Stakeholder Legitimization of the Provision of Emergency Centralized Accommodations to Displaced Persons

Abstract

1. Introduction

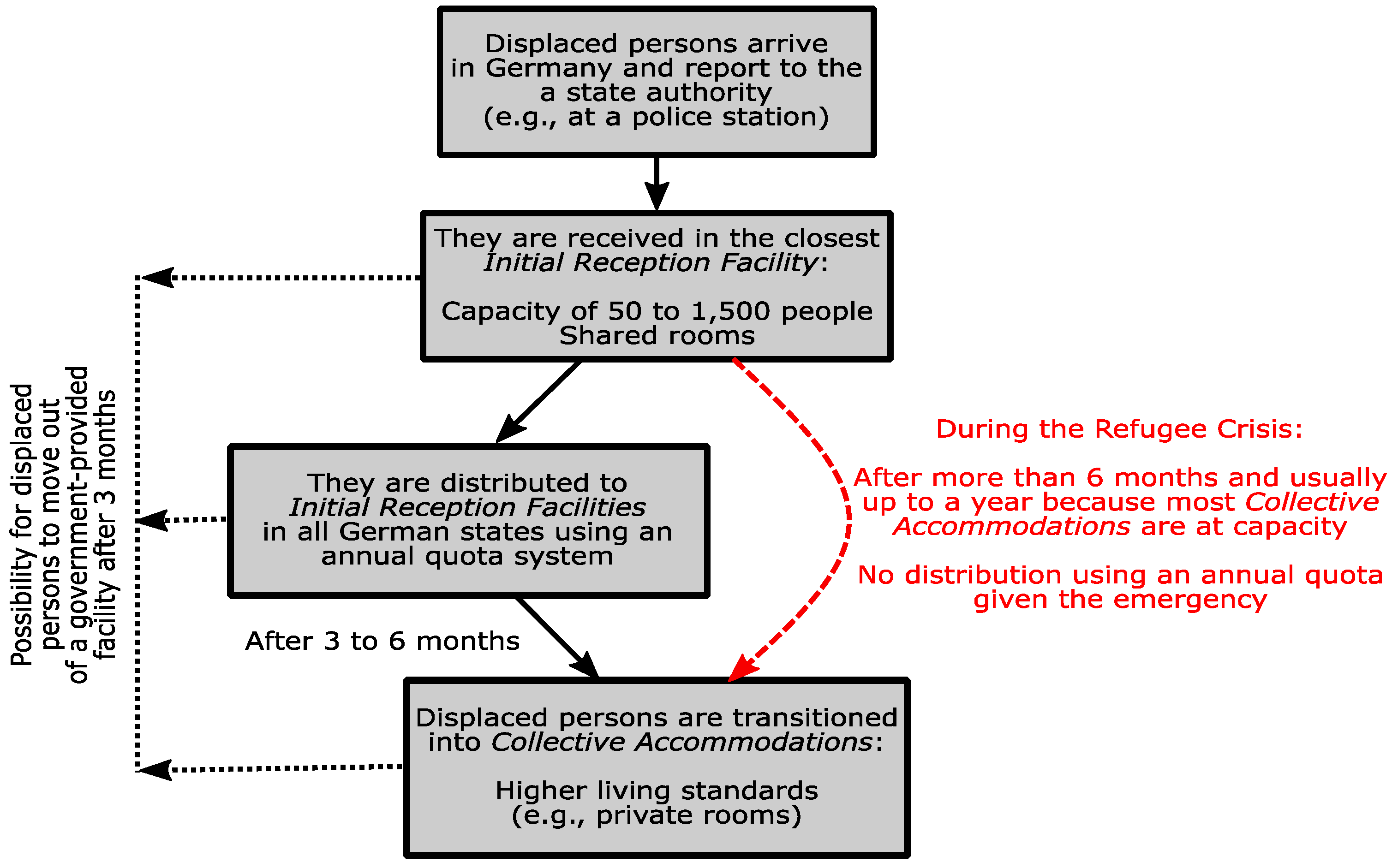

1.1. Overview of the Process of Accommodation of Displaced Persons in Germany

1.2. Accommodations During Emergency Situations

1.3. Legitimacy Theory

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

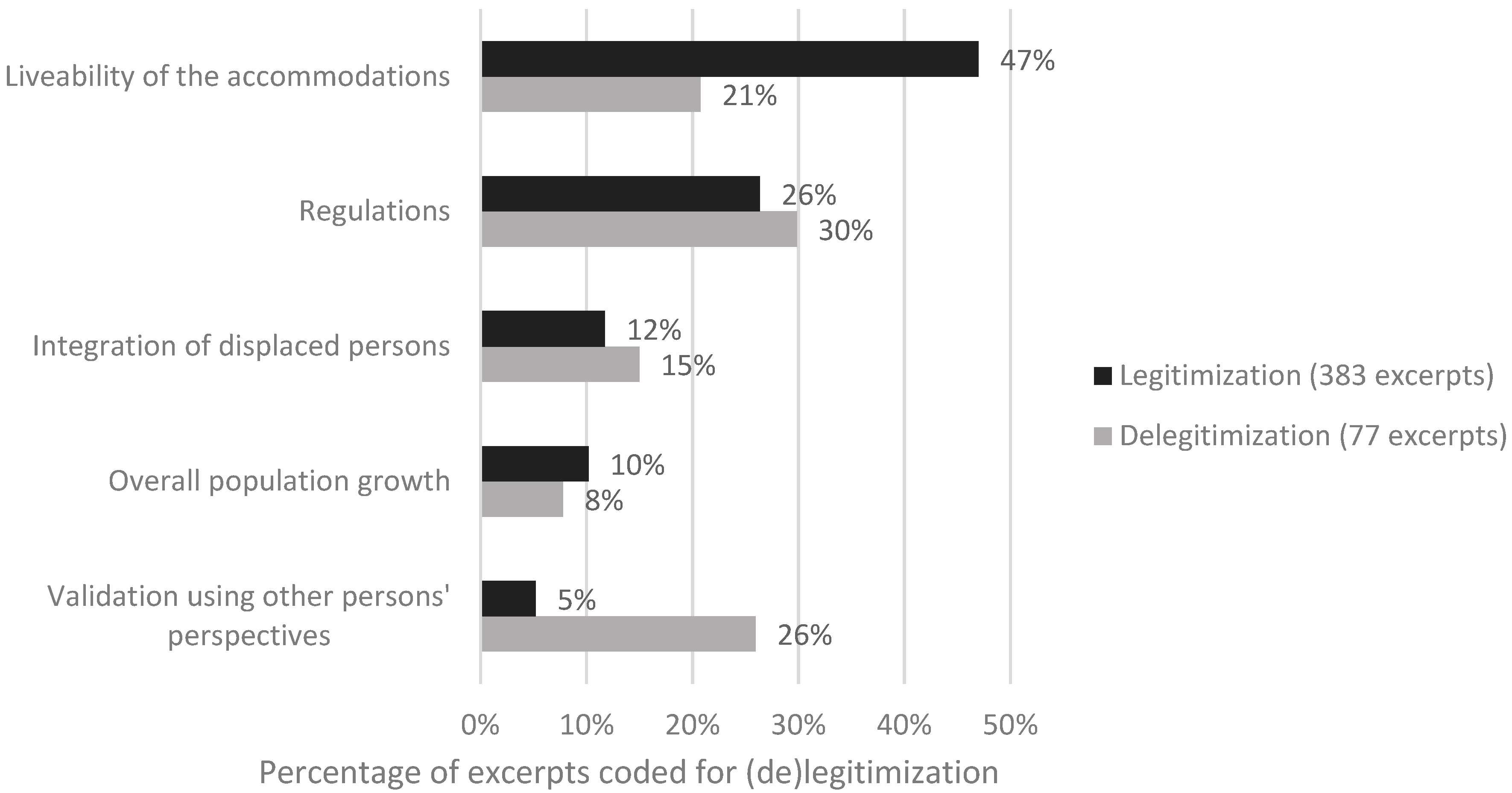

3.1. Stakeholder (De)legitimization of Providing Centralized Accommodations to Displaced Persons

3.1.1. Reasons Explicitly Mentioned

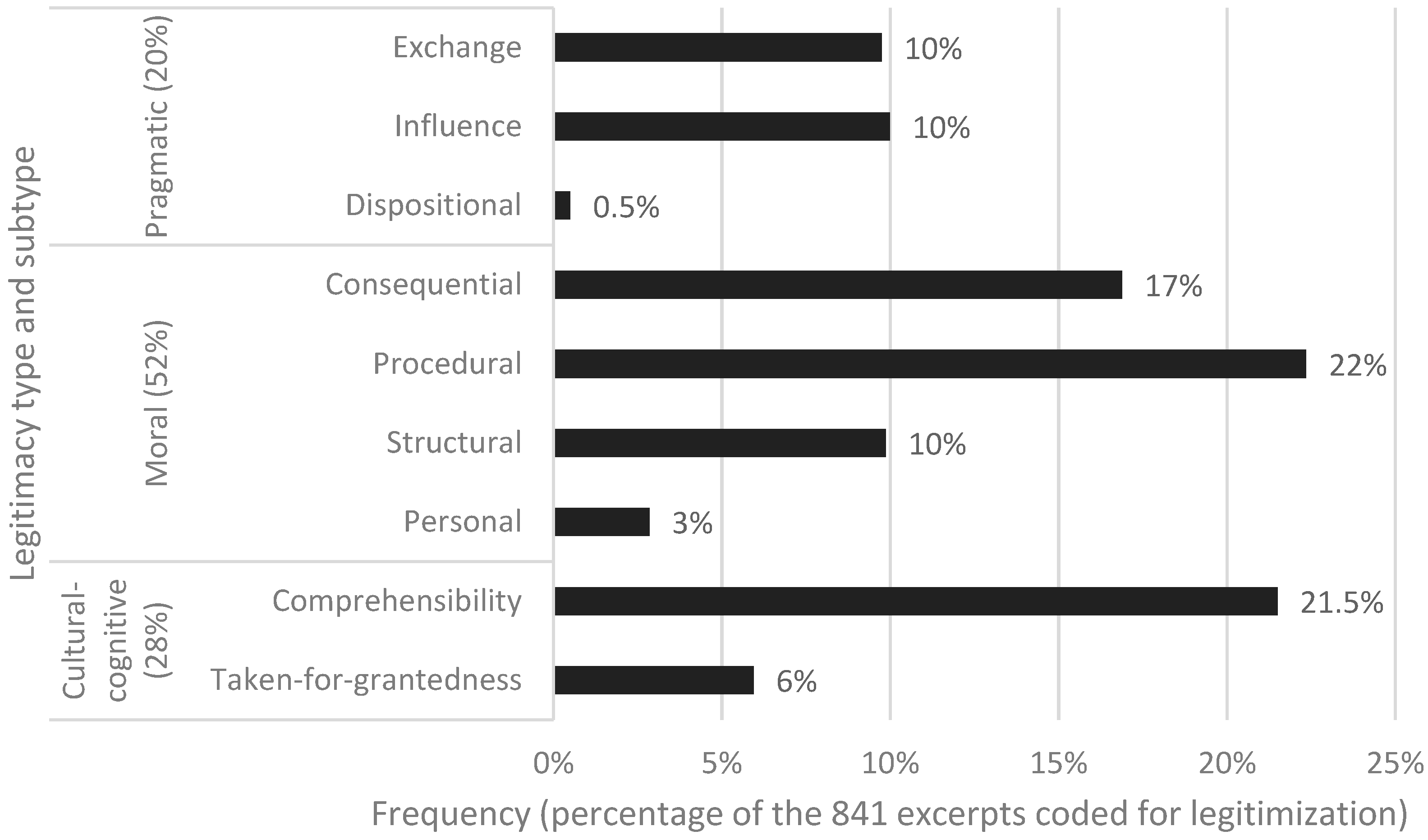

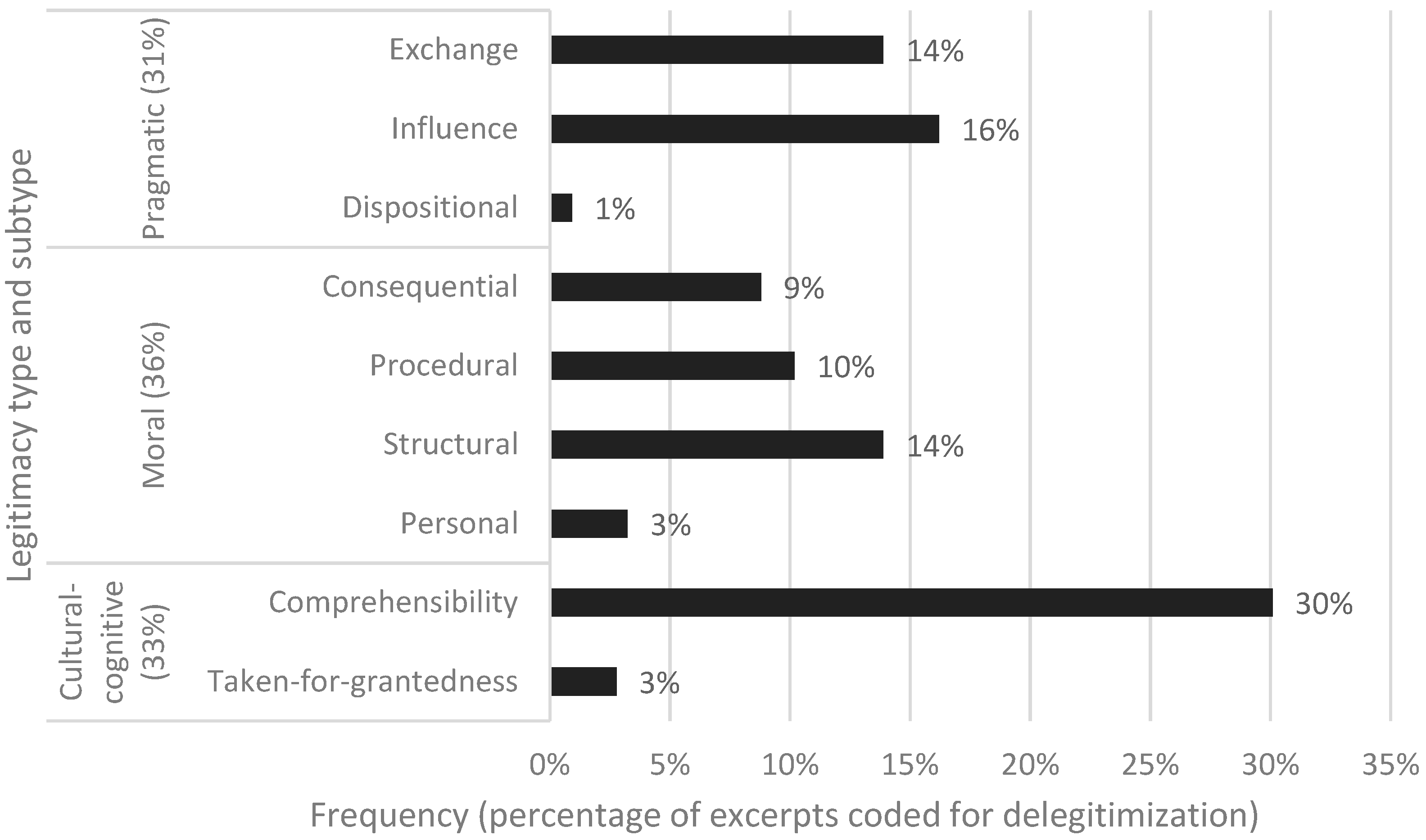

3.1.2. Legitimacy Types

3.2. Preferred Types of Centralized Accommodation

- Sport halls, which have a high percentage of excerpts coded for delegitimization compared to other types.

- Former airports and light-frame structures, which were primarily legitimized with consequential legitimacy, have a low percentage of excerpts coded for delegitimization, and they were primarily described as short-term solutions.

- Buildings with no major renovations (excluding sport halls and airports) and container housing, which were primarily legitimized with comprehensibility and procedural legitimacy and had an intermediate percentage of excerpts coded for delegitimization.

- Modular housing and buildings with major renovations, which were primarily legitimized with consequential legitimacy, had a low frequency of excerpts coded for delegitimization, described as both short and long-term solutions.

- Private apartments within centralized accommodations that were primarily legitimized with procedural and consequential legitimacy, had a low percentage of excerpts coded for delegitimization, and were primarily described as long-term solutions (see Table 3 for detailed excerpt frequencies).

4. Discussion

4.1. Strategies for Informed and Satisfactory Decision-Making

4.2. Choosing Adequate Types of Centralized Accommodation

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

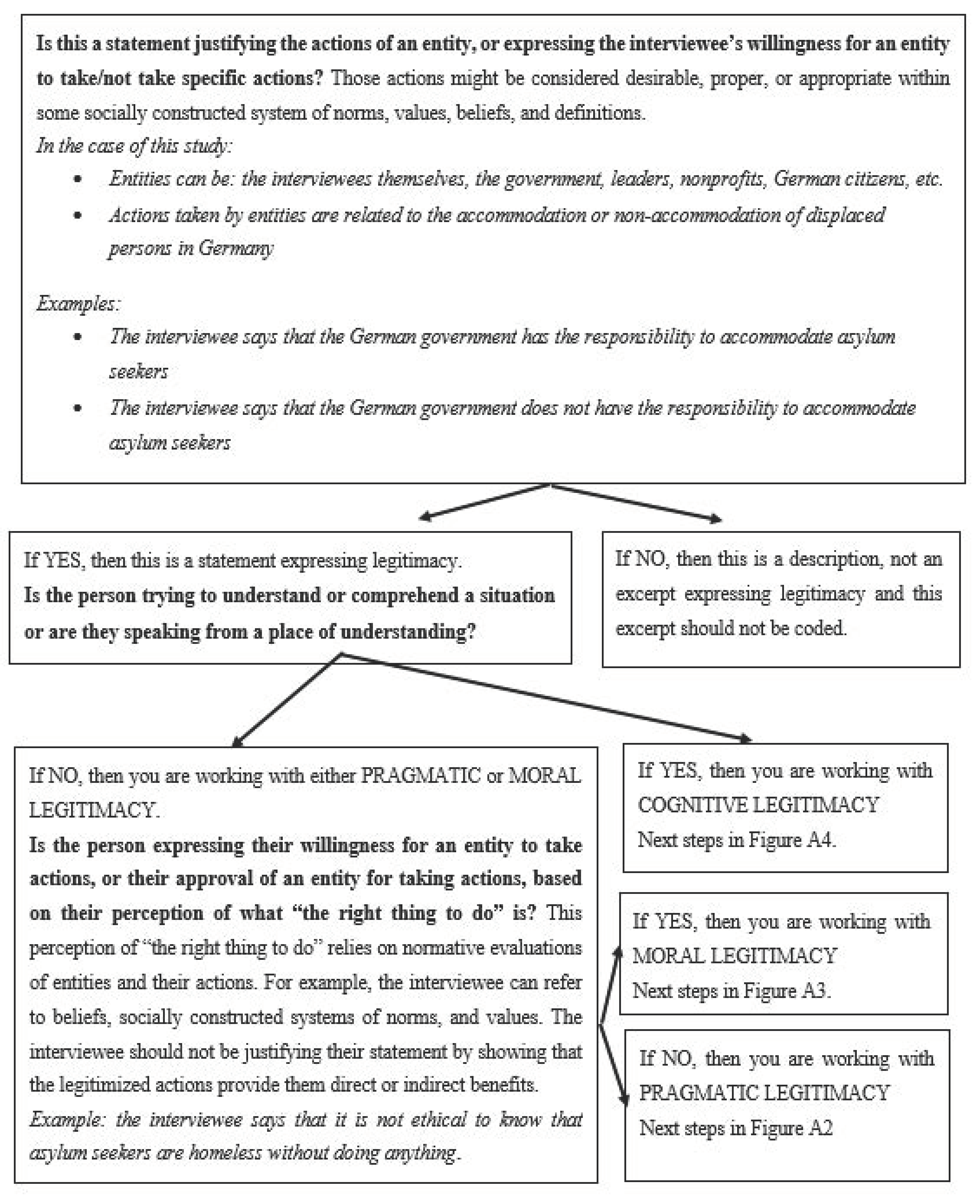

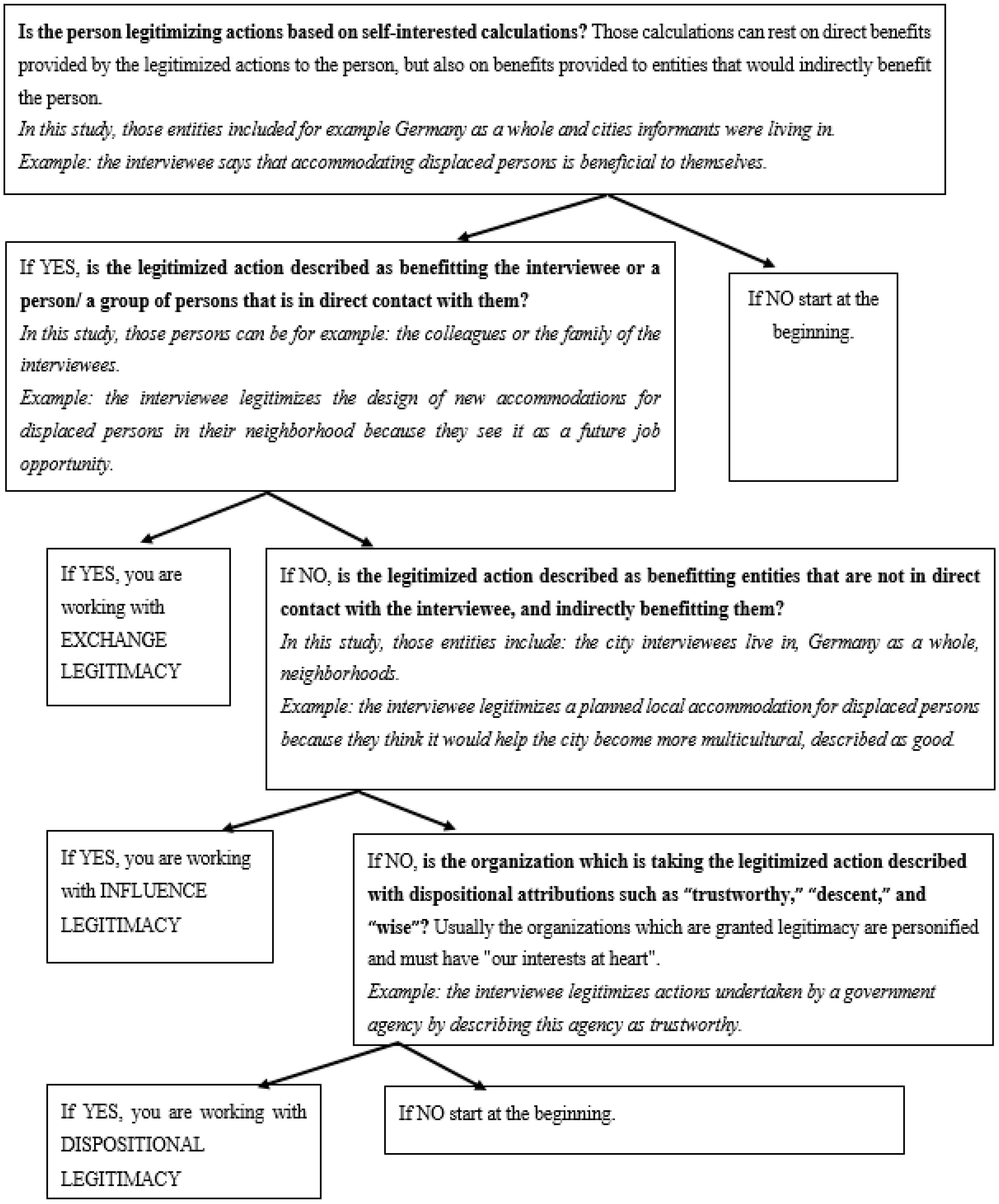

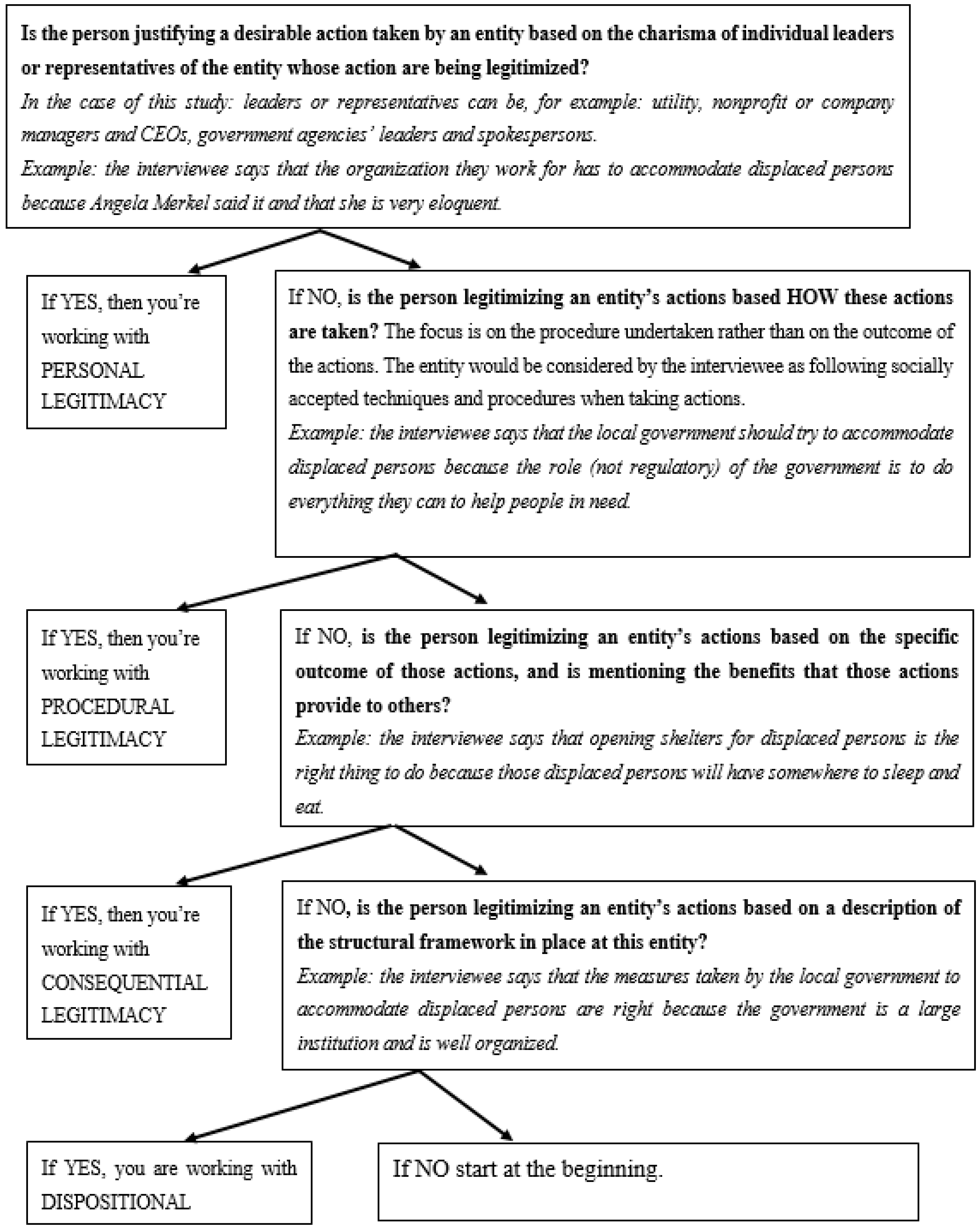

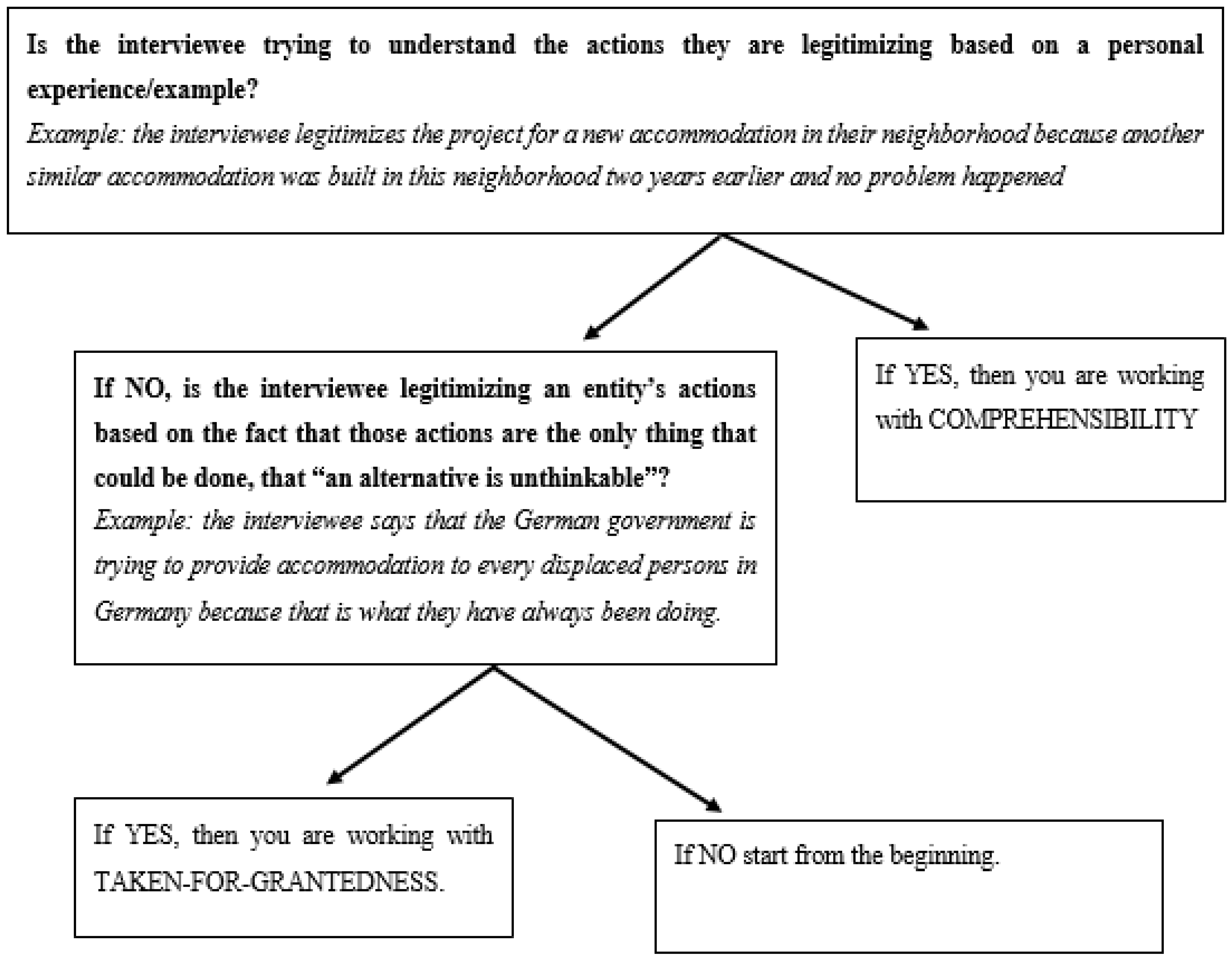

Appendix A

| Legitimacy Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Pragmatic legitimacy | Relies on self-interested calculations of the most immediate audiences of the organization that is being legitimized; usually rests on direct interactions between audience and organization, but can also rest on “broader political, economic or social interdependencies”. |

| Subtype: Exchange legitimacy | Represents a “support for an organizational policy based on that policy’s expected value to a particular set of constituents.” For this study’s purpose, this “particular set of constituents” was chosen to be informants or persons in direct contact with them (e.g., their family). |

| Subtype: Influence legitimacy | Represents the social aspect of pragmatic legitimacy and is a support for an organization because the informants “see it as being responsive to their largest interest”. |

| Subtype: Dispositional legitimacy | Is used when informants “react as though organizations were individuals,” and legitimize their actions with dispositional attributions (e.g., organizations are trustworthy, wise). |

| Moral legitimacy | Evaluates whether an activity is the “right thing to do” by assessing the possible benefits of the action to societal welfare based on a socially constructed value system. |

| Subtype: Consequential legitimacy | Judges organizations based on their accomplishments. |

| Subtype: Procedural legitimacy | Judges organizations based on their techniques and procedures. |

| Subtype: Structural legitimacy | Judges organizations based on their structural characteristics. For example, informants can legitimize an agency’s actions because this agency is well experienced. |

| Subtype: Personal legitimacy | “Rests on the charisma of individual organizations leaders”. |

| Cognitive legitimacy | Considers “what is understandable” unlike pragmatic and moral legitimacies that rely on “what is desirable.” Cognitive legitimacy is based on taken-for-granted cultural and personal accounts. |

| Subtype: Comprehensibility | Uses informants’ daily experiences and larger beliefs systems to legitimize an action by simply understanding it. |

| Subtype: Taken-for-grantedness | Used when informants automatically legitimize actions because an alternative is unthinkable for them. |

Appendix B. Legitimacy Coding Method for Investigators

References

- UNHCR. Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2018. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/en-us/statistics/unhcrstats/5d08d7ee7/unhcr-global-trends-2018.html (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Edwards, A. Global Forced Displacement Tops 70 million. 19 June 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2019/6/5d08b6614/global-forced-displacement-tops-70-million.html (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- UNHCR. Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2017. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- IDMC. Global Internal Displacement Database. 2019. Available online: http://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/201710-IDMC-Global-disaster-displacement-risk.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Sandri, E. ‘Volunteer Humanitarianism’: Volunteers and humanitarian aid in the Jungle refugee camp of Calais. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 44, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.M.; Castañeda, H. Representing the “European refugee crisis” in Germany and beyond: Deservingness and difference, life and death. Am. Ethnol. 2016, 43, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hacker, M.E.; Kaminsky, J.; Faust, K.M. Legitimizing Involvement in Emergency Accommodations: Water and Wastewater Utility Perspectives. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, J.C.; Faust, K.M.; Kaminsky, J. Legitimization of the Inclusion of Cultural Practices in the Planning of Water and Sanitation Services for Displaced Persons. Water 2019, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli Gattinara, P. The ‘refugee crisis’ in Italy as a crisis of legitimacy. Contemp. Ital. Politics 2017, 9, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman Mark, C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faure, J.C.; Faust, K.M.; Kaminsky, J. Rapid Population Increase and Urban Housing Systems: Legitimization of Centralized Emergency Accommodations for Displaced Persons. Working Paper Series. In Proceedings of the EPOC-MW Conference, Engineering Project Organization Society, Fallen Leaf Lake, CA, USA, 5–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. News Release 4 March 2016. Asylum in the EU Member States Record Number of Over 1.2 Million First Time Asylum Seekers Registered in 2015 Syrians, Afghans and Iraqis: Top Citizenships. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-is-new/news/news/2016/20160304_1_en (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- BBC News. Germany Migrant Bus Surrounded by Protesters. 2016. Available online: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35616834 (accessed on 4 May 2019).

- The Guardian. “Tensions Rise in Germany over Handling of Mass Sexual Assaults in Cologne | World News | The Guardian”. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jan/06/tensions-rise-in-germany-over-handling-of-mass-sexual-assaults-in-cologne (accessed on 5 May 2018).

- The Telegraph. Reuters, and Agence France-Presse. Left-Wing Protesters Clash with German Police before Right-Wing AfD Congress. Available online: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/04/30/left-wing-protesters-clash-with-german-police-before-right-wing/ (accessed on 17 April 2017).

- BAMF—Bundesamt Für Migration Und Flüchtlinge—Initial Distribution of Asylum-Seekers. Available online: http://www.bamf.de/EN/Fluechtlingsschutz/AblaufAsylv/Erstverteilung/erstverteilung-node.html (accessed on 9 April 2018).

- Hamann, U.; El-Kayed, N. Refugees’ Access to Housing and Residency in German Cities: Internal Border Regimes and Their Local Variations. Soc. Incl. 2018, 6, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Soederberg, S. Governing Global Displacement in Austerity Urbanism: The Case of Berlin’s Refugee Housing Crisis. Dev. Chang. 2019, 50, 923–947. [Google Scholar]

- Housing—Berlin.de. Available online: https://www.berlin.de/fluechtlinge/en/information-for-refugees/housing/ (accessed on 8 April 2018).

- Al-Husban, M.; Adams, C. Sustainable refugee migration: A rethink towards a positive capability approach. Sustainability 2016, 8, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nammari, F. Participatory urban upgrading and power: Lessons learnt from a pilot project in Jordan. Habitat Int. 2013, 39, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthmann, J.-P.; Hilde, K.; Delia, B.; Nuha, H.; Loretxu, P.; Jacques-Yves, N.; Mercedes, T.; Diaz, F.; Moren, A.; Grais, R.F.; et al. A Large Outbreak of Hepatitis E among a Displaced Population in Darfur, Sudan, 2004: The Role of Water Treatment Methods. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toole, M.J.; Waldman, R.J. The Public Health Aspects of Complex Emergencies and Refugee Situations”. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1997, 18, 283–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.M.; Esnard, A.M.; Sapat, A. Hurricane events, population displacement, and sheltering provision in the United States. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2011, 13, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.N.; Ann-Margaret, E.; Alka, S. Population Displacement and Housing Dilemmas Due to Catastrophic Disasters. J. Plan. Lit. 2007, 22, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.L.; Valerie, M. Natural Disasters and Population Mobility in Bangladesh. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6000–6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterett, S.M. Need and citizenship after disaster. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2011, 13, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozdilsky, J.L. Second hazards assessment and sustainable hazards mitigation: Disaster recovery on Montserrat. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2001, 2, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizarralde, G.; Johnson, C.; Davidson, C. Rebuilding After Disasters: From Emergency to Sustainability; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Félix, D.; Branco, J.M.; Feio, A. Temporary housing after disasters: A state of the art survey. Habitat Int. 2013, 40, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Tu, Y. An Evaluation of the Paired Assistance to Disaster-Affected Areas Program in Disaster Recovery: The Case of the Wenchuan Earthquake. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D. The housing situation of refugees in Montreal three years after arrival: The case of asylum seekers who obtained permanent residence. J. Int. Migr. Integr. /Rev. l’integration Migr. Int. 2001, 2, 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. ‘The suffering is too great’: Urban internally displaced persons in the Casamance conflict, Senegal. J. Refug. Stud. 2007, 20, 60–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, E.; Lee, K.; Moonilal, V.; Pereira, K. Potential of geographic information systems for refugee crisis: Syrian refugee relocation in urban habitats. Habitat Int. 2018, 72, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bris, P.; Bendito, F. Lessons Learned from the Failed Spanish Refugee System: For the Recovery of Sustainable Public Policies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Maitland, C.; Tomaszewski, B. Promoting participatory community building in refugee camps with mapping technology. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, Singapore, 15–18 May 2015; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, C. Underorganized interorganizational domains: The case of refugee systems. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 1994, 30, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, L.R., III; Omar, M.; Farid, A.M. An integrated QFD and axiomatic design methodology for the satisfaction of temporary housing stakeholders. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Axiomatic Design, Campus de Caparica, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–26 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R. Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2006, 57, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, A.; McConnell, F.; Wilson, A. Understanding legitimacy: Perspectives from anomalous geopolitical spaces. Geoforum 2015, 66, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, J.; Jeffrey, P. Organizational Legitimacy: Social Values and Organizational Behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.M.; Walker, H.A.; Zelditch, M. Legitimacy and Collective Action. Soc. Forces 1986, 65, 378–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaven, S.; Wilson, T.; Johnston, L.; Johnston, D.; Smith, R. Role of boundary organization after a disaster: New Zealand’s natural hazards research platform and the 2010–2011 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2016, 18, 05016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, N.; Woodsong, C.; MacQueen, K.; Guest, G.; Namey, M. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector’s Field Guide; Family Health International: Durham, NC, USA, 2005; Available online: http://repository.umpwr.ac.id:8080/bitstream/handle/123456789/3721/Qualitative%20Research%20Methods_Mack%20et%20al_05.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 18 February 2019).

- Baxter, J.; Eyles, J. Evaluating qualitative research in social geography: Establishing ‘rigour’in interview analysis. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1997, 22, 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihas, P. Qualitative Data Analysis; Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Storbjörk, S.; Hjerpe, M.; Glaas, E. “Take It or Leave It”: From Collaborative to Regulative Developer Dialogues in Six Swedish Municipalities Aiming to Climate-Proof Urban Planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantsperger, M.; Thees, H.; Eckert, C. Local Participation in Tourism Development—Roles of Non-Tourism Related Residents of the Alpine Destination Bad Reichenhall. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehling, S.; Kolleck, N. Cross-Sector Collaboration in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs): A Critical Analysis of an Urban Sustainability Development Program. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spradley, J.P. The Ethnographic Interview; Holt, Rinehart and Winston: Boston, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, H.L. The second step in data analysis: Coding qualitative research data. J. Soc. Health Diabetes 2015, 3, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, F.; Faust, K.M.; Kaminsky, J.A. Public perceptions from hosting communities: The impact of displaced persons on critical infrastructure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ayllón, S. New Strategies to Improve Co-Management in Enclosed Coastal Seas and Wetlands Subjected to Complex Environments: Socio-Economic Analysis Applied to an International Recovery Success Case Study after an Environmental Crisis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-Valdivieso, F.; Saraite-Sariene, L.; Alonso-Cañadas, J.; Caba-Pérez, M.D.C. Do Corporate Carbon Policies Enhance Legitimacy? A Social Media Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Sánchez, F.S.; Reinoso-Bellido, R.; Abarca-Álvarez, F.J. Sustainable Environmental Strategies for Shrinking Cities Based on Processing Successful Case Studies Facing Decline Using a Decision-Support System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacin, M.T.; Oliver, C.; Roy, J.P. The legitimacy of strategic alliances: An institutional perspective. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suddaby, R.; Bitektine, A.; Haack, P. Legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 451–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renn, O. Risk Governance: Coping with Uncertainty in a Complex World; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bitektine, A. Toward a theory of social judgments of organizations: The case of legitimacy, reputation, and status. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2011, 36, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L.; Bundy, J.; Tost, L.P.; Suchman, M.C. Organizational legitimacy: Six key questions. SAGE Handb. Organ. Inst. 2017, 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCRC. Home|Dedoose. Available online: http://www.dedoose.com/ (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Singleton, R.A., Jr.; Straits, B.C.; Straits, M.M. Approaches to Social Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LeBreton, J.M.; Jenell, L.S. Answers to 20 Questions about Interrater Reliability and Interrater Agreement. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 815–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonj, C.; Diekkrüger, B.; Borgemeister, C.; Kistemann, T. Health risk perceptions and local knowledge of water-related infectious disease exposure among Kenyan wetland communities. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2019, 222, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Cultural Dimensions in Management and Planning. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 1984, 1, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abowitz, D.A.; Toole, T.M. Mixed method research: Fundamental issues of design, validity, and reliability in construction research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 136, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.N. Where Do People Go? Camp Fire Makes California’s Housing Crisis Worse. Los Angeles Times. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-paradise-housing-shortage-20181123-story.html (accessed on 4 November 2019).

| Accommodation Denomination | Types of Accommodations Provided to Displaced Persons |

|---|---|

| Initial reception facilities and collective accommodations [20] | Various types of buildings owned or rented by the government, including:

|

| Emergency accommodations [20] | Short-term solutions—intended for a few months—to prevent displaced persons from being homeless in Germany. They typically were:

|

| Responsibility | Organization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture Company | Other Company | Nonprofit | Government Agency | Utility | |

| Advising role for accommodation locations | - | 2 | 2 | - | 1 |

| Urban planning | 2 | 1 | - | 6 | - |

| Permitting | - | - | - | 2 | - |

| Design of accommodations | 7 | - | - | - | - |

| Construction and renovation | - | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| Type | Frequency of Legitimacy Excerpts (i.e., Legitimization or Delegitimization) | Percentage of Legitimacy Excerpts Coded for Delegitimization (as Opposed to Legitimization) | Predominant Legitimacy Subtype for Legitimizing Accommodation Type | Frequency of Timeframe Excerpts (i.e., Long- or Short-Term Solutions) | Percentage of Timeframe Excerpts Coded for Short-Term Solution (as Opposed to Long-Term Solutions) | Select Stakeholder Justifications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport halls | 34 | 47% | No predominant type | 23 | 4% | No privacy Bad livability |

| Former airports | 34 | 14% | Consequential (31%) Comprehensibility (24%) | 20 | 15% | Expensive Mixed views on the livability Unnecessary |

| Light-frame structures | 74 | 24% | Consequential (29%) Procedural (21%) | 42 | 7% | Expensive Unnecessary |

| Buildings with no major renovations, excluding sport halls and airports | 50 | 28% | Comprehensibility (31%) Procedural (28%) | 35 | 6% | Good livability |

| Container housing | 46 | 35% | Procedural (37%) Comprehensibility (23%) Consequential (23%) | 21 | 14% | Expensive Mixed views on the livability Unnecessary |

| Modular housing | 63 | 11% | Consequential (27%) Comprehensibility (21%) Influence (16%) Procedural (16%) | 29 | 31% | Good livability Possibly used by students after crisis Cannot be used by Germans |

| Buildings with major renovations | 87 | 15% | Consequential (27%) Procedural (20%) | 27 | 33% | Good livability |

| Private apartments in centralized accommodations | 45 | 13% | Procedural (28%) Consequential (26%) | 13 | 85% | Good livability |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faure, J.C.; Faust, K.M.; Kaminsky, J. Stakeholder Legitimization of the Provision of Emergency Centralized Accommodations to Displaced Persons. Sustainability 2020, 12, 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010284

Faure JC, Faust KM, Kaminsky J. Stakeholder Legitimization of the Provision of Emergency Centralized Accommodations to Displaced Persons. Sustainability. 2020; 12(1):284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010284

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaure, Julie C., Kasey M. Faust, and Jessica Kaminsky. 2020. "Stakeholder Legitimization of the Provision of Emergency Centralized Accommodations to Displaced Persons" Sustainability 12, no. 1: 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010284

APA StyleFaure, J. C., Faust, K. M., & Kaminsky, J. (2020). Stakeholder Legitimization of the Provision of Emergency Centralized Accommodations to Displaced Persons. Sustainability, 12(1), 284. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010284