Using a Two-Stage DEA Model to Measure Tourism Potentials of EU Countries and Western Balkan Countries: An Approach to Sustainable Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Methodology

3.2. Data Collection and Descriptive Statistics

- ▪

- Average receipts per arrival. International tourism receipts are expenditures by international inbound visitors, including payments to national carriers for international transport. These receipts include any other prepayment made for goods or services received in the destination country.

- ▪

- T&T industry employment, as a percentage of total employment.

- ▪

- Sustainability of travel and tourism industry development, which shows how effective are a government’s efforts to ensure that the T&T sector is being developed in a sustainable way (1 = very ineffective, development of the sector does not take into account issues related to environmental protection and sustainable development; 7 = very effective, issues related to environmental protection and sustainable development are at the core of the government’s strategy).

- ▪

- Sustainability of travel and tourism industry development;

- ▪

- Travel and tourism industry share of GDP;

- ▪

- Travel and tourism industry share of employment;

- ▪

- Number of international tourist arrivals;

- ▪

- Amount of international tourism inbound receipts;

- ▪

- Travel and tourism government expenditure;

- ▪

- Visa requirements index, measures to what extent a destination country is facilitating inbound tourism through its visa policy;

- ▪

- Rate of use (tourist attendances/rooms);

- ▪

- Number of World Heritage cultural sites;

- ▪

- Number of World Heritage natural sites.

4. Research Results

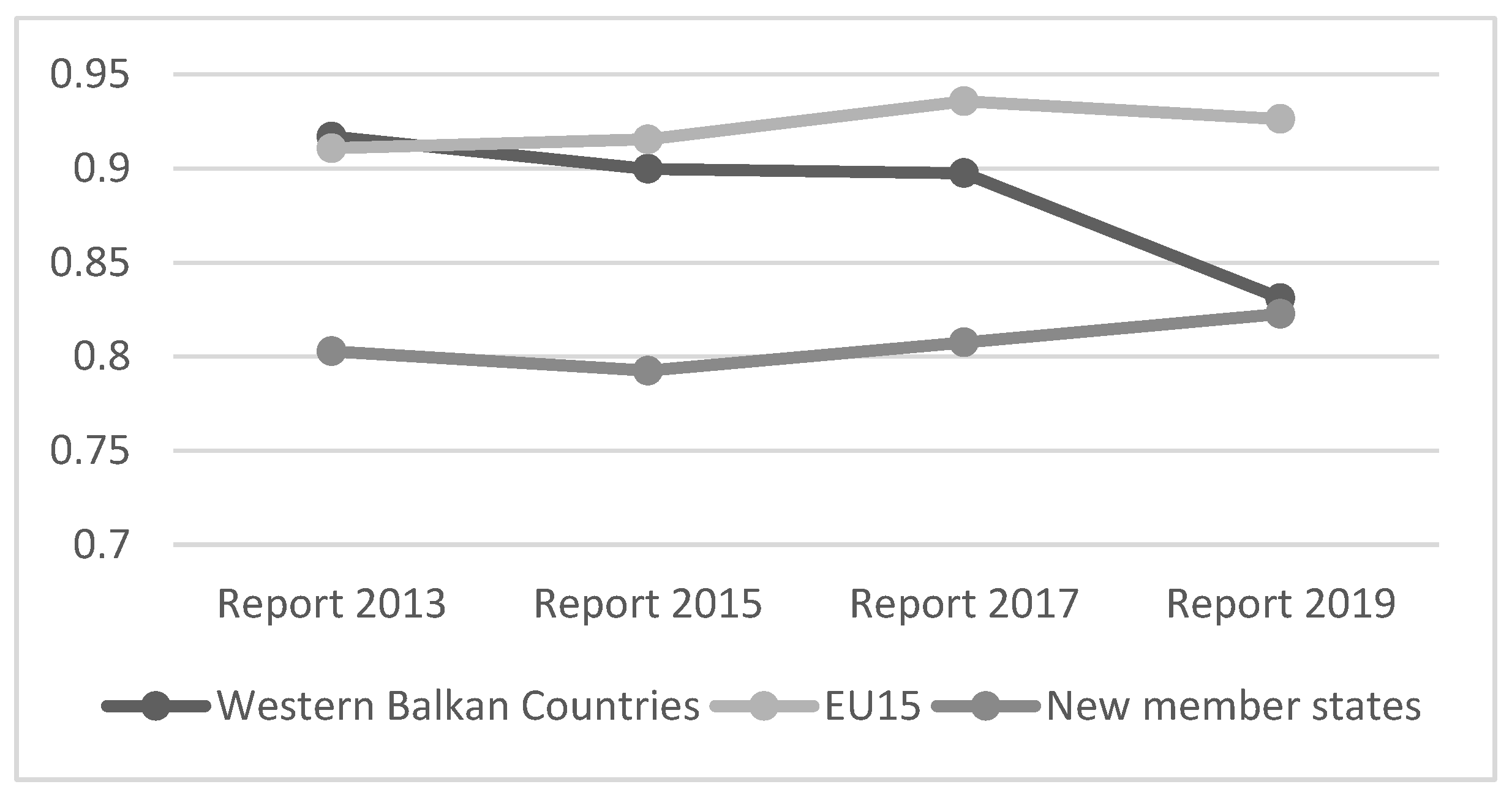

4.1. Data Envelopment Analysis Results

4.2. Tobit Regression Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, P.W.; Fennell, D.A. Creating a Sustainable Equilibrium between Mountain Communities and Tourism Development. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2002, 27, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, C.-H. Evaluation and Drive Mechanism of Tourism Ecological Security Based on the DPSIR-DEA Model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Tang, G.; Yan, B.; Xiao, X. Eco-efficiency and Its Determinants at a Tourism Destination: A Case Study of Huangshan National Park, China. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cracolici, M.F.; Nijkamp, P.; Rietveld, P. Assessment of Tourist Competitiveness by Analysing Destination Efficiency. Tinbergen Inst. Discuss. Pap. 2006. Available online: https://papers.tinbergen.nl/06097.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Dangi, T.B.; Jamal, T. An Integrated Approach to “Sustainable Community-Based Tourism”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, A. Second Stage DEA: Comparison of Approaches for Modeling the DEA Score. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 181, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Z. Tourism Eco-efficiency of Chinese Coastal Cities—Analysis Based on the DEA-Tobit Model. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 148, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaabouni, S. China’s Regional Tourism Efficiency: A Two-Stage Double Bootstrap Data Envelopment Analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 11, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro Jurado, E.; Tejada Tejada, M.; Almeida Garcia, F.; Cabello Gonzalez, J.; Cortes Macias, R.; Delgado Pena, J. Carrying Capacity Assessment for Tourist Destinations. Methodology for the Creation of Synthetic Indicators Applied in a Coastal Area. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, S. Sustainable Tourism. Am. Int. J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 1, 50–56. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable Tourism Development: A Critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfani, S.; Sedaghat, M.; Maknoon, R.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E. Sustainable Tourism: A Comprehensive Literature Review on Frameworks and Applications. Econ. Res. 2015, 28, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G. Sustainable Tourism Innovation: Challenging Basic Assumptions. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2008, 8, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, K.S. Sustainable Tourism Certification and State Capacity: Keep it Local, Simple and Fuzzy. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2011, 5, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.H. Conventional or sustainable tourism? No room for choice. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, I.; Rao, J. Aligning Service Strategy through Super-Measure Management. Acad. Manag. Exec. 2002, 16, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M. Strategy Development in Tourism Destinations: A DEA Approach. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2004, 4, 52–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Tsai, B.; Liou, G.; Hsieh, C. Efficiency Assessment of Inbound Tourist Service Using Data Envelopment Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hsieh, C.; Lin, S.; Shih, M. Two-Stage Evaluation of International Tourist Hotels in Taiwan Using Data Envelopment Analysis. J. Interdiscip. Math. 2013, 16, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Hsiao, C.; Jang, H. Measuring the Operational Performance of International Tourist Hotels in Taiwan: A Simar and Wilson Approach. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on New Trends in Information Science and Service Science, Gyeongju, South Korea, 11–13 May 2010; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/5488559 (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Škrinjarić, T. Evaluation of Environmentally Conscious Tourism Industry: Case of Croatian Counties. Tourism 2018, 66, 254–268. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Guo, Q.; Wu, D.; Yin, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, T. Spatial Characteristics of Development Efficiency for Urban Tourism in Eastern China: A Case Study of Six Coastal Urban Agglomerations. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 1175–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosetti, V.; Cassinelli, M.; Lanza, A. Benchmarking in Tourism Destination, Keeping in Mind the Sustainable Paradigm. NRB—Natural Resources Management Working Paper. 2006. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/12156/1/wp060012.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Tomić, S.; Marcikić Horvat, А. Evaluation of Efficiency in Tourism Industry. 3rd International Thematic Monograph—Thematic Proceedings, Modern Management Tools and Economy of Tourism Sector in Present Era, Association of Economists and Managers of the Balkans in cooperation with the Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality. 2018, pp. 289–298. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/424574373/6-thematic-monograph-2018-final?secret_password=bZ5HV6NnK73FRIkBWRDZ#fullscreen&from_embed (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Assaf, A.G. Benchmarking the Asia Pacific Tourism Industry: A Bayesian Combination of DEA and Stochastic Frontier. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1122–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J.C.; Mendoza, C.; Román, C. A DEA Travel–Tourism Competitiveness Index. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 130, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, S.; Hadad, Y.; Malul, M.; Rosenboim, M. The economic Efficiency of the Tourism Industry: A Global Comparison. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmaczewska, J. Tourism Interest and the Efficiency of Its Utilisation Based on the Example of the EU Countries. Acta Sci. Pol. Oeconomia 2014, 13, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, G.; Luo, Y.; Liang, L. Efficiency Evaluation of Tourism Industry with Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA): A Case Study in China. J. China Tour. Res. 2011, 7, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botti, L.; Peypoch, N.; Robinot, E.; Solonandrasana, B. Tourism destination competitiveness: The French regions case. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 21, 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, E. Regional Scale Efficiency Evaluation by Input-oriented Data Envelopment Analysis of Tourism Sector. Int. J. Acad. Res. Environ. Geogr. 2014, 1, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal-Kurt, H. Measuring Tourism Efficiency of European Countries by Using Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. Sci. J. 2017, 13, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1957, 3, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 6, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 9, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J. Using Least Squares and Tobit in Second Stage DEA Efficiency Analyses. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 197, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grmanova, E.; Strunz, H. Efficiency of Insurance Companies: Application of DEA and Tobit Analyses. J. Int. Stud. 2017, 10, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2013: Reducing Barriers to Economic Growth and Job Creation. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TT_Competitiveness_Report_2013.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2015: Growth through Shocks. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/TT15/WEF_Global_Travel&Tourism_Report_2015.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2017: Paving the Way for a More Sustainable and Inclusive Future. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2017_web_0401.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- World Economic Forum. The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019: Traveling and Tourism at a Tipping Point. Available online: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_TTCR_2019.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Shieh, H.S.; Hu, J.L.; Liu, T.J. An Environmental-Adjusted Dynamic Efficiency Analysis of International Tourist Hotels in Taiwan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1749–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | Year | Statistics | T&T Government Expenditure | T&T Industry Share of Employment | Average Receipt per Arrival | Sustainability of T&T Industry Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Balkan | Report 2019 | Max | 4.00 | 8.00 | 898.74 | 4.90 |

| Min | 0.50 | 1.80 | 415.52 | 3.00 | ||

| St. dev. | 1.41 | 2.84 | 225.48 | 0.79 | ||

| Average | 1.92 | 4.38 | 656.65 | 3.82 | ||

| Report 2013 | Max | 3.90 | 7.60 | 5.30 | 1602.19 | |

| Min | 0.80 | 1.20 | 3.50 | 585.97 | ||

| St. dev. | 1.29 | 2.87 | 0.73 | 451.62 | ||

| Average | 1.94 | 3.56 | 4.08 | 972.80 | ||

| EU 15 | Report 2019 | Max | 8.10 | 12.70 | 4352.33 | 5.80 |

| Min | 2.20 | 2.00 | 543.33 | 3.90 | ||

| St. dev. | 1.77 | 2.92 | 961.13 | 0.49 | ||

| Average | 3.94 | 5.42 | 1191.99 | 5.01 | ||

| Report 2013 | Max | 8.00 | 8.90 | 5.50 | 8862.88 | |

| Min | 2.10 | 1.70 | 3.40 | 598.58 | ||

| St. dev. | 1.70 | 2.27 | 0.64 | 2043.36 | ||

| Average | 3.56 | 3.74 | 4.72 | 1541.10 | ||

| New member states | Report 2019 | Max | 11.60 | 11.40 | 915.58 | 5.20 |

| Min | 1.40 | 1.90 | 383.65 | 3.50 | ||

| St. dev. | 3.16 | 2.96 | 177.69 | 0.49 | ||

| Average | 4.68 | 4.65 | 613.86 | 4.42 | ||

| Report 2013 | Max | 11.30 | 14.90 | 4.80 | 16629.69 | |

| Min | 1.40 | 1.50 | 3.20 | 468.67 | ||

| St. dev. | 3.06 | 4.06 | 0.58 | 4382.43 | ||

| Average | 4.81 | 5.43 | 4.10 | 2080.10 |

| Country | Report 2019 | Report 2017 | Report 2015 | Report 2013 | Average Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | 0.83 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| Austria | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Belgium | 0.79 | 0.89 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.87 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 0.81 |

| Bulgaria | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.71 |

| Croatia | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Cyprus | 0.84 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 0.88 | 0.86 |

| The Czech Republic | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.80 |

| Denmark | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.87 |

| Estonia | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Finland | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| France | 0.91 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.92 | 0.92 |

| Germany | 0.97 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.98 |

| Greece | 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.87 |

| Hungary | 0.74 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.73 |

| Ireland | 0.91 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

| Italy | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.68 |

| Latvia | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.85 |

| Lithuania | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.71 |

| Luxembourg | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Malta | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| Montenegro | 0.96 | 0.99 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 0.98 |

| The Netherlands | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.95 |

| North Macedonia | 0.64 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| Poland | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.74 |

| Portugal | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.91 | 0.91 | 0.95 |

| Romania | 0.67 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.67 | 0.65 |

| Serbia | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Slovakia | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.76 |

| Slovenia | 0.92 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.81 |

| Spain | 0.83 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 0.88 |

| Sweden | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| The United Kingdom | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 0.93 | 0.92 |

| Variable | Coefficient | z-Statistic |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.149488 *** | 2.8005 |

| Sustainability of travel and tourism industry development | 0.133326 *** | 14.9574 |

| T&T industry Share of GDP | 0.013807 *** | 5.8257 |

| International tourist arrivals | 0.000001 *** | 3.3449 |

| International tourism inbound receipts | 0.000003 *** | 3.0045 |

| T&T government expenditure | −0.012822 *** | −4.4239 |

| Visa requirements | 0.004835 *** | 3.7652 |

| Rate of use | 0.000229 ** | 2.1456 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Radovanov, B.; Dudic, B.; Gregus, M.; Marcikic Horvat, A.; Karovic, V. Using a Two-Stage DEA Model to Measure Tourism Potentials of EU Countries and Western Balkan Countries: An Approach to Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124903

Radovanov B, Dudic B, Gregus M, Marcikic Horvat A, Karovic V. Using a Two-Stage DEA Model to Measure Tourism Potentials of EU Countries and Western Balkan Countries: An Approach to Sustainable Development. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124903

Chicago/Turabian StyleRadovanov, Boris, Branislav Dudic, Michal Gregus, Aleksandra Marcikic Horvat, and Vincent Karovic. 2020. "Using a Two-Stage DEA Model to Measure Tourism Potentials of EU Countries and Western Balkan Countries: An Approach to Sustainable Development" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124903

APA StyleRadovanov, B., Dudic, B., Gregus, M., Marcikic Horvat, A., & Karovic, V. (2020). Using a Two-Stage DEA Model to Measure Tourism Potentials of EU Countries and Western Balkan Countries: An Approach to Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 12(12), 4903. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124903