Does Corporate Governance Affect the Quality of Integrated Reporting?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Corporate Governance and Reporting Quality

2.2. Integrated Reporting (IR)

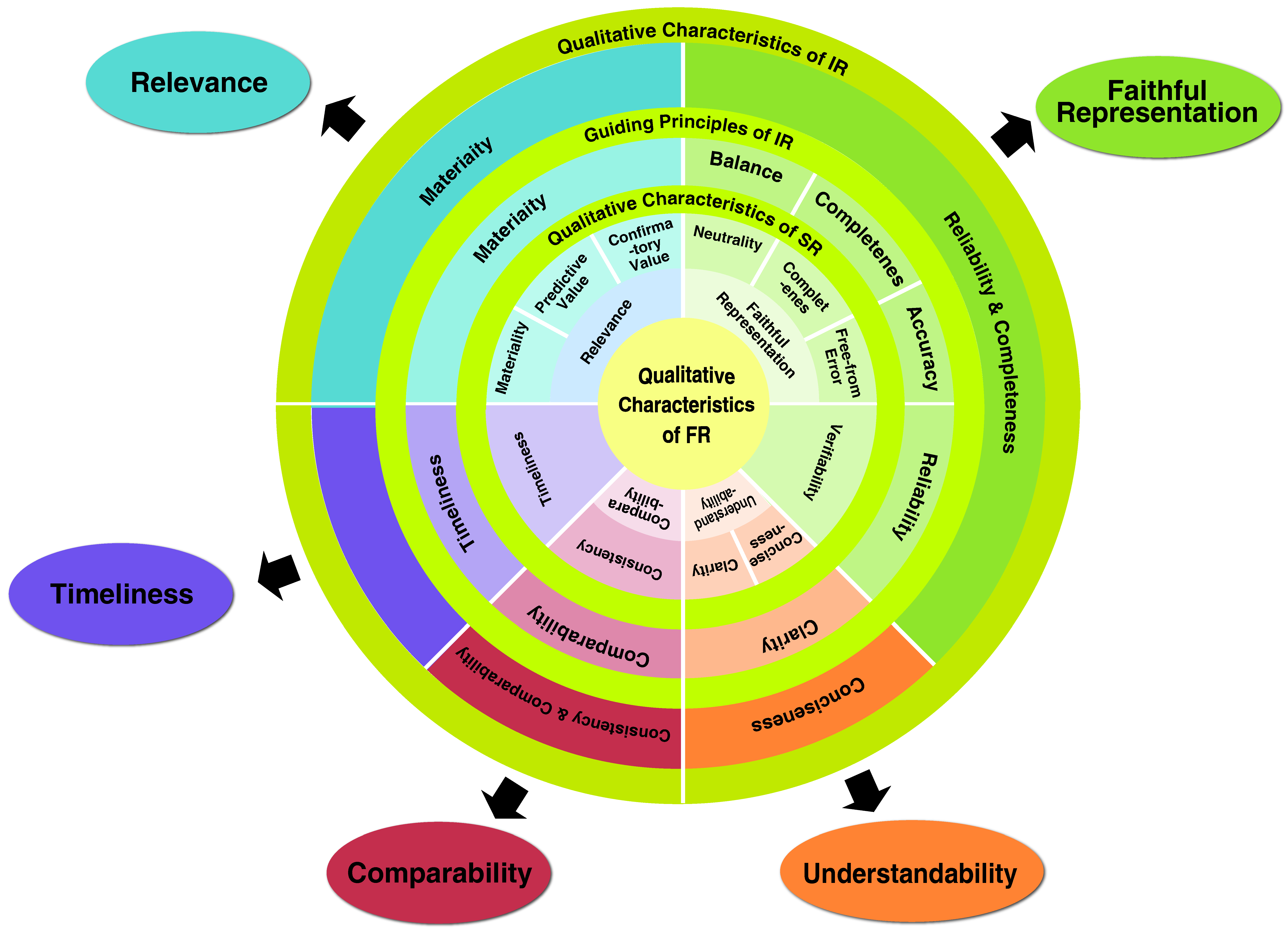

2.3. Integrated Reporting Quality (IRQ)

2.4. Agency Theory

3. Hypotheses Development

4. Methodology and Measurement

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.1.1. Industry-Wise IRQ Score

5.1.2. Overall Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Correlation Analysis

5.3. Panel Regression Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

8. Notes

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Qualitative Characteristics | Items | Operationalization | Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relevance | The extent of information included on: | ||

| 1. Relevant material issues. The determination of material issues based on the four steps of materiality determinant process. | 0 = No disclosure. 1 = Only relevant material issues identified. 2 = Relevant material issues with magnitude-likelihood diagram presented. 3 = If first, second and third steps presented. 4 = If all four steps presented. | [30,135,136] | |

| 2. Organization’s overview and external environment. Should include: mission and vision/goals and objectives; culture, ethics and values; ownership and operating structure; principal activities and markets; competitive landscape and market positioning; position within the value chain; and key quantitative information highlighting significant changes from prior periods. | 0 = No disclosure. 1 = Less than three items. 2 = Three to five items. 3 = Six to seven items. 4 = All seven items explained with reference to the relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. | [30] | |

| 3. Various market events and significant transactions affect the company. | 0 = No feedback. 1 = Only various market evets. 2 = Events, transactions and impact on qualitative or quantitative terms. 3 = Events, transactions and impact both in qualitative and quantitate terms. 4 = Events, transactions and impact both in qualitative and quantitate terms with reference to the relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. | [28,30,135,137] | |

| 4. Economic/financial, social and environmental performance of the company (in terms of Key Performance Indicators [KPIs]). | 0 = No analysis. 1 = Only financial information. 2 = Financial + social or environmental information. 3 = Financial + social and environmental information. 4 = Financial + social and environmental information with reference to relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. | [30,137,138] | |

| 5. Relevant capitals. | 0 = No disclosure. 1 = Identified but not relevant to the organization. 2 = Relevant capitals merely identified. 3 = Relevant capitals identified and described but not referred to relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. 4 = Relevant capitals identified and described with reference to relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. | [30,139] | |

| 6. Divisional performances. | Same as 1.4. | [30,87,138,139,140] | |

| 7. Outlook of the company. Should include:

| 0 = No disclosure. 1 = Only (a). 2 = Both (a) and (b). 3 = All three. 4 = All three disclosed with reference to relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. | [30,87] | |

| 8. Risk profile of the company. Specific risks and opportunities that affect the organization’s ability to create value, and how is the organization dealing with them. | 0 = No insights into risk profile. 1 = Only the relevant risks and opportunities identified. 2 = Relevant risks and opportunities identified with sources of risk. 3 = Relevant risks, their sources identified, and a risk assessment provided. 4 = Relevant risks, their sources are identified, a risk assessment, and risk management plan provided. | [30,87,141] | |

| 2. Faithful representation | The extent of valid arguments provided on: | ||

| 1. Assumptions and estimates. For financial/economic or social and environmental information. | 0 = No valid arguments; 1 = Poor argument; 2 = Average argument; 3 = Good argument; 4 = Excellent argument. | [30,85,87,142] | |

| 2. Choice for certain accounting, environmental and social policies. | Same as above. | [85,87,142] | |

| 3. Corporate governance and its impact on value creation. Should include: 1. Leadership structure; 2. Processes used to make strategic decisions and establish and monitor the culture; 3. Particular actions taken to influence and monitor the strategic direction; 4. How the organization’s culture, ethics and values are reflected in its use of and effects on the capitals; 5. Implementation of governance practices that exceed legal requirements; 6. The responsibility for promoting and enabling innovation; 7. How remuneration and incentives are linked to value creation. | 0 = No disclosure. 1 = Only one item. 2 = Two to four items. 3 = Five to six items. 4 = All seven items with reference to the relevant IR guiding principles and value creation process. | [30,85] | |

| 4. Positive and negative events. Financial/ economic, social and environmental information. | 0 = Negative events only. 1 = Emphasis on positive events. 2 = Emphasis on positive events, but negative events mentioned. 3 = Balance positive/negative events. 4 = Impact of these events to the value creation process. | [16,87,143] | |

| 5. Type of the auditors’ report for financial information. | 0 = No opinion given; 1 = Adverse opinion; 2 = Disclaimer of opinion; 3 = Qualified opinion; 4 = Unqualified opinion. | [142,144,145] | |

| 6. Type of assurance for social and environmental information. | Same as above. | [87,89] | |

| 3. Understandability | The extent of the description provided on, | ||

| 1. Business model. Should include: 1. Explicit identification of the key elements; 2. A simple diagram highlighting key elements with an explanation; 3. Logical narrative flow; 4. Identification of critical stakeholder and other dependencies affecting the external environment; 5. Connection to information covered by other content elements. | 0 = No description. 1 = Only identified the key elements. 2 = First three items. 3 = First four items. 4 = All items. | [30,146] | |

| 2. Strategy and resource allocation. Should include: 1. Short-, medium- and long-term strategic objectives; 2. The strategies to achieve those strategic objectives; 3. The resource allocation plans; 4. Measure of achievements and target outcomes. | 0 = No description; 1 = Two or less than two items; 2 = Three items; 3 = All items; 4 = All items and linkages with capitals, other content elements provided. | [30,87,137] | |

| 3. Basis of preparation and presentation of integrated report. Should include: 1. Materiality determination process; 2. Reporting boundary and determination; 3. Frameworks/methods used to decide material matters. | 0 = No description. 1 = Only one of the matters with inadequate information. 2 = Two matters with incomplete information. 3 = All matters described, but gaps exist. 4 = All matters included with complete information. | [30,147] | |

| 4. The extent to which the graphs and/or tables clarify the presented information. | 0 = No graphs and/or tables; 1 = 1–10 graphs and/or tables; 2 = 11–20 graphs and/or tables; 3 = 21–30 graphs or/tables; 4 ≥ 30 graphs and/or tables. | [87,137] | |

| 5. Extent of the technical jargons provided. | 0 = Very extensive; 1 = Extensive; 2 = Moderate; 3 = Limited; 4 = No/hardly. | [30,85,137] | |

| 6. Size of the glossary. | 0 = No glossary; 1 = Less than 1 page; 2 = Approximately 1 page; 3 = 1–2 pages; 4 ≥ 2 pages. | [85,137] | |

| 7. Number of pages in the report. | 0 = More than 200; 1 = From 151 to 200; 2 = From 101 to 150; 3 = From 51 to 100; 4 = Up to 50. | [3] | |

| 4. Comparability | The extent of information included about, | ||

| 1. Changes in accounting and non-accounting policies. | Same as 1.4. | [30,85,89] | |

| 2. Changes in accounting and non-accounting estimates. | Same as above for estimates. | [30,85,89,148] | |

| 3. Comparison and effects of accounting and non-accounting policy changes. | 0 = No comparison; 1 = Actual adjustments (1 year); 2 = 2 years; 3 = 3 years; 4 = 4 or more years. | [30,85,89,149] | |

| 4. Financial/economic index numbers and ratios. | 0 = No comparison; 1 = Only with previous year; 2 = With 5 years; 3 = 5 years + description of implications; 4 = 10 years + description of implications. | [85,150] | |

| 5. Social and environmental indices and ratios. | Same as above. | [87,89] | |

| 6. Competitors and/or industry. | 0 = No ratios; 1 = 1–5 ratios; 2 = 6–10 ratios; 3 = 11–15 ratios; 4 ≥ 15 ratios. | [87,151] | |

| 7. Comparison of the financial/ economic results with previous reporting periods. | Same as above. | [85,149,150] | |

| 8. Comparison of the social and environmental performance results with previous reporting periods. | Same as 1.4. | [87,89] | |

| 5. Timeliness | 1. Number of months taken to publish the integrated report. | 0 = 5 or more; 1 = 4; 2 = 3; 3 = 2; 4 = 1. | [145,152] |

References

- Perego, P.; Kennedy, S.; Whiteman, G. A lot of icing but little cake? Taking integrated reporting forward. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 3–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Venter, E.R.; Hsiao, P.C.K. Integrated reporting: Background, measurement issues, approaches and an agenda for future research. Account. Financ. 2017, 57, 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistoni, A.; Songini, L.; Bavagnoli, F. Integrated reporting quality: An empirical analysis. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 24, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACCA. Insights into Integrated Reporting, Challenges and Best Practice Responses. 2017. Available online: www.accaglobal.com (accessed on 16 July 2018).

- Eccles, R.G.; Krzus, M.P. The Integrated Reporting Movement: Meaning, Momentum, Motives, and Materiality; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gunarathne, N.; Senaratne, S. Diffusion of integrated reporting in an emerging South Asian (SAARC) nation. Manag. Audit. J. 2017, 32, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stent, W.; Dowler, T. Early assessments of the gap between integrated reporting and current corporate reporting. Meditari Account. Res. 2015, 23, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.W.; Yeo, G.H.H. The association between integrated reporting and firm valuation. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2016, 47, 1221–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Simnett, R.U.; Green, W. Does integrated reporting matter to the capital market. Abacus 2017, 53, 94–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garegnani, G.M.; Merlotti, E.P.; Russo, A.A. Scoring firms’ codes of ethics: An explorative study of quality drivers. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 541–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. Value Creation: The Journey Continues: A Survey of JSE Top-40 Companies’ Integrated Reports. 2014. Available online: http://www.pwc.co.za/en_ZA/za/assets/pdf/integratedreporting-survey-2014.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Cadbury, S.A. The corporate governance agenda. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2000, 18, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, C.A. The Sustainable Development Goals, Integrated Thinking and the Integrated Report. 2017. Available online: www.iirc.org (accessed on 16 July 2018).

- Pavlopoulos, A.; Magnis, C.; Iatridis, G.E. Integrated reporting: Is it the last piece of the accounting disclosure puzzle. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2017, 41, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Htay, S.N.N.; Salman, S.A.; Meera, A.K.M. Let’s Move to” Universal Corporate Governance Theory. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2013, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.R.; Krishnamoorthy, G.; Wright, A. The corporate governance mosaic and financial reporting quality. J. Account. Lit. 2004, 23, 87–152. [Google Scholar]

- Klai, N.; Omri, A. Corporate governance and financial reporting quality: The case of Tunisian firms. Int. Bus. Res. 2011, 4, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R.; Zainuddin, Y.H.; Haron, H. The relationship between corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance characteristics in Malaysian public listed companies. Soc. Responsib. J. 2009, 5, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalaki, P.; Didar, H.; Riahnezhad, M. Corporate Governance Attributes and Financial Reporting Quality: Empirical Evidence from Iran. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, M.; Rashid, K. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting: An empirical evidence from commercial banks (CB) of Pakistan. Qual. Quant. 2014, 48, 2501–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, R.L.; García-Meca, E.; Martínez, I. Corporate governance and intellectual capital disclosure. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 100, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, L.L.; Tejedo-Romero, F.; Craig, R. Corporate governance and intellectual capital reporting in a period of financial crisis: Evidence from Portugal. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2017, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatridis, G.E. Environmental disclosure quality: Evidence on environmental performance, corporate governance and value relevance. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2013, 14, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathy Rao, K.; Tilt, C.A.; Lester, L.H. Corporate governance and environmental reporting: An Australian study. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2012, 12, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, A.; Lee, S.P.; Devi, S.S. The influence of governance structure and strategic corporate social responsibility toward sustainability reporting quality. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelon, G.; Parbonetti, A. The effect of corporate governance on sustainability disclosure. J. Manag. Gov. 2012, 16, 477–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P.F.; Caykoylu, S. Determinants of Companies that Disclose High-Quality Integrated Reports. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beest, F.; Braam, G.; Boelens, S. Quality of Financial Reporting: Measuring Qualitative Characteristics; Nijmegen Center for Economics (NiCE): Nijmegen, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 9–108. [Google Scholar]

- Santis, S.; Bianchi, M.; Incollingo, A.; Bisogno, M. Disclosure of Intellectual Capital Components in Integrated Reporting: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Integrared Reporting Council. The International <IR> Framework. 2013. Available online: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- ACCA. Tenets of Good Corporate Reporting. 2018. Available online: www.accaglobal.com (accessed on 16 July 2018).

- Roxana-Ioana, B.; Petru, S. Integrated Reporting for a Good Corporate Governance. ‘Ovidius’ University Annals. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2017, 17, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Gunarathne, N.; Senaratne, S. Country readiness in adopting Integrated Reporting: A Diamond Theory approach from an Asian Pacific economy. In Sustainability Accounting in the Asia Pacific Region; Lee, K., Schaltegger, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 39–66. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Report on the Observance of Standards and Codes; Accounting and Auditing- Sri Lanka: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Senaratne, S.; Gunaratne, P.S.M. Corporate Governance Development in Sri Lanka: Prospects and Problems. In Proceedings of the International Research Conference on Management and Finance, Faculty of Management and Finance, University of Colombo, Colombo, Sri Lanka, 11 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Chartered Accountants of Sri Lanka. Code of Best Practices on Corporate Governance. 2017. Available online: https://www.casrilanka.com/casl/images/stories/2017/2017_pdfs/code_of_best_practice_on_corporate_governance_2017_final_for_web.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Melloni, G.; Caglio, A.; Perego, P. Saying more with less? Disclosure conciseness and completeness in Integrated Reports. J. Account. Public Policy 2017, 36, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. A survey of corporate governance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 737–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K.; Senbet, L.W. Corporate governance and board effectiveness. J. Bank. Financ. 1998, 22, 371–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbach, M.S. Outside directors and CEO turnover. J. Financ. Econ. 1988, 20, 431–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolk, A.; Pinkse, J. The integration of corporate governance in corporate social responsibility disclosures. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2010, 17, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). OECD Principles of Corporate Governance; OECD: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jizi, M.I.; Salama, A.; Dixon, R.; Stratling, R. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from the US banking sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 125, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, F.; Khurshid, M.K.; Shakeel, M. Factors affecting the corporate governance disclosure: An analysis of manufacturing firms of Pakistan. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 7, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtaruddin, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.; Yao, L. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in corporate annual reports of Malaysian listed firms. J. Appl. Manag. Account. Res. 2009, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Z.; Kouser, R.; Ali, W.; Ahmad, Z.; Salman, T. Does corporate governance affect sustainability disclosure? A mixed methods study. Sustainability 2018, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.T.H.; Akter, A.; Li, X. Corporate governance and corporate social disclosures: A meta-analytical review. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2017, 25, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurghis, R. Integrated reporting and Board features. Audit Financ. 2017, 15, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiliç, M.; Kuzey, C.; Uyar, A. The impact of ownership and board structure on corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting in the Turkish banking industry. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2015, 15, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Kilic, M.; Nizamettin, B. Association between firm characteristics and corporate voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Turkish listed companies. Intang. Cap. 2014, 9, 1080–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.H.; Hanefah, M.M. Board diversity and corporate social responsibility in Jordan. J. Financ. Report. Account. 2016, 14, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid Lone, E.; Ali, A.; Khan, I. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: Evidence from Pakistan. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarasen, S.D.D.; Je-Yen, T.; Rajangam, N. Board composition and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 16, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, R.M.; Cooke, T.E. Culture, corporate governance and disclosure in Malaysian corporations. Abacus 2002, 38, 317–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, C.H.; Wan, T.W.D. Board Structure, Board Process and Board Performance: A Review & Research Agenda. J. Comp. Int. Manag. 2001, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, T.C.; Sultana, N. Corporate social responsibility: What motivates management to disclose. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlopoulos, A.; Magnis, C.; Iatridis, G.E. Integrated reporting: An accounting disclosure tool for high quality financial reporting. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 49, 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Loh, L. Board governance and sustainability disclosure: A cross-sectional study of Singapore-listed companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Aziz, T.; Saleem, S. The effect of corporate governance elements on corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure: An empirical evidence from listed companies at KSE Pakistan. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2015, 3, 530–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G. Corporate governance and financial characteristic effects on the extent of corporate social responsibility disclosure. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 10, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyduch, J.; Krasodomska, J. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An empirical study of Polish listed companies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, D.A. Audit committee performance: An investigation of the consequences associated with audit committees. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 1996, 15, 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S.S.; Wong, K.S. A study of corporate disclosure practice and effectiveness in Hong Kong. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2001, 12, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, L.J.; Parker, S.; Peters, G.F.; Raghunandan, K. The association between audit committee characteristics and audit fees. Audit. A J. Pract. Theory 2003, 22, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forker, J.J. Corporate governance and disclosure quality. Account. Bus. Res. 1992, 22, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariri, A.; Januarti, I. Audit Committee Characteristics and Integrated Reporting: Empirical Study of Companies Listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Eur. Res. Stud. 2017, 20, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, D.A.; Raghunandan, K. Enhancing audit committee effectiveness. J. Account. 1996, 182, 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hadi, A.; Hasan, M.M.; Habib, A. Risk committee, firm life cycle, and market risk disclosures. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2016, 24, 145–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, N.B.; Hutchinson, M. Corporate governance and risk management: The role of risk management and compensation committees. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2013, 9, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, N.; McManus, L.; Zhang, J. Corporate governance, firm characteristics and risk management committee formation in Australian companies. Manag. Audit. J. 2009, 24, 316–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byard, D.; Li, Y.; Weintrop, J. Corporate governance and the quality of financial analysts’ information. J. Account. Public Policy 2006, 25, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majiyebo, O.J.; Okpanachi, J.; Nyor, T.; Yahaya, O.A.; Mohammed, A. Audit committee independence, size and financial reporting quality of listed Deposit Money Banks in Nigeria. IOSR J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 20, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Rowbottom, N.; Locke, J. The emergence of <IR>. Account. Bus. Res. 2016, 46, 83–115. [Google Scholar]

- De Villiers, C.; Hsiao, P.C.K. Integrated Reporting. In Sustainability Accounting and Integrated Reporting; de Villiers, C., Maroun, W., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, WA, USA, 2018; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi, C.; Stark, A.W. Environmental, social and governance disclosure, integrated reporting, and the accuracy of analyst forecasts. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, C.; O’Dwyer, B.; Unerman, J. The Rise of Integrated Reporting: Understanding Attempts to Institutionalize a New Reporting Framework 2014, Seminar at University of Bergamo. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/67d4/e5f37c575006092baeb57b1c349373f99964.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Integrated Reporting <IR>. Available online: https://integratedreporting.org/ (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Ahmed Haji, A.; Anifowose, M. The trend of integrated reporting practice in South Africa: Ceremonial or substantive. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 190–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Tools for measuring quality improvement. Manag. Educ. 1996, 10, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M. Does designing environmental sustainability disclosure quality measures make a difference? Bus. Strategy Environ. 2019, 28, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H. Does size matter? Evaluating corporate environmental disclosure in the Australian mining and metal industry: A combined approach of quantity and quality measurement. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Li, Y.; Richardson, G.D.; Vasvari, F.P. Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Account. Organ. Soc. 2008, 33, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management: A stakeholder perspective. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, S.B.; Anderson, A.; Golden, S. Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance. J. Account. Public Policy 2001, 20, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonas, G.J.; Blanchet, J. Assessing quality of financial reporting. Account. Horiz. 2000, 14, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmar, M.; Abu Alia, M.; Ali, F.H. The Impact of Corporate Governance Mechanisms on Disclosure Quality: Evidence from Companies Listed in The Palestine Exchange. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2018, 4, 401–417. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, G.; van Beest, F. A Conceptually-Based Empirical Analysis on Quality Differences between UK Annual Reports and US 10-K Reports. J. Mod. Account. Audit. 2013, 9, 1281–1301. [Google Scholar]

- International Accounting Standard Board (IASB). Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. 2018. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/conceptual-framework/ (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Global Reporting Initiative. GRI 101: Foundation. 2016. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/gri-101-foundation/ (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Assurance on IR. Overview Feedback and Call to Action. 2014. Available online: http://integratedreporting.org/ (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- EY. EY’s Excellence in Integrated Reporting Awards. 2016. Available online: https://www.ey.com/Publication/vwLUAssets/ey-excellence-integrated-reporting-awards-2016/$FILE/ey-excellence-integrated-reporting-awards-2016.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2018).

- Churet, C.; Eccles, R.G. Integrated reporting, quality of management, and financial performance. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2014, 26, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Agency theory: An assessment and review. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. Organization theory and methodology. Account. Rev. 1983, 56, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, A.A.; Means, G.C. The Modern Corporation and Private Property; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Raviv, A. Some results on incentive con- tracts with application to education and employment, health insurance, and law enforcement. Am. Econ. Rev. 1978, 68, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maskati, M.; Hamdan, A. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure: Evidence from Bahrain. Int. J. Econ. Account. 2017, 8, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaziz, M.Z. Corporate governance and voluntary financial disclosure by Canadian listed firms. Manag. Rev. Int. J. 2014, 9, 44–69. [Google Scholar]

- Florackis, C.; Ozkan, A. Agency costs and corporate governance mechanisms: Evidence for UK firms. Int. J. Manag. Financ. 2008, 4, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, D.A.; Simkins, B.J.; Simpson, W.G. Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financ. Rev. 2003, 38, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathala, C.T.; Rao, R.P. The determinants of board composition: An agency theory perspective. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1995, 16, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Jaggi, B. Association between independent non-executive directors, family control and financial disclosures in Hong Kong. J. Account. Public Policy 2000, 19, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Sajid, M.; Razzaq, N.; Afzal, F. Agency Cost, Corporate Governance and Ownership Structure (The case of Pakistan). Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, A.J.; Dalziel, T. Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.Z.; Talha, M.; Mohamed, J.; Sallehhuddin, A. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and corporate governance in Malaysia. Int. J. Behav. Account. Financ. 2008, 1, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakanda, M.M.; Salim, B.; Chandren, S. Corporate governance reform and risk management disclosures: Evidence from Nigeria. Bus. Econ. Horiz. 2017, 13, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Chaarani, H. The impact of corporate governance on the performance of Lebanese banks. Int. J. Bus. Financ. Res. 2014, 8, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A. Corporate Governance and Agency Conflicts. J. Account. Res. 2008, 46, 1143–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokman, N.; Mula, J.M.; Cotter, J. Importance of Corporate Governance Quality and Voluntary Disclosures of Corporate Governance Information in Listed Malaysian Controlled Businesses. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Policy 2014, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.P.; Chen, H.J. Corporate governance and firm value as determinants of CEO compensation in Taiwan: 2SLS for panel data model. Manag. Res. Rev. 2011, 34, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, K.; Dahawy, K.; Abdel-Meguid, A.; Abdallah, S. Propensity and comprehensiveness of corporate internet reporting in Egypt: Do board composition and ownership structure matter. Int. J. Account. Inf. Manag. 2012, 20, 142–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.; Palepu, K. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfaya, A.; Whittington, M.; Alawattage, C. Exploring the quality of corporate environmental reporting: Surveying preparers’ and users’ perceptions. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 163–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemler, S.E.; Tsai, J. Best Practices in Interrater Reliability: Three Common Approaches. In Best Practices in Quantitative Methods; Osborne, J.W., Ed.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis an Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chakroun, R.; Hussainey, K. Disclosure quality in Tunisian annual reports. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2014, 11, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahboub, R. Main Determinants of Financial Reporting Quality in the Lebanese Banking Sector. Eur. Res. Stud. 2017, 20, 706–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hsiao, C. Analysis of Panel Data; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sayrs, L.W. Pooled Time Series Analysis; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification tests in econometrics. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Arrubla, Y.A.; Zorio-Grima, A.; García-Benau, M.A. Integrated reports: Disclosure level and explanatory factors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, N.; Alahakoon, Y. Environmental management accounting practices and their diffusion: The Sri Lankan experience. NSBM J. Manag. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACCA. Insights into Integrated Reporting 3.0: The Drive for Authenticity. 2019. Available online: https://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/ACCA_Global/professional-insights/IR-3/pi-insights-IR-3.0.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- De Villiers, C.; Naiker, V.; van Staden, C.J. The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1636–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka. Directions, Determinations, and Circulars issued to Licensed Specialized Banks 2013. Available online: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/directions (accessed on 19 October 2018).

- Moolman, J.; Oberholzer, M.; Steyn, M. The effect of integrated reporting on integrated thinking between risk, opportunity and strategy and the disclosure of risks and opportunities. South. Afr. Bus. Rev. 2016, 20, 600–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Manes-Rossi, F.; Nicolo, G.; Orelli, R.L. Reshaping Risk Disclosure through Integrated Reporting: Evidence from Italian Early Adopters. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 12, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; McNulty, T.; Stiles, P. Beyond agency conceptions of the work of the non-executive director: Creating accountability in the boardroom. Br. J. Manag. 2005, 16, S5–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, R.M. How effective are ‘Independent Directors’ in Sri Lanka. In Sunday Times 2015. Available online: http://www.sundaytimes.lk/150712/business-times/how-effective-are-independent-directors-in-sri-lanka-156153.html (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Ahmed Haji, A. The role of audit committee attributes in intellectual capital disclosures: Evidence from Malaysia. Manag. Audit. J. 2015, 30, 756–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, D.; Tilt, C.; Xydias-Lobo, M. Sustainability reporting by public listed companies in Sri Lanka. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Neill, M.S.; Schauster, E. Paid, earned, shared and owned media from the perspective of advertising and public relations agencies: Comparing China and the United States. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2018, 12, 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senaratne, S.; Gunarathne, A.D.N. Excellence Perspective for Management Education from a Global Accountants’ hub in Asia. In Management Education for Global Leadership; Baporikar, N., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 158–180. [Google Scholar]

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Materiality Background Paper for <IR> 2013. Available online: https://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/IR-Background-Paper-Materiality.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Gelmini, L.; Bavagnoli, F.; Comoli, M.; Riva, P. An Open Question in the Integrated Reporting: Materiality or Conciseness. In Proceedings of the CSEAR Conference, Padova, Italy, 18 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Connectivity Background Paper for <IR> 2013. Available online: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/IR-Background-Paper-Connectivity.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Hubbard, G. Measuring organizational performance: Beyond the triple bottom line. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Capitals Background Paper for <IR> 2013. Available online: https://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/IR-Background-Paper-Capitals.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Value Creation Background Paper for <IR> 2013. Available online: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Background-Paper-Value-Creation.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Marrison, C. The Fundamentals of Risk Measurement; McGraw Hill Professional: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maines, L.; Wahlen, J. The Nature of Accounting Information Reliability: Inferences from Archival and Experimental Research. Account. Horiz. 2006, 20, 399–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, Z. High-quality financial reporting: The six-legged stool. Strateg. Financ. 2003, 84, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, G.L.; Turner, J.L.; Coram, P.J.; Mock, T.J. Perceptions and misperceptions regarding the unqualified auditor’s report by financial statement preparers, users, and auditors. Account. Horiz. 2011, 25, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Companies Act, No. 07 of 2007. The Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka. Available online: http://www.drc.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Act-7-of-2007-English.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2018).

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Business Model Background Paper for <IR> 2013. Available online: https://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Business_Model.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Basis for Conclusions. 2013. Available online: http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/13-12-08-Basis-for-conclusions-IR.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2018).

- Schipper, K.; Vincent, L. Earnings quality. Account. Horiz. 2003, 17, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, V.; Branson, J.; Breesch, D. How to measure the comparability of financial statements. Int. J. Manag. Financ. Account. 2009, 1, 379–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuselinck, C.; Manigart, S. Financial reporting quality in private equity backed companies: The impact of ownership concentration. Small Bus. Econ. 2007, 29, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, S. The relationship between firm investment and financial status. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 673–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEC. Directive: Incorporation of Enforcement Procedures to Be Implemented on Listing Public Companies Violating Listing Requirements of the Colombo Stock Exchange. 2017. Available online: http://www.sec.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/directive3.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2018).

| Author(s) | Objective of the Paper | Assessment of Reporting Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Said et al. [18] | To examine the relationship between corporate governance characteristics and the extent of corporate social responsibility disclosure. | Using a corporate social responsibility disclosure index. |

| Chalaki et al. [19] | To investigate the effect of corporate governance attributes on financial reporting quality in firms listed in the Tehran Stock Exchange. | Based on two models (McNichols (2002) model and Collins and Kothari (1989) model). |

| Sharif and Rashid [20] | To explore the relationship between corporate governance elements and corporate social responsibility reporting disclosures in Pakistani listed commercial banks. | Using a corporate social responsibility reporting index. |

| Hidalgo et al. [21] | To analyze the impact of the board of directors and ownership structure on the voluntary disclosure of intangibles. | Using an information disclosure index (structural capital, human capital and relational capital). |

| Rodrigues et al. [22] | To examine the association between corporate governance and intellectual capital reporting in a period of financial crisis in Portugal. | Using an intellectual capital disclosure index. |

| Iatridis [23] | To investigates the relationship between environmental disclosure quality and corporate governance. | Based on an environmental disclosure index. |

| Rao et al. [24] | To investigate the relationship between environmental reporting and the corporate governance attributes of companies in Australia. | Based on the total number of words dedicated to environmental issues in the annual report. |

| Amran et al. [25] | To examine the role of the board of directors in sustainability reporting quality in the Asia-Pacific region. | Based on a scoring model modified from the environmental disclosure index developed by Clarkson et al. (2008) and Sutantoputra (2009). |

| Michelon and Parbonetti [26] | To examine the impact of board composition, leadership and structure on sustainability disclosure. | Based on a sustainability disclosure index. |

| Governance Aspect | Measurement Criteria | Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Board size | The number of board members. | [43,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Independence of board | The percentage of independent non-executive directors to the total number of board members. | [43,47,48,49,51,52,53] |

| Composition of board | The proportion of non-executive directors to the total number of directors. | [54,55] |

| CEO duality | A dummy variable equal to one when the same person serves as a CEO as well as the chairman, and zero otherwise. | [14,47,48,53,54,56,57,58] |

| Gender of CEO | A dummy variable equal to one when the gender of CEO is male, and zero if the gender is female. | [48] |

| Gender diversity | The percentage of women in the board/number of female directors on board. | [24,25,47,48,49,51,59,60,61] |

| Presence of an audit committee | A dummy variable equal to one when there is an audit committee available, and zero otherwise. | [62,63] |

| Independence of the audit committee | The percentages of non-executive directors to total of directors sitting on audit committee. The percentages of non-executive directors sitting on audit committee to the total of directors. The number of directors (audit committee members) from outside. | [14,18,57,64,65,66] |

| Effectiveness of the audit committee | The number of meetings conducted per year. | [67] |

| Presence of a nomination committee | A dummy variable equal to one when there is a nomination committee available, and zero otherwise. | [14] |

| Composition of the nomination committee | The percentage of independent directors on the nomination committee as stipulated by the company. The percentage of non-executive board members on the nomination committee. | [14,57] |

| Presence of a separate risk management committee | A dummy variable equal to one when a company has a separate risk management committee, and zero otherwise. | [68,69,70] |

| Presence of a corporate governance committee | A dummy variable equal to one when there is a corporate governance committee available, and zero otherwise. | [14] |

| Corporate Governance Characteristics | Reporting Quality | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Relationship | Negative Relationship | |

| Board size | [43,45,47,49,50] | [71] |

| Independence of board | [43,47,51,52] | [49,53] |

| CEO duality | [14,54] | [47,53,56,58] |

| Gender diversity | [24,25,47,51,60,61] | [49,59] |

| Independence of the audit committee | [14,18,65] | [66,72] |

| Presence of a separate risk management committee | [68,69,70] | - |

| Variable | Symbol | Measurement | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | |||

| Board size | BS | The number of board members. | [43,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Independence of board | IB | The percentage of independent non-executive directors on the board. | [43,47,48,49,51,52,53] |

| CEO duality | CD | A dummy variable equal to one when the same person serves as a CEO as well as the chairman, and zero otherwise. | [14,47,48,53,54,56,57,58] |

| Gender diversity | GD | The percentage of women on the board. | [24,25,47,48,49,51,59,60,61] |

| Composition of the audit committee | AC | The percentage of independent non-executive directors on the audit committee. | [14,18,57,64,65,66] |

| The presence of a separate risk management committee | RC | A dummy variable equal to one when a company has a separate risk management committee, and zero otherwise. | [68,69,70] |

| Dependent variable | |||

| Quality of IR | IRQ | Developed index (See the description below) | |

| Control variables | |||

| Company size | CS | Natural logarithm of total assets. | [59,117,118] |

| Profitability | PF | Return on equity = Net profit after tax/total equity. | [59,112] |

| Industry | n | Mean | Median | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banking and finance | 54 | 70.26 | 70.50 | 8.40 | 52 | 89 |

| Insurance | 15 | 68.47 | 72 | 8.28 | 56 | 78 |

| Plantation, food and beverage | 15 | 71.33 | 72 | 5.21 | 64 | 79 |

| Engineering, power and energy | 9 | 62.56 | 65 | 7.94 | 51 | 71 |

| Diversified holdings | 15 | 70.27 | 68 | 6.79 | 64 | 88 |

| Manufacturing, footwear, textiles and motors | 9 | 78.67 | 78 | 15.03 | 57 | 101 |

| Services | 15 | 70.67 | 71 | 4.89 | 61 | 77 |

| Variables † | n | Mean | Median | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 132 | 70.273 | 70.000 | 8.565 | 51.000 | 101.000 | |

| 132 | 9.402 | 9.000 | 1.815 | 5.000 | 13.000 | |

| 132 | 0.454 | 0.429 | 0.142 | 0.167 | 0.800 | |

| 132 | 0.083 | 0.000 | 0.277 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| 132 | 0.101 | 0.095 | 0.100 | 0.000 | 0.375 | |

| 132 | 0.840 | 1.000 | 0.185 | 0.333 | 1.500 | |

| 132 | 0.432 | 0.000 | 0.497 | 0.000 | 1.000 | |

| 132 | 23.869 | 23.701 | 2.016 | 15.983 | 27.765 | |

| 132 | 0.122 | 0.107 | 0.083 | 0.014 | 0.277 |

| Variables † | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.263 ** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 3 | 0.088 | −0.221 * | 1.000 | |||||||

| 4 | 0.144 | 0.119 | 0.039 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 5 | 0.022 | 0.126 | 0.284 ** | −0.165 | 1.000 | |||||

| 6 | 0.163 | 0.061 | 0.067 | 0.187 * | −0.223 * | 1.000 | ||||

| 7 | 0.246 ** | 0.119 | 0.397 ** | 0.069 | 0.362 ** | −0.153 | 1.000 | |||

| 8 | 0.124 | 0.248** | 0.358 ** | 0.013 | 0.304 ** | −0.045 | 0.541 ** | 1.000 | ||

| 9 | 0.133 | −0.144 | 0.167 | −0.091 | 0.137 | −0.039 | 0.445 ** | 0.019 | 1.000 | |

| Variables † | Coefficients | Z |

|---|---|---|

| 0.705 * | 2.410 | |

| −1.097 | −0.260 | |

| 1.238 | 0.460 | |

| 3.002 | 0.630 | |

| 3.294 | 1.380 | |

| 4.404 ** | 2.620 | |

| −0.311 | −1.240 | |

| −10.493 | −1.770 | |

| R2 | 0.1145 | |

| Prob > X2 | 0.0344 | |

| Wald chi2 | 16.6100 | |

| n | 132 |

| Hypothesis | Panel Regression Results | Studies with Similar Findings | Studies with Contradictory Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 = There is a significant positive relationship between board size and IRQ. | Accepted | [43,45,46,47] | [49,50,71] |

| H2 = There is a significant positive relationship between the independence of the board and IRQ. | Rejected | [53] | [43,47,49,51,52] |

| H3 = There is a significant negative relationship between CEO duality and IRQ. | Rejected | [54] | [14,47,53,56,58] |

| H4 = There is a significant positive relationship between gender diversity and IRQ. | Rejected | [25,47,60,61] | [24,49,51,59] |

| H5 = There is a significant positive relationship between the percentages of independent non-executive directors on the audit committee and IRQ. | Rejected | [65] | [14,18,66,72] |

| H6 = There is a significant positive relationship between the presence of a separate risk management committee and IRQ. | Accepted | [68,69,70] | - |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cooray, T.; Gunarathne, A.D.N.; Senaratne, S. Does Corporate Governance Affect the Quality of Integrated Reporting? Sustainability 2020, 12, 4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104262

Cooray T, Gunarathne ADN, Senaratne S. Does Corporate Governance Affect the Quality of Integrated Reporting? Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104262

Chicago/Turabian StyleCooray, Thilini, A. D. Nuwan Gunarathne, and Samanthi Senaratne. 2020. "Does Corporate Governance Affect the Quality of Integrated Reporting?" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104262

APA StyleCooray, T., Gunarathne, A. D. N., & Senaratne, S. (2020). Does Corporate Governance Affect the Quality of Integrated Reporting? Sustainability, 12(10), 4262. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104262