3. Comparison of Urban Changes in Seoul and Taipei as They Became Modern Colonial Cities 1: The Growth of Japanese Settlements and the Formation of Mixed Residential Areas

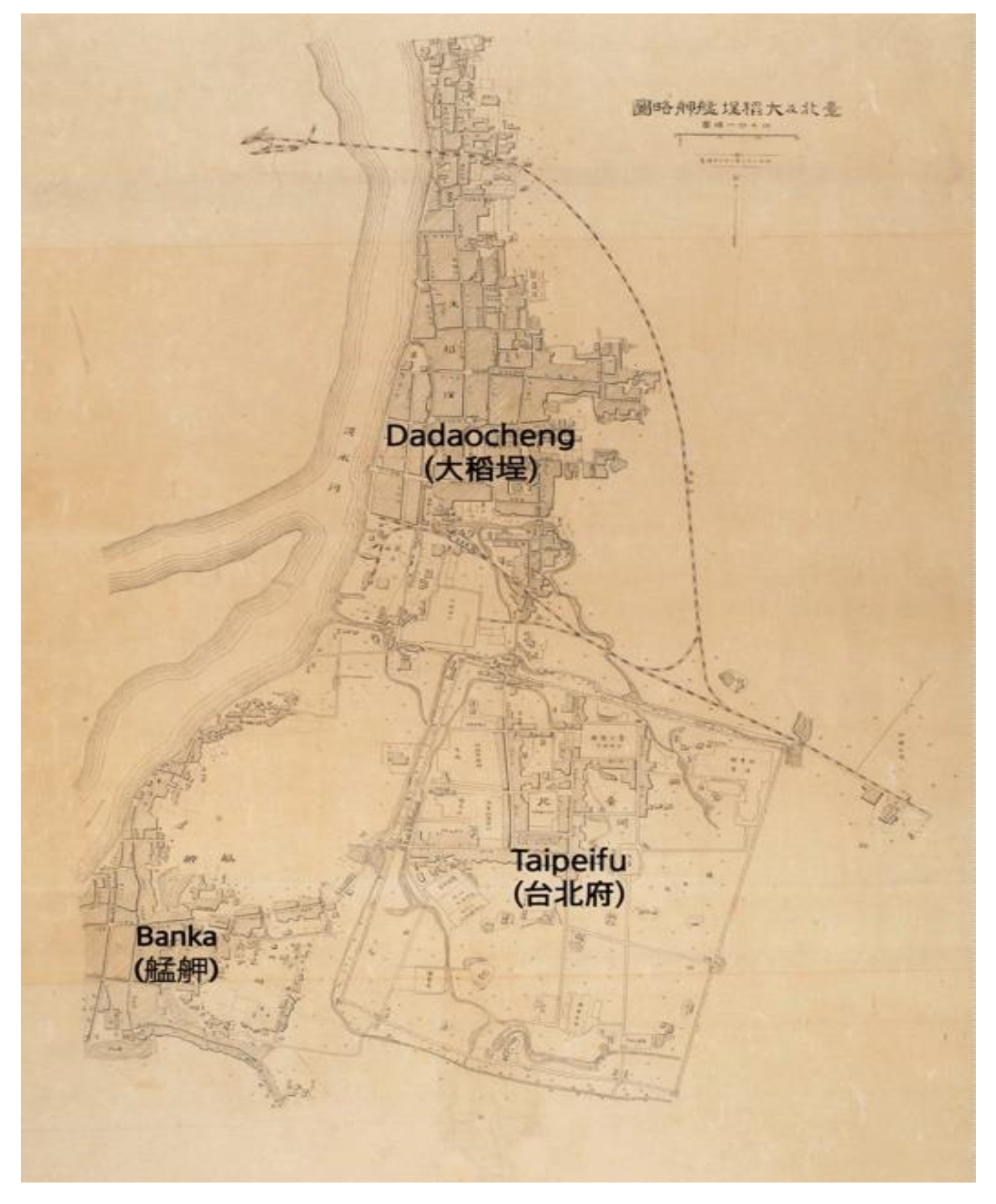

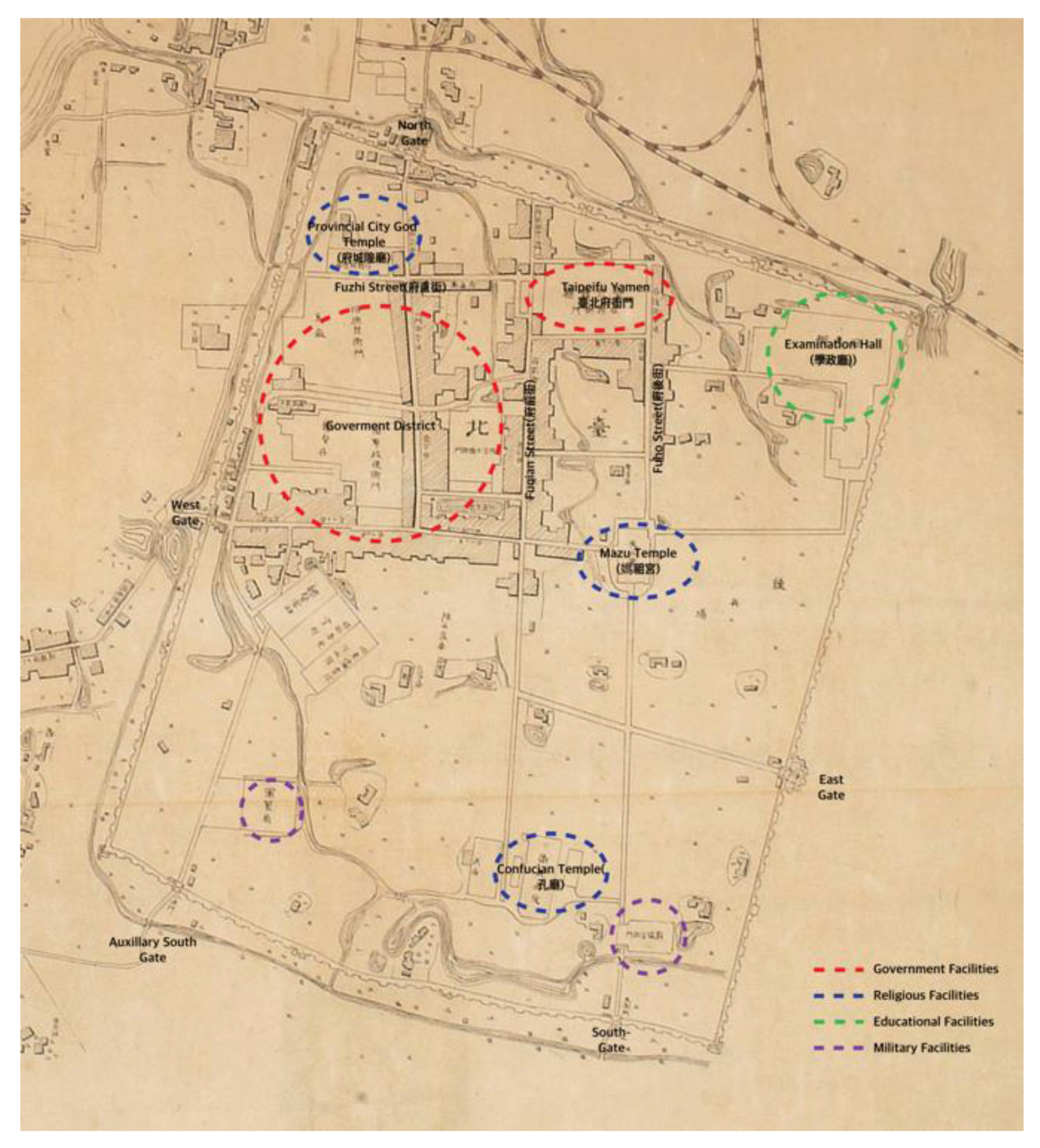

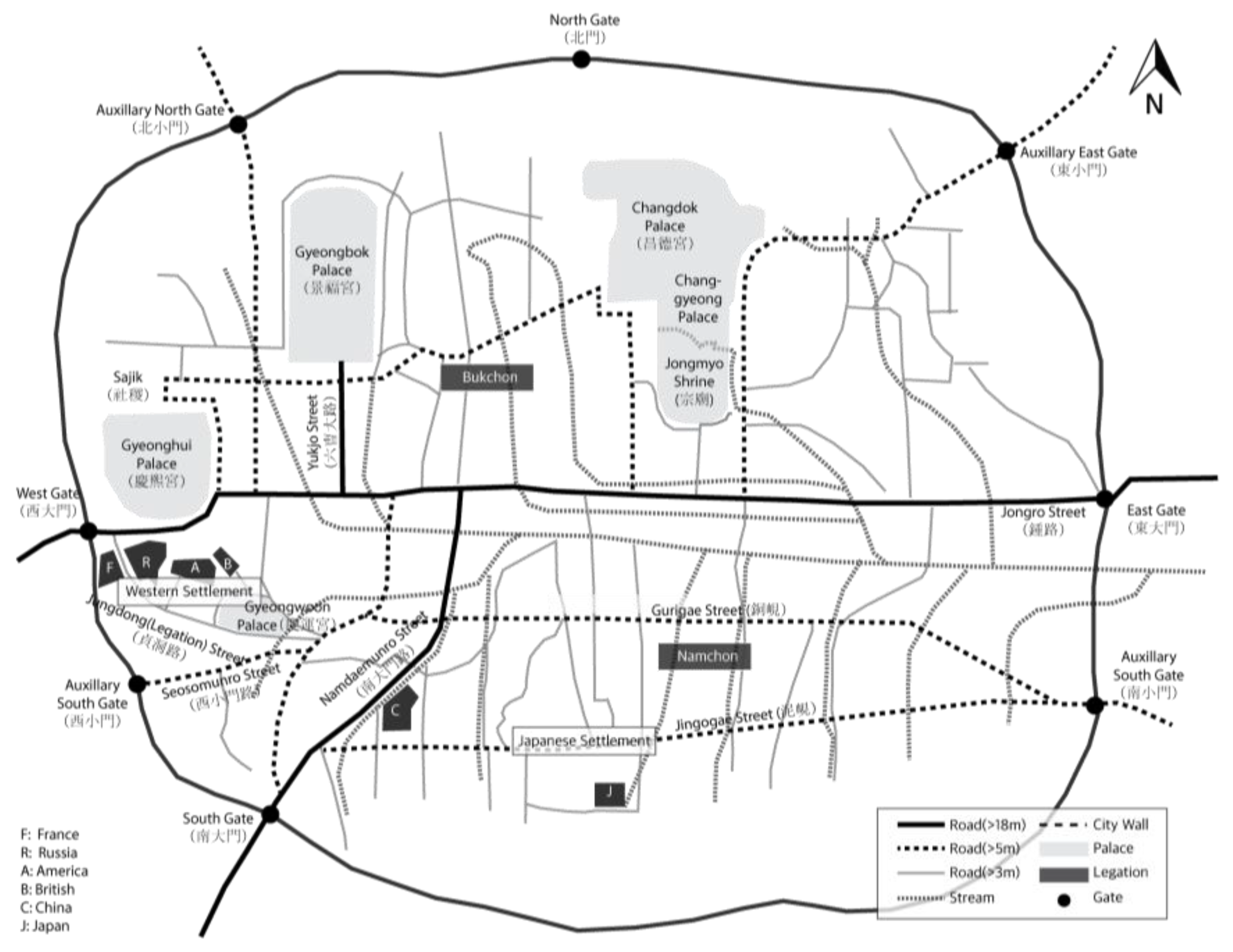

Before the Japanese occupation, Taipei and Seoul were walled cities built in accordance with traditional Chinese principles of city construction. Both cities had city gates facing north, south, east, and west. Government facilities were in the northern part of both cities. However, these two cities were fundamentally different. The original civic center of Seoul was inside the city wall, while the original urban settlements of Taipei were outside the city wall; inner-city Taipei had been built as a new Taipei-area civic center in 1879. In 1895, the Japanese empire established JGGT in the Taipei inner city. In 1910, Seoul finally became a Japanese colonial city, 28 years after Japanese settlers first invaded the southern part of Seoul. Thus, the colonization process of Taipei overlapped with the construction of a new town in the vacant south-east area of inner-city Taipei. By contrast, the transformation of Seoul into a colonial modern city began with the invasion of Japanese settlers, building into a gradual expansion into the traditional civic center.

After Japanese colonization in 1895, the population of Taipei increased rapidly. Specifically, the population of Taipei inner city, where the population grew fastest, tripled, rising from 3895 in 1896 to 11,370 in 1905. The population of the original settlements of Banka and Dadaocheng also increased. The total number of residents in the Taipei area, including the inner city, Banka, and Dadaocheng, doubled, growing from 46,710 in 1896 to 99,479 in 1905. The Japanese population, in particular, soared from 4256 in 1896 to 29,460 in 1905 (a sevenfold increase) [

26,

31]; as a proportion of the total population, the Japanese population grew from 9.1% to 29.6% in 10 years. During the early stage of the Japanese occupation, almost 73% of Japanese residents lived in the Taipei inner city. By 1905, however, the Japanese population of Banka exceeded that of Taipei inner city, due to the construction of a Japanese residential district outside the city wall, based on “City Planning of Southern Area outside Taihoku City” (台北城外南方市區計畫) in 1901. However, the population in Taipei inner city was predominantly Japanese: 72.8% in 1896, 87.2% in 1902, and 88.6% in 1905 [

25,

26,

31]; Taipei census data before and after the turn of the 20th century (

Table 2) show that Taipei inner city was a Japanese-dominated area, while the southern outskirts of Taipei inner city gradually became a mixed-residence quarter, with Taiwanese and Japanese residents.

Although Japanese people began living in Seoul in 1882, there were only 40 Japanese residents at that time. After the Sino-Japanese war, the Japanese population more than doubled, from 848 in 1895 to 1839 in 1896. After the Russo-Japanese war, the Japanese population was more than 10,000 in 1906 and 34,468 in 1910 [

48] (pp. 105–107). As the number of Japanese residents increased, the Japanese settlement area also expanded to include the southern area of Seoul and the Yongsan area, outside the Seoul city wall. Yongsan grew into the second Japanese settlement in Seoul after the Russo-Japanese war. The Japanese army took a large amount of land in Yongsan for military use and the construction of a railway in 1904. They built many facilities around the railway, including a railway station, hospital, school, and official residences. The population of Japanese residents in Yongsan increased rapidly from 1904 onwards. In 1904, the Japanese population consisted of 350 people. By 1905, it had increased to 1700, while in 1909, it was more than 10,000 [

49] (pp. 92–93).

Table 3 shows the demographics of Seoul by ethnic group in 1911 and 1913, following Japanese occupation. In 1911, there were 35,268 Japanese settlers—15.8% of the total population of Seoul inner city; in Yongsan, 59.6%of the total population was Japanese.

The distribution of Japanese settlements in Taipei and Seoul affected the urban structure of the two cities. In Taipei, the colonizer’s initial urban-planning project focused on Taipei inner city, where the colonial government was located, and most Japanese settlers lived. After 1905, urban planning in Taipei focused on creating an integrated urban system to link the Taiwanese-dominated areas of Banka and Dadaocheng with the Japanese area in inner-city Taipei by demolishing the city wall and building roads to connect the three urban centers of Taipei, Banka, and Dadaocheng with the inner city. As this was happening, the Japanese population of Banka and Dadaocheng continued to increase.

The growth of Yongsan transformed the spatial structure of Seoul. Yongsan was linked to the outer old Seoul (城底十里) and located on the south-west side of Seoul. When the modernization and colonization process began, Yongsan became a center for railway transportation and the second Japanese settlement in Seoul. It was necessary to enhance transportation conditions by improving the road between Yongsan and the South Gate of Seoul and tearing down part of the Seoul city wall around the South Gate. The 1912 urban improvement plan included the road toward Yongsan; in 1914, greater Seoul officially included the Yongsan area [

35] (p. 442). Thus, Seoul became characterized by an urban structure in which a new town protruded from the traditional walled city, resembling the typical colonial dual cities of Delhi and New Delhi [

4] (p. 188).

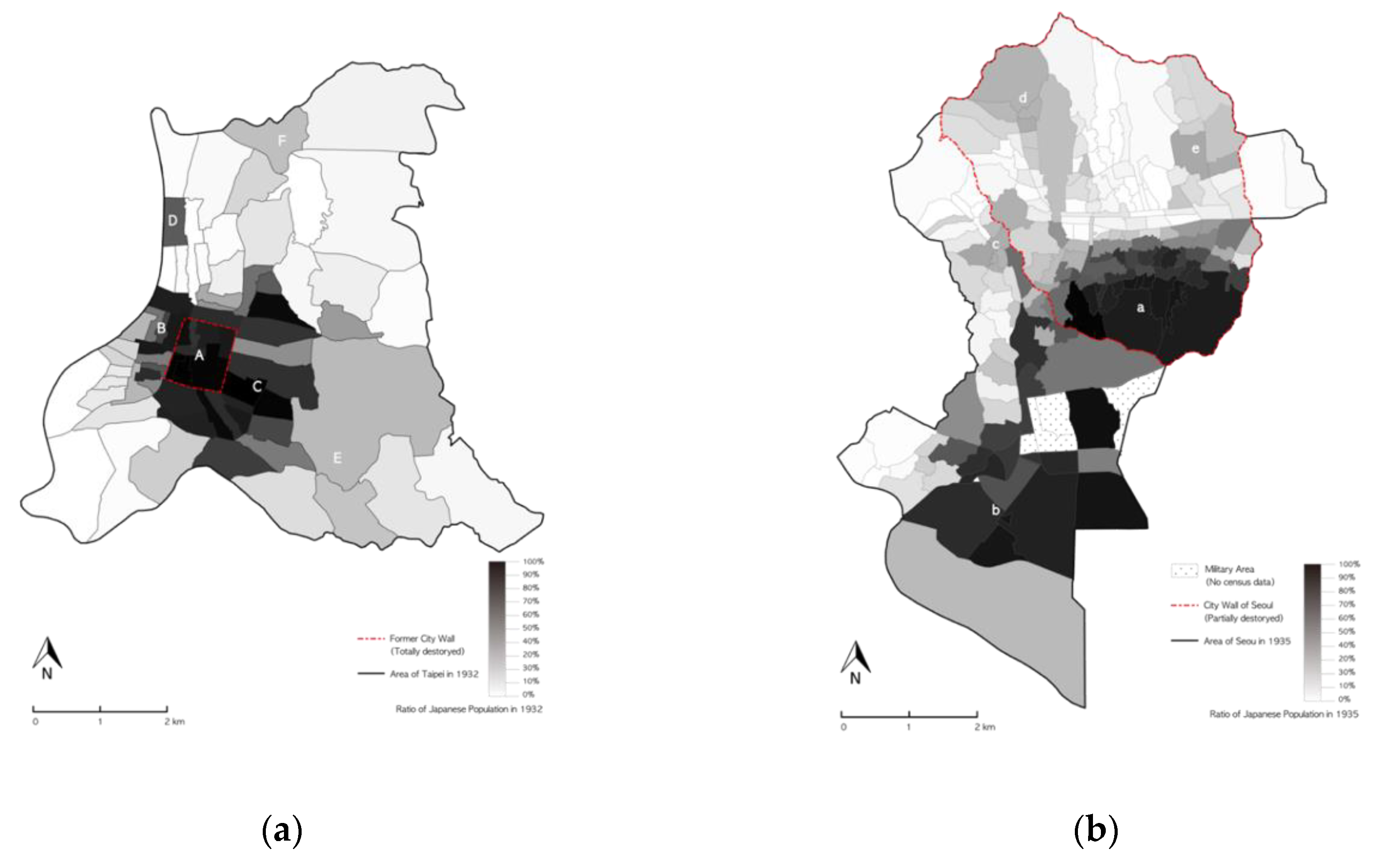

The residential areas allocated to the colonizer and colonized were not clearly divided into Taipei and Seoul, in contrast to Western colonial cities [

24].

Figure 4 shows the distribution of the Japanese population in Taipei in 1932 [

2,

27] and Seoul in 1935 [

29,

30]. In Taipei, Japanese people dominated the entire Taipei inner city (A), while the proportion of Japanese people was high in both areas between Dadaocheng and Banka (B) and also on the east side, adjacent to the former Taipei inner city wall (C), constructed after the initial period of urban planning in 1905. The remaining area was dominated by Taiwanese people. However, the ratio of Japanese people in Ohashicho (大橋町, D) was relatively high (62.61%) in comparison to its neighbors; the south-eastern (E) and north-eastern parts of Taipei (F) were mixed residential areas [

2]. In Seoul, Japanese people were dominant in Namchon (a) in the Seoul inner city, and also in the Yongsan area (b). However, the villages around the former West Gate (c), Gwanghwamun Street (d), and Keijo University (e) constituted a mixed residential area.

In conclusion, there was no apparent spatial separation by ethnic group in Taipei or Seoul. Both cities appeared to have three types of residential district: Japanese-dominated new towns, mixed Japanese and Taiwanese/Korean districts, and Taiwanese/Korean-dominated areas. Japanese colonial cities were unique in having large colonizer populations (Japanese people) from a range of social and economic classes. In Taipei and Seoul, Japanese people accounted for almost 30% of the whole population). Unlike colonizer populations in colonial cities under European rule, Japanese people looked very similar to colonized Koreans and Taiwanese.

4. Comparison of Urban Changes in Seoul and Taipei as They Became Modern Colonial Cities 2: Urban Planning

In 1895, the first urban-improvement projects were undertaken in both cities; however, different agents carried out these projects in Taipei and Seoul. This reflected the fact that Taipei was newly colonized in 1895, as a consequence of the first Sino-Japanese war, while Seoul was still independent at that time.

In 1895, Taipei was renamed “Taihoku” (台北) by the Japanese authorities. During the first ten years of colonization, the Japanese focused on rebuilding and improving buildings and streets. In 1895, drains were temporarily set up along the outer city walls; in 1896, an open sewage system was installed along the inner streets of Taipeifu City. While urban changes between 1895 and 1899 emphasized improvements to urban sanitation and safety, urban planning after 1900 was characterized by the introduction of new block systems in Taipei and the construction of Japanese residential areas on the southeastern side of Taipei (

Figure 5). In 1901, “City Planning for the Southern Area outside Taihoku City” (台北城外南方市區計畫), a plan for constructing a Japanese residential district, was extended to accommodate the increasing Japanese population [

16] (pp. 119–120).

In 1895, the Seoul government began to improve city roads and to build new ones, beginning its urban-improvement activities by demolishing illegal buildings on Namdaemunro and Jongno Streets in 1895. In 1896, Namdaemun and Jongno Streets were repaired and the roads around Gyeongwoon Palace, which became the main palace of the Daehan Empire after 1897, were improved. As urban-improvement projects were implemented between 1895 and 1897, the road system around Gyeongwoon Palace was constructed and readied for the introduction of new transportation facilities, such as trams in 1899. After 1901, however, the government’s urban-improvement projects had to stop, due to financial difficulties [

46,

47]. At the same time, Westerners repaired the main street of Jeongdong, where legations were based, while the Japanese improved streets in the Japanese settlement area. Japanese urban-improvement projects continued, as needed, until 1910 [

48] (p. 211–212) (

Figure 6).

The urban planning projects that led to the construction of colonial modern cities were announced for Taipei and Seoul in 1905 and 1912, respectively. In 1905, the Municipal Reform Project for Taihoku City (台北市區計畫) was announced. This urban-planning project was the first to cover the whole Taipei area, including the original settlement, Dadaocheng, and Banka. It aimed to cover 720 hectares of urban land, as the population was predicted to reach 150,000 by 1929. In this plan, the city walls were replaced with a 37–72 m ring boulevard. The inner-city grid street patterns were extended to the outer regions, while several roundabouts were planned as special nodes. The existing roads of Dadaocheng and Banka were to be straightened, with radial streets superimposed at some nodal points [

16] (p. 120), [

3] (p. 31,32) (

Figure 7).

The distinguishing characteristic of this plan was the demolition of the city walls. The Taipei city walls, completed in 1884, had become an obstacle to urban growth within a mere ten years. Between 1910 and 1913, the site of the city walls was replaced with three-lined boulevards. During the initial stage of urban planning to enlarge Taipei City, five city gates were in line be demolished. In the end, only the West Gate was removed because some Japanese officials and members of the Chinese elite argued that the gates should be preserved. As the preserved gates made it difficult to channel urban traffic, it was necessary to build rotaries around the gates [

3] (p. 76). While urban planning in 1900 and 1901 focused on the construction of Japanese government districts and residential districts in Taipei inner city, the 1905 plan aimed to connect newly constructed Japanese government and settlement areas in the east with the original Taiwanese regions in the west. Decisively, the demolition of city walls integrated three urban districts—the so-called

Sanxijie of Taipei inner city, Dadaocheng, and Banka—using modern urban technologies, including the grid system. Streets were improved throughout the Taipei region. The northwestern section of the inner city was reorganized into blocks with newly constructed orthogonal roads, while new streets were introduced to the undeveloped area between Dadaocheng and Banka. The Municipal Reform Project for Taihoku City (台北市區計畫) continued until 1932, when the Great Taihoku City Plan was announced. The project developed basic urban infrastructures for the modern city of Taipei [

2,

14,

16].

After 1910, the official name of Seoul was changed from Hansungbu to Keijobu. In 1912, the Keijo Civil Engineering Office promulgated the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan, which set out to straighten and widen the 29 lines [

50]. It was modified, with the addition of 15 lines, in 1919. During the period up to 1929, JGGK invested 5,792,000 won and constructed 21.3 km of road in total [

51] (p. 164). The initial Keijo Urban Improvement Plan (

Figure 8) had two major characteristics.

The grid system, with five north-south streets and four west-east streets, and the radial road system around five centers. (a–e) The west-east roads, apart from the sixth road (f), designed to link Changeuk Palace with Jongmyo Shrine, had been main city roads since the Joseon Dynasty. By contrast, the north-south roads, apart from Namdaemunro Street, were new. In contrast to the Hansungbu road system, which was organized around west-east roads (

Figure 3), the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan focused on the grid system by constructing new north-south main roads. The most radical element of this plan was the radial road system around Koganemachi Plaza. This was ultimately never built because the Japanese settlers who owned the planned site for the plaza and the roads rejected the design. The radial road system was ultimately excluded from the amendment plan of 1919 (

Figure 9) [

5] (pp. 17–24).

In the 1910s, the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan focused on improving the streets that connected villages to the south, where many Japanese people lived, with the traditional center of Seoul in the north. After the initial plan was modified in 1919, its primary focus became the improvement of streets to the north of Jongro Street [

4,

5,

21,

52]. This was due to the relocation of government facilities, including JGGK and the Keijofu offices, from Namsan Hill to central Seoul. Consequently, the civic center of Seoul was relocated from Namchon, where the JGGK office was located during the early years of colonization, to Bukchon. The 1919 amendment plan also included outbound roads to the outskirts of Seoul, such as Mapo and Yongsan. The map below shows the Seoul city plan, enlarged to include south-western areas. The Keijo Urban Improvement Plan functioned as the basic urban planning map of Seoul until 1936, when the Great Keijo City Plan was announced.

In sum, the 1905 Taihoku City Municipal Reform Project (台北市區計畫) aimed to connect a new civic center built by the Japanese colonizers on the east side with the original Taiwanese settlements in the west. The Keijo Urban Improvement Plan (京城市區改修) created a network to link the Japanese settlement in Namchon with the original civic center of Seoul in Bukchon. Although these urban plans were different in their details, both plans set out to construct urban networks and street improvements. In both cities, new modern blocks incorporated orthogonal road systems; partially radial road systems were built around rotaries, which were urban nodes, such as former city gates or newly built plazas. In addition, engineers enhanced the streets in both cities by expanding road width, refining road conditions, and installing water and sewage systems. It can be assumed that urban planning in Seoul was influenced by previous experiences in Taipei, since the official head of the groups that designed and executed urban planning in Seoul was Mochiji Rokusaburo (對地六三郎) [

50] (pp. 193–184), who had previously worked in Taiwan. These two plans were used to provide basic urban planning in both cities until the 1930s, when the Great Taihoku Plan was announced in 1932 and the Great Keijo Plan in 1936.

Although urban planning had similar aims in Taipei and Seoul, differences in the colonization of the two cities had an impact on the execution of modern projects. The first Japanese settlement in Taipei was constructed in a vacant area in Taipei inner city. By contrast, the Japanese settlement in Seoul was located inside the original Korean village at the start of colonization. This made a critical difference between urban changes in Taipei and Seoul, as they moved toward becoming modern colonial cities.

In Taipei, the first Japanese settlement was built around the same time as the colonial government facilities and thus became the center of Taipei City. By the time of the Municipal Reform Project for Taihoku City, the vacant wetland in the east was becoming urbanized on a large scale. Most of the residents of the newly developed eastern districts were Japanese. As the eastern part of colonial Taipei City, where the Japanese settled down from the beginning stage of colonization, was gradually filled with colonial government facilities, hospitals, schools, and Japanese residences, the area had become a civic center.

By contrast, many Japanese merchants and businessmen settled and built neighborhoods in Seoul before the colonization project truly began, after the Russo-Japanese war. Japanese government facilities were temporarily located near the Japanese settlement in 1910. As the Japanese neighborhood Namchon had no geographical or political advantages, it was necessary to move the colonial government facilities, including the JGGK office, to the old civic center in the north. This caused a shift from the south to the north and a spatial separation between the Japanese government-facilities site and the original Japanese settlement.

In conclusion, urban planning in Taipei aimed to integrate the original Taiwanese areas and vacant paddle fields with the new area populated by Japanese people. By contrast, Japanese urban planning in Seoul focused on making inroads into the original Korean civic center

Figure 10.

Figure 11 show the Taipei and Seoul urban-planning transformation process.

5. Comparison of Urban Changes in Seoul and Taipei as They Became Modern Colonial Cities 3: Modern Boulevard Showing the Colonizer’s Spectacle

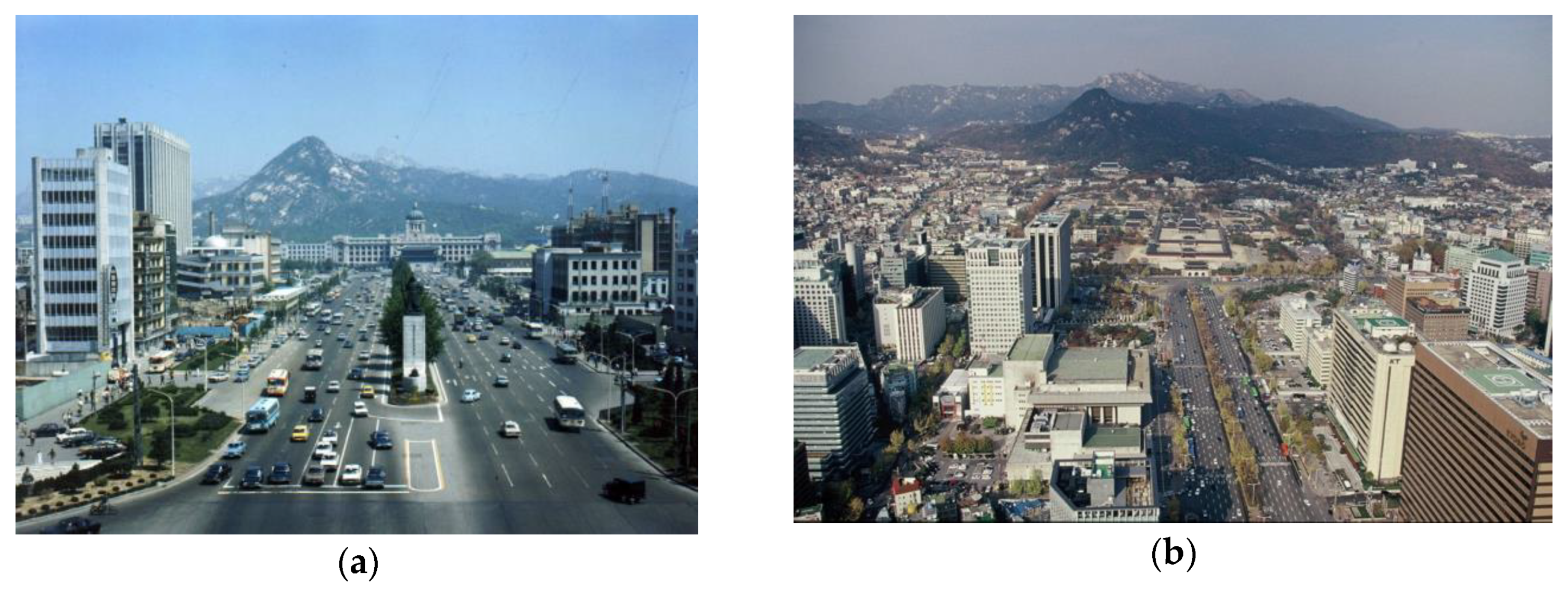

The most tangible achievement of the Taihoku City Municipal Reform Project (台北市區計畫) in 1905 and the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan (京城市區改修) was the construction of modern boulevards in both cities. The representative three-lined ring boulevards (Sansenro, 三線路) [

14] are the boulevard in front of the JGGT building in Taipei and Gwanghwamun Boulevard (present-day Sejongro Boulevard) and Taihei Boulevard (present-day Taepyeongro Boulevard) in Seoul [

4,

21].

In Taipei, the Taipei city wall was displaced by Sansenro, which resembles the boulevards of Paris, having three lanes of traffic separated by a safety island and two lines of trees. As Allen has pointed out, Sensenro transformed Taipei from a traditional Chinese bureaucratic center into a symbolic place of colonial modernity [

3] (p. 76). The middle parts of these roads were parkway, planted with a diverse selection of trees: Palm trees in the east, maple trees in the west, cedar trees in the south, and anemone trees in the north. People enjoyed walking in Sansenro, as the popular 1930s Taiwanese song, Guehyiatshiu (Gloomy Moonlight, 月夜愁) describes: “月色照在 三線路 風吹微微 等待的人那未來 The moonlight shines on the three-lined boulevards, the wind blows slightly. It is the future that everyone is waiting for”.

East Sansenro (present-day Zhongshan South Road, Figure 14a) was the most significant boulevard, as key modern colonial facilities, including the Taihoku Prefectural Office, Taihoku Hospital, Red Cross Hospital, Taihoku Medical School, and Taihoku New Park were located along east Sansenro (

Figure 12).

In addition, the Great Taihoku Plan (

Figure 13), which expanded developments toward the east further enhanced the dominance of the East Gate and JGGT Boulevard. The modern streetscapes of Taipei City featured straight, wide roads and new Western classical-style buildings. As Wu Pingsheng has explained, “with newly-built boulevards, a scene and atmosphere of modern urbanism was created, revealing the intentions of the colonizer to build a successful colonial city, a new Taipei City” [

16] (p. 185).

After 1919, when the symbolic JGGT building, which symbolized Japanese colonial power, was completed, both the boulevard and the East Gate (present-day Ketagalan Boulevard, 凱達格蘭大道,

Figure 14b and

Figure 15a,b) became more important than the West or North Gates.

Taihei Boulevard was built in 1912 when the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan was implemented in Seoul (

Figure 16a). Taihei Boulevard was linked to the north end of Gwanghuamun Boulevard. The new street connected Kyungobok Palace to the South Gate through a straightforward boulevard. Taihei Boulevard was the first street in Seoul to be lined with trees and modern facilities, including the Keijo and Maeil Newspaper buildings. After the construction of Taihei Boulevard, Gwanghuamun Plaza (located at the intersection with Jongro Street) was expanded between 1913 and 1918. In 1924, Seoul City Hall was moved from Namdaemun Street to Taihei Street (

Figure 16b).

In 1926, the JGGK office building finally opened after seven years of construction (beginning in 1919). Then the project to improve Gwanghwamun Boulevard began. Gwanghwamun Gate, the main gate of Gyeongbok Palace, was moved to the eastern side of the palace (

Figure 17a,b). The boulevard was widened to 62 m, making space for a tram line. Street trees were planted along both sides [

34] (p. 176), [

53,

54]. The model of the Gwanghwamun Street Improvement Project included the boulevard in front of the JGGT building [

55].

Finally, in the late 1920s, Gwanghwamun and Taihei Boulevards became modern civic centers, with Western-style office buildings lining the streets. The majestic JGGK building stood at the north end of this modern boulevard, while the route to the South Gate passed Gwanghwamun and Keijofumae Plazas (

Figure 18).

Outside the South Gate, Taihei Street intersected with the road to Yongsan and Yeongdeungpo in the Great Keijo Plan (

Figure 19). In other words, Gwanghwamun and Taihei Boulevards had become the main north-south axis of Seoul, simultaneously presenting a modern streetscape and an imperial spectacle. However, unlike people in Taipei, the colonized population of Seoul felt repulsed by the construction of Gwanghwamun Boulevard and the JGGK building because builders had demolished the main gate of the Joseon Dynasty Palace. The Korean novelist Park Taewon described the Gwanghwamun Boulevard as an awkward wide and solitary road in his novel

A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist [

56] (p. 138).

The modern boulevards built by the Japanese empire in Taipei and Seoul were examples of modern urban planning, as well as colonization projects. The street environment was very similar on the boulevards of Taipei and Seoul. The colonized people who walked those boulevards absorbed the essence of colonial modernity. Both Sodofumae and Gwanghwamun Boulevards were very wide streets, lined with trees, street lamps, utility poles, and modern buildings. At their zenith, they housed Japanese government buildings, displaying their magnificent power. This type of scenery and atmosphere was typical of the main streets of Japanese colonial cities, which included Shinjing (新京), the capital of Manchukuo, as well as Taipei and Seoul. After the liberation of Korea in 1945, Sodofumae Boulevard was renamed Jieshoulu (介壽路), meaning “long live Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石)”, while Gwanghwamun Boulevard was renamed Sejongro, after Sejong, the fourth Joseon Dynasty king, who invented the Korean alphabet. These boulevards continue to be the most important political and social streets in Taipei and Seoul, despite some minor differences between them.

After liberation from Japan, Taipei and Seoul endured the Chinese Civil War and Korean War, respectively. When these wars eventually ended, the Taiwanese and Korean governments made every effort to overcome their colonial past and restore native traditions. Japanese-style street and town names were replaced by indigenous but political names, such as Jieshulu and Sejongro [

57]. The JGGT and JGGK buildings became Taiwanese and Korean government offices, while other government buildings were also reused [

3] (p. 76–77), [

58] (p. 86, 277). In the 1960s, the city gates of Taipei, apart from the North Gate, were demolished for not being Chinese enough, and replaced with gates in the North-Palace style [

3] (p. 78) (

Figure 20).

In Seoul, Gwanghwamun Gate was restored in front of the former JGGK building, using the modern material of reinforced concrete (

Figure 21a). These renovation projects were seen as government-led projects to recover and restore national legitimacy. In the mid-1990s, there were outstanding issues in both cities. In Taipei, Jieshulu Boulevard was renamed Ketagalan Boulevard in 1996, when Chen Shuibian (陳水扁), who ended the Kuomintang’s rule in Taiwan, was the mayor of Taipei. The gate was named in honor of the Ketagalan Taiwanese Aboriginal people who lived in the Taipei area. In Korea, the JGGK building was demolished in 1996 by President Kim Youngsam, on the grounds that it symbolized Japanese imperialism (

Figure 21b).

6. Conclusions

This study set out to discover how the Japanese empire transformed the traditional capital cities of Taiwan and Korea into modern colonial cities by comparing two cities, Taipei and Seoul. The comparison incorporated three strands: The spatial distribution of ethnic groups, urban planning, and the modern boulevard. The process through which Taipei and Seoul were transformed into colonial cities under Japanese rule can be analyzed in the following three ways.

First, at an early stage of colonization, Japanese residential areas influenced the growth of colonial Taipei and Seoul. As colonization progressed, the number of Japanese settlers grew rapidly. It was necessary to build new residential areas for Japanese people, such as the south-eastern village of Taipei and Yongsan in Seoul. In addition, Japanese people moved into older residential areas, such as Banka and Dadaocheng in Taipei and Bukchon in Seoul. Due to a high proportion of Japanese residents in both cities (about 30% of the population), Japanese people lived in most parts of Seoul and Taipei. Thus, there was little spatial segregation between the colonizer and colonized peoples, unlike the pattern in colonial cities under European rule. Instead, there were three types of areas: Japanese dominated areas, Korean/Taiwanese-dominated areas, and mixed residential areas. The multi-core structure of Taipei and Seoul affected modern Japanese colonial urban planning.

Second, the 1905 Municipal Reform Project for Taihoku City (台北市區計畫) and the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan (京城市區改修), the first examples of modern urban planning executed by Japanese colonial governments in the two cities, aimed to connect dispersed civic centers and to create orthogonal road systems, partially supplemented with shared rotaries and plazas. Although the location of Japanese settlements influenced urban planning in Taipei and Seoul, the details were different in the two cities. The Keijo Urban Improvement Plan had to be modified in 1919 when the colonial government facilities moved. By contrast, the Municipal Reform Project for Taihoku City was carried out without much amendment until the Great Taihoku Plan in 1932, as the colonial municipal center remained in the same place throughout the colonial period. Consequently, the Keijo Urban Improvement Plan focused on improving the traditional center of Seoul, while the Municipal Reform Project for Taihoku City emphasized outward expansion, beyond the demolished city walls.

Third, the modern boulevards, colonial products of modern urban planning, became representative urban places that showcased colonial modernity. The Ketagalan-Zhongshan South Boulevards of Taipei and the Sejong-Taepyeong Boulevards of Seoul continue to be the most important boulevards in Taipei and Seoul. They revealed the power of colonial authority by transforming the traditional urban structures of both cities and offering their citizens a sense of modernity, despite the differences between Taiwanese, Korean, and Japanese people. When the Japanese empire that controlled both cities during the first half of twentieth century was replaced by democratic governments, the two typical modern boulevards of Taipei and Seoul continued to serve as important urban places, where major facilities were located. Many people gather in the plazas beside the boulevards during political and cultural events. The dramatic changes after liberation gave the boulevards an additional meaning: The restoration of national identity to overcome dark memories of colonial power. These boulevards have been transformed from symbolic places that displayed colonial modernity during the first half of the twentieth century into representative places that showcase democracy in Taiwan and South Korea.

In conclusion, along with the boulevards, much of the urban space and spatial structure developed during the Japanese colonial era can still be seen in Taipei and Seoul, even though many buildings were demolished to clear away the remnants of Japanese colonialism for urban development. The old civic centers of Taipei and Seoul represent urban transformation, demonstrating both colonization and restoration processes in two modern cities. Furthermore, the living environments designed during the colonial period to narrate urban history continue to be essential parts of present-day Taipei and Seoul. For instance, the Japanese residential areas, including the Qing-Tian Jie (靑田街) in Taipei [

61] and the Hu-Am Dong (厚岩洞) in Seoul [

61], are well preserved. These places have been placed in the spotlight by urban regeneration in the 21st century. However, despite their importance, our knowledge of colonial-era urban structure and artifacts remains fragmentary. Some colonial heritage is under threat of demolition because many Koreans (and some Taiwanese) still harbor hostility toward the colonizer, Japan. Comparative studies of Taipei and Seoul can help us understand Japanese colonial modern cities, which differ in many respects from Western colonial cities. Both cities were modernized with introduction of modern urbanization system and technologies; however, at the same time, they showed the characteristics of colonial cities including spatial distribution by ethnic groups, multi-core urban structure, and the modern boulevard showing imperial spectacle in common. It means that the present urban conditions of two cities are very complicated, because the areas of the colonizer and the colonized were not separated and the modern transformation process has continued based on colonial urban planning after the liberation. Thus, such studies can unearth the meaning and value of colonial remnants including urban structure and artifacts for the sustainable future of each city, because it is not impossible to totally erase the colonial remnants of each city.