Capturing Transgressive Learning in Communities Spiraling towards Sustainability

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The act of transgressing; the violation of a law or a duty or moral principle

- The action of going beyond or overstepping some boundary or limit

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Theory of Transgressive Learning

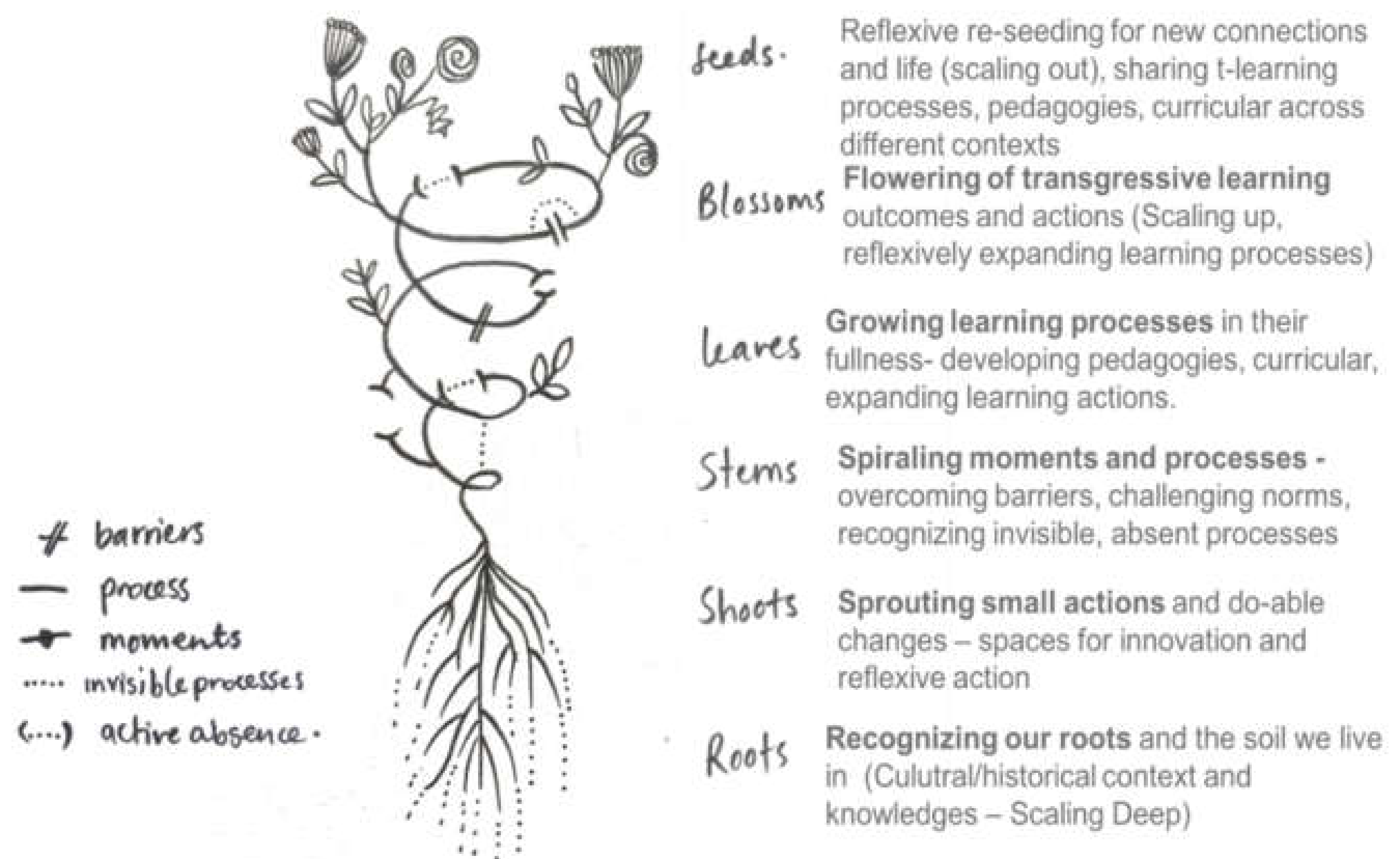

2.2. The Living Spiral Model

3. Methodological Framework

3.1. Transformation Labs (T-Labs)

3.2. Critical Event Inquiry

3.3. Thematic Analysis

4. Data Analysis: Results

4.1. Roots

4.2. Shoots

4.3. Stems

4.3.1. Barriers

4.3.2. (Invisible) Processes

4.3.3. Active/Passive Absence

4.4. Leaves

4.5. Blossoms

4.6. Seeds

5. Discussion

5.1. Addressing Uncertainty by Taking a Step Back and Reflecting

5.2. Community and Relationality Driving Deeper Questions of Purpose and Belonging

5.3. Unveiling ’Absences’ through Transgressive Learning

5.4. Research Limitations

5.5. Key Conclusions and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- “What have been three to five (3–5) events or experiences that have been most significant during the process of the T-Lab you have been part of?” (Original in Spanish: ¿Cuáles han sido los tres a cinco (3–5) eventos o experiencias que han sido más significativas en el proceso del T-lab del que hace parte?)

- “If we define transformative learning as a change in reference points, and world-visions, to what extent have these experiences been transformative to you and your community?” [to interviewer: If yes, why; if no, why not? What was the transformation and why did it happen?] (Original in Spanish: Si definimos el aprendizaje transformativo como un cambio en los puntos de referencia y visiones del mundo, ¿Hasta que punto han sido estos eventos transformativos para usted, para el grupo? ¿Por que si o por que no? (¿cuál fue la transformación? Y porque la transformación sucedió?).

- To interviewer: If the answers to questions 1 and 2 only reference personal changes, ask the following question. “Was there an event or experience that was transformative for the group or the collective?” (original in Spanish: Si las respuestas de la pregunta 1 y 2 hacen referencia solo a cambios personales/individuales hacer la pregunta: ¿Hay algún evento o experiencia que hayasido transformativa para el grupo como colectivo?

- How would you relate these experiences with the challenges of climate change (food sovereignty/security and water, water, social justice, energy) at the personal and community level? (Original in Spanish: ¿Cómo se relacionan estas experiencias con los retos de abordar el cambio climático (soberanía/seguridad alimentaria y de agua, justicia social, energía) en los niveles personal, en tu comunidad?

References

- Transgression Transgression. Available online: https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/transgression (accessed on 1 March 2019).

- Markowitz, E.M.; Shariff, A.F. Climate change and moral judgement. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2012, 2, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettenger, M.E. The Social Construction of Climate Change: Power, Knowledge, Norms, Discourses; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781317015857. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Climate Change. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/climate-change/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Wahl, D. Designing Regenerative Cultures; Triarchy Press: Axminister, UK, 2016; ISBN 9781909470781. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, J.B. Transgressive, but Fun!: Music in University Learning Environments, Higher Education Practices Series; Aalborg Universitetsforlag: Aalborg, Denmark, 2016; Volume 3, ISBN 24461881. [Google Scholar]

- Mookerjee, R. Transgressive Fiction: The New Satiric Tradition; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781137341082. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, N.J. Practice-based Evidence: Towards Collaborative and Transgressive Research. Sociology 2003, 37, 81–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Peters, M. Flowers of resistance. Citizen science, ecological democracy and the transgressive education paradigm. In Sustainability Science; König, A., Ed.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D. Transgressing planetary boundaries. Sci. Am. 2009, 301, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.M.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Sustainability. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015, 347, 1259855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Stuart Chapin, F., III; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E.J. Learning in a changing world and changing in a learning world: Reflexively fumbling towards sustainability. South. Afr. J. Environ. Educ. 2007, 24, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- IPPC. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. In Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, J.K., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., White, L.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Wals, A.E.J.; Kronlid, D.; McGarry, D. Transformative, transgressive social learning: Rethinking higher education pedagogy in times of systemic global dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Ali, M.B.; Mphepo, G.; Chaves, M.; Macintyre, T.; Pesanayi, T.; Wals, A.E.J.; Mukute, M.; Kronlid, D.; Tran, D.T.; et al. Co-designing research on transgressive learning in times of climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 20, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, T.; Chaves, M.; McGarry, D. Marco Conceptual del Espiral Vivo / Living Spiral Framework; Project T-Learning: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, T.; Monroy, T.; Coral, D.; Zethelius, M.; Tassone, V.; Wals, A.E.J. T-labs and climate change narratives: Co-researcher qualities in transgressive action–research. Action Res. 2019, 17, 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, T. The Transgressive Gardener: Cultivating Learning-Based Transformations towards Regenerative Futures. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University and Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 18 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mezirow, J. Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997, 1997, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabove, V. The Many Facets of Transformative Learning Theory and Practice. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 1997, 1997, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.W. An update of transformative learning theory: A critical review of the empirical research (1999–2005). Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2007, 26, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M. Calling Transformative Learning into Question: Some Mutinous Thoughts. Adult Educ. Q. 2012, 62, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, S. Sustainable Education: Re-Visioning Learning and Change, Schumacher Briefings; Green Books for the Schumacher Society: Bristol, UK, 2001; ISBN 9781870098991. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. Learning for an unknown future. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 2004, 23, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassone, V.C.; O’Mahony, C.; McKenna, E.; Eppink, H.J.; Wals, A.E.J. (Re-)designing higher education curricula in times of systemic dysfunction: A responsible research and innovation perspective. High Educ. 2017, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ojala, M. Facing anxiety in climate change education: From therapeutic practice to hopeful transgressive learning. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 21, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, A. Sustainability: Design for the pluriverse. Development 2011, 54, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A. Ontological politics. A word and some questions. Sociol. Rev. 1999, 47, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.; Macintyre, T.; Verschoor, G.; Wals, A.E.J. Towards Transgressive Learning through Ontological Politics: Answering the “Call of the Mountain” in a Colombian Network of Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Macintyre, T.; Chaves, M. Balancing the Warrior and Empathic Activist: The role of the Transgressive Researcher in Environmental Education. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 2017, 22, 80–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hooks, B. Teaching To Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994; ISBN 9781135200015. [Google Scholar]

- Layne, P.C.; Lake, P. Global Innovation of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Transgressing Boundaries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; ISBN 9783319104829. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, M. Transgressive pedagogies? Exploring the difficult realities of enacting feminist pedagogies in undergraduate classrooms in a Canadian university. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarnivaara, M.; Ellis, C.; Kinnunen, H.-M. Transgressive Learning: A Possible Vista in Higher Education. In Transitions and Transformations in Learning and Education; Tynjälä, P., Stenström, M.-L., Saarnivaara, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 307–325. ISBN 9789400723122. [Google Scholar]

- Concepción, D.W.; Eflin, J.T. Enabling Change: Transformative and Transgressive Learning in Feminist Ethics and Epistemology. Teach. Philos. 2009, 32, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, T.; Chaves, M.; Monroy, T.; Zethelius, M.O.; Villarreal, T.; Tassone, V.C.; Wals, A.E.J. Transgressing Boundaries between Community Learning and Higher Education: Levers and Barriers. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodney, R. Decolonization in health professions education: Reflections on teaching through a transgressive pedagogy. Can. Med. Educ. J. 2016, 7, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Macintyre, T. What do we mean by T-learning? Definitions and acts of defining. Project T-Learning. Available online: http://transgressivelearning.org/2017/09/06/mean-t-learning-definitions-acts-defining/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Lotz-Sisitka, H.; Mukute, M.; Chikunda, C.; Baloi, A.; Pesanayi, T. Transgressing the norm: Transformative agency in community-based learning for sustainability in southern African contexts. Int. Rev. Educ. 2017, 63, 897–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M.; Wals, A.E.J. The Nature of Transformative Learning for Social-ecological Sustainability. In Grassroots to Global: Broader Impacts of Civic Ecology; Krasny, M.E., Tidball, K.G., Maddox, D., Eds.; Cornell University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Retolaza Eguren, I. Theory of change: A thinking and action approach to navigate in the complexity of social change processes. In Democratic Dialogue Regional Project, the Regional Centre for Latin America and the Caribbean, UNDP and Humanistic Institute for Development Cooperation (HIVOS); Hivos: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey, A.; Mackenzie, M. Theories of Change and Realistic Evaluation: Peas in a Pod or Apples and Oranges? Evaluation 2007, 13, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J.; associates (Eds.) Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress; The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education Series; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 9780787948450. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Ontologies, socio-technical transitions (to sustainability), and the multi-level perspective. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A. Development Practitioners and Social Process Artists of the Invisible; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry, D. Empathy in the Time of Ecological Apartheid: A Social Sculpture Practice-Led Inquiry Into Developing Pedagogies for Ecological Citizenship. Ph.D. Thesis, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Engeström, Y. Studies in Expansive Learning: Learning What Is Not Yet There; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell, A.J. Measuring What Matters?: Exploring the Use of Values-Based Indicators in Assessing Education for Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 28 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pathways Network. T-Labs: A Practical Guide—Using Transformation Labs (T-Labs) for Innovation in Social-Ecological Systems; STEPS Centre: Brighton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, T. Mapping transgressive learning interactions in a Colombian network of sustainability initiatives. Trangressive Learning, 3 November 2017. Available online: http://transgressivelearning.org/2017/11/03/mapping-transgressive-learning-interactions-colombian-network-sustainability-initiatives/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Weisbord, M.R.; Weisbord, M.; Janoff, S. Future Search: An Action Guide to Finding Common Ground in Organizations and Communities; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000; ISBN 9781576759165. [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre, T. Answering the “Call of the Mountain” through a Spiralling Network of Sustainability. 2018, pp. 10–13. Available online: https://www.ic.org/answering-the-call-of-the-mountain-through-a-spiralling-network-of-sustainability/ (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Monroy, T. Reporte Bioregion Center. TLab III. Reconstruccion Del Cusmuy; Project T-Learning: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Monroy, T. Bioregion Centro. T-Lab 2. Diálogos Municipales Para La Paz; Project T-Learning: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zethelius, M. Reporte Bioregion Caribe.TLab I; Project T-Learning: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zethelius, M. Reporte Bioregion Caribe.T-Lab 2; Project T-Learning: Grahamstown, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Temmink, C. Building a transformative community by slowing down and “scaling deep”.Transgressive Learning, 6 April 2018. Available online: http://transgressivelearning.org/2018/04/06/building-transformative-community-slowing-scaling-deep/ (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Why Practice Holacracy? Available online: https://www.holacracy.org/explore/why-practice-holacracy (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Introduction to Timebank. Available online: https://timebank.cc/about/introduction/ (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Coffey, A.; Atkinson, P. Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, L.; Mertova, P. Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method: An Introduction to Using Critical Event Narrative Analysis in Research on Learning and Teaching; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wolgemuth, J.R.; Donohue, R. Toward an Inquiry of Discomfort: Guiding Transformation in “Emancipatory” Narrative Research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 1012–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C. Grabbing Hold of a Moving Target: Identifying and Measuring the Transformative Learning Process. J. Transform. Educ. 2008, 6, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A.E.J.; Alblas, A.H. School-based Research and Development of Environmental Education: A case study. Environ. Educ. Res. 1997, 3, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; ISBN 9780761909613. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, A.; Harder, M.K.; Mehlmann, M.; Niinimaki, K.; Thoresen, V.; Vinkhuyzen, O.; Vokounova, D.; Burford, G.; Velasco, I. Measuring What Matters: Values-Based Indicators. A Methods Sourcebook. PERL Values-Based Learning Toolkit 1. 2014. Available online: http://iefworld.org/fl/PERL_toolkit1.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2019).

- Sen, R. Budgeting for the wood-wide web. New Phytol. 2000, 145, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, H. Minding the gap: The role of social learning in linking our stated desire for a more sustainable world to our everyday actions and policies. In Social Learning: Toward a More Sustainable World; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson, S. Engaging with the Beyond—Diffracting Conceptions of T-Learning. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2019, 11, 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wals, A.E.J. Social Learning Towards a Sustainable World: Principles, Perspectives, and Praxis; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 9789086860319. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz-Sisitka, H. Chapter 2 Decolonisation as future frame for environmental and sustainability education: Embracing the commons with absence and emergence. In Envisioning Futures for Environmental; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, J.H.; Woodhill, A.J.; Hemmati, M.; Verhoosel, K.S. The MSP guide: How to Design and Facilitate Multi-Stakeholder Partnerships; Centre for Development Innovation Wageningen UR: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, U. “Transformation” as a new critical orthodoxy: The strategic use of the term “Transformation” does not prevent multiple crises. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2016, 25, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J. After Method: Mess in Social Science Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa Santos, B. Epistemologies of the South: Justice Against Epistemicide; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics of Transgressive Learning |

|---|

| 1. Ethics of transgressive learning is based on a philosophy of caring which balances the warrior stance of activism with the empathic pose of vulnerability. 2. Transgressive learning, based on disrupting structural hegemonies of power, is a form of transformative learning. 3. Transgressive learning addresses wicked sustainability issues characterized by their complex, fluid, and transient nature. 4. Transgressive learning as a methodology is normative and characterized by ‘ecologies of knowledge’. 5. With their emphasis on participatory, reflective and narrative approaches, transgressive methods are performative by nature. |

| Name | Location | Description | Specific Context for Interviews 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-Lab 1: The Call of the Mountain (CotM) | Itinerant. In the year 2017: Ecovillage Anthakarana, Quindio, Colombia | An annual intercultural gathering organized by the CASA network, bringing together a diverse collection of people, communities and projects for five days of communal living, in which participants exchange experiences on sustainable living while partaking in working councils, workshops, panel discussions, dances and other artistic pursuits. | The CotM is characterised by the pedagogy “dialogo de sabers” (knowledge dialogues), whereby ontological encounters between diverse participants are facilitated so as to encourage transformative learning [31]. The 2018 context for the gathering was a future search methodology [53], brought about by a crisis in the organizational team [54]. The interview questions presented the possibility for participants to reflect on critical moments in the CotM process. |

| T-Lab 2: Ecovillage AldeaFeliz | San Francisco, Cundinamarca, Colombia | Aldeafeliz is an intentional community of 12 people, founded in 2005. T-Labs focused on connecting ancestral technologies with modern social innovation tools, for example in the form of eco-construction, generating cohesion and action around territorial water conservation. | Following an internal reorganization of the ecovillage Aldeafeliz, a focus for the T-Labs was exploring the identity of the ecovillage residents in relation to their “mestizo” heritage, as well as to their local territory. The place-based pedagogy focused on rebuilding the ceremonial house of the community called the “Cusmuy” [55], as well as building relationships between the ecovillage, local neighborhood, and the municipality [56]. The context of the interviews was characterized by the reflection on the identity of the participants, and how this was manifested (or not) through their everyday practices. |

| T-Lab 3: The Islands of Rosario | Las Islas del Rosario, Bolivar, Colombia | The T-Labs held in the Afro-Colombian community were based on networking community initiatives in the Caribbean region. This included workshops providing tools for implementing sustainable systems in local contexts, such as non-violent communication, alongside practical courses in agroecology. | Following the legal recognition of Las Islas del Rosario as a self-determining afro-Colombian region of Colombia, local efforts have been made to organize the community around addressing climate change challenges such as access to safe drinking water, and local food production. The specific context for these T-Labs was the participation of community leaders from surrounding, Caribbean communities in how to organize themselves to gain territorial rights as native communities, as well as learning sustainable practices such as eco-construction and agro-ecology [57,58]. The context for the interviews was a reflection on these new community-organizing skills, as well as sustainability practices. |

| T-Lab 4: Lekker Nassuh | The Hague, The Netherlands | A community initiative that focuses on sustainability around a local food system. T-Labs focused on reflection workshops around the organizational principles of running the initiative. | Established in 2014, the initiative Lekker Nussuh has developed into a community comprising roughly 2500 people of which 800 are registered as members and 200 fetch a weekly vegetable package, with values based on ‘fair, local, sustainable food system’ [59]. The T-Labs has involved experiments using the governance system of Holacracy [60], and integration of a community currency called Timebank [61]. The context for the interviews was a reflection on the social relations between organizers, following major changes in how the initiative has been organized and run. |

| Value Theme | Characteristic | Sources/References |

|---|---|---|

| Acknowledging uncertainty | Disrupting the status quo of what is normally understood and accepted through addressing and adapting to what we do not understand, often by acceptance and letting go | 16/41 |

| Collaboration | Forms of working together, such as through social technologies | 10/12 |

| Communication | The way we share or exchange information | 5/5 |

| Community | Being part of a group with common characteristics and valuing the greater good of that group over the individual | 14/30 |

| Diversity | Focus on multiplicity alongside inclusivity | 10/20 |

| Education | Reflection and learning | 12/21 |

| Optimism | A sense of positivity through inspiration, compassion, and appreciation | 10/17 |

| Order | Planning and design, for example, to ensure safety or to reach goals | 13/27 |

| Practice | Hands-on experiential learning, for example through experiencing novelties and local development | 13/28 |

| Relationality | An understanding of how everything is connected and related to one another, for example, typical in ancestral knowledge and spirituality. | 12/39 |

| Responsibility | Commitment and leadership | 9/15 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Macintyre, T.; Tassone, V.C.; Wals, A.E.J. Capturing Transgressive Learning in Communities Spiraling towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124873

Macintyre T, Tassone VC, Wals AEJ. Capturing Transgressive Learning in Communities Spiraling towards Sustainability. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124873

Chicago/Turabian StyleMacintyre, Thomas, Valentina C. Tassone, and Arjen E. J. Wals. 2020. "Capturing Transgressive Learning in Communities Spiraling towards Sustainability" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124873

APA StyleMacintyre, T., Tassone, V. C., & Wals, A. E. J. (2020). Capturing Transgressive Learning in Communities Spiraling towards Sustainability. Sustainability, 12(12), 4873. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124873