Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: The Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Kuala Lumpur Heritage Area and Challenges

Heritage protection is not against development – it can go hand in hand rather successfully if plans are conceived with heritage in mind. We want a city that could recognise itself developed not at the expense of our historic chronology and a better quality of life. As the guardian of Kuala Lumpur’s history and heritage, Kuala Lumpur City Hall must make obvious attempts to safeguard the city’s heritage assets. Unless a focus is placed on heritage matters transparently, the ‘City for All’ will end up just another conceptual slogan and what lies ahead would be the same problems and issues we have yet to solve [4].

Clause 125: We will support the leveraging of cultural heritage for sustainable urban development and recognize its role in stimulating participation and responsibility. We will promote innovative and sustainable use of architectural monuments and sites, with the intention of value creation, through respectful restoration and adaptation. We will engage indigenous peoples and local communities in the promotion and dissemination of knowledge of tangible and intangible cultural heritage and protection of traditional expressions and languages, including through the use of new technologies and techniques [7].

2.2. Design Intervention in the Heritage Area

3. Objectives and Methodology

- Group A: Traders and business owners in heritage area (Petaling Street, R(A)1 to R(A)10, and Kasturi Walk, R(A)11 to R(A)17)

- Group B: Officers in Kuala Lumpur City Hall

- Group C: Professionals

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Najib, A.A. Traditional Architectural Heritage for Modern Malaysian Buildings; Department of National Heritage, Ministry of Information, Communications and Culture: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2013; ISBN 9789833862238. Available online: https://books.google.com.sa/books?id=k-XKoAEACAAJ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Kammeier, H.D. Global Concerns-Local Responsibilities-Global and Local Benefits: The Growing Business of World Heritage. In Proceedings of the 39th ISOCARP Congress, Cairo, Egypt, 17–22 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shuhana, S.; Wan Hashimah, W.I.; Shamsuddin, S. The old shophouses as part of Malaysia urban heritage: The current Dilemma. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of the Asian Planning Schools Association, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3–8 July 2016. [Google Scholar]

- The Kuala Lumpur Heritage Agenda. Review & Recommendations for the Kuala Lumpur Draft Structure Plan 2024 & Kuala Lumpur City Plan 2020; ICOMOS Malaysia: Jalan Tandok, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Draft Kuala Lumpur Structure Plan 2040. Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (DBKL), 2020. Available online: http://www.dbkl.gov.my/klmycity2040/klsp2040/ (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2019. United Nations, 2019. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2019.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- New Urban Agenda. United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III), Equador. United Nations, 2017. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Savage, V.R. Street culture in colonial Singapore. In Public Space: Design, Use and Management; Beng-Huat, C., Edwards, N., Eds.; Singapore University Press: Singapore, 1992; pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ngiom; Lilian, T. 80 Years of Architecture in Malaysia; PAM Publication: Pertubuhan Akitek, Malaysia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lumpur, D.K. Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (DBKL); City Plan 2020; Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Bhd: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Nurulhuda, A.H.Y.; Anuar, M.N.; Rosmadi, G. City skyline conservation: Sustaining the premier image of Kuala Lumpur. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 20, 583–592. [Google Scholar]

- Heritage Homeowner’s Preservation Manual: World Heritage City of Vigan Philippines; UNESCO Bangkok: Bangkok, Thailand; City Government of Vigan: Vigan, Philippines, 2010; 166p, ISBN 978-92-9223-319-8. Available online: http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/library/edocuments/vigan-sample_text.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2020).

- Elder, C. New Design in Historic Settings. Available online: https://pub-prod-sdk.azurewebsites.net/api/ (accessed on 10 August 2015).

- Damla, M. New Designs in Historic Context: Starchitecture vs Architectural Conservation Principles; Department of Architecture, Girne American University: Kyrenia, Northern Cyprus, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, J. The Historic Context: Principles and Philosophies. In Context: New Buildings in Historic Settings; Warren, J., Worthington, J., Taylor, S., Eds.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, T. Landscape Planning And Environmental Impact Design; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, S. Modern Architecture’s place in the city: Divergent Approaches to Historical Core. In Context: New Buildings in Historic Settings; Warren, J., Worthington, J., Taylor, S., Eds.; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, L.Y. Singapore’s Experience in Conservation. In Proceedings of the International Housing Conference of Hong Kong Housing Society, Hong Kong, China, 10–11 April 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, P.; Huang, S. Tourism and heritage conservation in Singapore. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 589–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publication: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, H. The Logic of Qualitative Survey Research and its Position in the Field of Social Research Methods [63 paragraphs]. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum: Qual. Soc. Res. 2010, 11, 11. [Google Scholar]

| Respondent (Group) | Gender | Age | Role/Occupation | Interview Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R(A)1 | F | 40–50 | Plastic houseware seller | Face-to face, survey interview (open-ended unstructured) |

| R(A)2 | F | 40–50 | Roasted meat peddler | |

| R(A)3 | F | 30–40 | Florist | |

| R(A)4 | M | 50–60 | Dried fruit seller | |

| R(A)5 | F | 40–50 | Fresh fruit seller | |

| R(A)6 | M | 50–60 | Fresh fruit seller | |

| R(A)7 | M | 50–60 | Souvenir shop owner | |

| R(A)8 | F | 50–60 | Souvenir shop owner | |

| R(A)9 | M | 30–40 | T-shirt seller | |

| R(A)10 | F | 40–50 | Herbal tea shopkeeper | |

| R(A)11 | F | 30–40 | Phone accessories seller | |

| R(A)12 | M | 50–60 | Batik shop owner | |

| R(A)13 | F | 20–30 | Souvenir shop owner | |

| R(A)14 | M | 30–40 | Souvenir shop owner | |

| R(A)15 | M | 30–40 | Souvenir shop seller | |

| R(A)16 | F | 20–30 | Fruit juice shopkeeper | |

| R(A)17 | F | 30–40 | Traditional sweets seller | |

| R(B)1 | F | 20–30 | City Hall Officer | In-depth interview (open-ended structured) |

| R(B)2 | F | 20–30 | City Hall Officer | |

| R(C)1 | M | 30–40 | Architect/Academician | Expert opinions (open-ended unstructured) |

| R(C)2 | M | 30–40 | Architect/Academician | |

| R(C)3 | M | 40–50 | Architect/Academician | |

| R(C)4 | M | 40–50 | Architect/Academician | |

| R(C)5 | F | 40–50 | Architect/Academician | |

| R(C)6 | F | 30–40 | Architect/Conservator | |

| R(C)7 | M | 40–50 | Architect/Conservator | |

| R(C)8 | M | 70–80 | Architect | |

| R(C)9 | F | 50–60 | Architect | |

| R(C)10 | M | 30–40 | Urban Planner | |

| R(C)11 | M | 30–40 | Urban Planner | |

| R(C)12 | M | 30–40 | Structure Engineer |

|

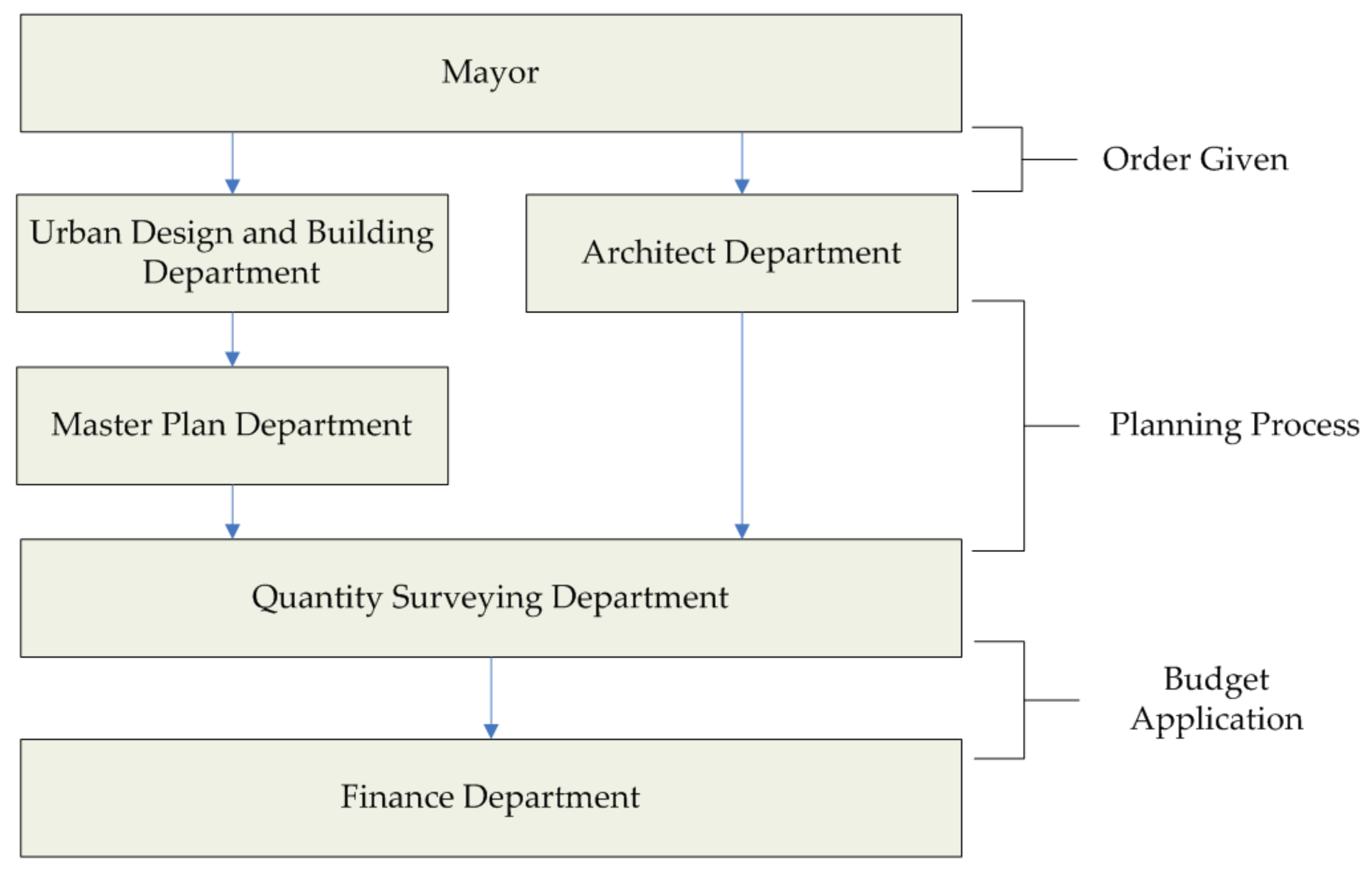

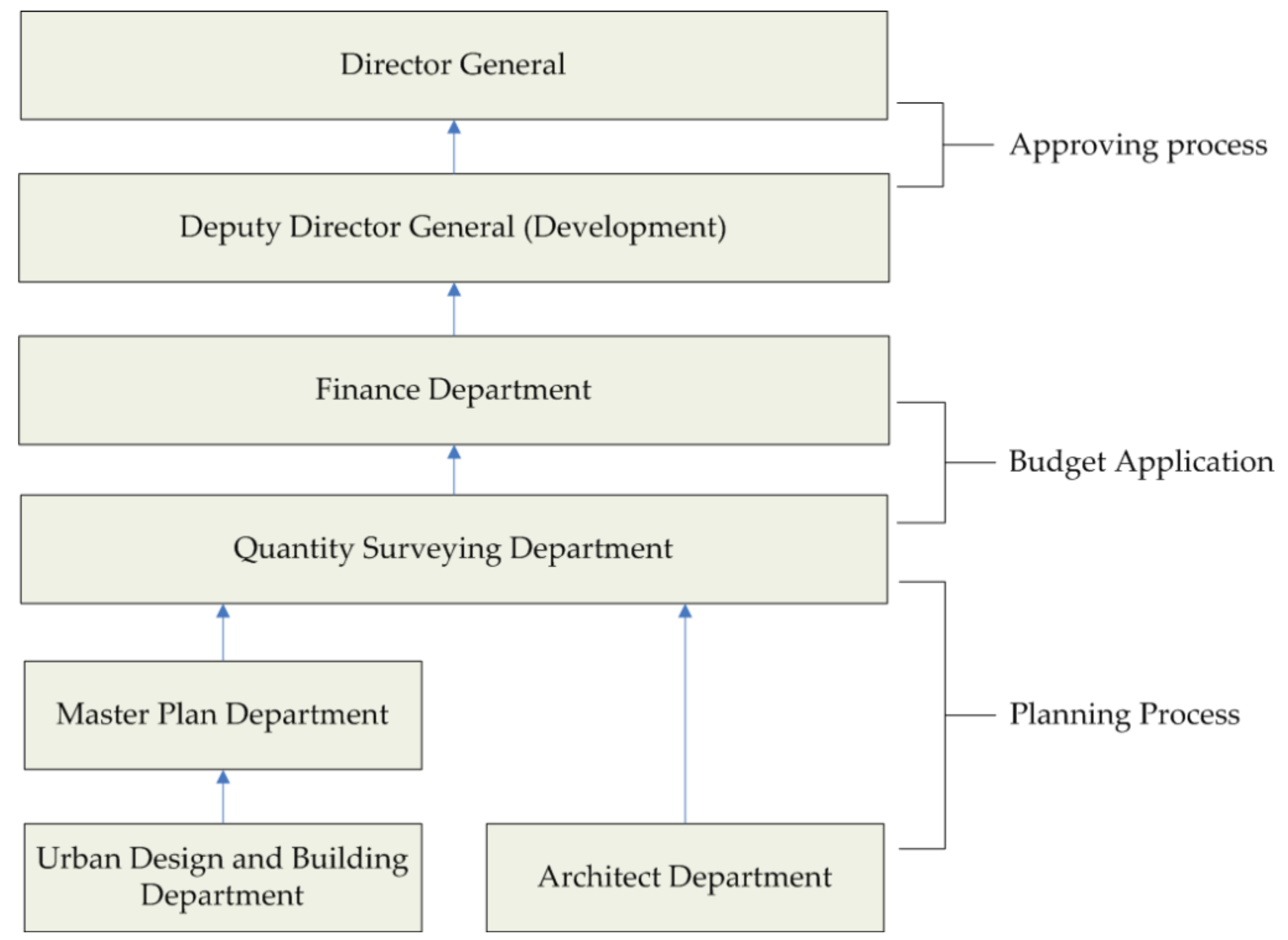

| No. | Department | Functions (Related to Conservation and Beautification Project) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Architect Department |

|

| 2 | Urban Design and Building Department |

|

| 3 | Master Plan Department |

|

| 4 | Quantity Surveying Department |

|

| 5 | Public Works Department |

|

| 6 | Finance Department |

|

| 7 | Urban Transportation Department |

|

| Respondents | Narrative Theme | Quotations |

|---|---|---|

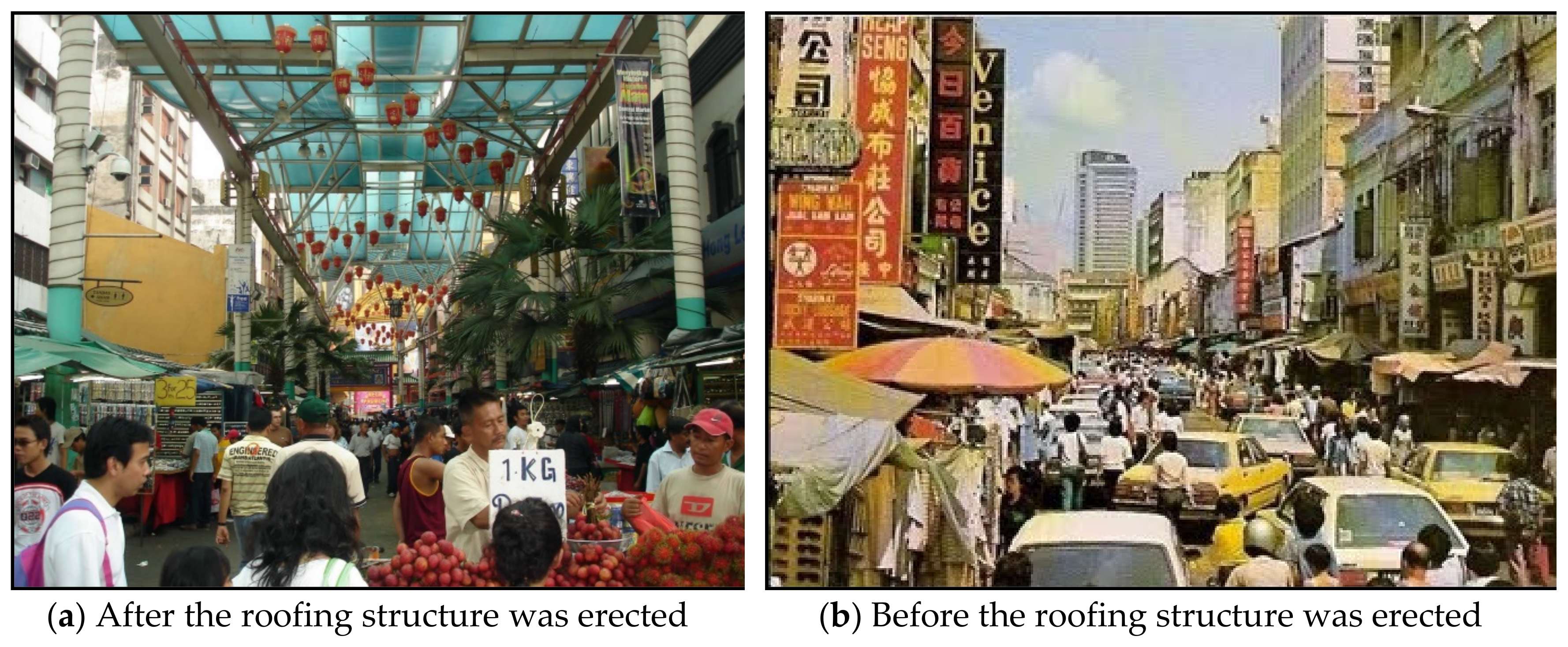

| Group A | The roof structure is helpful |

|

| The business routine does not change |

| |

| Does not aware of the design process |

| |

| The decreasing number of Chinatown residents |

| |

| Lack of parking |

| |

| Competition |

| |

| Rental against profit |

| |

| The lack of cultural and heritage awareness |

| |

| Group C | Design a lack of esthetic |

|

| Over-tourism |

| |

| Decaying heritage buildings |

| |

| Unclear on conservation procedure |

| |

| The pedestrianization of historical street |

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bindajam, A.; Hisham, F.; Al-Ansi, N.; Mallick, J. Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: The Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104028

Bindajam A, Hisham F, Al-Ansi N, Mallick J. Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: The Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur. Sustainability. 2020; 12(10):4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104028

Chicago/Turabian StyleBindajam, Ahmed, Fadrul Hisham, Nashwan Al-Ansi, and Javed Mallick. 2020. "Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: The Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur" Sustainability 12, no. 10: 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104028

APA StyleBindajam, A., Hisham, F., Al-Ansi, N., & Mallick, J. (2020). Issues Regarding the Design Intervention and Conservation of Heritage Areas: The Historical Pedestrian Streets of Kuala Lumpur. Sustainability, 12(10), 4028. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104028