Abstract

This article empirically examines the connection between the board of directors’ characteristics and excesses in remuneration for directors from a sustainability perspective, highlighting the role of information transparency on remuneration control. Using data from 73 listed companies in the period 2007–2012 (the global financial crisis), we find that (1) board size presents a non-linear relationship with excessive total directors’ remuneration during the crisis period; (2) other board characteristics (board independence, duality and directors’ ownership) do not show a significant relationship with excessive directors´ remuneration; and (3) voluntary transparency on directors’ remuneration significantly contributes to controlling excessive total directors’ remuneration, which contributes to the long-term sustainability of the firm. The results of this study provide good reasons to take into account the effect of corporate governance characteristics and transparency on the remuneration excesses committed during the global financial crisis.

1. Introduction

The sustainable perspective of the firm, which is based on the integration of economic, social, and environmental concerns into management decisions and the firm’s aims, increases corporation’s responsibility to their stakeholders. From this perspective, corporate governance is one of the essential mechanisms in balancing all stakeholder interests, thereby improving the ability of the firm to prosper and achieve long-term success. In fact, corporate governance is the set of processes and rules that direct, manage, and control the firm. Mechanisms of corporate governance have been revised by literature to evaluate the level of corporate governance goodness, from agency theory principles to a broader view based on stakeholder perspective. In general terms, the literature on corporate governance demonstrates the awareness of the importance of good corporate governance in achieving corporate performance in the long term, and therefore, future sustainability [1,2].

However, the high remuneration conducted by many boards of directors, particularly during the economic downturn, has triggered a sweeping confidence crisis in all domains. The role of boards of directors as the bodies monitoring and controlling the remuneration of their members is now questioned. Moreover, what is being challenged is if the compensations obtained by directors are renumeration excesses. This challenge has heated the debate regarding the expropriation of wealth from the remaining stakeholders stemming from these remunerations [3,4]. Prior studies have stated that an adequate remuneration for directors leads to a greater effort, thus enhancing corporate performance [4], and studies have called for a connection between earnings management and corporate social performance to achieve long-term sustainability [5]. However, it is still disputed whether the remuneration of certain directors matches their dedication, qualification or degree of responsibility [6,7,8]. Since it is perceived that directors’ remuneration can be excessive with regard to the role they perform and that they are barely related to the interest of other stakeholders, it is necessary to further examine how corporate governance mechanisms may help to mitigate or aggravate potential excesses in remuneration.

According to statements made on the basis of agency theory [9], particularly regarding corporate governance mechanisms, certain features of the board of directors (for instance, a low number of independent members on the board) may lead to excesses in remuneration. Such excesses can be construed by shareholders and the remaining stakeholders as an expropriation of their wealth, thus contributing to a conflict of interest between management and shareholders alongside the remaining stakeholders, on the one hand, as well as between majority and minority shareholders, on the other hand [10,11]. Hence, at least from a theoretical standpoint, the board of directors’ structure is very significant in regard to giving an account of the remuneration paid to board members. Despite the wide empirical evidence [12,13,14,15] about the influence of the board of directors on directors’ compensation, the majority of previous studies have measured compensation as total granted remuneration. This measure is global, and it does not take into account if the remuneration is excessive or not or if the remuneration is related to, for example, the effort made by the directors or the firm performance. In fact, the obtained results in previous studies are mixed and, therefore, not conclusive.

Similarly, the lack of transparency regarding remuneration has been considered a main reason for the failure of corporate governance as a mechanism to control directors’ remuneration. In this sense, the OECD [16] considers both corporate governance and corporate disclosure as inseparable issues for investor protection and for the efficiency of capital markets. Thus, on the one hand, it is generally acceptance that the different mechanisms of corporate governance can protect shareholders from expropriation by managers [17]. On the other hand, the disclosure of information can result in higher firm value and lower asymmetric information [18].

From a theoretical point of view, greater transparency has been advocated for concerning directors’ compensation agreements, based on the argument that the greater the transparency, the more efficient the allocation of remuneration (the optimal contracting approach or contracting hypothesis). In fact, the lack of transparency in the business domain has demonstrated that it provides an opportunity for directors to set remunerations that fail to match their actual work [19] and to take more power to increase their own compensation at the expense of other stakeholders [20]. In this sense, it is demonstrated that if there is a topic that has been based on a large opacity of information, it is the issue of directors’ remuneration [15], despite the importance of this information to both shareholders and stakeholders. On the one hand, the shareholders need adequate information about the level of remuneration and system to control these policies in an effective way [20]. On the other hand, the stakeholders need the information to know if the level of remuneration is adequate, thereby avoiding excessive remuneration [21] that the shareholders could perceive as an expropriation of their wealth. Based on awareness of the importance of transparency, one of the recommendations taken at the international, European and national levels has focused on increasing the information transparency of compensation practices, particularly regarding the detailed compensation policies and individual compensations granted to members of boards of directors. In this sense, could transparency be the tool to avoid the expropriation of wealth to shareholders through excesses in remuneration of directors when corporate governance is weak?

To answer this question, we complement previous studies about the relationship between the characteristics of the board and directors’ remuneration, first, by measuring remuneration with other measures, such as excessive total directors’ remuneration and excessive directors’ remuneration, according to the effort or the activity performed. Second, we have included in the analysis the voluntary disclosure of remuneration, with the objective of the study focused on the effect of this variable on the excessive remuneration granted to the directors, which is an item that has received scarce attention in the previous literature. In fact, according to our understanding, there is no previous research study about the relationship between the voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration and excessive directors’ remuneration. In this sense, and as a novelty with the objective of measuring the impact of the voluntary disclosure of directors´ remuneration, we have built two indexes based on the recommendations of the CUBG [22]: (a) The voluntary disclosure index of pay strategy to directors (PSVD) and (b) the voluntary disclosure index of individual compensation received by directors (ICVD).

We have chosen the Spanish context during the crisis period to carry out this empirical analysis since it is a good example of the excess remuneration granted to directors that was produced by some companies in those years. In fact, although the Spanish economy had to cope with gross domestic product (GDP) decreases between 2008 and 2012 and the level of unemployment rate growth from 8.57% in 2007 to 25.77% in 2012 (and greater in the last decade), the level of directors’ remuneration increased throughout that period. According to a study conducted by Heidrick and Struggles [23] in Europe, Spanish companies paid €108,000 on average to their directors (which is in third position, only behind Switzerland and Germany, and ahead of countries such as Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, and Denmark). However, the results of this work can be extrapolated to other contexts since this problem is not unique to Spain, and it has occurred in many other countries around the world. In addition, this period allows us to study the voluntary disclosure of remuneration granted to directors since such information has subsequently become mandatory. Because we would like to study the effect of the crisis on the remuneration to directors and the role of transparency in the control of such excesses, we chose that period in which to develop the empirical testing.

The results of this study have several theoretical contributions. First, this study goes beyond the directors’ remuneration control frame by analyzing the relationship between corporate governance characteristics, excessive total directors’ remuneration and excessive directors’ remuneration according to their dedication. Our findings emphasize the role of board size in controlling the total level of director remuneration. Second, this research shows that the voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration has been significant in controlling the total level of directors’ remuneration during the global financial crisis. Consequently, new tools are required to control directors’ remuneration, and this work gives some directions in this sense.

This work is structured in five sections. In the first section, we review the scholarly literature on the topic and put forward all the hypotheses to be tested. In the second, we provide the sample and the variables examined herein. The third section includes the application of the relevant statistical techniques. The fourth section provides the analysis of the main results, and finally, the fifth section delivers the main conclusions, limitations, and future lines of research.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Remuneration of Directors: Excesses and Conflicts with Stakeholders

Although the remuneration control of board members has been acknowledged lately in various codes of good governance worldwide, all the efforts made do not seem to have a desirable practical application. International cases such as those of Enron or the American International Group (AIG) or the domestic Bankia case in Spain, among others, have increased the interest in this matter over the last few years. Furthermore, certain corporate governance structures adopted by companies empower the board of directors to ultimately determine their own remuneration, thus leading to a discretion that may undermine the interests of the remaining stakeholders. Thus, in many cases, the scope of discretion of directors to influence their own compensation agreements is too broad [3]. This situation allows the board to allocate an excessive remuneration to themselves that fails to match their actual role, as has occurred in the abovementioned specific cases. Indeed, in some of those cases, the salaries perceived by directors were artificially increased while the companies were undergoing economic and financial troubles that jeopardized their subsistence. Ultimately, the company faces the dilemma of either offering their directors an appropriate remuneration, thereby allowing the company to retain and attract professional directors, or avoiding excessive compensation, which may compromise their independence and the appropriate performance of their duties.

Remuneration excesses can entail a conflict of interests between directors, who are responsible for their own remuneration, and the remaining stakeholders, who can see how their wealth decreases due to this kind of practice. This involves identifying any potential causes that may give rise to the issue, as well as specifying any possible solutions. Scholarly literature has focused on these two aspects lately. However, most of the previous works that have examined whether remuneration occurs in response to the actual performance of directors have measured the remuneration as the total amount granted without taking into account whether the remuneration is excessive or the effort made by the directors. The academic debate on corporate governance and directors’ remuneration has examined certain specificities in depth. Excesses in the remuneration of executive directors have been related to opportunistic behaviors or “managerial self-dealing” [24]. When executive directors gain power with respect to the board of directors, non-executive directors can be reluctant to monitor and discipline the managers. Then, the executive directors can use their power to carry out policies that can harm the interests of the remaining stakeholders, for instance, by implementing a wrong investment policy [25], by an excessive consumption of goods [26] or by adopting remuneration policies that particularly help them [19]. In line with this rationale, boards with too much power are able to obtain income from shareholders and the remaining stakeholders through their own remuneration [4]. In this regard, the results of the study conducted by [27] allowed us to conclude that low-performing companies are more prone to suffer excesses in compensation to management and to board members. Although they construe these results as a sign of cronyism between managers and board members, it is obvious that these remuneration excesses can be due to an expropriation of wealth from the remaining stakeholders, as experience has shown in some of the abovementioned cases.

For executive directors, an excess in the remuneration perceived by non-executive directors has been connected with the possible issues of “capture by the first executive” and “collusion with other executives”, i.e., a lack of independence and control, and thus a loosening in the performance of their duties [28]. In other words, there is a risk that directors perform their duties based on the wishes of the chairman (who often chairs the board too), thus becoming mere attendees to the meetings in exchange for greater compensation.

2.2. Characteristics of the Board of Directors and the Remuneration of Its Members

According to statements made on the basis of agency theory [9], certain features of the board of directors (for instance, a low number of independent members on the board) may lead to excessive directors’ remuneration. Such excesses can be construed by shareholders as an expropriation of their wealth, thus contributing to a conflict of interests between management and shareholders, as well as between majority and minority shareholders [10,11]. In fact, prior studies (theoretical and empirical) have shown that the characteristics of the board of directors have a great impact on the efficiency thereof; therefore, board members can act as true supervisors by controlling managers and representing the interests of shareholders. In light of this connection, prior works have proposed various mechanisms to increase the degree of independence and efficiency of boards of directors [8,29,30,31,32], including (a) splitting the positions of the chairman of the board and the chief executive officer; (b) moderating the size of the board; (c) incorporating independent board members; and (d) fostering the shareholding of directors in the company.

In many companies, the same person holds the positions of chairman of the board and the chief executive officer; this is called the accumulation of power or duality. In these cases, although theoretically one could think that the accumulation of power could “reduce information and coordination costs” (Unified Code of Good Governance, in Spanish Código Unificado de Buen Gobierno, hereinafter CUBG, 2015) [33], works on this topic contend that agency issues will be greater since the control of the board will be negatively affected (the chief executive officer would not be accountable to the chairman of the board, since the same person would hold both positions) [11,33,34,35]. Additionally, the chief executive officer could take advantage of this lack of control to gain favor with directors in exchange for keeping them in their position and/or for paying significant compensation to them [36]. Previous empirical studies have shown that companies with an accumulation of power grant greater remunerations to their board members [7,12,30,37]. As a consequence, we hereby propose that duality will have a positive impact on excessive directors´ remuneration, leading to greater remunerations for directors.

Hypothesis (H1).

Duality is positively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors’ dedication).

Another debated issue regarding the board’s structure relates to its size. There are many opinions in this respect. On the one hand, some favor large boards, considering that they contribute to the diversity of criteria and that they help in dealing with more and better information [38], which would enhance the board’s efficiency [39] and independence [40], thus hoping to prevent excesses in the remuneration received by directors. In contrast, some advocate for small boards, claiming that decision-making processes will be quicker and more efficient and that there will be less coordination issues since there are fewer members [26,41]. Empirically, there is no consensus on the results. In fact, some studies have shown a negative relationship between size and remuneration to directors [8,32], while others have seen a positive relationship [42]. The study by Brick, Palmon, and Wald [7] found no relationship between those two variables; Andrés and Vallelado [42] and Yermack [11] even argue that there is a non-linear relationship between the variables such that for small boards, there will be a negative relationship between boards’ size and efficiency in the exercise of their duties up to a certain limit from which it will then become a positive relationship. According to these results, we cannot clearly define the kind of relationship in terms of hypothesis. Therefore, the following hypotheses have been proposed:

Hypothesis (H2a).

Greater board size is positively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors’ dedication).

Hypothesis (H2b).

Greater board size is negatively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors’ dedication).

Another feature of the board’s structure that has been previously considered significant is the presence of independent board members (not subject to the company’s, the directors’ or the top management’s influence). The purpose of including these directors is to help control the chief executive officer’s power [20], as well as to ensure the board’s independence and efficiency [30]. It is expected that this presence will lead to guaranteeing that all shareholders’ interests are pursued [43], regardless of whether they are majority or minority shareholders. In addition, this kind of director must preserve their reputation within the labor market [30]. Departing from these ideas, one could think of a negative relationship between the number of independent directors and the remunerations paid to directors, but such a situation has not always appeared, according to the empirical studies that have examined this relationship. Hence, researchers have shown this to be negative relationship [8,32,42], whereas others have shown it to be a positive relationship [44]. The foregoing challenges the effectiveness of independent board members regarding the control of directors’ remuneration. Thus, we do not define a specific sense of the relationship between board independence and the possible excessive directors’ remuneration. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3 in the following terms:

Hypothesis (H3a).

Board independence is positively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors’ dedication).

Hypothesis (H3b).

Board independence is negatively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors’ dedication).

Finally, we refer to directors’ shareholding as a corporate governance mechanism that helps to line up their interests with those of shareholders (convergence hypothesis) [9] and the remaining stakeholders. Accordingly, the greater the shareholding interests of the directors, the greater their incentives to control the chief executive officer [44] and the board [45]. Additionally, in these cases, it will not be as necessary to pay high compensations since they already receive a large dividend from the shares they hold [29]. All of this leads to the thought that in those companies where directors have shareholding interests, their remuneration will be lower, as evidenced by certain prior empirical studies [46,47,48]. In this regard, and according to the development of previous works, we posit the following hypothesis to be tested:

Hypothesis (H4).

Directors’ shareholding is negatively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors´ dedication).

2.3. Voluntary Disclosure of Directors’ Remuneration

Generally, information transparency helps reduce issues related to information asymmetries amongst stakeholders [49]; particularly concerning directors’ remuneration, it will allow the disclosure of, among other aspects, directors’ remuneration policies, remuneration items paid to each of them and the ratio between their remuneration and the corporate performance. Put another way, information on remuneration will allow users to assess if the board is efficiently allocating these items [50]. Moreover, the fact that the actual directors provide information on their compensations could be regarded by shareholders and the remaining stakeholders as an act of goodwill through which they would be showing that the remunerations received are not excessive but in line with their work [50]. In fact, from a theoretical standpoint, greater transparency has always been advocated for regarding directors’ remuneration, based on the claim that the greater the transparency, the greater the remuneration allocation process efficiency (which is the optimal contracting approach or the contracting hypothesis).

Nonetheless, such information transparency has not always existed within all companies, and it has not always been true for all aspects of compensation. In fact, the individual compensation paid to directors is the least publicized item by companies, based on the belief that it would affect personal interests (reputation, professional standing, honor, etc.) or even give rise to a salary war due to the increased competition for the best executives [51], which would also trigger a substantial increase in those remunerations. However, the majority opinion amongst scholars notes that the lack of transparency could be used by the board to increase board members’ remunerations at the expense of other stakeholders [20], as well as to hide or conceal such compensation excesses [19]. The said remuneration increases could be construed by shareholders as rent extraction, and more specifically, an extraction of their wealth [4].

Based on the foregoing arguments, information transparency regarding remuneration could deter abusive or excessive directors’ remuneration. Thus, we posit the following hypothesis to be tested:

Hypothesis (H5).

Voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration is negatively associated with excessive directors’ remuneration (greater total level of remuneration or greater remuneration in relation to directors’ dedication).

3. Data and Variables

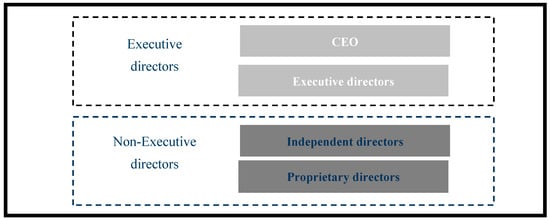

The prevailing corporate governance system in large Spanish companies is the unitary board system, which is characterized by grouping non-executive or outside directors (NED) and/or executive or inside directors on the same board (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Typical board structure in Spain. Source: Merino, Manzaneque and Banegas [12] (p. 395).

Along these lines, with the aim of testing the proposed hypotheses, we have departed from all listed companies on the Spanish Continuous Market for the period 2007–2012. As we would like to capture the effect of the global financial crisis on the firm, we have chosen those firms that were quoting during that period. Therefore, after disregarding those not-listed firms for the selected period, the final study sample is made up of 438 observations (73 firms × 6 years). This sample provides a broad representation of the population in terms of sectors and firm characteristics of the Spanish listed companies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of the population and sample firms according to the industry type.

The following sources have been used to obtain the data: databases of the Spanish Securities and Exchange Commission (Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores, CNMV) and the Annual Corporate Governance Reports, as well as each company’s annual accounts and other sources of information, such as companies’ websites, information contained in the various registries held by the Madrid and/or the Barcelona Stock Markets, etc. The panel data methodology with two-step GMM (Generalized Method of Moments) estimates has been applied [52].

3.1. Dependent Variables

Several proxies of “excessive remuneration pay to directors” have been taken to test the hypotheses as follows:

Excess of total volume of remunerations (ER1): We calculated the difference between the firm’s total remuneration to each member of the board of directors and the average of the sector. The total remuneration of the directors includes the following items: fixed and variable compensation, allowances, items specified in the company’s bylaws, stock options and/or other financial instruments alongside other remuneration items [53,54]. Similarly, certain remuneration items have been removed, such as indemnities, since they could distort the results due to their occasional nature and high volume, thus making the interpretation very difficult. To test remuneration in terms of volume as a dependent variable, the total compensation per director was accounted for.

Excess remuneration according to the effort or the activity performed (ER2): Regarding corporate governance in Spain, the CUBG (2013) [55] includes, among others, the following recommendation: The “compensation paid to outside directors must be as necessary as to remunerate the dedication, qualification and responsibility required by the relevant position. However, it must not be raised as much as to compromise independence.” Spanish legislation does not set limits for the degree of remuneration or requirements concerning the structure thereof. Nevertheless, from the wording of the CUBG (2013) [55], it can be inferred that companies must compensate their directors based on effort and the control duties they perform [6,7,8]. Previous works have used the number of meetings as a proxy for directors’ degree of effort or activity level. The number of meetings has been associated with enhanced corporate governance [56]. From an empirical viewpoint, Boyd [46], Brick, Palmon, and Wald [7] and Andreas, Rapp, and Wolff [8], among others, have provided evidence that remuneration levels are positively correlated to the board’s number of meetings. This work departs from the hypothesis that the remuneration received by directors must be in line with their activity. Thus, a higher compensation per meeting can be a sign of expropriation and excessive director remuneration. In this sense, the variable is calculated as the difference between the firm’s remuneration to each director per number of board meetings and the average of the sector.

3.2. Independent Variables

Independent variables relate, on the one hand, to the characteristics of boards of directors and, on the other, to the voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration.

Within the first group of characteristics of boards, four variables have been used that have been widely used in prior studies [30,44,45,47,48,56,57]: duality, size of the board, independent directors and directors’ shareholding interests (see Table 2). Likewise, the square of the board’s size has been included to record possible non-linear relationships between the latter and the remuneration paid to directors [11,42]. Differently put, it is normally argued that the relationship between the size of the board and its efficiency, among other aspects, in terms of the remuneration of the board members, is a positive relationship up to an optimal point from which the addition of another member does not help to improve its control capacity; in contrast, such an addition leads to coordination, control, and effectiveness issues with regards to decision-making processes.

Table 2.

Definition and typology of variables.

Concerning voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration, two indexes have been used based on the recommendations issued by the Unified Code of Good Governance (CUBG) (2006) [22]: (a) The voluntary disclosure index regarding directors’ remuneration policy (PSVD); and (b) the voluntary disclosure index regarding the individual remuneration received by each director (ICVD). The items contained within each of these indexes are based on the content of recommendations no. 35 and no. 41 of the CUBG [22] and have been taken from Manzaneque, Merino and Banegas [58] (see Appendix A).

3.3. Control Variables

Many previous studies [7,8] have shown a significant relationship between the company’s size and the amount of the compensations granted to directors, which would be based on the fact that larger companies demand more qualified directors to perform their duties and thus those directors will receive a higher remuneration [4].

Corporate performance has also been shown to be a variable that could influence the remuneration level of directors. Therefore, we consider that the greater the financial return, the greater the remuneration to be paid to directors, as evidenced by previous works [8,29,59,60].

In addition to the foregoing, in this case, the industry to which each company in the sample belongs has been included as a control variable, considering that prior studies have also shown that industry is a significant aspect regarding directors’ remuneration. In fact, Schiehll and Bellavance [61] explain that external mechanisms of corporate control, such as the capital market, the human capital market and the market for goods and services, are specific for each industry, and their impact will therefore depend on the industry to which each company belongs.

Finally, growth and risk are included as control variables. Previous literature indicates that firm growth is related to the level of remuneration pay to directors. In fact, earlier studies argue that, in contexts with growth possibilities, the directors prefer to take advantage of these opportunities instead of obtaining high remuneration. Therefore, a negative relationship between both variables is expected [62]. In addition, riskier firms are related to greater remuneration to directors because they are compensated by such risk. In this sense, following Wahad and Rahman [63], we take the leverage variable as a proxy of the level of a firm’s risk.

4. Methodology

With the aim of testing the posited hypotheses, various models based on the linear regression of panel data have been developed and applied to numerous phenomena observed in various periods for the same companies [64]. Following this methodology, a sample of 438 observations (73 companies × 6 years) has been used, being a linear and very balanced panel sample. In line with the foregoing, different variants of the model have been estimated as follows (We assume that parameters are homogeneous, meaning that αit = α for all i,t and βit = β for all i,t.):

where yit is the dependent variable (measured as ER1 and ER2; for more details, see Table 2), and represents the control variables. Following the practices implemented in previous studies [29,45,65], a logarithmic transformation of the dependent variable has been performed to reduce heteroscedasticity. The remaining independent variables are defined in Table 2. With regard to the persistence in time of the total remuneration received by directors, the delayed dependent variable (yit−1) has been included in the relevant models [66,67].

5. Results and Discussion

The descriptive statistics of the variables used in the study, alongside their correlations, are shown in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Descriptive summary statistics on panel data variables.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix.

The results of the linear regression of the panel data appear in Table 5. Panel A of the table contains Models 1 (using the PSVD variable) and 2 (using the ICVD variable), where the dependent variable is excessive total directors’ remuneration (ER1). In both models, similar results are obtained with respect to all the independent variables used. Regarding the variables of the board of directors’ characteristics, directors’ shareholding (OWNERDIRECT) shows a positive sign in both models but is not statistically significant in either. The duality variable (CEODUALITY) shows a contradictory sign (positive in Model 1 and negative in Model 2), although in neither case are the results significant. The percentage of independent directors on the board (INDEPEND) shows a negative relationship with the dependent variable, although there is no significant relationship between the variables. Finally, the size of the board (BRDSIZE) shows a significant and positive relationship, and the squared of the size of board (BRDSIZE2) shows a significant and negative relationship. Therefore, a non-linear relationship between board size and excessive total director remuneration is demonstrated. In sum, these results lead us to reject Hypotheses 1, 2a, 2b, 3a, 3b and 4. For variables representing the voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration, both the PSVD and ICVD variables show a negative and significant relationship with the dependent variable in Models 1 and 2. Therefore, we can conclude that the lower the level of information transparency is (both regarding remuneration policies and individual remuneration), the greater the remuneration per director is, thus confirming the theoretical stance that the more transparent the remuneration allocation process is, the more efficient it will be (optimal contracting approach). This result allows us to accept Hypothesis 5 regarding excessive total remuneration to directors. Finally, concerning the control variables, both performance (ROA) and company size (CRPSIZE) show positive and significant results. Thus, as corporate performance and company size increase, higher remuneration per director is granted. However, neither the growth of the firm (FIRM GROWTH) or the risk (RISK) show a significant relationship with the dependent variable.

Table 5.

Estimation: GMM (Generalized Method of Moments) system in two steps.

Panel B of Table 5 contains Models 3 (using the PSVD variable) and 4 (using the ICVD variable), where the dependent variable is excessive directors’ remuneration according to the effort or the activity performed (ER2). Regarding the characteristics of the board of directors, the duality (CEODUALITY) and directors’ shareholding (OWNERDIRECT) variables do not show significant relationships. Thus, we cannot accept Hypotheses 1 or 4. In relation to the size of the board (BRDSIZE), similar to the previous models, this variable shows a significant and positive relationship, and the square of the board of size (BRDSIZE2) shows a significant and negative relationship. Therefore, a non-linear relationship is again demonstrated, leading us to reject Hypotheses 2a and 2b. Finally, the board independence variable (INDEPEND) shows a negative and significant relationship in Model 4 (using the ICVD variable), while that in Model 3 (using the PSVD variable) is negative but not significant. These results lead us to reject Hypothesis 3a and partially accept Hypothesis 3b. For those variables representing the voluntary disclosure of directors’ remunerations, neither of the two variables used (PSVD and ICVD) show significant relationships with the dependent variable, although the sign in both variables is negative, which indicates that remunerations become more moderate as transparency increases. With regard to these results, we cannot accept Hypothesis 5 in this case. Concerning the control variables, as in the previous models, both corporate performance (ROA) and the company’s size (CRPSIZE) show a positive and significant relationship with the dependent variable. In relation to the growth of the firm (FIRM GROWTH), this variable does not show a significant relationship with the dependent variable, although the risk variable (RISK) shows a positive and significant relationship in Model 4 (using the ICVD variable).

In summary, the results reveal that corporate governance mechanisms were not efficient in the control of excess remuneration to directors in the Spanish market during the 2008–2012 financial crisis period. In contrast, the levels of voluntary transparency for directors’ remunerations (both PSVD and ICVD) are significant in explaining excesses in total remuneration per director. In other words, a greater level of transparency reduces the distance between the remuneration of each director and the mean of the sector.

Because our study focuses on the crisis period, we cannot preclude similar results outside the financial crisis because we have not tested other periods.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses concerns expressed by previous literature, regulators, minority shareholders, and society over the excessive directors’ compensations regarding the role they perform to protect the sustainability of the company in the long term. In this sense, we investigate the link between corporate governance mechanisms, the voluntary disclosure of directors´ remuneration and excessive director remuneration. If corporate governance characteristics and transparency provide sufficient tools to achieve an adequate director’s remuneration, firms with the separation of roles between the chair and the chief executive officer, an appropriate total number of members and independent members in the board, more shares owned by the directors and more voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration should contribute to controlling excesses in directors’ remuneration (i.e., total remuneration and remuneration according to the effort or activity performed).

The findings show that during the financial crisis in Spain (2007–2012 period), the effect of corporate governance characteristics on excessive directors’ compensation was very limited. The obtained results in the different models lead us to reject Hypotheses 1, 3a, 3b and 4. Only the board size shows a non-linear relationship with the dependent variable. However, we reject Hypotheses 2a and 2b because a positive and negative linear relationship was hypothesized. In the context of this study, the existence of a non-linear relationship between board size and excessive director remuneration shows that for small boards, there will be a positive relationship between board size and excessive director remuneration up to a limit, at which point it will become a negative relationship. Therefore, greater board size is more efficient in controlling the excesses of remunerations.

Finally, we find that the voluntary disclosure of compensation policies and individual remuneration levels are significant mechanisms for controlling excessive total directors’ remuneration, while voluntary disclosure is not significant for controlling excessive directors’ remuneration with respect to their effort or dedication. These results lead us to partially accept Hypothesis 5.

In general terms, the results of this study confirm that corporate governance mechanisms were not efficient in controlling remuneration excesses in the period of financial crisis that occurred between 2008 and 2012 in Spain. However, voluntary information transparency systems have been significant in controlling such excesses. Thus, firms with higher levels of transparency, both about pay strategy and individual remuneration to directors, show lower levels of excess remuneration per director compared to the sector average. In contrast, we cannot assert that the level of transparency allows the control of remuneration excesses in terms of dedication. In fact, previous studies have asserted that remuneration systems in Spain are not properly linked with the measures of level of work assumed by the directors. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that corporate governance and transparency do not work properly in the control of excessive directors’ remuneration, despite the fact that only they can control the excesses in the total remunerations of directors.

Therefore, this study makes an important contribution to the literature about the voluntary disclosure of directors’ remuneration. In fact, theoretical developments in the compensation transparency theory suggest that rent extraction is negatively associated with the transparency of compensation [3], which is a result that has not always been demonstrated at the empirical level; yet this work demonstrates that result. However, when compensation is measured in terms of dedication, it appears not to have the desirable control effect on excessive remuneration. Therefore, the quality of directors’ remuneration disclosure should be analyzed. It may be a good solution to include the same information in the directors’ compensation reports about the relationship between remuneration and dedication.

The results of this study provide good reasons to take into account the effect of corporate governance characteristics and voluntary disclosure on the excessive remuneration granted to directors during the global financial crisis in Spanish companies. Thus, investors and regulators should be aware of the importance of this issue and take into account the results of this study to implement additional corporate governance reforms to avoid the expropriation of wealth to shareholders and other stakeholders through excessive directors’ remunerations that could jeopardize the sustainability of the company. As we have concluded above, corporate governance and transparency have a limited impact on controlling excessive directors’ remuneration regarding their dedication. It could be interesting in future research to investigate how firms could improve their corporate governance and remuneration reports to control excessive directors’ remuneration.

We acknowledge that this study has some limitations. First, due to the focus of our study, we have overlooked some other variables such as board members’ training and professional experience and the board´s diversity, among others. Second, this study focuses on Spanish listed companies over the period of the financial crisis (2007–2012). Future studies could extend the studied countries with the objective of obtaining results that are more robust since the crisis was global. In addition, due to the aim of the study, we cannot preclude similar results outside the financial crisis. Therefore, additional studies could extend the analysis to periods of expansion to test similarities or differences in the behavior of directors’ remuneration control measures. Finally, board remuneration could be disaggregated according to the type of director in future studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M., M.M.-L. and J.S.-A.; methodology, E.M. and M.M.-L.; software, M.M.-L.; formal analysis, E.M., M.M.-L. and J.S.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M., M.M.-L. and J.S.-A., writing—review and editing, E.M. and M.M.-L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by “Catedra Responsabilidad Social Corporativa” Banco Santander-Castilla-La Mancha University.

Acknowledgments

We are also grateful for the feedback from conference participants at the 2016 XXIV European Business Ethics Network Congress in Segovia, Spain, the 2013 EAA Annual Congress in Paris, France, and the 2011 6th Conference on Performance Measurement and Management Control in Niza, France. Any errors of fact or interpretation remain solely our responsibility. This is part of the research developed by the research group Sistemas de Información Externa e Interna de las Organizaciones: Información Corporativa y Para la Gestión (GISEIO), funded by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor for their observations and help during the revision process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Voluntary disclosure of directors’ compensation items list. Manzaneque, Merino and Banegas [58].

Table A1.

Voluntary disclosure of directors’ compensation items list. Manzaneque, Merino and Banegas [58].

| PSVD–VOLUNTARY DISCLOSURE INDEX OF PAY STRATEGY TO DIRECTORS (Recommendation 35, CUBG (2006)) | |

| FIXED COMPONENTS | |

| a.1. | Amount of the fixed components. |

| a.2. | Itemized information on board and board committee attendance fees. |

| a.3. | Estimation of the fixed annual payment. |

| VARIABLE COMPONENTS | |

| b.1. | Types of directors they apply to. |

| b.2. | Relative weight of variable to fixed compensation items. |

| b.3. | Performance evaluation criteria used to calculate entitlement to the award of share or share options or any performance-related compensation. |

| b.4. | The main parameters and grounds for any system of annual bonuses or other non-cash benefits. |

| b.5. | Estimation of the sum total of variable payments arising from the compensation policy proposed, as a function of degree of compliance with pre-set targets or benchmarks. |

| PENSION SYSTEMS | |

| c.1. | Main characteristics of pension systems. |

| c.2. | Estimation of their amount or annual equivalent cost. |

| CONTRACTS CONDITIONS | |

| d.1. | Contracts conditions for executive directors exercising senior management functions. |

| ICVD–VOLUNTARY DISCLOSURE INDEX OF INDIVIDUAL COMPENSATION RECEIVED BY DIRECTORS (Recommendation 41, CUBG (2006)) | |

| COMPENSATION | |

| e.1. | Participation and attendance fees and other fixed director payments. |

| e.2. | Additional compensation for acting as chairman or member of a board committee. |

| e.3. | Any payments made under profit-sharing or bonus schemes, and the reason for their accrual. |

| e.4. | Contributions on the director’s behalf to defined-contribution pension plans, or any increase in the director’s vested rights in the case of contributions to defines-benefit schemes. |

| e.5. | Any severance packages agreed or paid. |

| e.6. | Any compensation they receive as directors of other firms in the group. |

| e.7. | The compensation executive directors receive in respect of their senior management posts. |

| e.8. | Any kind of compensation other than those listed above. |

| SHARE, SHARE OPTIONS OR OTHER SHARE-BASED INSTRUMENTS | |

| f.1. | Number of shares or options awarded in the year and the terms set for their execution |

| f.2. | Number of options exercised in the year specifying the number of shares involved and the exercise price. |

| f.3. | Number of options outstanding at the annual close specifying their price, date and other exercise conditions. |

| f.4. | Any change in the year in the exercise terms of previously awarded options. |

| RELATION BETWEEN COMPENSATION AND MEASURE OF RESULTS | |

| g.1. | Relation in the year between the compensation obtained by executive directors and the firm’s profits, or some other measure of enterprise results. |

Following the path of previous studies, we built an index that assigns the same importance to each item considered [68,69]. As such, the disclosure index for firm “i” to year t (i = 1 to 73) is as follows:

where

represents the voluntary disclosure of the pay strategy to directors or that of the individual compensation received by directors for business i in period t (when the dummy variables that represent disclosure take value 1), and represents the total points that could get the business to report on all aspects recommended by the CUBG (2006) [22] and that apply to it.

References

- Salvioni, D.; Gennari, F.; Bosetti, L. Sustainability and Convergence: The Future of Corproate Governance Systems? Sustainability 2018, 8, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability: An investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Manag. Decis. 2008, 46, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebchuk, L.A.; Fried, J. Pay without Performance; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Duffhues, P.; Kabir, R. Is the pay-performance relationship always positive? Evidence from the Netherlands. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2008, 18, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Thibodeau, C. CSR—Contingent Executive Compensation Incentive and Earnings Management. Sutainability 2019, 11, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, P.; Fay, C. Outside director compensation and firm performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. 1994, 33, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, I.E.; Palmon, O.; Wald, J.K. CEO compensation, Director Compensation and Firm Performance. J. Corp. Financ. 2006, 3, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreas, J.M.; Rapp, M.S.; Wolff, M. Determinants of Director Compensation in Two-Tier Systems: Evidence from German Panel Data. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2012, 6, 33–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.; Meckling, W. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Cost and Ownership Structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermalin, B.; Weisbach, M.S. The effect of board composition and direct incentives on corporate performance. Financ. Manag. 1991, 20, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermack, D. Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. J. Financ. Econ. 1996, 40, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, E.; Manzaneque, M.; Banegas, R. Control of directors’ compensation in Spanish companies: Corporate governance and firm performance. Stud. Manag. Financ. Account. 2012, 25, 391–425. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, G.; Lucas, M.E. El Nivel Retributivo de Los Altos Directivos de Las Empresas Cotizadas Españolas: Influencia del Tamaño Y Composición del Consejo de Administración. Boletín Económico del ICE 2008, 2938, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Core, J.E.; Holthausen, R.W.; Larcker, D.F. Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. J. Financ. Econ. 1999, 51, 269–305. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini, G.; Moloney, N. Executive remuneration and corporate governance in the EU: Convergence, divergence and reform perspectives. Eur. Co. Financ. Law Rev. 2005, 1, 251–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Principles of Corporate Governance. 2009. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=C/MIN(99)6&docLanguage=En (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Mitton, T. A cross-firm analysis of the impact of corporate governance on the East Asian financial crisis. J. Financ. Econ. 2002, 64, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtaruddin, M.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.; Yao, L. Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure in corporate annual reports of Malaysian listed firms. J. Appl. Manag. Account. Res. 2009, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bebchuk, I.; Fried, J.; Walker, D. Managerial power and rent extraction in the design of executive compensation. Univ. Chic. Law Rev. 2002, 69, 751–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyta, P. Compensation transparency and managerial opportunism: A study of supplemental retirement plans. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzoni, S. Disclosure of executive remuneration in listed public utility companies. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2009, 6, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (Spanish Securities Markets Commission or CNMV). Unified Good Governance Code; Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (Spanish Securities Markets Commission or CNMV): Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heidrick & Struggles. Boards in turbulent time. In Corporate Governance Report; Heidrick & Struggles International Inc.: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook, D. Out of the Crisis. Rethinking our Financial Markets; Paradigm Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, D.J.; Denis, D.K.; Sarin, A. Agency problems, equity ownership, and corporate diversification. J. Financ. 1996, 52, 135–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C. The modern industrial revolution, exit, and the failure of internal control systems. J. Financ. 1993, 48, 831–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, I.; Palmon, O.; Wald, J. CEO Compensation, Director Compensation, and Firm Performance: Evidence of Cronyism; Working Paper; Rutgers University: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Paz-Ares, C. Executive Remuneration: An Enigma. Revista Para el Análisis del Derecho 2008, 1, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Firth, M. Ownerchip, corporate governance and top management pay in Hong Kong. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2005, 13, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conyon, M.J.; He, L. Executive Compensation and CEO Equity Incentives in China’s Listed Firms. 2008. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1261911 (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Fahlenbrach, R. Shareholder rights, boards, and CEO compensation. Rev. Financ. 2009, 13, 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, H.E.; Wiggins, R.A. Who is in whose pocket? Director compensation, board independence, and barriers to effective monitoring. J. Financ. Econ. 2004, 73, 497–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (Spanish Securities Markets Commission or CNMV). Good Governance Code of Listed Companies; Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (Spanish Securities Markets Commission or CNMV): Madrid, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, F.A.; Leung, S. Board leadership, outside directors’ expertise and voluntary corporate disclosures. J. Account. Public Policy 2004, 23, 351–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morck, R.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Management ownership and market valuation: An empirical analysis. J. Financ. Econ. 1988, 20, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, G.S. Why CEO compensation is so high. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1991, 34, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saap, S.G. The impact of corporate governance on executive compensation. Eur. Financ. Manag. 2007, 14, 710–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehn, K.; Patro, S.; Zhao, M. Determinants of the Size and Structure of Corporate Boards: 1935–2000; Unpublished working paper; University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, D.A.N.R.; Daily, C.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Ellstrand, A.E. Number of directors and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Acad. Manag. J. 1999, 42, 674–687. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.A.; Zahra, S.A. Board compensation from a strategic contingency perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 1992, 29, 411–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipton, M.; Lorsch, J.W. A modest proposal for improved corporate governance. Bus. Lawyer 1992, 48, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Andrés, P.; Vallelado, E. Corporate governance in banking: The role of board of directors. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2570–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysinger, B.; Bautler, H. Corporate governance and the board of directors performance effects of changes in board composition. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1985, 1, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Shivdasani, A.; Yermack, D. CEO involvement in the selection of new board member: An empirical analysis. J. Financ. 1999, 54, 1829–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.K. Board control and CEO compensation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, B.K. Determinants of US Outside director compensation. Corp. Gov. 1996, 4, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, S.; Hwang, L.S.; Klein, A.; Lilien, S. Compensation of Outside Directors: An Empirical Analysis of Economic Determinants; Working Paper; NYU Working Paper No. APRIL KLEIN-4: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro, J.; Veliyath, R.; Eramus, E.J. An empirical investigation of the determinants of outside director compensation. Corp. Gov. 2000, 8, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, P.; Palepu, K. Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. J. Account. Econ. 2001, 31, 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslu, V. Executive directors, pay disclosures, and incentive compensation in large European companies. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2010, 25, 569–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, P.L.; Zhou, X. Does Executive Compensation Disclosure after Pay at the Expense of Incentives. 2006. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=910865 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.910865 (accessed on 23 November 2019).

- Arellano, M.; Bond, S. Some tests of specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1991, 58, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Long, C. Executive Compensation, Firm Performance, and Ownership Structure: An Empirical Study of Listed Firms in China; Working Paper; Colgate University: Madison County, NY, USA, 2004; Available online: http://www.wesleyan.edu/econ/ChinaStockMarket.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2019).

- Haid, A.; Yurtoglu, B.B. Ownership Structure and Executive Compensation in Germany. 2006. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=948926 (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (Spanish Securities Markets Commission or CNMV). Unified Good Governance Code; Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores (Spanish Securities Markets Commission or CNMV): Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, A.; Peñalva, F. Corporate governance and the weighting of performance measures in CEO compensation. IESE Research Papers No. 556. Rev. Account. Stud. 2006, 11, 463–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.W.; Daniel, N.; Naveen, L. Boards: Does one size fit all? J. Manag. 2008, 27, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzaneque, M.; Merino, E.; Banegas, R. The Role of Transparency and Voluntary Disclosure on the Control of Directors’ Compensation. In Performance Measurement and Management Control: Behavioral Implications and Human Actions; Davila, A., Epstein, M.J., Manzoni, J.F., Eds.; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2014; Volume 28, pp. 257–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y. Corporate Governance, Leadership structure and CEO compensation: Evidence from Taiwan. Corp. Gov. 2005, 13, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrondo, R.; Fernández, C.; Fernández, E. Influence of the corporate governance structure on the remuneration of directors in the Spanish market. ICE 2008, 844, 187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Schiehll, E.; Bellavance, F. Board of Directors, CEO ownership and the use of non-financial performance measures in the CEO bonus plan. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosh, A. The Remuneration of Chief Executives in the United Kingdom. Econ. J. 1975, 85, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswadi Abdul Wahab, E.; Abdul Rahman, R. Institutional Investors and Director Remuneration: Do Political Connections Matter? Adv. Financ. Econ. 2009, 13, 42. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1949792 (accessed on 14 November 2019).

- Hsiao, C.; Lightwood, J. Análisis de especificación para datos panel. Cuadernos Económicos del ICE 1994, 56, 6–27. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.; Hambrick, D.C. Chief executive compensation: A study of the intersection of markets and political processes. Strateg. Manag. J. 1989, 10, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilling, M. The link between CEO compensation and firm performance: Does simultaneity matter? Atl. Econ. J. 2006, 34, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canarella, G.; Nouray, M. Executive compensation and firm performance: Adjustment dynamics, non-linearity and asymmetry. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2008, 29, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camfferman, K.; Cooke, T. An analysis of disclosure in the annual reports of U.K. and Dutch companies. J. Int. Account. Res. 2002, 1, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inchausti, B. The influence of company characteristics and accounting regulation on information disclosure by Spanish firms. Eur. Account. Rev. 1997, 6, 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).