Abstract

Despite a rising amount of urban shrinkage research, little attention is paid to the shrinking historic ethnic neighborhoods, where authenticity plays a vital role in maintaining local heritage, identity, and livability. This article concerns the historic Chinatowns in the United States that are largely confronting the evident decline of the ethnic Chinese population and authenticity dilution. Taking San Francisco’s historic Chinatown as a case study, the research portrays an alternative face of urban shrinkage at the neighborhood level with a specific integration of authenticity discourse. Through combining quantitative statistical analysis and qualitative research on the basis of interviews, the paper presents how neighborhood shrinkage and authenticity dilution are perceived and characterized and further reveals the interactive process of neighborhood shrinkage and authenticity dilution, and their impacts on social sustainability. The study also demonstrates the notable necessity and possibility to incorporate the issue of authenticity into the discourse of urban shrinkage, which enables a deepened understanding of the cumulative effects of urban shrinkage on local lives and social sustainability, and establishing a more comprehensive and targeted framework of strategies, particularly for those carrying significant social, cultural, and emotional meaning.

1. Introduction

Urban shrinkage, also expressed as “urban decline,” is a multifaceted, multidimensional, multi-scalar, and multitemporal phenomenon encompassing worldwide regions, cities, metropolitan areas, and neighborhoods [1,2,3,4]. Rich evidence suggests shrinking regions, cities, areas, and neighborhoods have more difficulty in achieving sustainability [5,6,7,8]. The issue of sustainability frequently involves economic, environmental, and social dimensions, among which, the social component has been the least contextualized and has not been very clearly defined or agreed upon to date [6,9]. In order to understand and maintain social sustainability in the shrinking urban context, the understanding of citizens’ perception of shrinkage and other associated social changes are paramount but frequently overlooked [6,10].

Urban shrinkage has mainly been documented by scholars through identifying causes of shrinkage and decline [11,12]; describing influences on physical spatial planning and land use [13,14], socio-spatial segregation [15,16], and economical [17], and environmental aspects [18]; discussing planning, policy, and governance responses [4,19,20,21,22,23]; and classifying and comparing trajectories of urban shrinkage in different countries, regions, and cities [24,25,26,27,28,29].

In terms of urban shrinkage at the neighborhood level, associated studies mainly concern the spatial and social effects on neighborhood quality [10,30], and the policy responses of community governance and redevelopment [31,32,33,34]. Noticeably, the existing literature does not go far enough in explaining the meaning of neighborhood shrinkage for local residents, particularly regarding the aspects of local identity and place attachment. Additionally, studies of neighborhood decline have mainly focused on the post-industrial and post-socialist contexts. Little attention is paid to shrinking historic neighborhoods, let alone the shrinking historic ethnic neighborhoods, where challenges of cultural inheritance, identity construction, heritage protection, livability improvement, and the redevelopment of local traditional business are confronted, and authenticity plays a vital role in maintaining local heritage, identity, and livability. Typical cases include many historic Chinatowns in the United States.

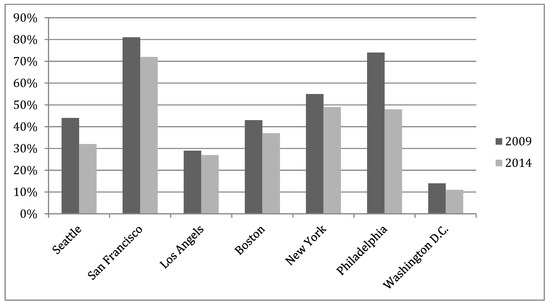

Compared with other old immigrant enclaves in big cities of the United States, a larger number of historic Chinatowns survive to date [35] (p. 1). Yet, since the end of the last century, the shrinkage of the ethnic Chinese population, accompanied with social, economic, and cultural changes, has taken place in many historic Chinatowns in the United States, such as San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, etc. [36,37,38]. Increasingly more ethnic Chinese moved out from their former homeland. From 2009 to 2014, the amount of ethnic Chinese in Manhattan’s Chinatown decreased from 47,000 to 38,000; the proportion of ethnic Chinese declined from 81% to 72% in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and from 74% to 48% in Philadelphia; in Washington D.C., the proportion was 11% in 2014, less than 1/10 of the amount in the heyday (Figure 1) [39]. In some downtown Chinatowns in this country, such as in Washington D.C., Providence, Baltimore, and Detroit, the loss of most or all of the ethnic Chinese population occurred [36]. Additionally, some Chinatowns have been deteriorating into a touristic thematic park or ethnic Disneyland, which are referred to “a place that lost authenticity and historic functions as an immigrant gateway and ethnic community” [35] (pp. 2–3). As a result, Chinatowns’ specific living styles, culture, and place attachment that had been developed for over one century are fading away.

Figure 1.

The proportion changes of the ethnic Chinese population in historic Chinatowns in the United States. Source: Authors’ own diagram based on the data from Vocativ [39].

Research on Chinatowns can be dated back to at least the 1950s [40]. Compared with the studies of Chinatowns in Southeast Asian countries, the amount of the research concerning Chinatowns in the United States is evidently less and they mostly concentrate in the history field. Studies of Chinatowns in the United States in the perspectives of urban planning, sociology, and anthropology are quite limited and mainly focus on Chinatowns’ transformation, particularly in terms of sociological, cultural, and economic dimensions [35,37,41,42,43]; the actions and implications of community-based organizations [44,45]; and the formation, development, and integration of new ethnic Chinese settlements [46,47,48].

Following the author’s previous study of the authentic transformation of Chinatowns in the San Francisco Bay Area [49,50], this work taking San Francisco’s historic Chinatown as a case study attempts to link the discourses of neighborhood shrinkage, authenticity dilution, and social sustainability. It aimed at addressing the following research questions: (1) How do inhabitants of shrinking historic ethnic neighborhoods experience shrinkage and authenticity dilution? (2) How do neighborhood shrinkage and authenticity dilution interact and further influence social sustainability? The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature on urban shrinkage, authenticity, and social sustainability, and discusses their potential interactions. Section 3 explains the study area and the methodological approach of this research. Section 4 elucidates upon the quantitative and qualitative research results, particularly through linking the debates of the local peoples’ perception of neighborhood decline and experience of authenticity dilution, and discusses the policy implications and recommendations. The paper ends with a summary of some findings and reflections of the significance and implications of this study, together with recommendations for future research.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Shrinking Cities and Neighborhoods

The contemporary development of worldwide nation states, regions, cities, and localities is characterized as being uneven with the close co-existence of growth and decline [51,52]. A recently growing academic discourse has been developing internationally under the term “regional/urban shrinkage,” which concerns the atypical spatial development that is associated with decline. Despite a lack of a common definition of what shrinkage exactly means in the international debate [23,53], there is a consensus that shrinking regions, cities, parts of cities, metropolitan areas, or towns are experiencing dramatic population decline.

The phenomenon of urban shrinkage is associated with multidimensional causes and consequences, involving economic, demographic, geographic, social, and physical dimensions [1,2,27]. Once urban shrinkage sets in, investment by public and private actors is usually reduced and restricted to the most favorable localities, which implies the decay of infrastructure, deterioration of service, and downgrading of livability and vitality [10,54]. Also, urban shrinkage generally comes with a selective migration process, leaving the most marginalized groups behind [15,16]. The interplay of these effects results in growing socio-spatial disparities and the accompanying inequalities [15].

Shrinkage involves different levels: states, regions, cities, metropolitans, and neighborhoods. Rather than following universal patterns, this phenomenon has specific local or national aspects. For instance, unlike in old industrial regions of Europe, urban shrinkage in the United States usually takes place in urban cores, while suburban regions continue to grow [26] (p. 273). Yet, it should be noted that urban shrinkage can be hardly addressed locally [2,55] since the roots of the causes conventionally lie outside of the area where shrinkage consequences can be observed [31].

Compared with the shrinkage at other levels, the shrinkage at the neighborhood level is more easily perceived by people through outmigration, abandoned buildings, vacant land plots, deteriorated buildings, an increase of poverty and crime, etc. Some scholars define shrinkage at the neighborhood level as “any negative development in the physical, social, or economic conditions of a neighborhood as experienced by its residents or other stakeholders” [55] (p. 4). Perceptions and reactions of local residents are salient in defining whether a neighborhood is shrinking and declining, and can be regarded as a key to considering strategies to tackle neighborhood decline [10].

2.2. Authenticity and Social Sustainability

The word authenticity is originally from Greek and Latin, referring to “authoritative” and “original” [56]. Traditionally, the core meaning of authenticity highlights what is genuine, real, and unique, and is recognized and judged using objective professional techniques and scientific knowledge [57,58]. Presently, the concept of authenticity shifts its focus from early scientific perspective on objects to sociology and anthropology, meaning that “authenticity is no longer a property inherit in an object, but a projection from beliefs, context, ideology or even imagination” [59] (p. 596). Wang suggests distinguishing the authenticity between objects and experiences, and proposes that authentic experiences are from the inner feelings and interpersonal interactions [60]. Based on this, he integrates authentic experiences into personal identity, individuality, and self-realization. Florida characterizes authenticity as “real buildings, real people, and real history,” regarding authenticity as a precondition for “unique and original experiences” [61] (p. 228). Similarly, Zukin deems that a place is authentic if it can create original experiences [62]. Here, “original” does not refer to the earliest group of inhabitants settled in a neighborhood but suggests “a moral right to the city that enables people to put down roots” [62] (p. 6).

Several scholars suggest the close relationship between authenticity and identity of place, and sense of place and belonging [62,63,64,65,66,67]. Here, the concept of authenticity highlights origins and continuity, involving not only local physical, social, economic, and cultural characteristics, but also the people and their lifestyles and perceptions of the place [62,66,67]. For instance, Wesner argues for the linkage between authenticity and identity of place and people’s associated perceptions, indicating that authenticity of place is related to “inherent qualities that ‘belong’ to a place (intrinsic values), such as particular physical characteristics”; meanwhile, authenticity is “a socially-constructed, mutable and time-bound concept conferred upon places and reflecting people’s perceptions, desires, interpretations and identities” [66] (pp. 68, 69). Zukin associates authenticity with sense of place, defining a sense of local authenticity is about a sense of “living local both in the local neighborhood and on the land” [62] (p. 117).

In general, authentic cities and places in most cases enable providing a local authentic feeling, which is “a continuous process of living and working, a gradual build-up of everyday experience, the expectation that neighbors and buildings that are here today will be here tomorrow” [62] (p. 6). Recent studies concerning neighborhood authenticity include case studies of the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham in England [66,67], and Richmond night market in Canada [65]. It is also worth mentioning the earlier but landmark work by Anderson, who shows the re-oriented transformation of Australian Chinatowns generated by the governments’ redevelopment schemes, including some efforts to satisfy the need for authenticity in the appearance and harmonious spiritual significance [68].

Whilst social sustainability is a wide-ranging, multi-dimensional concept that has not been clearly defined, some scholars point out that it is not only about societal qualities, but also about creating social structures to guarantee these qualities for the coming generations [6]. Factors related to authenticity like social networks, neighborhood activities, identity of place, and sense of place and belonging are widely deemed crucial for maintaining social sustainability [6,9,69].

2.3. Shrinking Neighborhoods, Authenticity, and Social Sustainability

Declining authentic neighborhoods usually face problems like indigenous population decline, functional displacement, and accompanying physical and social changes. Many of these problems produce negative impacts on maintaining the authenticity and social sustainability of shrinking neighborhoods [6,69]. The dilution of authenticity is likely to result in the decrease of the neighborhood’s livability, attractiveness, vitality, and sense of belonging [62], and would accelerate the decline. Such a vicious circle may suggest the need to integrate the discourses of shrinkage and authenticity dilution, since both discourses with possible shared causes from gentrification and globalization matter to the quality of local lives and each neighborhood’s social sustainability. Given that citizens are directly involved in urban shrinkage and authenticity dilution, their perceptions and reactions are vital to maintaining the social sustainability of declining neighborhoods [6].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

As the largest Chinatown outside of Asia and the oldest in North America, the historic Chinatown of San Francisco is regarded as the “unofficial capital of Chinese America” and the place “where the first Chinese America institutions—social, economic, cultural, political—were formed” [45] (p. 13). It was initially formed during 1848 and 1849, when the male contract laborers from Chinese provinces near Pearl River Delta, particularly from Canton, arrived in California in search of wealth during the Gold Rush [45,70]. Chinatown appears in the early official map of San Francisco in 1885 (Figure 2). During the 1880s to the 1900s, a series of discriminatory policies directed at Chinese immigrants, such as the 1882 Federal Chinese Exclusion Act, were issued, leading to an isolated and self-sufficient ethnic community (Figure 2). The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the accompanying fire destroyed much of the city, including Chinatown. Afterward, the local municipality and some Chinese business leaders took the chance to rebuild Chinatown with pagodas, dragon sculptures, and other Chinese architectural elements to reshape the image and attract tourists [43]. Nearly all buildings in the present Chinatown were built at this period. In 1965, the new immigrant act was repealed, replacing the 1943 Chinese Exclusion Act and triggering a high tide of immigration. The number of immigrants further increased after China adopted the economic reform in 1978, which resulted in adjacent neighborhoods gradually becoming home to many ethnic Chinese families, businesses, and institutions [38].

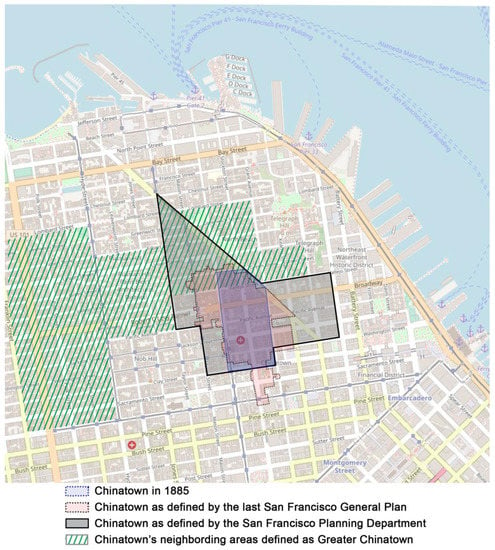

Figure 2.

Chinatown boundaries. Source: Authors’ own diagram based on the data from [71,72,73,74] and the basis map from [75].

Currently, San Francisco’s Chinatown is situated at the core of the city with close proximity to the Financial District and Downtown. Because of its great location, it has been enduring pressures of land re-development and speculation, and confronting a series of challenges like increasing land price and rent, a struggling business climate, crowded and living conditions, the lack of facilities and services (e.g., parking areas, elevators, fire evacuation routes, property management, etc.), and rapid touristic development. For instance, Chinatown has the most overcrowded urban environment in the nation west of Manhattan [45]. As a result, more and more ethnic Chinese have moved out and San Francisco’s Chinatown has been trapped in the dilemma of neighborhood decline and the dilution of authenticity.

It is worth noting that the Chinatown boundaries are not fixed and are defined differently by the local documents and statistics (Figure 2). The territory of Chinatown defined in the last San Francisco General Plan covers a relatively small land area of approximately 30 city blocks and includes census block groups 113 and 118 (Figure 2). Referring to the statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau [71] and the report of the American Community Survey 2012–2016 [72], this study uses the Chinatown’s geographic boundaries defined by the San Francisco Planning Department, covering the census tracts 107, 113, 118, and 611 (Figure 2). Notably, some institutes tend to believe it is significant to recognize some neighboring areas of Chinatown where many Chinese American families are settled [38]. For instance, the Center for Community Innovation of University of California, Berkeley, defines “Greater Chinatown,” covering partial neighboring areas of Russian Hill, Nob Hill, and Polk Gulch, as well as tourist hotspots like North Beach, which is commonly known as Little Italy [38] (Figure 2). Comparing the first historic map with the current diversified definitions of San Francisco’s Chinatown (Figure 2) suggests that Chinatown’s core has almost remained within the same boundaries, yet its general territory has expanded and the evolution of neighboring areas have been deeply influenced by Chinatown.

3.2. Research Method

The study used the case study method and combined quantitative and qualitative research approaches together. The quantitative and qualitative analyses provided evidence to confirm and support each other. The quantitative analysis was based on the data on population dynamics and structure, population income, housing condition, and cost that was collected through the official website of the U.S. Census Bureau Finder [71] and the report of the American Community Survey 2012–2016 [72].

The research drew on an original ethnographic case study, undertaking field observation and qualitative, informal, and semi-structured interviews to capture local people’s perceptions of shrinkage and decline, as well as their authentic and inauthentic experiences in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The field observation was conducted during a research stay from March to September 2016. The interviews were intensively conducted in July and August 2016. Each interview lasted from 20 minutes to 1.5 hours, and there were 30 interviewees in total. The structure of ages and races of interviewees is shown in Table 1. The interviewees included public servants, staff of local community organizations and institutes, volunteers of local community organizations, shopkeepers, and inhabitants living in the neighborhood. Among the participants of this interview, there was one minor. The interviewer obtained the consent of her mother, who was also interviewed. Twenty-seven participants lived in Chinatown when they were interviewed. Other participants had moved out during the last one to three decades, but still worked in Chinatown. Except the minor, all interviews were with individuals. However, on some occasions, these individual interviews became group meetings when other spectators passed by and joined in. Interviews were undertaken either in participants’ workplaces or in the neighborhood’s public spaces. All field observations and interviews were conducted by the same researcher, namely the first author of this article.

Table 1.

The structure of ages and races of interviewees.

During each interview, some general and closed questions about the participant’s age range, occupation, race, length of residence, and household size were asked. Other questions were open-ended and designed to elicit in-depth information, involving participants’ perceptions of the neighborhood decline and authenticity dilution. Three major groups of questions were specifically asked:

- What do you think about the changes of Chinatown, in population, housing costs, living condition, and other aspects? What these changes meant to you?

- In your opinion, what elements are authentic or inauthentic in Chinatown? What elements determine Chinatown’s authenticity or inauthenticity? How have you seen the transformation of authenticity in Chinatown?

- What do you think about the future of Chinatown?

In view of the quite limited education background of most informants, the precise definition of authenticity was not provided during the interview. Interviews were conducted based on participants’ personal understanding, perceptions, and experiences. Only when necessary, for instance, when the respondents asked what authenticity meant or they seemed have some misunderstanding of authenticity, the researcher used the words “original” and “real” to guide informants. Four categories related to the issue of authenticity—built environment, population structure, community function and living condition—were particularly focused upon.

To understand the quantitative characteristics of the shrinkage and associated demographic changes taking place in San Francisco’s Chinatown, theoretical research was conducted including a literature review and quantitative statistical data analysis. The data on population dynamics and structure, population income, housing conditions, and cost were collected and analyzed. The collection was made through the official website of the U.S. Census Bureau Fact Finder [71] and the report of the American Community Survey 2012–2016 [72].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Chinatown Transformations: Population and Housing Dimensions

The statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau showed demographic changes from 2010 to 2017 [71]. For example, the population of San Francisco’s Chinatown decreased from 15,319 to 14,539 (or by 5.1%), and the total number of households declined from 7230 to 6757 (or by 6.5%). The ethnic composition also changed: the share of the Asian people declined from 87.4% to 81.4%, and their absolute number reduced from 13,395 to 11,847. In contrast, during the same period, the proportion of the Asian population increased by 11% in the whole city of San Francisco, where the ethnic Chinese population increased by 7.7%.

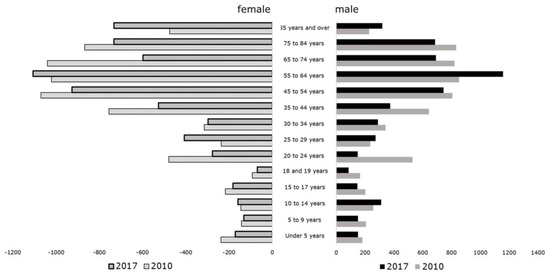

The statistics also presented the difference in the sex and age structure of the Asian population between Chinatown and San Francisco in 2010 and 2017 [72]. The sex structure of the Asian population in Chinatown was characterized by the high proportion of the female population, 53% in both 2010 and 2017, when it was 49% in San Francisco. The age structure of the Asian population in Chinatown was characterized by the high share of elderly people (65 years old and over), about 32% in both 2010 and 2017, and the low share of children (0–17 years old), about 12% in the same years. The share of children was almost the same in San Francisco (about 13%), where the share of the elderly, however, was much lower: about 15% both in 2010 and 2017. Although the general age structure of the Asian population in San Francisco’s Chinatown did not change much from 2010 to 2017, the population declined for most age groups with the exceptions being the 10–14, 25–29, 55–64, and 85 and over age groups (Figure 3). The most evident growth of population was observed in the oldest age group (85 years old and over), with an increase of 50% in 7 years. The report from the American Community Survey 2012–2016 also indicated the difference in the age structure of the Asian population between Chinatown and the entire city from 2012 to 2016 [72]. For instance, the median age of the Asian population in Chinatown was 50.4, while in San Francisco, it was 35; furthermore, Chinatown demonstrated a higher share of households with 60 years and over at 55%, compared to 34% in San Francisco [72]. Although direct statistics about the ethnic Chinese population was not provided, the statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau indicated 93% of the Asian population in Chinatown was the ethnic Chinese in 2017 [71].

Figure 3.

The age–sex structure change of San Francisco Chinatown’s Asian population in 2010 and 2017. Source: Authors’ own diagram based on the data from the U.S. Census Bureau [71].

The report of the American Community Survey 2012–2016 particularly revealed a huge gap of household income between San Francisco and Chinatown during the years from 2012 to 2016 [72]. The median household income in San Francisco was $88,643, while in Chinatown, it was just $21,219. The income per capita in Chinatown was only half of that in San Francisco and the proportion of poverty in Chinatown was 27% compared to 12% in San Francisco. To measure poverty, the American Community Survey uses the standard of poverty thresholds updated by the Census Bureau each year. The poor population is made up of those whose income is lower than the poverty line.

According to the report, whilst the median built year (1957) was almost the same as the one in San Francisco (1958), the qualitative characteristics of housing condition were markedly different during the years from 2012 to 2016 [72]. In San Francisco, the housing structure was dominated by the “single-family house” (32%), while in Chinatown, 56% of houses had “20 housing units or more.” The median size of dwellings in Chinatown was evidently much smaller than average in the city. The largest group of dwellings in San Francisco was two-bedroom apartments (31%), while in Chinatown, it was no-bedroom apartments (47%). Despite a small increase in the share of the apartments with two to three bedrooms from 2010 to 2017, the group of “no bedrooms” apartments’ share became even bigger and the total number of households in Chinatown declined from 7230 to 6757 in the same period (or by 6.5%) [71].

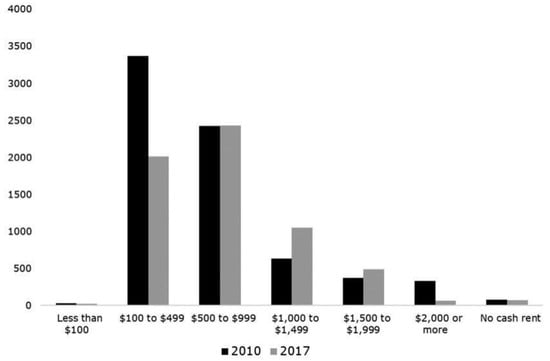

The report suggested the housing prices in Chinatown were largely lower than the city’s average [72]. The median rent in Chinatown was $558, while the city’s average rent was $1190 during the years from 2012 to 2016. Also, the statistics from the U.S. Census Bureau demonstrated a significant change of the structure of monthly housing cost from 2010 to 2017 (Figure 4) [71]. In 2010, the largest group of houses (3366 dwellings or 47% of the total number) was the cheapest group with a monthly cost of $100–$499; the number of dwellings in this category had dropped to 2014 dwellings (by 1352 dwellings or 40.1%), and the proportion of this group was only 33% in 2017. The largest group of dwellings in 2017 was in the category with a monthly cost of $500–$999 (2429 dwellings or 35.6% of the total number). The number of dwellings in this category was almost the same in 2010. The main increase in the absolute number of dwellings was observed in two groups with the monthly cost of $1000–$1499 (by 417 dwellings or 66%) and $1500–$1999 (by 114 dwellings or 30.7%). The share of these two groups in the total amount of dwellings increased from 8.7% in 2010 to 15.5% in 2017, and from 5.1% to 7.2%, respectively. The number of dwellings with a monthly cost from $500 to $999 was relatively stable from 2010 to 2017. Although the decline in the number of dwellings was observed in the group that had the highest monthly cost ($2000 and more), dropping from 330 in 2010 to 63 in 2017 (by 267 units or 80.9%), the overall increase in housing prices from 2010 to 2017 is evident.

Figure 4.

The number of dwellings in the different categories of housing monthly cost in San Francisco’s Chinatown in 2010 and 2017. Source: Authors’ own diagram based on the data from the U.S. Census Bureau [71].

The analysis of Chinatown’s transformation of population and housing dimensions presents a population decline, the replacement of the ethnic Chinese population, disproportionate aging and sex distribution, a high level of poverty, a low quality of the existing housing stock, and a continuously rising housing cost. This indicates negative impacts for the neighborhood’s social sustainability.

4.2. The Perception of Neighborhood Decline and the Experience of Authenticity Dilution: Linking the Debates

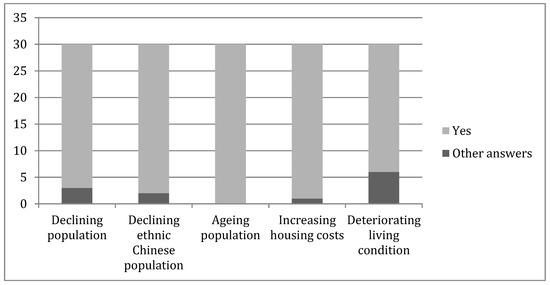

Local people’s perceptions and reactions to the recent changes of San Francisco’s Chinatown in terms of the physical, social, economic, and cultural dimensions were documented through interviews. Figure 5 presents how many interviewees mentioned the key words related to neighborhood decline, including “declining population,” “declining ethnic Chinese population,” “ageing population,” “increasing housing costs,” and “deteriorating living condition,” along with their synonyms. Table 2 summarizes the experiences of authenticity according to the responses to the questions: “What elements are authentic or inauthentic in Chinatown?” and “What elements determine Chinatown’s authenticity or inauthenticity?” Based on the interviews and aforementioned analysis, the study attempted to link the debates concerning neighborhood decline and authenticity dilution through the findings of three prominent interrelated issues that are revealed in the following paragraphs. If necessary, relevant quotes from respondents are used to illustrate the results. To guarantee anonymity, names have been changed.

Figure 5.

The key words mentioned by interviewees associated with neighborhood shrinkage.

Table 2.

The interview summary: The experiences of authenticity. Source: edited from Xie [50].

4.2.1. A Place Called Home with a Deteriorating Image

Compared with many other ethnic groups, the Chinese people may have a stronger sense of family. That was confirmed by some interviewees. For instance, Jones (65–74, staff of the local museum) indicated, “For the Chinese people, family bond is more valued.” According to the interviews, most respondents, particularly the elderly, expressed a strong place attachment and sense of belonging with Chinatown. This rested on the long-term shared history, lifestyles, interests, and values, as well as “accumulated life experiences, friendship, family ties, interpersonal familiarity, joint leisure activities, organized relations,” “daily neighboring relations and mutual support, trust, love and care” [76]. As Chan (75–84, street musician) described, “I have lived here all my life. I like and get used to living in Chinatown. That is because, I think, my whole family has lived here for several decades and we know everything here very well”.

Yet, many informants recognized the deteriorating image of such a home of the ethnic Chinese, including the increasing number of vacant and abandoned buildings, overcrowded and poor living conditions, aging housing stock and infrastructure, drop in security, disappearance of traditional businesses, etc.

“I prefer to the Chinatown in the past, the food, the restaurants, the people, the public spaces, etc. Ten years ago, Chinatown provided cheaper and more diversified goods that attracted many people. In present, big supermarkets and shopping malls located out of Chinatown are more attractive… A lot of houses in Chinatown keep in a state of disrepair for many years with a lack of modern and necessary infrastructure, such as parking areas, sanitary facility, elevators, etc.” (Liang, 35–44, staff of the local community organization).

“Everything becomes worse and unfamiliar. Once there were a lot of good shops and restaurants, but now many of them are closed or moved out, especially big shops and restaurants. … I often went to May Wah Supermarket to buy something in the past, but it was moved out to Clement Street. … Now we are not able to find a restaurant big enough to accommodate large groups of people as before. You know, sometimes we need to invite many friends and family members to have meals together, particularly for wedding or funeral” (Tsu, 55–64, shopkeeper).

“More and more shops and restaurants were closed in recent years, you see, many vacant or abandoned buildings are situated in Chinatown now” (Sumbillo, 35–44, volunteer of the local community organization).

“Even for the survived shops and restaurants, they are closed earlier. That may be attributed to the security problem. More and more homeless people emerge on streets and squares. … After 8 pm, only few pubs and restaurants are still opened. Streets and public spaces are quite empty, except Portsmouth Square. The only several pedestrians are rushed, for instance just passing through Chinatown to the surrounding area—Little Italy. If you walk here after 8 pm, I think you will feel fear” (Chiu, 2–34, shopkeeper).

“Compared with other areas in San Francisco, Chinatown undoubtedly has the worst living environment. In my opinion, the Chinese people who still stay here is because they hardly enable to live outside Chinatown, regarding their quite limited English skills or low economic capability. If they are able, they will move out” (Hallman, 65–74, retired).

“The current living condition is terrible and not good for children. Many people tend to believe children, who grow up in a poor living environment, particularly in single room occupancy, will repeat the past of their parents who were not well educated. I think that’s why my family decided to move out when I was a little boy” (Lau, 25–34, public servant).

Such a deteriorating image is not only the imprinted manifestation of a declining neighborhood, but also poses a threat to the maintenance of the neighborhood authenticity, which was confirmed by interviewees (see “demolished or destructed (historic) buildings/facades/details,” “abandoned (historic) buildings,” “drop of security,” “the homeless,” and “lack of nightlife” summarized in Table 2). As part of the deterioration of the neighborhood, the security problem is crucial since it is fundamental for maintaining authenticity and social sustainability [9,77]. Only when residents feel secure in their neighborhood will social interactions and neighborhood activities take place. Additionally, the displacement of traditional business induced changes in lifestyles, which impaired the maintenance of local authenticity. In sum, neighborhoods with a declining quality and attractiveness often give rise to residents’ negative mental and psychological experiences toward their home [78]. This leads to the loss of collective place attachment and sense of belonging [9,12,22], and generates a detrimental effect on the willingness of people to remain [12]. People might be more inclined to leave a neighborhood with a bad image [21,79]. This, in turn, leads to a lower demand for services and more closure of local stores and restaurants, particularly those that are small in scale, and further disrupts the local social bond and living styles, and erodes local identity, living quality, and attractiveness. Such a vicious circle undermines local social sustainability.

4.2.2. Population Ageing and Outmigration

It is worth noting that when talking about the perception of neighborhood decline, all informants were aware of the problematic phenomenon of population aging and many observed the out-migration of the young population. As Cheung (35–44, staff of the local library) banteringly described, “We always call Chinatowns as ‘old town’. That does not mean the town has a long history, but refer to old people’s town, since more and more young people move out”.

Tse (45–54, public servant) also explained: “Regarding the increasing rent and poor living condition, a lot of young people moved out from Chinatown in past years. You know, they have better English skills and are able to live outside Chinatown. Some families moved out because their young family members found jobs out of Chinatown”.

Neighborhoods affected by depopulation and aging population are very likely to be trapped in a vicious process of multidimensional downgrading, inducing a lower demand for services and a subsequent drop in service efficiency and a further rise in prices [10]. This results in service deterioration and accelerates outmigration, or more precisely, the socially selective out-migration, with the most qualified, educated, and the youngest leaving first [10,15]. The remaining considerable elderly population in San Francisco’s Chinatown confirms this. As a result, the willingness to improve the neighborhood living condition, service, and infrastructure, and remaining in the neighborhood is weakened, which intensifies the outmigration. Additionally, as Table 2 shows, the old generation and their living styles play a paramount role in maintaining the neighborhood’s authenticity. Some informants raised their concerns about the future of Chinatown, as Yu (over 85, shopkeeper) noted: “When elderly people leave in future, how Chinatown would be?”

4.2.3. Gentrification and Disneyfication

In recent decades, when aiming at improving the image of San Francisco Chinatown and attracting elites and tourists, the local municipality encouraged real estate developers to establish upscale dwellings, hotels, chain stores, etc. This induced soaring rents and created gentrified areas. Many areas along the main streets have been deteriorating into a crowded and expensive touristic thematic park or ethnic Disneyland, where it is quite difficult to find local inhabitants and their traditional community life. In fact, local residents have been suffering cultural, social, and economic displacement, and the dilution of place attachment. As the main segment of San Francisco’s Chinatown population, the poor and the elderly particularly face eviction. The invasion of growing gentrification and tourism was observed by interviewees (Table 2), who expressed the struggle and strain when finding an affordable place to live in and in maintaining local traditional business and living styles. As Yue (45–54, shopkeeper) described, “Everything is becoming expensive, especially the rent. In the past, the business worked for the local; but now, they more care about tourists and rich people”.

Yang (55–64, shopkeeper) also pointed out, “Many streets and spaces in Chinatown have become touristic attraction. Streets and alleys are the same but the business is different. A lot of traditional stores are substituted by souvenir shops for tourists, especially along Grant Ave. Stockton St. is the only main street that is not changed a lot”.

Seemingly, Chinatown has become more prosperous and famous, and physical Chinese-style features were maintained, particularly in and around several main streets. Yet, a closer examination, particularly referring to inhabitants’ perceptions, reveals that beneath the surface, the crowded streets and most remaining historic buildings simply provide empty shells for souvenirs and dining. Besides, according to the author’s field investigation, most local touristic business is quite homogenous and insufficiently represents local history and culture. This may explain why many tourists arriving with great expectations depart greatly disappointed with few coming back. Worse still, the wellbeing of a vulnerable population is sacrificed. Along with the displacement of local businesses, residents’ daily lives, social bonds, and sense of belonging are interrupted, which leads to authenticity fading away and further generates a detrimental effect on social sustainability.

4.3. Discussion: Policy Implications and Recommendations

To sum up, the results of the field observation and interviews confirmed the results of the theoretical research including statistical data analysis and the literature review. Despite the general inadequate understanding of urban shrinkage and authenticity, respondents noticed the negative transformations of their neighborhood related to shrinkage and authenticity dilution, and expressed anxiety regarding the destruction of their shared cultural and spiritual home and everyday lives.

Chinatown has always been one of the poorest and overpopulated neighborhoods of San Francisco. One may question whether the decrease of Chinatown’s population would provide more space for the remaining population and improve people’s living conditions. Yet, a closer examination revealed that the population decline of San Francisco’s Chinatown hardly improved its overcrowded living environment. The aforementioned data showed that although the total number of apartments decreased, the share of the no-bedroom apartments grew. This, to some extent, may suggest the general increase of poverty. Besides, according to the interviews, when inhabitants and families became more affluent, mainly due to the better-educated young family members, they usually move out from Chinatown without hesitation, which leads to the persistence of poverty for those that remain. The perception of respondents also provided evidence of the poverty increase and deterioration of living conditions. Also, it is worth noting that although according to the interviews (Table 2), the authentic experiences involved a high-density community and narrow streets. Few informants complained about the poor living condition in the past. This may be attributed to the strong economic, social, cultural, and emotional support provided by Chinatown in the past to its inhabitants. People tolerated an uncomfortable living environment but were afforded opportunities. Presently, the support has become weaker and the role of Chinatown as a self-sustainable community is declining with the simultaneous deterioration of livability. Both ethnographic and theoretical research demonstrated that the remaining population in Chinatown is the most vulnerable, particularly consisting of elderly people and those lacking language skills, whose share is growing. Evidently, this population group will hardly contribute to any further possible assimilation and prosperity of the neighborhood. More importantly, neither poverty nor poor living conditions was thought to represent authenticity of the neighborhood. Chinatown’s unique physical, social, economic, and cultural model that has lasted for several generations is the nucleus of its authenticity. This model provides opportunities to maintain the neighborhood as a highly special component of the urban mosaic of San Francisco. The transformation is inevitable and is a natural consequence of the interplay of multiple factors and processes lying at different levels, from local to global. Accordingly, Chinatown should seek an alternative model to maintain authenticity and enforce the neighborhood’s social sustainability.

To address the aforementioned problems emerging in San Francisco’s Chinatown, some programs have been developed by the Chinatown Community Development Center (a non-profit community organization, simplified to CCDC) in recent years targeted toward the young and aiming at linking them psychologically to the context and the elderly, for instance, the Chinatown Alleyway Tours. The program of the tour is non-profit, youth-run, and youth-led. Guided by high school students who grew up in Chinatown, the tour aims at taking visitors to experience and understand Chinatown’s rich history and present daily lives that are inherited from the past. As Kwok (15–24, student volunteer and tour guide) told the author, “In the past, I was ashamed to let my friends know I was born and grew up in Chinatown. However, since joining this program, I better understood the history, culture and spirit of Chinatown and elderly generations. Now, I am very proud as a member of this neighborhood”.

Wong (15–24, student volunteer) specified another program organized by CCDC: “We have a program called Youth for Single Room Occupancy, aiming at caring about the people living in single room occupancy. Each month, young volunteers, like me, will teach those people something, like how to survive in earthquakes, and how to use Internet and some simple software. … We also organize some activities to enrich the seniors’ lives and help parents to look after their young children”.

During the interview, some participants recognized the efforts of these programs and organizations, and deemed that these efforts had achieved desirable effects, for instance, cultivating the youth’s sense of belonging and responsibility as a member of this ethnic neighborhood, and strengthening the bond between the youth and other groups. Programs like Chinatown Alleyway Tours seemed to create a win-win situation, not only benefiting local inhabitants, but also being conducive to tourism’s sustainable development. Notwithstanding, some informants expressed that they had no idea about the programs organized by CCDC. This suggests the necessity of further mobilization and advocacy.

In general, the local government should be more proactive in mitigating the negative effects of shrinkage and authenticity dilution, rather than leaving it to community organizations and concerned groups. Overall plans and policies with better management to solve the problems regarding public security, neighborhood environment and infrastructure, and transportation access are indispensable, particularly in terms of the need to attract and retain the young population. Policy support from the government for retaining indigenous inhabitants and supporting local traditional business, as well as improving physical living conditions, are necessary. For instance, the government could work with developers and planners to provide more affordable housing. Strong rent control, tenant protections, and new strategies to manage the Ellis Act [80] are crucial. Direct funding support, for example, to pay some of the rent and renovation fees of old buildings, and indirect funding support, such as tax credits and incentives to local business, are recommended. Technical support may include providing some free courses to improve residents’ professional skills, giving advice and instruction regarding redeveloping their traditional business, and inviting professionals to provide building renovation services. In parallel, controlling the proportion of commercial activities that work for tourists and elites, like upscale hotels and restaurants, souvenir shops, and chain stores, is necessary.

Policies and measures for improving health facilities and medical care services are needed, particularly regarding the growing number of elderly. Additionally, creating a child-friendly environment is a wise strategy, for instance, increasing access to educational and cultural facilities, since it can be a decisive motivation for young families to stay in the neighborhood [21]. Toward aiming at improving attractiveness, in particular, for the young population, measures could be taken to exhibit local history, handicraft, music, and art; for instance, introducing more museums, studios, galleries, workshops, and establishing a community center focusing on daily and specific traditional cultural and religious activities to serve both locals and tourists. To organize creative markets in evening, weekends, and holidays is also useful. It is noteworthy that strategies and policies aiming at restoring attractiveness and competitiveness sometimes intensifies gentrification and Disneyfication and is likely to result in social–spatial segregation [15]. Besides, inaction regarding the security problem is likely to result in the local population continuing to depart and the aforementioned strategies and actions being unsuccessful.

Developing publicity and education programs aiming at preaching the significance of maintaining the neighborhood’s culture and spirit make sense. The programs developed by CCDC are worth learning and reconsidering. This must go hand in hand with public policies and measures to support such community organizations, financially and technically, and to encourage participation. As Jacobs indicates, residents who are committed to their neighborhood are less likely to move out [81]. Furthermore, the engagement of local communities and the use of their knowledge and everyday experience are undoubtedly productive toward constructing policies to address negative aspects of shrinkage. A competition, “Shrinking Cities—Reinventing Urbanism,” organized by the Shrinking Cities Project and the magazine archplus in 2004 [82], provides a significant reference that is worthy of critical reconsideration. On the one hand, the competition demonstrates innovative modes of action and ideas to address shrinking cities based on the specific peculiarities of shrinkage, particularly proposing many community-based initiatives. On the other hand, some of these actions and initiatives are narrowly targeted to tackle specific issues of shrinkage and lack a comprehensive framework of strategies and policies. Partial reasons may be attributed to the very minor participation of sociologists, political scientists, and historians, despite the interdisciplinary aim of the competition. Evidently, it is too difficult for the main participants, architects and urban planners, to manage changing economic and political conditions. Besides the involvement of experts in various fields, the policy response of shrinkage is not only about managing shrinkage at the local level, but is embedded in a broader policy framework covering a municipal or a wider geographic area that guides the allocation of resources [20].

5. Conclusions

Focusing on a declining ethnic neighborhood, San Francisco’s historic Chinatown, this study portrays an alternative face of urban shrinkage at the neighborhood level. Through analyzing and evaluating how shrinkage and authenticity dilution are perceived and characterized, this study revealed the interactive process of neighborhood shrinkage and authenticity dilution and their impacts on social sustainability. This study aimed at exploring possible policies and strategies in response to make San Francisco’s historic Chinatown a more livable place that people call home, rather than just a tourist attraction or a historic curiosity.

Residents perceive the San Francisco Chinatown’s transformations in their everyday lives, including population decline and ageing, growing housing costs, deteriorating living conditions, drop in local retail businesses and services, disrupting social bond, and weakening local identity. All of these are features of both neighborhood shrinkage and authenticity dilution of San Francisco’s historic Chinatown. Here, the explanation of authenticity dilution becomes a way to interpret the various and cumulative effects of urban shrinkage on local lives and social sustainability. Such impacts have received insufficient attention in the academic discussion regarding urban shrinkage to date. Moreover, incorporating the issue of authenticity into the discourse of neighborhood decline is likely to establish a more comprehensive and targeted framework of strategies involving physical, social, economic, and cultural dimensions, particularly for the shrinking neighborhoods carrying significant social, cultural, and emotional meaning.

From the theoretical and methodological perspectives, the concepts of urban shrinkage, authenticity, and social sustainability are still undertheorized, ambiguous, and abstract, with a lack of commonly accepted definitions or consensus on what they are exactly and how they should be measured. Through combining quantitative and qualitative analysis, this study considered urban shrinkage at the neighborhood level, authenticity, and social sustainability, along with their interactive processes using multiple perspectives including urban sociology, anthropology, and urban planning and policy at large.

More research is still required. Given the astonishing plurality and the lack of generally applicable solutions of urban shrinkage, developing more case studies and inter-urban and cross-national comparison in various contexts makes sense. The linkage between urban shrinkage, authenticity dilution, and social sustainability, and the associated people’s perceptions are worth further study. Some research questions, for instance, regarding whether neighborhood shrinkage automatically negatively affects the maintenance of authenticity and social sustainability, and whether in some cases, local inhabitants are happy to live in their shrinking neighborhood, deserve to be addressed.

Speaking for historic Chinatowns worldwide, most of them have housed collective memories, a substantial cultural legacy, and a strong sense of bond of the ethnic Chinese, and still play a crucial role in maintaining and promoting social diversification and integration, cultural inheritance, and immigrants’ adaptation to the exotic environment. In essence, Chinatowns’ authenticity is associated with “a transnational ‘space of flows’” that connects them to eastern Asia [65] (p. 548). Currently, authenticity dilution in the wave of gentrification, globalization, and tourism economy, and worse living conditions compared with the city average, can be largely observed in most of the worldwide historic Chinatowns. In order to balance the needs of improving living conditions, preserving authenticity, and developing tourism economy, what authenticity means for historic Chinatowns and what is the reason for maintaining this authenticity merits further research in a more comprehensive, critical, and dynamic way in future. For instance, different generations and groups of the local ethnic Chinese, and other stakeholders have their own understanding and interpretation of the Chinatown’s authenticity, and ideas and expectations of the Chinatown, which calls for more detailed field interviews and categorical discussion in future research. Also, it is necessary to recognize the dynamic nature of authenticity and the political, social, economic, and cultural factors hidden behind the dynamics, such as the transforming local and global ethnic relationship, as well as the potential impacts made by the geopolitical rise of China and its capital and global strategies. Besides, given the more multi-ethnic population of most Chinatowns in present, how to maintain authenticity and local identity, or what it means to be authentic in an age of increasing immigration and more pluralistic society, is worthy of future research.

The growing trend of multi-scalar urban shrinkage worldwide calls for widening the scope of the current urban planning paradigm, from growth-centered to one that integrates growth and decline in pursuit of more sustainable development patterns [2]. Presently, not only Chinatowns, and not only in the United States, many cities and neighborhoods in the world are facing decline, authenticity dilution, and difficulty in achieving sustainability. This study is expected to serve as a starting point to gain a more comprehensive and deeper insight into the diversified manifestation and characteristics of urban shrinkage in various contexts and for multiple levels and dimensions. This could be deemed as a prerequisite to devise tailor-made local strategies and actions, as well as new forms of governance in a more locality-sensitive, concrete, and creative way to improve the quality of life of the remaining population and facilitate social cohesion and sustainable development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.X.; methodology, S.X.; formal analysis, S.X. and E.B.; investigation, S.X. and E.B.; data curation, E.B.; visualization, S.X. and E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.X.; writing—review and editing, S.X. and E.B.; project administration, S.X.; funding acquisition, S.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Research Funds of Huaqiao University, grant number 605-50Y19026.

Acknowledgments

The paper is based on the research by S.X. during her visiting to the Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley. The authors thank the three anonymous peer reviewers and the editors for valuable feedback.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bontje, M.; Musterd, S. Understanding shrinkage in European regions. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großmann, K.; Bontje, M.; Haase, A.; Mykhnenko, V. Shrinking cities: Notes for the further research agenda. Cities 2013, 35, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K.; Wiechman, T.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. Shrinking Cities. International Perspectives and Policy Implications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, D.L.; Shuster, W.D.; Mayer, A.L.; Garmestani, A.S. Sustainability for Shrinking Cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ročak, M.; Hospers, G.-J.; Reverda, N. Searching for Social Sustainability: The Case of the Shrinking City of Heerlen, The Netherlands. Sustainability 2016, 8, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, A.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Runge, J.; Krzysztofik, R.; Dragan, W. Can depopulation create urban sustainability in postindustrial regions? A case from Poland. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slach, O.; Bosák, V.; Krtička, L.; Nováček, A.; Rumpel, P. Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Loopmans, M.; Kesteloot, C. Urban Shrinkage and Everyday Life in Post-Socialist Cities: Living with Diversity in Hrušov, Ostrava, Czech Republic. Built Environ. 2012, 37, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oswalt, P.; Rieniets, T. Atlas of Shrinking Cities; Hatje Cantz Verlag: Ostfildern, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Reckien, D.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. Why do cities shrink? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 1375–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, F.; Haase, D. Does demographic change affect land use patterns? A case study from Germany. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Ma, J. Viewing urban decay from the sky: A multi-scale analysis of residential vacancy in a shrinking U.S. City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 141, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fol, S. Urban shrinkage and socio-spatial disparities: Are the remedies worse than the disease? Built Environ. 2012, 38, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, K.; Haase, A.; Arndt, T.; Cortese, C.; Rumpel, P.; Rink, D.; Slach, O.; Tichá, I.; Violante, A. How urban shrinkage impacts on patterns of socio-spatial segregation: The cases of Leipzig, Ostrava, and Genoa. In Urban Ills: Post Recession Complexities to Urban Living in Global Contexts; Yeakey, C.C., Thompsom, V.L.S., Wells, A., Eds.; Lexington Books: Plymouth, UK, 2013; pp. 241–268. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kempen, R.; Bolt, G.; Van Ham, M. Neighborhood decline and the economic crisis: An introduction. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Haase, D. Urban ecology of shrinking cities: An unrecognized opportunity? Nat. Cult. 2008, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M. Partnerships for Demolition: The Governance of Urban Renewal in East Germany’s Shrinking Cities. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 754–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Hasse, A.; Großmann, K.; Cocks, M.; Couch, C.; Cortese, C.; Krzysztofik, R. How dose (n’t) Urban Shrinkage get onto the Agenda? Experiences from Leipzig, Liverpool, Genoa and Bytom. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hospers, G.-J. Policy responses to urban shrinkage: From growth thinking to civic engagement. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1507–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miot, Y. Residential attractiveness as a public policy goal for declining industrial cities: Housing renewal strategies in Mulhouse, Roubaix and Saint-Etienne (France). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 104–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallach, A. What we talk about when we talk about shrinking cities: The ambiguity of discourse and policy response in the United States. Cities 2017, 69, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galjaard, R.; Van Wissen, L.; Van Dam, K. European Regional Population Decline and Policy Responses: Three Case Studies. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekveld, J.J. Time-Space Relations and the Differences between Shrinking Regions. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, T.; Pallagst, K.M. Urban shrinkage in Germany and the USA: A comparison of transformation patterns and local strategies. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haase, A.; Rink, D.; Grossmann, K.; Bernt, M.; Mykhnenko, V. Conceptualizing Urban Shrinkage. Environ. Plan. A 2014, 46, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.W.; Nam, C.W. Shrinking Cities: A Global Perspective; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hasse, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B. Can a City Successfully Shrink? Evidence from Survey Data on Neighborhood Quality. Urban Aff. Rev. 2010, 47, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, P.; Van Beckhoven, E.; Van Kempen, R. The Decline and Rise of Neighbourhoods: The Importance of Neighbourhood Governance. Eur. J. Hous. Policy 2009, 9, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldhoff, T. Shrinking communities in Japan: Community ownership of assets as a development potential for rural Japan? Urban Des. Int. 2013, 18, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahagi, H. The Nagasaki Model of Community Governance: Grassroots Partnership with Local Government. In Shrinking Cities. International Perspectives and Policy Implications; Pallagst, K., Wiechmann, T., Martinez-Fernandez, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 295–324. [Google Scholar]

- Tintěra, J.; Kotval, Z.; Ruus, A.; Tohvri, E. Inadequacies of heritage protection regulations in an era of shrinking communities: A case study of Valga, Estonia. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 2448–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, D.; Blickenderfer, Z. The planned destruction of Chinatowns in the United States and Canada since c. 1900. Plan. Perspect. 2018, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF). Chinatown Then and Now: Gentrification in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia; ALDEF: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Acolin, A.; Vitiello, D. Who owns Chinatown: Neighborhood preservation and change in Boston and Philadelphia. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1690–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montojo, N. Chinatown: Community Organizing Amidst Change in San Francisco’s Chinatown; Center for Community Innovation: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.urbandis placement.org/sites/default/files/Chinatown_final.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2019).

- Vocativ. The Fight for Chinatown. Available online: https://www.vocativ.com/290583/the-fight-for-chinatown/ (accessed on 31 August 2019).

- Lee, R.H. The Chinese in the United States of America; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M. Chinatown: The Socio-Economic Potential of an Urban Enclave; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. Reconstructing Chinatown: Ethnic Enclave, Global Change; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C. Chinatown and Urban Redevelopment: A Spatial Narrative of Race, Identity and Urban Politics 1950-2000. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.A. Assimilation or Isolation? Community-Based Organizations and their Strategies for Redevelopment in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Middle States Geogr. 2001, 34, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, G. Building Community, Chinatown Style. A Half Century of Leadership in San Francisco Chinatown; Jay Schaefer Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W. Anatomy of a New Ethnic Settlement: The Chinese Ethnoburb in Los Angeles. Urban Stud. 1998, 35, 479–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, M.S. The globalization of a panethnopolis: Richmond district as the New Chinatown in San Francisco. GeoJournal 2005, 64, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, C.M.; Phan, M.B. Ethnic enclave reconfiguration: A ‘new’ Chinatown in the making. GeoJournal 2005, 64, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. The dilemma of authenticity in Chinatown’s evolution in the United States through the case of San Francisco Bay Area (in Chinese). New Archit. 2017, 173, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S. Challenges of authenticity: Exploring the social transformation of historic Chinatowns in the United States for sustainable urban redevelopment through the case of San Francisco. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 19th General Assembly & Scientific Symposium, New Delhi, India, 11–15 December 2017; Available online: https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/General_Assemblies/19th_Delhi_2017/19th_GA_Outcomes/Scientific_Symposium_Final_Papers/ST1/43._ICOA_555_Xie_SM.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Global Capitalism: A Theory of Uneven Geographical Development; Verso: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ganser, R.; Piro, R. (Eds.) Parallel Patterns of Shrinking Cities and Urban Growth: Spatial Planning for Sustainable Development of City Regions and Rural Areas; Ashgate: Surrey, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Döringer, S.; Uchiyama, Y.; Penker, M.; Kohsaka, R. A meta-analysis of shrinking cities in Europe and Japan. Towards an integrative research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.; Pallagst, K.; Schwarz, T.; Popper, F. Shrinking cities as an emerging planning paradigm. Prog. Plan. 2009, 72, 223–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zwiers, M.; Bolt, G.; Van Ham, M.; Van Kempen, R. The global financial crisis and neighborhood decline. Urban Geogr. 2016, 37, 664–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilling, L. Sincerity and Authenticity; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- MacCannell, D. Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, Y.; Steiner, C.J. Reconceptualising Object Authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Rethinking Authenticity in Tourism Experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zukin, S. Naked City: The Death and Life of Authentic Urban Places; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ouf, A.M.S. Authenticity and the sense of place in urban design. J. Urban Des. 2001, 6, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jive’n, G.; Larkham, P.J. Sense of place, authenticity and character: A commentary. J. Urban Des. 2003, 8, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie-Sherman, Y.; Hiebert, B. Authenticity with a Bang: Exploring Suburban Culture and Migration Through the New Phenomenon of the Richmond Nigh Market. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 538–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesener, A. ‘This Place Feels Authentic’: Exploring Experiences of Authenticity of Place in Relation to the Urban Built Environment in the Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesener, A. Adopting ‘Things of the Little’: Intangible Cultural Heritage and Experiential Authenticity of Place in the Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. ‘Chinatown re-oriented’: A critical analysis of recent redevelopment schemes in a Melbourne and Sydney Enclave. Aust. Geogr. Stud. 1990, 28, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramley, G.; Power, S. Urban form and social sustainability: The role of density and housing type. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2009, 36, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, C.L. San Francisco’s Chinatown: An Architectural and Urban History. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau/American Fact Finder. 2010–2017 American Community Survey. Available online: https://factfinder.census.gov/ (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- San Francisco Planning Department. Report of American Community Survey 2012–2016. San-Francisco Neighborhoods Socioeconomic Profiles; San Francisco Planning Department: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Library of Congress. Available online: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4364s.ct002129/?r=-0.006,0.518,0.214,0.13,0l (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- San Francisco Planning Department. Chinatown Area Plan. Available online: https://generalplan.sfplanning.org/Chinatown.htm#CHI_PVN_1 (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Open Street Map. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 29 December 2019).

- Alawadi, K. Place attachment as a motivation for community preservation: The demise of an old, bustling, Dubai community. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 2973–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, H. Conflicting perceptions of neighborhood. In Sustainable Communities: The Potential for Eco-Neighborhoods; Barton, H., Ed.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T.; Bontje, M. Responding to tough times: Policy and planning strategies in shrinking cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotch, H.; Freudenburg, W.; Paulsen, K.E. History repeats itself, but how? City character, urban tradition, and the accomplishment of place. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2000, 65, 791–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROTECT the ELLIS ACT. Available online: http://www.preservetheellisact.org/history/ (accessed on 26 November 2019).

- Jacobs, J. The Death and Life of Great American Cities; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitschrift fur Architektur und Stadtebau ARCHPLUS. Shrinking Cities–Reinventing Urbanism. Available online: http://www.shrinkingcities.com/index.php%3Fid=227&L=1.html (accessed on 9 December 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).