Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability through e-Learning in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The general idea: There is a topic presented to students with importance to society.

- The essential question: The general idea starts with a problem that reflects the interest of the students and the needs of the community.

- The challenge: Students must create a solution to the problem posed in the essential question.

- Questions, activities, and guide resources: Students identify elements that are convenient for developing innovative solutions to problems.

- The solution: Each challenge permits a variety of solutions. These must be concrete and feasible to implement in the community.

- Implementation: Students test the solution in a real environment.

- The evaluation or assessment is carried out through the challenge process, which confirms the learning results and supports the decisions made during the implementation.

- Documentation and publication: Students find ways to publish their ideas, blogs, videos, and other tools.

- Reflection and dialogue that consider the content and the students’ learning and experiences.

- Q1. How to implement CBL to strengthen education for sustainable development in an e-learning course in the study context?

- Q2. What was the perception of the enrolled students in the e-learning course about the contribution they can make to resolving local, national, or global problems?

- Q3. What elements of CBL contribute to providing solutions to local problems through an e-learning course?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

- To clearly explain the objectives of the study, telling the participants that the course was a research project.

- To allow researchers to personally visit the class and explain the work to be done, answer any questions, and explain the time involved and procedures to be followed during the research.

- To emphasize that participation was voluntary, and that all data would remain confidential.

- To explain to the participants that they could decide not to participate in the research at any time. An online form was sent to them with the terms requesting their acceptance in the study.

2.3. Instruments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Forum Content Analysis

- Opinion on entrepreneurship: Students related entrepreneurship to economic growth and job creation, as well as to the achievement of skills and capacities and personal development. Student comments from the forum included, “for me, entrepreneurship is focusing on a problem that you consider important to solve”, “to improve people’s opportunities and quality of life”, and “improvement of culture and way of thinking of society”.

- Difficulties: Studnets expressed their concerns about how they could contribute to solving social problems, improve peoples’ qualities of life, and how, through their careers, they could generate ideas and propose businesses that could solve these problems. They indicated that they did not know how to undertake these things or if they had the skills. Also, they responded that entrepreneurship was not highlighted in their fields of study, that socially responsible production is a “pending” task in companies, and that they were not clear which businesses to start. They identified a delay in the country in developing ventures. Their comments included, “I am not clear which business to start; I must know its advantages and disadvantages. I feel that I have not developed the abilities needed for entrepreneurship”, “I think it is necessary to know more about the subject in-depth and how to develop these skills in us better”, and “socially responsible production is a pending task in companies”.

- Interests: The students expressed great interest in undertaking social projects and interest in solving social problems. They mentioned issues such as pollution, the use of polluting materials in industrial applications, the insertion of older people into the workforce, the development of the best sustainable practices, and avoiding food waste and water and air pollution, among other issues. Their comments included, “I want to undertake a social project whose objective is the reintegration of seniors into the work environment; I encourage that companies obtain a special badge that qualifies them as socially responsible companies”, “I want to create an environmental consultancy and an environmental remediation company in contaminated places”, and “I am interested in this course because, in the future, I want to launch a startup”.

3.2. Participation in the Challenge

- A social enterprise that honors companies that adopt senior mentoring programs, that trains young people, and in which lack of experience is not an impediment for new employees.

- A platform to support the commercialization of products through employing young people remotely, and the digitalization of government information for greater transparency.

- A proposal to eradicate the extreme poverty of food in the state of Nuevo León and facilitate access to health services.

- A proposal to decrease carbon dioxide in the companies that emit it.

- A proposal for an environmental consulting agency that gives incentives to companies that reduce their emissions.

- A proposal to use plants to reduce air pollution.

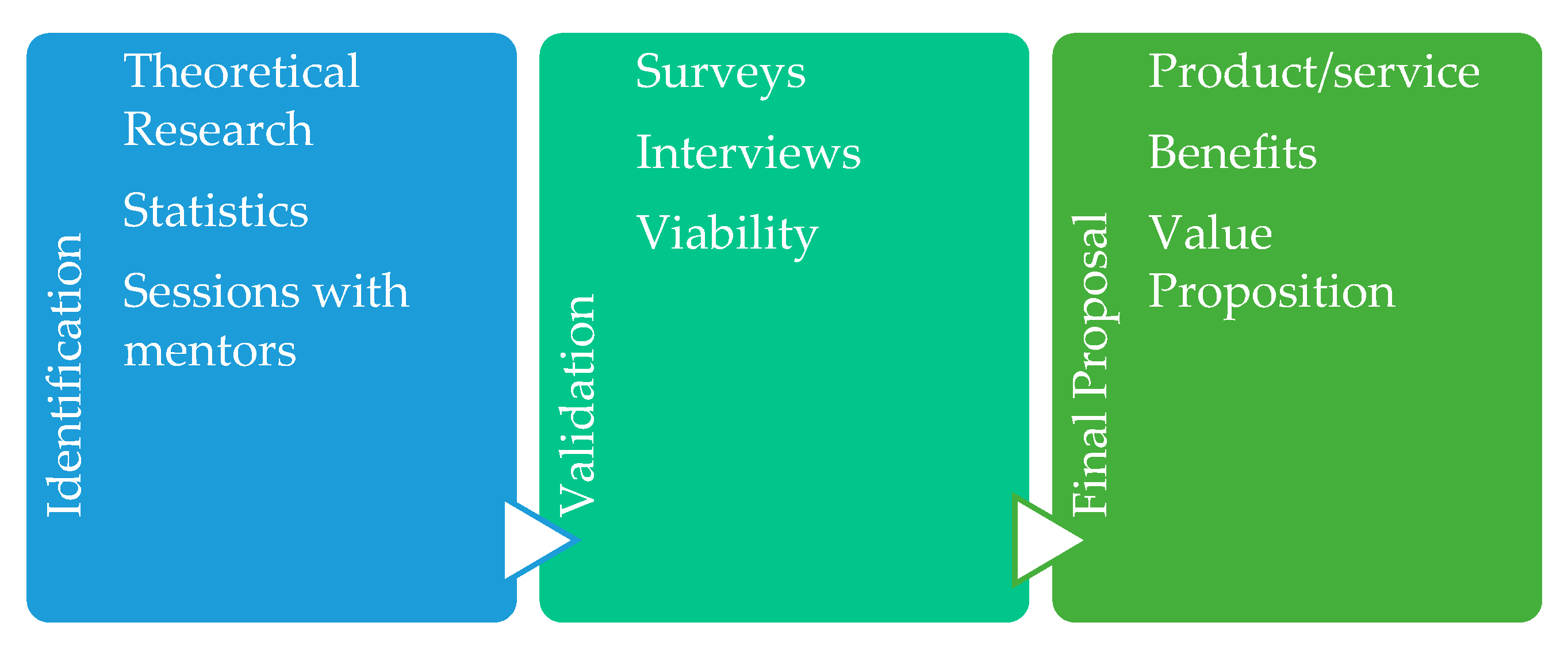

- Projects resolving problems related to the students’ careers, theoretical research, and statistics they collected to establish the magnitudes of the problems, as well as analyses of the impacts of the solutions.

- Research on the problems using interviews and the applications of the business model canvas to determine the people affected.

- Consultations with people affected by the problems and feasibility analysis of each solution’s implementation.

- Presentation of a proposal defining a product or service, the benefits of the solution proposed for the priority area, data related to the impact of the solution, and a value proposition.

3.3. Solution Proposals

3.4. Responses to the Questionnaires

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khaddage, F.; Christensen, R.; Lai, W.; Knezek, G.; Norris, C.; Soloway, E. A model-driven framework to address challenges in a mobile learning environment. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2015, 20, 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cano, E.; López Meneses, E.; Jaén Martínez, A. The group e-portfolio to improve the teaching-learning process at university. J. e-Learn. Knowl. Soc. 2017, 13, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozuorcun, N.C.; Tabak, F. Is M-learning versus E-learning, or are they supporting each other? Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero Fernández, B. Estudios sobre propuestas y experiencias de innovación educativa. Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 2018, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huss, J.A.; Sela, O.; Eastep, S. A case study of online instructors and their quest for greater interactivity in their courses: Overcoming the distance in distance education. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 40, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racovita-Szilagyi, L.; Carbonero Muñoz, D.; Diaconu, M. Challenges and opportunities to eLearning in social work education: Perspectives from Spain and the United States. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2018, 21, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemán de la Garza, L.; Gómez Zermeño, M.; Mochizuki, Y.; Bruillard, E.; Anichini, A.; Antal, P.; Beaune, A.; Bruillard, E.; Burke, D.; Henrique Cacique Braga, P.; et al. Rethinking Pedagogy. Exploring the Potential of Digital Technology in Achieving Quality Education; UNESCO MGIEP: New Delhi, India, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.; Neergaard, H.; Tanggaard, L.; Krueger, N. New horizons in entrepreneurship education: From teacher-led to student-centered learning. Educ. Train. 2016, 58, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera Vargas, P.; Alonso Cano, C.; Sancho Gil, J. Desde la educación a distancia al e-learning: Emergencia, evolución y consolidación. Revista Educ. y Tec. 2017, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/es/education/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Lozano, R.; Lukman, R.; Lozano, F.; Huisingh, D.; Lambrechts, W. Declarations for sustainability in higher education: Becoming better leaders, through addressing the university system. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeiteiro, U.; Bacelar Nicolau, P.; Caetano, F.; Caeiro, S. Education for sustainable development through e-learning in higher education: Experiences from Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Available online: https://gem-report-2016.unesco.org/es/chapter/la-prosperidad-economias-sostenibles-e-inclusivas/ (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000252423/PDF/252423spa.pdf.multi (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Parra, S. Exploring the incorporation of values for sustainable entrepreneurship teaching/learning. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 8, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Sustainable Development Goals: A need for relevant indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 60, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.; Halsz, G.; Krawczyk, M.; Leney, T.; Micehl, A.; Pepper, D.; Putkiewicz, E.; Wisniewski, W. Key Competences in Europe: Opening Doors for Lifelong Learners across the School Curriculum and Teacher’s Education; Centre for Social and Economic Research on behalf of CASE Network: Warsaw, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Camacho Yáñez, I.; Gómez Zermeño, M.; Pintor Chávez, M. Competencias digitales en el estudiante adulto trabajador. Revista Interamericana de Educación de Adultos 2015, 37, 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Alcalá del Olmo, M.; Gutiérrez Sánchez, J. El desarrollo sostenible como reto pedagógico de la universidad del siglo XXI. Anduli 2019, 19, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takala, A.; Korhonen-Yrjänheikki, K. A decade of Finnish engineering education for sustainable development. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2019, 20, 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Zein, A.H.; Hedemann, C. Beyond problem solving: Engineering and the public good in the 21st century. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaci, A.; Dagnino, F.; Ott, M.; Bellotti, F.; Berta, R.; De Gloria, A.; Lavagnino, E.; Romero, M.; Usart, M.; Mayer, M. Gamified collaborative course in entrepreneurship: Focus on objectives and tools. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 51, 1276–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzeviciute, V.; Praneviciene, B.; Simanaviciene, Z.; Vasiliauskiene, V. Competence for sustainability: Prevention of dis-balance in higher education: The case of cooperation while educating future law enforcement officers. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2017, 13, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.; Osborne, M. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerization? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, N.; Wrigley, C. Broadening design-led education horizons: Conceptual insights and future research directions. Int. J. Technol. Des. Ed. 2019, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.; Khan, E.; Nabi, M. Entrepreneurial education at the university level and entrepreneurship development. Educ. Train. 2018, 59, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffeei, S.; Yusop, F.; Kamarulzaman, Y. Determinants of innovation culture amongst higher education students. Turkish Online J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 17, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; de Vries, W.T. Sustaining a culture of excellence: Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) on land management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A.; García, F.; Zubieta Ramírez, C.; López Cruz, C. Competencies associated with Semestre i and its relationship to academic performance. High. Educ. Skills Work-Based Learn 2019, 10, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edutrends. Aprendizaje Basado en Retos; Observatorio de Innovación Educativa del Tecnológico de Monterrey: Monterrey, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhoua, Y.; Chung, J.; Tang, Q.; Jiang, L.; Wong, K. Challenge Based Learning nurtures creative thinking: An evaluative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 71, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rådberg, K.; Lundqvist, U.; Malmqvist, J.; Svensson, O. From CDIO to challenge-based learning experiences –expanding student learning as well as societal impact? Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 2020, 45, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmqvist, J.; Rådberg, K.; Lundqvist, U. Comparative analysis of challenge-based learning experiences. In Proceedings of the 11th International CDIO Conference, Chengdu, Sichuan, China, 8–11 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, C.; Klein-Gardner, S. A study of challenge-based learning techniques in an introduction to engineering course. In Proceedings of the 2007 Annual Conference & Exposition, Honolulu, Hawaii, 24 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo Blanco, A.; Sein-Echaluce, M.; García Peñalvo, F. Aprendizaje Basado en Retos en una asignatura académica universitaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Informática Educativa 2017, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, M.; Aznar, J.; Galiana, J.; Rocafort-Marco, A. An explanatory study of MBA students with regards to sustainability and ethics commitment. Sustainability 2016, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttilä, T. Desarrollo de organizaciones educativas con pedagogía de innovación. J. Adv. Educ. 2016, 2, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Portuguez Castro, M.; Ross Scheede, C.; Gómez Zermeño, M. The impact of higher education in entrepreneurship and the innovation ecosystem: A case study in Mexico. Sustainability 2019, 20, 5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.; Seoane Pardo, A. Una revisión actualizada del concepto de eLearning. Décimo Aniversario. Educ. Knowl. Soc. 2015, 16, 119–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design. Choosing Among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Otzen, T.; Manterola, C. Técnicas de Muestreo sobre una Población a Estudio. Intern. J. Morphol. 2017, 35, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consejo Nuevo León para la Planeación Estratégica. Plan Estratégico para el Estado de Nuevo León 2015–2030; Consejo de Nuevo León: Monterrey, Mexico, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute for Qualitative Methodology. Available online: https://sites.ualberta.ca/~iiqm/pdfs/introduccion.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Hernández-de-Menéndez, M.; Vallejo Guevara, A.; Tudón Martínez, J.C. Active learning in engineering education. A review of fundamentals, best practices, and experiences. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2019, 13, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajabion, L.; Wakil, K.; Badfar, A.; Nazif, M.; Ehsani, A. A new model for evaluating the effect of cloud computing on the e-learning development. J. Workplace Learn. 2019, 31, 324–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindt, L.; Rieckmann, M. Developing competencies for sustainability-driven entrepreneurship in higher education: A literature review of teaching and learning methods. Teoría de la Educación 2017, 29, 129–159. [Google Scholar]

| Total Students | Men | Women | Average Age | Career |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 8 | 12 | 23 years old | |

12 6 1 1 | 40% 5 2 1 0 | 60% 7 4 0 1 | Engineering Business administration Industrial design Clinical psychology |

| Learning Objectives | Week | Activities | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| To describe concepts related to entrepreneurship and innovation for use in solving problems in their environment. | 1. Introduction to the course | Forum: What do you think is the importance of entrepreneurship and innovation in our country? | Participate in the forum and comment on at least two interactions by partners. Checklist. |

| To analyze problematic situations in the local environment that can be resolved through innovative and entrepreneurial proposals. | 2.Presentation of the challenge | Presentation of the challenge: individually, students reviewed the challenge, and one of the priority areas to be solved was chosen. | Participate in the team forum by choosing a topic and proposing a possible solution to the problem. Checklist. |

| To propose innovative solutions to problems collaboratively and with the help of a mentor. | 3. Preparation of solution proposals | Brainstorming forum to coordinate the group work and define a solution proposal collaboratively. Meet with partners to solve the challenge (through videoconference/chat/forum). | Participate in the group forum to coordinate the activity and propose the solution. Checklist. |

| To prepare a pitch to publicize the proposed solution | 4. Final pitch | Present the final pitch following the instructions of the evaluation rubric. | Present a pitch that includes the problem to be solved, the proposed solution, and a conclusion. Rubric. |

| 5. Final evaluation | Final Reflection: Write a personal story by answering questions about the experience. | Publish your entrepreneurship story on your blog. Checklist. |

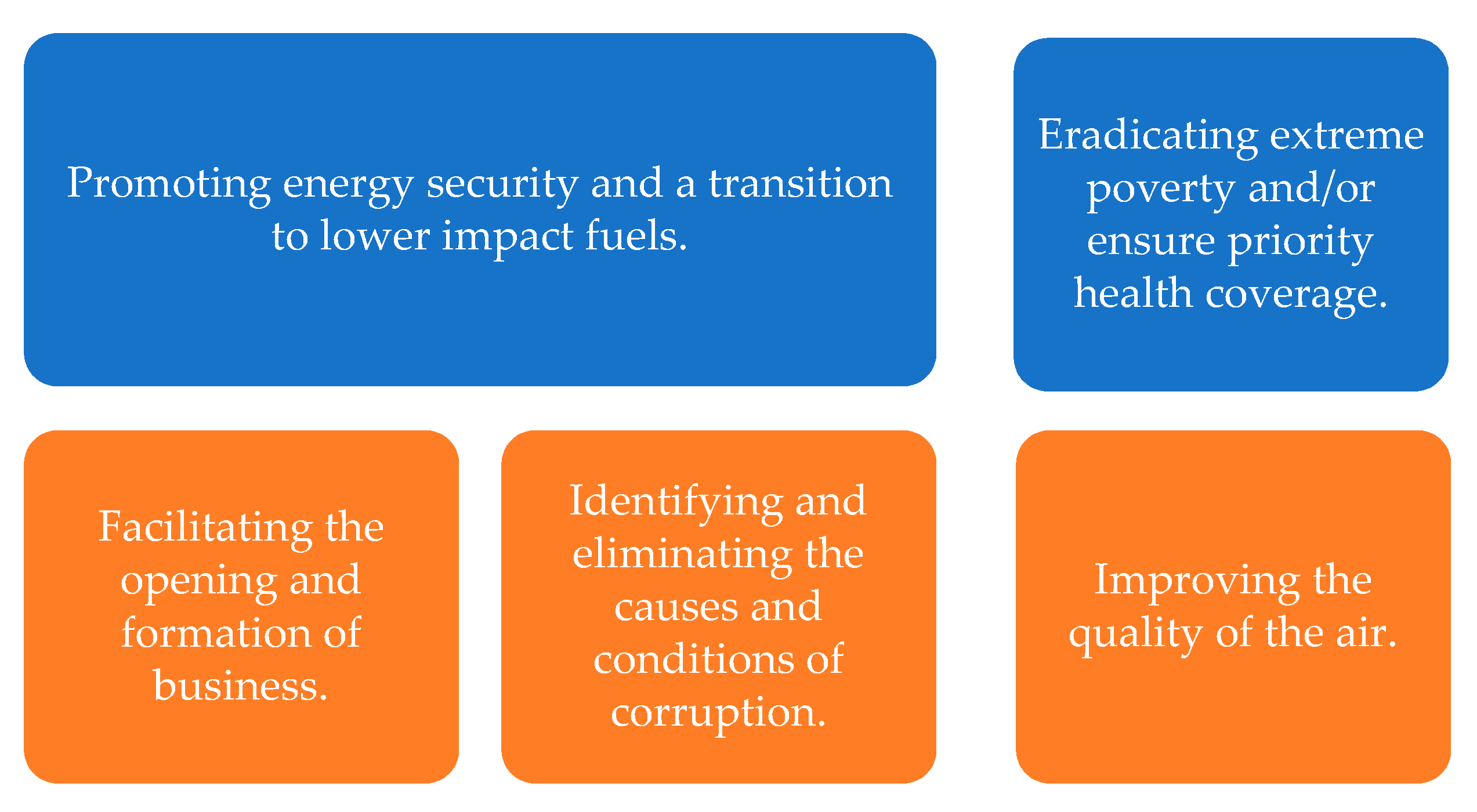

| Priority Areas | Relationship to SDG |

|---|---|

| Eradicating extreme poverty with particular emphasis on nutrition | Objectives 1 and 2: End of poverty and zero hunger |

| Ensuring coverage and effective access of the population to healthcare for priority health conditions | Objective 3: Health and well-being |

| Ensuring the employability of young people in the productive sector | Objective 8: Decent work and economic growth |

| Generate training programs in reading, written culture, and development of artistic skills | Objective 4: Quality education |

| Encouraging physical activity and sports | Objective 3: Health and well-being |

| Improving air quality | Objective 11: Sustainable cities and communities |

| Facilitating the opening and operation of businesses | Objective 8: Decent work and economic growth |

| Identifying and eliminating causes, conditions, and factors of corruption | Objective 16: Peace, justice, and strong institutions. |

| Promoting energy security and a transition to lower-impact fuels | Objective 7: Affordable, non-polluting energy |

| Strengthening and promoting community and neighborhood cultures to generate social cohesion and citizen coexistence | Objective 16: Peace, justice, and strong institutions |

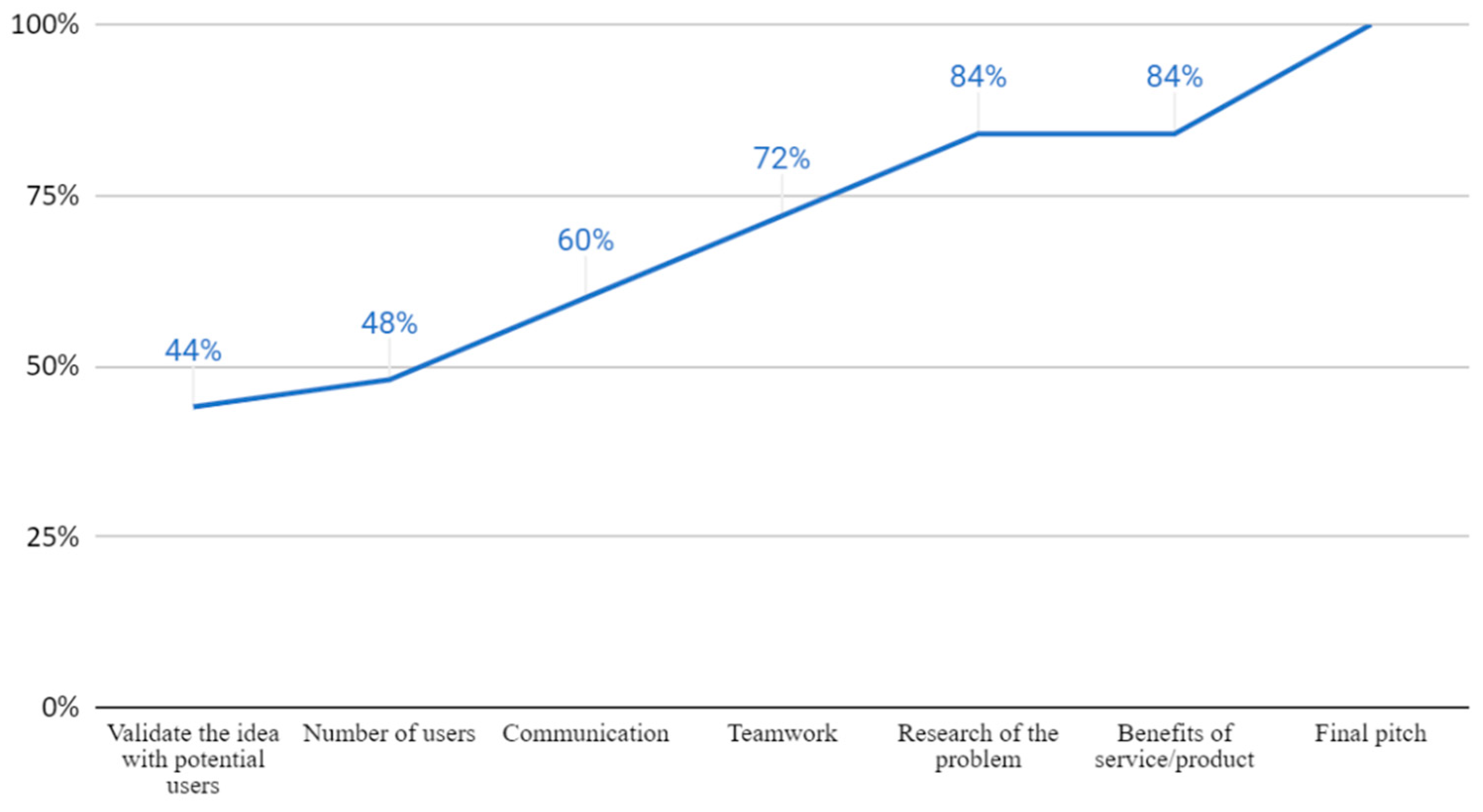

| Name of the Product or Service | Score (1–5) |

|---|---|

| Teamwork | |

| Included research on the subject | |

| Included statistics on the problem | |

| Defined the number of users | |

| Validated the idea with potential users | |

| Elaborated a final pitch | |

| Presented interesting data or information | |

| Presented the benefits of the product or service | |

| Presentation of the pitch | |

| Points earned |

| Problem | The solution that Addresses the Problem |

|---|---|

| Promoting energy security and a transition to low-impact fuels | Biodigestor to produce biogas |

| Eradicating extreme poverty and ensuring priority health coverage | An educational program focused on healthy alimentation |

| Facilitating the opening and formation of businesses | Various mentors |

| Improving the quality of the air. | Vertical gardens |

| Identifying and eliminating the causes and conditions of corruption | The final proposal not presented. |

| Improving the quality of the air | The capture of contaminants in chimneys by a microalgae biofilter |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Portuguez Castro, M.; Gómez Zermeño, M.G. Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability through e-Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104063

Portuguez Castro M, Gómez Zermeño MG. Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability through e-Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104063

Chicago/Turabian StylePortuguez Castro, May, and Marcela Georgina Gómez Zermeño. 2020. "Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability through e-Learning in Higher Education" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104063

APA StylePortuguez Castro, M., & Gómez Zermeño, M. G. (2020). Challenge Based Learning: Innovative Pedagogy for Sustainability through e-Learning in Higher Education. Sustainability, 12(10), 4063. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104063