Could MOOC-Takers’ Behavior Discuss the Meaning of Success-Dropout Rate? Players, Auditors, and Spectators in a Geographical Analysis Course about Natural Risks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Research

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sample Data

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographics

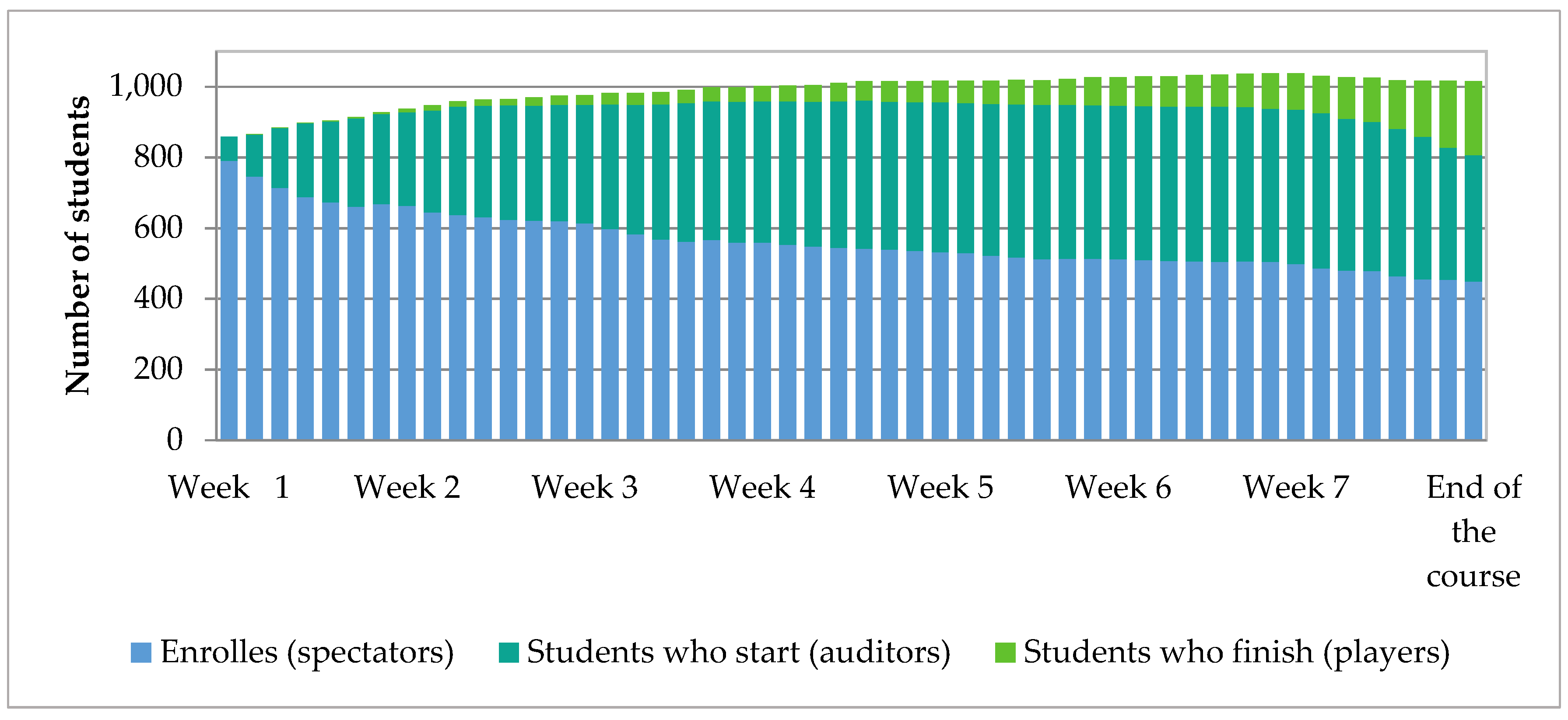

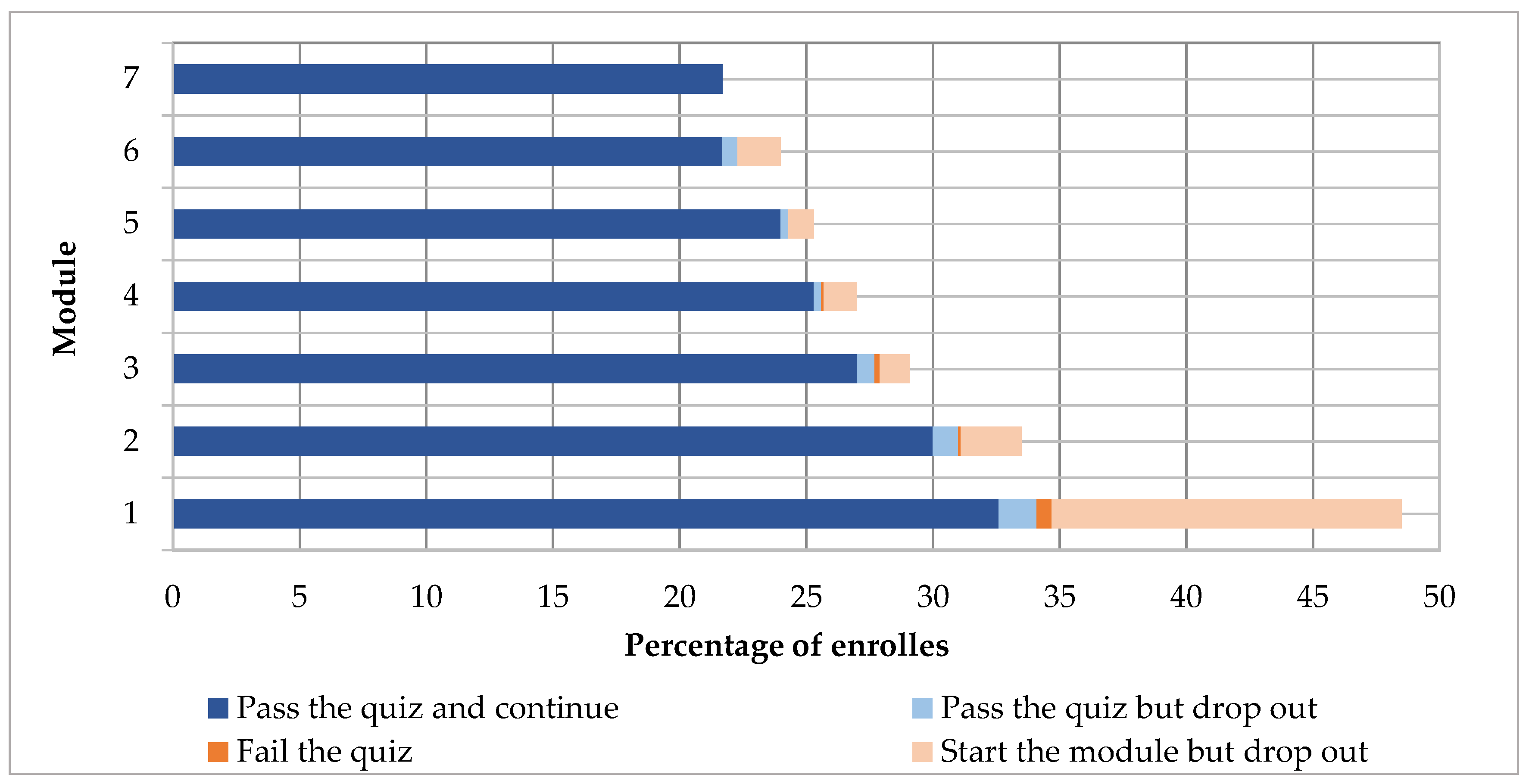

4.2. Success-Dropout Rates

4.3. Engagement, Achievement, and Scoring

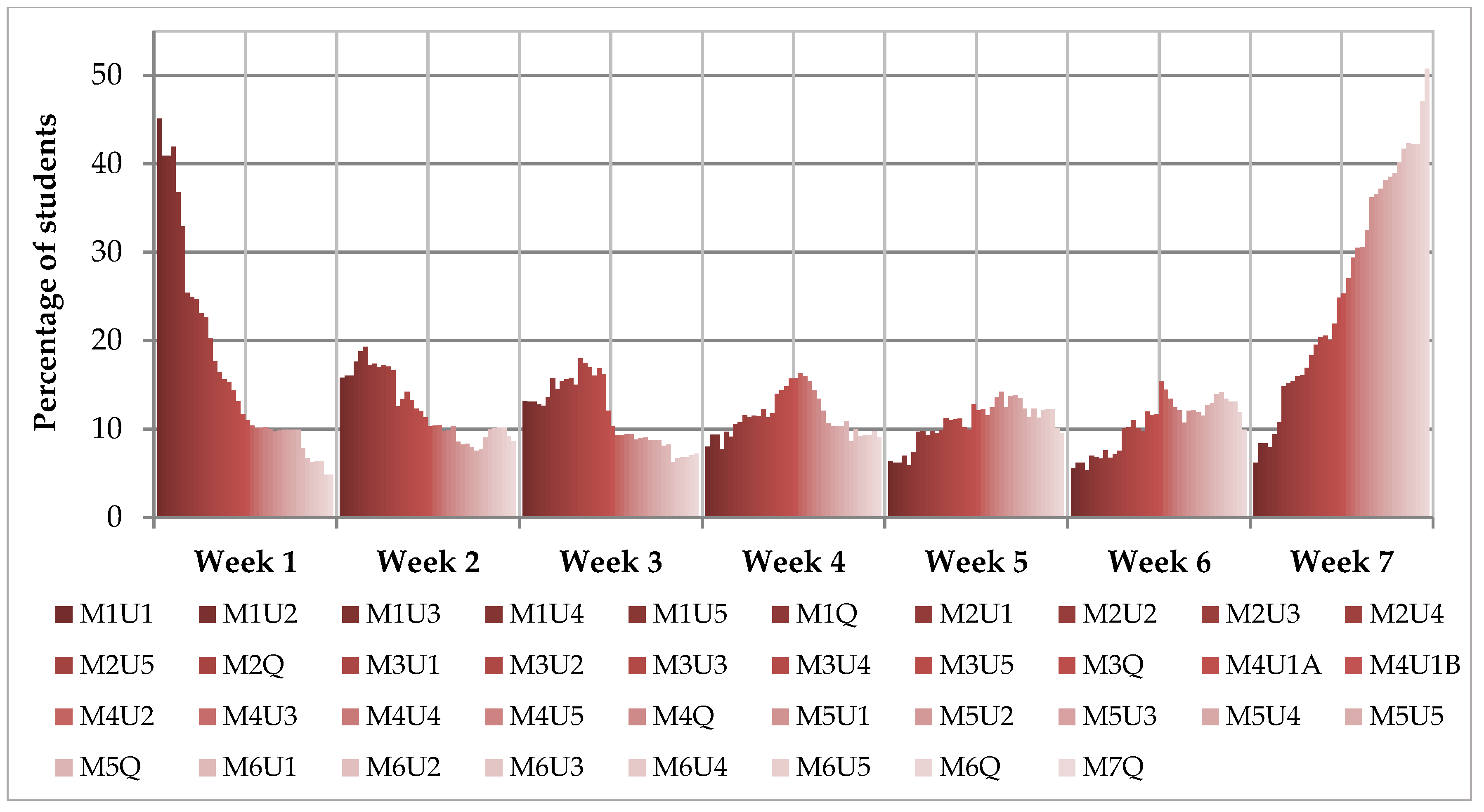

4.3.1. Engagement Periods

4.3.2. Achievement by Unit Interest and Time Length

4.3.3. Module Quizzes Score

4.4. Behaviour

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- Students who obtain partial learning (auditors or learners) take longer to complete the modules and obtain worse grades. To address this gap, it should be useful to send questionnaires to those who do not finish the course, asking why (lack of interest in the course content, does not meet expectations, need for specific knowledge already satisfied, lack of time, the difficulty of the course, etc.).

- Students who complete tasks during the weekend take less time to complete the modules and obtain a better grade. This could be related to many factors, but it would be interesting to focus the communication strategies with the students to be promoted also during the weekend (beyond reminders or communication at the beginning of the modules that are provided each Monday).

- Students who start earlier and those who finish earlier obtain better grades in some of the modules (motivation could be the explanation, but also students’ background in the subject: Natural risks). However, ‘last moment students’ (those students who complete the course last week) demonstrated that speed in passing the modules is either related to greater motivation, although in this case it is not related to better grades.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baggaley, J. Online learning: A new testament. Distance Educ. 2014, 35, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witthaus, G.; Inamorato dos Santos, A.; Childs, M.; Tannhäuser, A.; Conole, G.; Nkuyubwatsi, B.; Punie, Y. Validation of non-formal MOOC-based learning: An analysis of assessment and recognition practices in Europe (OpenCred). EUR 27660 EN 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moural, V.F.; Souzal, C.A.; Oliveira-Neto, J.D.; Viana, A.B.N. MOOC’s potential for democratizing education: An analysis from the perspective of access to technology. In EMCIS 2017; Themistocleous, M., Morabito, V., Eds.; University of Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2017; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.; Herbert, J.; Teras, M. A sense of belonging to enhance participation, success and retention in online programs. Int. J. First Year High. Educ. 2014, 5, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoletti, R. Learning through design: MOOC development as a method for exploring teaching methods. Curr. Issues Emerg. e-Learn. 2016, 3, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Poël, J.F.; Verpoorten, D. Designing a MOOC—A new channel for teacher professional development. In Digital Education: At the MOOC Crossroads Where the Interests of Academia and Business Converge; Calise, M., Delgado-Kloos, C., Reich, J., Ruiperez-Valiente, J., Wirsing, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Margaryan, A.; Bianco, M.; Littlejohn, A. Instructional quality of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, E.; Chang, Y.; Park, S. Design review of MOOCs: Application of e-learning design principles. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, R.P.; Milligan, C.; Littlejohn, A.; Margaryan, A. Measuring self-regulated learning in the workplace. Int. J. Train. Dev. 2015, 19, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño-Muñoz, J.; Kalz, M.; Kreijns, K.; Punie, Y. Who is taking MOOCs for teachers’ professional development on the use of ICT? A cross-sectional study from Spain. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 2018, 27, 607–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, N.; Littlejohn, A.; Milligan, C. Context counts: How learners’ contexts influence learning in a MOOC. Comput. Educ. 2015, 91, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chick, R.C.; Clifton, G.T.; Peace, K.M.; Propper, B.W.; Hale, D.F.; Alseidi, A.A.; Vreeland, T.J. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Surg. Educ. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Chinese university students’ acceptance of MOOCs: A self-determination perspective. Comput. Educ. 2016, 92–93, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diver, P.; Martinez, I. MOOCs as a massive research laboratory: Opportunities and challenges. Distance Educ. 2015, 36, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Fraihat, D.; Joy, M.; Masa’deh, R.; Sinclair, J. Evaluating e-learning systems success: An empirical study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 102, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderikx, M.; Kreijns, K.; Kalz, M. A classification of barriers that influence intention achievement in MOOCs. In Lifelong Technology-Enhanced Learning. Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; Pammer-Schindler, V., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., Drachsler, H., Elferink, R., Scheffel, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Henderikx, M.A.; Kreijns, K.; Kalz, M. Refining success and dropout in massive open online courses based on the intention-behavior gap. Distance Educ. 2017, 38, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J.A.; Oswald, C.A.; Pomerantz, J. Predictors of retention and achievement in a massive open online course. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2015, 52, 925–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Higher education and the digital revolution: About MOOCs, SPOCs, social media, and the Cookie Monster. Bus. Horiz. 2016, 59, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Alamri, M.M.; Alyoussef, I.Y.; Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Kamin, Y.B. Integrating innovation diffusion theory with technology acceptance model: Supporting students’ attitude towards using a massive open online courses (MOOCs) systems. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2019. Latest articles. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, L.W.; Ruby, A.; Boruch, R.F.; Wang, N.; Scull, J.; Ahmad, S.; Evans, C. Moving through MOOCs: Understanding the progression of users in Massive Open Online Courses. Educ. Res. 2014, 43, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, L.; Pritchard, D.E.; de Boer, J.; Stump, G.S.; Ho, A.D.; Seaton, D.T. Studying learning in the worldwide classroom: Research into EdX’s first MOOC. Res. Pract. Assess. 2013, 8, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, L.; Chunrao, D. Influencing factors of success and failure in MOOC and general analysis of learner behavior. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2016, 6, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K. Massive open online course completion rates revisited: Assessment, length and attrition. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2015, 16, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barba, P.G.; Kennedy, G.E.; Ainley, M.D. The role of students’ motivation and participation in predicting performance in a MOOC. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2016, 32, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraimi, K.M.; Zo, H.; Ciganek, A.P. Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of openness and reputation. Comput. Educ. 2015, 80, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu-Agyeman, Y.; Larbi-Shaw, O. Exploring the factors that enhance student–content interaction in a technology-mediated learning environment. Cogent Educ. 2018, 5, 1456780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravani, M.N. Adult learning in a distance education context: Theoretical and methodological challenges. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2014, 34, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, J. Digital culture clash: “Massive” education in the E-learning and Digital Cultures MOOC. Distance Educ. 2014, 35, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doo, M.Y.; Tang, Y.; Bonk, C.J.; Zhu, M. MOOC instructor motivation and career development. Distance Educ. 2020, 41, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, J.; Ramírez-Hernández, D. Innovative education in MOOC for sustainability: Learnings and motivations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaton, D.T.; Bergner, Y.; Chuang, I.; Mitros, P.; Pritchard, D.E. Who does what in a massive open online course? Commun. ACM 2014, 57, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Hew, K.F. Examining learning engagement in MOOCs: A self-determination theoretical perspective using mixed method. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2020, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hew, K.F. Promoting engagement in online courses: What strategies can we learn from three highly rated MOOCS? Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 47, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R. Framing student engagement in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Kang, J.; McKelroy, E. Examining learners’ perspective of taking a MOOC: Reasons, excitement, and perception of usefulness. Educ. Media Int. 2015, 52, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, M.; Hadi, S.M. Supporting, categorizing and visualising diverse learner behaviour on MOOCs with modular design and micro-learning. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2017, 29, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hew, K.F.; Cheung, W.S. Students’ and instructors’ use of massive open online courses (MOOCs): Motivations and challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 12, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mönter, L.; Otto, K.-H. The concept of disasters in Geography Education. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2018, 42, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Chang, Y.-L.; Shiau, J.S.; Wang, S.M. Exploring the effects of a serious game-based learning package for disaster prevention education: The case of the Battle of Flooding Protection. Reduction 2020, 43, 101393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Gurtner, Y.; Firdaus, A.; Harwood, S.; Cottrell, A. Land use planning for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. Operationalizing policy and legislation at local levels. Int. J. Disaster Res. Built Environ. 2016, 7, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echavarren, J.M.; Balzekiene, A.; Telesiene, A. Multilevel analysis of climate change risk perception in Europe: Natural hazards, political contexts and mediating individual effects. Saf. Sci. 2019, 120, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhruddin, B.; Boylan, K.; Wild, A.; Robertson, R. Chapter 12-Assessing vulnerability and risk of climate change. In Climate Extremes and Their Implications for Impact and Risk Assessment; Sillmann, J., Sippel, S., Russo, S., Eds.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2020; pp. 217–241. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, J.D.; Hannah, D.M.; Liu, W. Editorial: Citizen Science: Reducing risk and building resilience to natural hazards. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Clark, A.L. A modern risk society and resilience-based public policy: Structural views. In Nexus of Resilience and Public Policy in a Modern Risk Society; Shimizu, M., Clark, A.L., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, A.; Arvai, J. Perceptions of risk and vulnerability following exposure to a major natural disaster: The Calgary flood of 2013. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Barba, P.G.; Malekian, D.; Oliveira, E.A.; Bailey, J.; Ryan, T.; Kennedy, G. The importance and meaning of session behaviour in a MOOC. Comput. Educ. 2020, 146, 103772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, R.M.; Borokhovski, E.; Schmid, R.F.; Tamim, R.M.; Abrami, P.C. A meta-analysis of blended learning and technology use in higher education: From the general to the applied. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2014, 33, 87–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Benckendorff, P.; Gannaway, D. Progress and new directions for teaching and learning in MOOCs. Comput. Educ. 2019, 129, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, A.; Corrin, L.; de Barba, P.; Lodge, J.; Kennedy, G. A tale of two MOOCs: How student motivation and participation predict learning outcomes in different MOOCs. Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Palmero, J.; López-Álvarez, D.; Sánchez-Rivas, E.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, J. An analysis of the profiles and the opinion of students enrolled on xMOOCs at the University of Málaga. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Schenke, K.; Eccles, J.-S.; Xu, D.; Warschauer, M. Cross-national comparison of gender differences in the enrollment in and completion of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics Massive Open Online Courses. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, S.L.; Watson, W.R.; Yu, J.H.; Alamri, H.; Mueller, C. Learner profiles of attitudinal learning in a MOOC: An explanatory sequential mixed methods study. Comput. Educ. 2017, 114, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Beemt, A.; Buijs, J.; van der Aalst, W. Analysing structured learning behaviour in massive open online courses (MOOCs): An approach based on process mining and clustering. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2018, 19, 38–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannert, M.; Reimann, P.; Sonnenberg, C. Process mining techniques for analyzing patterns and strategies in students’ self-regulated learning. Metacognit. Learn. 2014, 9, 161–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, J.; Gasevic, D.; Dawson, S.; Pardo, A.; Mirriahi, N. Learning analytics to unveil learning strategies in a flipped classroom. Internet High. Educ. 2017, 33, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunar, A.S.; Abbasi, R.A.; Davis, H.C.; White, S.; Aljohani, N.R. Modelling MOOC learners’ social behaviours. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 107, 105835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Rienties, B.; Rogaten, J.; Kizilcec, R.F. Investigating variation in learning processes in a FutureLearn MOOC. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 162–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruthotto, I.; Kreth, Q.; Stevens, J.; Trively, C.; Melkers, J. Lurking and participation in the virtual classroom: The effects of gender, race, and age among graduate students in computer science. Comput. Educ. 2020, 151, 103854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walji, S.; Deacon, A.; Small, J.; Czerniewicz, L. Learning through engagement: MOOCs as an emergent form of provision. Distance Educ. 2016, 37, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.A.; Merzdorf, H.E.; Hicks, N.M.; Sarfraz, M.I.; Bermel, P. Challenges to assessing motivation in MOOC learners: An application of an argument-based approach. Comput. Educ. 2020, 150, 103829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Khalil, M.; Baars, M.; de Koning, B.B.; Paas, F. Exploring sequences of learner activities in relation to self-regulated learning in a massive open online course. Comput. Educ. 2019, 140, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, E.; Gronseth, S.L.; McNeil, S.G.; Bonk, C.J.; Robin, B.R. Goal setting and MOOC completion: A study on the role of self-regulated learning in student performance in Massive Open Online Courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2019, 20, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Kim, M.K.; Xiong, Y. Individual learning vs. interactive learning: A cognitive diagnostic analysis of MOOC students’ learning behaviors. Am. J. Distance Educ. 2020. Latest articles. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.-H.; Kim, B.J. Students’ self-regulation for interaction with others in online learning environments. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 17, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, M.D. First principles of instruction. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2002, 50, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Loro, F.; Martin, S.; Ruipérez-Valiente, J.A.; Sancristobal, E.; Castro, M. Reviewing and analyzing peer review Inter-Rater Reliability in a MOOC platform. Comput. Educ. 2020, 154, 103894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivé, D.M.; Huynh, D.Q.; Reynolds, M.; Dougiamas, M.; Wiese, D. A supervised learning framework: Using assessment to identify students at risk of dropping out of a MOOC. J. Comput. High. Educ. 2020, 32, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poellhuber, B.; Roy, N.; Bouchoucha, I. Understanding participant’s behaviour in massively open online courses. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 2019, 20, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.C.; Kerski, J.; Long, E.C.; Luo, H.; DiBiase, D.; Lee, A. Maps and the geospatial revolution: Teaching a massive open online course (MOOC) in geography. J. Geog. High. Educ. 2015, 39, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizutori, M. Reflections on the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction: Five years since its adaptation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Content |

|---|---|

| Title of the course | Geographical analysis of natural risk: Perceive, plan, and manage |

| E-learning platform and social network profile | MiriadaX (www.miriadax.net); @MoocRiesgosUA |

| Institution | University of Alicante, Spain |

| Organization and production | Interuniversity Institute of Geography and Faculty of Arts |

| Date (1st edition) | 9 September–27 October 2019 |

| Length | 7 weeks |

| Structure | 6 content modules (6 quizzes, 30 thematic units in total) + presentation module + evaluation module (final quiz) |

| Estimated workload | 4–5 h per week (30 h in total) |

| Scientific area | Geography (Social Sciences), Environmental Sciences |

| Level | Introductory |

| Prerequisites | None |

| Teachers | 10 (2–3 for module) |

| Language of exposition, video subtitles and transcriptions | Spanish |

| Supplementary material | Spanish, English |

| Assessment | Module quizzes and forum discussions |

| Learners’ Groups | Module 1 | Module 2 | Module 3 | Module 4 | Module 5 | Module 6 | Module 7 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | N | SA | SSD | TA | TSD | ||

| COURSE | 346 | 77.3 | 16 | 5.1 | 8.4 | 306 | 79.4 | 15.9 | 2.6 | 5.1 | 281 | 76.1 | 16.4 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 260 | 77.1 | 16.8 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 247 | 81.9 | 15.8 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 226 | 82.2 | 17.4 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 221 | 80.8 | 15.4 | 23.3 | 15.9 | |

| GENDER | Men | 215 | 78 | 15.1 | 4.6 | 7.6 | 194 | 79.4 | 15.4 | 2.3 | 4.8 | 181 | 76.3 | 16.1 | 2.3 | 4.5 | 172 | 77.3 | 16.2 | 2.9 | 5 | 163 | 81.5 | 15.8 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 148 | 82.9 | 17.2 | 1.5 | 4.2 | 145 | 81 | 14.3 | 21.8 | 15.8 |

| Women | 120 | 76.1 | 16.8 | 5.9 | 9.4 | 104 | 79.5 | 16.5 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 95 | 75.4 | 16.5 | 2.2 | 4 | 84 | 76.4 | 17.7 | 2.7 | 6 | 80 | 82 | 16 | 0.9 | 1.8 | 76 | 81.3 | 17.7 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 74 | 80.2 | 17.4 | 25.8 | 16.1 | |

| TYPE OF LEARNING | Total | 221 | 77.8 | 15.7 | 4.8 | 7.9 | 221 | 80.4 | 16.0 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 221 | 77.1 | 16.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 221 | 77.8 | 16.3 | 2.9 | 5.5 | 221 | 81.9 | 15.9 | 1.1 | 2.7 | 221 | 82.0 | 17.6 | 1.4 | 3.7 | 221 | 80.8 | 15.4 | 23.3 | 15.9 |

| Partial | 125 | 76.5 | 16.5 | 5.8 | 9.4 | 85 | 77.1 | 15.3 | 3.0 | 5.0 | 60 | 72.5 | 17.3 | 3.4 | 6.0 | 39 | 72.3 | 19.5 | 2.7 | 4.0 | 26 | 81.2 | 15.6 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 6 | 88.3 | 11.7 | 1.8 | 3.6 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| WEEKDAY | Midweek | 268 | 77.4 | 15.8 | 4.7 | 7.8 | 222 | 78.2 | 15.9 | 2.9 | 5.4 | 206 | 75.8 | 15.8 | 2.6 | 4.9 | 174 | 76.8 | 16.9 | 3.1 | 5.5 | 151 | 82.1 | 15.3 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 137 | 80.7 | 17.7 | 1.8 | 4.3 | 121 | 80.0 | 14.8 | 21.6 | 14.3 |

| Weekend | 78 | 77.3 | 16.7 | 6.7 | 10.3 | 84 | 82.6 | 15.4 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 75 | 77.2 | 17.9 | 1.6 | 3.0 | 86 | 77.7 | 16.5 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 96 | 81.5 | 16.7 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 89 | 84.6 | 16.9 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 100 | 81.7 | 16.1 | 25.4 | 17.5 | |

| STARTING PERIOD | 1st week | 114 | 80.0 | 15.5 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 105 | 81.9 | 15.8 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 99 | 76.6 | 16.9 | 2.4 | 5.0 | 89 | 79.4 | 15.3 | 3.3 | 6.8 | 87 | 83.2 | 16.1 | 1.4 | 3.6 | 78 | 83.5 | 16.9 | 2.3 | 5.3 | 76 | 82.7 | 13.5 | 25.1 | 16.6 |

| >First week | 232 | 76.0 | 16.1 | 7.0 | 9.7 | 201 | 78.2 | 15.8 | 2.8 | 5.4 | 182 | 75.9 | 16.1 | 2.2 | 4.2 | 171 | 75.8 | 17.4 | 2.6 | 4.3 | 160 | 81.1 | 15.7 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 148 | 81.6 | 17.8 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 145 | 79.8 | 16.3 | 22.3 | 15.5 | |

| ENDING PERIOD | <Last week | 109 | 77.7 | 16.6 | 2.6 | 5.0 | 109 | 81.7 | 16.1 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 109 | 78.0 | 16.0 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 109 | 80.6 | 15.3 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 109 | 83.8 | 15.7 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 109 | 82.2 | 17.6 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 109 | 82.6 | 14.8 | 15.7 | 12.4 |

| Last week | 112 | 77.9 | 14.9 | 6.9 | 9.5 | 112 | 79.0 | 15.8 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 112 | 76.3 | 16.0 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 112 | 75.1 | 16.8 | 4.2 | 7.0 | 112 | 80.2 | 15.9 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 112 | 81.9 | 17.7 | 1.8 | 4.6 | 112 | 79.1 | 15.6 | 30.7 | 15.5 | |

| LAST MOMENT | ≥ 4 modules | 151 | 77.5 | 15.5 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 151 | 80.9 | 15.6 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 151 | 77.7 | 15.4 | 1.9 | 3.6 | 151 | 77.4 | 15.9 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 151 | 82.6 | 15.7 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 151 | 81.7 | 17.4 | 1.9 | 4.4 | 151 | 81.4 | 15.4 | 22.1 | 15.5 |

| Rest | 70 | 78.6 | 16.2 | 7.6 | 11.2 | 70 | 79.3 | 16.9 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 70 | 76.0 | 17.2 | 2.2 | 4.7 | 70 | 78.6 | 17.1 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 70 | 80.6 | 16.4 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 70 | 82.7 | 18.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 70 | 79.6 | 15.4 | 25.8 | 16.7 | |

| M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | Average Time | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | W = 67,234 p-value = 1 × 10−8 | W = 60,912 p-value = 4 × 10−7 | W = 53,138, p-value = 0.0005 | W = 59,663, p-value = 2 × 10−15 | W = 53,674 p-value = 1 × 10−12 | 5.1 |

| M2 | - | W = 41,300 p-value = 0.36 | W = 35,560 p-value = 0.02 | W = 41,614 p-value = 0.04 | W = 37,023 p-value = 0.19 | 2.62 |

| M3 | - | - | W = 33,829 p-value = 0.10 | W = 40,031 p-value = 0.003 | W=35,859 p-value= 0.01 | 2.27 |

| M4 | - | - | - | W = 39,578 p-value = 8 × 10−6 | W = 35,668 p-value = 0.0001 | 2.82 |

| M5 | - | - | - | - | W = 27,281 p-value = 0.61 | 1.15 |

| M6 | - | - | - | - | - | 1.43 |

| M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | Average Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | W = 49,445 p-value = 0.10 | W = 51,028 p-value = 0.34 | W = 45,739 p-value = 0.82 | W = 35,929 p-value = 0.0004 | W = 32,241 p-value = 0.0001 | W = 32,558 p-value = 0.001 | 77.3 |

| M2 | - | W = 48,113 p-value = 0.01 | W = 43,286 p-value = 0.09 | W = 34,618 p-value = 0.06 | W = 30,896 p-value = 0.02 | W = 31,408 p-value = 0.1206 | 79.4 |

| M3 | - | - | W = 35,729 p-value = 0.55 | W = 27,963 p-value = 5 × 10−5 | W=25,278 p-value = 3 × 10−5 | W = 25,357 p-value= 0.0002 | 76.1 |

| M4 | - | - | - | W = 27,074 p-value = 0.001 | W = 24,351 p-value = 0.0005 | W = 24,696 p-value=0.004 | 77.1 |

| M5 | - | - | - | - | W=27,131 p-value=0.48 | W = 27,881 p-value = 0.80 | 81.9 |

| M6 | - | - | - | - | - | W = 26,482 p-value = 0.34 | 82.2 |

| M7 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 80.8 |

| Learners’ Groups | M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | Quiz score | 0.24 | 0.91 | 0.53 | 0.71 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 0.99 |

| Time length | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.9 | 0.52 | 0.99 | 0.76 | 0.08 * | |

| TYPE OF LEARNING | Quiz score | 0.45 | 0.08 * | 0.05 * | 0.12 | 0.74 | 0.51 | - |

| Time length | 0.79 | 0.09 * | 0.29 | 0.64 | 0.32 | 0.65 | - | |

| WEEKDAY | Quiz score | 0.93 | 0.03 ** | 0.47 | 0.7 | 0.92 | 0.07* | 0.3 |

| Time length | 0.42 | 0.09 * | 0.02 ** | 0.03 ** | 0.02 ** | <0.01 *** | 0.06 * | |

| BEGINNING PERIOD | Quiz score | 0.02 ** | 0.04 ** | 0.89 | 0.11 | 0.26 | 0.5 | 0.27 |

| Time length | <0.01 *** | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.5 | 0.39 | <0.01 *** | 0.16 | |

| ENDING PERIOD | Quiz score | 0.97 | 0.18 | 0.45 | 0.01 ** | 0.07 * | 0.9 | 0.09 * |

| Time length | <0.01 *** | <0.01 *** | 0.05 * | <0.01 *** | 0.1 | 0.44 | <0.01 *** | |

| LAST MOMENT | Quiz score | 0.64 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.39 |

| Time length | 0.06 * | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 0.17 | <0.01 *** | 0.09 * | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ricart, S.; Villar-Navascués, R.A.; Gil-Guirado, S.; Hernández-Hernández, M.; Rico-Amorós, A.M.; Olcina-Cantos, J. Could MOOC-Takers’ Behavior Discuss the Meaning of Success-Dropout Rate? Players, Auditors, and Spectators in a Geographical Analysis Course about Natural Risks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124878

Ricart S, Villar-Navascués RA, Gil-Guirado S, Hernández-Hernández M, Rico-Amorós AM, Olcina-Cantos J. Could MOOC-Takers’ Behavior Discuss the Meaning of Success-Dropout Rate? Players, Auditors, and Spectators in a Geographical Analysis Course about Natural Risks. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124878

Chicago/Turabian StyleRicart, Sandra, Rubén A. Villar-Navascués, Salvador Gil-Guirado, María Hernández-Hernández, Antonio M. Rico-Amorós, and Jorge Olcina-Cantos. 2020. "Could MOOC-Takers’ Behavior Discuss the Meaning of Success-Dropout Rate? Players, Auditors, and Spectators in a Geographical Analysis Course about Natural Risks" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124878

APA StyleRicart, S., Villar-Navascués, R. A., Gil-Guirado, S., Hernández-Hernández, M., Rico-Amorós, A. M., & Olcina-Cantos, J. (2020). Could MOOC-Takers’ Behavior Discuss the Meaning of Success-Dropout Rate? Players, Auditors, and Spectators in a Geographical Analysis Course about Natural Risks. Sustainability, 12(12), 4878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124878