Circular Economy Practices and Strategies in Public Sector Organizations: An Integrative Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

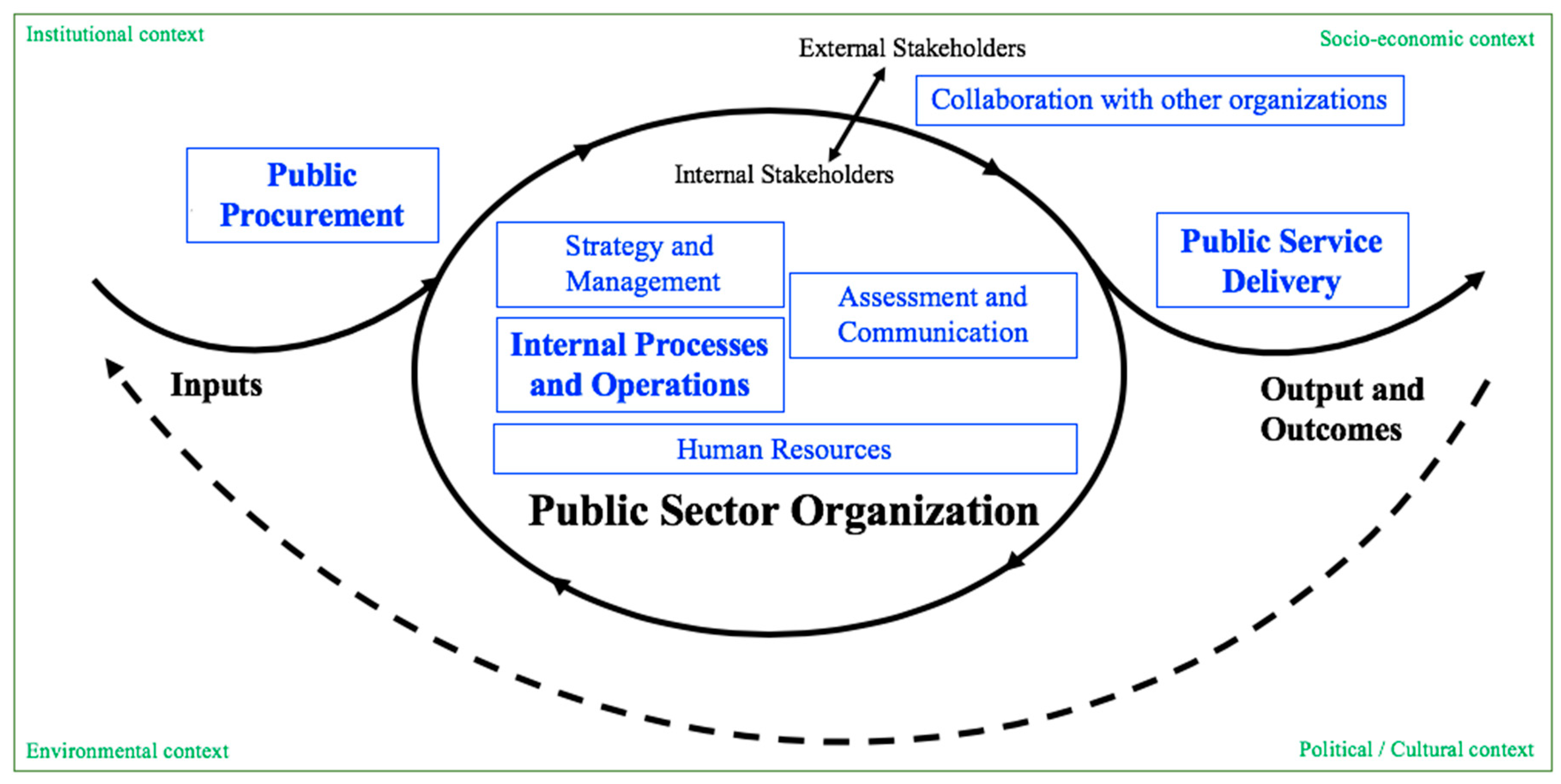

2. Organizational Sustainability Perspective of PSOs

The contributions of the organization to sustainability equilibria, including the economic, environmental, and social dimensions of today, as well as their interrelations within and throughout the time dimension (i.e., the short-, long-, and longer-term). This entails the continuous incorporation and integration of sustainability issues in the organization’s system elements (operations and production, strategy and management, governance, organizational systems, service provision, and assessment and reporting), as well as change processes and their rate of change.[30] (p. 16)

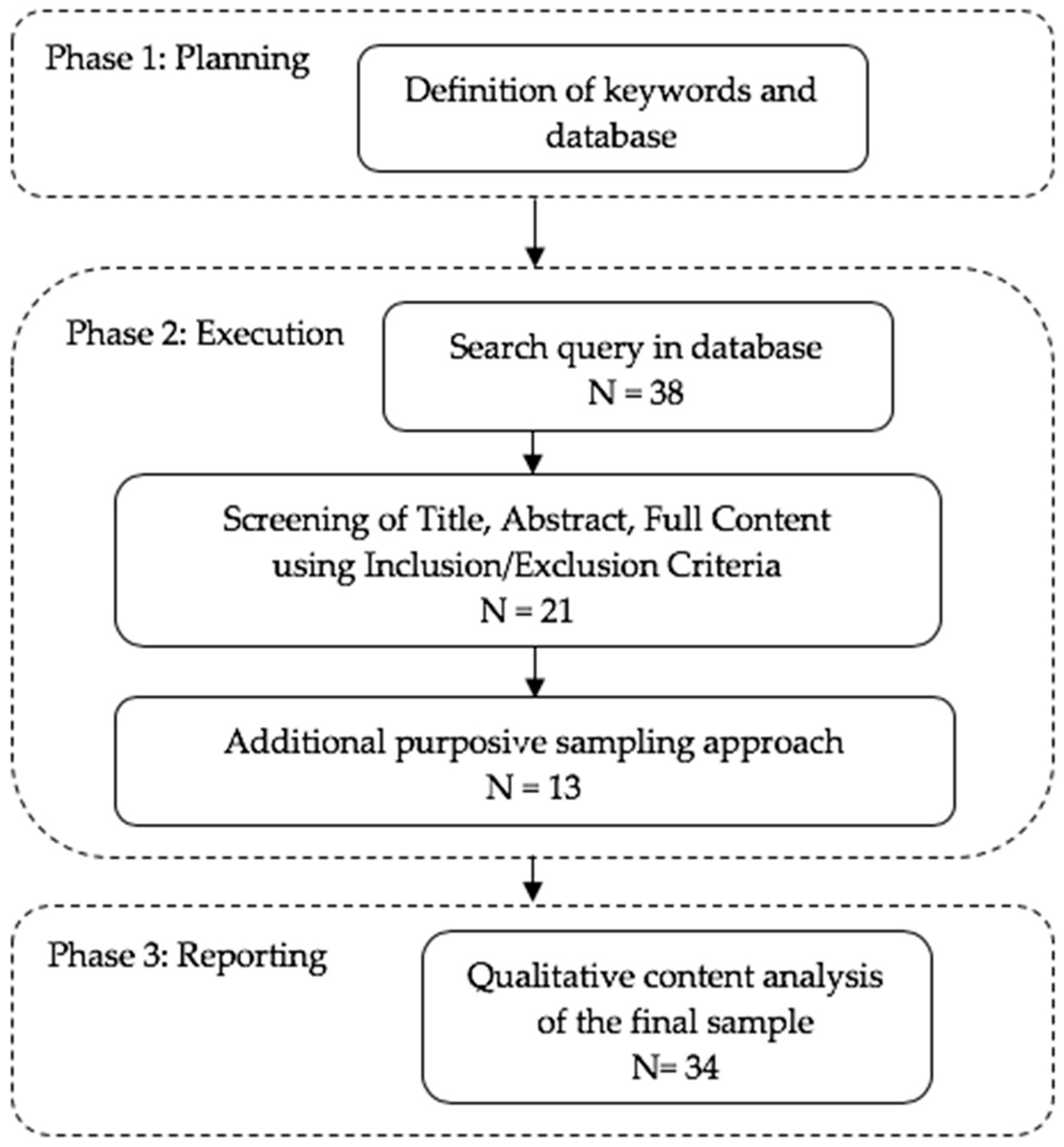

3. Methods

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Circular PP Practices

4.2. CE Practices and Strategies in Internal Processes and Operations

4.3. CE Practices and Strategies in Public Service Delivery

5. An Organizational CE Framework of PSOs

5.1. Public Procurement

5.2. Internal Processes and Operations

5.3. Public Service Delivery

5.4. Human Resources

5.5. Collaboration with Other Organizations

5.6. Strategy and Management

5.7. Assessment and Communication

5.8. Institutional, Environmental, Socioeconomic and Political Contexts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Esposito, M.; Tse, T.; Soufani, K. Introducing a Circular Economy: New Thinking with New Managerial and Policy Implications. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, D.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Godsell, J. Towards a more circular economy: Exploring the awareness, practices, and barriers from a focal firm perspective. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy – A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milios, L. Advancing to a Circular Economy: Three essential ingredients for a comprehensive policy mix. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 861–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its Limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowall, W.; Geng, Y.; Huang, B.; Barteková, E.; Bleischwitz, R.; Türkeli, S.; Kemp, R.; Doménech, T. Circular Economy Policies in China and Europe. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eurostat Government Expenditure by Function – COFOG. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Government_expenditure_by_function_–_COFOG (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Schwab, K. Insight Report - The Global Competitiveness Report 2019 - World Economic Forum; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Moving towards a Circular Economy with EMAS; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueiro, L.; Ramos, T.B. The integration of environmental practices and tools in the Portuguese local public administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reike, D.; Vermeulen, W.J.V.; Witjes, S. The circular economy: New or Refurbished as CE 3.0? — Exploring Controversies in the Conceptualization of the Circular Economy through a Focus on History and Resource Value Retention Options. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, I.; Domingues, A.R.; Caeiro, S.; Painho, M.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Videira, N.; Walker, R.M.; Huisingh, D.; Ramos, T.B. Sustainability policies and practices in public sector organisations: The case of the Portuguese Central Public Administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 616–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranängen, H.; Cöster, M.; Isaksson, R.; Garvare, R. From global goals and planetary boundaries to public governance-A framework for prioritizing organizational sustainability activities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ball, A.; Grubnic, S. Sustainability accounting and accountability in the public sector. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 176–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, T.B.; Alves, I.; Subtil, R.; Joanaz de Melo, J. Environmental performance policy indicators for the public sector: The case of the defence sector. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 82, 410–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggestam-Pontoppidan, B.C.; Andernack, I. Annex 2: Key Characteristics of Public Sector Entities. In Interpretation and Application of IPSAS; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 413–414. [Google Scholar]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Ritala, P.; Huotari, P. The Circular Economy: Exploring the Introduction of the Concept Among S&P 500 Firms. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R. Are companies planning their organisational changes for corporate sustainability? An analysis of three case studies on resistance to change and their strategies to overcome it. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Buren, N.; Demmers, M.; van der Heijden, R.; Witlox, F. Towards a circular economy: The role of Dutch logistics industries and governments. Sustainability 2016, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Sharmina, M.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Heyes, G.; Azapagic, A. Integrating Backcasting and Eco-Design for the Circular Economy: The BECE Framework. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 526–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- BSI. Executive Briefing: BS 8001 – A Guide; BSI Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- EMF. Delivering the Circular Economy: A Toolkit for Policymakers; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: Cowes, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, K.; Lynch, N. Diversifying and de-growing the circular economy: Radical social transformation in a resource-scarce world. Futures 2016, 82, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, V.; Sahakian, M.; van Griethuysen, P.; Vuille, F. Coming Full Circle: Why Social and Institutional Dimensions Matter for the Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sarkis, J.; Lopes de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.; Scott Renwick, D.W.; Singh, S.K.; Grebinevych, O.; Kruglianskas, I.; Filho, M.G. Who is in charge? A review and a research agenda on the ‘human side’ of the circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Seifert, C.; Krannich, T.; Guenther, E. Gearing up sustainability thinking and reducing the bystander effect – A case study of wastewater treatment plants. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Fan, C.; Shi, H.; Shi, L. Efforts for a Circular Economy in China: A Comprehensive Review of Policies. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, R. Proposing a definition and a framework of organisational sustainability: A review of efforts and a survey of approaches to change. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naudé, M. Sustainable development in companies: Theoretical dream or implementable reality? Corp. Ownersh. Control 2011, 8, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millar, N.; Mclaughlin, E.; Börger, T. The Circular Economy: Swings and Roundabouts? Ecol. Econ. 2019, 158, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cecchin, A.; Salomone, R.; Deutz, P.; Raggi, A.; Cutaia, L. Relating Industrial Symbiosis and Circular Economy to the Sustainable Development Debate. In Industrial Symbiosis for the Circular Economy; Salomone, R., Cecchin, A., Deutz, P., Raggi, A., Cutaia, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, R.; Huisingh, D. Inter-linking issues and dimensions in sustainability reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.R. Organizational Theory, Design, and Change: Text and Cases, 4th ed.; Pearson International Edition; Pearson Education Inc.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Domingues, A.R.; Lozano, R.; Ceulemans, K.; Ramos, T.B. Sustainability reporting in public sector organisations: Exploring the relation between the reporting process and organisational change management for sustainability. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 192, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, V.; Domingues, A.R.; Caeiro, S.; Painho, M.; Antunes, P.; Santos, R.; Videira, N.; Walker, R.M.; Huisingh, D.; Ramos, T.B. Employee-Driven Sustainability Performance Assessment in Public Organisations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guthrie, J.; Ball, A.; Farneti, F. Advancing sustainable management of public and not for profit organizations. Public Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratt, C.; Hallstedt, S.; Robèrt, K.H.; Broman, G.; Oldmark, J. Assessment of criteria development for public procurement from a strategic sustainability perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainville, A. Standards in green public procurement – A framework to enhance innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 167, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Walker, H. Sustainable procurement in the public sector: An international comparative study. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2011, 31, 452–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderman, C.J.; Semeijn, J.; Vluggen, R. Development of sustainability in public sector procurement. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl Sönnichsen, S.; Clement, J. Review of green and sustainable public procurement: Towards circular public procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. Green Public Procurement and the EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; European Parliaments Committee on Environment, Public Health and Food Safety: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zutshi, A.; Sohal, A.S.; Adams, C. Environmental management system adoption by government departments/agencies. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2008, 21, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, M.; Vallés, J. An analysis of the implementation of an environmental management system in a local public administration. J. Environ. Manag. 2007, 82, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JRC. Best Environmental Management Practice for the Public Administration Sector; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Daddi, T.; De Giacomo, M.R.; Frey, M.; Iraldo, F. Analysing the causes of environmental management and audit scheme (EMAS) decrease in Europe. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 2358–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, K.; Balfors, B.; Folkeson, L. Framework for environmental performance measurement in a Swedish public sector organization. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, B.; Urbel-Piirsalu, E.; Anderberg, S.; Olsson, L. Categorising tools for sustainability assessment. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Wilmshurst, T.; Clift, R. Sustainability reporting by local government in Australia: Current and future prospects. Account. Forum 2011, 35, 176–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, F.; Ricci, P. What is the stock of the situation? A bibliometric analysis on social and environmental accounting research in public sector. Int. J. Public Sect. Manag. 2019, 32, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B.; de Melo, J.J. Environmental management practices in the defence sector: Assessment of the Portuguese military’s environmental profile. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B.; de Melo, J.J. Developing and implementing an environmental performance index for the Portuguese military. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2006, 15, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. Jounral Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahel, W.R. The Circular Economy - A User’s Guide; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Migliore, M.; Talamo, C.; Paganin, G. Circular Economy and Sustainable Procurement: The Role of the Attestation of Conformity. In Strategies for Circular Economy and Cross-sectoral Exchanges for Sustainable Building Products; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Marrucci, L.; Daddi, T.; Iraldo, F. The integration of circular economy with sustainable consumption and production tools: Systematic review and future research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhgren, M.; Milios, L.; Dalhammar, C.; Lindahl, M. Public procurement of reconditioned furniture and the potential transition to product service systems solutions. Procedia CIRP 2019, 83, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafoord, K.; Dalhammar, C.; Milios, L. The use of public procurement to incentivize longer lifetime and remanufacturing of computers. Procedia CIRP 2018, 73, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gåvertsson, I.; Milios, L.; Dalhammar, C. Quality Labelling for Re-used ICT Equipment to Support Consumer Choice in the Circular Economy. J. Consum. Policy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alhola, K.; Ryding, S.-O.; Salmenperä, H.; Busch, N.J. Exploiting the Potential of Public Procurement: Opportunities for Circular Economy. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 23, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witjes, S.; Lozano, R. Towards a more Circular Economy: Proposing a framework linking sustainable public procurement and sustainable business models. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 112, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ammenberg, J.; Anderberg, S.; Lönnqvist, T.; Grönkvist, S.; Sandberg, T. Biogas in the transport sector—actor and policy analysis focusing on the demand side in the Stockholm region. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso-Orzáez, M.J.; Lozano-Miralles, J.A.; Lopez-Garcia, R.; Brito, P. Environmental criteria for assessing the competitiveness of public tenders with the replacement of large-scale LEDs in the outdoor lighting of cities as a key element for sustainable development: Case study applied with PROMETHEE methodology. Sustain. 2019, 11, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EC. Public Procurement for a Circular Economy: Good Practices and Guidance; European Union: Brussel, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Building Circularity into our Economies through Sustainable Procurement; United Nations Environment Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- De Groene Zaak. Governments going Circular. 2015. Available online: http://www.govsgocircular.com/ (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Rainville, A. Stimulating a more Circular Economy through Public Procurement: Roles and Dynamics of Intermediation; Vtrek & Maastricht School of Management: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Johnston, K.; ten Cate, J.; Elfering-Petrovic, M.; Gupta, J. City level circular transitions: Barriers and limits in Amsterdam, Utrecht and the Hague. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milios, L.; Holm Christensen, L.; McKinnon, D.; Christensen, C.; Rasch, M.K.; Hallstrøm Eriksen, M. Plastic recycling in the Nordics: A value chain market analysis. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Mejía-Villa, A.; Ormazabal, M.; Jaca, C. Challenges for ecolabeling growth: Lessons from the EU Ecolabel in Spain. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 25, 856–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. Winning hearts and minds: A commentary on circular cities. J. Public Aff. 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. Building a business case for implementation of circular economy in higher education institutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 553–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza, J.M.F.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. A methodological framework for the implementation of circular economy thinking in higher education institutions: Towards sustainable campus management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, B.T.; Pollard, S.J.T.; Burgess, P.J.; Ellis, G.; de los Rios, I.C.; Charnley, F. University contributions to the circular economy: Professing the hidden curriculum. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ganapati, S.; Reddick, C.G. Prospects and challenges of sharing economy for the public sector. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grohmann, D.; Petrucci, R.; Torre, L.; Micheli, M.; Menconi, M.E. Street trees’ management perspectives: Reuse of Tilia sp.’s pruning waste for insulation purposes. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, M. Chapter 3: Public Organizations and Business Model Innovation: The Role of Public Service Design. In Public Sector Entrepreneurship and the Integration of Innovative Business Models; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; Volume i, pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, M. Chapter 5 Public Sector and Circular Business Models: From Public Support Towards Implementation Through Design. In Sustainable Business Models: Principles, Promise, and Practice; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; p. 429. [Google Scholar]

- Torrieri, F.; Fumo, M.; Sarnataro, M.; Ausiello, G. An Integrated Decision Support System for the Sustainable Reuse of the Former Monastery of “Ritiro del Carmine” in Campania Region. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bao, Z.; Lu, W.; Chi, B.; Yuan, H.; Hao, J. Procurement innovation for a circular economy of construction and demolition waste: Lessons learnt from Suzhou, China. Waste Manag. 2019, 99, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.; Mendes, P.; Ribau Teixeira, M. Social life cycle analysis as a tool for sustainable management of illegal waste dumping in municipal services. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, J. Promoting industrial symbiosis network through public-private partnership: A case study of TEDA. In Proceedings of the 2009 3rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Beijing, China, 11–13 June 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbatchev, N.; Zenchanka, S. Current Approaches to Waste Management in Belarus. In International Business, Trade and Institutional Sustainability; Filho, W.L., Borges de Brito, P.R., Frankenberger, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- EC. Closing the Loop - An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy (Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions) No COM(2015) 614 Final; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, T.B. Sustainability assessment: Exploring the frontiers and paradigms of indicator approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutz, P.; Ioppolo, G. From theory to practice: Enhancing the potential policy impact of industrial ecology. Sustainability 2015, 7, 2259–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lozano, R.; von Haartman, R. Reinforcing the Holistic Perspective of Sustainability: Analysis of the Importance of Sustainability Drivers in Organizations. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 522, 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B.; Alves, I.; Subtil, R.; de Melo, J.J. Environmental pressures and impacts of public sector organisations: The case of the Portuguese military. Prog. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 4, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Voet, J. The effectiveness and specificity of change management in a public organization: Transformational leadership and a bureaucratic organizational structure. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Conceptual and empirical studies on circular economy (CE) practices and strategies examined in public sector organizations (PSOs) at the organizational level | Studies on CE policies and governmental interventions referring to the macro level |

| Studies mentioning CE practices and strategies for PSOs, although the public sector might not be the main scope of those studies | Studies mentioning the importance of government as a regulatory entity for society and companies |

| PSO Areas | Publications |

|---|---|

| Public Procurement (PP) | Dahl Sönnichsen and Clement [44] |

| Migliore et al. [61] | |

| Marrucci et al. [62] | |

| Öhgren et al. [63] | |

| Crafoord et al. [64] | |

| Gåvertsson et al. [65] | |

| Alhola et al. [66] | |

| Witjes and Lozano [67] | |

| Ammenberg et al. [68] | |

| Hermoso-Orzáez et al. [69] | |

| EC [70] | |

| UNEP [71] | |

| De Groene Zaak [72] | |

| EMF [24] | |

| Rainville [73] | |

| Campbell-Johnston et al. [74] * | |

| Milios et al. [75] * | |

| Prieto-Sandoval et al. [76] * | |

| Milios [5] * | |

| Internal Processes and Operations | Jones and Comfort [77] |

| Mendoza et al. [78] | |

| Mendoza et al. [79] | |

| Nunes et al. [80] | |

| Seifert et al. [28] | |

| Ganapati and Reddick [81] | |

| EC [10] | |

| Public Service Delivery | Grohmann et al. [82] |

| Lewandowski [83] | |

| Lewandowski [84] | |

| Torrieri et al. [85] | |

| Bao et al. [86] | |

| Santos et al. [87] | |

| Qi et al. [88] | |

| Gorbatchev and Zenchanka [89] |

| PP Practices Category | CE Sub-Category | N° of Good Practice Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Promoting product-focused criteria for CE | Longer Life Span (Remanufacture/Reuse) | 12 |

| Recycled content in products | 13 | |

| Recyclability | 1 | |

| Design for disassembly | 3 | |

| Renewable sources | 5 | |

| New conditions for sustainable use of resources | 6 | |

| Promoting business models for CE | Product-service systems, Leasing | 7 |

| Sharing platforms/services | 2 | |

| Innovative waste management systems | 1 | |

| Total number of circular PP good practice cases | 50 | |

| Sectors | N° of Good Practice Cases |

|---|---|

| Construction and Infrastructure | 12 |

| Furniture | 8 |

| Transportation | 6 |

| ICT products | 6 |

| Waste management and sewage treatment | 5 |

| Food | 3 |

| Textiles | 4 |

| Cleaning products | 3 |

| Print and paper | 2 |

| Cross-sectoral | 1 |

| Total n° of cases | 50 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klein, N.; Ramos, T.B.; Deutz, P. Circular Economy Practices and Strategies in Public Sector Organizations: An Integrative Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104181

Klein N, Ramos TB, Deutz P. Circular Economy Practices and Strategies in Public Sector Organizations: An Integrative Review. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104181

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlein, Natacha, Tomás B. Ramos, and Pauline Deutz. 2020. "Circular Economy Practices and Strategies in Public Sector Organizations: An Integrative Review" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104181

APA StyleKlein, N., Ramos, T. B., & Deutz, P. (2020). Circular Economy Practices and Strategies in Public Sector Organizations: An Integrative Review. Sustainability, 12(10), 4181. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104181