Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Financial Performance: A New Insight

Abstract

1. Introduction

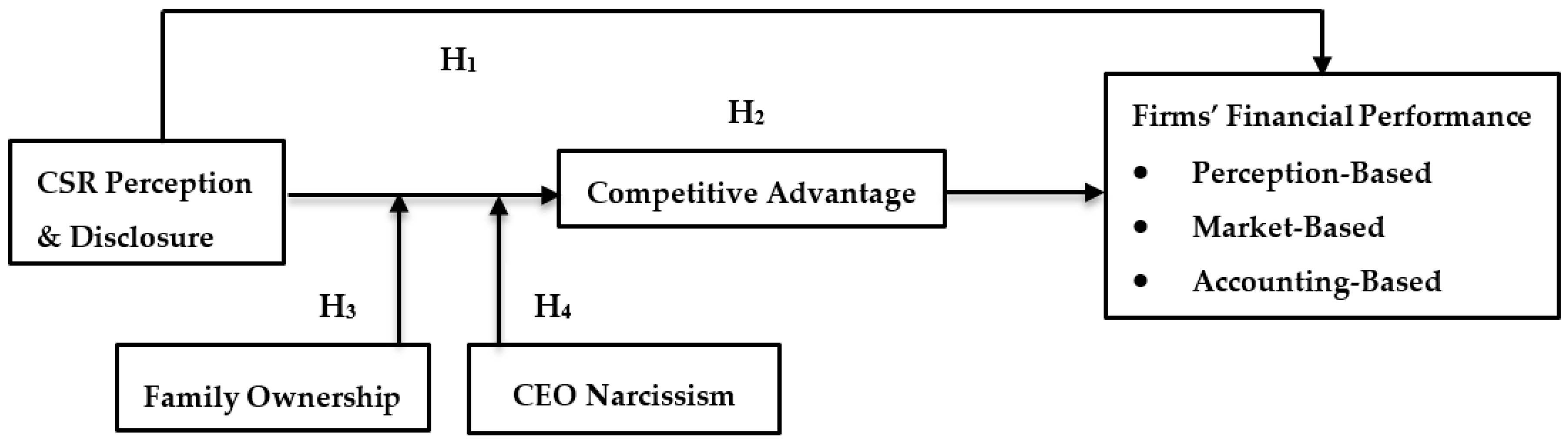

2. Literature Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Resource-Based View

2.2. CSR and Firms’ Financial Performance

2.3. Mediation of Competitive Advantage

2.4. Moderation of Ownership Structure

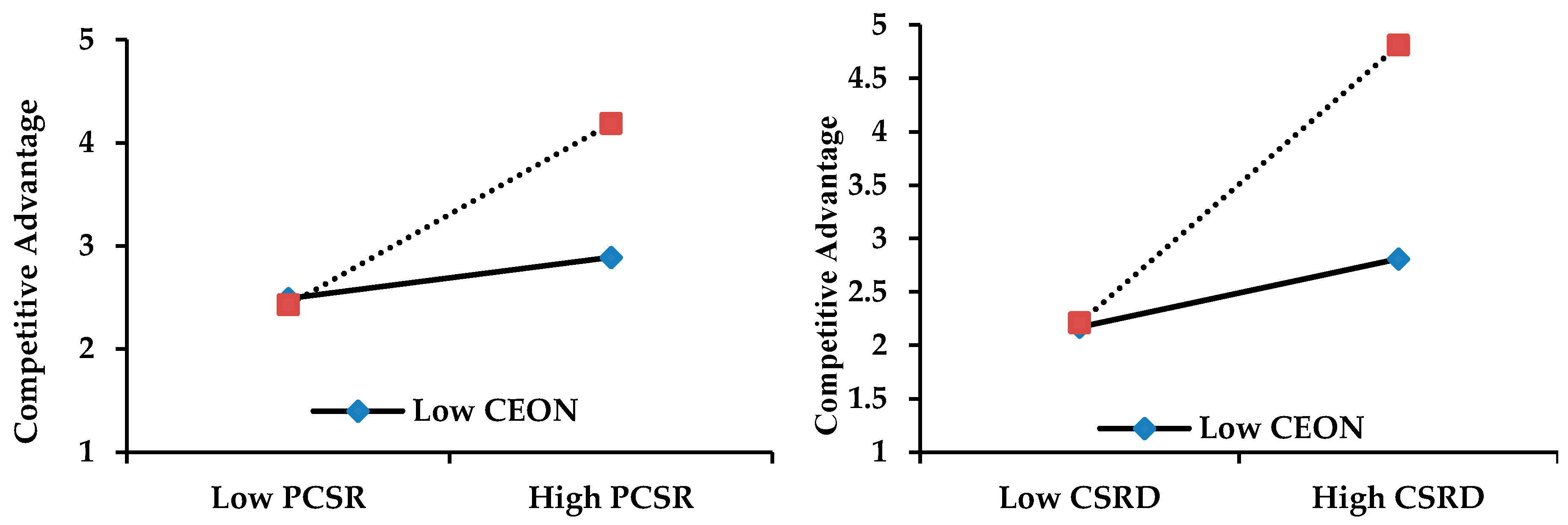

2.5. Moderation of CEO Narcissism

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Fu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Moore, J.H.; Wang, Z. Corporate social responsibility and employee outcomes: A moderated mediation model of organizational identification and moral identity. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashrafi, M.; Magnan, G.M.; Adams, M.; Walker, T.R. Understanding the Conceptual Evolutionary Path and Theoretical Underpinnings of Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability. Sustainability 2020, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Jia, Y.; Meng, X.; Li, C. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and financial performance: The moderating effect of the institutional environment in two transition economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 150, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beurden, P.; Gössling, T. The worth of values–a literature review on the relation between corporate social and financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics. 2008, 82, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Qadeer, F.; Abbas, Z.; Hussain, I.; Saleem, M.; Hussain, A.; Aman, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employees’ Negative Behaviors under Abusive Supervision: A Multilevel Insight. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Mahmood, S.; Ali, H.; Ali Raza, M.; Ali, G.; Aman, J.; Bano, S.; Nurunnabi, M. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices and Environmental Factors through a Moderating Role of Social Media Marketing on Sustainable Performance of Business Firms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.; de las Heras-Rosas, C. Corporate social responsibility and human resource management: Towards sustainable business organizations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Berens, G. The impact of four types of corporate social performance on reputation and financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics. 2015, 131, 337–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, S.A.; Lefen, L. An analysis of corporate social responsibility and firm performance with moderating effects of CEO power and ownership structure: A case study of the manufacturing sector of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I.; Ashraf, S.; Sarfraz, M. The organizational identification perspective of CSR on creative performance: The moderating role of creative self-efficacy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Thai, V.V. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction, relationship maintenance and loyalty in the shipping industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 22, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strateg. Manag. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpp, C.; Guenther, T. Too little or too much? Exploring U-shaped relationships between corporate environmental performance and corporate financial performance. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.Y.; Danish, R.Q.; Asrar-ul-Haq, M. How corporate social responsibility boosts firm financial performance: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewatsch, S.; Kleindienst, I. When does it pay to be good? Moderators and mediators in the corporate sustainability–corporate financial performance relationship: A critical review. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 145, 383–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Dou, J.; Jia, S. A meta-analytic review of corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance: The moderating effect of contextual factors. Bus. Soc. 2016, 55, 1083–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. The resource-based theory of the firm. Organ. Sci. 1996, 7, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S.; Wright, P.M. Corporate social responsibility: Strategic implications. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, M.C.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics. 2006, 69, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, F.; Rehman, I.U.; Nawaz, F.; Nawab, N. Does family control explain why corporate social responsibility affects investment efficiency? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H. Organizational responsibility: Doing good and doing well. APA Handb. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2011, 3, 855–879. [Google Scholar]

- Anser, M.K.; Zhang, Z.; Kanwal, L. Moderating effect of innovation on corporate social responsibility and firm performance in realm of sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Yang, H.-L.; Liou, D.-Y. The impact of corporate social responsibility on financial performance: Evidence from business in Taiwan. Technol. Soc. 2009, 31, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, P.; Cupertino, S. CSR strategic approach, financial resources and corporate social performance: The mediating effect of innovation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chau, K.; Wang, H.; Pan, W. A decade’s debate on the nexus between corporate social and corporate financial performance: A critical review of empirical studies 2002–2011. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-H. The influence of corporate environmental ethics on competitive advantage: The mediation role of green innovation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2011, 104, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantele, S.; Zardini, A. Is sustainability a competitive advantage for small businesses? An empirical analysis of possible mediators in the sustainability–financial performance relationship. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.-H.; Kim, M.; Qian, C. Effects of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance: A competitive-action perspective. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 1097–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D.S. Creating and capturing value: Strategic corporate social responsibility, resource-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1480–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhou, Y.; Singal, M.; Koh, Y. CSR and financial performance: The role of CSR awareness in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 57, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Martín, P.J.; Rubio, A. Doing good and different! The mediation effect of innovation and investment on the influence of CSR on competitiveness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, L.; Rubio, A.; de Maya, S.R. Competitiveness as a strategic outcome of corporate social responsibility. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, M. Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family-controlled firms. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2005, 29, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Wagner, M. The effect of family ownership on different dimensions of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from large US firms. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 23, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, T.M.; Nason, R.S.; Nordqvist, M.; Brush, C.G. Why do family firms strive for nonfinancial goals? An organizational identity perspective. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2013, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Hoffman, B.J.; Campbell, S.M.; Marchisio, G. Narcissism in organizational contexts. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Mack, D.Z.; Chen, G. The differential effects of CEO narcissism and hubris on corporate social responsibility. Strateg. Manag. 2018, 39, 1370–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.V.; Aime, F.; Ridge, J.; Hill, A. Corporate social responsibility or CEO narcissism? CSR motivations and organizational performance. Strateg. Manag. 2016, 37, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Newman, A.; Shao, R.; Cooke, F.L. Advances in employee-focused micro-level research on corporate social responsibility: Situating new contributions within the current state of the literature. J. Bus. Ethics. 2019, 157, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, A.; Qadeer, F.; Shahzadi, G.; Jia, F. Getting paid to be good: How and when employees respond to corporate social responsibility? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Suar, D. Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? J. Bus. Ethics. 2010, 95, 571–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O. Antecedents and benefits of corporate citizenship: An investigation of French businesses. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 51, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Muttakin, M.B.; Siddiqui, J. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from an emerging economy. J. Bus. Ethics. 2013, 114, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, S.; Caporin, M.; Fontini, F. A multidimensional analysis of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and firms’ economic performance. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 147, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, M.; Joshi, M.; Batra, G.S. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from India. Adv. Account. 2014, 30, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, K.F.; Thai, V.V.; Wong, Y.D.; Wang, X. Interaction impacts of corporate social responsibility and service quality on shipping firms’ performance. Transport. Res. A-Pol. 2018, 113, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.S.; Kanwal, L. Impact of corporate social responsibility disclosure on financial performance: Case study of listed pharmaceutical firms of Pakistan. J. Bus. Ethics. 2018, 150, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, B.M.; Lange, D.; Ashforth, B.E. Narcissistic organizational identification: Seeing oneself as central to the organization’s identity. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Meng, F.; He, Y.; Gu, Z. The influence of corporate social responsibility on competitive advantage with multiple mediations from social capital and dynamic capabilities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protogerou, A.; Caloghirou, Y.; Lioukas, S. Dynamic capabilities and their indirect impact on firm performance. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2012, 21, 615–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhou, Z. Research on the Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on the Persistence of Corporate Competitive Advantage. Forum Sci. Technol. China 2014, 5, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Lai, S.-B.; Wen, C.-T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics. 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, C.J.; Whitman, D.S.; Weingarden, S.M.; Hiller, N.J. The bright-side and the dark-side of CEO personality: Examining core self-evaluations, narcissism, transformational leadership, and strategic influence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, C.I.; Chen, Z. Beyond the individual victim: Multilevel consequences of abusive supervision in teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Zhang, Z.; Zyphur, M.J. Alternative methods for assessing mediation in multilevel data: The advantages of multilevel SEM. Struct. Equ. Model. 2011, 18, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R. Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1982, 67, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, L.R.; Demaree, R.G.; Wolf, G. rwg: An assessment of within-group interrater agreement. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.; Qadeer, F.; Mahmood, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Ethical Leadership and Employee Green Behavior: A Multilevel Moderated Mediation Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.; Kim, Y.; Han, K.; Jackson, S.E.; Ployhart, R.E. Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaefarian, G.; Kadile, V.; Henneberg, S.C.; Leischnig, A. Endogeneity bias in marketing research: Problem, causes and remedies. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 65, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooldridge, J.M. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach; Nelson Education: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T.; Fang, E.; Wang, F. Is neutral really neutral? The effects of neutral user-generated content on product sales. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surroca, J.; Tribó, J.A. Managerial entrenchment and corporate social performance. J. Bus. Finance. Account. 2008, 35, 748–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. Study on the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M. Corporate social responsibility, noise, and stock market volatility. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 238–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Barroso-Méndez, M.J.; Pajuelo-Moreno, M.L.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and performance: A meta-analytic approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akben-Selcuk, E. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The moderating role of ownership concentration in Turkey. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Cho, K.; Park, C.K. Does CSR Assurance Affect the Relationship between CSR Performance and Financial Performance? Sustainability 2019, 11, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allouche, J.; Laroche, P. A meta-analytical investigation of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Revue. Gestion. Res. Hum. 2005, 5, 8–41. [Google Scholar]

- Majeed, S. The impact of competitive advantage on organizational performance. Eur. J. Busi. Manag. 2011, 3, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Du, J.; Zhang, W. Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Innovation Sustainability: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Alpha | AVE | CR | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Financial Performance | 7 | 0.76 | 0.50 | 0.94 | 4.00 | 0.41 |

| Perceived CSR | 29 | 0.92 | 0.51 | 0.89 | 4.30 | 0.31 |

| Competitive Advantage | 8 | 0.71 | 0.61 | 0.79 | 4.10 | 0.57 |

| CEO Narcissism | 8 | 0.59 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 4.00 | 0.41 |

| Family Ownership | 2 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.20 |

| Tobin Q | 2.03 | 1.55 | ||||

| Earnings per Share | 34.01 | 18.0 | ||||

| Return on Equity | 25.09 | 40.1 | ||||

| CSR Disclosure | 0.71 | 0.12 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived FFP | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Perceived CSR | 0.11 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Competitive Advantage | 0.15 * | 0.25 * | 1 | ||||||

| 4. CEO Narcissism | 0.57 * | 0.11 | 0.05 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Family Ownership | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.30 ** | 0.08 | 1 | ||||

| 6. Tobin Q | 0.05 | 0.23 * | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 1 | |||

| 7. Earnings per Share | 0.06 | 0.17 * | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 1 | ||

| 8. Return on Equity | 0.07 | 0.20 ** | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.28 * | 0.43 * | 1 | |

| 9. CSR Disclosers | 0.21 * | 0.04 | 0.24 * | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.20 * | 1 |

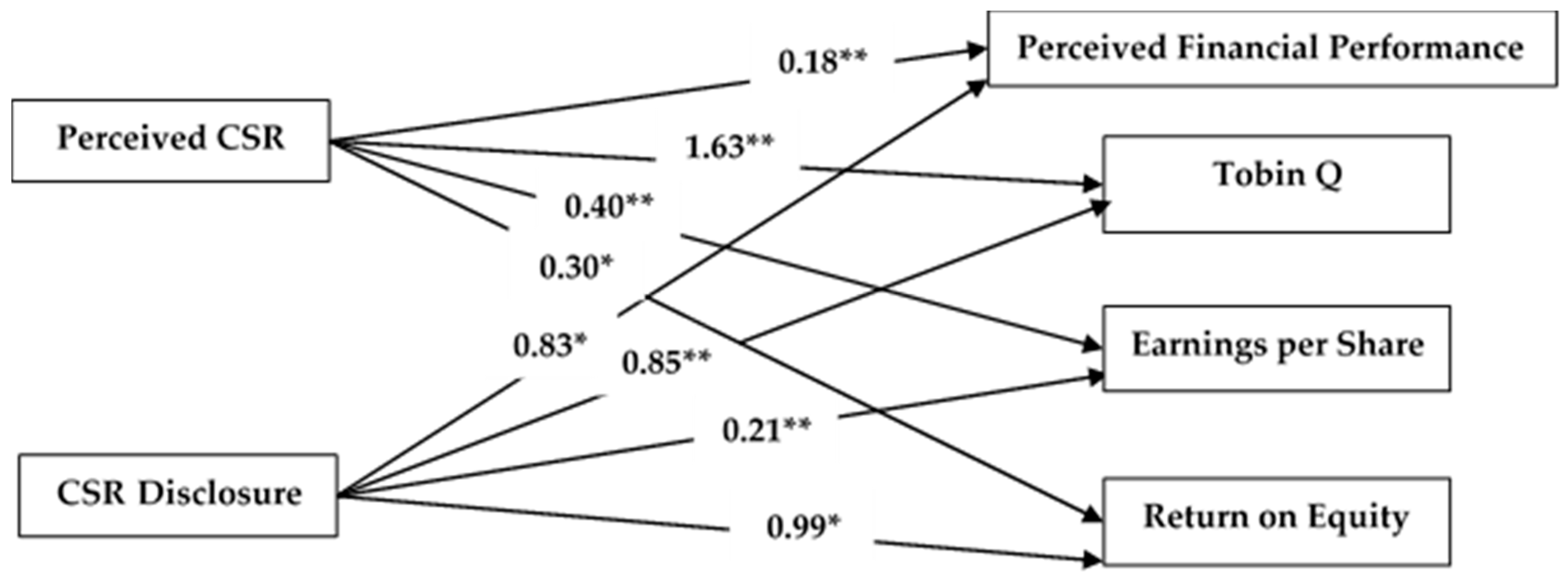

| Estimates | p-Value | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived CSR → Perceived Financial Performance | 0.18 ** | 0.05 | H1: Supported |

| Perceived CSR → Tobin Q | 1.63 ** | 0.03 | H1: Supported |

| Perceived CSR → Earning Per Share | 0.40 ** | 0.04 | H1: Supported |

| Perceived CSR → Return on Equity | 0.30 * | 0.03 | H1: Supported |

| CSR Disclosers → Perceived Financial Performance | 0.83 * | 0.02 | H1: Supported |

| CSR Disclosers → Tobin Q | 0.85 ** | 0.05 | H1: Supported |

| CSR Disclosers → Earning Per Share | 0.21 ** | 0.05 | H1: Supported |

| CSR Disclosers → Return on Equity | 0.99 * | 0.01 | H1: Supported |

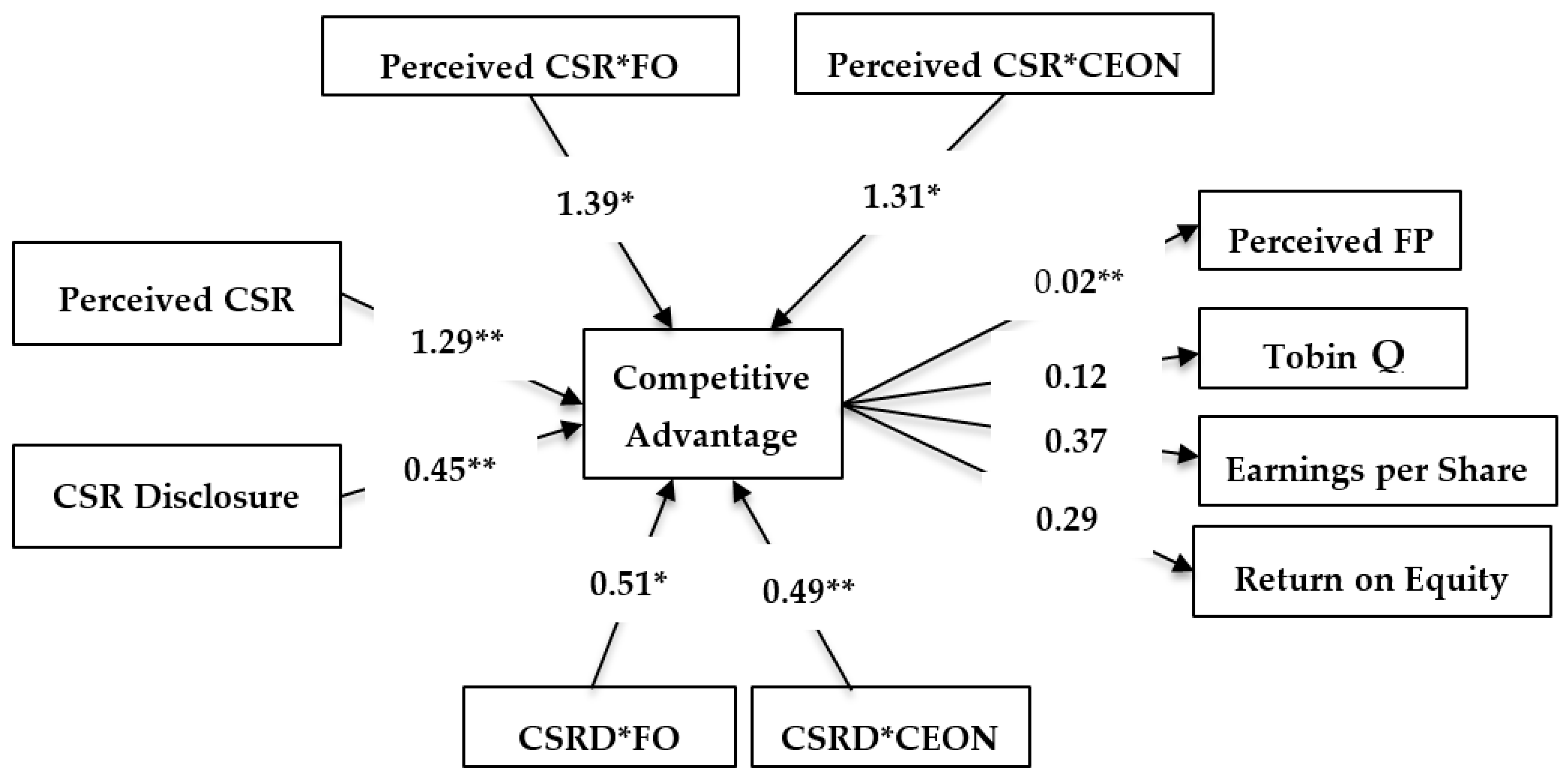

| Perceived CSR → Competitive Advantage | 1.29 * | 0.03 | |

| CSR Disclosers → Competitive Advantage | 0.45 ** | 0.05 | |

| Competitive Advantage → Perceived Financial Performance | 0.02 ** | 0.05 | |

| Competitive Advantage → Tobin Q | 0.12 | ns | |

| Competitive Advantage → Earning Per Share | 0.37 | Ns | |

| Competitive Advantage → Return on Equity | 0.29 | Ns |

| Estimates | 95% CI | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived CSR → CA → PFP | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.04] | ns |

| Perceived CSR → CA → Tobin Q | 0.15 * | [0.05, 0.19] | H2: Supported |

| Perceived CSR → CA → EPS | 0.48 * | [0.21, 0.77] | H2: Supported |

| Perceived CSR → CA → ROE | 0.37 * | [0.12, 0.55] | H2: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure → CA → PFP | 0.009 | [−0.11, 0.02] | ns |

| CSR Disclosure → CA → Tobin Q | 0.05 | [−0.16, 0.04] | ns |

| CSR Disclosure → CA → EPS | 0.17 ** | [0.22, 0.41] | H2: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure → CA → ROE | 0.13 ** | [0.03, 0.59] | H2: Supported |

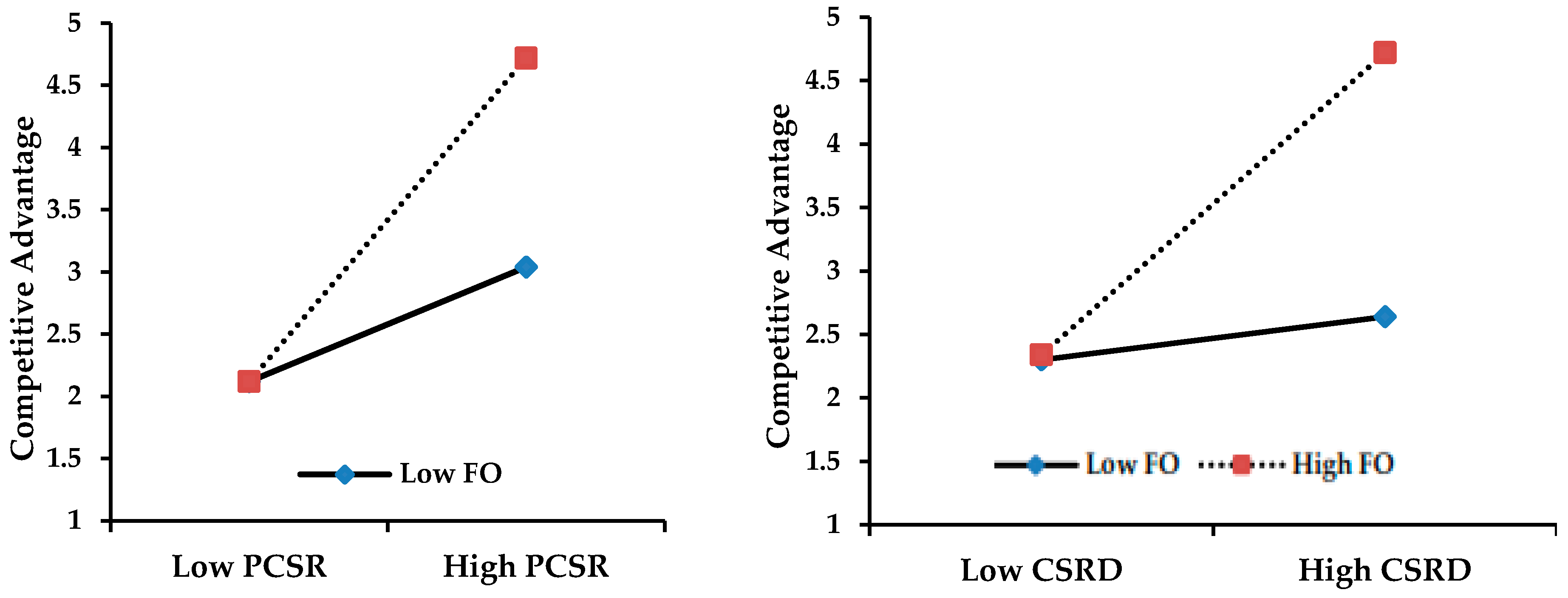

| Estimates | 95% CI | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived CSR*FO → CA | 1.39 * | [0.88, 2.99] | |

| CSR Disclosure *FO → CA | 0.51 * | [0.13, 0.68] | |

| Perceived CSR*FO → CA → PFP | 0.03 ** | [0.01, 0.05] | H3: Supported |

| Perceived CSR*FO → CA → Tobin Q | 0.17 * | [0.02, 0.21] | H3: Supported |

| Perceived CSR*FO → CA → EPS | 0.51 * | [0.14, 0.68] | H3: Supported |

| Perceived CSR*FO → CA → ROE | 0.40 * | [0.09, 0.11] | H3: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure *FO → CA → PFP | 0.01 | [−0.01, 0.03] | ns |

| CSR Disclosure*FO → CA → Tobin Q | 0.06 | [−0.14, 0.03] | ns |

| CSR Disclosure*FO → CA → EPS | 0.19 ** | [0.19, 0.32] | H3: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure*FO → CA → ROE | 0.15 ** | [0.01, 0.47] | H3: Supported |

| Estimates | 95% CI | Remarks | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived CSR*CEON → CA | 1.31 * | [0.91, 1.87] | |

| CSR Disclosure * CEON → CA | 0.49 ** | [0.03, 0.61] | |

| Perceived CSR* CEON → CA → PFP | 0.03 ** | [0.02, 0.09] | H4: Supported |

| Perceived CSR* CEON → CA → Tobin Q | 0.16 * | [0.15, 0.39] | H4: Supported |

| Perceived CSR* CEON → CA → EPS | 0.49 * | [0.11, 1.22] | H4: Supported |

| Perceived CSR* CEON → CA → ROE | 0.38 * | [0.19, 0.88] | H4: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure* CEON → CA → PFP | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.09] | ns |

| CSR Disclosure* CEON → CA → Tobin Q | 0.06 ** | [0.03, 0.10] | H4: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure* CEON → CA → EPS | 0.18 * | [0.06, 0.23] | H4: Supported |

| CSR Disclosure* CEON → CA → ROE | 0.14 * | [0.04, 0.29] | H4: Supported |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahmood, F.; Qadeer, F.; Sattar, U.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Saleem, M.; Aman, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Financial Performance: A New Insight. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104211

Mahmood F, Qadeer F, Sattar U, Ariza-Montes A, Saleem M, Aman J. Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Financial Performance: A New Insight. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104211

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmood, Faisal, Faisal Qadeer, Usman Sattar, Antonio Ariza-Montes, Maria Saleem, and Jaffar Aman. 2020. "Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Financial Performance: A New Insight" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104211

APA StyleMahmood, F., Qadeer, F., Sattar, U., Ariza-Montes, A., Saleem, M., & Aman, J. (2020). Corporate Social Responsibility and Firms’ Financial Performance: A New Insight. Sustainability, 12(10), 4211. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104211