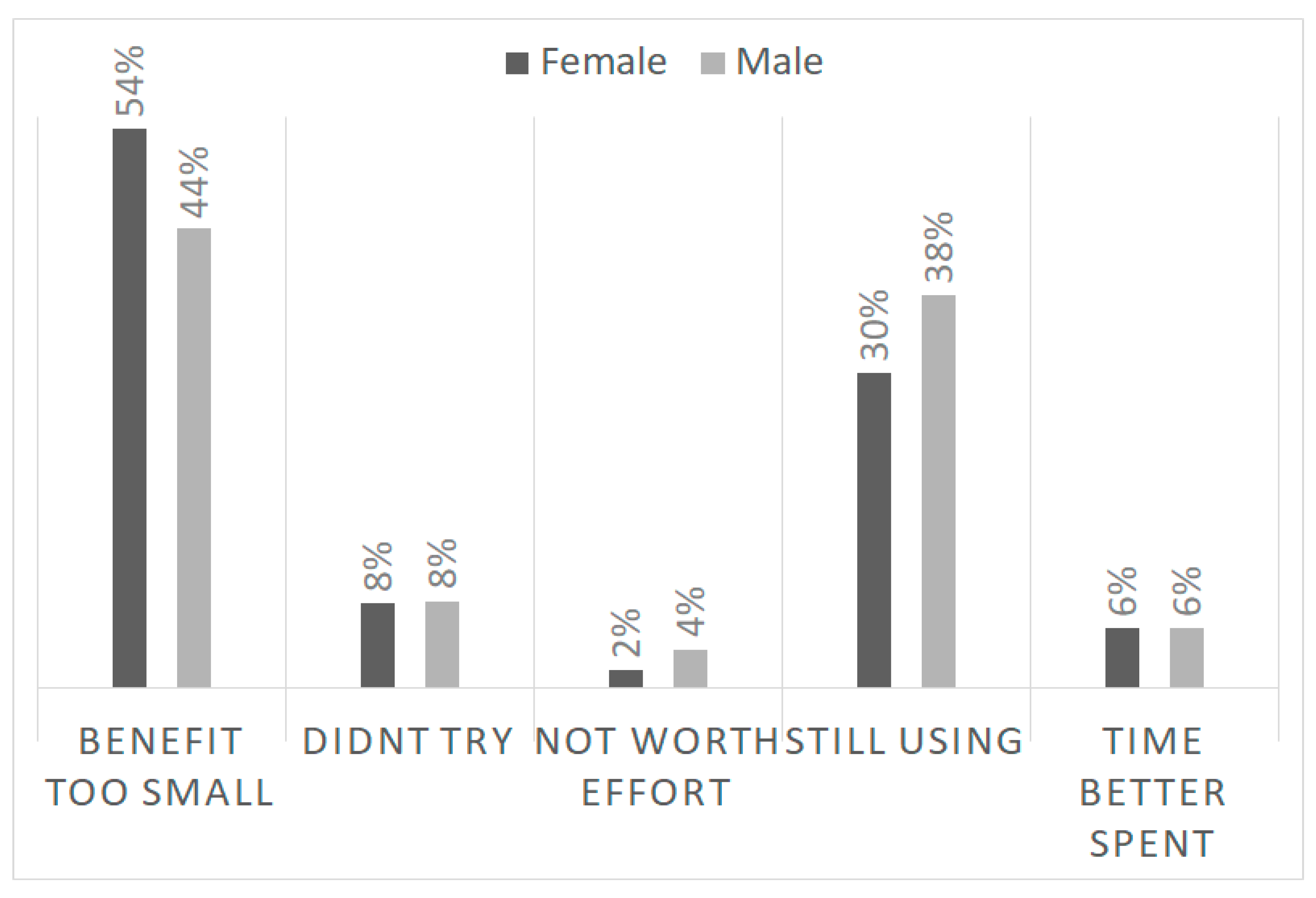

4.2. Gender-Related Differences in the Embrace of New Practices

- Men tended to adopt more new practices, but this difference was not statistically significant.

- Women tended to participate more often in trials of new practices, but this difference was not statistically significant.

- Women who adopted new practices more often reported that the adopted practices were useful, and this difference was statistically significant.

- Women who adopted new practices tended to adopt more practices than men, and this difference was statistically significant.

- A total of 17% of women who adopted new practices compared with 11% of male adopters reported to have entirely abandoned all their new practices, and this difference was statistically significant.

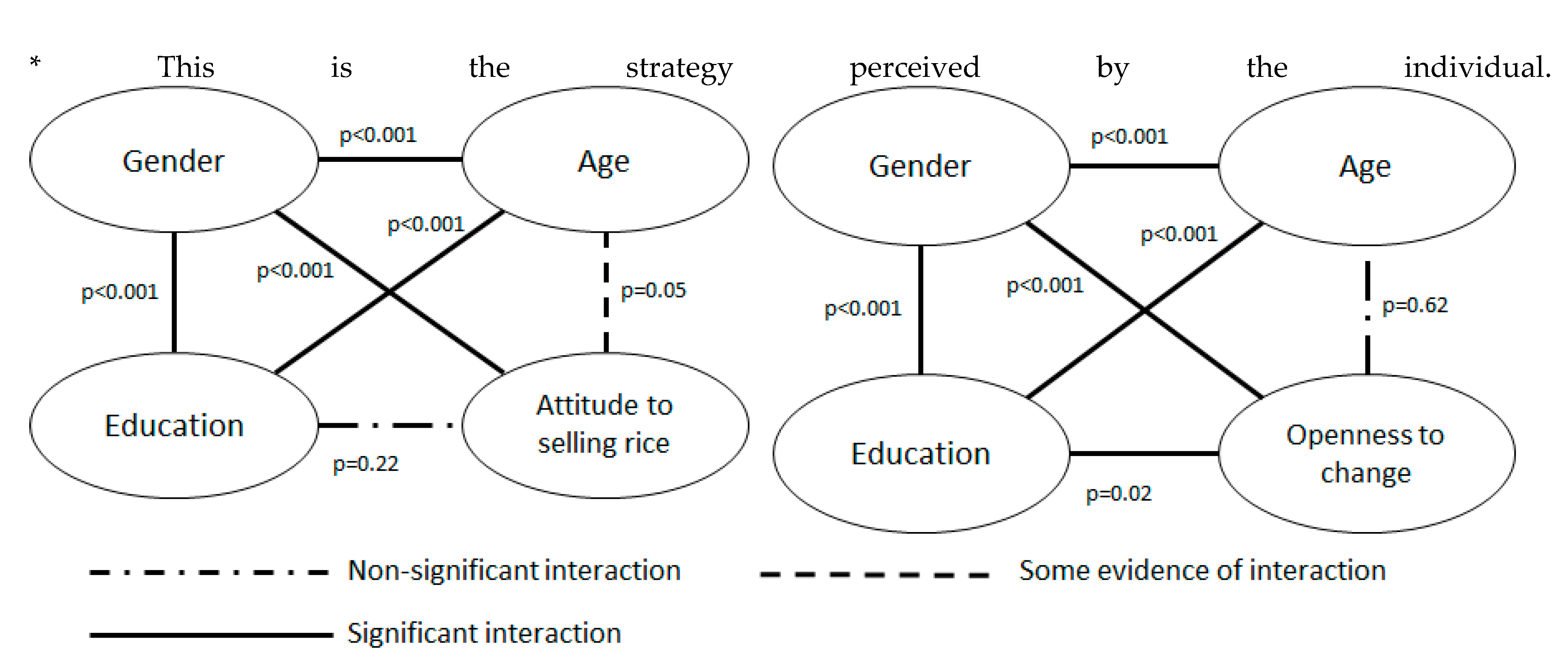

4.3. Gender-Related Differences in Strategy and Attitudes towards Rice Selling

- (1)

- Maximize farm income: As head of the household, I need to feed my family and make some extra money. I plan to have surplus rice for sale every year and I sell animals when I need extra money. Sometimes I get an off-farm job to make a bit more money.

- (2)

- Maximize off-farm income: As head of the household, it is my job to maximize labour time for off-farm jobs because this maximizes our income. It is not worth our effort to increase rice production much more than what we need to feed my family. Rice, animals, and cash crops are important, but off-farm jobs are the best way to maximize income.

- (3)

- Not head of household.

- (1)

- Modern farmer: I farm like most other farmers around here. There must be a very good reason for me to do something very different from what most other farmers do.

- (2)

- Pragmatist: I am interested in what other farmers do but if it suits me, I will do things differently to other farmers.

- (3)

- Traditionalist: I farm in the way that my parents and grandparents did. I do not want to change because farming in this way is part of who I am.

- (1)

- “Feed family: I am a farmer. I grow rice mainly to feed my family and sell any surplus.

- (2)

- Sell surplus: I am a farmer. I grow rice to feed my family and sell the surplus. I am always looking for opportunities to improve my income.

- (3)

- Entrepreneur: I am a farmer and entrepreneur. I grow rice to feed my family and for income. I am interested in anything that might help me make more money from growing rice.”

4.4. Gender-Related Differences in Household Income

- (1)

- Access to the market price for rice. “I can easily get the local market price for rice”. Stronger agreement with this statement was correlated with a higher household income. This factor was significantly associated with gender, with women being more likely to disagree with this statement.

- (2)

- Access to multiple buyers. “If I want to sell rice, I have several buyers available”. An agreement with this statement was generally associated with a higher household income and vice versa. The average access to multiple buyers was not statistically different for men and women; however, a statistically significant larger proportion of women reported strong disagreement with the statement that they “have access to multiple buyers”, indicating a small but important group that was particularly vulnerable.

- (3)

- Access to a fair price for seeds and other inputs. There was a statistically significant difference between women and men in response to question “I know I pay a fair price for seed, fertilizer and pesticide”, with women more likely to agree with this statement.

- (4)

- Priority for selling livestock. “How much do you prioritize selling livestock?” A higher stated priority of selling livestock was generally associated with a higher household income and vice versa. Women reported on average a lower priority for selling livestock.

- (5)

- Future-orientation. “When I think about improving my farm the most that I look ahead is x”. Participants responded to timeframes from “this season” to “more than three years”. Individual future orientation was strongly associated with household income. The level of future orientation revealed an interesting set of nuances. Most men and women considered productivity benefits season by season, and rarely did participants consider benefits a year or two into the future. However, on average women reported a higher level of longer-term future-orientation (>3 years); and the individuals with this long-term view reported the lowest average household incomes. As many as 15% of women looked more than 3 years into the future, compared to only 6% of the men. On the other hand, men reported a higher proportion of future-orientation in the middle range of one or two years—and the individuals with such a future-orientation reported the highest average household income.

5. Discussion

5.1. Gender-Related Differences in Education Level

5.2. Gender-Related Differences in the Embrace of New Practices

5.3. Gender-Related Differences in Livelihoods Strategy and Attitudes towards Farming

5.4. Gender-Related Differences in Economic Outcomes and Access to Market

5.5. Implications of Our Results for Research and Policy

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eliste, P.; Santos, N.; Pravongviengkham, P.P. Lao People’s Democratic Republic Rice Policy Study; IRRI, World Bank: Metro Manila, Philippines, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Lao Census of Agriculture 2010/11: Analysis of Selected Themes; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry: Vientiane, Laos, 2014.

- Alexander, K.; Millar, J.; Lipscombe, N. Sustainable Development in the Uplands of Lao PDR. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.; Case, P.; Jones, M.; Connell, J. Commercialising smallholder agricultural production in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Dev. Pract. 2017, 27, 965–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foppes, J. Fish, Frogs, and Forest Vegetables: Role of Wild Products in Human Nutrition and FOOD Security in Lao PDR; IUCN: Vientiane, Laos, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, I.G.; Barney, K. The Political Ecology of Cross-Sectoral Cumulative Impacts: Modern Landscapes, Large Hydropower Dams and Industrial Tree Pantations in Laos and Cambodia. J. Peasant Stud. 2017, 44, 769–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koninck, R. The Challenges of the Agrarian Transition in Southeast Asia. LabourCap. Soc. 2004, 37, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Castella, J.C. Keynote 1: Agrarian transition and farming system dynamics in the uplands of South-East Asia. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Conservation Agriculture in Southeast Asia, Hanoi, Vietnam, 10–14 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, S. Structural Change, Growth and Poverty Reduction in Asia: Pathways to Inclusive Development. Dev. Policy Rev. 2006, 6, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J. Prospects and Challenges for Growth and Poverty Reduction in Asia. Dev. Policy Rev. 2006, 24, s29–s49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, G. Agrarian Change and the Governance of Poverty in Southeast Asia. In Proceedings of the 9th Euroseas Conference, Oxford, UK, 16–18 August 2017; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Castella, J.C.; Lestrelin, G.; Buchheit, P. Agrarian transition in the northern uplands of Lao PDR: A meta-analysis of changes in landscapes and livelihoods. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Conservation Agriculture in Southeast Asia, Hanoi, Vietnam, 10–15 December 2012; pp. 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Agriculture Development Strategy to the Year 2025 and Vision to 2030; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry: Vientiane, Laos, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cramb, R.A.; Gray, G.D.; Gummert, M.; Haefele, S.M.; Lefroy, R.D.B.; Newby, J.C.; Stür, W.; Warr, P. Trajectories of Rice-Based Farming Systems in Mainland Southeast Asia; ACIAR Monograph No. 177; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Cramb, R. White Gold: The Commercialisation of Rice Farming in the Lower Mekong Basin; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Stür, W.; Gray, G.D. Review of Rice-Based Farming Systems in Mainland Southeast Asia Working Paper 3. Livestock in Smallholder Farming Systems of Mainland Southeast Asia; University of Queensland Australia and International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vote, C.; Newby, J.; Phouyyavong, K.; Inthavong, T.; Eberbach, P. Trends and perceptions of rural household groundwater use and the implications for smallholder agriculture in rain-fed Southern Laos. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2015, 31, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WB (World Bank); IRRI (International Rice Research Institute). Lao People’s Democratic Republic Rice Policy Study; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry of the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Vientiane, Laos, 2012.

- Clarke, E.; Jackson, T.M.; Keoka, K.; Phimphachanvongsod, V.; Sengxua, P.; Simali, P.; Wade, L.J. Insights into adoption of farming practices through multiple lenses: An innovation systems approach. Dev. Pract. 2018, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M.; Alexander, K.; Thephavanh, M.; Thammavong, P.; Sodahak, V.; Khounsy, B.; Vorlasan, S.; Larson, S.; Connell, J.; Case, P. A Bayesian Network model to explore practice change by smallholder rice farmers in Lao PDR. Agric. Syst. 2018, 164, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philp, J.N.M.; Vance, W.; Bell, R.W.; Chhay, T.; Boyd, D.; Phimphachanhvongsod, V.; Denton, M.D. Forage options to sustainably intensify smallholder farming systems on tropical sandy soils. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieri, S. New ruralities-Old gender dynamics? A reflection on high-value crop agriculture in teh light of the femenisation debates. Geogr. Helv. 2014, 69, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Razavi, S. The Genedered Impacts of Liberalization; UNRISD Research in Gender and Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Arnst, R. Donors, Development and the Decline of Lao Civil Society. New Mandala 2014. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Country Gender Assessment of Agriculture and the Rural Sector in Lao PDR; FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Vientiane, Laos, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.S.; Greenhalgh, G.; Moglia, M.; Thephavanh, M.; Sinavong, P.; Larson, S.; Jovanovic, T.; Case, P. What is technology adoption? Exploring the agricultural research value chain for smallholder farmers in Lao PDR. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, G.; Moglia, M.; Alexander, K.; Jovanovic, T.; Sacklokham, S.; Khounsy, B.; Thaphavanh, M.; Inthavong, T.; Vorlasane, S.; Khampaseut, M. Smallholder Farmer Decision-Making and Technology Adoption in Southern Lao PDR: Opportunities and Constraints. Activity 1.1: Farmer Perception Survey; ACIAR: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Akter, S.; Rutsaert, P.; Luis, J.; Htwe, N.M.; San, S.S.; Raharjo, B.; Pustika, A. Women’s empowerment and gender equity in agriculture: A different perspective from Southeast Asia. Food Policy 2017, 69, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East Asia Forum. Gender and sexuality in Asia today. In Economics, Politics and Public Policy in East Asia and the Pacific; East Asia Forum: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.K.; Khanal, A.R.; Mohanty, S. Gender differentials in farming efficiency and profits: The case of rice production in the Philippines. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phouxay, K.; Tollefsen, A. Rural–Urban Migration, Economic Transition, and Status of Female Industrial Workers in Lao PDR. Popul. Space Place 2011, 17, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phimphanthavong, H. Economic Reform and Regional Development of Laos. Mod. Econ. 2012, 3, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manivong, V.; Cramb, R.; Newby, J. Rice and Remittances: Crop Intensification Versus Labour Migration in Southern Laos. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 42, 367–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manivong, V.; Cramb, R.; Newby, J. Rice and Remittances. The Impact of Labour Migration on Rice Intensification in Southern Laos. In Proceedings of the 56th AARES Annual Conference, Fremantle, Australia, 7–10 February 2012; Australian Agricultural & Resource Economics: Fremantle, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, J. Moving lives: Migration and livelihoods in the Lao PDR. Popul. Space Place 2007, 13, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, J. Unplanned Development: Tracking Change in South-East Asia; Zed Books: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mekong Commons. Migrant workers from Laos: Benefits tempered with high risks. Available online: http://www.mekongcommons.org/migrant-workers-laos-benefits-tempered-risks (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Alexander, K.S. Agricultural Change in Lao PDR: Pragmatism in the Face of Adversity; Charles Sturt University: Albury-Wodonga, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ducourtieux, O.; Laffort, J.-R.; Sacklokham, S. Land Policy and Farming Practices in Laos. Dev. Chang. 2005, 36, 499–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Women’s Economic Empowerment and Inclusive Growth: Labour Markets and Enterprise Development; Department for International Development (DFID): London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nazneen, S. Rural Livelihoods and Gender; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Country Analysis Report: Lao PDR Analysis to Inform the Lao People’s Democratic Republic–United Nations Partnership Framework (2017–2021); United Nations: Vientiane, Laos, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sengphachanh, M. Women’s Participation in Value Chain of Coffee Production in Southern of Lao PDR; National University of Laos: Vientiane, Laos, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sengphachanh, S. Coffee Plantation for Export affects to the Change of Gender Status at Lak 35 Village, Pakxong District, Champasack Province; National University of Laos: Vientiane, Laos, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, E.K. Role of Women in Agriculture: A Micro Level Study. J. Glob. Econ. 2006, 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Petesch, P.; Badstue, L. Gender Norms and Poverty Dynamics in 32 Villages of South Asia. Int. J. Commun. Well Being 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SIDA. National Gender Profile of Agricultural Households, Lao PDR 2010. Report Based on the Lao Expenditure and Consumptrion Surveys, National Agricultural Census and the National Population Census; SIDA: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.; Larson, S. Smallholder Farmer Decision-Making and Technology Adoption in Southern Lao PDR: Opportunities and Constraints. Activity 1.5: Stakeholders PERCEPTIONS. Report for ACIAR ASEM/2014/052 project ‘Smallholder Farmer Decision-Making and Technology Adoption in Southern Laos: Opportunities and Constraints; ACIAR: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.; Larson, S.; Moglia, M.; Greenhalgh; Case, P.; Perez, P.; Jovanovic, T.; Giger-Dray, A. Smallholder Farmer Decision-Making and Technology Adoption in Southern Lao PDR: A Synthesis of Findings; ACIAR: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, S.; Alexander, K. Smallholder Farmer Decision-Making and Technology Adoption in Southern Lao PDR: Opportunities and Constraints. Activity 1.4 Summary of the Secondary Livelihoods and Economic Data. Report for ACIAR ASEM/2014/052 project ‘Smallholder FARMER decision-Making and Technology Adoption in Southern Laos: OPPORTUNITIES and constraints’; ACIAR: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, K.; Parry, L.; Thammavong, P.; Sacklokham, S.; Pasouvang, S.; Connell, J.; Jovanovic, T.; Moglia, M.; Larson, S.; Case, P. Rice farming systems in Southern Lao PDR: Interpreting farmers’ agricultural production decisions using Q methodology. Agric. Syst. 2018, 160, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dray, A.; Perez, P.; Larson, S.; Moglia, M.; Alexander, K. Using serious games to explore gender differences in smallholder decisions to adopt new farming practices: Example of white rice production in Lao PDR. Sustainability 2020. (Forthcoming). [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, G.; Alexander, K.S.; Larson, S.; Thammavong, P.; Sacklohkham, S.; Thephavanh, M.; Sinavong, P.; Moglia, M.; Perez, P.; Case, P. Transdisciplinary agricultural research in Lao PDR. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 72, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, O. The agrarian transition and the ‘feminization’ of agriculture. In Food Sovereignty: A Critical Dialogue, International Conference; Yale University: New Haven, CT, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, G.; Just, R.E.; Zilberman, D. Adoption of Agricultural Innovations in Developing Countries: A survey. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1985, 33, 255–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marra, M.; Pannell, D.J.; Ghadim, A.A. The economics of risk, uncertainty and learning in the adoption of new agricultural technologies: Where are we on the learning curve? Agric. Syst. 2003, 75, 215–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattler, C.; Nagel, U.J. Factors affecting farmers’ acceptance of conservation measures—A case study from north-eastern Germany. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, A.P.; Thompson, A.W.; Prokopy, L.S. The multi-dimensional nature of environmental attitudes among farmers in Indiana: Implications for conservation adoption. Agric Hum Values 2012, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotter, J.P. Leading Change; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rafferty, A.E.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Armenakis, A.A. Change Readiness: A Multilevel Review. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 110–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Struckman, C.K.; Yammarino, F.J. Organizational Change: A Categorization Scheme and Response Model with Readiness Factors. In Research in Organizational Change and Development; Woodman, R., Pasmore, W., Shani, A.B., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; Volume 14, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Dray, A.; Cornioley, T.; Larson, S.; Perez, P.; Thammavong, P.; Thephavanh, M.; Sinavong, P.; Alexander, K. Using serious games to understand gender differences in smallholder agricultural production decisions in Lao PDR. Sustainability 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mudege, N.N.; Mdege, N.; Abidin, P.E.; Bhatasara, S. The role of gender norms in access to agricultural training in Chikwawa and Phalombe, Malawi. Gend. Place Cult. 2017, 24, 1689–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andriesse, E.; Phommalath, A. Provincial Poverty Dynamics in Lao PDR: A Case Study of Savannakhet. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2012, 3, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inthasone, P. Preliminary Assessment on Trafficking of Children and Women for Labour Exploitation in Lao PDR: ILO-IPEC, International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour in Collaboration with the Mekong Sub-regional Project to Combat Trafficking in Children and Women. SNV Lao, Vientiane, Lao PDR; SNV Lao: Vientiane, Laos, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Population Census. Results from the Population and Housing Census 2005; National Statistic Department: Vientiane, Laos, 2015.

- Luna, J.K. ‘Pesticides are our children now’: Cultural change and the technological treadmill in the Burkina Faso cotton sector. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, J.; Salamanca, A.; Phongsiri, M.; Sripun, M. More farmers, less farming? Understanding the Truncated Agrarian Transition in Thailand. World Dev. 2018, 107, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.A.; Gillen, J.; Rigg, J. Economic transition without agrarian transformation: The pivotal place of smallholder rice farming in Vietnam’s modernisation. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoppe-Sullivan, S.J.; Altenburger, L.E.; Lee, M.A.; Bower, D.J.; Dush, C.M.K. Who are the Gatekeepers? Predictors of Maternal Gatekeeping. Parent Sci. Pr. 2015, 15, 166–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- High, H. Fields of Desire. Poverty and Policy in Laos; NUS Press: Singapore, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, L.L. Women and the Global Economy. Gender Promotion Programme, International Labour Office. In Division for the Advancement of Women, Department for Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) United Nations; ILO: Beirut, Lebanon, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Summary Statistic | Women | Men | p-Value of Chi-Square Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of respondents who have adopted at least one technology (% NumberOfTechs > 0) | 43% | 42% | 0.06. |

| Average number of technologies adopted (NumberOfTechs) | 0.79 | 0.97 | |

| Percentage involved in testing new practices (ProjectInvolvement) | 48% | 43% | 0.17 |

| Average number of technologies still being used (StillUsing) | 0.93 | 0.88 | <0.001 *** |

| Average number of useful technologies per adopter (BeingUseful) | 1.9 | 1.5 | <0.001 *** |

| Percentage of adopters who are using at least one useful technology (BeingUseful) | 83% | 89% |

| Question | Response | Female Respondents (%) | Male Respondents (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards selling rice | Feed family | 9% | 12% |

| Entrepreneur | 65% | 52% | |

| Sell surplus | 27% | 36% | |

| Openness to change | Modern farmer | 23% | 29% |

| Pragmatist | 49% | 42% | |

| Traditionalist | 28% | 29% | |

| Household farming strategy * | Feed family | 10% | 19% |

| Maximize farm income | 27% | 44% | |

| Maximize off-farm income | 62% | 36% |

| Question | Men—Average Score | Women—Average Score | p-Value (for Chi-Square Test Against Gender) a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to market price for rice | 0.33 | 0.28 | <0.01 *** |

| Access to multiple buyers | 0.86 | 0.86 | <0.01 *** |

| Access to fair price when selling rice | 0.11 | 0.24 | <0.01 *** |

| Access to a fair price for seed and other inputs | 0.23 | 0.35 | <0.01 *** |

| Priority of selling livestock | 0.84 | 0.77 | 0.02 * |

| Future-orientation | 0.63 | 0.84 | <0.01 *** |

| Factor | Estimate | Pr (>|t|) | % of Deviance Explained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Future orientation | −0.18 | 2.27 × 10−5 *** | 2.9% |

| Access to multiple buyers | 0.067 | 0.014 * | 2.4% |

| Access to market price | 0.054 | 0.033 * | 0.7% |

| Household farmer strategy: Max. farm income | 0.080 | 0.027 * | 1.7% |

| Household farmer strategy: Max. off-farm income | 0.058 | 0.10 | |

| Household Farmer strategy: Feed family | 0 | N/A | |

| Openness to change: Pragmatist | 0.017 | 0.53. | 0.7% |

| Openness to change: Modern farmer | 0 | N/A | |

| Openness to change: Traditionalist | −0.043 | 0.14 | |

| Attitude towards selling rice: Feed the family | 0 | N/A | 0.6% |

| Attitude towards selling rice: Sell surplus | −0.066 | 0.069. | |

| Attitude towards selling rice: Entrepreneur | −0.11 | 0.0030 ** | |

| Gender: Male | 0.053 | 0.032 * | 0.5% |

| Gender: Female | 0 | N/A | |

| PriorityFarmIncome | −0.092 | 0.029 * | 0.4% |

| PriorityOffFarmIncome | 0.060 | 0.078. | 0.4% |

| PriorityLivestock | 0.0018 | 0.96 | 0% |

| Education | 0.0144 | 0.61 | 0% |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moglia, M.; Alexander, K.S.; Larson, S.; -Dray, A.; Greenhalgh, G.; Thammavong, P.; Thephavanh, M.; Case, P. Gendered Roles in Agrarian Transition: A Study of Lowland Rice Farming in Lao PDR. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5403. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135403

Moglia M, Alexander KS, Larson S, -Dray A, Greenhalgh G, Thammavong P, Thephavanh M, Case P. Gendered Roles in Agrarian Transition: A Study of Lowland Rice Farming in Lao PDR. Sustainability. 2020; 12(13):5403. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135403

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoglia, Magnus, Kim S. Alexander, Silva Larson, Anne (Giger)-Dray, Garry Greenhalgh, Phommath Thammavong, Manithaythip Thephavanh, and Peter Case. 2020. "Gendered Roles in Agrarian Transition: A Study of Lowland Rice Farming in Lao PDR" Sustainability 12, no. 13: 5403. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135403

APA StyleMoglia, M., Alexander, K. S., Larson, S., -Dray, A., Greenhalgh, G., Thammavong, P., Thephavanh, M., & Case, P. (2020). Gendered Roles in Agrarian Transition: A Study of Lowland Rice Farming in Lao PDR. Sustainability, 12(13), 5403. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135403