1. Introduction

Rapid industrialization, along with the increased globalization, has led to far-reaching, detrimental effects on the natural environment, such as environmental pollution and contamination, and sharp depletion of natural resources. Corporations, as a major source of environmental degradation [

1], are now under immense pressure to undergo necessary reforms that ensure environmental preservation while achieving their financial goals [

2]. Sustainable development has, thus, become indispensable for every organization to survive in the modern era [

3]. Scholars have forwarded various concepts to promote sustainable development, among which environmental (green) accounting is one such concept that aims to incorporate the cost of the ecological impact of companies’ operations into conventional accounting systems. Schaltegger and Burritt [

4] (p. 30) define environmental accounting as a “branch of accounting that deals with activities, methods, and systems; recording, analysis, and reporting; and environmentally induced financial impacts and ecological impacts of a defined economic system.” Environmental accounting (EA), in this way, incorporates environmental costs into the financial results of a company’s operations. This would help the companies to understand the magnitude of the impact of companies’ operations on the natural environment. Moreover, with the EA reports, business owners and managers will develop a better sense of their environmental expenditures, which is the first step towards strategic management and innovative planning for controlling these expenditures. Furthermore, it provides a holistic picture of the overall financial position and increases the awareness of management and other shareholders about the true cost of natural resources consumed in making revenues [

5]. The EA practice, therefore, is seen as an essential component of the environmental decision-making process within the corporate sector [

6]. The present study examines how well corporate managers in the developing world have perceived these benefits and how such perceptions shape their behavioral intentions towards EA practices.

The importance of EA is also reflected in the recent proliferation of rules and regulations that mandate companies to establish EA practices and to disclose environmental information for the reference of their stakeholders [

3]. Countries like Denmark, Netherland, the US, and Japan have promulgated specific laws requiring companies to disclose environmental information. Multinational corporations are now evaluating their suppliers in terms of environmental performance and its disclosure before entering into business agreements [

3,

7]. However, despite all these efforts, major corporate scandals, such as the Volkswagen emissions scandal, Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Kobe steel scandal, and iPhone battery scandal, have raised serious concerns about the adoption and compliance with these regulations and the best practices within the corporate sector. In addition, these incidents shake stakeholders’ confidence in corporate conduct, which may have a widespread impact on the entire corporate sector. From the accounting standpoint, these scandals stress the importance of EA implementation. Some practitioners argued that the potential cost of environmental contingencies such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill could have been estimated if a proper EA system was in place [

5]. They further argue that massive financial losses (i.e., fines, penalties, loss of market value) associated with these environmental catastrophes could have been prevented with proper EA practices. However, implementation of such best practices (i.e., EA practices) within corporate sectors depends upon several factors, ranging from countries’ political, economic, and legal environments to corporate managers’ cognitive and psychological factors [

8,

9,

10]. Therefore, a thorough investigation of these factors is inevitably needed, since the identification of key factors is the first step towards developing and implementing the necessary policies.

Although scholars have made substantial efforts to theorize the concept of EA [

11,

12], most empirical studies are largely narrowed around the disclosure issues of the corporate sector [

9]. These studies predominantly focus on environmental disclosure and firm performance [

10,

13], determinates of environmental disclosure, level of environmental disclosure [

14,

15], development of disclosure indices [

16,

17], etc. However, the managerial side of EA implementation is often overlooked [

18,

19,

20]. Few studies have investigated the managerial perspectives of other accounting and reporting practices related to sustainable development, such as sustainable reporting and corporate social responsibility reporting [

8,

18,

21]. This specific issue of managers’ behavioral intention to engage in EA implementation, to the best of our knowledge, has not yet been studied in the accounting literature. Given this paucity of studies, there is a strong need to look at managers’ viewpoints, thus broadening the horizons and empirical evidence related to the subject matter. It is indeed a problem for managers to adopt a practice while ensuring the profitability of the business. Looking at this issue from the managers’ viewpoint can give an idea about pertinent hindrances to the adoption of EA practices by businesses. Thus, for recommending a suitable implementation strategy, it is important to analyze the current perceptions and attitudes of managers towards the EA practice for corporate sustainability. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to investigate the behavioral intentions of managers to engage in EA practices using a theory triangulation approach. To this end, theories such as neo-institutional theory [

22], stakeholder theory [

23], and legitimacy theory [

24] explain why EA practices are important and how EA practices are diffused among companies [

25], while the theory of planned behavior (TPB) provides the theoretical basis for conceptualizing managerial intentions towards EA practices. The TPB, with its roots in social psychology, tries to explain why people would favor one action over the other [

26,

27]. This will help to uncover factors that support or converse with the idea of EA in a business, which, in turn, provides an understanding of how EA can be promoted in the corporate industry and what regulatory measures need to be taken in order to make it an obligation for all applicable businesses.

While this study addresses the existing research gaps concerning the managerial aspect of EA implementation, it tries to apply novel theoretical approaches in the context of EA as a response to the call of Gray et al. [

28] and Parker [

19,

20] for additional research in social and environmental accounting using psychology theories. This study is also motivated by the prevalent environmental issue in Sri Lanka, whose magnitude has grown considerably over the years [

29]. Previous studies have found that the majority of business enterprises in Sri Lanka have neglected environmental restoration [

30]. However, recently, public awareness and concern about environmentally harmful activities are growing in Sri Lanka and several other developing countries, making it an important topic of discussion within the corporate sector [

31]. In Sri Lanka, public opinion is now forcing a radical change in corporate practices, and environmental restoration is now also appearing in electoral campaigns. These changing dynamics motivate the need for research to understand the internal and external drivers for EA practices in the developing countries, where businesses are just stepping into their role in protecting the environment.

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, this study can be considered as one of the first studies to extend the current empirical evidence related to EA practices from a socio-psychological context. Hence, in contrast with previous studies that are narrowed around EA goals, measures, and disclosure issues [

8,

18,

32,

33,

34,

35], this study fills the gap in the literature by providing pieces of evidence on the antecedents of managers’ behavioral intentions to engage in EA, making a significant theoretical contribution. The intensity of sustainable practices by a firm rests heavily on the green climate of an organization [

36], and managers’ attitudes and intentions towards such practices are essential components of it [

8,

18]. Thus, by providing the managers’ perspectives related to EA implementation, this research has shed light on the underlying issues that revolve around the EA practice and its implementation. Second, this study demonstrates the usefulness of behavioral theories in explaining the importance of managers’ attitudes, perceptions, and intentions in the domain of EA practices. Linking the dimensions of TPB with other theories pertaining to EA practices, such as neo-institutional theory, stakeholder theory, and legitimacy theory, this study shows that managerial attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control are significant predecessors to managerial intention to engage in EA practices. In addition, the integration of novel constructs, such as perceived cost and complexity, regulatory pressure, and organizational environmental orientation to TPB, in explaining managerial intentions towards EA practices is also a significant contribution to the literature. Third, the use of a novel approach, a partial least square structural equation modeling technique (PLS-SEM), in the context of EA for the assessment of socio-psychological parameters involved in the implementation of EA, can be considered as the methodological contribution of this study. The PLS-SEM approach is widely used in marketing and strategic management disciplines, but is rarely used in the EA context. This study shows the plausibility of the application of PLS-SEM in the context of EA. Furthermore, the majority of the previous research focused on developed countries, where there is a strong sense of environmental restoration and strict regulations towards it. On the contrary, many of the underdeveloped countries do not have the same favorable atmosphere to push strong environmental ethics, and, therefore, providing managerial perspective and intention from a developing country will contribute to expanding the present empirical evidence pertinent to the EA.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 discusses the research context and the link between EA and corporate sustainability, and provides a theoretical framework and rationale for hypothesis development.

Section 3 outlines the research methods of the study. In

Section 4, the results of the PLS-SEM analysis are presented.

Section 5 provides the results and discussion, followed by the conclusions, implications, and limitations in

Section 6.

4. Reliability and Validity Test Results

The results of the relevant tests for the reliability and validity of the measurement model are reported in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for each indicator along with the outer loading. The mean values for items pertaining to the latent construct of “Behavioral Intent to Engage in EA (INTENT)” are relatively low, indicating less managerial intention to engage in EA practices. However, the mean values of the items in the constructs of “Attitudes towards EA Practices (ATTI)” and “Subjective Norms (NORMA)” are above the theoretical average (i.e., 3.5), suggesting overall positive attitudes towards EA practices and increasing normative pressure towards EA implementation. On the other hand, the highest mean values can be observed in the items related to the latent construct of “Perceived Cost and Complexity (COXCS)”, which suggests that corporate managers in Sri Lanka consider EA practices to be more costly and burdensome. With regard to the normality of the data, excess kurtosis and skewness suggest that the data are non-normally distributed. However, this is not problematic, as the PLS-SEM can handle non-normal data effectively [

87].

Consistently with the measurement theory, we first examine the outer loadings of indicators. The majority of the indicators (i.e., 28 indicators out of 35) have satisfactory outer loadings and exceed the recommended minimum value of 0.708 [

81,

85]. The outer loadings of the rest of the indicators are also not problematic, as they are between 0.4 and 0.7 [

86]. Moreover, we observe that the removal of these indicators did not increase the composite reliability (CR) of the respective constructs [

86]. As for the internal consistency reliability, we used two measures: Cronbach’s Alpha and CR, the results of which are reported in

Table 1. Both the Cronbach’s Alpha and CR values are within the recommended range (Cronbach’s Alpha > 0.7 and 0.7 < CR > 0.95); hence, internal consistency reliability is established [

84,

85,

86,

88]. The convergent validity of each of the constructs was determined to refer to the average variance extracted (AVE). All the AVE values related to each of the constructs are above the minimum acceptable value (i.e., 0.5 or above), as shown in

Table 2, and, therefore, exhibit an appropriate level of convergent validity [

85,

86].

The statistical properties related to the discriminant validity of the constructs in the structural model are also adequate. Three metrics were used to determine the discriminant validity (DV): Fornell–Larker Criterion, cross-loadings, and Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) [

85,

86]. The outer loading of each indicator on the respective construct is higher than all of its cross-loadings on the other constructs in the model [

89]. Similarly, the Fornell–Larker Criterion analysis reported in

Table 3 also shows that the square root of the AVE value of each construct is greater than its correlation with other constructs [

90]. Furthermore, the HTMT ratios of the correlations are well below the threshold value of 0.85, as shown in

Table 4 [

91]. Additionally, the VIF values reported in

Table 5 indicate that there is no multicollinearity issue in the model, and, hence, each construct is unique and distinct from other constructs in the model [

87].

5. Results and Discussion

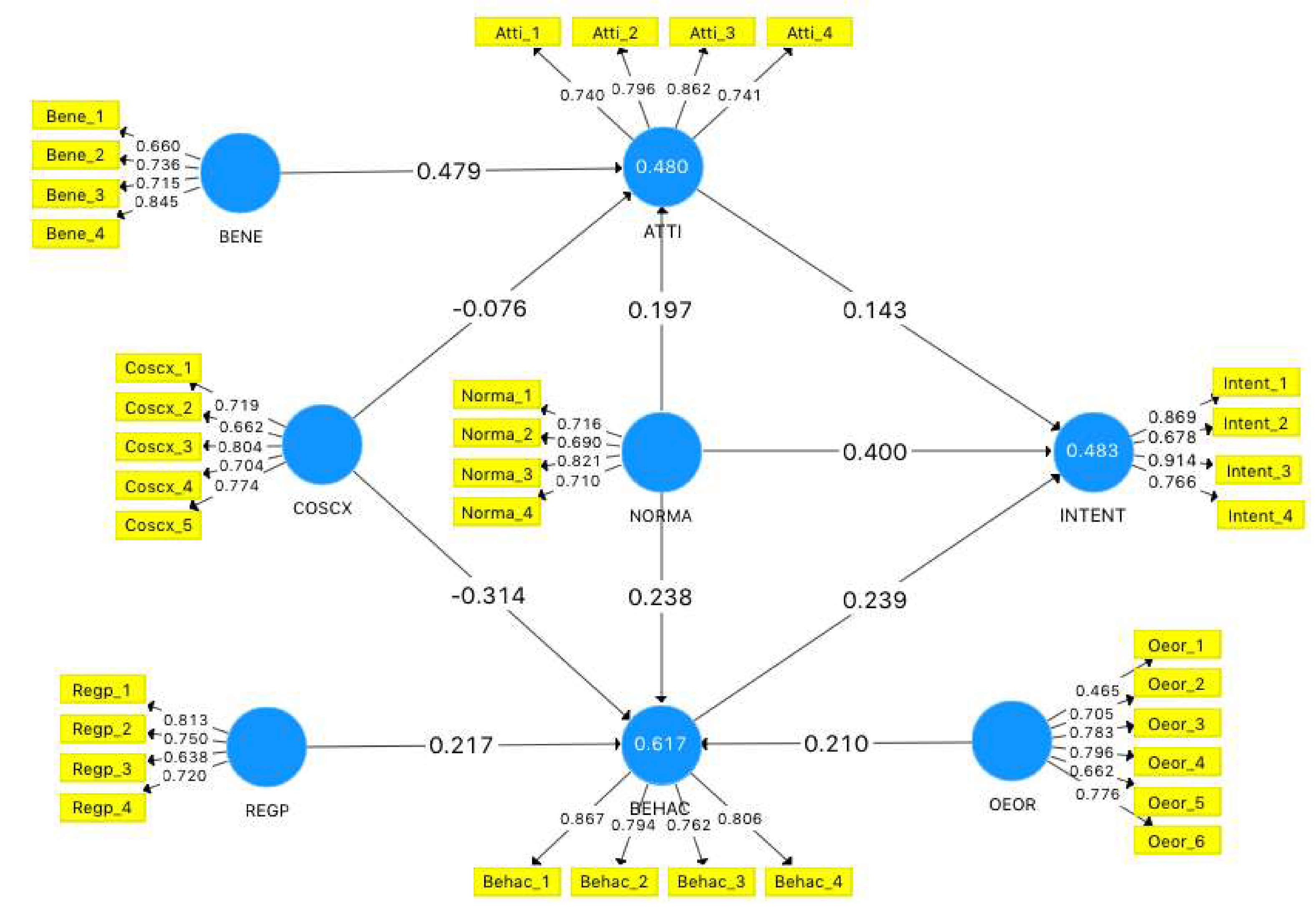

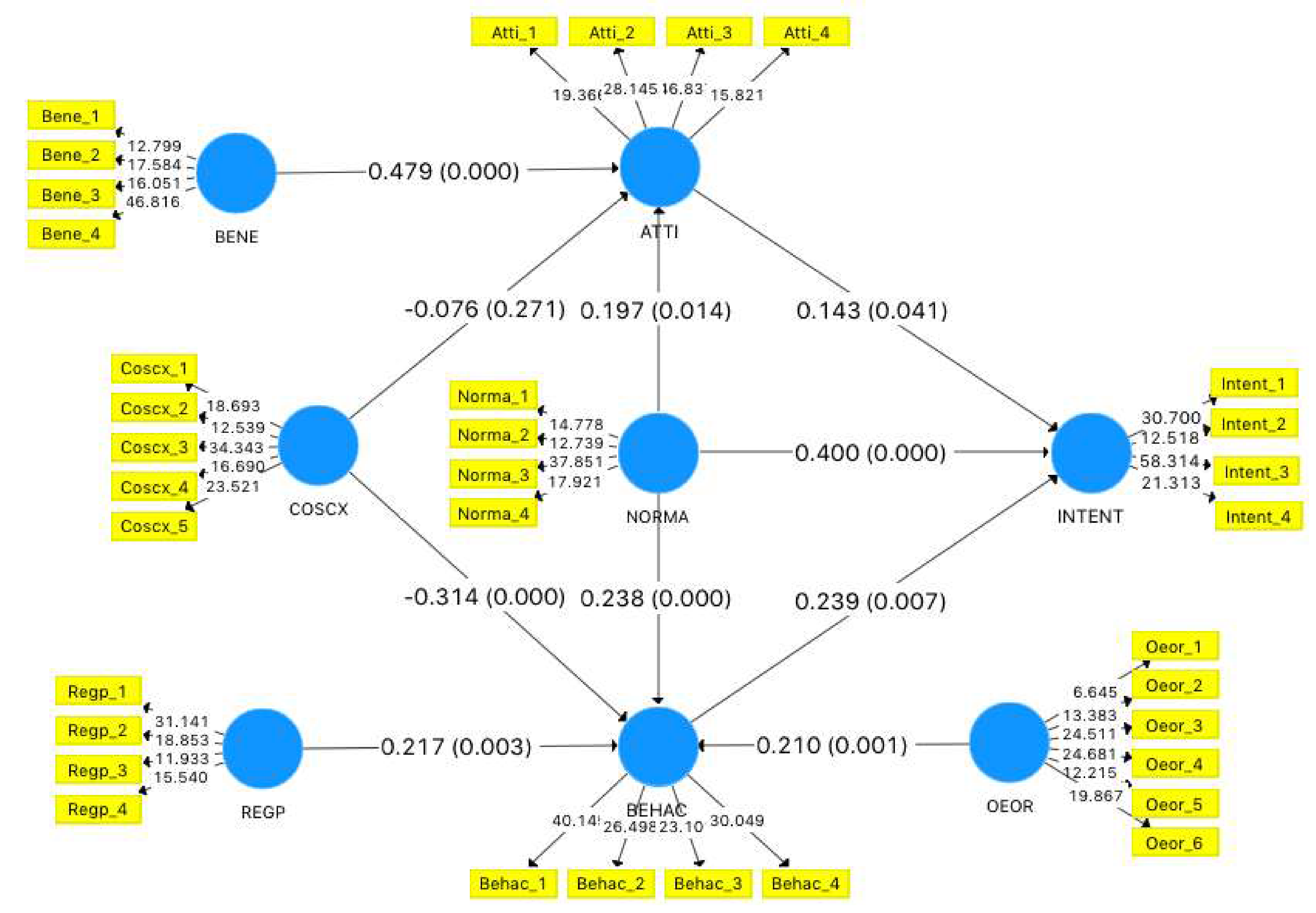

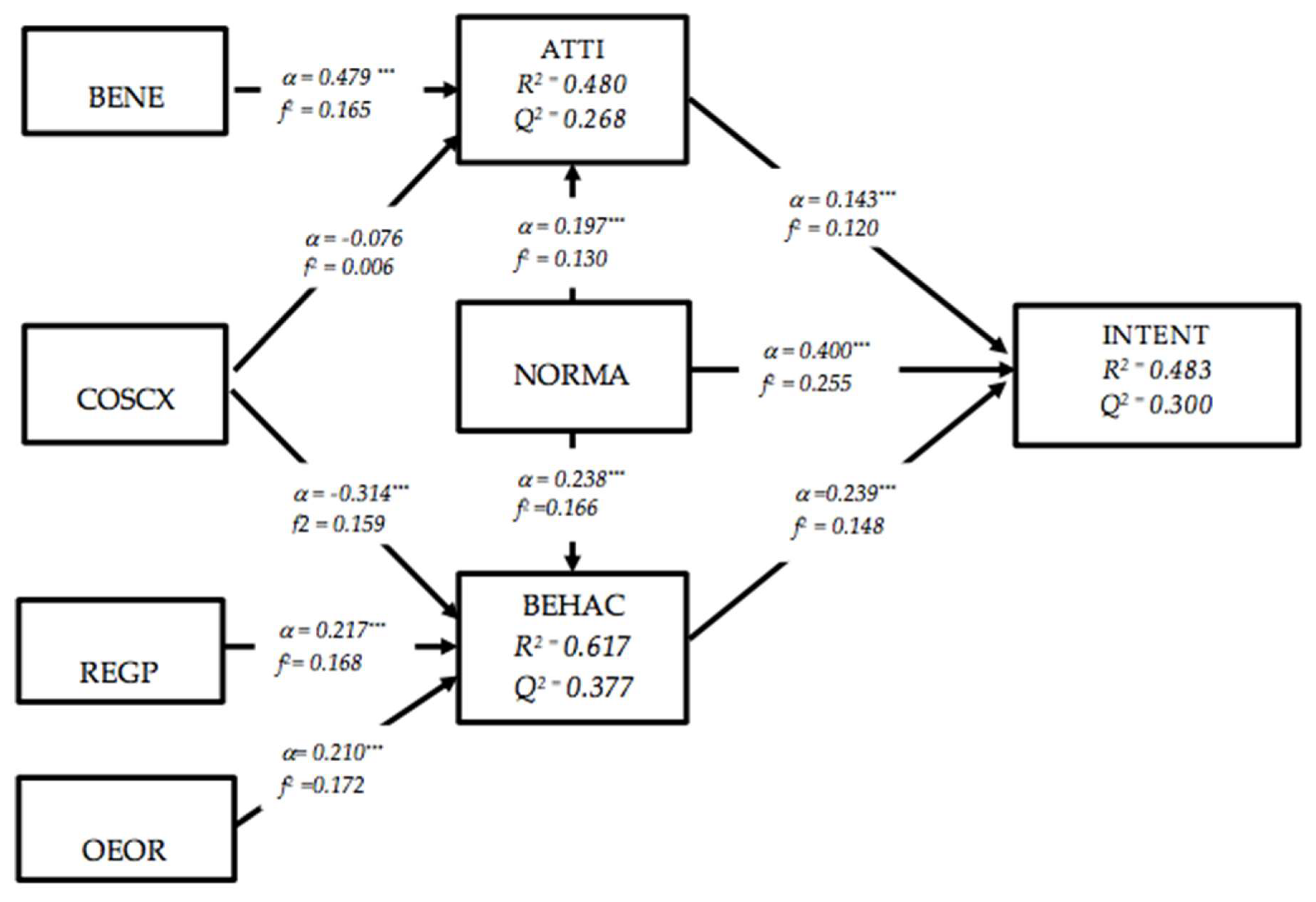

The results of the structural model evaluation are reported in

Table 6 and depicted in

Figure 2 (see also

Appendix B and

Appendix C). The direction and extent of the relationship between latent constructs are determined based on path coefficients [

85,

86,

92]. We used a 5000 subsample bootstrapping procedure to estimate the statistical significance of the path coefficients [

85,

86]. The hypothesized relationships between each variable were accepted or rejected accordingly.

5.1. Hypothesis Testing

Consistently with the TPB, we hypothesized a positive relationship between perceived benefits (BENE) and attitudes (ATTI) towards EA in H1. A positive and significant path coefficient (α = 0.479, p < 0.001) obtained from PLS-SEM analysis provides strong support for the H1. The H2a and H2b predicted a negative relationship between perceived cost and complexity (COSCX) and ATTI and between COSCX and perceived behavioral controls (BEHAC), respectively. Although both the path coefficients are negative (α = −0.076, α = −0.314), only the path coefficient between COSCX and BEHAC is statistically significant (α = −0.314, p < 0.001). Therefore, there is not enough evidence to accept H2a, yet we can accept H2b based on the present evidence. The H3 predicted a positive association between the perceived regulatory pressure (REGP) and BEHAC. Likewise, H4 expected a positive relationship between the organizations’ environmental orientation (OEOR) and BEHAC. The results of the PLS-SEM analysis support both the hypotheses H3 and H4 (α = 0.217, α = 0.210, p < 0.01). In addition, we postulated a positive association between subjective norms (NORMA) and other constructs in the model, such as ATTI, BEHAC, and intention to engage in EA practices (INTENT) in H5a, H5b, and H5c, respectively. Interestingly, these three hypotheses were all supported by the results, as the path coefficients are statistically significant (α = 0.400, α = 0.197, α = 0.238, p < 0.05). Another integral part of the TPB is the relationship between attitudes towards behavior and behavioral intention. In our study, this is reflected in the H6. As expected, ATTI is positively and significantly associated with INTENT (α = 0.143, p < 0.05). The results suggest that an increase in one standard deviation of ATTI increases the INTENT by 14.3%. The relationship between perceived behavioral control and behavioral intention in the EA context is predicted in the H7, and the same is supported by PLS-SEM results. That is, BEHAC positively and significantly influences the INTENT (α = 0.239, p < 0.01).

Concerning the path coefficients, the largest coefficients can be seen between BENE and ATTI, suggesting that managers who have perceived higher benefits in EA practices have acquired strong positive attitudes towards EA practices and vice versa. The effect size (

f2 = 0.165) also shows that the BENE is the best predictor of the ATTI in the present model. The coefficient of determination (

R2) of the endogenous variable ATTI is 48%, which means that both the exogenous variable BENE and COXCS account for almost half of the variance of managers’ attitudes towards EA practices in Sri Lanka. Concerning perceived behavioral control, all three exogenous variables (COSCX, REGP, OEOR) are either positively or negatively and significantly associated with BEHAC. These three variables explain 61.7% (

R2 = 0.617) of the variation of the BEHAC, as shown in

Figure 2. The INTENT, as the ultimate construct in the model, is significantly influenced by all its predecessors (ATTI, NORMA, BEHAC). While all three variables account for 48.3% of the variation of the INTENT, NORMA has the highest impact on the INTENT (α = 0.400, α = 0.197). Concerning the predictive accuracy and relevance of the path coefficients, Q

2 values of ATTI, BEHAC, and INTENT (0.268, 0.377, and 0.300) indicate an acceptable level [

86].

5.2. Multigroup Analysis

Our research involves listed companies as well as non-listed companies (private companies), and thus we performed a multi-group analysis (MGA) to determine the group-specific path coefficients, which are significantly different. This enables us to account for observed heterogeneity and thus avoid possible misinterpretations. This means that managerial intention towards corporate EA practices among listed and non-listed companies may vary to some degree due to various factors, such as the availability of resources, the extent of regulatory influence, geographic dispersion, and so on. This is evident from previous studies, such as that of Thoradeniya et al. [

8], which revealed that there are some differences in behavioral intention and actual behavior towards sustainable reporting practices between listed and non-listed companies in Sri Lanka. The use of MGA, therefore, allows us to analyze whether the structure of the relation between latent variables is stable across the sub-group of companies and, thereby, the conclusion of significant differences, if any, between listed and non-listed companies with regard to managers’ intention to engage in EA practices.

As with the main analysis, the MGA was performed using the PLS-SEM approach, and the analysis was carried out in Smart PLS statistical software. In carrying out our MGA, a three-step procedure, as suggested by Matthews [

93], was implemented. In the first step, we identified two pre-defined groups of companies as listed and non-listed companies. A total of 95 companies belonged to the group of listed companies, and 151 companies were included in the non-listed category. Upon defining the two groups, in the second step, we checked for measurement invariance to decide if the underline structures of the latent constructs of the two groups are comparable. To this end, we investigated configural invariance, compositional invariance, and equality of mean values and variance (i.e., measurement invariance of composite models) using the procedure suggested by Henseler et al. [

94]. However, we were unable to establish full measurement invariance, and only partial invariance was established, i.e., configural invariance and compositional invariance. According to Henseler et al. [

94], it is appropriate to compare path coefficients across multiple groups by establishing only partial invariances. The third step of the process was to assess the results of the statistical test for the MGA. The path coefficients of the two groups (i.e., listed and non-listed) were compared using the procedure called permutation, which is a separate option in the Smart PLS software. The permutation test is considered to be more appropriate than the other available methods (i.e., PLS-MGA, Parametric, Welch–Satterthwaite) [

93,

94].

Table 7 reports the results of the permutation test using 5000 iterations (it should be noted that

Table 6 shows only part of the results of the permutation test, and the rest of the results are not reported for the brevity of the paper).

The path coefficients for listed and non-listed companies are shown in columns one and two of

Table 6. Column three shows the differences between the path coefficients and their significance in the last column. Concerning listed companies, path coefficients somewhat deviated from the main analysis. In comparison to the main analysis, we find that several path coefficients (α = 0.116, α = 0.130) were no longer statistically significant (results are not reported) for listed companies. These results suggest that listed companies’ managers’ attitudes towards EA do not have a substantial effect on their intention to engage in EA practices; in addition, their perceived cost and complexity associated with EA have no impact on perceived behavioral controls. However, we find that certain relationships between latent variables are more pronounced in listed companies as compared to in the main analysis (i.e., NORMA to ATTI, NORMA to BEHAC).

In the case of non-listed companies, the findings indicate a noticeable variation concerning the significance of path coefficients as compared to the main analysis. For non-listed companies, the path coefficients from ATTI to INTENT, BEHAC to INTENT, NORMA to ATTI, NORMA to BEHAC, NORMA to INTENT, and REGP to BEHAC are not significant (results are not reported), while all these path coefficients are significant in the main analysis. Conversely, we find strong relationships between BENE and ATTI and between COSCX and BEHAC. This suggests that the perceived benefits of EA form the managers’ attitudes towards EA practices in non-listed companies. Moreover, the perceived cost and complexity involved in EA practices appear to be a major impediment to engaging in EA practices in non-listed companies. However, most of the predicted relationships cannot be observed in this separate analysis for the non-listed companies. Arguably, the reasons for this would be the lack of self-interest in EA, lack of EA knowledge, and the lack of regulatory and public pressure on EA practices in the context of non-listed companies.

Turning to the differences in path coefficients between listed and non-listed companies, the results indicate that only four predicted relationships are significantly different. Although the perceived cost and complexity involved in EA practices have a significant negative effect on the perceived behavioral controls in non-listed companies, the same is not significant in listed companies despite the negative sign. This can be explained by the fact that non-listed companies have fewer resources (i.e., financial and human) compared to listed companies, and, therefore, the resources required for EA practices might be considered to be higher. Next, we observe that the impact of normative pressure on managers’ intentions, attitudes, and behavioral control is significantly different between public and private companies. Our findings regarding normative pressure are consistent with previous studies, particularly that of Thoradeniya et al. [

8], which was conducted in Sri Lanka.

Additionally, our sample includes companies from different industries, such as manufacturing, hotel and leisure, banking, finance, and insurance, chemical and pharmaceutical, power and energy, construction, plantations, beverages, food, tobacco, etc. Previous studies suggest that firms operating in environmentally sensitive industries are heavily engaged in environmentally friendly practices, including EA, EMA, and CSR [

8,

95]. Thus, there might be a noticeable difference in managerial intention to engage in EA practice between companies in environmentally sensitive industries and other industries. Therefore, we identified two groups of companies based on their industry types, namely those in environmentally sensitive industries and others. In line with previous studies, companies that belong to the power and energy, chemical and pharmaceutical, and construction industries have been identified as being environmentally sensitive [

8]. There were 52 companies in the environmentally sensitive industries, and the rest of the companies are in the non-environmentally sensitive industries. Although we were able to identify two separate groups, we were not able to conduct an MGA using the PLS-SEM approach, since the measurement invariance could not be established.

However, the impact of industry type on the managerial intention to engage in EA practices was examined by incorporating a dummy variable (ENSEN) into the model. In this case, companies in environmentally sensitive industries were assigned one and the rest of the companies were assigned zero. Then, we re-estimated the model, and the results are depicted in the

Appendix D. The positive path coefficient indicates (

α = 0.489,

p < 0.001) that the managers’ intention to engage in EA practices is relatively high in the companies that belong to environmentally sensitive industries.

5.3. Discussion

Previous studies, which have examined the managers’ perspectives on CSR practices, have revealed attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control as the immediate predecessors of their intentions towards the practices [

8,

21,

75]. Drawing on the TPB and taking insights from the stakeholder theory, the legitimacy theory, and neo-institutional theory, this study empirically examined the antecedents of managers’ behavioral intention to engage in EA practices. The results suggest that the perceived benefits of EA practices have a significant effect on managers’ attitudes towards EA practices. On the other hand, perceived cost and complexity of EA practices have a substantial negative influence on perceived behavioral control, which could potentially minimize managers’ intention to engage in EA practices. The results also suggest that perceived regulatory pressure and organizational environmental orientation have a significant and positive relationship with perceived behavioral controls. In line with the main rationale of the TPB, this study demonstrates that the immediate predictors of managerial intention towards EA practices are attitudes towards the practices, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral controls.

There is a positive and significant relationship between the perceived benefits of EA and attitudes towards EA. However, in the MGA, this relationship only applies to listed companies. Indeed, managers in large companies are more knowledgeable and more concerned about environmental sustainability issues than managers in small companies [

96]. Managers’ perceptions of the benefits of EA may be subject to the knowledge, experience, and other concerns they have on environmental issues, and this may be the reason for the aforementioned difference between listed and non-listed companies. While the benefits–attitudes relationship from the main analysis is comparable to previous studies, the findings with respect to non-listed companies are inconsistent with Thoradeniya et al. [

8], where they found a significant and positive association between behavioral beliefs (mostly positive outcomes) and sustainability reporting attitudes in non-listed companies.

This study predicted that the cost and complexity of EA practices [

3] would negatively affect perceived behavioral control and attitudes towards EA practices. This suggests that managers who perceive EA practices as expensive and that such practices raise the administrative burden will have negative attitudes towards them. They may also perceive that higher costs and an increase in the complexity of administrative processes are obstacles to EA practices, and thus lower behavioral intentions through perceived behavioral control. However, our findings only endorse the expected relationship between COSCX and BEHAC. Although the relationship between COSCX and ATTI is negative, it is not statistically significant. While these results provide new evidence on how the cost and complexity involved in EA practices affect managers’ behavioral intentions, they are somewhat positioned with the findings of previous studies. For instance, Burzis Homi Ustad [

97] found that New Zealand hotel managers consider cost as the major barrier for the implementation of the environmental management systems. Our MGA has revealed an interesting phenomenon, where the negative relationship between COSCX and BEHAC is much stronger in non-listed companies than in listed companies. The same applies to the relationship between COSCX and ATTI despite statistical insignificance. This can be interpreted as the following: Small businesses (i.e., non-listed companies) find EA practices to be more costly and administratively burdensome.

We extended the TPB by replacing behavioral beliefs with three variables, namely perceived cost and complexity, perceived regulatory pressure, and organizational environmental orientation. Our findings indicate that these three variables are significantly associated with perceived behavioral control. Both the regulatory pressure and environmental orientation have a positive impact on perceived behavioral control. This indicates that companies that have already implemented environmentally friendly policies or procedures are more likely to engage in EA practices. In addition, the intention of managers to engage in EA practices appears to be stimulated by environmental rules and regulations, particularly in public companies. Our results are consistent with the findings of Rebeiro et al. [

70], where they found a positive association between the degree of development in environmental management practices and the level EA practices. These results also provide policymakers with the important insight that, by strengthening environmental regulations, they can encourage corporate managers to pursue more environmentally friendly practices within their firms.

There has been an increase in public concern over environmental degradation in Sri Lanka in recent years. Increased deforestation, garbage dumping problems in the capital city of Colombo, and rapid contamination of water were some of the main reasons for this. Ironically, our results indicate that the managers’ intention to engage in EA practices is mostly driven by normative pressure, which reflects growing public demand for environmental preservation in the country. Moreover, the impact of subjective norms on managerial intention to engage in EA practice is relatively higher in public companies. This could be because large companies are more visible and, therefore, subject to public criticism and scrutiny [

70,

98]. Our findings are consistent with previous studies [

8,

75]; Thoradeniya et al. [

8] found that subjective norms have a great influence on managers’ intention to engage in sustainability reporting in listed companies. Our findings also indicate that subjective norms significantly influence both attitudes towards EA practices and perceived behavioral control. These results not only accord with the TPB’s rationale, but are also consistent with previous studies.

In summary, we found that managers’ intention to engage in EA practices is affected by attitudes towards EA practices, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. However, these three constructs can explain only less than half of the variance of managers’ intentions, which suggests that more than half of the variance of managerial intention is accounted for by some other variables not included in this analysis. In addition, out of the three antecedents of managerial intention, subjective norms are shown to have a greater effect on managerial intention, which is aligned with environmental issues and related developments in the research context, Sri Lanka.

6. Conclusions, Implications, and Limitations

Research into EA practices is a growth area that has received increasing attention from both scholars and practitioners. This study attempted to answer the question: “What are the driving factors of managerial intention to engage in EA practices in Sri Lanka?” The TPB provides a theoretical basis for the conceptual model that addresses the research question. The model was tested using data collected through a standardized questionnaire from a sample of 247 top-level and middle-level managers of listed and non-listed companies in Sri Lanka. The results demonstrate the structural relationship between managerial intention to engage in EA practices and attitudes towards EA practices, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Our findings also indicate that the perceived benefits are the best predictors of attitudes towards EA practices. Moreover, the results indicate that the main barrier to engaging in EA practices is the cost and complexity involved in EA practices. Furthermore, organizational environmental orientation and perceived regulatory pressure are shown to have an incremental effect on the managers’ intention to engage in EA practices.

6.1. Theoretical Implications

Previous studies on EA and reporting have predominantly focused on the disclosure issue. However, the managerial side of EA implementation has often been overlooked. Shedding light on this issue, we contribute to the EA literature by examining managers’ intention to engage in EA practices and its key drivers. Our study also contributes to the literature by demonstrating the applicability of the TPB in the context of EA. Examining the influencing factors of behavioral intention to engage in EA practices in terms of multiple concepts and perspectives is vital, as it expands our understanding of the determinants of EA practices. Previous studies have predominantly used social theories, such as stakeholder theory, legitimacy theory, and neo-institutional theory, to explain the corporate adoption of sustainable management practices [

18,

40,

57]. Even though these theories provide a useful framework to identify the mechanism that affects the diffusion of sustainability management practices, it is questionable whether these theories are sufficient to explain the psychological factors that may affect the adoption of those practices [

8]. While there is a call for studies that explore new theoretical avenues [

8,

18], particularly psychological theories, in social and environmental accounting research, only a few studies have been directed towards this end so far [

8,

18]. As such, this study fills this void by illustrating the usefulness of the TPB in the EA domain, and empirically establishes the key influences of the managers’ intention to engage in EA practices. Although our descriptive analysis shows that the managers’ attitudes towards EA practices and intention to engage in EA practices are considerably low, there is a positive and significant relationship between attitudes and intention. Nonetheless, the most important predecessor of managerial intention to engage in EA practices is subjective norms, particularly in the case of listed companies. This is important because it is consistent with the findings of previous studies [

40,

58], which have used other social theories—for example, neo-institutional theory and stakeholder theory. Arguably, stakeholder pressure or institutional isomorphic forces first change the managers’ attitudes, perception, and behavioral intention over time, which ultimately results in structural changes in organizations.

Another key contribution of this study is the identification of novel constructs that explained more than half of the variance of perceived behavioral control. We showed that perceived regulatory pressure, organizational environmental orientation, and perceived cost and complexity have significantly influenced perceived behavioral control. We not only extend the TPB, but also provide a useful framework to identify behavioral factors that influence the adoption of sustainability practices. The findings show that the cost and complexity dimension has the most significant (negative) impact on the perceived behavioral control over EA practices. This may be the reason why most of the private companies in Sri Lanka have ignored environmentally friendly practices, including EA [

39], which has led to the observation of vast environmental pollution in the country.

The application of PLS-SEM in the EA context is also a novel contribution. This is one of the first studies that employees the PLS-SEM approach in order to identify socio-psychological parameters related to EA implementation. Moreover, we performed an MGA using a permutation procedure, which also fills a methodological gap in the EA literature. In addition, our study expands the current empirical evidence by examining the managerial perspective on the implementation of the EA in a developing country. This is important because most of the current empirical evidence is based on developed countries and, therefore, lacks the transferability of those findings to the developing world.

6.2. Managerial and Policy Implications

This study provides important implications for managers and regulatory authorities. Our findings indicate that subjective norms have a greater influence on the managers’ intention to engage in EA practices. This implies that there is increasing pressure from stakeholders towards environmental preservation. Establishing environmentally friendly policies would, therefore, bring companies with competitive advantages. However, most managers perceive EA practices as more expensive and as increasing the complexity of the accounting and reporting systems, which may require additional resources and time. Even so, the benefits of EA practices should be understood not as short term, but as long term. Accounting for the impact of business operations on the natural environment not only provides stakeholders with a holistic perspective of business operations, but also helps managers to develop strategies to mitigate such impacts and, thus, improve financial performance.

The findings of this research provide regulators with important insights into how rules and regulations can encourage managers to implement EA practices within their companies. Our results indicate that perceived regulatory pressure has a significant positive influence on managers’ intention to engage in EA practices through perceived behavioral control. Regulators such as the Central Environmental Authority, the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka, and the Board of Investment can formulate rules, regulations, and standards and provide necessary guidance for companies to make it easier to implement EA practices. EA practices in Sri Lanka would also be encouraged through effective planning and development programs that enhance managers’ sensitivity towards EA practices.

6.3. Limitations

We believe that there are at least two limitations in this study. First, the overall model can explain only about half of the variance of managerial intention to engage in EA practice, which implies that certain other factors are responsible for the majority of the variance in the managers’ intention. Moreover, this study does not explore the actual implementation of EA practices within Sri Lankan companies. Future studies could incorporate more external and controlling factors that can fully explain managers’ intention to engage in EA practices, and this study could be extended to examine the actual implementation of EA practices. Second, despite its advantages and widespread use, there are always certain limitations to the questionnaire survey that affect the validity and reliability of the information collected. With their busy work schedules, whether the top managers completed the questionnaires themselves is questionable, which leaves the doubt as to whether this information truly reflects the managers’ perspectives on EA practices. In addition, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution, as the managers’ responses may not reflect their real attitudes, perceptions, and intention towards EA practices as a result of “greenwashing”. Managers may perceive the disclosure of their actual intent as a threat and thereby overstate the actual intention to engage in EA practices. These problems can be overcome by an alternative research design in which information on managers’ intention to engage in EA practice can be obtained through interviews or telephone conversations. Such methods may provide a more realistic view of managers’ intentions and attitudes towards EA practices.

6.4. Notes

Recent incidents, such as a garbage dump disaster that killed more than 15 people, rapid deforestation of one of the large national parks (Wilpattu), and chronic kidney disease, which is suspected to be caused by the heavy use of pesticide chemicals, caught the public attention regarding environmental problems in Sri Lanka. The public concern about these problems was reflected in the deluge of criticism and opinions shared in social media.