Changes in Sustainability Priorities in Organisations due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Averting Environmental Rebound Effects on Society

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Organisation characteristics;

- Sustainability questions, including the priorities prior to and during the COVID-19 outbreak;

- Internal and external factors affecting the organisation;

- Impacts on system elements due to COVID-19;

- Sustainability and digitalisation training and engagement.

2.1. Limitations of the Methods

3. Results

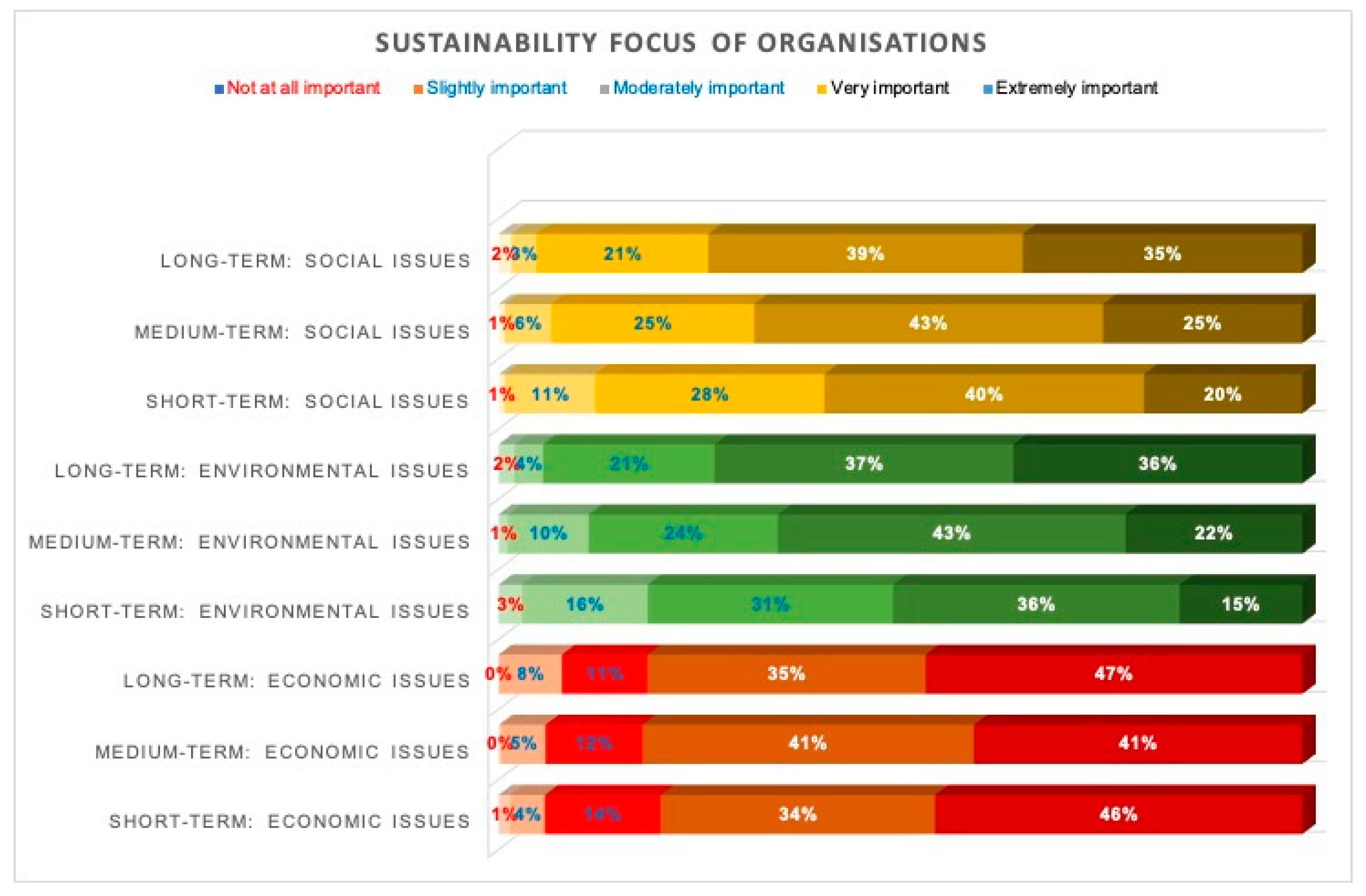

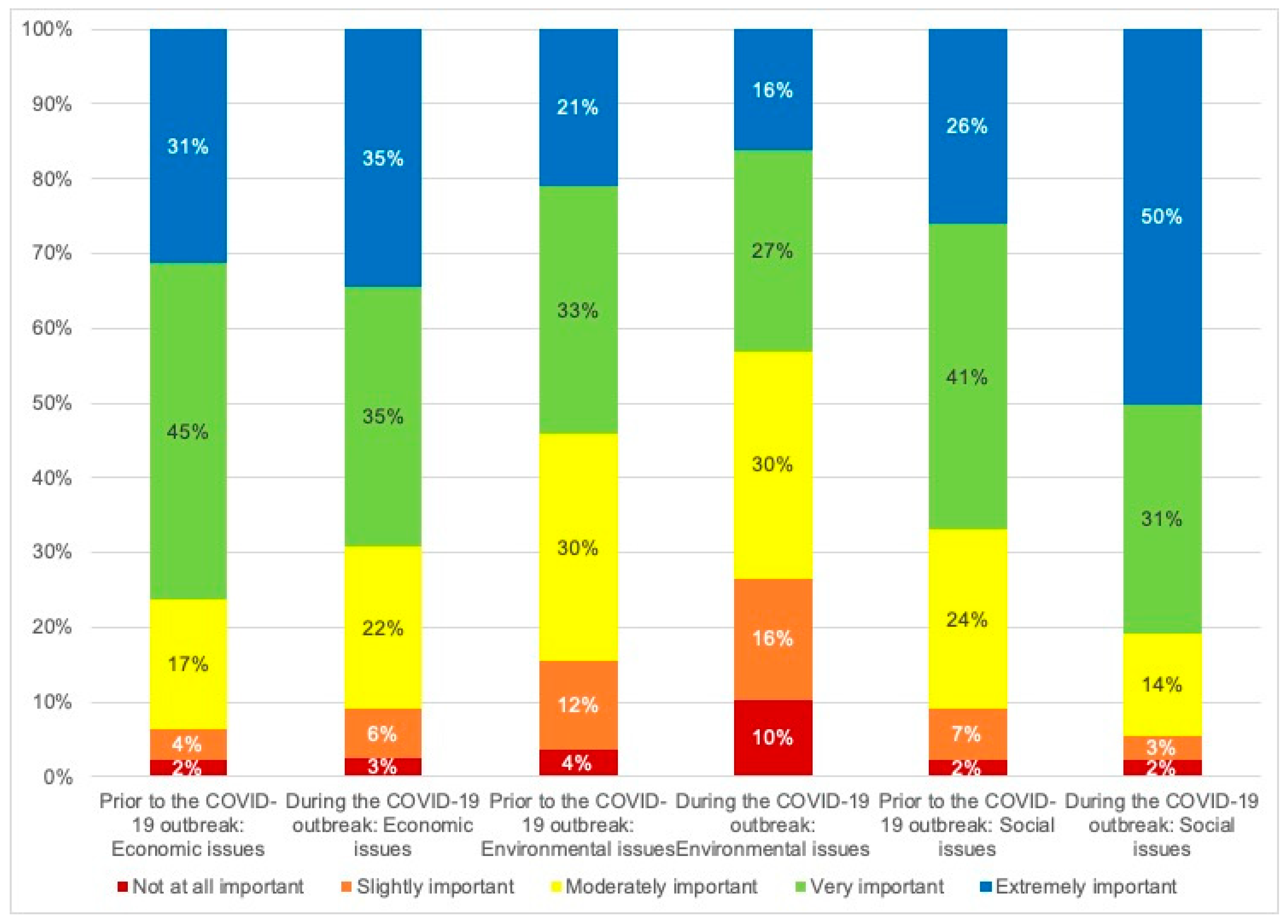

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

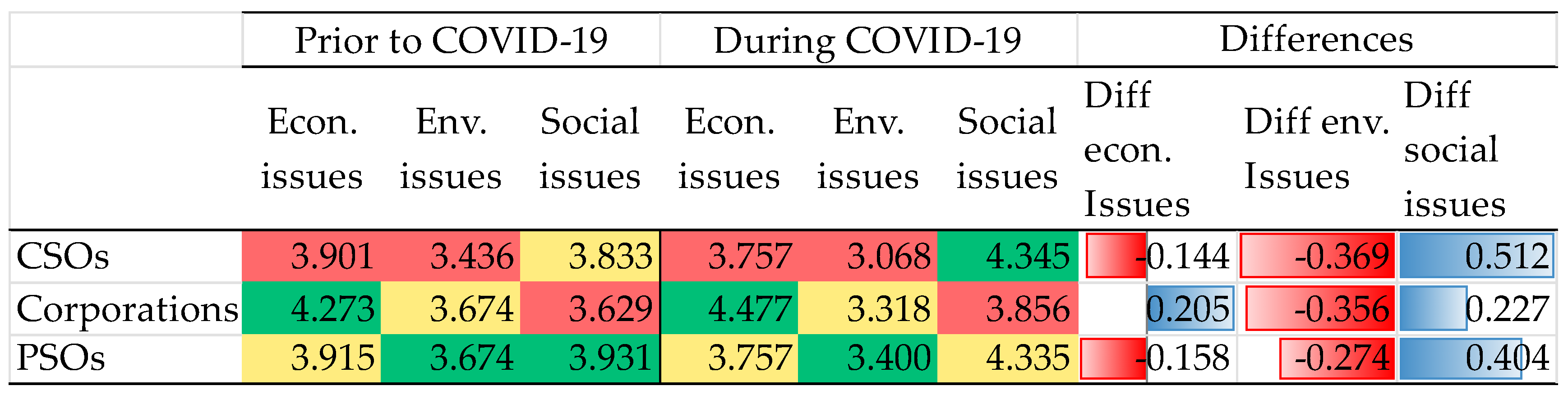

3.2. Organisation Type Analyses

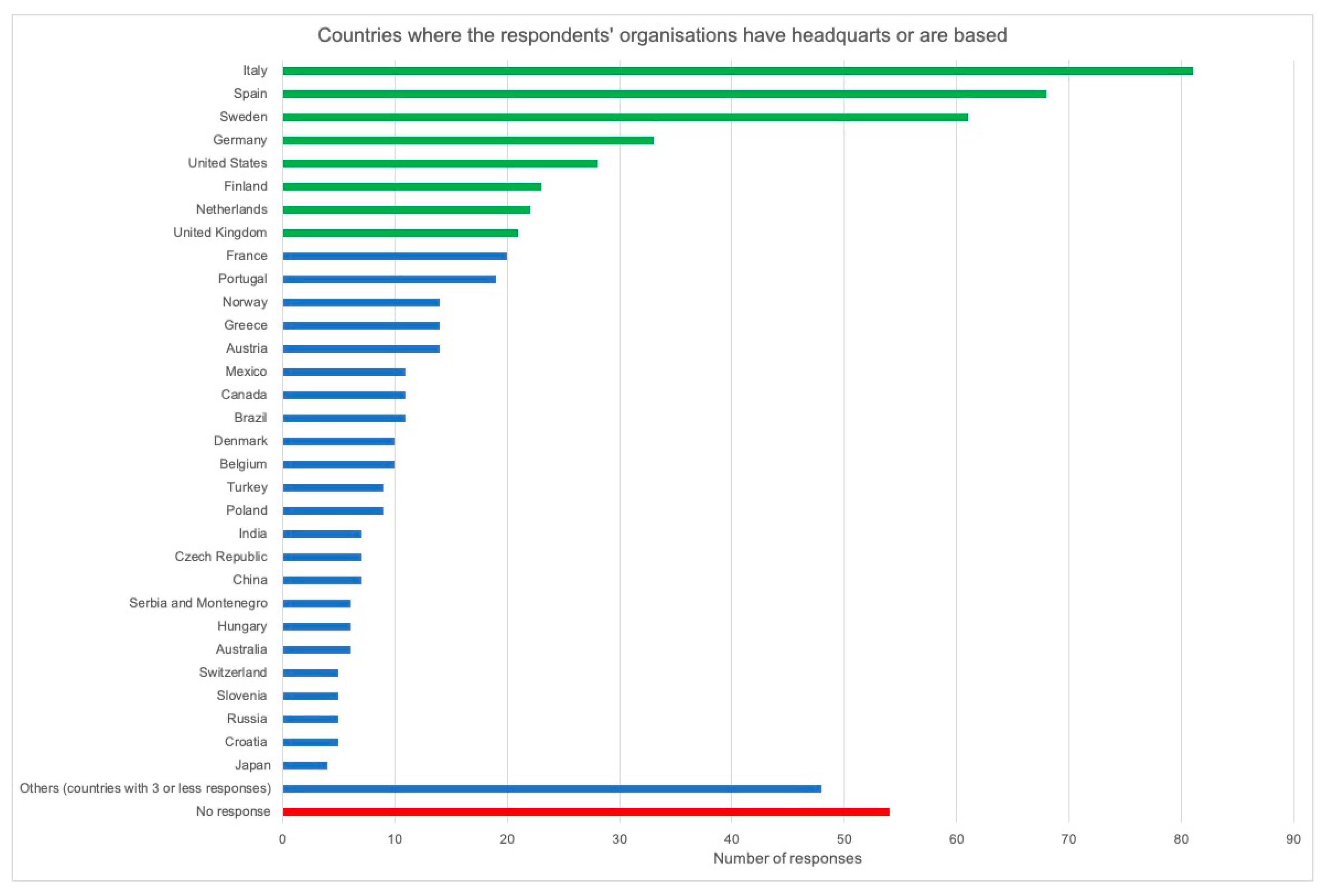

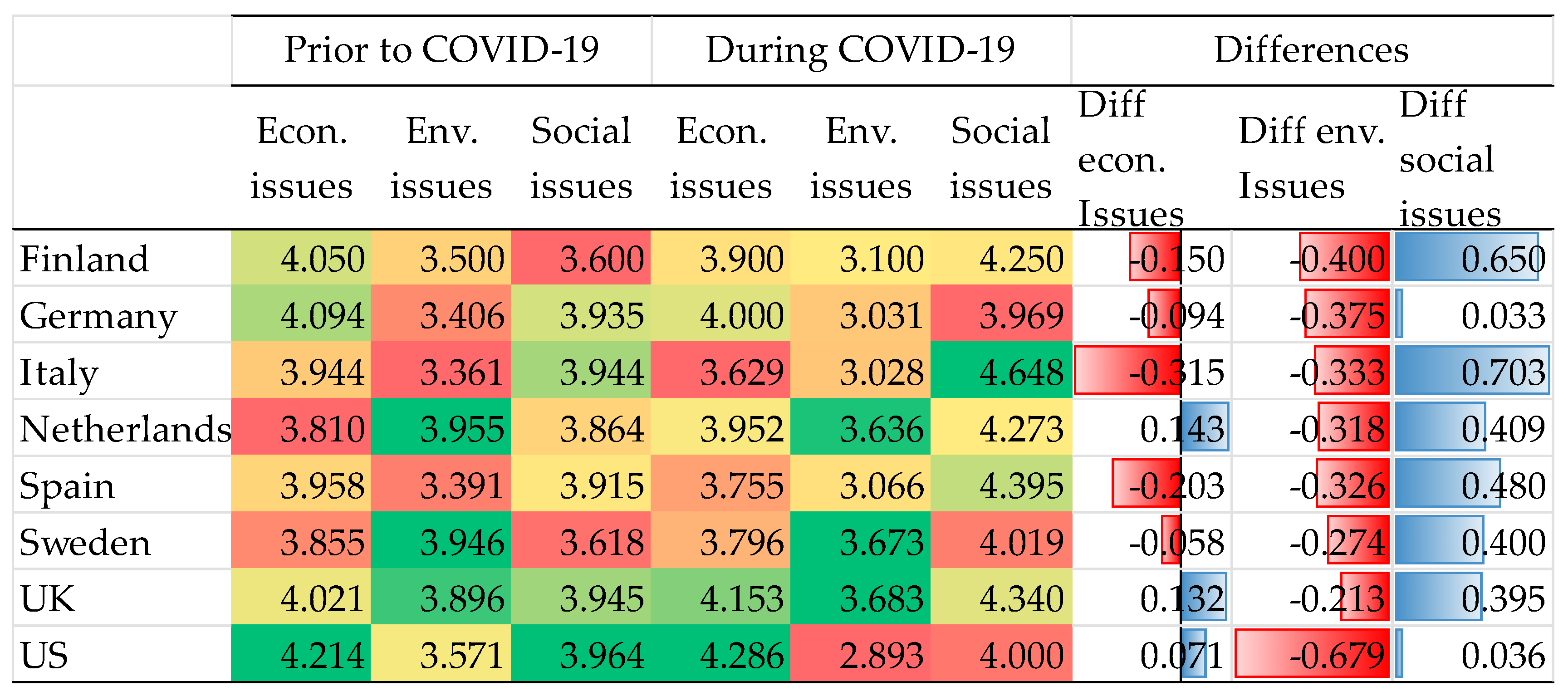

3.3. Organisation Headquarter/Base Country Analyses

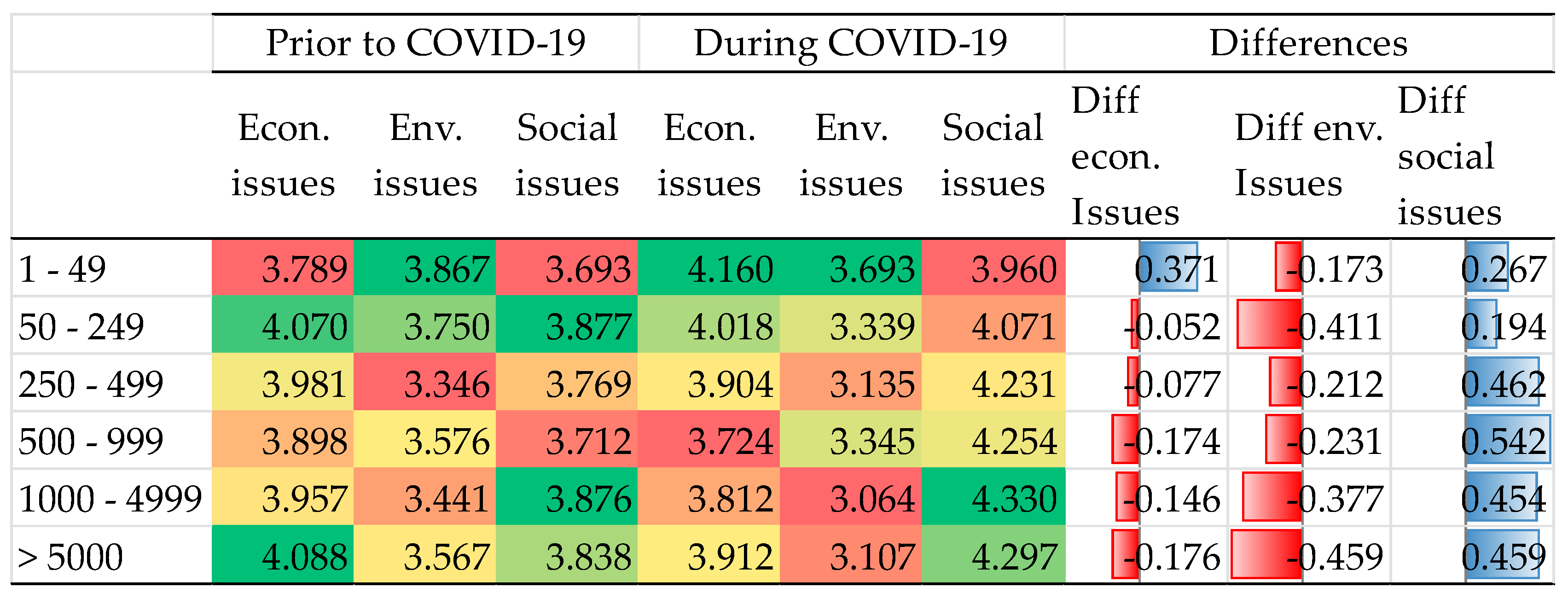

3.4. Organisation Size

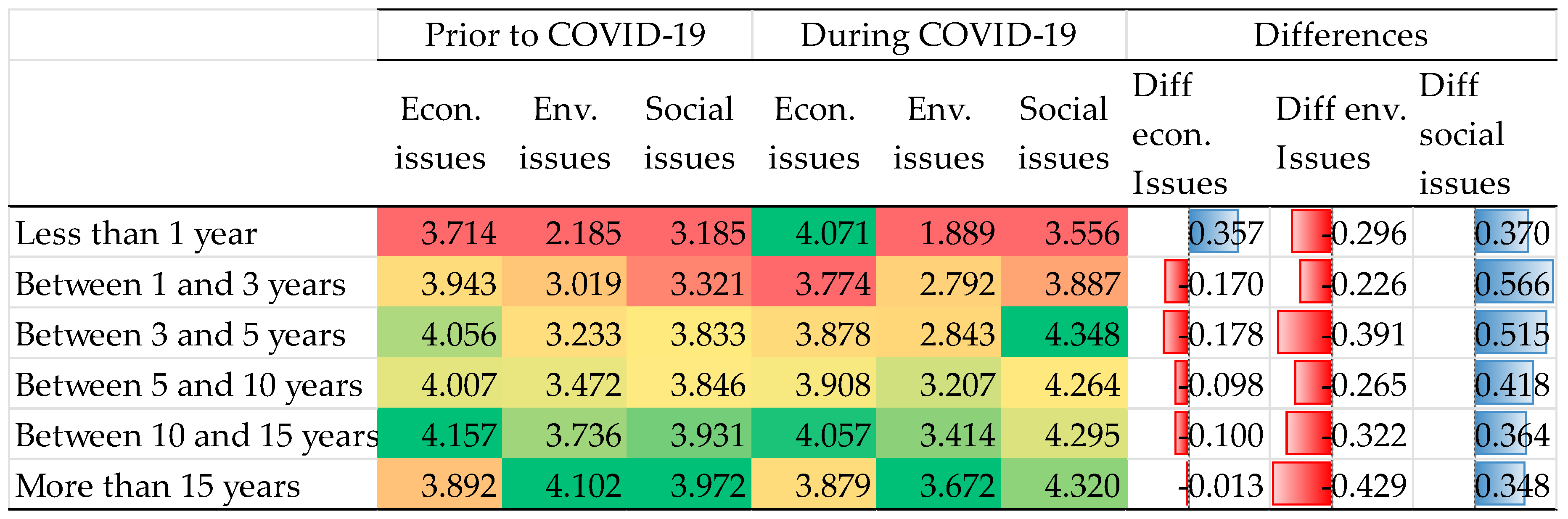

3.5. Years Working with Sustainability

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muhammad, S.; Long, X.; Salman, M. COVID-19 pandemic and environmental pollution: A blessing in disguise? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saadat, S.; Rawtani, D.; Hussain, C.M. Environmental perspective of COVID-19. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Reports. April 1 2020. WHO Situat. Rep. 2020, 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, A.P.; Masago, Y.; Hijioka, Y. COVID-19 and surface water quality: Improved lake water quality during the lockdown. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 731, 139012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Ruiz, C.; Moneva-Abadía, J.M. Special issue on “social responsibility accounting and reporting in times of “sustainability downturn/crisis”. Rev. Contab. Account. Rev. 2011, 14, 187–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cepiku, D.; Mussari, R.; Giordano, F. Local governments managing austerity: Approaches, determinants and impact. Public Adm. 2016, 94, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G.; Theotokas, I. The Effect of Financial Crisis in Corporate Social Responsibility Performance. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2011, 3, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Ruano, M.A.; Sanchez-Alcalde, L. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on the Environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutheil, F.; Baker, J.S.; Navel, V. COVID-19 as a factor influencing air pollution? Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global Energy Review 2020; IEA: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas, G.; Siciliano, B.; França, B.B.; da Silva, C.M.; Arbilla, G. The impact of COVID-19 partial lockdown on the air quality of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 139085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, C. Is Coronavirus Reducing Noise Pollution? Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinero/2020/04/19/is-coronavirus-reducing-noise-pollution/#55570287766f (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Researchgate COVID-19 Research Community. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/community/COVID-19 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Google Scholar. COVID-19 Online Search. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=es&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=covid+19&btnG= (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Frontiers. Coronavirus Knowledge Hub. Available online: https://coronavirus.frontiersin.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2020).

- Scott, W.R.; Davis, G.F. Organization: Overview, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 16, ISBN 9780080970868. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, C.R. Sustainability and Sustainable Development. Top. Environ. Rhetor. 2018, 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.R. Organizational Theory, Design, and Change, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, Englad, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth, P.; Bagheri, A. Navigating towards sustainable development: A system dynamics approach. Futures 2006, 38, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes, R.; Sanchez, R. Autopoiesis theory and organization: An overview. In Advanced Series in Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 6, pp. 3–25. ISBN 9781848558328. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Developing Collaborative & Sustainable Organisations. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Daley, C. How organisations learn. Nurs. Manag. 2008, 15, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, L.; Avery, G.C. Transforming Organisations towards Sustainable Practices. Int. J. Interdiscipl. Soc. Sci. 2009, 4, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Lawler, E.E.I.; Hackman, J.R. Behavior in Organizations; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1975; ISBN 0 07 050527 6. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, R.D. Strategic Management and Organisational Dynamics; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 1993; ISBN 0 273 600982. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). UN Agenda 21; United Nations: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, C.O.J.; Schmidheiny, S.; Watts, P. Walking the Talk. The Business Case for Sustainable Development; Greenleaf Publishing: Sheffield, UK, 2002; ISBN 1 874719 50 0. [Google Scholar]

- Lyth, A.; Baldwin, C.; Davison, A.; Fidelman, P.; Booth, K.; Osborne, C. Valuing third sector sustainability organisations–qualitative contributions to systemic social transformation. Local Environ. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dururu, J.; Anderson, C.; Bates, M.; Montasser, W.; Tudor, T. Enhancing engagement with community sector organisations working in sustainable waste management: A case study. Waste Manag. Res. 2015, 33, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Garcia, I. Scrutinizing Sustainability Change and Its Institutionalization in Organizations. Front. Sustain. 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.A.d.S.; de Francisco, A.C. Organizational sustainability practices: A study of the firms listed by the Corporate Sustainability Index. Sustainability 2018, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, R. Proposing a Definition and a Framework of Organisational Sustainability: A Review of Efforts and a Survey of Approaches to Change. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomas, T.E.; Lamm, E. Legitimacy and Organizational Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraud, R.J.; Williams, P.A.; Sehgal, A.; Ponnusamy, E.; Phillips, A.K.; Manley, J.B. Implementing green chemistry in chemical manufacturing: A survey report. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekincioglu, O.; Gurgun, A.P.; Engin, Y.; Tarhan, M.; Kumbaracibasi, S. Approaches for sustainable cement production-A case study from Turkey. Energy Build. 2013, 66, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunse, K.; Vodicka, M.; Schönsleben, P.; Brülhart, M.; Ernst, F.O. Integrating energy efficiency performance in production management-Gap analysis between industrial needs and scientific literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Barker, M.; Mouasher, A. Is it even espoused? An exploratory study of commitment to sustainability as evidenced in vision, mission, and graduate attribute statements in Australian universities. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Banai, C.; Theis, T.L. Quantitative analysis of factors affecting greenhouse gas emissions at institutions of higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, M.; Gonçalves, M.D.S.; Kiperstok, A. Water conservation as a tool to support sustainable practices in a Brazilian public university. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Farneti, F. GRI Sustainability Reporting by Australian Public Sector Organizations. Public Money Manag. 2008, 28, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S.; Jacobs, K.; Park, Y.J. Driving public sector environmental reporting: The disclosure practices of Australian Commonwealth Departments. Public Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 631–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-feijóo Souto, B. Crisis and Corporate Social Responsibility: Threat or Opportunity? Int. J. Econ. Sci. Appl. Res. 2009, II, 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Arevalo, J.A.; Aravind, D. The impact of the crisis on corporate responsibility: The case of UN global compact participants in the USA. Corp. Gov. 2010, 10, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radler, B.T.; Love, G.D. Behind the Scenes in Integrative Health Science: Understanding and Negotiating Data Management Challenges. In The Oxford Handbook of Integrative Health Science; Ryff, C.D., Krueger, R.F., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 22–34. ISBN 9780190676384. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Software 2015; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Type of Organisation | N | Mean Rank | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | CSOs | 282 | 282.13 | *** |

| Corporations | 132 | 345.91 | ||

| PSOs | 177 | 280.88 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | CSOs | 282 | 272.90 | *** |

| Corporations | 132 | 320.00 | ||

| PSOs | 175 | 311.76 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | CSOs | 281 | 298.01 | ** |

| Corporations | 132 | 262.71 | ||

| PSOs | 174 | 311.26 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | CSOs | 280 | 267.39 | *** |

| Corporations | 132 | 386.03 | ||

| PSOs | 173 | 263.47 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | CSOs | 281 | 272.07 | *** |

| Corporations | 132 | 310.95 | ||

| PSOs | 175 | 318.11 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | CSOs | 281 | 311.69 | *** |

| Corporations | 132 | 238.09 | ||

| PSOs | 173 | 306.23 |

| Variable | Country | N | Mean Rank | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | Finland | 20 | 154.525 | 0.297 |

| Germany | 32 | 162.844 | ||

| Italy | 71 | 155.092 | ||

| Netherlands | 21 | 134.190 | ||

| Spain | 61 | 147.230 | ||

| Sweden | 55 | 136.600 | ||

| UK | 17 | 177.294 | ||

| US | 28 | 179.500 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | Finland | 20 | 148.550 | ** |

| Germany | 32 | 143.297 | ||

| Italy | 72 | 134.042 | ||

| Netherlands | 22 | 184.341 | ||

| Spain | 62 | 142.403 | ||

| Sweden | 56 | 185.973 | ||

| UK | 16 | 171.719 | ||

| US | 28 | 154.714 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | Finland | 20 | 137.475 | 0.336 |

| Germany | 31 | 156.484 | ||

| Italy | 72 | 158.382 | ||

| Netherlands | 22 | 156.932 | ||

| Spain | 61 | 159.172 | ||

| Sweden | 55 | 128.355 | ||

| UK | 16 | 171.094 | ||

| US | 28 | 167.929 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | Finland | 20 | 147.050 | ** |

| Germany | 32 | 160.875 | ||

| Italy | 70 | 132.614 | ||

| Netherlands | 21 | 159.000 | ||

| Spain | 61 | 144.680 | ||

| Sweden | 54 | 145.509 | ||

| UK | 17 | 198.882 | ||

| US | 28 | 188.607 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | Finland | 20 | 144.925 | ** |

| Germany | 32 | 138.813 | ||

| Italy | 72 | 137.271 | ||

| Netherlands | 22 | 180.909 | ||

| Spain | 62 | 147.581 | ||

| Sweden | 55 | 184.991 | ||

| UK | 16 | 190.250 | ||

| US | 28 | 132.339 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | Finland | 20 | 167.900 | *** |

| Germany | 32 | 119.828 | ||

| Italy | 71 | 185.282 | ||

| Netherlands | 22 | 155.659 | ||

| Spain | 61 | 161.057 | ||

| Sweden | 54 | 122.204 | ||

| UK | 16 | 163.000 | ||

| US | 28 | 127.018 |

| Variable | Size (employees) | N | Mean Rank | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | 1–49 | 76 | 253.447 | 0.122 |

| 50–249 | 57 | 307.289 | ||

| 250–499 | 52 | 289.577 | ||

| 500–999 | 59 | 274.771 | ||

| 1000–4999 | 188 | 287.638 | ||

| >5000 | 148 | 313.291 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | 1–49 | 75 | 342.887 | *** |

| 50–249 | 56 | 322.688 | ||

| 250–499 | 52 | 256.212 | ||

| 500–999 | 59 | 288.051 | ||

| 1000–4999 | 186 | 267.882 | ||

| >5000 | 150 | 289.333 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | 1–49 | 75 | 271.907 | 0.714 |

| 50–249 | 57 | 293.825 | ||

| 250–499 | 52 | 274.731 | ||

| 500–999 | 59 | 271.949 | ||

| 1000–4999 | 185 | 299.230 | ||

| >5000 | 148 | 292.882 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | 1–49 | 75 | 328.407 | * |

| 50–249 | 56 | 306.446 | ||

| 250–499 | 52 | 281.337 | ||

| 500–999 | 58 | 251.500 | ||

| 1000–4999 | 186 | 275.401 | ||

| >5000 | 147 | 291.105 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | 1–49 | 75 | 355.687 | *** |

| 50–249 | 56 | 305.268 | ||

| 250–499 | 52 | 281.192 | ||

| 500–999 | 58 | 309.112 | ||

| 1000–4999 | 187 | 265.273 | ||

| >5000 | 149 | 273.993 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | 1–49 | 75 | 240.920 | ** |

| 50–249 | 56 | 253.500 | ||

| 250–499 | 52 | 291.596 | ||

| 500–999 | 59 | 289.305 | ||

| 1000–4999 | 185 | 307.654 | ||

| >5000 | 148 | 298.561 |

| Variable | Years Working with Sustainability | N | Mean Rank | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | Less than 1 year | 28 | 263.518 | 0.176 |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 53 | 284.783 | ||

| Between 3 and 5 years | 90 | 301.656 | ||

| Between 5 and 10 years | 144 | 297.347 | ||

| Between 10 and 15 years | 89 | 319.843 | ||

| More than 15 years | 176 | 270.369 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | Less than 1 year | 27 | 102.037 | *** |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 53 | 210.151 | ||

| Between 3 and 5 years | 90 | 234.567 | ||

| Between 5 and 10 years | 144 | 268.122 | ||

| Between 10 and 15 years | 87 | 313.971 | ||

| More than 15 years | 177 | 375.153 | ||

| Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | Less than 1 year | 27 | 194.519 | *** |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 53 | 214.792 | ||

| Between 3 and 5 years | 90 | 285.867 | ||

| Between 5 and 10 years | 143 | 293.364 | ||

| Between 10 and 15 years | 87 | 302.328 | ||

| More than 15 years | 176 | 315.673 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Economic issues | Less than 1 year | 28 | 318.036 | 0.568 |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 53 | 267.547 | ||

| Between 3 and 5 years | 90 | 283.728 | ||

| Between 5 and 10 years | 142 | 282.708 | ||

| Between 10 and 15 years | 88 | 309.898 | ||

| More than 15 years | 174 | 284.851 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Environmental issues | Less than 1 year | 27 | 123.056 | *** |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 53 | 235.887 | ||

| Between 3 and 5 years | 89 | 234.669 | ||

| Between 5 and 10 years | 145 | 283.231 | ||

| Between 10 and 15 years | 87 | 317.075 | ||

| More than 15 years | 177 | 350.096 | ||

| During the COVID-19 outbreak: Social issues | Less than 1 year | 27 | 186.019 | *** |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 53 | 238.472 | ||

| Between 3 and 5 years | 89 | 310.949 | ||

| Between 5 and 10 years | 144 | 299.514 | ||

| Between 10 and 15 years | 88 | 290.432 | ||

| More than 15 years | 175 | 298.011 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barreiro-Gen, M.; Lozano, R.; Zafar, A. Changes in Sustainability Priorities in Organisations due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Averting Environmental Rebound Effects on Society. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125031

Barreiro-Gen M, Lozano R, Zafar A. Changes in Sustainability Priorities in Organisations due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Averting Environmental Rebound Effects on Society. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125031

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarreiro-Gen, Maria, Rodrigo Lozano, and Afnan Zafar. 2020. "Changes in Sustainability Priorities in Organisations due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Averting Environmental Rebound Effects on Society" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125031

APA StyleBarreiro-Gen, M., Lozano, R., & Zafar, A. (2020). Changes in Sustainability Priorities in Organisations due to the COVID-19 Outbreak: Averting Environmental Rebound Effects on Society. Sustainability, 12(12), 5031. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125031